8

Living without a Life-View

He says goodbye to Rasmus Nielsen on the corner of Rosenborggade and Tornebuskegade and goes inside, out of the blazing August sunshine, up the stairs to his cool, shaded rooms. In this part of town the sour stench from the tanneries along Rosenborggade overpowers the other smells of the city wafting on the breeze and rising from the open gutters – rotting fish, old meat, seaweed, sewage. The reek from the tanner’s yard owned by his landlord, Mr Gram, has become unbearable in the hot weather, and his servants are instructed to close the blackened windows before he returns home from his walks. He is exhausted, but agitated; he reaches instinctively for his pen, and paces back and forth across the room. For the last few weeks, since ‘The Crisis and a Crisis in the Life of an Actress’ appeared in The Fatherland, he has agonized about it. Is this ‘little aesthetic article’ a fitting finale for his literary production? How will it be interpreted – or misinterpreted? Over this summer of 1848 he has filled pages of his journal answering his own doubts over whether he should have published it at all. Consumed by anxiety, and convinced he will die soon, he worries that this article will distort his entire authorship.

He does not want to be thought frivolous, or to lessen the impact of his recent religious works – but nor does he want people to think he started out as a daring aesthete, and then became a religious writer simply because he grew older. This happened to many of the early Romantics, who after their youthful pantheist rebellions returned to Christian orthodoxy in middle age – Henrik Steffens became a conservative Lutheran, and Friedrich von Schlegel converted to Catholicism – and of course Kierkegaard does not want to be regarded as a Romantic cliché. No, even the scandalous Either/Or aimed to deepen its reader’s relationship to God; his aesthetic interests and his religious earnestness have always gone together; this late journalistic piece about Madame Heiberg is proof of that.

But will people see it this way? How painful it is to let himself be seen, even obliquely – to pour his energies into communicating this struggle to be human, these questions that he himself lives so deeply – and then to be misunderstood! When these anxieties about his authorship assail him, he tries to console himself with the thought of Rasmus Nielsen’s friendship and loyalty. He never used to think much of Nielsen, a philosophy professor at the University of Copenhagen – indeed, he has often sneered at his mediocrity – but in recent months they have grown closer, taking weekly walks together, Nielsen full of appreciation for his work and eager to learn more about his philosophical views. Kierkegaard has begun to hope that after he dies Nielsen will defend his reputation and secure his literary legacy. This raises fresh uncertainties, though: does Nielsen understand his work sufficiently, and can he really be relied on?

But what is the worst thing about this is that I have managed to get the matter so muddled in reflection that I scarcely know what I am doing. And therefore, even if there had been no other reason for doing so, I would have to act. Nothing exhausts me so terribly as negative decisions: to have been ready to do something, that is, to have found it entirely right, desirable, etc., and then suddenly a great many reflections drift together in a pile in which I could practically perish. It can never be right that something which in itself is insignificant could suddenly actually come to possess a dreadful reality. It is a sign that reflection has become sick. When this happens, action must be taken in order to preserve life. Then indolence will continue letting one imagine that the negative path was after all the best – but that is sheer lies. The only right thing to do is to take refuge in God – and act.

Somehow, amid all his anxiety, charged with caffeine, nicotine and thoughts of mortality – and immortality – he glimpses how these obsessive ruminations about his authorship are driven by egotism and conceit. He cares about the world’s opinion much more than he thinks he should, and (because of his pride, again) more than he wants to admit. Not for the first time, he sees that he suffers because he lacks faith: ‘it is reflection that wants to make me extraordinary, instead of placing my confidence in God and being the person I am.’ Nevertheless this habit of reflection carries him away again and again.

And when did he become ‘the person I am’? This person is inseparable from his authorship: the years before he began to write seem, now, the preparation for his literary life. Yet his authorship has had several false starts as well as false endings. Indeed his days, like some of his books, have been distended by the difficulty of making a start and the difficulty of coming to a stop.

In the mid-1830s his journalistic debut in Copenhagen’s Flying Post – the flippant dismissal of female emancipation posing as ‘Another Defence of Woman’s Great Abilities’ – was followed by three more articles in Heiberg’s journal. These pieces criticized the liberal press, a topic which allowed him to display his polemical wit against two other ambitious young writers, Orla Lehmann and Johannes Hage, who were pushing the liberal agenda. These articles were so clever and eloquent – and so close to Heiberg’s style – that readers assumed Heiberg himself had written them: Kierkegaard was delighted to hear from Emil Boesen that Poul Møller thought them the best things Heiberg had written for a while. After this success, he spent several months planning his first major work, the essay on Faust, only to be beaten to it by Martensen.

Beginning again was difficult. After sulking through the summer of 1837, he moved out of Nytorv that September and rented an apartment a few streets away, on Løvstræde. His new home was at the corner of the square where Martensen lived: from his windows Kierkegaard had a clear view of his rival’s house. His father gave him a generous allowance, and paid off the large debts he had accumulated from buying books, writing paper, clothes, shoes and tobacco, going to the theatre, and frequenting coffee shops and restaurants. In an effort to gain a little independence, he returned to his old school to teach Latin during that autumn term. Soon he was philosophizing about the grammar he had to explain to the boys at the School of Civic Virtue: ‘Modern philosophy is purely subjunctive,’ he wrote in his journal in September; by October, he was finding the same fault in himself – ‘Unfortunately my life is far too subjunctive; would to God I had some indicative power!’

After seven years as a student he felt trapped in a bubble of possibility, floating above the world, unable to enter into it. Academic study had taught him to see his own life as a symptom of a declining age, yet he still did not know how to step out into the world and make something happen. He was overflowing with ideas, but they were diverse, scattered, sketchy. Now that Faust had to be abandoned, he was casting about for a new project. One idea was to write ‘a history of the human soul’, which would follow ‘the development of human nature’ by examining what people of different ages laughed at. A week later he thought about writing a dissertation on ancient Roman satire. Another day, he contemplated ‘a novella in which the main character is a man who has acquired a pair of spectacles, one lens of which reduces images as powerfully as an oxy-gas microscope, and the other magnifies on the same scale, so that he apprehends everything very relativistically’. How often he, Kierkegaard, has been like this man, and turned his distorted gaze upon himself. Meanwhile the nights drew in, the season turned: ‘Why I so much prefer autumn to spring is that in the autumn one looks at heaven – in the spring at the earth.’

The following spring, 1838, he moved back home to Nytorv. In April he recorded Poul Møller’s death in his journal, and resolved to pull himself together: ‘Again such a long time has passed in which I have been unable to collect myself for the least thing – I must now make another little shot of it.’ He started writing a review of Hans Christian Andersen’s new novel Only a Fiddler, the story of a gifted violinist prevented by circumstances from realizing his musical genius in the world. This review gave him an opportunity to develop some of the philosophical ideas he had been discussing with Møller; he hoped it would be published, like Martensen’s essay on Faust, in Heiberg’s journal Perseus. But when Heiberg read it he disliked the heavy, convoluted prose. By August a revised version of the review was nearly finished, but that month the second – and, as it turned out, final – volume of Perseus appeared without it.

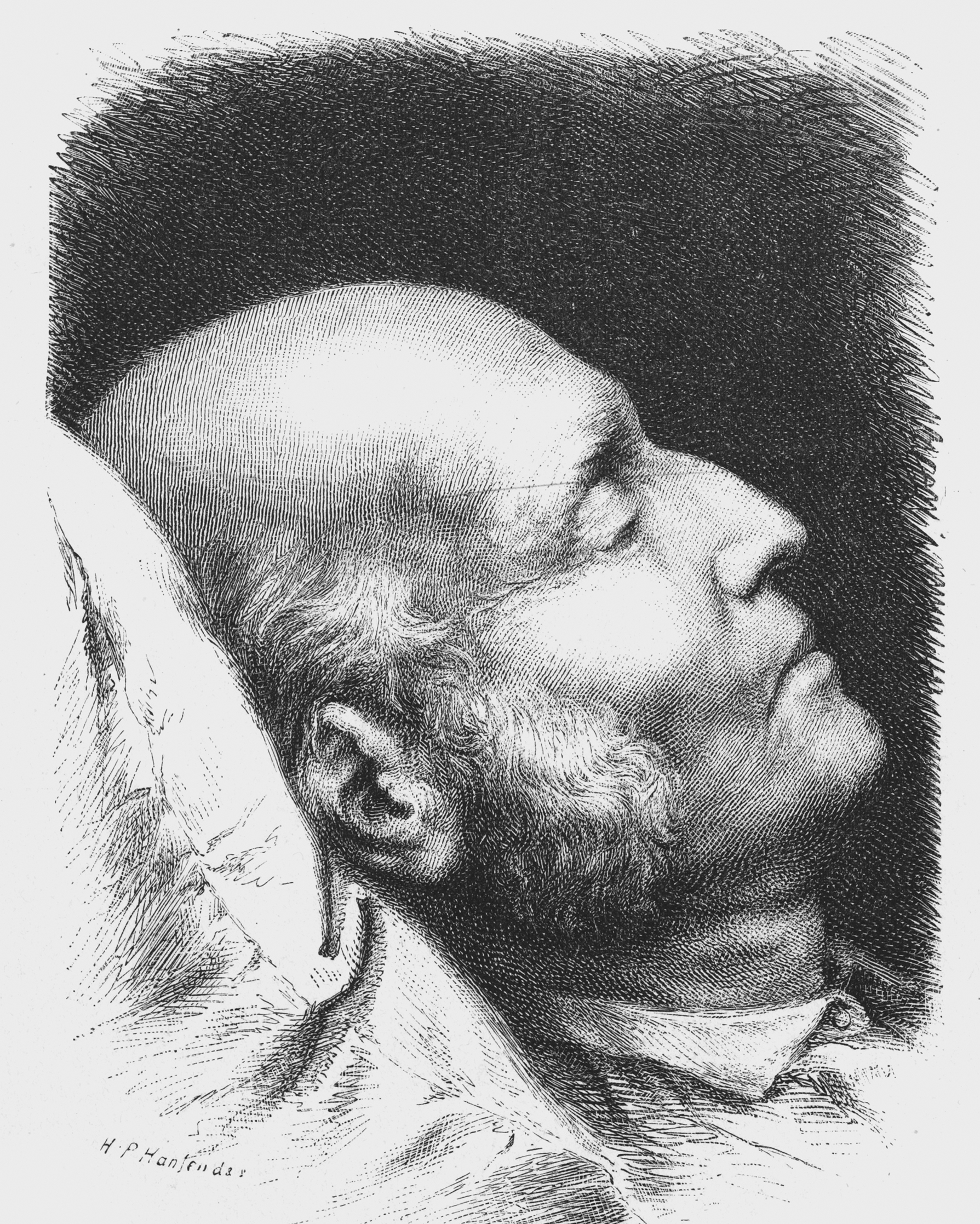

Poul Martin Møller at his death

On 8 August 1838 Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard died. Three days later Kierkegaard opened his journal again, and marked a page with a small black cross:

†

My father died on Wednesday, the 8th, at 2:00 a.m. I did so earnestly desire that he should live a few years more, and I regard his death as the last sacrifice his love made for me, because he has not died from me but died for me, so that something might still come of me. Most precious of all that I have inherited from him is his memory, his transfigured image, transfigured not by my poetic imagination (it has no need of that), but by many little individual traits I am now learning about, and this I will try to keep most secret from the world. For at this moment I feel there is only one person (E. Boesen) with whom I can really talk about him. He was a ‘good and faithful friend’.

Emil Boesen, his confidant since childhood, might have understood why Kierkegaard saw his father as Christ-like: ‘a faithful friend’ – as the old pietist hymns sung of Jesus – whose death was sacrificial, and whose memory was transfigured. Among his friends, only Emil knew something of his deepest roots, had visited his family home as a boy, shared memories of the Moravian meetings on Stormgade. Emil understood what it meant to step from that earlier life into a new world of lectures, novels and newspapers; of philosophy, art and cultural criticism. Kierkegaard’s brother Peter Christian knew about all this too, of course, but he preferred not to open his soul to him.

He soon returned to his essay on Hans Christian Andersen’s new novel, and in September 1838 he published it as a short book entitled From the Papers of One Still Living. If he felt emboldened to put his work out into the world after the deaths of his philosophical mentor and his father, publication was still, to borrow Professor Sibbern’s phrase, an ‘inwardly complicated’ matter. Kierkegaard’s deep habit of reflection, which germinated in the inner conflict and duplicity of his childhood and was nurtured during his long student years, made him feel ‘always, always outside himself’ – and now that he had written something substantial, he could not be at one with it. ‘One Still Living’ was a kind of pseudonym, denoting a ‘friend’ and ‘alter ego ’, and the title page indicated that he, S. Kierkegaard, had published the book against this author’s will.

He wrote a preface, signed ‘The Publisher’, which expressed his ambivalent relationship to himself as a writer:

Our opinions nearly always differ and we are perpetually in conflict with one another, although under it we are united by the deepest, most sacred, indissoluble ties. Yes, although often diverging in magnetic repulsion, we are still, in the strongest sense of the word, inseparable, even though our mutual friends have seldom, perhaps never, seen us together, albeit that someone or other may at times have been surprised that just as he has left one of us, he has, almost instantaneously, met the other. We are, therefore, so far from being able to rejoice as friends in the unity for which poets and orators in their repeated immortalizations have only a single expression – that it was as if one soul resided in two bodies – that with respect to us it must rather seem as if two souls resided in one body.

Like all human beings, Kierkegaard continued, the author of this review had a soul that passed through myriad phases, turning on its axis like the earth moving through the signs of the zodiac. The turbulent process of writing followed this cycle: when his soul entered ‘the sign of hope and longing’ he withdrew into himself and then emerged, ‘half-ashamed’, to struggle and strive with one of the fleeting ideas he had discovered in his ‘inner sanctum’.

After many rotations of his soul – through sadness, anxiety, consternation, as well as ‘moments of blessing’ – the essay was finished, and then the Publisher (S. Kierkegaard), ‘the medium through which he telegraphs with the world’, arranged to have it printed. But the author, who suffered ‘to a rather high degree from a sense of unfulfilment in the world’, was recalcitrant:

You know very well, said he, that I consider writing books to be the most ridiculous thing a person can do. One surrenders oneself entirely to the power of fate and circumstance, and how can one escape all the prejudices people bring with them to the reading of a book, which work no less disturbingly than the preconceived ideas most bring with them when they make someone’s acquaintance, with the result that very few people really know what others look like? What hope can one entertain that one will fall into the hands of readers wholly ex improviso [without expectations]? Besides, I feel tied by the fixed form the essay has finally acquired and, in order to feel free again, will take it back into the womb once more, let it once again sink into the twilight from whence it came.

And anyway, the author added, S. Kierkegaard wished to publish his review simply because he was blinded by vanity. ‘Stuff and nonsense,’ the Publisher retorted: ‘I will not have another word! The essay is in my power; I have the command.’

Having brought out the pathos as well as the comedy of his inner conflict, Kierkegaard’s review enumerated weaknesses in the style, plot and characterization of Andersen’s Only a Fiddler. He particularly disliked its description of genius – a subject close to his own heart – as ‘an egg that needs warmth for the fertilization of good fortune … like the pearl in the sea it must await the diver who brings it up to the light, or cling fast to mussels and oysters, the high fellowship of patrons, in order to come into view’. Andersen, like the musician in his story, came from a poor provincial family, but he had found in Copenhagen powerful friends who helped him make his way. Kierkegaard disagreed with Andersen’s depiction of genius as fragile, passive, and in need of benefaction; he thought this underestimated its power. He was thinking less of material support – which unlike Andersen he had always taken for granted – than of literary patronage. Having been spurned by Heiberg, he was defiant: ‘for genius is not a rush candle that goes out in a puff of air, but a conflagration that the storm only incites’.

More fundamentally, he criticized Andersen for lacking a ‘life-view’. This was something he used to talk about with Poul Møller, who had insisted that thinkers and artists should distil within their work their own experience of living. Without this experiential anchor, knowledge and erudition, and even beautiful prose, poetry and music, were insubstantial. ‘A life-view is more than experience, which in itself is always fragmentary,’ Kierkegaard explained: ‘it is the transubstantiation of experience; it is an unshakeable certainty in oneself won from all experience.’ And he contrasted a humanistic life-view, such as the philosophy of the Stoics, with a ‘religious’ life-view drawn from ‘deeper experience’: when a person has a religious certainty in himself – a trust, a confidence, a faith – his life gains a ‘heavenly’ as well as an ‘earthly’ orientation. He also suggested, echoing the Romantic literary theory he had imbibed, that a true poet must overcome his own mundane existence by ‘transfiguring’ his personality into something ideal, eternally youthful, ‘an immortal spirit’. ‘It is only this dead and transfigured personality that [can] produce [poetically], not the many-angled, worldly, palpable one,’ he argued. It was easy to recognize the ‘palpable’ Andersen in his writing – and because this man had no life-view, Kierkegaard concluded, ‘the same joyless battle he himself fights in life now repeats itself in his poetry’.

Hans Christian Andersen

Andersen, who was notoriously sensitive, had awaited this review anxiously. Kierkegaard met him from time to time at the Student Association or out on his walks, and soon after Only a Fiddler came out he told him that he admired the novel and intended to review it. Andersen received a copy of From the Papers of One Still Living as soon as it was published in September 1838: he found it ‘difficult to read with its heavy Hegelian style’, but its harsh judgement was clear enough. He took revenge on Kierkegaard – who still then had his funny swept-up hairstyle – by caricaturing him as a Hegelian hairdresser in his ‘Vaudeville in One Act’, which was performed in Copenhagen’s Royal Theatre in 1840. The hairdresser spouted pretentious philosophical jargon, threw in phrases from Kierkegaard’s review of Only a Fiddler, and declared himself ‘an individual depressed by the world’.

Although Andersen was the subject of Kierkegaard’s philosophical dissection, this reflected his wider critique of modern culture, which in turn mirrored his critical reflections on himself. Poul Møller used to argue that it was especially difficult to gain a religious life-view in the present age – and Kierkegaard experienced this difficulty first-hand. By writing as ‘One Still Living’ he suggested that he, like Andersen, was still too palpable, that he had not yet died, transfigured himself, and become immortal as a true poet should. Although his spiritual life had deepened during 1838 – one day that May he had an extraordinary experience of ‘indescribable joy’, and in July he resolved to ‘labour to achieve a far more inward relation to Christianity’ – he was still driven by his eagerness to impress others, and was not yet writing from the depths he had glimpsed.

After his father’s death and the publication of From the Papers of One Still Living, he finally focused on finishing his theology degree. In 1840 he left Nytorv again and leased an apartment on Nørregade, a short walk away on the other side of the Church of Our Lady. That summer, nearly ten years after entering the university, he passed all his exams. He proposed to Regine in September and a few weeks later enrolled in the Royal Pastoral Seminary, where the students had to evaluate one another’s sermons. Kierkegaard’s preaching was judged to be thoughtful and logical, and his delivery dignified and strong – but his peers complained that he ‘moved in too mystical a sphere’ by reflecting on ‘the blessing of silent prayer, the joyousness of contemplation, God’s presence in us’.

That autumn he began to work on his doctoral dissertation, ‘On the Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates’. This was his first sustained piece of philosophical writing, and an important phase in his intellectual development. Like From the Papers of One Still Living, it bore the influence of Poul Møller: it criticized the sweeping nihilism of Romantic irony and argued that Socratic irony was more discerning as it called into question the values of the world. He focused his critique of Romanticism on Friedrich von Schlegel’s experimental novel Lucinde, which celebrated free, passionate love and depicted marriage as an instrument of bourgeois morality that reduces natural desires to a contractual obligation.

Was it a coincidence that he was working on this material during his engagement to Regine? Did his own romantic situation shape his philosophical analysis of Lucinde – or was it the other way around? It was difficult to know how experience and reflection came to mirror one another; indeed, this very question about the connection between ‘ideality’ and ‘actuality’, theory and practice, preoccupied him. How was truth to be discerned within the ideas and meanings which he, like every human being, constantly conjured out of the tangible reality of people, places, things?

In those early days he treated this as an intellectual question; now, in 1848, he regards it more as a divine mystery that has gradually revealed itself through his literary activity. God’s governance, he believes, has interwoven his personal life and his philosophical labours: all this is God’s way of drawing him to the questions and turning points that his soul needs to move through in order to grow, in order to become the self he is meant to be. For although human beings are not ready-made, they do not create themselves either. His life is not entirely determined by God, but he now feels that he will find his true path through the world only by submitting to divine governance.

Yet in 1841 he was more interested in control and mastery than in submission and obedience. At the end of ‘On the Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates’, he advocated a ‘controlled’ use of irony: in art, he argued, Shakespeare and Goethe – and Heiberg – were ‘masters of irony’, for these great writers used the critical power of irony selectively and skilfully, in the service of a particular world view. So what would it be, he asked, to master irony in life? Here it was even more important to control irony, because irony is to existence what doubt is to science: ‘Just as scientists maintain that there is no true science without doubt,’ he asserted, ‘so it may be maintained that no genuinely human life is possible without irony.’ A disciplined, discerning scepticism is essential to scientific method, but if everything is doubted then science becomes impossible. Likewise, Socrates declared that the unexamined life is not worth living – but he knew better than anyone that life must be examined wisely and carefully. Kierkegaard concluded that the Romantic ideal of ‘living poetically’ should be reinterpreted as the mastery of irony in life, as the greatest poets mastered it in their art.

He completed his dissertation in the spring of 1841, and defended it in late September that year. It was Professor Sibbern’s job to organize the committee of examiners, and they included H. C. Ørsted, now celebrated for his discovery of electro-magnetism in 1820 and spending the final years of his career as Rector of the University of Copenhagen. Kierkegaard’s examiners admired his philosophical insight and originality, but thought his satirical style inappropriate. Ørsted reported that, despite its intellectual strengths, ‘On the Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates’ made ‘a generally unpleasant impression’ on him because of its ‘verbosity and affectation’. Nevertheless, the dissertation was deemed acceptable for conferral of the magister degree.

Less than two weeks after he became Magister Kierkegaard, he was in disgrace. In October he made the final break from Regine, and soon left for Berlin. When he arrived there he stayed in the grand Hotel de Saxe before moving to an apartment on Gendarmenmarkt, the central market square. In the middle of Gendarmenmarkt was the Royal Theatre, built twenty years earlier in the style of a Greek temple, reclaimed by the Romantic imagination as a monument to the high culture of Prussia’s most enlightened city. The theatre stood between two eighteenth-century churches, one for the German reformed congregation and the other for French Calvinists. This juxtaposition of classically inspired art and Protestant theology – the aesthetic and the religious – summed up in stone the formation of his soul, right outside his window.

Gendarmenmarkt, Berlin: Neue Kirk (Deutscher Dom) and Royal Theatre

By then writing was his daily habit; in Berlin it also became the only way to communicate with people at home. His long walks with Emil Boesen were replaced by long letters: he wrote to Emil every two or three weeks asking for news of Regine, confiding the turbulent motions of his soul, reporting on the progress of his writing – always urging his friend to reply, and enjoining ‘the deepest secrecy’. People in Copenhagen were gossiping about him, of course; he imagined what they were saying and then responded to these criticisms, which were voiced many more times in his mind than in any parlour, café or street in town. ‘The only thing I can say I miss now and then are our colloquia,’ he wrote to Emil – ‘How good it was to talk myself out once in a while but, as you know, I need a rather long time for that even though I talk quickly. Still, a letter always means a lot, especially when it is the sole means of communication.’

Unlike most people, Emil did not judge him, but Kierkegaard nevertheless wrote pages and pages justifying his decision to break up with Regine. He explained that this crisis had jolted him out of the aesthetic sphere – that this simple matter of another human being had burst the enchanting but ineffectual bubble of possibility in which he had floated for so long. ‘I do not turn her into a poetic subject, I do not call her to mind, but I call myself to account,’ he told Emil in November 1841: ‘I think I can turn anything into a poetic subject, but when it is a question of duty, obligation, responsibility, debt, etc., I cannot and I will not turn these into poetic subjects.’ He did not then feel the bitter resentment towards Regine that had grown within him by the time he returned to Berlin in 1843. If she had broken off the engagement, he remarked, she would have ‘served him’ – but as it was, he must serve her. ‘If it were in her power to surround me with vigilant scouts who always reminded me of her, still she could not be so clearly remembered as she is now in all her righteousness, all her beauty, all her pain.’

Still, in this letter his contrition was edged with triumph – a sense that he had gained a victory over the world by refusing to conform to its demands. ‘In the course of these recent events my soul has received a needed baptism, but that baptism was surely not by sprinkling, for I have descended into the waters; everything has gone black before my eyes, but now I ascend again. Nothing so develops a human being as adhering to a plan in defiance of the whole world.’ He knew, of course, that he was testing Emil’s patience. ‘My dear Emil, if you get angry, please do not hide it from me,’ he urged at the end of this letter. ‘Whether my soul is too egotistical or too great to be troubled by such matters, I do not know, but it would not disturb me … I demand nothing of you except that you feel well, that you feel at one with your soul … I have lost much or robbed myself of much in this world, but I will not lose you.’

During those months in Berlin, his soul rotated not only through different moods but through the different selves summoned into being by his correspondence. In mid-December he wrote three letters on three consecutive days: to his twelve-year-old niece Henriette Lund, to Emil, and to Professor Sibbern. He sent Henriette a sweet, funny letter offering birthday congratulations on ‘a special kind of paper’, decorated with pictures of Berlin’s grand neoclassical museum, theatre and opera house. The following day he resumed the role of omnipotent Romantic poet, sending Emil an update on the ‘tactics’ plotted by his ‘all too inventive brain’ – ‘that her family hates me is good. That was my plan, just as it was also my plan that she, if possible, be able to hate me’ – along with dubious advice on Emil’s own romantic predicament, and a blustering postscript about an attractive Viennese singer who was playing Elvira in Don Giovanni: she looked just like Regine. In his letter to Sibbern he became a deferential, diligent student, reporting on philosophy lectures he had attended by Steffens, Philip Marheineke, Karl Werder and Schelling.

Being Uncle Søren undoubtedly brought out the best in him. From Berlin he kept up a regular correspondence with all his nieces and nephews back in Copenhagen – the children of his deceased sisters Petrea and Nicolene – and his letters to them were thoughtful and affectionate. He sent fourteen-year-old Sophie a teasing but kindly reply to her excited letter about going to a ball. To Carl, aged eleven, he wrote about the big dogs which pulled carriages transporting milk from the countryside, the noisy squirrels racing round the Tiergarten, the ‘innumerable goldfish’ in the canal, while Wilhelm, aged ten, received an elegant letter commending his neat, clear handwriting and correcting a few spelling errors. In late December 1841 Kierkegaard wrote to Carl and his elder brother Michael about Christmas in Berlin, which he had spent dining with ‘all the Danes’ at the Belvedere: ‘We especially tried to cheer ourselves up and to bring back memories of home by eating apple dumplings. We also had a Christmas tree.’ He encouraged Carl, whose last letter had been laughably short, to write again – ‘just write freely about whatever occurs to you, do not be shy … Please tell me next time what you got for Christmas and among other things what came from me … I suppose there has already been frost in Copenhagen for a long time, and by now you must have been out on the ice several times. All that kind of thing interests me. This you might tell me about.’ After Christmas, days of ‘terrible cold’ gave way to ‘beautiful winter weather’, and in mid-January Carl and Michael received reports of ice-skating, and of coaches and carriages converted into sleighs to ride through Berlin’s snowy streets. It was a ‘delightful’ spectacle, though Kierkegaard found it too cold to travel this way himself.

None of his relationships, none of his selves, were free of his anxiety about Regine. He knew that Professor Sibbern would be in touch with her, that his nieces and nephews visited her. After Christmas his letters to Emil became even longer, and even more riddled with conflict and confusion. He told Emil, as he told himself, that he was in control of the situation: ‘I hold my life poetically in my hand … My life divides itself into chapters, and I can provide an exact heading for each as well as state its motto. For the present it proclaims: “She must hate me.”’ Everything, he explained, was directed to this end:

In the company of the Danes here in Berlin I am always cheerful, merry, gay, and have ‘the time of my life’, etc. And even though everything churns inside me so that it sometimes seems that my feelings, like water, will break the ice with which I have covered myself, and even though there is at times a groan within me, each groan is instantly transformed into something ironical, a witticism, etc., the moment anybody else is present … [for] my plan demands it. Here a groan might reach the ear of a Dane, he might write home about it, she might possibly hear of it, it might possibly damage the transitional process.

As the weeks went by Berlin’s bitter winter became increasingly hard to bear. The east wind was freezing, he complained to Emil in February 1842, and he had been unable to get warm for several days and nights. Every adversity compounded his spiritual trial; he returned again and again to thoughts of Regine:

Cold, some insomnia, frayed nerves, disappointed expectations of Schelling, confusion in my philosophical ideas, no diversion, no opposition to excite me – that is what I call the acid test. One learns to know oneself … I broke the engagement for her sake. That became my consolation. And when I suffered the most, when I was completely bereft, then I cried aloud in my soul: ‘Was it not good, was it not a godsend that you managed to break the engagement? If this had continued, then you would have become a lifelong torment for her.’

Yet in the last pages of this letter he fantasized about returning to Regine. He could no longer think about her without considering the opinion of the whole town: he imagined that he would be ‘hated and detested’, that he would ‘become a laughing stock’, or even that people would say he had something decent about him after all – which, he insisted, worried him most of all. ‘This winter in Berlin will always have great significance for me,’ he eventually concluded. ‘I have done a lot of work. I have had three or four hours of lectures every day, a daily language lesson, and have still written so much, and have read a lot, I cannot complain. And then all my suffering, all my monologues!’

At the end of February he sent Emil one last letter from his exile. His soul had entered a new phase: now he was decisive, clear, cheerful:

My dear Emil,

Schelling talks endless nonsense … I am leaving Berlin and hastening to Copenhagen, but not, you understand, to be bound by a new tie, oh no, for I feel more strongly than ever that I need my freedom. A person with my eccentricity should have his freedom until he meets a force in life that can bind him. I am coming to Copenhagen to complete Either/Or. It is my favourite idea, and in it I exist …

After a few false starts, his authorship began during that first visit to Berlin – and he started to become, as he now puts it, ‘the person I am’. His soul was no longer merely rotating: he had leapt into a new, religious sphere of existence, propelled by the engagement crisis. It was not theology, nor philosophy, nor art, but the break with Regine that had opened up his relationship to God, and allowed him to grow into it. In dating his authorship from the publication of Either/Or early in 1843, he is setting aside his earlier writings, for these did not express the religious life-view, wrought from a profound personal experience, that he described in From the Papers of One Still Living. The author of that review could theorize about an ‘unshakeable certainty in oneself’, but he did not yet possess it.

Just as the break with Regine was inseparable from the beginning of his work as an author, so she has become entangled in its ending. During this gruelling summer of 1848, his thoughts have returned to her again and again; his anxiety about finalizing his authorship seems to contain the huge store of anxieties he has felt about Regine for the last ten years. Beneath them all is longing, for something that continues to elude him. Just a few days ago, he took a carriage through the country lanes all the way up to Fredensborg, where he knew the Olsens were staying – ‘An inexplicable presentiment took me there, I was so happy and almost sure of meeting the family there’ – and sure enough he bumped into Regine’s father. ‘I go up to him and say: Good day Councillor Olsen, let us talk together. He took off his hat and greeted me but then brushed me aside and said: I do not wish to speak with you. Oh, there were tears in his eyes, and he spoke these words with tormented feeling. I went towards him, but he started to run so fast that, even if I had wanted to, it would have been impossible to catch up with him.’

It is impossible to catch up with the past – to grasp it, to change it, to pull it into a new shape. All he can do is recollect it, write it out, and try to discern its meaning. ‘At some point,’ he resolves, ‘I must give a clear explanation of myself as an author, of what I say I am, of how I understand myself as having been a religious author from the start.’ Pacing through his stuffy Rosenborggade apartment over these August weeks, he has understood more clearly than before how he has been ‘educated’ by his own writing. Ever since his student days he has been interested in character development and spiritual growth, combining the pietists’ emphasis on ‘upbuilding’ and ‘awakening’ with a Romantic faith in art as a means to self-cultivation. Now he grasps how he became an author, and how he has grown religiously through his writing: ‘I have been brought up and developed in the process of my work, and personally I have become committed more and more to Christianity.’ And, having brought his authorship to an end with his article about Madame Heiberg and her two Juliets, he needs others to understand that his writing was religious from the start – that it was a religious crisis which prepared the way for Either/Or, and for his own ‘beginning’. ‘I began with the most profound religious impression – alas, I who, when I began, bore the entire responsibility for another human being’s life and understood this as God’s punishment of me … In a decisive sense I had experienced the pressures that turned me away from the world before I started Either/Or.’

Although he has exhausted himself with deliberations on his authorship, he feels the exhilaration of fresh beginnings – fresh thoughts, fresh pages – rising within him. ‘How often haven’t I had happen what has just now happened to me again? Then I sink into the most profound sufferings of melancholia; one or another thought gets so tangled for me that I cannot untangle it, and because it relates to my own existence I suffer indescribably. And then, after a little time has passed, it is as if a boil has burst – and inside is the most wonderful and fruitful productivity, precisely what I have use for at the moment.’ It is not yet clear whether he needs to give an account of his authorship in order to put it to rest – one final postscript – or in order to close the chapter of the last five years of writing, so that he can open a new one.