Chapter 5

Johnny Saves a Sailor

Ten-year-old Johnny stretched his feet out toward the hot fire in Uncle Tom’s library. He dropped his Greek textbook to the floor. Then he opened the new book, Robinson Crusoe, that Uncle Tom had given him just the night before.

“I must put my name in this,” he said aloud. He found a quill pen in his uncle’s desk.

He scratched out on the first page:

John Hancock his book, November, 1747.

He smiled proudly as he looked at his writing. At last he could write a neat line, even though the letters were big.

Today was a school holiday. He was waiting for Aunt Lydia’s callers to leave. Then he and Aunt Lydia would drive to a shoemaker’s shop on King Street. Johnny had outgrown his shoes.

Mrs. Edmund Quincy, who was Sam’s aunt, had brought her newest baby to be admired. Six-month-old Dorothy Quincy was called “Dolly.” Johnny could hear the ladies in the parlor.

“Huh! The way they’re oohing and aahing over Dolly!” he snorted.

“Mistress is ready,” young Cato came to tell him at last.

Aunt Lydia, in her large bonnet and warm red cloak, waited in the open carriage. Uncle Tom had ordered a fine yellow coach from England, but it had not come yet.

First, Aunt Lydia stopped at a dressmaker’s shop. There the dressmaker showed her a new puppet, called a “fashion doll.” It had just come from London and was dressed in the latest style in clothes.

The doll so pleased Aunt Lydia that dusk was coming by the time she reached the cobbler’s shop. The shop faced Long Wharf.

The cobbler measured Johnny’s feet for a pair of shoes with silver buckles and also for a pair of boots. While Aunt Lydia ordered her new shoes, Johnny peered out the shop window. He could see the lights of the British warships that were anchored out in the harbor.

Suddenly he saw eight or ten British sailors running up from Long Wharf. They all carried clubs. They caught three men walking along the waterfront, and dragged two of them back to the wharf and a waiting longboat.

The third man fought his way clear. He ran as fast as he could through the dusk. When he reached the cobbler’s shop, he suddenly turned and darted in through the door. The little bell above the door jangled fiercely, “Ding-a-ling, ding!”

The shoemaker, Johnny, and Aunt Lydia all stared at the panting young man in seaman’s clothes. A black eye and a bloody nose gave him a wild look. He had lost his knitted cap.

“Mercy!” exclaimed Aunt Lydia.

“Hide me!” cried the young man. “The King’s sailors are sweeping the waterfront. They aim to fill their ships’ crews. They’ll be here looking for me in a moment!”

The cobbler found his tongue. “In here.” He opened a door at the back of the shop. “Stay in this back room for a while and hide.”

The young sailor croaked, “My thanks to ye, mate. Send warning. The British are taking landsmen as well as seamen.”

With a quick nod to them all, he slipped through the back door. Everything had happened so fast that Aunt Lydia hadn’t found words. The cobbler gave her a worried look.

“I hope you are not angry with me, Madame Hancock,” he said. “I couldn’t let him be caught. He’s an American seaman in our Boston fishing fleet. The British warships often try to kidnap our sailors. Life on those frigates is so bad the crews run off any chance they get. This is the start of a ‘hot press,’ I vow!”

Aunt Lydia’s eyes shot sparks. “You did right. The idea! How wicked to beat men and take them aboard ships against their will! We must stop this business.”

Johnny had heard talk of the impressment of American seamen before. This was the first time he had seen it happen. His face flushed with anger. He wished he were a grown man. He would go out and stop it!

“Come, Johnny. We must go home.” Aunt Lydia moved toward the shop door.

“Wait, please, Auntie.” Johnny caught her arm. An idea was growing in his mind. “Why can’t we take that sailor with us in the carriage?”

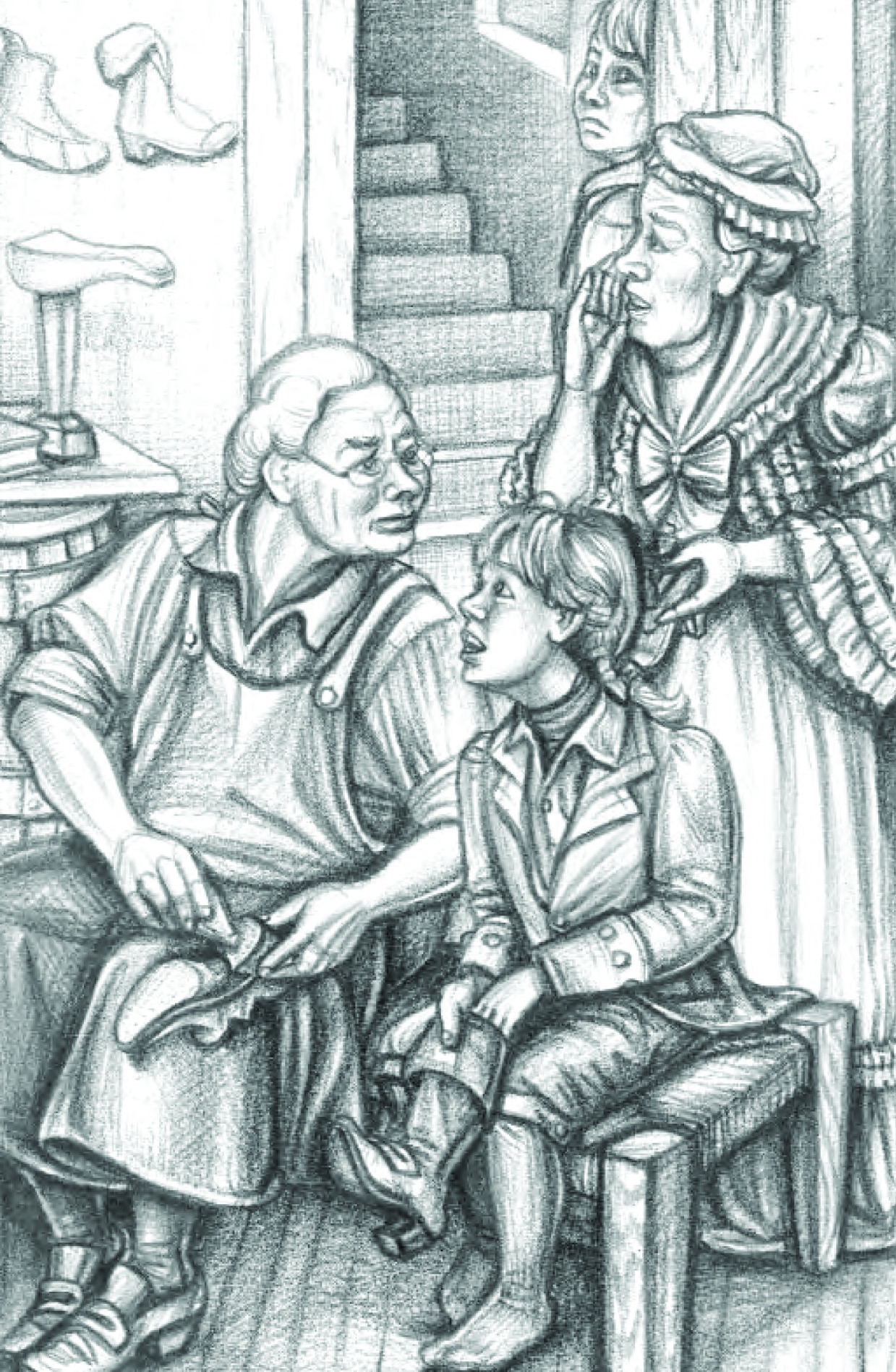

“I don’t know.” Aunt Lydia frowned and thought a moment. Then to Johnny’s relief she smiled and snapped, “We’ll do it. A fine idea!” (Image 5.1)

Image 5.1: “In here.” He opened a door at the back of the shop.

“Stay in this back room for a while and hide.”

Johnny ran outside to tell Prince. How quickly the waterfront had emptied! Somewhere out in the dimness covering the docks, he heard men’s shouts and running feet.

Soon tall, stout Aunt Lydia hurried out to her carriage. Johnny walked on one side of her and Prince on the other. The young Boston sailor crept close behind them. He slipped up on the driver’s seat next to Prince.

In a minute they were off at a fast trot through the empty streets. The soft glimmer of a house light here and there helped to show them the way home.

Back home, the sailor was hidden in the coach house until morning. Uncle Tom in his red velvet cap and blue dressing gown paced his study. He shook his head as Johnny and his aunt told about their adventure.

“It’s that Captain Knowles! He’s a hard man. He cares for nothing but the King’s navy. He’ll seize any man he finds, whether a seaman or a shipbuilder’s apprentice.”

Aunt Lydia sat up straight in her brocaded chair. “We must not allow it. Do something!”

Uncle Tom slapped his hand on his desk. “I will, Madame. In the morning I shall call on the Governor. I’ll insist that he must ask Captain Knowles to return the Americans he’s taken aboard his warships. We have our rights!”

“Good for you, Uncle!” Johnny cried. He was proud of his Uncle Tom. “I wish I could hear you tell the Governor.”

But Uncle Tom did not get to see the Governor. At midday, when Johnny came home from school for the dinner recess, his aunt told him Uncle Tom had sent her word.

“An angry crowd of dock workers, sailors, and the like gathered near the docks early this morning,” she said. “They are armed with sticks, mops, and rusty swords. They’ve seized some British naval officers and threatened the Governor. The town’s in an uproar. You must stay home from school this afternoon, Johnny.”

Late that night Uncle Tom came back. “The members of the Governor’s Council met in the Town House tonight,” he said. “Several thousand people howled outside.”

Johnny knew the Town House. It was the large government building at the head of King Street. Every year each town and village elected a man to sit in the General Assembly. These men met in the Town House.

“The Governor tried to calm the mob,” Uncle Tom went on. “He hopes to get the kidnapped men back.” He looked troubled. “We can’t have mob rule. Yet we are free Englishmen. We won’t be treated as slaves.”

The next day at school the boys talked excitedly about British Captain Knowles’s threat to bombard the town if his officers were not freed. Several days later a town meeting of all the people was called.

The people of Boston agreed to return the navy officers to their ships. Captain Knowles took the kidnapped Boston men from the holds of his ships. He sent them ashore. Then he set sail. Boston was happy to see him go.

The Thanksgiving holidays came soon after this trouble. The Hancocks spent the day with Johnny’s grandparents in Lexington. Then Johnny went on to Braintree to visit Jay Adams for several days.

Jay listened closely to Johnny’s stories of the Boston riot.

“Won’t King George be angry about the riot?” Jay asked thoughtfully.

“No,” Johnny said, surprised. “It’s not his fault. It’s the Navy’s.”

The two boys climbed the hills of the North Common one day. Only a light powder of snow lay on the ground. On the way they talked about fishing through the ice. “How is Little Turtle?” Johnny asked suddenly. “Did you see him last summer? Do you still fish together?”

Jay grinned. “Aye, and he’s not little. He’s taller than you. He says he wants to be an army scout on our border. His uncle was a scout at the attack on Fort Louisburg.”

Johnny gasped. “There was an Indian there with Sergeant Tim. He climbed into the Grand Battery and opened the gate. What if he were the same man? Wouldn’t that be exciting?”

Jay shrugged and laughed. “Who knows? Maybe yes, maybe no. Race you to our gate!”

When Johnny left the next day, Jay promised to visit him during school holidays in August.