DECISION MAKING

Forecasting the Future (and Winning at Poker) with Bayesian Psychology

The dealer looks at Annie Duke and waits for her to say something. There is a pile of chips worth $450,000 in the middle of the table and nine of the world’s best poker players—all men, except for Annie—impatiently waiting for her to bet. It’s the 2004 Tournament of Champions, a televised competition with $2 million to the winner. There is no prize for second place.

The dealer hasn’t put down any communal cards yet, and Annie is holding a pair of tens. Her hand is strong—strong enough that she has already shoved most of her chips into the pot. Now she has to decide if she wants to bet everything. All the other players have folded except for one—Greg Raymer, aka “the FossilMan,” a rotund gentleman from Connecticut who carries pieces of petrified bark in his pockets and wears sunglasses with holographic lizard eyes.

Annie doesn’t know what cards the FossilMan is holding. Until a few seconds ago, based on how things were proceeding, she figured she was going to win this hand. But then the FossilMan pushed everything onto the pot and threw a wrench in Annie’s plans. Has the FossilMan been playing her this whole time? Luring her into bigger and bigger bets while waiting to pounce? Or is he trying to scare her off with a wager so large he thinks she’ll get spooked and walk away?

Everyone is staring at Annie. She has no idea what to do.

She could fold. But that would mean forfeiting the tens of thousands of dollars she’s spent to get to this table, all the progress she’s made over the past nine hours, everything she’s worked so hard to earn.

Or she could match his wager and bet everything. If she loses, she’ll be knocked out of the tournament. If it pays off, though, and she wins this hand, she’ll instantly become the tournament’s frontrunner, a step closer to paying for her kids’ school bills and her mortgage, not to mention her messy divorce and all the uncertainties that give her stomachaches at night.

She looks again at the mountain of chips on the table and feels a pressure rising in her throat. She’s had panic attacks all her life, breakdowns so severe that she used to lock herself inside her apartment and refuse to leave. Twenty years ago, during her sophomore year at Columbia University, she became so anxious she walked into a hospital, begged them to admit her, and didn’t come out for two weeks.

Forty-five seconds pass while Annie tries to figure out what to do. “I’m so sorry,” she says. “I know I’m taking too long. This is just a really hard decision.”

Annie focuses on her pair of tens. She thinks about what she knows and doesn’t know. What Annie likes about poker are the certainties. The trick to this game is making predictions, imagining alternative futures and then calculating which ones are most likely to come true. Statistics make Annie feel in control. She might not know exactly what’s coming, but she knows the precise likelihoods of being right or wrong. The poker table feels serene.

And now the FossilMan has blown that peacefulness to hell by making a bet that doesn’t match any of the scenarios inside Annie’s head. She has no idea how to gauge what is most likely to occur. She’s frozen.

“I’m really sorry,” she says. “I just need a second more.”

Many afternoons during Annie’s childhood, her mother would sit at the kitchen table with a pack of cigarettes, a glass of scotch, and a deck of cards, and play hand after hand of solitaire until the alcohol was gone and the ashtray was full. Then she would stagger to the couch and fall asleep.

Annie’s father was an English teacher at St. Paul’s School in New Hampshire, a boarding school for the scions of senators and CEOs. Her family lived in a house attached to one of the dorms and so whenever her parents fought about her mom’s drinking or her father’s lack of money—which they did frequently—Annie was sure her classmates could overhear. She often felt like an outcast at the school, too poor to vacation with the rich kids, too smart to bond with the popular girls, too anxious to be comfortable among the hippies, too interested in math and science for student government. For Annie, the key to surviving amid the shifting tectonics of teenage popularity was learning to forecast. If she could predict which students’ social capital was rising or falling, it was easier to avoid the infighting. If she could predict when her parents were arguing or her mom was drinking, she would know if it was safe to bring classmates home.

“When you have an alcoholic parent, you spend a lot of time thinking about what’s coming,” Annie told me. “You never take for granted that you’ll get dinner or that someone will tell you when to go to bed. You’re always waiting for everything to fall apart.”

After graduation, Annie left for college at Columbia and soon discovered the psychology department. Here, at last, was what she had been looking for. There were classes that reduced human behavior to understandable rules and social formulas; teachers who gave lectures on the different categories of personality and why anxieties emerge; studies about the impact of having an alcoholic parent. She felt like she was starting to understand why she sometimes had panic attacks, why it occasionally felt impossible for her to leave her bed, why she carried this dread that something bad might happen at any time.

Psychology, at that moment, was undergoing a transformation brought on by discoveries in cognitive sciences that were bringing a scientific rigor to understanding behaviors that had long seemed immune to methodical analysis. Psychologists and economists were working together to understand the codes that explain why people do what they do. Some of the most exciting research—work that would eventually win a Nobel Prize—was focused on studying how people make decisions. Why, researchers wondered, do some people decide to have children when the costs, in terms of money and hard work, are so obvious, and the payoffs, such as love and contentment, are so hard to calculate? How do people decide to send their kids to expensive private schools instead of free public ones? Why does someone decide to get married after playing the field for years?

Many of our most important decisions are, in fact, attempts to forecast the future. When we send a child to private school, it is, in part, a bet that money spent today on schooling will yield happiness and opportunities in the future. When we decide to have a baby, we’re forecasting that the joy of becoming a parent will outweigh the cost of sleepless nights. When we choose to get married—though it may seem completely unromantic—we are, at some level, calculating that the benefits of settling down are greater than the opportunity of seeing who else comes along. Good decision making is contingent on a basic ability to envision what happens next.

What fascinated psychologists and economists was how frequently people managed, in the course of their everyday lives, to choose among various futures without becoming paralyzed by the complexities of each choice. What’s more, it appeared that some people were more skilled than others at envisioning various futures and choosing the best ones for themselves. Why were some people able to make better decisions?

When Annie graduated from college, she enrolled in a PhD program in cognitive psychology at the University of Pennsylvania and began collecting grants and publications. After five years of hard work and a successful run of papers and awards, with only months to go to her doctorate, she was invited to give a series of “job talks” at several universities. If she performed well, she was practically guaranteed a prestigious professorship.

The night before her first speech at New York University, she took the train to Manhattan. She had been feeling anxious all week. At dinner she began throwing up. She waited an hour, drank a glass of water, and threw up again. She couldn’t turn off her anxiety. She couldn’t stop thinking that she was making a mistake, that she didn’t want to be a professor, that she was only doing all this because it had seemed like the safest, most predictable path. She called NYU to postpone her talk. Her fiancé flew to Manhattan and took her back to Philadelphia, where she checked into a hospital. She was discharged weeks later, but even then her anxiety was like a hot stone in her stomach. She went straight from the hospital to a classroom at Penn where she was supposed to teach and somehow made it through the lecture, so nauseous and jumpy she almost fainted. She couldn’t teach another class, she decided. She couldn’t give her job talks. She couldn’t become a professor.

She shoved her research into the trunk of her car, sent a note to her professors saying that she would be hard to reach for a while, and drove west. Her fiancé had found a house that cost $11,000 outside Billings, Montana. When Annie arrived, she determined that, even at that price, they had paid too much. But by then, she was too exhausted to do anything about it. She put her dissertation materials into the closet and settled onto the couch. Her only goal was to think as little as possible.

A few weeks later, her brother, Howard Lederer, called to invite her to Las Vegas for a vacation. Howard was a professional poker player, and every spring for the past few years, he had flown Annie out to sit by the swimming pool of the Golden Nugget while he played in a tournament. Whenever she got bored, she would wander inside to watch him compete or play a few hands of poker herself. When he called this year, however, Annie said she was too sick to make the trip.

Howard was concerned. Annie loved Vegas. She never turned down a trip.

“Why don’t you at least find a local poker game?” he said. “It might help you get out of the house.”

By then she was married, and so she asked her husband to make some inquiries. They learned there was a bar in Billings named the Crystal Lounge where retired ranchers, construction workers, and insurance agents played poker every afternoon in the basement. It was a smoke-filled, joyless dungeon. Annie went one afternoon and loved it. She went again a few days later and walked out fifty dollars richer. “Playing poker down there was this combination of math, which I loved, and all of the cognitive science stuff I had been doing in graduate school,” Annie told me. “You could watch people try to bluff each other and hide their excitement when they got a good hand, and all these other kinds of behaviors we’d spent hours talking about in classes. Every night, I would call my brother and talk through the hands I had played that day, and he would explain my mistakes, or how someone else had figured out my game and had started using that against me or what I should do different next time.” Initially, she wasn’t very good. But she won often enough to keep going. She noticed that her stomach never hurt at the poker table.

Pretty soon, she was going to the Crystal Lounge every weekday, like a job, arriving at three P.M. and staying until midnight, taking notes and testing strategies. Her brother sent her a check for $2,400 with the agreement that he would get half her winnings. She was up $2,650 by the end of the first month even after his cut. The next spring, when he invited her to Vegas, she drove fourteen hours, bought a seat in a tournament, and by the end of the first day had $30,000 in chips.

Thirty thousand dollars was more than Annie had ever earned in a full year as a grad student. She understood poker—understood it better than many of the people she was playing against. She understood that a losing hand isn’t necessarily a loss. Rather, it’s an experiment. “The thing I had figured out by that point was the difference between intermediate and elite players,” Annie told me. “At the intermediate level, you want to know as many rules as possible. Intermediate players crave certainty. But elite players can use that craving against them, because it makes intermediate players more predictable.

“To be elite, you have to start thinking about bets as ways of asking other players questions. Are you willing to fold right now? Do you want to raise? How far can I push before you start acting impulsively? And when you get an answer, that allows you to predict the future a little bit more accurately than the other guy. Poker is about using your chips to gather information faster than everyone else.”

By the end of the tournament’s second day, Annie had $95,000 in chips. She finished in twenty-sixth place, ahead of hundreds of professionals, some with decades of experience. Three months later, she and her husband moved to Las Vegas. At some point, she called her professors at Penn and told them she wasn’t coming back.

A full minute has passed. Annie still has a pair of tens. If the FossilMan is holding a higher pair—say, two queens—and Annie stays in the hand, it’s almost certain she’ll be eliminated from the Tournament of Champions. But if she wins the hand, she’ll become the table’s chip leader.

All of the odds and probability charts floating around Annie’s head are telling her to do one thing: Match the FossilMan’s bet. But every time Annie has asked the FossilMan a question during this tournament by placing a wager, he’s answered with a highly rational response. He’s never put everything on the line without a good reason. Now, in this hand, he’s pushed all of his chips into the pot, even as Annie has raised again and again.

Annie is aware that the FossilMan knows how hard it is for her to back down at this point. He knows that, unlike some of the other people at this table, she isn’t in the Poker Hall of Fame. This is her first time in front of a million television viewers. He might even know that she’s worried she doesn’t belong here at all, that she suspects she was only invited because the TV producers wanted a woman at the table.

Annie suddenly realizes she’s been thinking about this hand wrong all along. The FossilMan has been betting as if he has a good hand because, in fact, he has a good hand. Annie has been overthinking—or, at least, she thinks she’s been overthinking. She’s not sure.

She looks at her pair of tens, looks at the $450,000 on the table, and folds. The FossilMan takes the money. Annie has no idea if she just made a good or bad choice because the FossilMan doesn’t have to show anyone his cards. Another player leans over. You completely misread the situation, he whispers to her. If you had stayed in, you would have won.

A few hands later, Annie has already folded when the FossilMan, with a ten and a nine, bets all his chips once again. It’s a smart play, the right move, but as the other cards fall on the table, they go against him. Even the smartest poker players can be undone by bad luck. Probabilities can help you forecast likelihoods, but they can’t guarantee the future. Just like that, the FossilMan is out of the tournament. As he stands to leave, he leans over to Annie.

“I know the hand you had earlier was really hard for you,” he tells her. “I want you to know that I had two kings and you made a good fold.”

When he says that, the knot of panic in her stomach melts. She’s been distracted ever since she folded against him. She’s been second-guessing herself, turning the hand over in her mind, trying to figure out if she played it right or wrong. Now her head is back in the game.

It’s normal, of course, to want to know how things will turn out. It’s scary when we realize how much rides on choices where we can’t predict the future. Will my baby be born healthy or sick? Will my fiancée and I still love each other ten years from now? Does my kid need private school or will the local public school teach her just as much? Making good decisions relies on forecasting the future, but forecasting is an imprecise, often terrifying, science because it forces us to confront how much we don’t know. The paradox of learning how to make better decisions is that it requires developing a comfort with doubt.

There are ways, however, of learning to grapple with uncertainty. There are methods for making a vague future more foreseeable by calculating, with some precision, what you do and don’t know.

Annie is still alive at the Tournament of Champions. She has enough chips to stay in the game. The dealer gives each player their next cards and another hand begins.

II.

In 2011, the federal Office of the Director of National Intelligence approached a handful of universities with grant money and asked them to participate in a project “to dramatically enhance the accuracy, precision, and timeliness of intelligence forecasts.” The idea was that each school would recruit a team of foreign affairs experts, and then ask them to make predictions about the future. Researchers would study who made the most accurate forecasts and, crucially, how they did it. Those insights, the government hoped, would help CIA analysts become better at their jobs.

Most of the universities that participated in the program took a standard approach. They sought out professors, graduate students, international policy researchers, and other specialists. Then they gave them questions no one yet knew the answers to—Will North Korea reenter arms talks by the end of the year? Will the Civic Platform party win the most seats in the Polish parliamentary elections?—and watched how they went about answering. Studying various approaches, everyone figured, would provide the CIA with some fresh ideas.

Two of the universities, however, took a different tack. A group of psychologists, statisticians, and political scientists from the University of Pennsylvania and the University of California–Berkeley, working together, decided to use the government’s money as an opportunity to see if they could train regular people to become better forecasters. This group called themselves “the Good Judgment Project,” and rather than recruit specialists, the GJP solicited thousands of people—lawyers, housewives, master’s students, voracious newspaper readers, and enrolled them in online forecasting classes that taught them different ways of thinking about the future. Then, after the training, those participants were asked to answer the same foreign affairs questions as the experts.

For two years, the GJP conducted training sessions, watched people make predictions, and collected data. They tracked who got better, and how performance changed as people were exposed to different types of tutorials. Eventually, the GJP published their findings: Giving participants even brief training sessions in research and statistical techniques—teaching them various ways of thinking about the future—boosted the accuracy of their predictions. And most surprising, a particular kind of lesson—training in how to think probabilistically—significantly increased people’s abilities to forecast the future.

The lessons on probabilistic thinking offered by the GJP had instructed participants to think of the future not as what’s going to happen, but rather as a series of possibilities that might occur. It taught them to envision tomorrow as an array of potential outcomes, all of which had different odds of coming true. “Most people are sloppy when they think about the future,” said Lyle Ungar, a professor of computer science at the University of Pennsylvania who helped oversee the GJP. “They say things like, ‘It’s likely we’ll go to Hawaii for vacation this year.’ Well, does that mean that it’s 51 percent certain? Or 90 percent? Because that’s a big difference if you’re buying nonrefundable tickets.” The goal of the GJP’s probabilistic training was to show people how to turn their intuitions into statistical estimates.

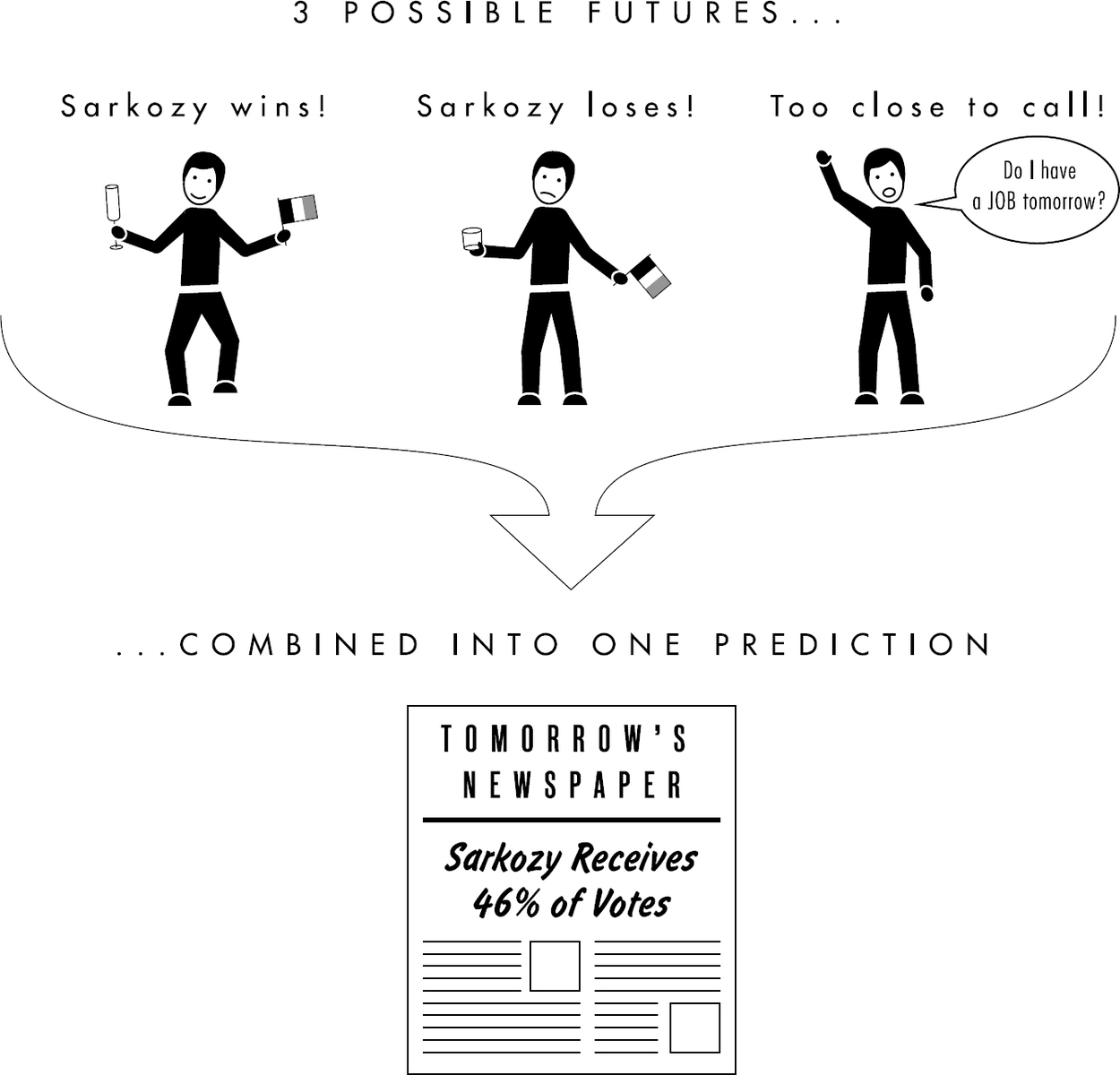

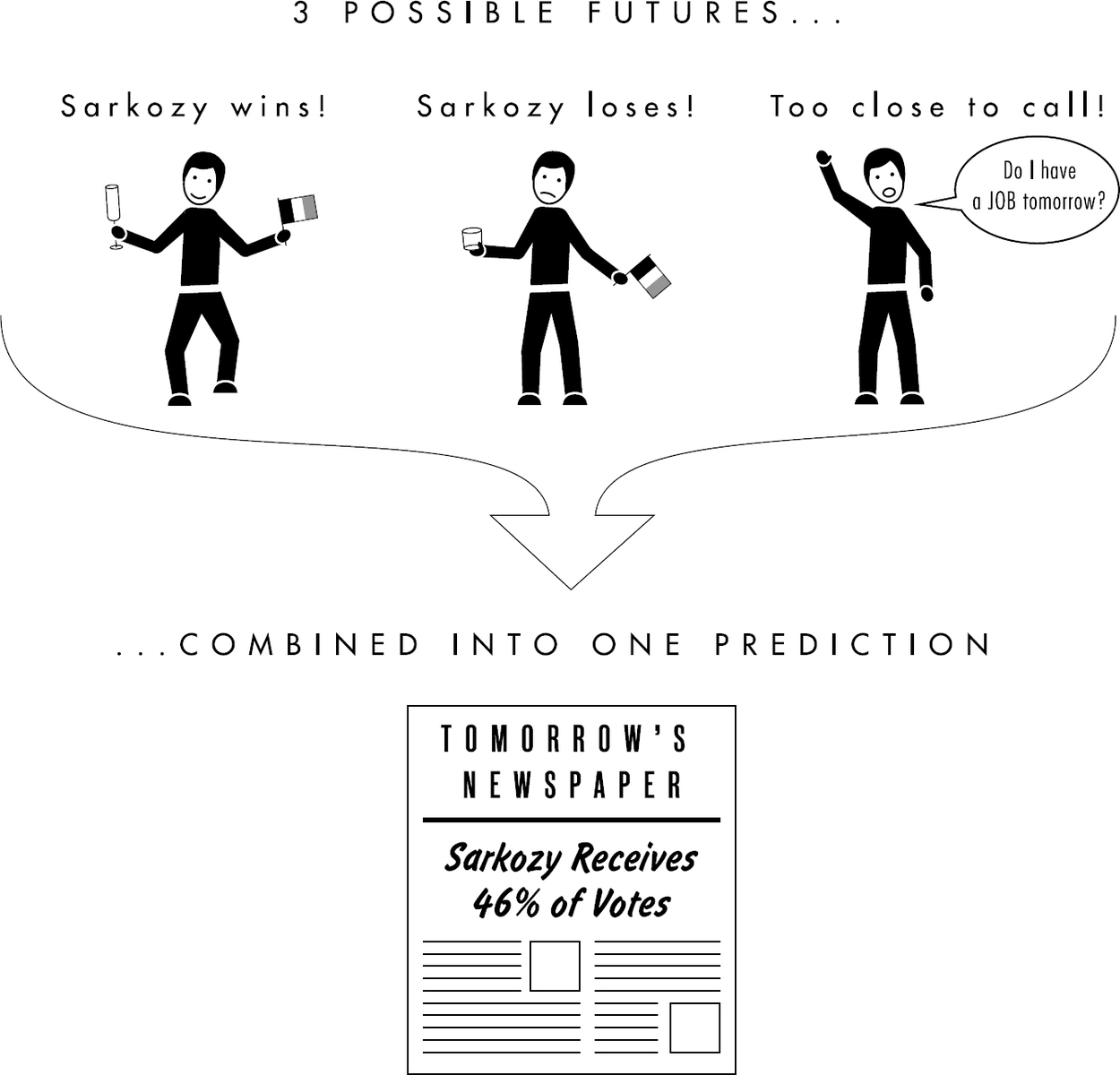

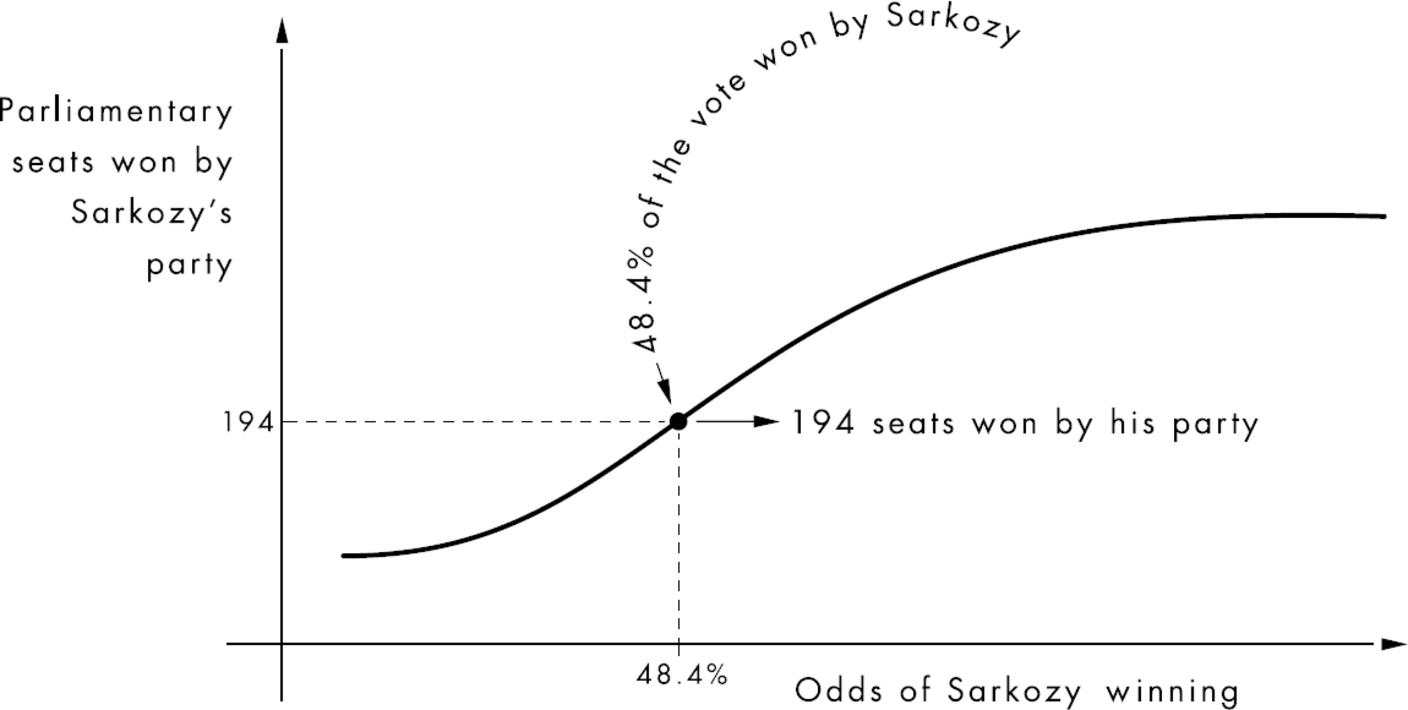

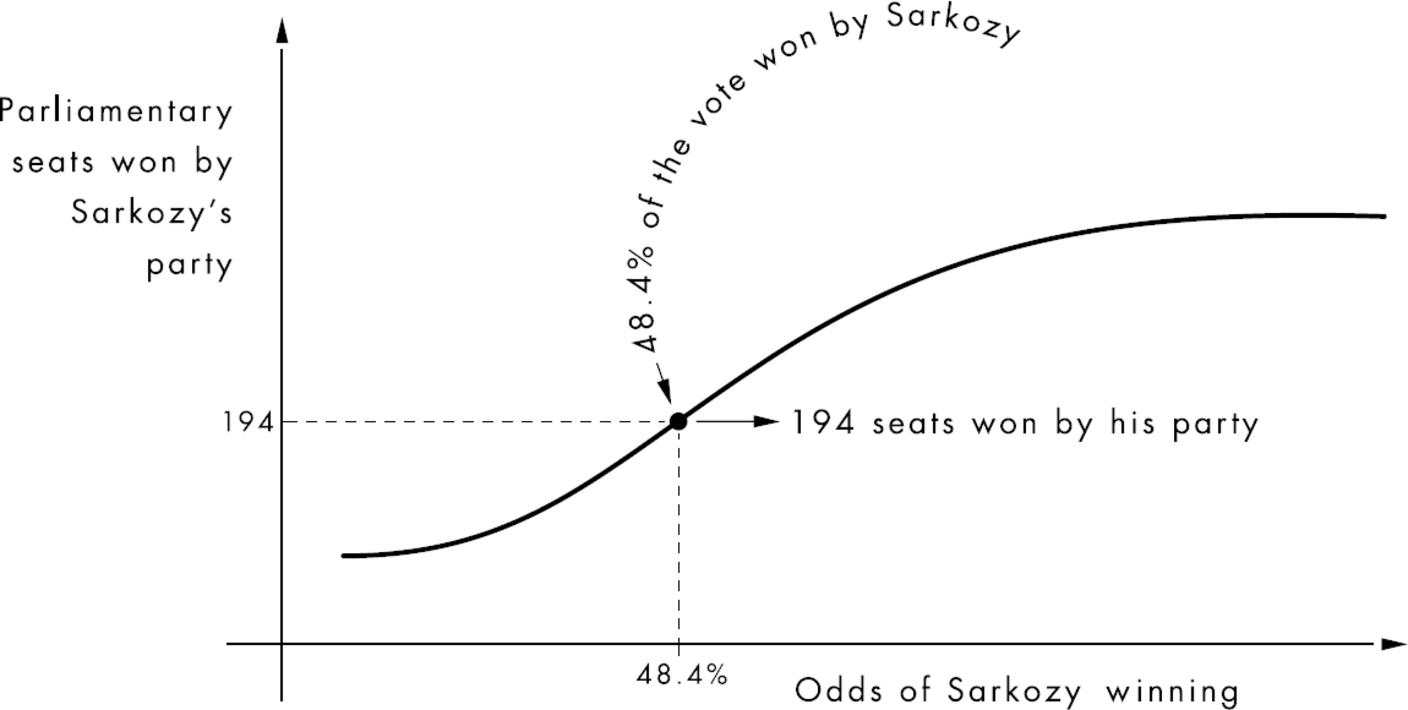

One exercise, for instance, asked participants to analyze if the French president Nicolas Sarkozy would win reelection in an upcoming vote.

The training indicated that, at a minimum, there were three variables someone should consider in predicting Sarkozy’s reelection chances. The first was incumbency. Data from previous French elections indicated that an incumbent such as President Sarkozy, on average, can expect to receive 67 percent of the vote. Based on that, someone might forecast that Sarkozy is 67 percent likely to remain in office.

But there were other variables to take into account, as well. Sarkozy had fallen into disfavor among French voters, and pollsters had estimated that, based on low approval ratings, Sarkozy’s reelection chances were actually 25 percent. Under that logic, there was a three-quarters chance he would be voted out. It was also worth considering that the French economy was limping along, and economists guessed that, based on economic performance, Sarkozy would garner only 45 percent of the vote.

So there were three potential futures to consider: Sarkozy could earn 67 percent, 25 percent, or 45 percent of the votes cast. In one scenario, he would win easily, in another he would lose by a wide margin, and the third scenario was a relatively close call. How do you combine those contradictory outcomes into one prediction? “You simply average your estimates based on incumbency, approval ratings, and economic growth rates,” the training explained. “If you have no basis for treating one variable as more important than another, use equal weighting. This approach leads you to predict [(67% + 25% + 45%)/3] = approximately a 46% chance of reelection.”

Nine months later, Sarkozy received 48.4 percent of the vote and was replaced by François Hollande.

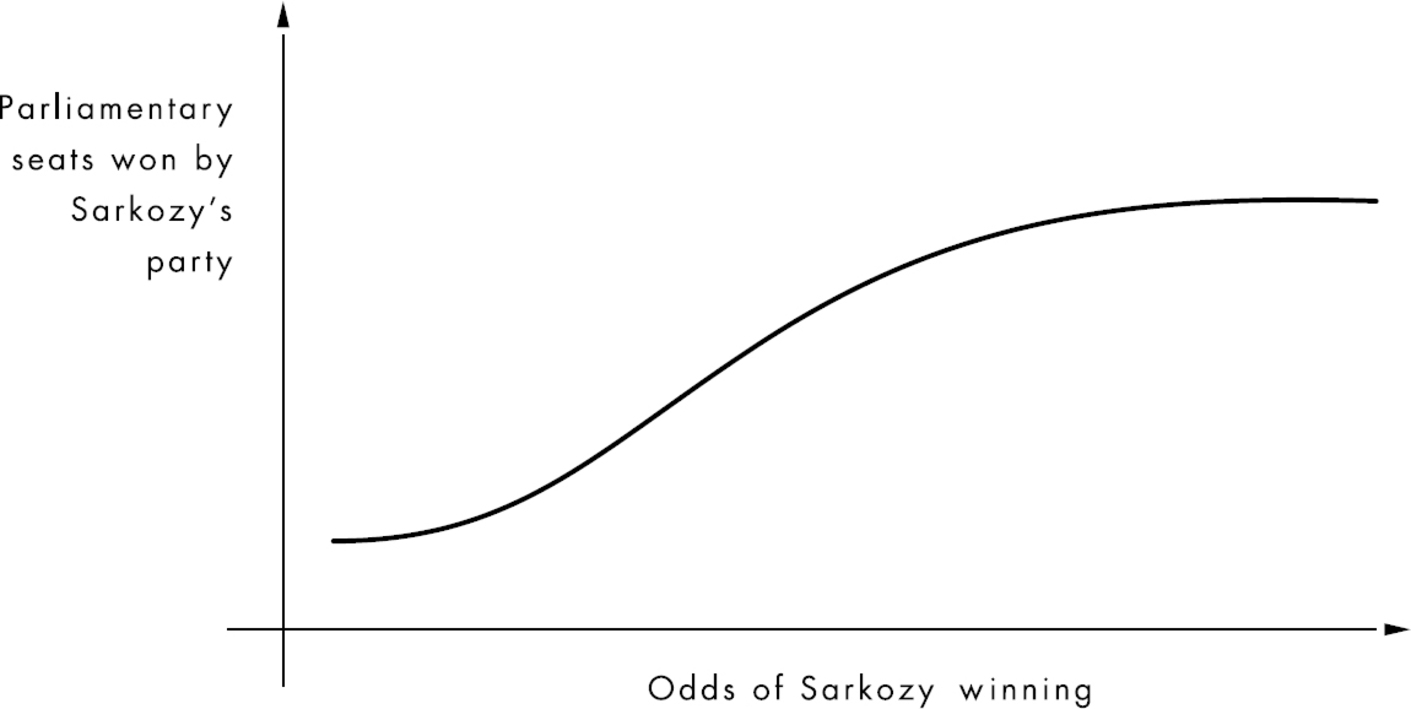

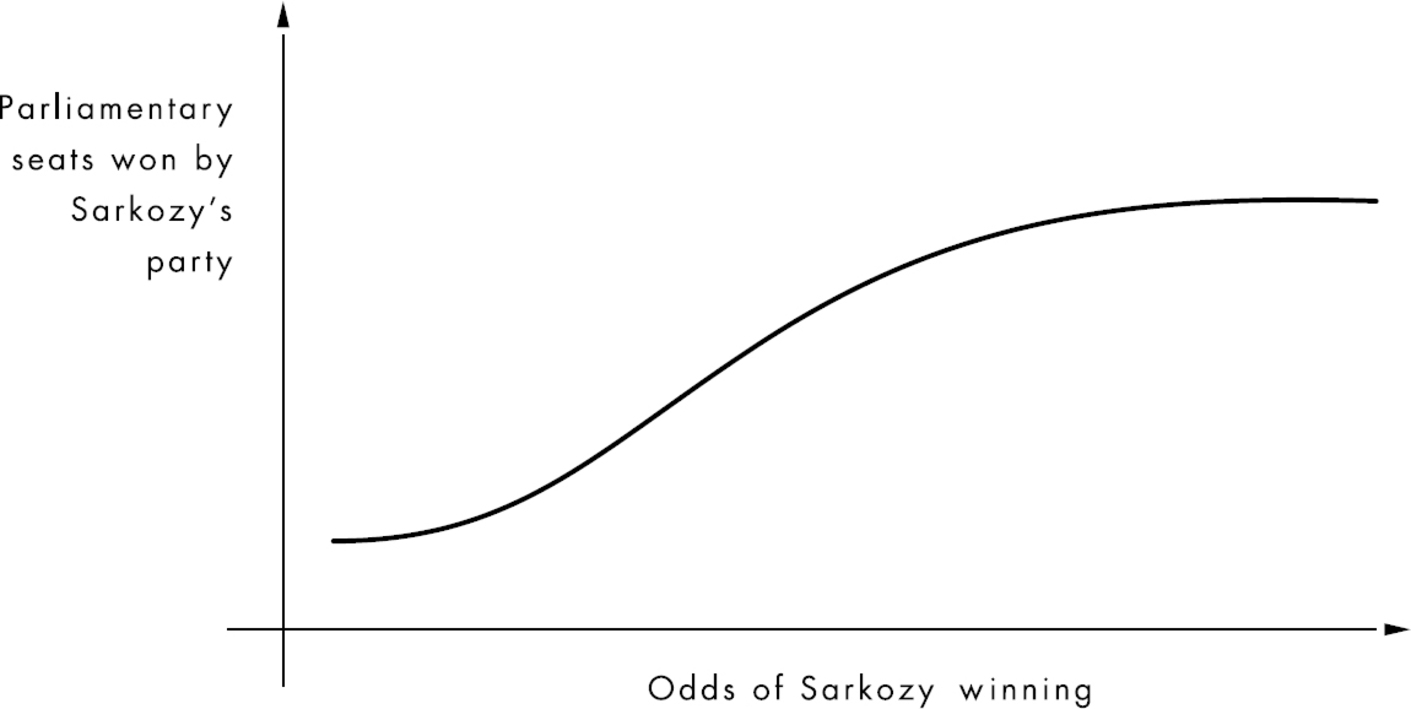

This is the most basic kind of probabilistic thinking, a simplistic example that teaches an underlying idea: Contradictory futures can be combined into a single prediction. As this kind of logic gets more sophisticated, experts usually begin speaking about various outcomes as probability curves—graphs that show the distribution of potential futures. For instance, if someone was asked to guess how many seats Sarkozy’s party was going to win in the French parliament, an expert might describe the possible outcomes as a curve that shows how the likelihood of winning parliamentary seats is linked to Sarkozy’s odds of remaining president:

In fact, when Sarkozy lost the election, his party, the Union pour un Mouvement Populaire, or UMP, also suffered at the polls, claiming only 194 seats, a significant decline.

The GJP’s training modules instructed people in various methods for combining odds and comparing futures. Throughout, a central idea was repeated again and again. The future isn’t one thing. Rather, it is a multitude of possibilities that often contradict one another until one of them comes true. And those futures can be combined in order for someone to predict which one is more likely to occur.

This is probabilistic thinking. It is the ability to hold multiple, conflicting outcomes in your mind and estimate their relative likelihoods. “We’re not accustomed to thinking about multiple futures,” said Barbara Mellers, another GJP leader. “We only live in one reality, and so when we force ourselves to think about the future as numerous possibilities, it can be unsettling for some people because it forces us to think about things we hope won’t come true.”

Simply exposing participants to probabilistic training was associated with as much as a 50 percent increase in the accuracy of their predictions, the GJP researchers wrote. “Teams with training that engaged in probabilistic thinking performed best,” an outside observer noted. “Participants were taught to turn hunches into probabilities. Then they had online discussions with members of their team [about] adjusting the probabilities, as often as every day….Having grand theories about, say, the nature of modern China was not useful. Being able to look at a narrow question from many vantage points and quickly readjust the probabilities was tremendously useful.”

Learning to think probabilistically requires us to question our assumptions and live with uncertainty. To become better at predicting the future—at making good decisions—we need to know the difference between what we hope will happen and what is more and less likely to occur.

“It’s great to be 100 percent certain you love your girlfriend right now, but if you’re thinking of proposing to her, wouldn’t you rather know the odds of staying married over the next three decades?” said Don Moore, a professor at UC-Berkeley’s Haas School of Business who helped run the GJP. “I can’t tell you precisely whether you’ll be attracted to each other in thirty years. But I can generate some probabilities about the odds of staying attracted to each other, and probabilities about how your goals will coincide, and statistics on how having children might change the relationship, and then you can adjust those likelihoods based on your experiences and what you think is more or less likely to occur, and that’s going to help you predict the future a little bit better.

“In the long run, that’s pretty valuable, because even though you know with 100 percent certainty that you love her right now, thinking probabilistically about the future can force you to think through things that might be fuzzy today, but are really important over time. It forces you to be honest with yourself, even if part of that honesty is admitting there are things you aren’t sure about.”

When Annie started playing poker seriously, it was her brother who sat her down and explained what separated the winners from everyone else. Losers, Howard said, are always looking for certainty at the table. Winners are comfortable admitting to themselves what they don’t know. In fact, knowing what you don’t know is a huge advantage—something that can be used against other players. When Annie would call Howard and complain that she had lost, had suffered bad luck, that the cards had gone against her, he would tell her to stop whining.

“Have you considered that you might be the idiot at the table who’s looking for certainty?” he asked.

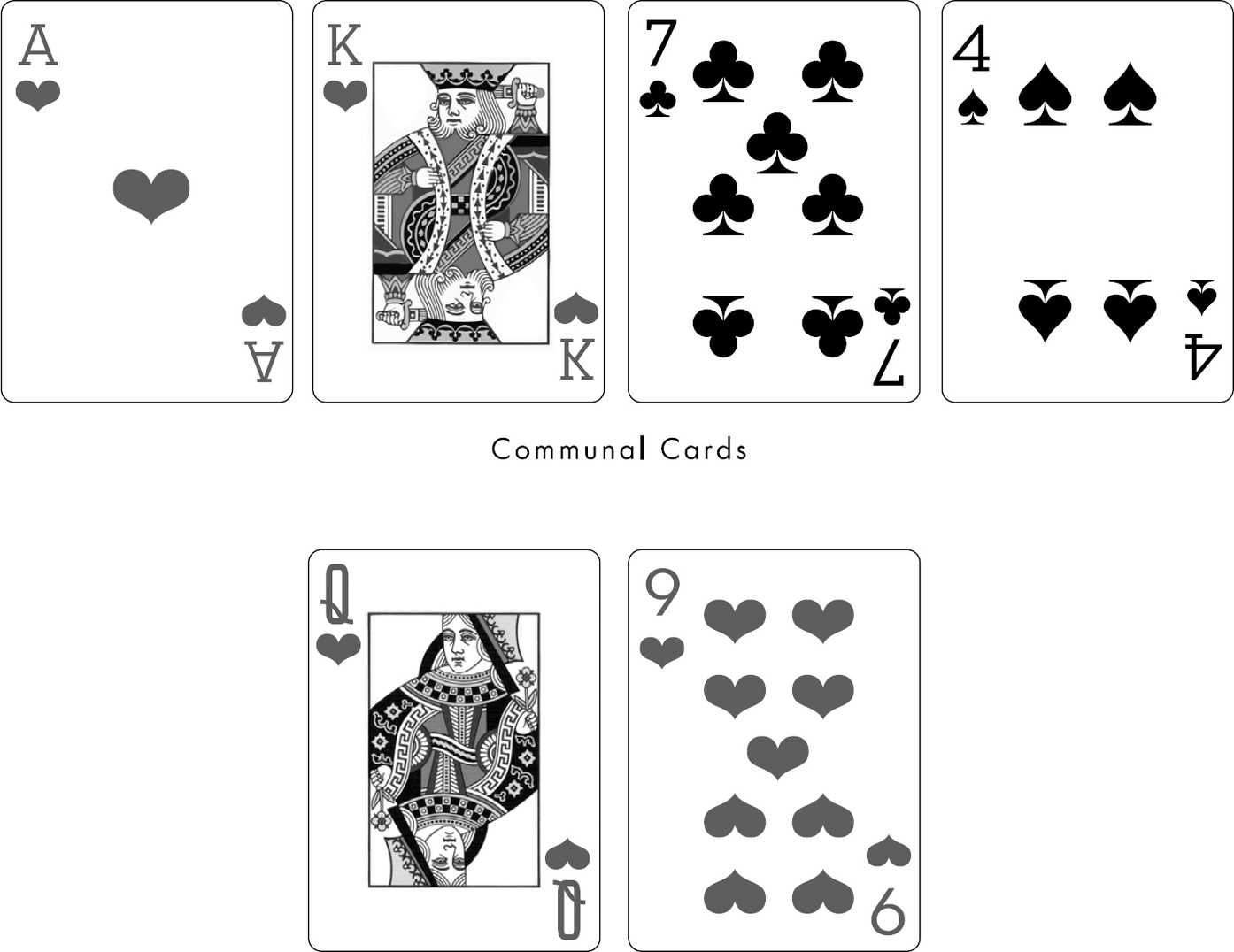

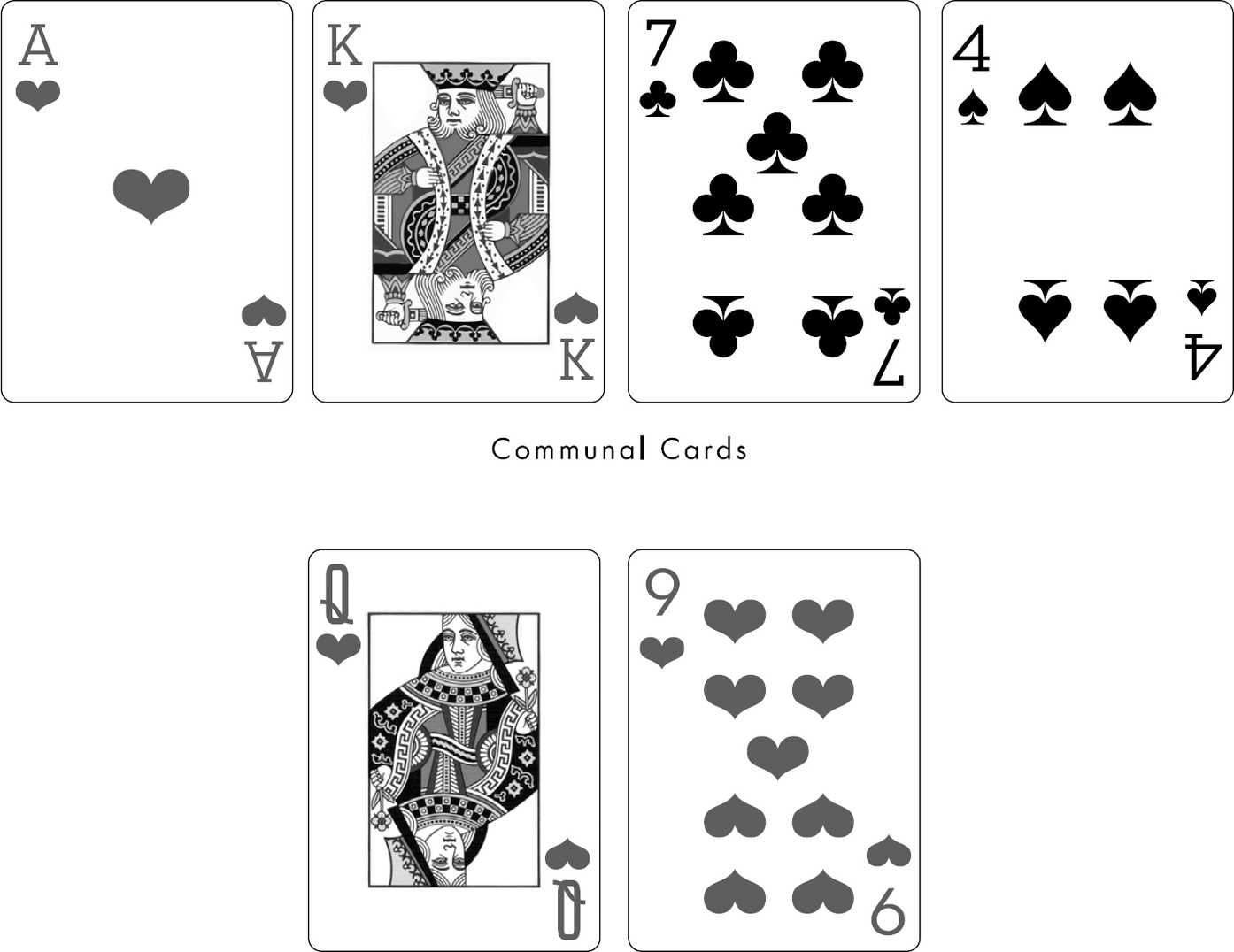

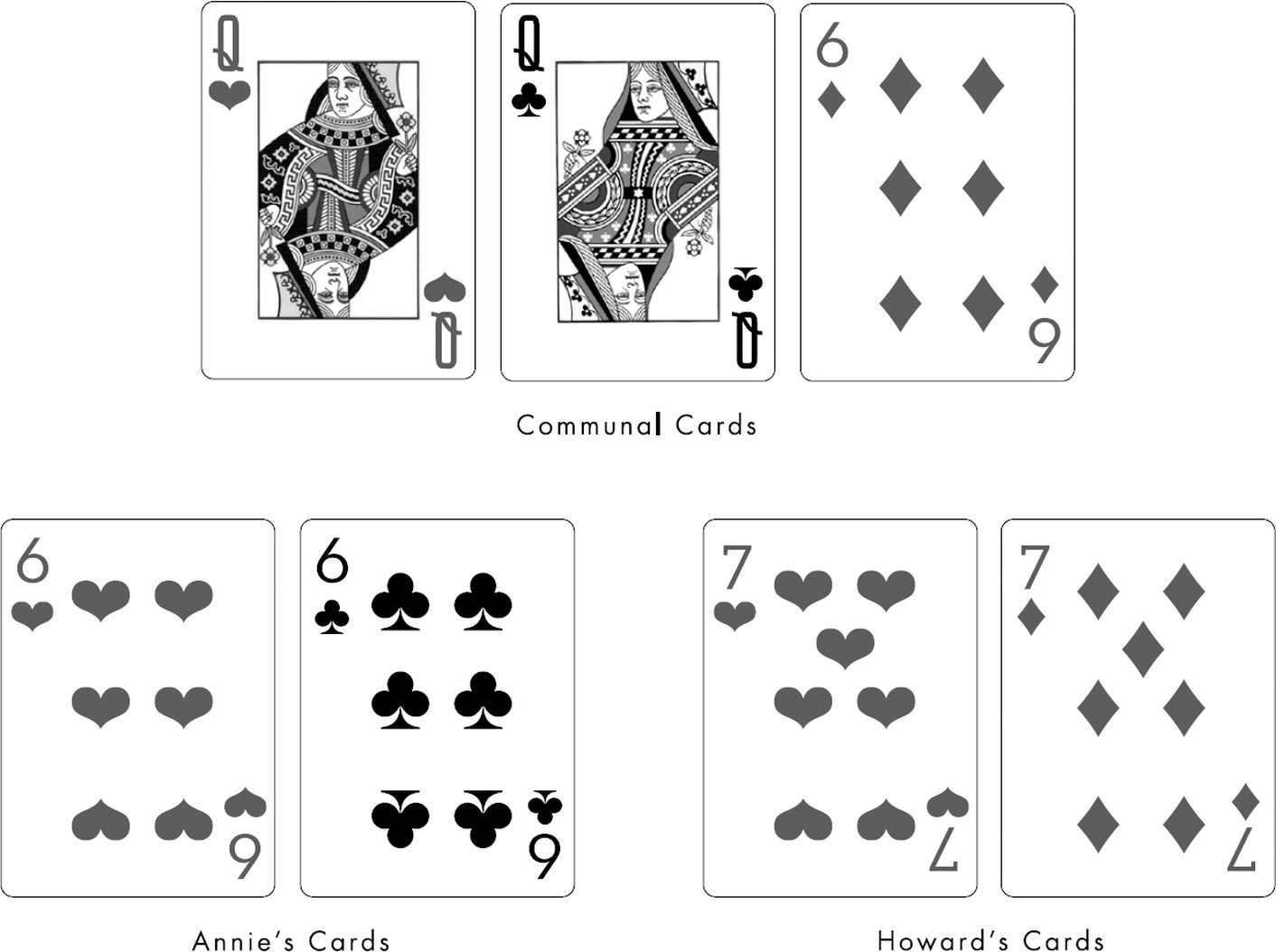

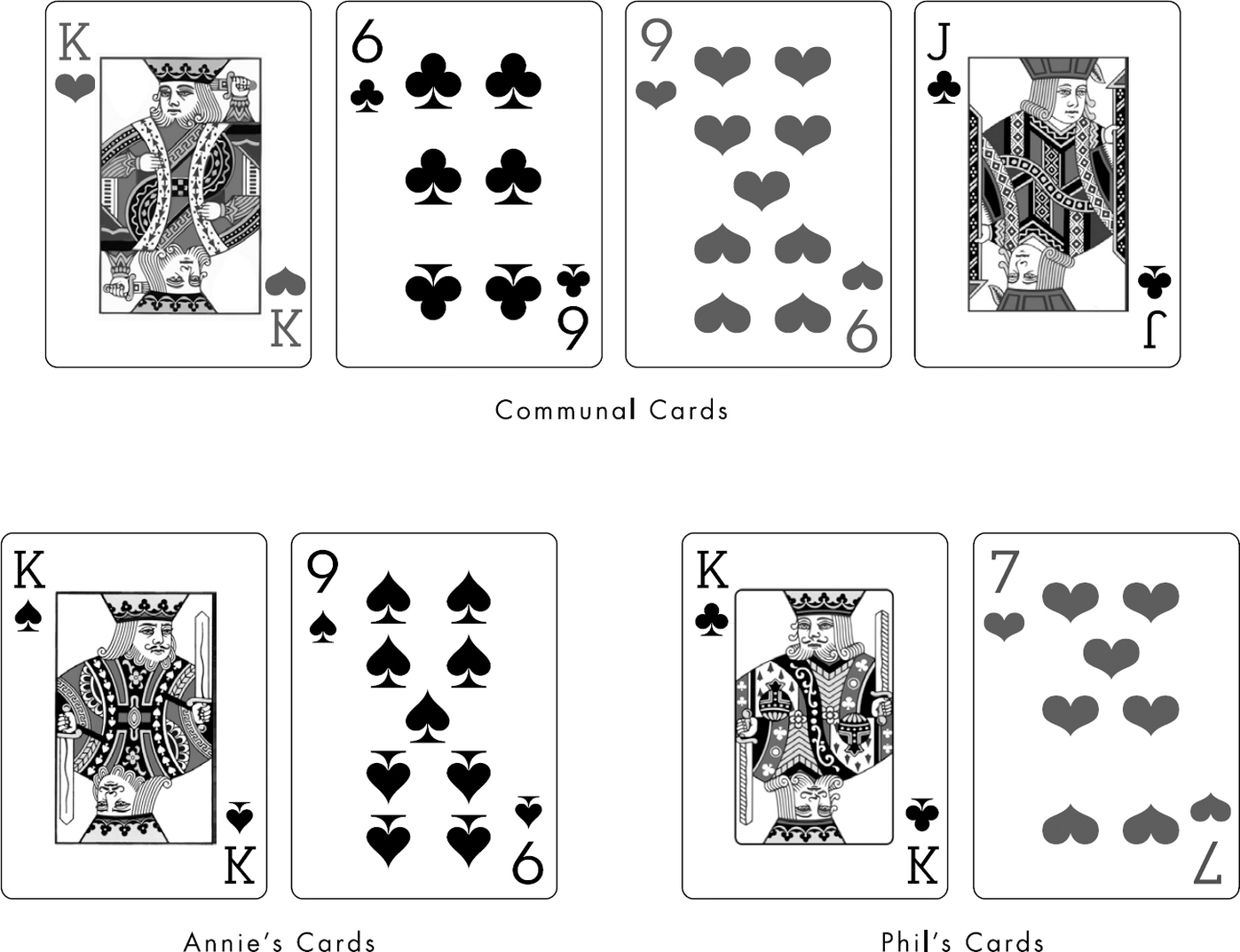

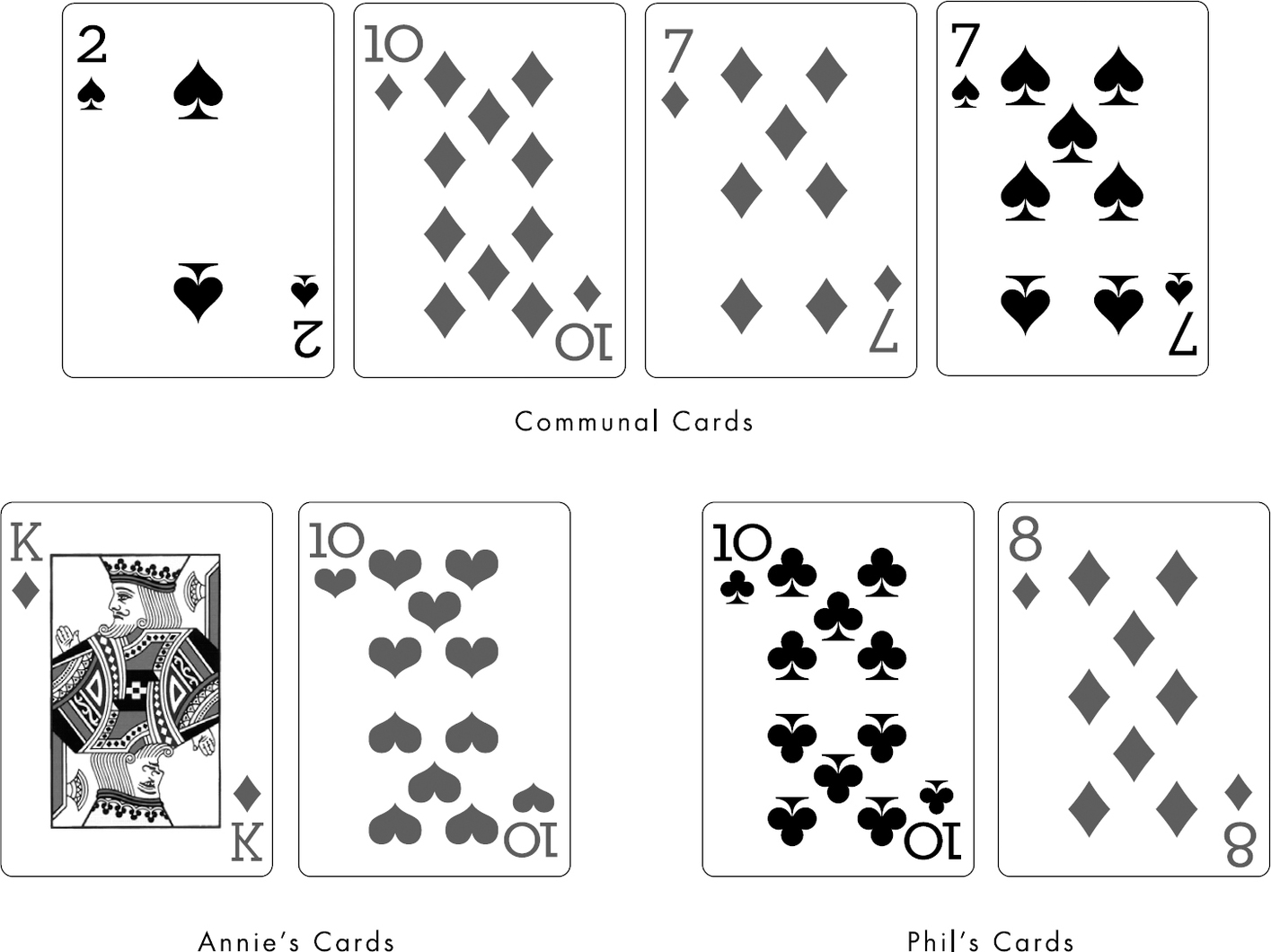

In Texas Hold’Em, the kind of poker Annie was playing, each player received two private cards, and then five communal cards were dealt, faceup, onto the middle of the table to be shared by everyone. The winner was whoever had the best combination of private and communal cards.

When Howard was learning to play, he told Annie, he would go to a late-night game with Wall Street traders, world-champion bridge players, and other assorted math nerds. Tens of thousands of dollars would trade hands as they played until dawn, and then everyone would get breakfast together and deconstruct the games. Howard eventually realized that the hard part of poker wasn’t the math. With enough practice, anyone can memorize odds or learn to estimate the chances of winning a pot. No, the hard part was learning to make choices based on probabilities.

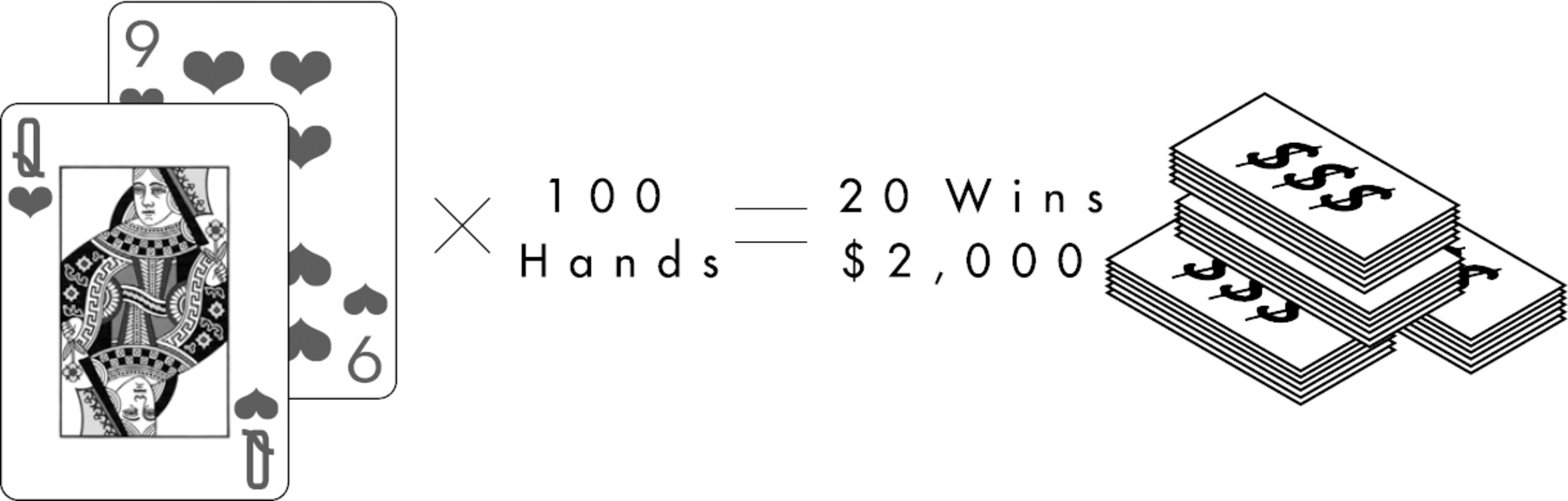

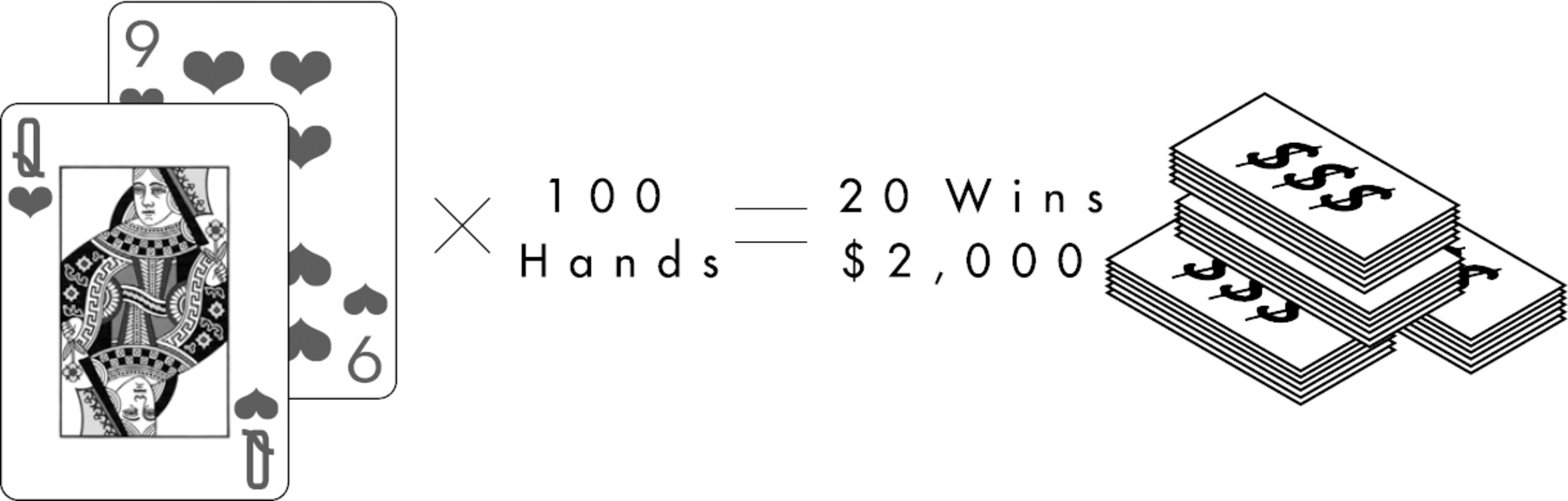

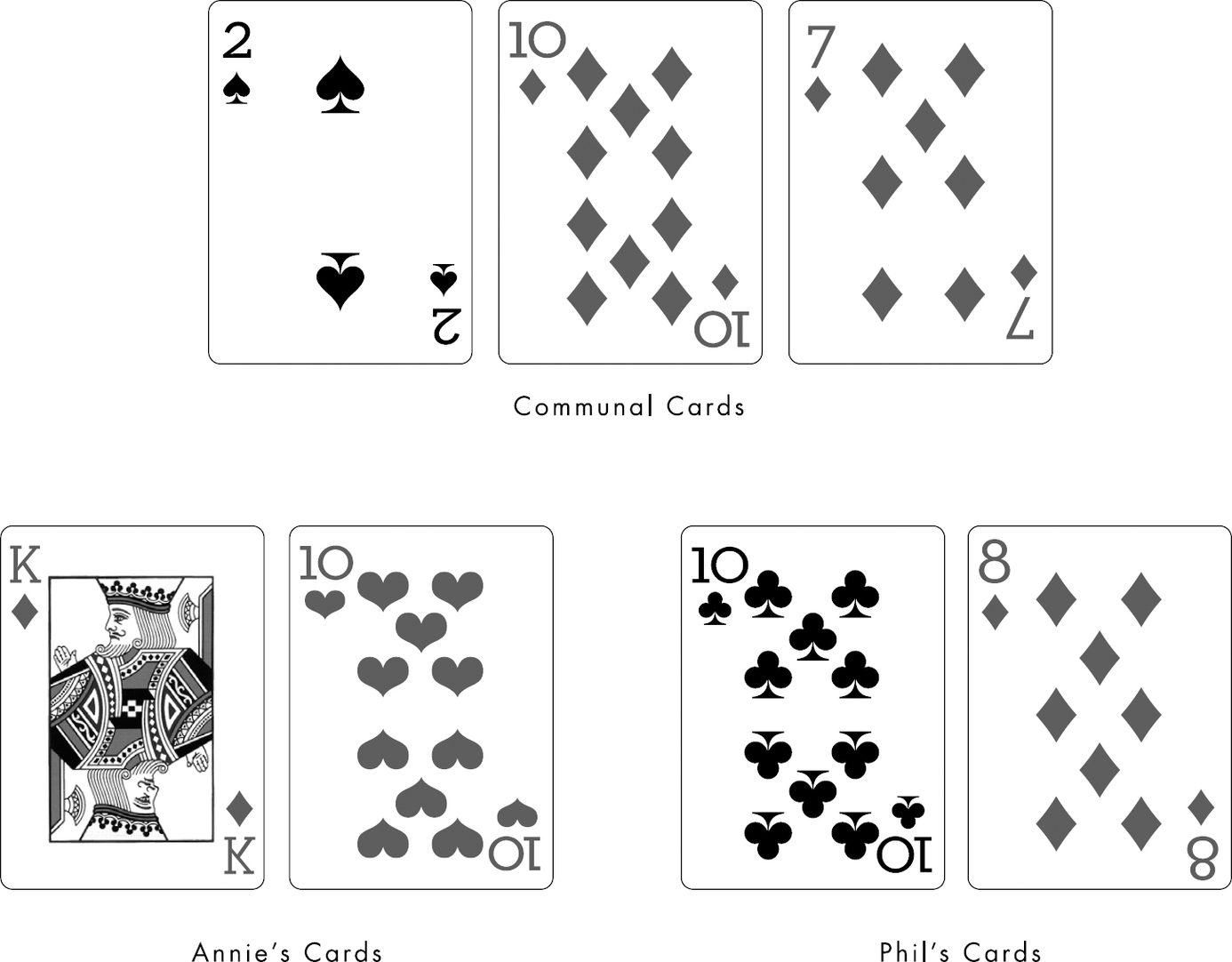

For example, let’s say you’re playing Texas Hold’Em, and you have a queen and nine of hearts as your private cards, and the dealer has put four communal cards on the table:

One more communal card is going to be dealt. If that last card is a heart, you have a flush, or five hearts, which is a strong hand. A quick mental calculation tells you that since there are 52 cards in a deck, and 4 hearts are already showing, there are 9 possible hearts remaining that might be dealt onto the table, as well as 37 nonheart cards. Put differently, there are 9 cards that will get you a flush, and 37 that won’t. The odds, then, of getting a flush are 9 to 37, or roughly 20 percent.*1

In other words, there’s an 80 percent chance you won’t make the flush and could lose your money. A novice player, based on those odds, will often fold and get out of the hand. That’s because a novice is focused on certainties: The odds of getting a flush are relatively small. Rather than throw money away on an unlikely outcome, they’ll quit.

But an expert sees this hand differently. “A good poker player doesn’t care about certainty,” Annie’s brother told her. “They care about knowing what they know and don’t know.”

For instance, if an expert is holding a queen and nine of hearts and hoping for a flush, and she sees her opponent bet $10, bringing the total pot to $100, a second set of probabilities starts getting calculated. To stay in the game—and see if the last card is a heart—the expert needs only to match the last wager, $10. If the expert bets $10 and makes the flush, she’ll win $100. The expert is being offered “pot odds” of 10 to 1, because if she wins, she’ll get $10 for every $1 she bets right now.

Now the expert player can compare those odds by imagining this hand one hundred times. The expert doesn’t know if she is going to win or lose this hand, but she does know that if she played this exact same hand one hundred times, she would, on average, win twenty times, collecting $100 with each victory, yielding $2,000.

And she knows that playing one hundred times will cost her only an additional $1,000 (because she has to bet only $10 each time). So even if she lost eighty times and won only twenty times, she would still pocket an extra $1,000 (which is the winnings of $2,000 less the $1,000 needed to play).

Got it? It’s okay if you don’t, because the point here is that probabilistic thinking tells the expert how to proceed: She is aware there’s a lot she can’t predict. But if she played this same hand one hundred times, she would probably end up $1,000 richer. So the expert makes the bet and stays in the game. She knows, from a probabilistic standpoint, it will pay off over time. It doesn’t matter that this hand is uncertain. What matters is committing to odds that pay off in the long run.

“Most players are obsessed with finding the certainty on the table, and it colors their choices,” Annie’s brother told her. “Being a great player means embracing uncertainty. As long as you’re okay with uncertainty, you can make the odds work for you.”

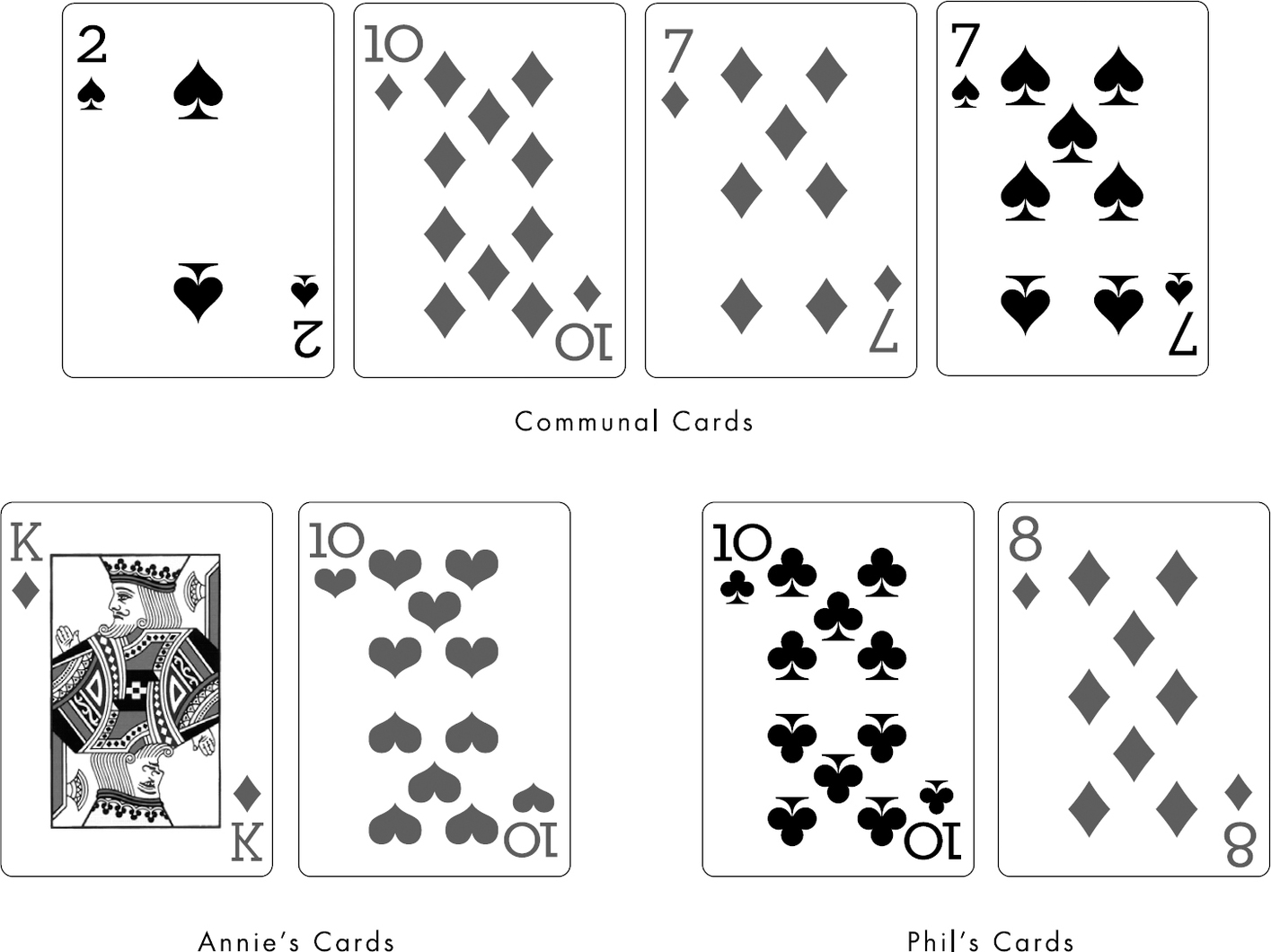

Annie’s brother, Howard, is competing in this Tournament of Champions right alongside her when the FossilMan is eliminated. Over the past two decades, Howard has established himself as one of the finest players in the world. He has two World Series of Poker bracelets and millions in winnings. Early in the tournament, Annie and Howard lucked out and didn’t have to directly compete for many big pots. Now, however, seven hours have passed.

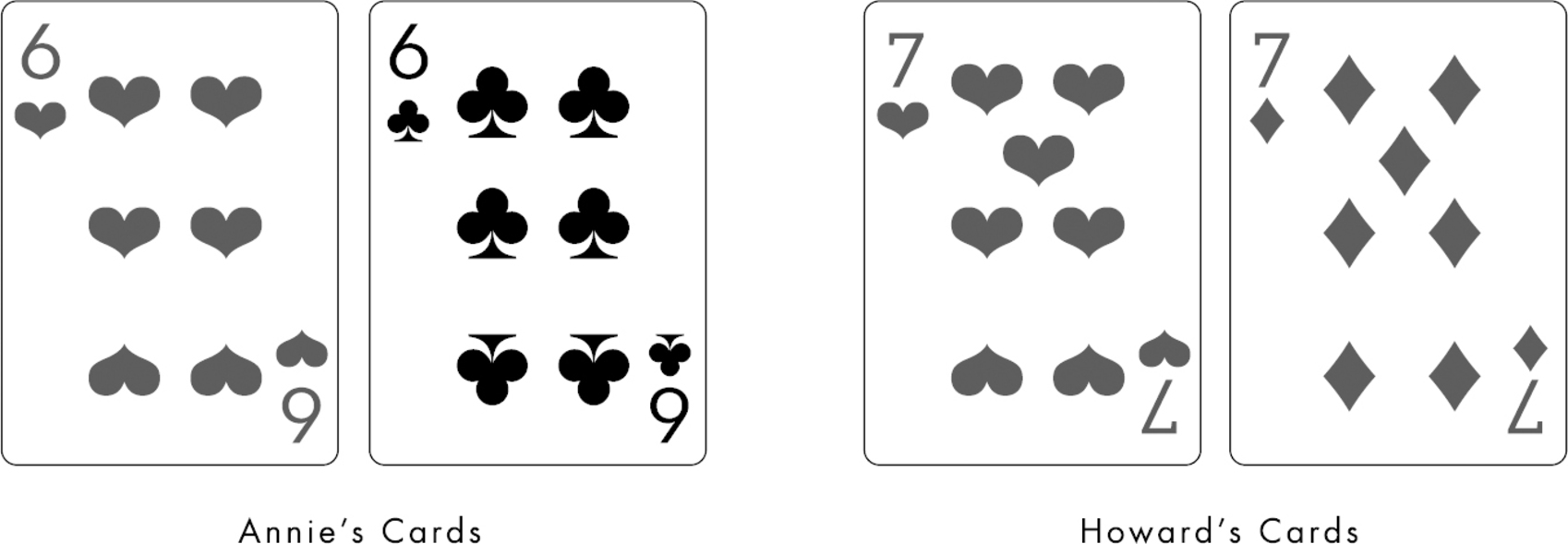

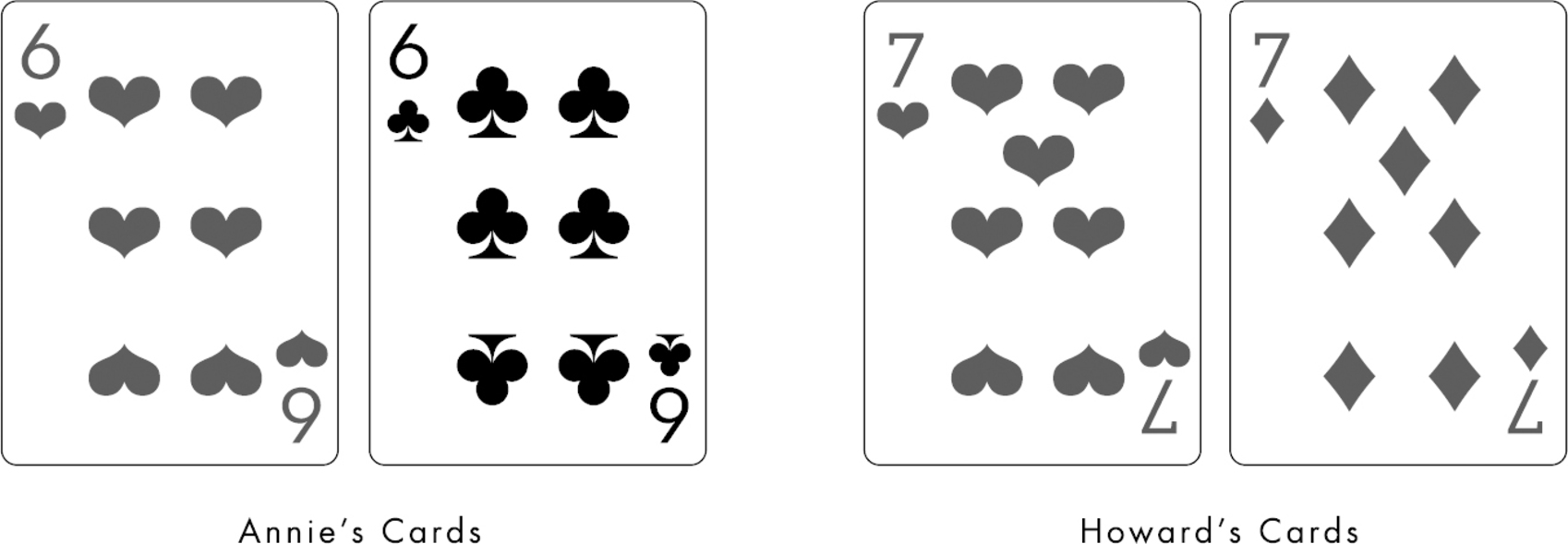

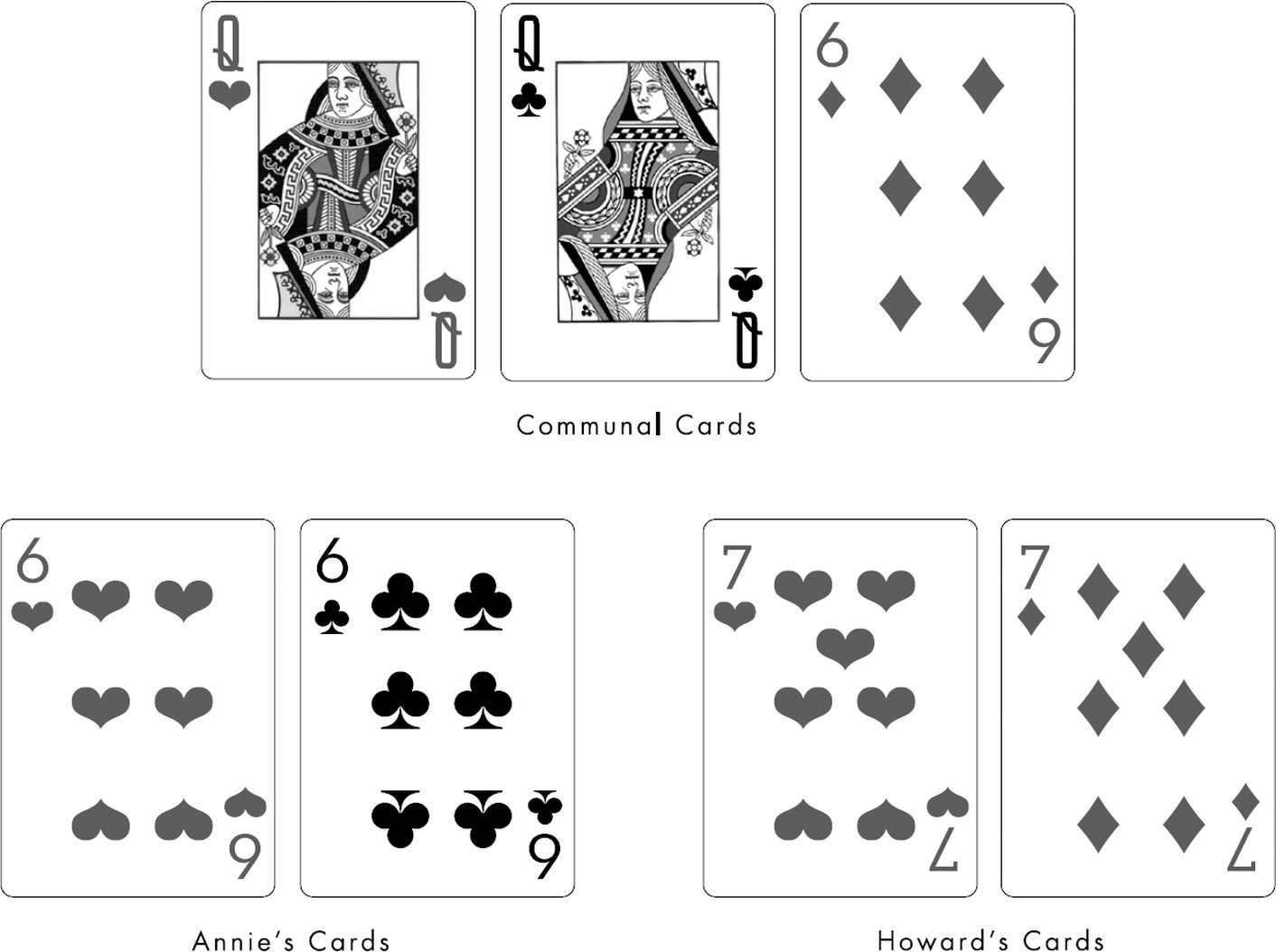

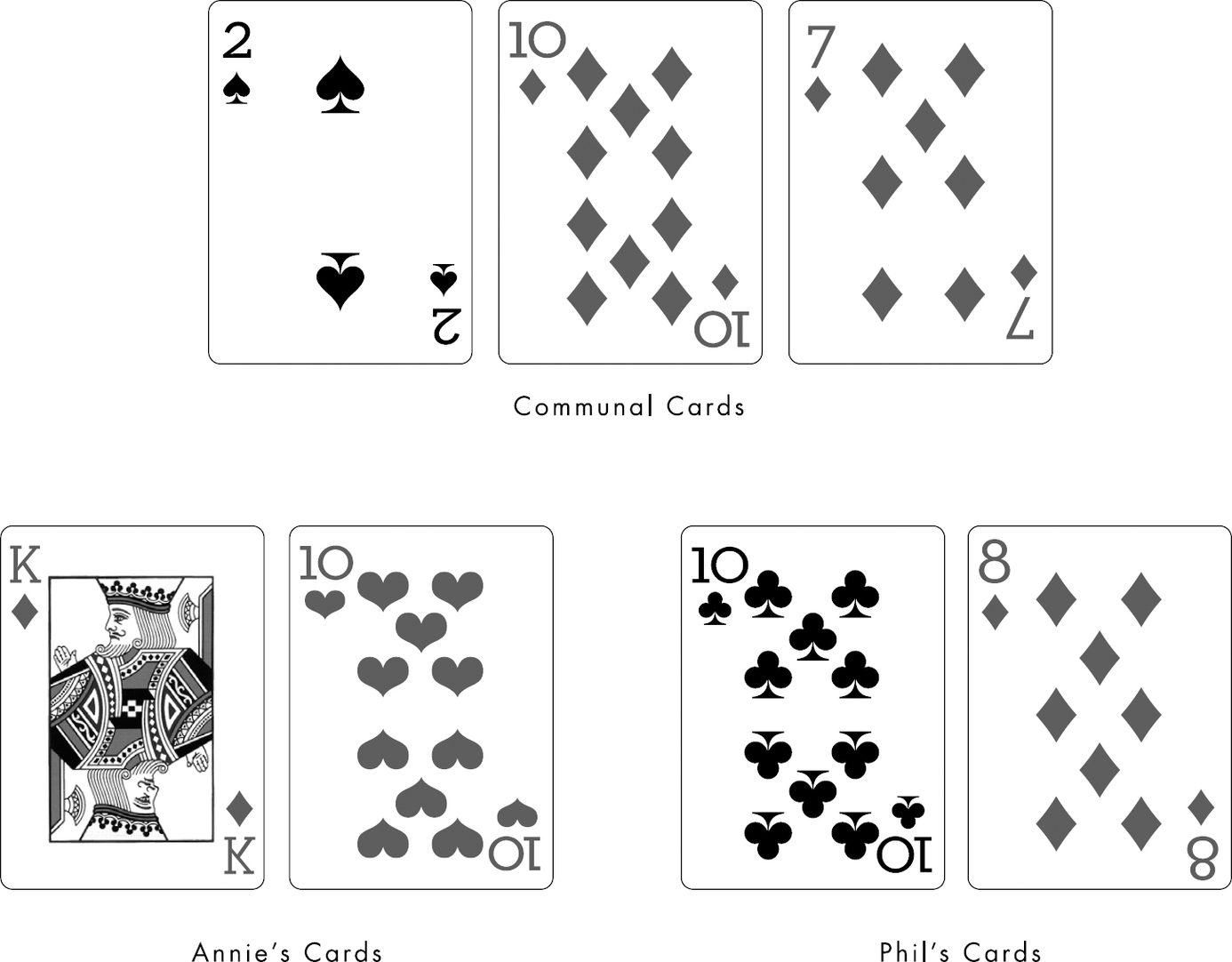

First the FossilMan was eliminated by that bit of bad luck. Another competitor named Doyle Brunson, a seventy-one-year-old nine-time champion, was knocked out by a risky attempt to double his chips. Phil Ivey, who won his first World Series of Poker tournament at twenty-four, was eliminated by Annie when she drew an ace and queen against Ivey’s ace and eight. Over time, the players at the table have dwindled until there are only three players remaining: Annie, Howard, and a man named Phil Hellmuth. It is inevitable Annie and Howard will butt up against each other. The contestants spar over chips and hands for ninety minutes. Then Annie gets a pair of sixes.

She starts tallying what she does and doesn’t know. She knows she has strong cards. She knows, from a probabilistic standpoint, that if she played this hand one hundred times, she would do okay. “Sometimes when I’m teaching poker, I’ll tell people there are situations where you shouldn’t even look at your cards before you bet,” Annie told me. “Because if the pot odds are in your favor, you should always make the bet. Just commit to it.”

Howard, her brother, seems to like his hand as well, because he pushes all of his chips, $310,000, onto the table. Phil Hellmuth folds. The bet is to Annie.

“I’ll call,” she says.

They both turn over their cards. Annie reveals her pair of sixes.

Howard reveals a pair of sevens.

“Nice hand, Bub,” Annie says. Howard has an 82 percent chance of winning this hand, collecting chips worth more than half a million dollars, and becoming the table’s dominant leader. From a probabilistic perspective, they both played this hand exactly right. “Annie made the right choice,” Howard later said. “She committed to the odds.”

The dealer turns over the first three communal cards.

“Oh, God,” Annie says and covers her face. “Oh, God.”

The six and the two queens in the communal pile give Annie a full house. If Annie and Howard replayed this hand one hundred times, Howard would likely win eighty-two of those contests. But not this time. The dealer puts the remaining cards on the table.

Howard is out.

Annie jumps from her chair and hugs her brother. “I’m sorry, Howard,” she whispers. Then she runs out of the studio. She starts sobbing before she makes it to the door.

“It’s okay,” Howard says when he finds her in the hall. “Just beat Phil now.”

“You have to learn to live with it,” Howard told me later. “I just went through this same thing with my son. He was applying to colleges and he was nervous about it, so we came up with a list of twelve schools—four safety schools, four he had an even chance of getting into, and four that were stretches—and we sat down and started calculating the odds.”

By looking at the statistics those schools had published online, Howard and his son calculated the likelihood of getting into each college. Then they added all those probabilities together. It was fairly basic math, the kind even English majors can manage with a little bit of Googling. They figured out that Howard’s son had a 99.5 percent chance of getting into at least one school, and a better than even chance of getting into a good school. But it was far from certain he would get into one of the stretch schools, the ones he had fallen in love with. “That was disappointing, but by going through the numbers, he felt less anxious,” Howard said. “It prepared him for the possibility that he wouldn’t get into his first choice, but he would definitely get in somewhere.

“Probabilities are the closest thing to fortune-telling,” Howard said. “But you have to be strong enough to live with what they tell you might occur.”

III.

In the late 1990s, a professor of cognitive science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology named Joshua Tenenbaum began a large-scale examination of the casual ways that people make everyday predictions. There are dozens of questions each of us confront on a daily basis that can be answered only with some amount of forecasting. When we estimate how long a meeting will last, for instance, or envision two driving routes and guess at which one will have less traffic, or predict whether our families will have more fun at the beach or at Disneyland, we’re making forecasts that assign likelihoods to various outcomes. We may not realize it, but we’re thinking probabilistically. How, Tenenbaum wondered, do our brains do that?

Tenenbaum’s specialty was computational cognition—in particular, the similarities in how computers and humans process information. A computer is an inherently deterministic machine. It can predict if your family will prefer the beach or Disneyland only if you give it a specific formula for comparing the merits of beach fun versus amusement parks. Humans, on the other hand, can make such decisions even if we’ve never visited the seaside or Magic Kingdom before. Our brains can infer from past experiences that, because the kids always complain when we go camping and love watching cartoons, everyone will probably have more fun with Mickey and Goofy.

“How do our minds get so much from so little?” Tenenbaum wrote in a paper published in the journal Science in 2011. “Any parent knows, and scientists have confirmed, that typical 2-year-olds can learn how to use a new word such as ‘horse’ or ‘hairbrush’ from seeing just a few examples.” To a two-year-old, horses and hairbrushes have a great deal in common. The words sound similar. In pictures, they both have long bodies with a series of straight lines—in one case legs, in the other bristles—extruding outward. They come in a range of colors. And yet, though a child might have seen only one picture of a horse and used only one hairbrush, she can quickly learn the difference between those words.

A computer, on the other hand, needs explicit instructions to learn when to use “horse” versus “hairbrush.” It needs software that specifies that four legs increases the odds of horsiness, while one hundred bristles increases the probability of a hairbrush. A child can make such calculations before she can form sentences. “Viewed as a computation on sensory input data, this is a remarkable feat,” Tenenbaum wrote. “How does a child grasp the boundaries of these subsets from seeing just one or a few examples of each?”

In other words, why are we so good at forecasting certain kinds of things—and thus, making decisions—when we have so little exposure to all the possible odds?

In an attempt to answer this question, Tenenbaum and a colleague, Thomas Griffiths, devised an experiment. They scoured the Internet for data on different kinds of predictable events, such as how much money a movie will make at the box office, or how long the average person lives, or how long a cake needs to bake. They were interested in these events because if you were to graph multiple examples of each one, a distinct pattern would emerge. Box office totals, for instance, typically conform to a basic rule: There are a few blockbusters each year that make a huge amount of money, and lots of other films that never break even.

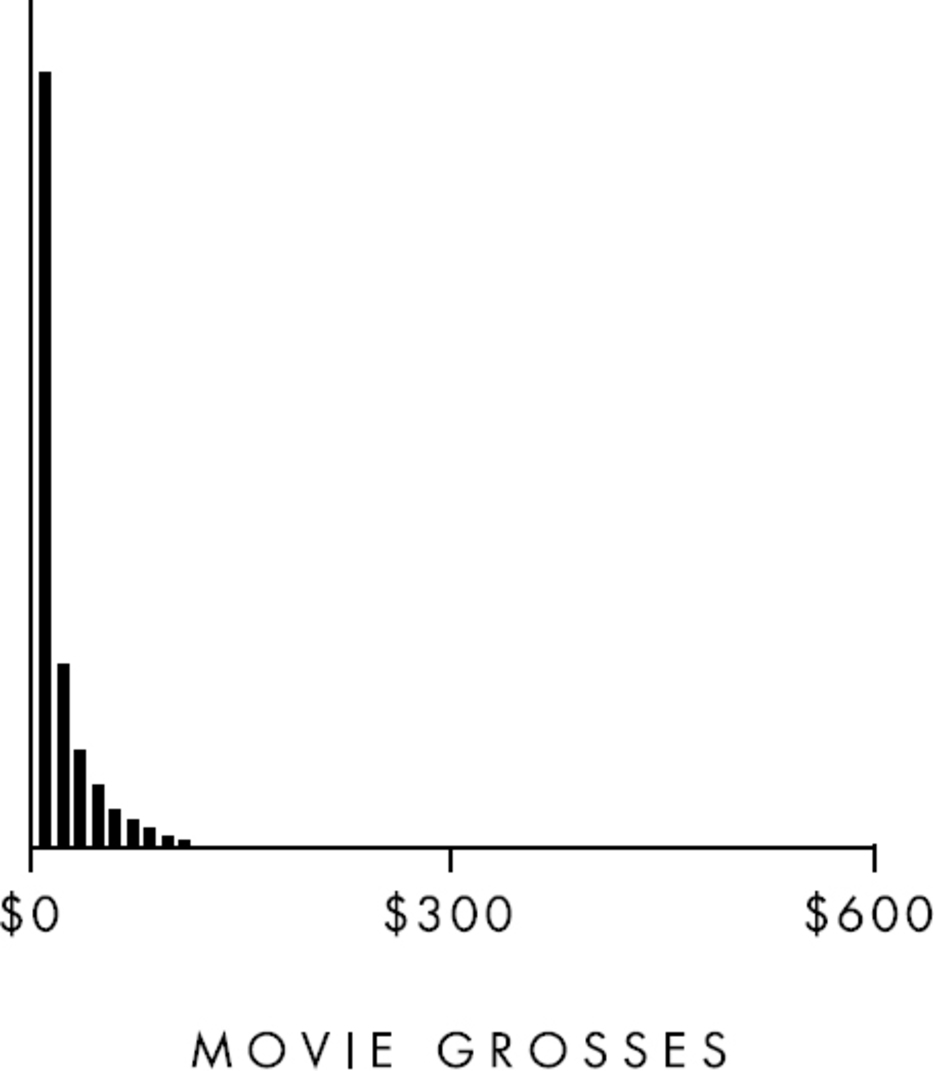

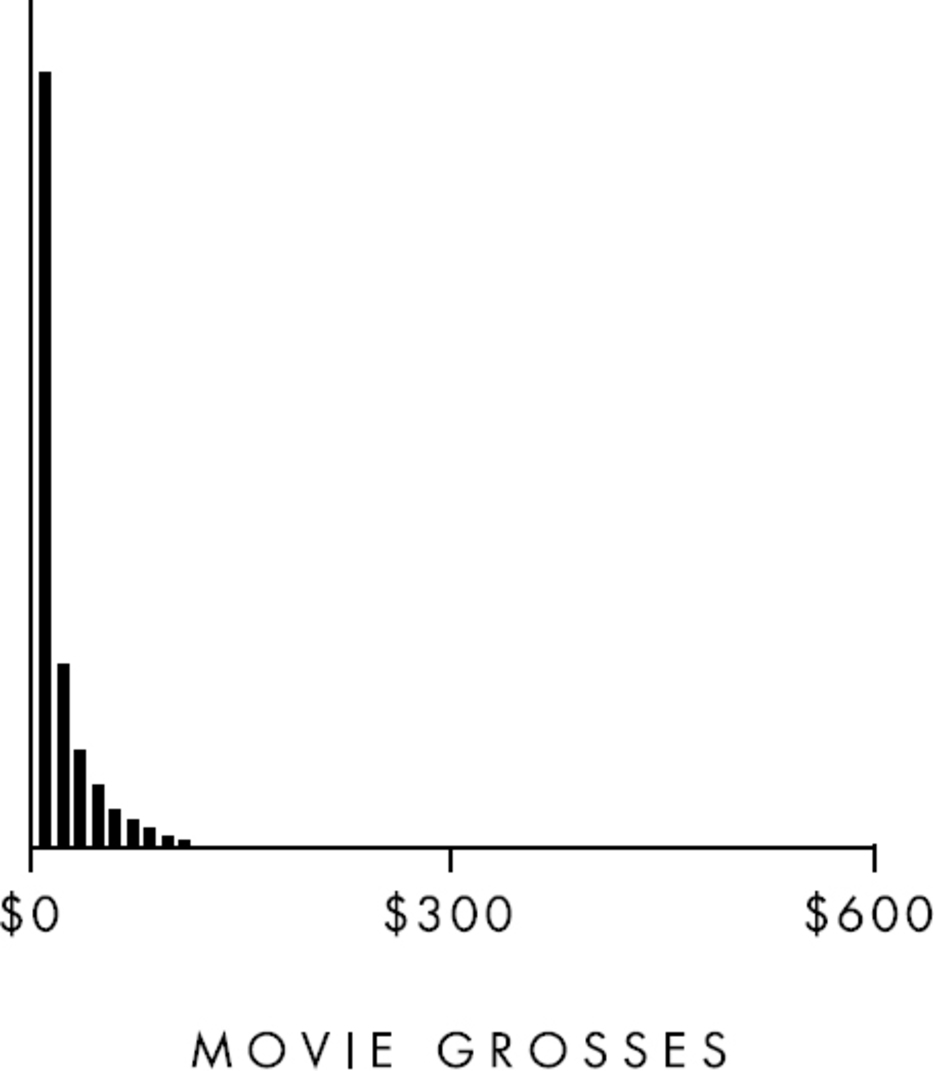

Within mathematics, this is known as a “power law distribution,” and when the revenues of all the movies released in a given year are graphed together, it looks like this:

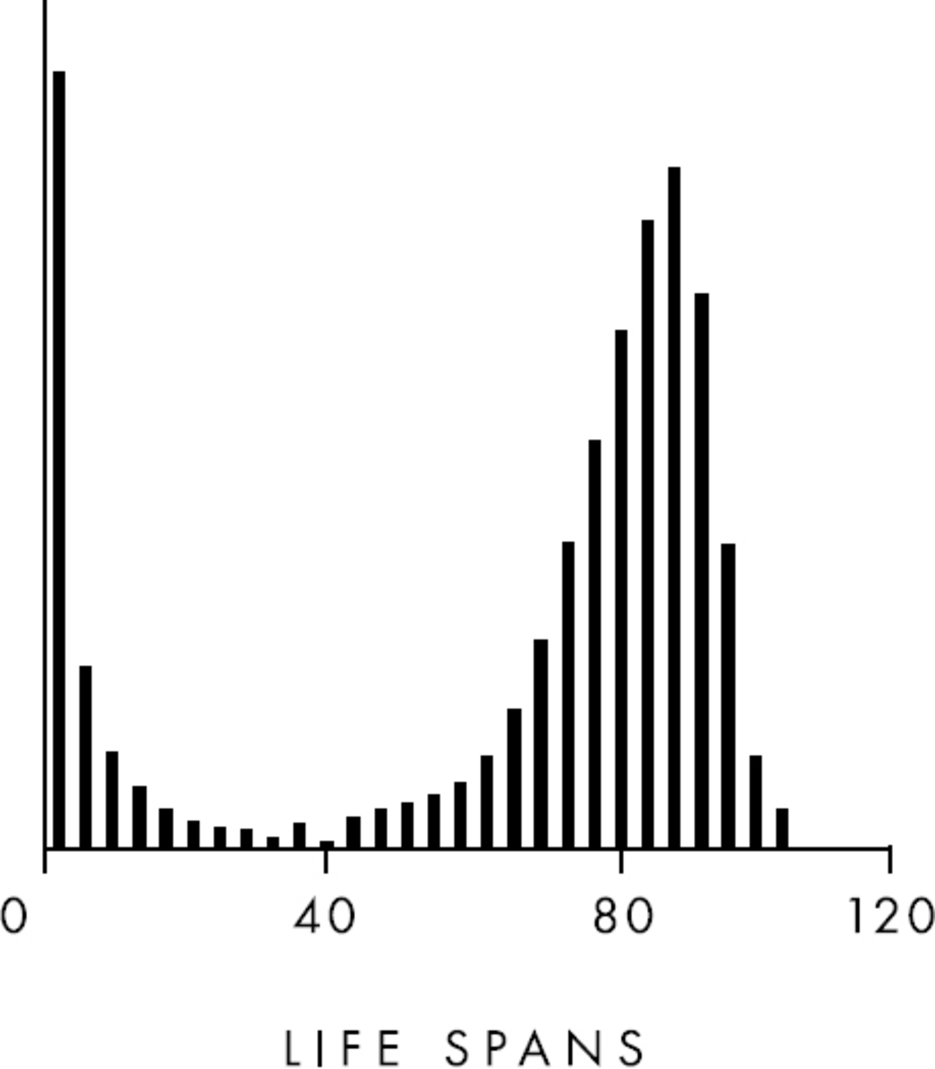

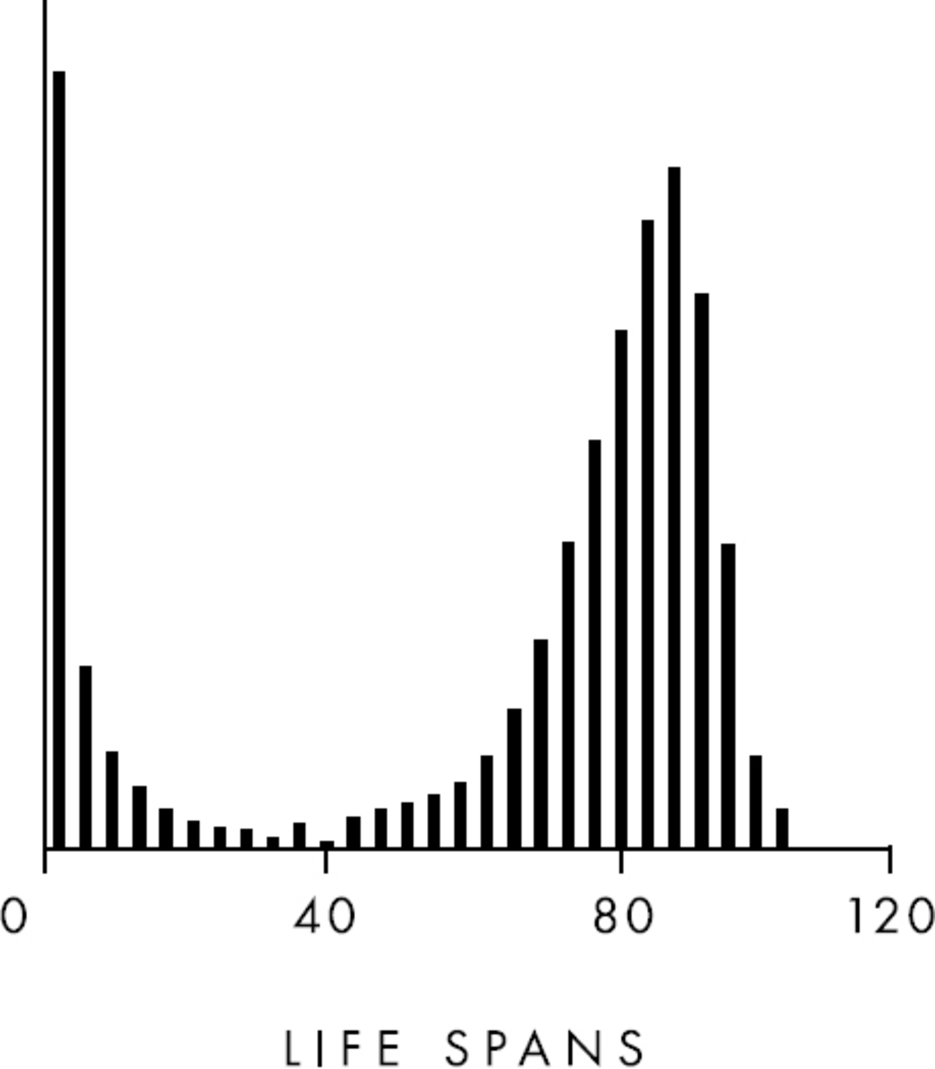

Graphing other kinds of events results in different patterns. Take life spans. A person’s odds of dying in a specific year spike slightly at birth—because some infants perish soon after they arrive—but if a baby survives its first few years, it is likely to live decades longer. Then, starting at about age forty, our odds of dying start accelerating. By fifty, the likelihood of death jumps each year until it peaks at about eighty-two.

Life spans adhere to a normal, or Gaussian, distribution curve. That pattern looks like this:

Most people intuitively understand that they need to apply different kinds of reasoning to predicting different kinds of events. We know that box office totals and life spans require different types of estimations, even if we don’t know anything about medical statistics or entertainment industry trends. Tenenbaum and Griffiths were curious to find out how people intuitively learn to make such estimations. So they found events with distinct patterns, from box office grosses to life spans, as well as the average length of poems, the careers of congressmen (which adhere to an Erlang distribution), and the length of time a cake needs to bake (which has no strong pattern).

Then they asked hundreds of students to predict the future based on one piece of data:

You read about a movie that has made $60 million to date. How much will it make in total?

You meet someone who is thirty-nine years old. How long will he or she live?

A cake has been baking for fourteen minutes. How much longer does it need to stay in the oven?

You meet a U.S. congressman who has served for fifteen years. How long will he serve in total?

The students weren’t given any additional information. They weren’t told anything about power law distributions or Erlang curves. Rather, they were simply asked to make a prediction based on one piece of data and no guidance about what kinds of probabilities to apply.

Despite those handicaps, the students’ predictions were startlingly accurate. They knew that a movie that’s earned $60 million is a blockbuster, and is likely to take in another $30 million in ticket sales. They intuited that if you meet someone in their thirties, they’ll probably live another fifty years. They guessed that if you meet a congressman who has been in power for fifteen years, he’ll probably serve another seven or so, because incumbency brings advantages, but even powerful lawmakers can be undone by political trends.

If asked, few of the participants were able to describe the mental logic they used to make their forecasts. They just gave answers that felt right. On average, their predictions were often within 10 percent of what the data said was the correct answer. In fact, when Tenenbaum and Griffiths graphed all of the students’ predictions for each question, the resulting distribution curves almost perfectly matched the real patterns the professors had found in the data they had collected online.

Just as important, each student intuitively understood that different kinds of predictions required different kinds of reasoning. They understood, without necessarily knowing why, that life spans fit into a normal distribution curve whereas box office grosses tend to conform to a power law.

Some researchers call this ability to intuit patterns “Bayesian cognition” or “Bayesian psychology,” because for a computer to make those kinds of predictions, it must use a variation of Bayes’ rule, a mathematical formula that generally requires running thousands of models simultaneously and comparing millions of results.*2 At the core of Bayes’ rule is a principle: Even if we have very little data, we can still forecast the future by making assumptions and then skewing them based on what we observe about the world. For instance, suppose your brother said he’s meeting a friend for dinner. You might forecast there’s a 60 percent chance he’s going to meet a man, since most of your brother’s friends are male. Now, suppose your brother mentioned his dinner companion was a friend from work. You might want to change your forecast, since you know that most of his coworkers are female. Bayes’ rule can calculate the precise odds that your brother’s dinner date is female or male based on just one or two pieces of data and your assumptions. As more information comes in—his companion’s name is Pat, he or she loves adventure movies and fashion magazines—Bayes’ rule will refine the probabilities even more.

Humans can make these kinds of calculations without having to think about them very hard, and we tend to be surprisingly accurate. Most of us have never studied actuarial tables of life spans, but we know, based on experience, that it is relatively uncommon for toddlers to die and more typical for ninety-year-olds to pass away. Most of us don’t pay attention to box office statistics. But we are aware that there are a few movies each year that everyone sees, and a bunch of films that disappear from the theaters within a week or two. So we make assumptions about life spans and box office revenues based on our experiences, and our instincts become increasingly nuanced the more funerals or movies we attend. Humans are astoundingly good Bayesian predictors, even if we’re unaware of it.

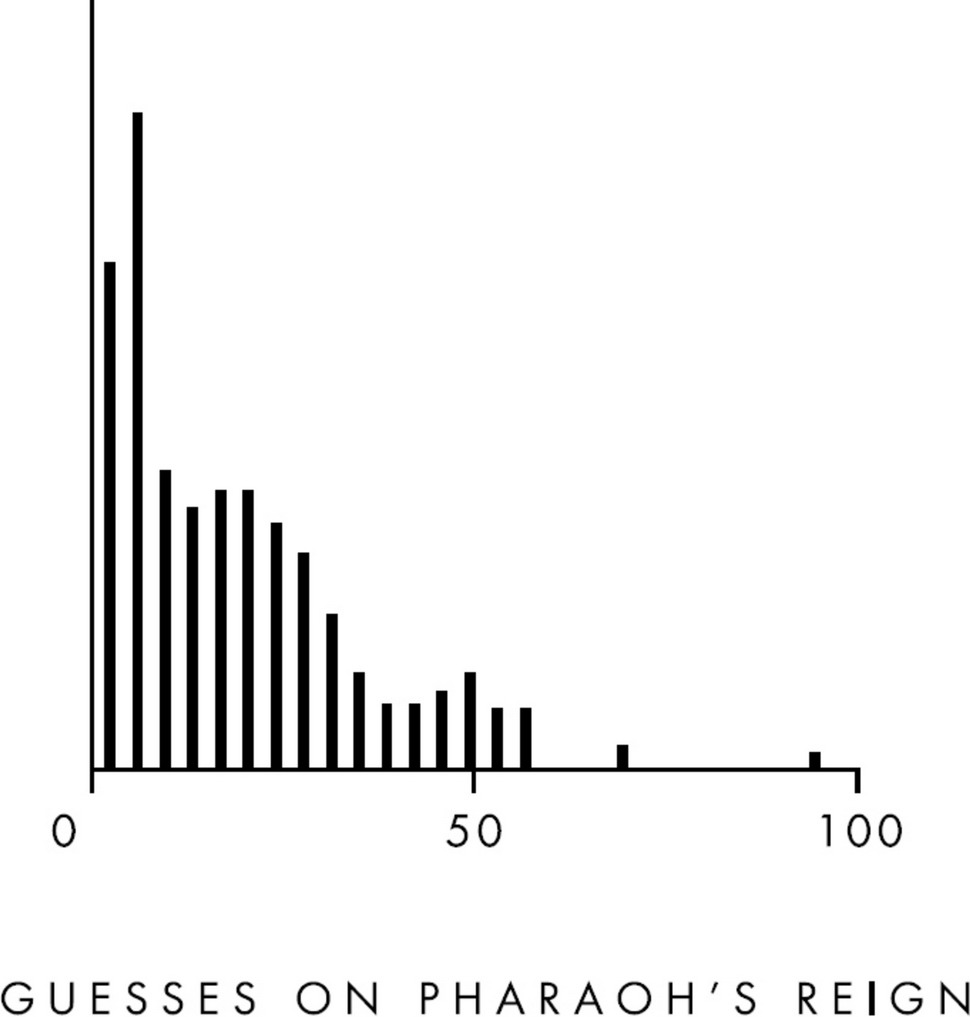

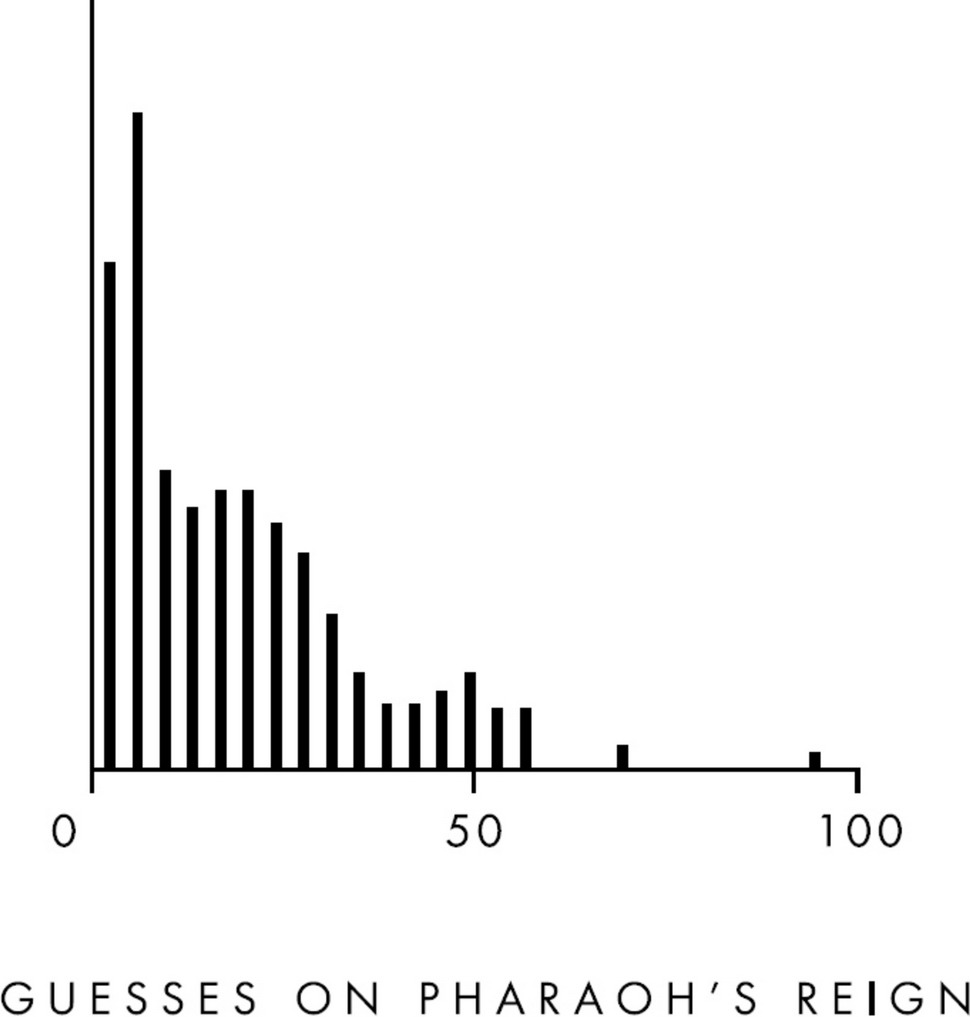

Sometimes, however, we make mistakes. For instance, when Tenenbaum and Griffiths asked their students to predict how long an Egyptian pharaoh would reign if he has already ruled for eleven years, a majority of them assumed that pharaohs are similar to other kinds of royalty, such as European kings. Most people know, from reading history books and watching television, that some royalty die early in life. But, in general, if a king or queen survives to middle age, they usually stay on the throne until their hair is gray. So it seemed logical, to Tenenbaum’s participants, that pharaohs would be similar. They offered a range of guesses with an average of about twenty-three additional years in power:

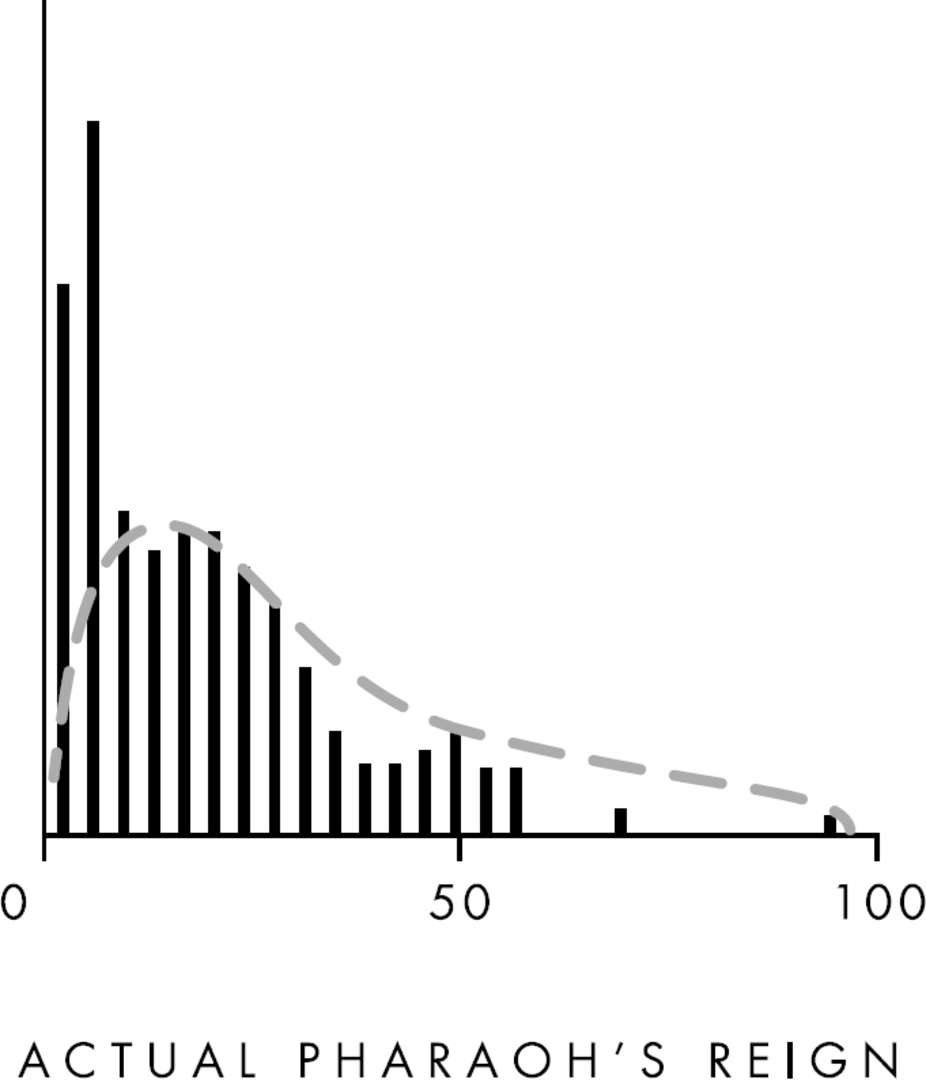

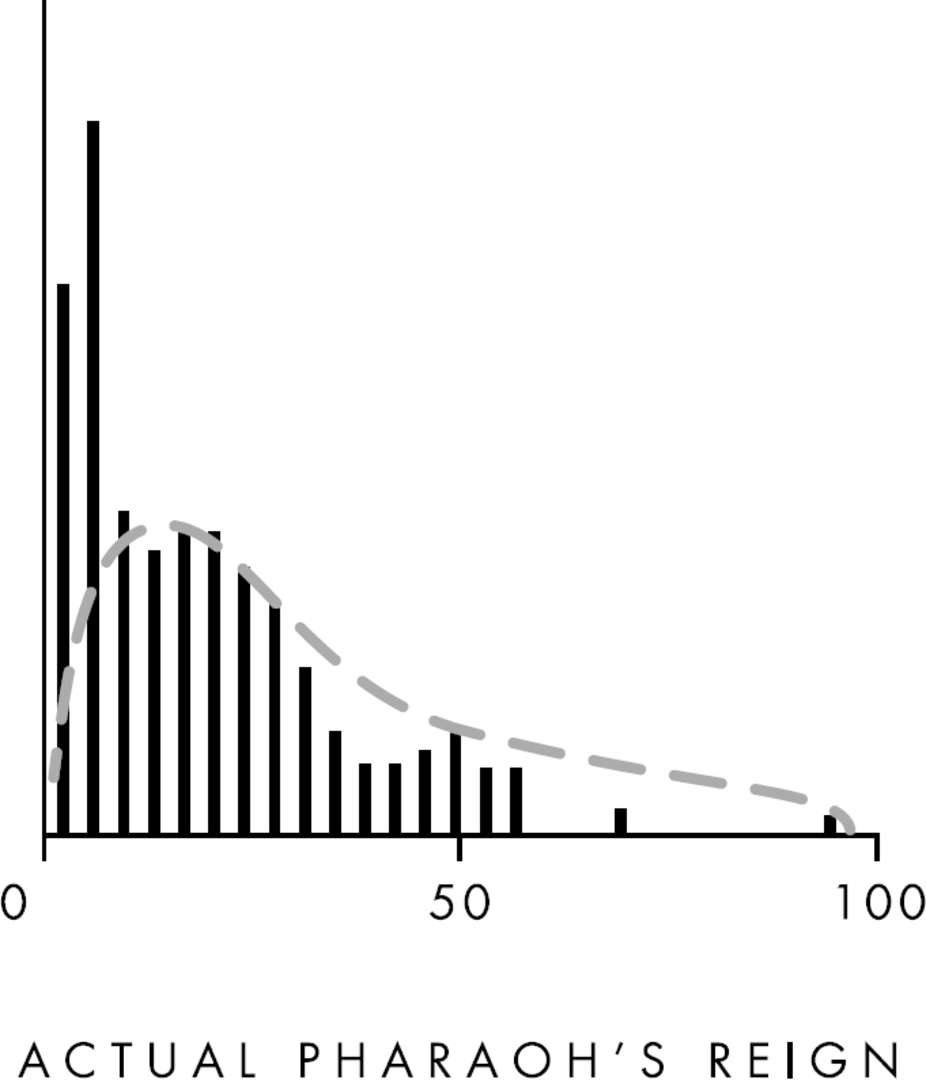

That would be a great guess for a British king. But it’s a bad guess for an Egyptian pharaoh, because four thousand years ago people had much shorter life spans. Most pharaohs were considered elderly if they made it to thirty-five. So the correct answer is that a pharaoh with eleven years on the throne is expected to reign only another twelve years and then die of disease or some other common cause of death in ancient Egypt:

The students got the reasoning right. They intuited correctly that calculating a pharaoh’s reign follows an Erlang distribution. But their assumption—what Bayesians call the “prior” or “base rate”—was off. And because they had a bad assumption about how long ancient Egyptians lived, their subsequent predictions were skewed, as well.

“It’s incredible that we’re so good at making predictions with such little information and then adjusting them as we absorb data from life,” Tenenbaum told me. “But it only works if you start with the right assumptions.”

So how do we get the right assumptions? By making sure we are exposed to a full spectrum of experiences. Our assumptions are based on what we’ve encountered in life, but our experiences often draw on biased samples. In particular, we are much more likely to pay attention to or remember successes and forget about failures. Many of us learn about the business world, for instance, by reading newspapers and magazines. We most frequently go to busy restaurants and see the most popular movies. The problem is that such experiences disproportionately expose us to success. Newspapers and magazines tend to devote more coverage to start-ups that were acquired for $1 billion, and less to the hundreds of similar companies that went bankrupt. We hardly notice the empty restaurants we pass on the way to our favorite, crowded pizza place. We become trained, in other words, to notice success and then, as a result, we predict successful outcomes too often because we’re relying on experiences and assumptions that are biased toward all the successes we’ve seen—rather than the failures we’ve overlooked.

Many successful people, in contrast, spend an enormous amount of time seeking out information on failures. They read inside the newspaper’s business pages for articles on companies that have gone broke. They schedule lunches with colleagues who haven’t gotten promoted, and then ask them what went wrong. They request criticisms alongside praise at annual reviews. They scrutinize their credit card statements to figure out why, precisely, they haven’t saved as much as they hoped. They pick over their daily missteps when they get home, rather than allowing themselves to forget all the small errors. They ask themselves why a particular call didn’t go as well as they had hoped, or if they could have spoken more succinctly at a meeting. We all have a natural proclivity to be optimistic, to ignore our mistakes and forget others’ tiny errors. But making good predictions relies on realistic assumptions, and those are based on our experiences. If we pay attention only to good news, we’re handicapping ourselves.

“The best entrepreneurs are acutely conscious of the risks that come from only talking to people who have succeeded,” said Don Moore, the Berkeley professor who participated in the GJP and who also studies the psychology of entrepreneurship. “They are obsessed with spending time around people who complain about their failures, the kinds of people the rest of us usually try to avoid.”

This, ultimately, is one of the most important secrets to learning how to make better decisions. Making good choices relies on forecasting the future. Accurate forecasting requires exposing ourselves to as many successes and disappointments as possible. We need to sit in crowded and empty theaters to know how movies will perform; we need to spend time around both babies and old people to accurately gauge life spans; and we need to talk to thriving and failing colleagues to develop good business instincts.

This is hard, because success is easier to stare at. People tend to avoid asking friends who were just fired rude questions; we’re hesitant to interrogate divorced colleagues about what precisely went wrong. But calibrating your base rate requires learning from both the accomplished and the humbled.

So the next time a friend misses out on a promotion, ask him why. The next time a deal falls through, call up the other side to find out what you did wrong. The next time you have a bad day or you snap at your spouse, don’t simply tell yourself that things will go better next time. Instead, force yourself to really figure out what happened.

Then use those insights to forecast more potential futures, to dream up more possibilities of what might occur. You’ll never know with 100 percent certainty how things will turn out. But the more you force yourself to envision potential futures, the more you learn about which assumptions are certain or flimsy, the better your odds of making a great decision next time.

Annie knows a lot about Bayesian thinking from graduate school, and she uses it in poker games. “When I play against someone I’ve never met before, the first thing I do is start thinking about base rates,” she told me. “To someone who has never studied Bayes’ rule, the way I play might seem like I’m prejudiced, because if I’m sitting across from, say, a forty-year-old businessman, I’m going to assume all he cares about is telling his friends he played against pros and he doesn’t really care about winning, so he’ll take lots of risks. Or, if I’m sitting across from a twenty-two-year-old in a poker T-shirt, I’m going to assume he learned to play online so he’s got a tight, limited game.

“But the difference between prejudice and Bayesian thinking is that I try to improve my assumptions as we go along. So once we start playing, if I see that the forty-year-old is a great bluffer, that might mean he’s a professional hoping everyone will underestimate him. Or, if the twenty-two-year-old is trying to bluff every hand, it probably means he’s some rich kid who doesn’t know what he’s doing. I spend a lot of time updating my assumptions because, if they’re wrong, my base rate is off.”

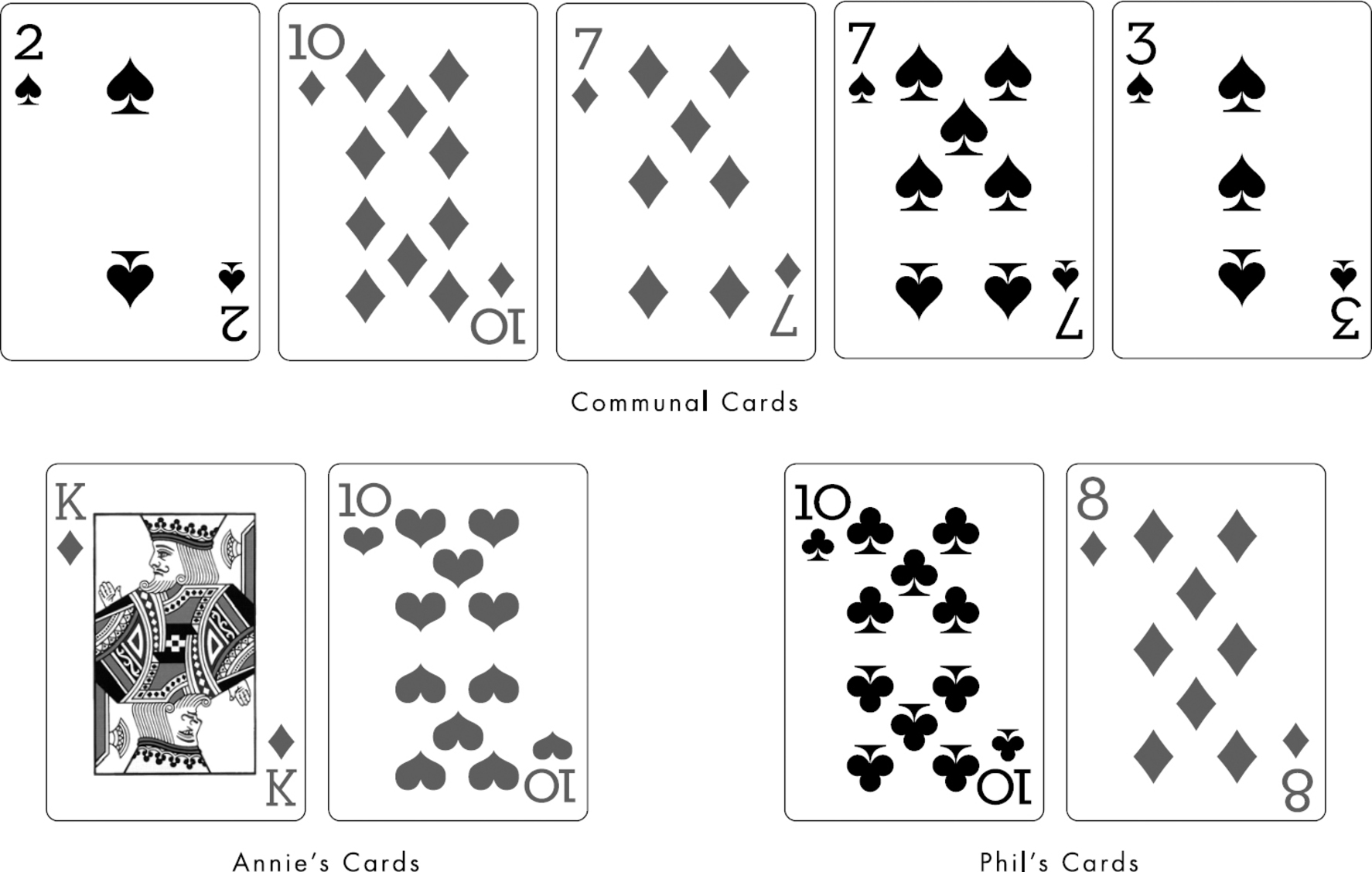

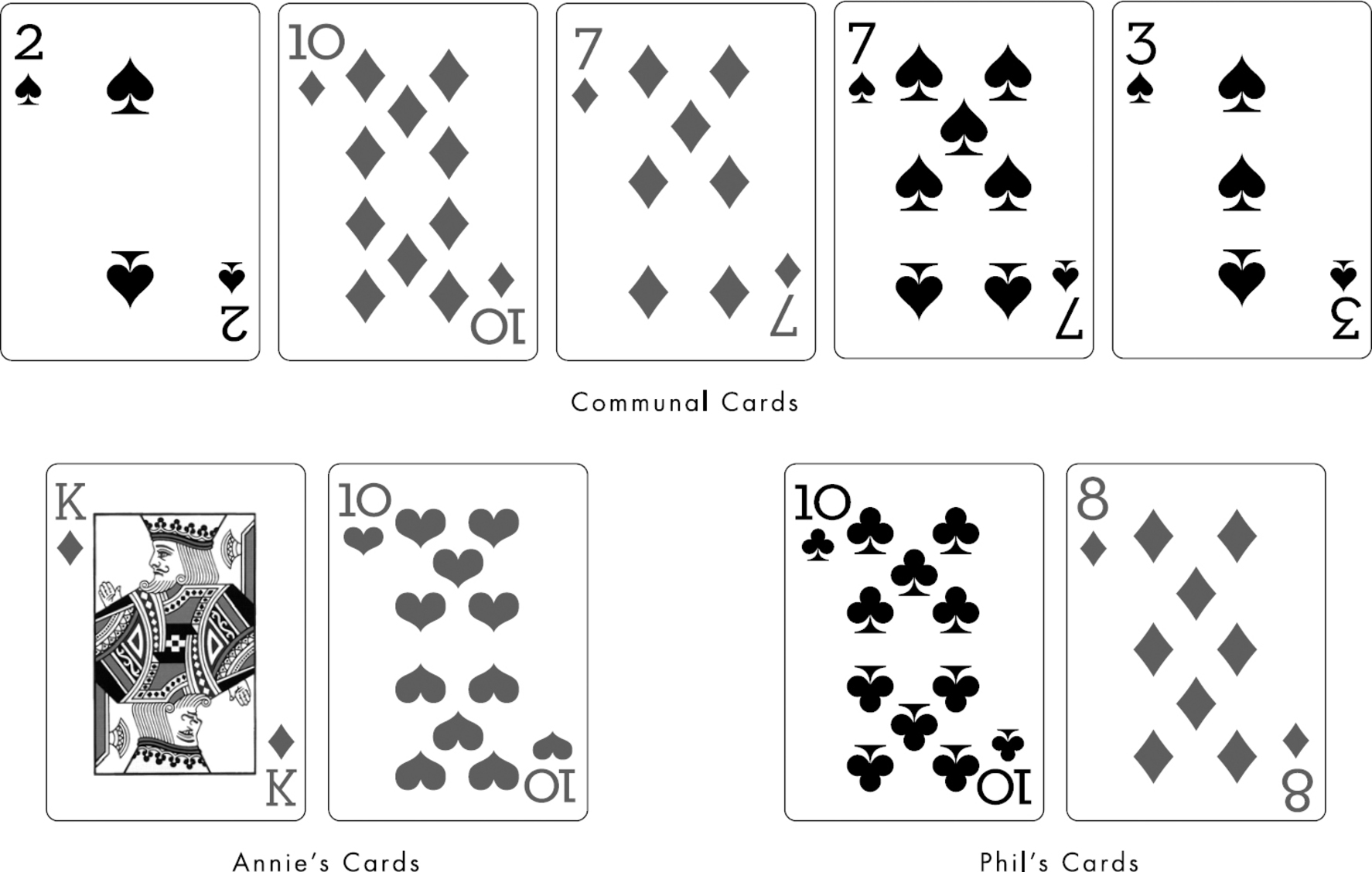

With Annie’s brother out of the competition, there are only two players left at the Tournament of Champions table: Annie and Phil Hellmuth. Hellmuth is a card room legend, a television celebrity known as “the Poker Brat.” “I’m the Mozart of poker,” he told me. “I can read other players probably better than anyone playing, maybe anyone in the world. It’s white magic, instinct.”

Annie is at one end of the table, Hellmuth at the other. “I had a good idea of how Phil viewed me at that point,” Annie said later. “He’s told me before that he has a low opinion of my creativity, that he thinks I’m more lucky than smart, that I’m too scared to bluff when it matters.”

That’s a problem for Annie, because she wants Phil to think she’s bluffing. The only way she can lure him into a big pot is by convincing him she’s bluffing when, in fact, she isn’t. To win this tournament, Annie needs to force Phil to change his assumptions of her.

Phil, though, has a different plan. He believes he’s the stronger player. He believes he can read Annie. “I have this capacity to learn very, very quickly,” he told me. “When I know what people are doing, I can control the table.” Those aren’t idle boasts. Hellmuth has won fourteen poker championships.

Annie and Phil have roughly equal piles of chips. For the next hour, they play hand after hand, neither gaining a clear advantage. Phil keeps subtly trying to throw Annie off, to make her mad or lose her cool.

“I would have preferred to play your brother,” he says.

“This is all right,” Annie replies. “I’m just happy to be in the finals.”

Annie bluffs Phil four times. “I wanted him to reach the breaking point where he says, ‘Screw this, she’s bluffing me hand after hand and I gotta fight back,’ ” Annie said. But Phil doesn’t seem shaken. He doesn’t overreact.

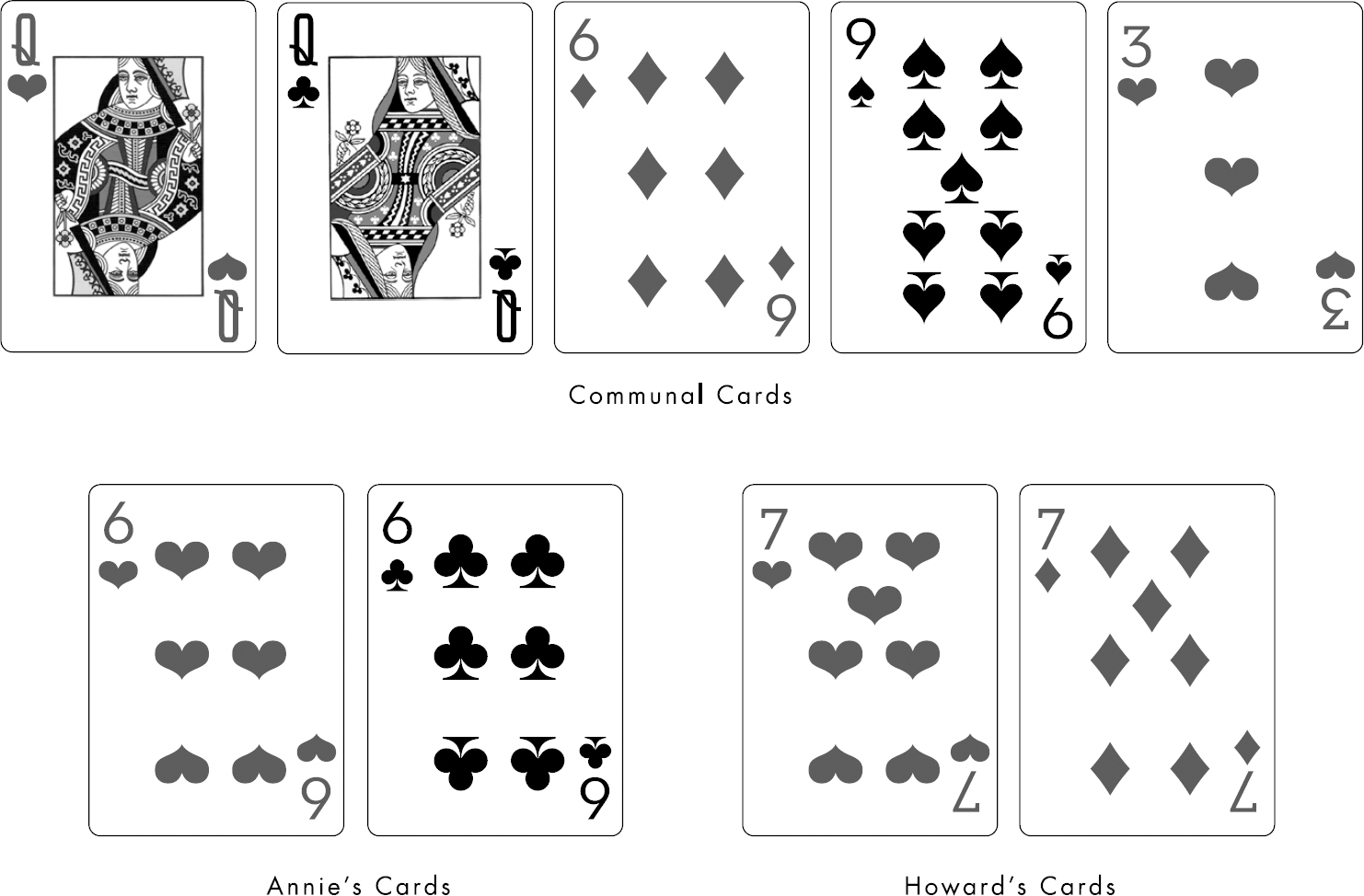

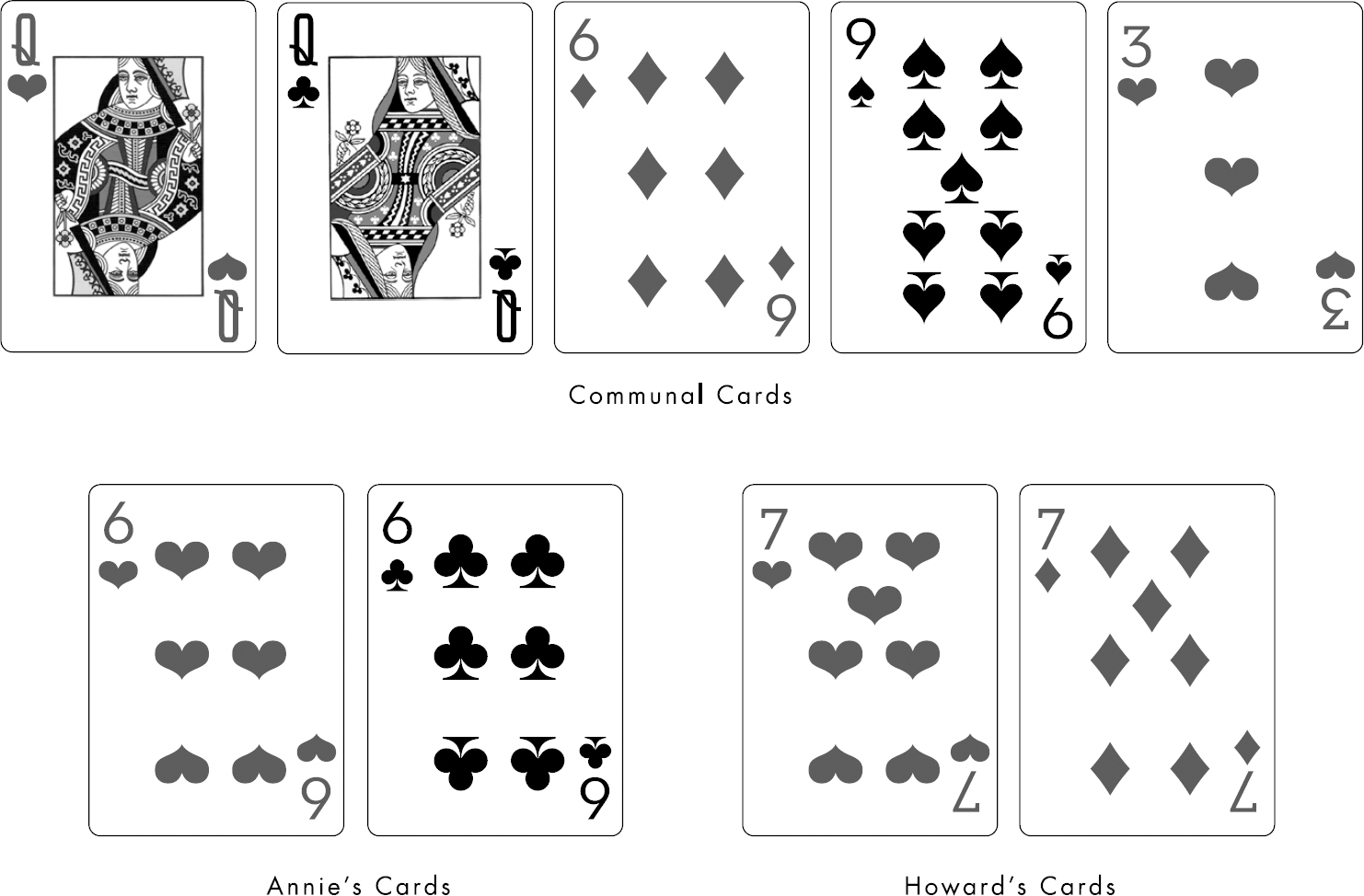

Finally, Annie gets the hand she’s been waiting for. The dealer gives her a king and a nine. Phil receives a king and a seven. In the middle of the table, the dealer lays down a communal king, six, nine, and jack.

Phil knows he has a pair of kings. But unbeknownst to him, Annie has two pair—kings and nines. Neither sees what the other is holding.

It’s Annie’s bet, and she raises $120,000. Phil, thinking his pair of kings is likely the strongest hand at the table, matches it. Then Annie goes all in, bringing the pot to $970,000.

The bet is now to Phil.

He starts muttering to himself. “This is unbelievable,” he says out loud. “Really unbelievable. She might not even know how strong I am here. I’m not sure she fully even understands the value of the hand.”

He stands up.

“I don’t know,” he says, pacing around the table. “I don’t know, I have a bad feeling about this hand.” He folds.

Phil flips over his king, showing Annie that he had a pair. Then Annie strikes: She casually turns over one of her cards—but not both—showing Phil her pair of nines, but not revealing that she also had a pair of kings.

“I wanted to force him to change his assumptions about me,” Annie later said. “I wanted him to think I was bluffing with a pair of nines.”

“Wow, did you really just push in with a nine?” Phil says to Annie. “That’s so reckless, especially against someone like me. Maybe I acted too fast.”

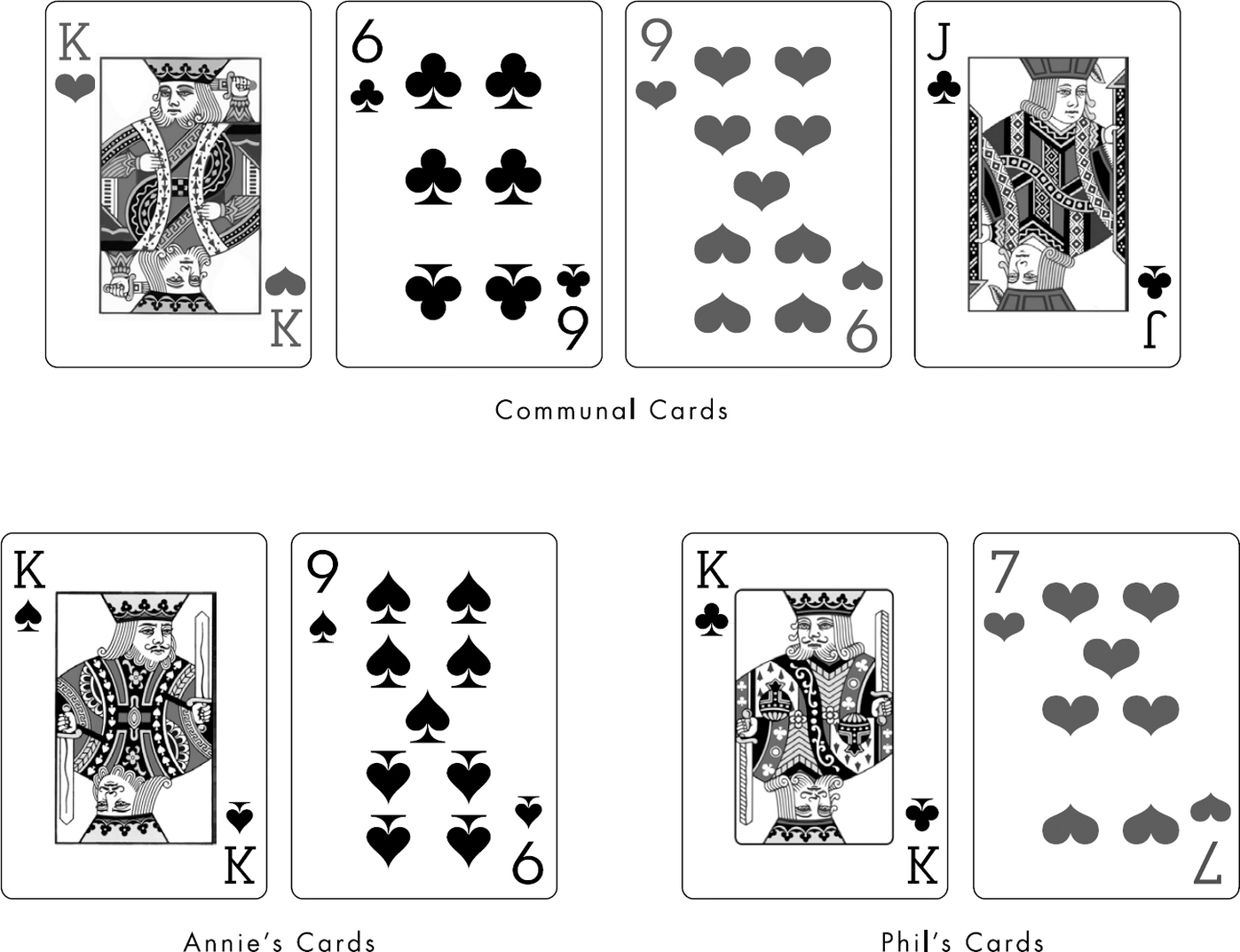

The players ready for the next hand. Annie has $1,460,000 in chips; Phil has $540,000. The dealer gives them their cards. Annie has a king and a ten; Phil a ten and an eight. The first communal cards come out as a two, ten, and seven.

Phil has a pair of tens, with an eight backing it up. It’s a good hand. Annie also has a pair of tens, with a king, slightly better.

Phil pushes $45,000 into the pot. Annie raises $200,000. It’s an aggressive move. But Phil is starting to believe that Annie is playing recklessly. He thinks he sees a pattern he didn’t expect from her: She’s bluffing and bluffing and bluffing again. Phil’s base rate is gradually shifting.

Phil looks at the pile of chips on the table. Maybe his assumption that Annie is too scared to bluff at critical moments is wrong? Maybe Annie is bluffing right now? Maybe she’s finally overplayed her hand?

“I’m all in,” Phil says, pushing his stack into the middle of the table.

“I call,” Annie says.

Both players turn over their cards.

“Shit,” Phil says, seeing that they both have a pair of tens—and that Annie has the high card, a king to Phil’s eight.

The dealer puts a seven on the table, benefiting neither player.

Annie is now standing, gripping her cheeks. Phil is also on his feet, breathing hard. “Give me an eight, please,” he says. It’s the only card that will keep him in the game. The dealer turns over the final communal card. It’s a three.

Annie wins the $2 million. Phil is out. The game is over. Annie is the champion.

Later, she will tell people that winning this tournament changed her life. It made her, in effect, the most famous female poker player on earth. In 2010, she went on to win the National Heads-Up Poker Championship. Today, she holds a record for World Series of Poker profits. In total, she’s won more than $4 million. She doesn’t worry about her mortgage anymore. She doesn’t have panic attacks. In 2009, she appeared on a season of Celebrity Apprentice. She was a little nervous before the filming started, but not too much. There were no anxiety breakdowns. She doesn’t play in many poker tournaments these days. She spends most of her time giving lectures to businesspeople about how to think probabilistically, about how to embrace uncertainty, about how, if you commit to a Bayesian outlook, you’ll make better decisions in life.

“A lot of poker comes down to luck,” Annie told me. “Just like life. You never know where you’ll end up. When I checked myself into the psych hospital my sophomore year, there’s no way I would have guessed I would end up as a professional poker player. But you have to be comfortable not knowing exactly where life is going. That’s how I’ve learned to keep the anxiety away. All we can do is learn how to make the best decisions that are in front of us, and trust that, over time, the odds will be in our favor.”

How do we learn to make better decisions? In part, by training ourselves to think probabilistically. To do that, we must force ourselves to envision various futures—to hold contradictory scenarios in our minds simultaneously—and then expose ourselves to a wide spectrum of successes and failures to develop an intuition about which forecasts are more or less likely to come true.

We can develop this intuition by studying statistics, playing games like poker, thinking through life’s potential pitfalls and successes, or helping our kids work through their anxieties by writing them down and patiently calculating the odds. There are numerous ways to build a Bayesian instinct. Some of them are as simple as looking at our past choices and asking ourselves: Why was I so certain things would turn out one way? Why was I wrong?

Regardless of our methods, the goals are the same: to see the future as multiple possibilities rather than one predetermined outcome; to identify what you do and don’t know; to ask yourself, which choice gets you the best odds? Fortune-telling isn’t real. No one can predict tomorrow with absolute confidence. But the mistake some people make is trying to avoid making any predictions because their thirst for certainty is so strong and their fear of doubt too overwhelming.

If Annie had stayed in academics, would any of this have mattered? “Absolutely,” she said. “If you’re trying to decide what job to take, or whether you can afford a vacation, or how much you need to save for retirement, those are all predictions.” The same basic rules apply. The people who make the best choices are the ones who work hardest to envision various futures, to write them down and think them through, and then ask themselves, which ones do I think are most likely and why?

Anyone can learn to make better decisions. We can all train ourselves to see the small predictions we make every day. No one is right every time. But with practice, we can learn how to influence the probability that our fortune-telling comes true.

*1 Poker is a game of odds within odds. While this example provides an explanation of probabilistic thinking (and the concept of “pot odds”), it is worth noting that a full analysis of this hand is slightly more complex (and would take into account, for instance, the other players at the table). For a more nuanced analysis, please see the notes for chapter 6.

*2 Bayes’ rule, which was first postulated by the Reverend Bayes in a posthumously published 1763 manuscript, can be so computationally complex that for centuries most statisticians essentially ignored the work because they lacked tools to perform the calculations it demanded. Starting in the 1950s, however, as computers became more powerful, scientists found they could use Bayesian approaches to forecast events that were previously thought unpredictable, such as the likelihood of a war, or the odds that a drug will be broadly effective even if it has only been tested on a handful of people. Even today, though, calculating a Bayesian probability curve can, in some cases, tie up a computer for hours.