SEE ALSO asset-based community development; community; Health Impact Assessment; needs assessment

Capacity building is a process that increases assets and attributes through increasing the knowledge, skills and competencies of the different partners to lead to greater sustainability (Gibbon, Labonte and Laverack, 2002).

Capacity building has developed in public health because of the requirement to prolong programme gains, especially for community groups to address their own health concerns. Capacity building has been used as a systematic approach to build the assets of others within a programme context. Community capacity building is the increase in community groups’ ability to define, assess, analyse and act on health (or any other) concerns of importance to their members (Labonte and Laverack, 2001a). Whilst there is a broad body of literature in regard to the definition of community capacity, there is less in regard to how to make this concept operational in a public health programme context. But in recent years community capacity has been unpacked into the organizational areas of influence that contribute to its development (Laverack, 2007). The nine capacity domains, for example, represent those aspects of the process of community capacity that allow individuals and groups to better organize and mobilize themselves towards gaining greater control of their lives. A capable community has strong organizational and social abilities that are reflected by the nine domains to encompass stakeholder participation, local leadership and organizational structures, problem assessment capacities, stakeholder ability to ‘ask why’, resource mobilization, links to other organizations, an equitable relationship with outside agents and stakeholder control over programme management (Laverack, 2007).

Approaches to build community capacity enable people to better organize themselves, to strategically plan for actions to resolve their circumstances and to evaluate the outcomes, for example:

•A period of observation and discussion is important to first adapt the approach to the social and cultural requirements of the participants. For example, the use of a working definition of community capacity building can provide all participants with a more mutual understanding of the concept in which they are involved and toward which they are expected to contribute;

•Measurement is in itself insufficient to build capacity as this information must also be transformed into actions. This is achieved through strategic planning for positive changes to achieve improvements at an individual and a community level. The participants usually develop a detailed strategy based on identifying specific activities; sequencing activities into the correct order to make an improvement; setting a realistic time frame including any targets; and assigning individual responsibilities to complete each activity within the programme time frame. The resources that are necessary and available to improve the present situation will also have to be assessed.

The early experiences of the evaluation of capacity building used qualitative information to provide transcribed interviews which were difficult to interpret. The lessons learnt have provided the basis for approaches that can enable people to visually represent the capacity building process as a graphic image in a format that anyone can understand. The information can be compared over a specific timeframe and between the different components of a programme.

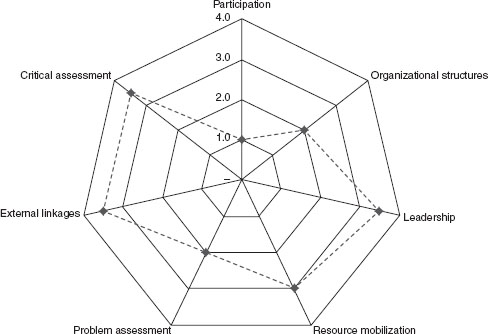

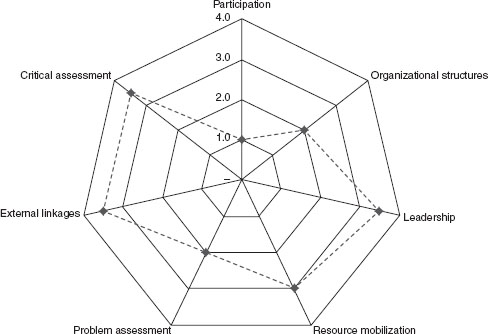

Visual representations that are culturally sensitive and easy to reproduce are a useful way to interpret and share qualitative information. The visual representation is also an attractive option because it can show results in a way that can be easily understood by all stakeholders. The spider web configuration is specifically designed to be used with the ‘domains approach’ discussed above. It can be easily constructed by using any spreadsheet package that allows quantitative information to be graphically displayed. The visual representation shows the strengths and weaknesses of each domain and this information can be used to compare progress within a community and between communities in the same programme. A textual analysis usually accompanies the visual representation to explain why some domains are strong and others are not (Laverack, 2007). Figure 1 provides the example of a completed spider web configuration and subsequent measurements can be carried out and then plotted onto the same visual representation. Over the life time of the programme an image of community capacity, as it increases or decreases, can then be easily plotted.

FIGURE 1 Spider web for community capacity

Source: Laverack, 2005, p. 104.

KEY TEXTS

•Goodman, R. M. et al. (1998) ‘Identifying and Defining the Dimensions of Community Capacity to Provide a Basis for Measurement’, Health Education and Behavior, 25 (3): 258–278

•Labonte, R. and Laverack, G. (2001a) ‘Capacity Building in Health Promotion, Part 1: For Whom? And for What Purpose?’ Critical Public Health, 11 (2): 111–127

•Labonte, R. and Laverack, G (2001b) ‘Capacity Building in Health Promotion, Part 2: Whose Use? And with What Measure?’ Critical Public Health, 11 (2): 129–138

SEE ALSO activism; counter tactics; injury; schools; sexual health; youth

Child protection refers to preventing and responding to violence, exploitation and abuse against children including commercial sexual exploitation, trafficking, child labour and harmful traditional practices, such as female genital cutting. Child protection is also associated with the terms child abuse, child neglect, child exploitation and child maltreatment (UNICEF, 2006).

Child maltreatment, for example, refers to the physical, sexual, mental abuse and/or neglect of children younger than 18 years (WHO, 2013c).

The convention on the rights of the child (UNICEF, 1990) outlines the fundamental rights of children. Article 19 states that children have the right to be protected from being hurt and mistreated, physically or mentally. Governments have a duty to ensure that children are properly cared for and protect them from violence, abuse and neglect by their parents or anyone else who looks after them. The convention on the rights of the child is the international reference point that sets the standards for child protection and to which most UN member states have endorsed.

Child protection (sometimes called child guarding) programmes target children who are vulnerable to abuse or are subjected to violence, exploitation and neglect. These children are sometimes at risk of death and suffer poor physical and mental health, educational problems, displacement, homelessness, vagrancy and poor parenting skills later in life. Child protection or child welfare services have duties towards children in need of care and protection and cover the provision of advice, accommodation and care of vulnerable children and, where the law allows, to initiate proceedings for the removal of children from the care of their parents.

Building a protective environment for children has been identified as involving eight essential components: (1) strengthening government commitment and capacity to fulfil children’s right to protection; (2) promoting the establishment and enforcement of adequate legislation; (3) addressing harmful attitudes, customs and practices; (4) encouraging open discussion of child protection issues that includes media and civil society partners; (5) developing children’s life skills, knowledge and participation; (6) building capacity of families and communities; (7) providing essential services for prevention, recovery and reintegration, including basic health, education and protection; (8) establishing and implementing ongoing and effective monitoring, reporting and oversight (UNICEF, 2006).

Approximately 126 million children aged 5–17 years are believed to be engaged in hazardous work (ILO, 2006) that can be detrimental to their early development. It is considered inappropriate if a child below a certain age works and an employer is usually not permitted to hire a child below a certain minimum age depending on the country and the type of work involved. Child labour refers to the employment of children at regular and sustained work and is considered exploitative by many international organizations and is illegal in many countries. However, child labour remains in, for example, factory work, mining, prostitution, agriculture and in the informal sectors, such as selling items on the street or begging, in many developing countries. Campaigners have pursed the reform of child labour laws and international working conditions. StopFirestone (Stop Firestone, 2012), for example, is a campaign of the Stop Firestone Coalition, a group made up of both US and Liberia-based organizations. A key focus has been the Firestone Tyre and Rubber Company’s operation in Liberia including a rubber plantation in which children were reported to have been made to work for excessively long hours to fulfil a high production quota. The Firestone Tire and Rubber Company denied these claims and started a concerted counter campaign stating that it has helped families and children through education and has applied better employment standards. The International Labour Rights Fund filed a lawsuit against the company in 2005 on behalf of current child labourers and their parents who had also worked on the plantation as children. In 2007 Firestone’s motion to dismiss the case was denied and the lawsuit was allowed to proceed (Knudsen, 2007). Concerns have been raised that campaigns to stop child labour may force children to turn to even more dangerous sources of income. UNICEF, for example, has estimated that 50,000 children were dismissed from their garment industry jobs in Bangladesh following the introduction of the Child Labour Deterrence Act in the United States in the 1990s. Many children then resorted to jobs such as stone-crushing, street hustling, and prostitution – jobs that are more hazardous and exploitative than garment production. The study suggests that some tactics such as product boycotts can have long-term negative consequences that actually harm rather than help children employed in low-income jobs (UNICEF, 2001).

The Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNICEF, 1990) has helped to achieve declines in infant mortality, a rise in school enrolment and better opportunities for girls. However, in spite of these gains there are many children who are still deprived of their rights and inequalities still exist especially for children who are vulnerable (WHO, 2013c).

KEY TEXTS

•Daniel, B. (2010) Child Development for Child Care and Protection Workers. 2nd edn (London: Jessica Kingsley)

•Lonne, B. et al. (2008) Reforming Child Protection (New York: Routledge)

•UNICEF (1990) ‘The Convention on the Rights of the Child’. General Assembly Resolution 44/25. Definition for the Concept of Gender Mainstreaming (London: UNICEF), p. 27

SEE ALSO definition; globalization; Health Impact Assessment; malnutrition

Climate change refers to any change in climate over time, whether due to natural causes or as a result of a human activity and can lead to increased vulnerability for poor health (WHO, 2011).

Three basic pathways have been identified by which climate change affects health:

1.Direct impacts, which relate primarily to changes in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events including heat, drought and heavy rain;

2.Effects mediated through natural systems, for example, disease vectors, water-borne diseases and air pollution; and

3.Effects mediated by human systems, for example, occupational impacts, under-nutrition, and mental stress (IPCC, 2014).

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has projected that the effects of climate change on public health will occur through greater risk of injury, disease, and death due to more intense heat waves, increased risk of under-nutrition resulting from diminished food production in poor regions, increased risks of food and water-borne diseases and vector-borne diseases. Other factors that can contribute towards vulnerability to ill health associated with climate change include a poor education, low income, existing poor health status and, significantly, a lack of responsiveness by government. In practice these factors can combine, often in a complex and place-specific manner, to have a greater influence on vulnerability (IPCC, 2014).

The effects of climate change on health are predicted to impact on most populations in the coming decades and to put the health of billions of people at increased risk (Pachauri and Reisinger, 2007). However, climate change may also bring health benefits to some; for example, milder winters may reduce deaths from influenza, while mosquito populations may recede in areas that become more arid (McMichael, Montgomery and Costello, 2012). The present health status of any population is the single most important predictor of the future health impact of climate change. Populations that do not have access to quality health care and essential public health services are more likely to be adversely affected by climate change (Frumkin and McMichael, 2008). The degree to which public health measures will need modification to address additional pressures from climate change will depend on the current burden of ill health, the effectiveness of current interventions, projections of where, when and how the health burden could change with climate change and the feasibility of implementing additional programmes (Ebi et al., 2006).

Future public health efforts to adapt to the health impacts of climate change have been categorized as incremental, transitional and transformational actions (O’Brien et al., 2012). Incremental actions include improving public health and health care services for climate-related health outcomes, without necessarily considering the possible impacts of climate change – for example, the use of vaccination to prevent seasonal outbreaks of climate-sensitive pathogens such as the rotavirus. Transitional action means shifts in attitudes and perceptions, leading to initiatives such as vulnerability mapping and improved surveillance systems that specifically integrate environmental factors. For example, integrated monitoring of food-borne and animal diseases and improved methods to detect pathogens and contaminants in food. Transformational adaptation requires fundamental changes in public health systems and has yet to be implemented.

The health risks associated with climate change have been classified into four broad areas and the public health sector has an important role to play in communicating these risks to the general public: (1) Immediate and direct risks include the impacts of heat waves, extreme weather events and altered air quality such as increased pollutants and concentrations of ground level ozone. Adverse temperature changes, for example, increase in the demand for electricity and thus combustion of fossil fuels, generating airborne particulates and indirectly leading to increased respiratory disease from pollution. Over a longer time period, increased temperatures can create drought and ecosystem changes that can result in shortages of clean water. (2) Indirect risks arise from disruptions to ecological and biophysical systems, affecting food yields, the production of spores and pollen, bacterial growth rates and the range and activity of disease vectors. (3) Deferred and diffuse risks to health include those associated with rural displacement and the mental health consequences of, for example, droughts in rural communities. The emotional and psychological effects can last for long periods affecting community well-being and the capacity for recovery. (4) Risks associated with conflict resulting from climate change and refugee movements, for example, storm surges in coastal areas coupled with rising sea levels can, on a global scale, threaten critical infrastructure and result in mass population movement and conflict, with significant health impacts (McMichael, Montgomery and Costello, 2012).

Adaptation to the impact of climate change on health is essential. The most effective measures include programmes that implement basic public health measures such as provision of clean water and sanitation, secure essential health care including vaccination and child health services, increase capacity for disaster preparedness, early warning systems and response mechanisms. The value of adaptation to extreme weather and climate events can be demonstrated, for example, when cyclone Bhola hit East Pakistan (present-day Bangladesh) in 1970 with approximately 500,000 deaths. In 1991, a cyclone of similar severity caused about 140,000 deaths but in November 2007 a cyclone resulted in far fewer deaths (approximately 3400) even though the population had grown by more than 30 million in the intervening period (Mallick et al., 2005). Bangladesh achieved this reduction in mortality through effective collaborations between governmental and non-governmental organizations and local communities and by improving general disaster education and early warning systems. Enhancing disease surveillance, monitoring environmental exposures, improving disaster risk management and facilitating coordination between health and other sectors can therefore be important preventive measures (Woodward, Lindsay and Singh, 2011). Impacts on health can also be reduced by social and economic development, particularly among the poorest and least healthy groups in society.

A key uncertainty is the extent to which governments will strengthen their systems and services to respond to climate change. There is little evidence of the complex disease pathways such as the effect of extreme weather on water and sanitation and disease. More relevant research is necessary in improved vulnerability and adaptation assessments, the effectiveness of health adaptation measures and an assessment of the health co-benefits of alternative climate mitigation policies.

KEY TEXTS

•Butler, C. (ed.) (2014) Climate Change and Global Health (Wallingford, UK: CABI)

•McMichael, T., Montgomery, H. and Costello, T. (2012) ‘Health Risks, Present and Future, from Global Climate Change’, British Medical Journal, 344: e1359

•World Bank (2010) ‘Development and Climate Change’. World Development Report 2010. (Washington DC: The World Bank)

SEE ALSO behaviour change; epidemiology; hygiene; prevention paradox; risk communication; sexual health

Communicable disease, also called infectious and transmissible disease, comprises illnesses resulting from the infection, presence and growth of pathogenic and biological agents in individuals and in population groups (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2013).

An infectious disease is transmitted from a source, such as from one person to another or from a vector to a person. Identifying the means of transmission is an important part in understanding the biology of a communicable disease and in its prevention. Infectious pathogens include viruses, bacteria, fungi and protozoa. Communicable disease prevention interventions focus on controlling or eliminating the cause of transmission, the vector or a high-risk behaviour. In some cases this can be done using a physical method, for example, a condom for preventing the spread of a sexually transmitted disease. For other communicable diseases a vaccine can be used to reduce the effect of the disease, such as for measles (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2013).

Globally, the main causes of morbidity and mortality from communicable diseases are from viral hepatitis, HIV, influenza, malaria, polio and tuberculosis. Viral hepatitis, which affects the liver, is a group of infections referred to as hepatitis A, B, C, D and E. It is responsible for more than 1.4 million deaths annually, mostly in low- and middle-income countries. This public health threat rivals the number of deaths from HIV/AIDS (1.7 million), tuberculosis (1.4 million) and malaria (700,000) worldwide (WHO, 2009a). Hepatitis B and C cause approximately 80% of liver cancers. A key concern about viral hepatitis is co-infection among people living with HIV which can increase the risk of both serious liver disease and more rapidly progressive HIV infection. The World Health Organization estimates that 33 million people were infected with HIV, the majority of cases (22 million) of which are in Sub-Saharan Africa. The most successful interventions to fight AIDS have been efforts to make available antiretroviral (ARV) drugs, education and outreach to prevent the spread of HIV (WHO, 2009a). An HIV-infected mother can pass the infection to her infant during pregnancy, delivery and through breastfeeding. ARV drugs given to either the mother or HIV-exposed infant reduces the risk of transmission. Breastfeeding and ARVs together have the potential to significantly improve infants’ chances of surviving while remaining HIV uninfected. WHO recommends that when HIV-infected mothers breastfeed, they should receive ARVs and follow WHO guidance for infant feeding (WHO, 2013a). Influenza (including avian and swine flu) affects many people and extensive international coordination is required in surveillance, detection and response. An influenza pandemic occurs when a new flu virus emerges for which there is little or no immunity in the human population and therefore spreads easily person-to-person worldwide.

A pandemic is an epidemic that occurs on a scale crossing international boundaries, usually affecting a large number of people, and involves a disease or condition that is infectious (Porta, 2014). The Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) virus, for example, killed 800 people in the Asia/Pacific region in 2002 and was spread via the respiratory route or by hand-to-face transmission following contact with contaminated surfaces. If the SARS virus had emerged prior to the development of the germ theory of infectious disease it may have caused far greater mortality. Rigorous sanitation procedures and barrier nursing (latex gloves, face masks, disposable gowns) when in contact with infected patients helped the disease being contained in humans. The emergence of the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) virus, which has caused a few human cases and may be maintained in nature as an asymptomatic infection of camels, is similarly being closely monitored (Doherty, 2013).

Malaria is a preventable parasitic disease transmitted by mosquitoes and is prevalent especially in Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia. There were an estimated 219 million cases of malaria and 660,000 deaths in 2010. The focus areas involved in combating malaria include public health information, research, prevention and control, case management and regulating diagnostic tests and vaccine development (World Health Organization, 2014c).

Polio tends to infect children under five years causing lifelong crippling conditions by a virus that invades the nervous system. There is no cure for polio, but there are vaccines, which means the strategy to eradicate the disease is focused on prevention through, for example, proper sanitation and hygiene practices. The Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) achieved a 99% reduction in polio cases worldwide between 1988 and 2000 but this was followed by a decade of limited eradication (Global Polio Eradication Initiative, 2014).

Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) is a haemorrhagic fever that causes death in 50–90% of clinically diagnosed cases. Ebola refers to a genus and not to a specific virus with at least four subtypes (Zaire, Sudan, Reston and Ivory Coast). The virus is thought to originate from an animal source, such as from fruit bats, but the exact source is inconclusive. There is presently no vaccine to prevent or antivirus to treat this disease which has an incubation period of 3–21 days and symptoms of high fever, vomiting, external and internal bleeding and diarrhoea. Transmission is through contact with body fluids such as vomit, blood and sweat. People who have recovered from EVD can still pass on the virus, for example, through semen during sexual intercourse. Unless isolated, this type of a disease poses a substantial pandemic threat to public health (Hewlett and Hewlett, 2008).

Tuberculosis (TB) is a disease caused by bacteria spread through the air from one person to another and commonly attacks the lungs. It is estimated that one-third of the world’s population is infected with TB, with 85% of cases occurring in 22 countries, nine of which are in Sub-Saharan Africa. A drug regimen using Directly Observed Therapy (DOTS) over a six–eight-month period is the standard treatment for TB but failure to complete the short course regime can result in drug resistance including multi-drug resistance (Global Health, 2014).

Drug resistance is the reduction in effectiveness of a drug in treating a disease or condition because of the resistance by some pathogens that have evolved. Some pathogens can be multi-drug resistant. The development of antibiotic resistance, for example, derives from some drugs targeting only specific bacterial proteins and therefore any mutation in these proteins interfere with its destructive effect, resulting in antibiotic resistance. It has been the lack of a committed strategy by governments and the pharmaceutical industry that has allowed organisms to develop resistance at a rate that has been faster than new drug development. Drug resistance can sometimes be minimized by using a combination of multiple drugs, for example, in the treatment of tuberculosis, and works because individual mutations can be independent and may tackle only one drug at a time (National Research Council, 2003).

Neglected tropical diseases are a group of infections endemic in low-income populations in Africa, Asia and the Americas. Some have preventive measures or acute medical, low-cost treatments which are available in the developed world but which are not universally available in poorer countries. Neglected tropical diseases are contrasted with the big three communicable diseases (HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria) which generally receive greater preventive and treatment resources. The neglected diseases include dengue, guinea worm disease, leishmaniasis, leprosy, lymphatic filariasis, schistosomiasis, trachoma and chagas disease.

An innovative way to decrease the transmission rate of infectious diseases is to recognize the effects of interactions within hubs (or groups) of infected individuals and other interactions within discrete hubs of susceptible individuals. Despite the low interaction between discrete hubs, the disease can jump to, and spread in, a susceptible hub via a single or few interactions with an infected hub. Infection rates can be reduced if interactions between individuals within infected hubs are eliminated but can be drastically reduced if the main focus is on the prevention of transmission jumps between hubs. The use of needle exchange interventions in areas with a high density of drug users with HIV is an example of the successful implementation of this type on an initiative (Watts, 2003).

KEY TEXTS

•Hawker, J. et al. (2012) Communicable Disease Control and Health Protection Handbook. 3rd edn (London: Wiley-Blackwell)

•Heymann, D. (2008) Control of Communicable Disease Handbook. 19th edn (Washington DC: American Public Health Association)

•Nathanson, C. A. (2009) Disease Prevention as Social Change: The State, Society, and Public Health in the United States, France, Great Britain, and Canada (New York: Russel Sage Foundation)

SEE ALSO capacity building; needs assessment; participation; volunteerism

A community is a specific group of people, sometimes living in a defined geographical area, who can share a common culture, set of values and norms and are arranged in a social structure according to relationships and function (WHO, 1998).

It is necessary to think beyond the customary view of a community as a place where people live, for example, a neighbourhood or village, because these are often just an aggregate of non-connected people. In many societies, particularly those in developed countries, individuals do not belong to a single, distinct community, but rather maintain membership of a range of communities based on variables such as geography, occupation, social and leisure interests. Communities can have social and geographic characteristics and shared needs that lead them to take action towards achieving mutual goals (Laverack, 2004).

Within the geographic dimensions of community, multiple non-spatial communities exist and individuals may belong to several different ‘interest’ groups at the same time. Interest groups exist as a legitimate means by which individuals can participate to pursue their interests and concerns. Interest groups can be organized around a variety of social activities or can address a shared concern, for example, poor access to public transport (Zakus and Lysack, 1998).

Public health practitioners try to work with the legitimate representatives of a community and to avoid the establishment of a dominant minority that can dictate issues based only on their own concerns and not on those of the majority. Practitioners need to carefully consider if the representatives of a community are in fact supported by its members and that they are not simply acting out of self-interest.

Information and communication technologies have helped to remove some of the physical barriers to communication. Online communities, like traditional forms of community, consist of a diverse group of people but who participate in virtual spaces with little social context and member identity. Social media can encourage communication by enabling participants to find others with whom they share interests and by providing a means to contact them. This facilitates social interactions in online communities and promotes communication by creating chat spaces including ‘global communities’ and ‘digital cities’ by building arenas in which people can interact and share knowledge and mutual interests. Online activity is limited to those who are computer literate and have access to a computer and the internet and this can exclude many people (Nomura and Ishida, 2003).

Civil society is a much broader concept than that of a community as it refers to a diversity of spaces, actors and institutional forms, varying in their degree of formality, autonomy and power. Civil society works through people who create groups, organizations, communities and movements to address shared needs. Civil societies are populated by organizations such as registered charities, non-governmental organizations, community groups, women’s organizations, faith-based organizations, trade unions, self-help groups, social movements, activist and advocacy groups (Laverack, 2007). Civil society has a broad range of intentions, both positive and negative, and there is therefore an element of ‘uncivil society’ that acts as a counterweight to an overly optimistic vision of what civil society is, or can achieve. Ironically, while many policymakers are concerned with the challenge of building civil society in transitional and developing countries, there is a feeling in many industrialized countries that civil society has been degraded and has become less of a feature of everyday life. The concept of civil society has therefore been criticized as a feel-good factor that does not always account for repressive forces in the political arena (Lewis, 2003).

The third sector is a term used to cover all not-for-profit organizations, voluntary, community, charities and social non-government associations. The term ‘third sector’ is in reference to the public sector and the private sector and tends to have a particular focus on social services, the environment and education and is increasingly central to the health and well-being of society (Frumkin, 2005). The third sector can be an indicator of a healthy economy although it has raised concerns about self-regulation and financial accountability. The third sector can also be an indicator of social need not otherwise addressed through public services and is being increasingly relied upon by governments to deliver social and health services.

KEY TEXTS

•Block, P. (2009) Community: The Structure to Belonging (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler)

•Delanty, G. (2003) Community (New York: Routledge)

•Edwards, M. (2009) Civil Society. 2nd edn (Oxford: Polity Press)

SEE ALSO activism; advocacy; child protection; policy change; social movements; tobacco control

Counter tactics are a range of actions designed to influence government, researchers, public opinion and policy analysis in support of a counter cause (Hager, 2009).

Corporations employ counter tactics to help define and shape issues. A major part of this type of public relations work is to challenge opposing agendas and to try to stop their opponents from having an influence. This is achieved, for example, by persistently targeting researchers working on an issue that goes against commercial interests or products in such a way that can suppress the continuation of their work. Meanwhile, corporations cultivate and support favourable researchers by providing helpful funding, travel opportunities and conferences. Corporations also routinely recruit community or professional groups as third parties to give credibility to their agenda. These groups can quickly emerge to support commercial interests or to defend unpopular corporations such as smokers’ rights groups. These groups can present themselves as being independent and/or science-based; for example, pharmaceutical companies will establish patient groups in pursuit of their own interests or engage with existing groups in the debate on policy proposals to add legitimacy to their activities (Allsop, Jones and Baggott, 2004). The well-resourced interest groups can hire lawyers to put pressure on government policies by threatening judicial review and other time-consuming legal challenges. Another counter tactic is election donations. In New Zealand, for example, the alcohol and tobacco industries have been funding political parties and gaining influence for the past century (Hager, 2009).

Counter tactics have been categorized into one of four main strategies: deflect, defer, dismiss and defeat. Opposing stakeholders with power but no passion should be deflected to avoid their involvement in the situation. People with passion but no power, on the other hand, can be defeated, for example, through reaching a compromise. And people with neither passion nor power are dismissed. Countering actions by organizations that have both high passion and high power may require the company to defer to their demands. Even if companies are reluctant their best strategy is to engage with others, to sell an idea and to try and ‘divide and conquer’. The benefits of the collaboration with corporations can include better opportunities for funding. The cost of long-term collaboration is a greater identification with corporations’ policy agendas rather than advocating greater social justice (Burton, 2007).

Corporations also use sponsorship for low-cost marketing such as school, road-crossing jackets with logos displayed on them or providing grants for community development activities. In the United States, for example, food companies, including McDonald’s and Coca-Cola, are responding to the obesity problem with a massive public relations campaign. To protect their interests they market ‘healthier foods’ and try to position themselves as a part of the obesity prevention solution whilst at the same time lobbying against nutrition policies to tax foodstuffs or to limit sales (Simon, 2006).

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) also called corporate conscience or responsible business is a form of self-regulation integrated into a business plan. The goal of CSR is to embrace responsibility for the company’s actions and encourage a positive impact through its activities. Promoting CSR reports has become one of the growth areas in the corporate public relations industry with the role of embracing accountability and transparency as a means to build corporate credibility and reputation (Burton, 2007).

Leverage placed on corporations to change their position on an issue can be achieved by using assets to gain a greater political influence including advocacy, protests, lobbying, boycotts and petitions. The objective remains the same: to add to the level of influence that an individual, group or organization has by harnessing additional assets (Laverack, 2013a).An example of the use of leverage is by the anti-sweatshop movement because garment corporations are vulnerable due to the buyer-driven market that forces them to survive in a highly competitive environment. To make a profit, they must compete with other sellers over consumers looking for good-quality clothing at very affordable prices. To maintain and even improve their market shares and profit margins they outsource their manufacturing to countries where labour is inexpensive and devote resources to marketing. In the weakly regulated setting of outsourced garment manufacturing, worker welfare is jeopardized by the fast and flexible production needed to keep up with fashion. The anti-sweatshop movement has used the vulnerable and competitive situation of the buyer-driven corporate world to lever for an improvement in garment workers’ rights. Wanting profits and a good image among consumers, garment corporations are now being forced to address sweatshop concerns (Micheletti and Stolle, 2007).

Corporations have far more resources than citizens’ groups or health agencies and this enables them to employ sophisticated tactics in support of their interests, sometimes ahead of the public interest. However, these counter tactics can themselves be countered by using a range of low-cost but effective strategies and by gaining public support for a cause.

KEY TEXTS

•Burton, B. (2007) Inside Spin: The Dark Underbelly of the PR Industry (Sydney: Allen & Unwin)

•Hager, N. (2009) Symposium on Commercial Sponsorship of Psychiatrist Education. Speech to the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists Conference, Rotorua, 16 October 2009.

•Simon, M. (2006) Appetite for Profit: How the Food Industry Undermines Our Health and How to Fight Back (New York: Nation Books)

SEE ALSO empowerment; peer education; power; schools; youth

Critical education is a process which allows people to understand the root causes, social context, ideology and personal consequences of an action, policy or discourse (Freire, 2005).

Critical education is also called critical pedagogy, empowerment education, critical consciousness or conscientization. It is an established approach that was first described by the educationalist Paulo Freire (Freire, 2005) in the 1960s as the ability to reflect on the assumptions underlying our actions and to contemplate better ways of living. According to Freire the central premise was that education is not neutral but is influenced by the context of one’s life. The purpose of education is liberation in which people become the subjects of their own learning involving critical reflection and an analysis of their personal circumstances (Wallerstein and Bernstein, 1988). Freire proposed a group-dialogue approach to share experiences and to promote critical thinking by posing problems to allow people to uncover the root causes of their powerlessness. Once critically aware, people can then plan more effective actions to change their circumstances by gradually understanding the causes of powerlessness and by developing realistic actions to begin to resolve the conditions that created them in the first place (Nutbeam, 2000).

A practical application of critical education is through using PhotoVoice, a tool to enable people to identify, represent and enhance their community through a photographic technique. PhotoVoice entrusts cameras to people to enable them to act as recorders and potential catalysts for social action and change in their own communities. People using PhotoVoice engage in a three-stage process that provides the foundation for analysing the pictures they have taken. Stage 1: Choosing those photographs that most accurately reflect the community’s concerns and assets. So that people can lead the discussion, it is they who choose the photographs. They select photographs they consider most significant, or simply like best, from each picture they had taken. Stage 2: Contextualizing or storytelling then occurs in the process of group discussion. Individuals describe the meaning of their images in group discussions and this provides meaning and context. Stage 3: Codifying identifies three types of dimensions that arise from the dialogue process: issues, themes or theories. The individual or group may codify issues when the concerns targeted for action are pragmatic, immediate, and tangible. This is the most direct application of the analysis. The individual or group may also codify themes or develop theories that are grounded in a more systematic analysis of the images (PhotoVoice, 2013).

In an inner city area of Toronto, for example, PhotoVoice has been used to provide images of community issues with a camera by people living in newcomer communities. A story was then created to explain what was important in the pictures using their own words. The images were displayed to the public and recommendations were made to the city authorities regarding bicycle theft due to improperly maintained bicycle racks. This was identified as a common problem and as biking is the main mode of transport for many residents, safe bicycle storage is a daily stressor for many people. The community worked with the city authorities to take an inventory of all bicycle racks, remove broken bicycles from existing racks and to install new racks in the neighbourhood. The decision of the city authorities to remove broken and abandoned bicycles from the neighbourhood was a direct result of the PhotoVoice approach (Haque and Eng, 2011).

Using a critical education approach in public health programmes does involve a considerable commitment to gradually understand the causes of powerlessness and to develop realistic actions to resolve the structural conditions that created them in the first place. However, communities cannot intentionally empower themselves without also having an understanding of the underlying causes of their powerlessness. This is the essential quality of critical education and may occur from within the community, developing slowly and organically, or in the context of a public health programme, it can occur as an intervention, developing as a facilitated process of discussion, reflection and action.

KEY TEXTS

•Freire, P. (2005) Education for Critical Consciousness (New York: Continuum Press)

•Hubley, J., Copeman, J. and Woodall, J. (2013) Practical Health Promotion. 2nd edn (Cambridge: Polity Press)

•Laverack, G. (2004) Health Promotion Practice: Power and Empowerment (London: Sage), Chapter 7.