CHAPTER 4

Camouflage of the Spider and Dangers of Centralized School Systems

But it will do some good, and what harm can come of it? This is the common reaction to the arguments of chapter 2 and chapter 3 that just expanding years of schooling and education management information systems (EMIS)–visible inputs alone will do little to raise student learning. Once the problems of learning achievement are recognized, the instinct is to do something to address the problem, and expanding inputs is readily at hand and easy to adopt as the solution. Arguments against input expansion are seen as pessimistic and fatalist: “Don't just do something, stand there!”

Doing the seemingly useful might not just be futile, it can be dangerous. Taking a placebo can be dangerous if it prevents you from seeking out the right diagnosis and pursuing a real cure. Pursuing an agenda of “quality improvement,” defined as exclusively expanding “known” and EMIS-visible inputs, perpetuates an illusion of progress. This illusion protects dysfunctional systems against creating the space for new innovations, against the freedom to experiment, and in particular against the disruptive innovations that ultimately can lead to rapid and sustained pace in improvements in learning.

Evolution has produced an animal world full of deceit and deception. Things are often not what they seem. Camouflage is common. Many animals blend into their surroundings to make it difficult for predators or prey to spot them. Salamanders change color to maintain invisibility. Puffer fish move slowly but are able to blow themselves up to appear much larger (and spikier) than usual.

Camouflage that enhances an animal's survival value by mimicking another species is called isomorphic mimicry. The eastern coral snake is highly poisonous and brightly colored, with black, red, and yellow stripes. The scarlet king snake is not poisonous; it is really just a harmless creature, but it too is brightly colored, with black, red, and yellow stripes. The scarlet king snake enjoys the evolutionary advantages of signaling that it is dangerous without the bother of actually being dangerous. Some species of flies have evolved to look like bees, and even to make a bee-sounding buzz as they fly. The survival pressure of natural selection at times produces mimics, species that derive a survival value from imitating other species’ forms or appearances without any real function attached to that appearance.

The deception of camouflage also works for organizations. Sociologists borrowed the idea of animal isomorphic mimicry and have applied it to organizational ecosystems to describe how many organizations behave (DiMaggio and Powell 1983). Organizations, particularly in fields in which the desired outcomes are complex to produce and hard to assess, can enhance their organizational survival by adopting “best practice” where it doesn't really matter. Such reforms can make them look like functional organizations. Adopting the forms of best practice without any of the underlying functionality that actually characterizes the best practice can produce quick and easy gains in perception. Such organizations can look like successful organizations while lacking any real success.

In this chapter, I argue that many education systems around the world, especially those spider systems dominated by large, top-down ministries of education, are garbed in camouflage and actively seeking to hide disastrous levels of underlying dysfunction. Unfortunately, the camouflage has been effective. By pretending to adopt the pursuit of quality education through the expansion of EMIS-visible inputs, more training, and more formal qualifications, these systems are able to fend off challenges, resist innovations, and delay core reforms integral to improved learning. Some schooling systems are like a Bollywood set, just realistic enough to create the illusion of glitz and glamour for a movie, but nothing more than a façade. Buildings that look like schools but don't produce learning are a façade that deludes children and parents into believing they are getting an education while depriving them of real opportunity.

Chapter 3 argued that the dominant approach to improving school quality in developing countries has been to expand known inputs, leading to higher per student costs, but with little impact on learning outcomes. But state-of-the-art research shows that organizational and systemic changes that change the scope of action, incentives, and accountability of agents in education are vastly more cost-effective in producing higher learning than increasing inputs.

— A large-scale experiment in Andhra Pradesh, India, showed that community-hired teachers produced equivalent (or better) learning outcomes for students, even while earning salaries one-fifth or less the salaries of civil service teachers (Muralidharan and Sundararaman 2010b).

— In Kenya, within the context of class size reductions (from, on average, eighty-two to forty-four students), locally contracted novice teachers on one-year contracts earning one-fourth of what civil service teachers earn substantially outperformed their civil service counterparts (Duflo, Dupas, and Kremer 2012).

— In two states in India, low-cost tutors who taught the lowest-performing students for part of the school day produced substantial gains in performance at very low cost (Banerjee, Cole, et al. 2010).

— Putting cameras in classrooms and requiring teachers to take date-and time-stamped pictures increased student attendance and raised scores substantially at very low cost in NGO-run schools in India (Duflo, Hanna, and Ryan 2010).

— In Punjab, Pakistan, private schools outperformed public schools on measures of mathematics and language performance by a full student standard deviation—even for similar students, at much lower cost (Andrabi et al. 2007).

— Private schools in Kenya outperformed public schools on the standard school leavers’ examination by a full student standard deviation (or more)—even when adjusting for student composition (Bold et al. 2011).

Community-hired teachers. Tracking by ability. Tutoring low-performing students. Low-cost yet high-performing private schools. Simple technological mechanisms to ensure teacher attendance. What is most striking about these innovations that cost-effectively improve student performance is that none is on the “quality improvement” agenda of government school systems in nearly any country in the world. In fact, many of them are viewed by the old-school schooling establishment as a problem (such as the rise of private schooling) or as backward (such as hiring community teachers with less training) or as not quality oriented (such as remedial teaching) or as “old-fashioned” (such as student tracking). But how much of the opposition by education establishments to these innovations is evidence-based and how much is isomorphism?

Value-Subtracting and Rent-Extracting School Systems: Illustrations from Punjab, Pakistan, and Uttar Pradesh, India

One fundamental feature of modern organizations is that people working together, with structured roles and assigned tasks, can, through specialization, cooperation, and coordination, produce a whole that is much more than the sum of its parts. Indeed, one might say, along with venerable authorities like Max Weber, that the essence of modern life is the rise of the bureaucratic organization. This is true in the private sector through the modern economy of “scale and scope,” made real in the early twentieth century in railroads, oil, and banking (Chandler 1977, 1990). The rise of the public sector bureaucracy was a parallel evolution through professionalized armies and autonomous bureaucracies (Carpenter 2001). Even in the nonprofit sector the growth of large-scale political and social and humanitarian organizations led to large organizations and institutionalized bureaucracies. What can now be accomplished by individuals because of the increased value added and productivity made possible by being embedded into large organizations staggers the imagination.

But what if organizations are value subtracting?1 What if hundreds of thousands of people work together in organizations that look modern, with organizational charts, bureaucratic offices, and rules and procedures, yet all of these features are merely a façade? If such bureaucracies are shams, could these workers, such as teachers, be more productive working outside a ministry-run school than in it? Could the whole be much less than the sum of its parts, such that organizations are not just rent extracting (producing less with inputs than possible) but actually value subtracting? Yes. Organizations, including school systems, can be so bad that teachers are absolutely less productive at helping their students learn when trapped inside the spider bureaucracy than when acting completely on their own.

Before moving to rigorous evidence, let me tell a story, perhaps apocryphal, but told to me in the first person by a member of the prestigious Planning Commission of India. As a member of the Planning Commission, he was allocated a government-owned flat with a yard and garden, and was assigned a gardener to keep it up. During his first year of residence he enjoyed the garden, and the gardener worked diligently. At the end of the first year the gardener came to the Commission member and said, “Sir, I am sorry to say you will have to get a new gardener.” “I am sorry to hear that; you have been a good gardener. Are you moving?” “No, sir. I will be starting a new job.” “Oh, that is wonderful. What is your new job?” “Well, I have been gardening your garden as a contractor, and now I have been finally officially hired as a full-time employee of the government.” “Again, that is wonderful; what is your new assignment with the government?” “Ah, sir, I have been assigned to be your gardener, but now that I am assigned as a government servant, you will need a new gardener as a contractor to actually do the work.”

Value-Subtracting Government Schools in Punjab, Pakistan

The LEAPS (Learning and Educational Achievement in Pakistan Schools) study is the result of an unprecedented exercise in Pakistan of measuring school and teacher characteristics and grade three to six student learning, including tracking students across grades (used to calculate the learning profiles shown in chapter 1), with detailed collection of data on schools and their operation in Punjab province. While much useful and relevant research has emerged from LEAPS, one unexpected finding is the proliferation of low-cost, nonreligious private schools. Nearly all of these new schools are not part of any larger organization but rather are stand-alone mom-and-pop operations.

The LEAPS data present a unique opportunity to examine the value added of government education organizations by comparing learning in government schools with all of the potential value added and higher productivity in a formal organization: procedures for hiring teachers, requirements for pre-service training and in-service training, guidance in curriculum, systems of supervision and quality control, economies of scale and scope in inputs, and governmental financial support that allows teacher wages to be independent of student ability to pay. All of this potential value added can be compared to the typical productivity of an independent person with no expertise or experience trying to run a school on his or her own. The main finding is that the government organizations not only do not add value, they subtract it, on three levels.

First, the performance of students in government-run schools is worse: equivalent students learn massively less in government schools than in low-cost private schools. While the LEAPS data are not the result of an experiment, they contain an abundance of information on students and schools, providing estimates of the average learning of the “same” (that is, observationally equivalent) students in government versus private schools (Andrabi et al. 2011). Compared to the gains from inputs in the previous chapter, where the total scope-for-learning gains from all potential EMIS-visible input increases were on the order of 0.1 to 0.2 effect sizes, math learning in private schools was 0.7 effect sizes higher than math learning among equivalent students in public schools. The gaps in English were even higher (in Urdu modestly lower), but the researchers found that the private-public gap was roughly an entire student standard deviation. This gap between the private sector and the public sector is much larger than differences on any other school or household characteristics, such as the gap between children with literate versus illiterate mothers or between poorer versus richer students.

Second, government schools are substantially more expensive, as total costs per student are higher. The average cost per student in government schools is roughly twice as high as in private schools (2,000 rupees per child versus 1,000 rupees per child). This difference is primarily the result of teachers in the public sector making substantially more. The study estimates that an equivalently qualified teacher would make 5,299 rupees in the public sector and 1,619 rupees in the private sector.

Lower learning at higher cost implies even lower efficiency. As a crude measure of learning productivity, the private sector spends 1 rupee per percent correct on the LEAPS assessment while the public sector spends 3 rupees. Thus, the cost per unit of learning is three times as high in government-run schools as in private schools.

Third, and perhaps most striking, the inequality of school quality across schools is much higher in the government-run schools than in the private schools. One thing you might expect large spider bureaucracies to produce is uniformity. Many think one advantage of a top-down spider system is that it can ensure equality across schools so that, while public schools might be mediocre, they are at least uniformly mediocre. But this is not always so. As it turned out, many of the best schools were public sector schools, but all of the worst schools were public sector schools. When spider systems turn dysfunctional the variance increases, as some schools retain some elements of functionality while the worst become beyond bad.

The striking thing is that not only are government schools rent extracting, or paying more for inputs and teacher wages than needed, they appear to be actually value subtracting: a teacher in the government system does absolutely worse at producing child learning than a teacher completely on his or her own. The learning gains from moving children from organized public schools to completely unorganized, mom-and-pop private schools are roughly the equivalent of two full years of schooling. And these gains are cheaper than free. If there are roughly 12 million children enrolled in government schools, then these learning gains would save $200 million a year. Government schools, with hearty bureaucracies and much more means to attract qualified teachers, produce worse results than teachers just setting up their own schools.

Value-Subtracting School Systems in Uttar Pradesh

Uttar Pradesh is a populous state in northern India (with nearly 200 million people, it would be the world's fifth largest country). As the state has been expanding schooling rapidly, it has been hiring both regular civil service and contract teachers. Contract teachers are usually granted one-year contracts, subject to renewal. These contract teachers have, on average, less formal education and less pre-service training than civil service teachers, are not hired through standard civil service procedures (they are instead hired at the school or village level), are more likely to come from the villages in which they are teaching, and are generally paid less than civil service teachers. In 2009, civil service teachers were making around 11,000 rupees a month, compared to contract teachers at 3,000 rupees a month.

Recent research (Atherton and Kingdon 2010) used unusually detailed data on learning conditions and teaching practices to investigate the relative performance of contract teachers versus civil service teachers. The authors compared the learning of students who had contract teachers with that of children who had civil service teachers, controlling statistically for all other factors that affect student learning, such that their estimates are plausibly the causal impact of an equivalent student being randomly assigned a contract teacher versus civil service teacher. Atherton and Kingdon (2010) found that students taught by contract teachers learned twice as much per year of schooling as students taught by civil service teachers. Going from second to fourth grade with a contract teacher versus a regular teacher added about 0.4 effect sizes of learning (if linear, about 0.2 effect sizes of learning per year). The typical year in schooling with a civil service teacher produced total learning of about 0.2 effect sizes. So the learning impact of having a contract teacher versus a civil service teacher added about 0.2 effect sizes of learning, equivalent to an entire additional year of schooling.

The learning and cost implications of these findings are staggering. Suppose that Uttar Pradesh could replace all civil-service teachers with non-civil service teachers at the same cost and effectiveness of current contract teachers. If feasible, this act alone would double student learning—which is larger than the promise of any combination of expensive, cost-raising, EMIS-visible input increases—and would put Uttar Pradesh on par with the best-performing Indian states. Using illustrative numbers,2 in 2009 there were roughly 600,000 primary and upper primary grade teachers. The annual wage difference between civil service and contract teachers was U.S. $2,100 (11,000 rupees less 3,000 rupees times twelve months, divided by an exchange rate of 45 rupees per U.S. dollar), which I round to $2,000 a month. The annual cost savings would be $1.2 billion, or $30 per household per year in Uttar Pradesh (which is 3 percent of the average Uttar Pradesh household's total income). In fact, the wage premium—the excess that civil service teachers were paid over what teachers doing a better job were paid in 2009—was ten times the total expenditure of the median rural household in Uttar Pradesh.

If teachers were doing the same work but for more money or less work for the same money, then this evidence would be just another example of a common phenomenon (in both public and distorted private markets) of rent extraction. But this evidence suggests that the government organization of schooling in Uttar Pradesh is value subtracting. The expectation is that the education institutions, through teacher training, peer coaching, mentoring, providing teaching resources, and so forth, allow individuals to reach higher potential as teachers than they could independently. Yet a person with lower credentials and operating with little to no institutional support does an absolutely better job teaching students at lower cost if not hired into the civil service. Is it that the array of departments, councils, and bureaucracies, whose nominal purpose is to promote education, is actually doing the opposite? The evidence suggests that indeed these government schooling organizations are deeply antiteacher—people working there are worse teachers than they would be if they set out to teach the same students independently.

Highlighting the terrible performance of Uttar Pradesh's civil service teachers is not antiteacher. It is the government institutions of education that are antiteacher and antiteaching, on several levels.

One major problem is that the system does not enforce compliance even on fundamentals. As the comedian Woody Allen points out, 80 percent of success is just showing up. Yet teachers don't even do that. The UN's 1996 Public Report on Basic Education in India, better known as the PROBE report, whose senior researcher was Jean Dreze, documented the shocking state of elementary education, including lack of facilities, low enrollments, high dropout rates, and high levels of teacher absence in several weaker-performing states in North India (UNDP 1998). In part because of the report, teacher attendance garnered widespread, high-level attention and political concern from the left, middle, and right of the political spectrum.3 The PROBE team returned to the field in 2006, a decade after the original fieldwork had been conducted. During the course of this decade the government had made massive investments in schooling and focused attention on reducing teacher absenteeism. The follow-up study found significant improvements in EMIS-visible inputs: more classrooms, more desks, more teachers, more kids in school. But the teacher attendance rate was roughly the same as ten years before, a fact that has been documented by every independent study of actual teacher attendance since 1996.4 Absence rates of 25 percent that persist for a decade or more suggest not a crisis (which would imply some urgency for action) but rather a system that is comfortable with dysfunction.5

And it gets worse. Data from the 2005 India Human Development Survey (Desai et al. 2008) show that 29 percent of parents reported their child was “beaten or pinched” in government schools in the previous month. Worse still, this abuse in government schools discriminated against the poor. A child from a poor household was almost twice as likely to have been “beaten or pinched” as a child from a rich household. (Private schools, by contrast, while still using physical abuse as discipline, at least show no income favoritism in beatings, which is thanking heaven for small favors.)

Shockingly, the public system in Uttar Pradesh is producing a schooling experience of such low quality that half of urban parents do not send their children there even though it would cost them nothing, choosing instead to pay out of their own scarce resources for private schools. Even in rural Uttar Pradesh, one of the poorest places in India, ASER 2011 data showed that 45.4 percent of all rural children ages six to fourteen were enrolled in private school, compared to 46 percent in government schools (ASER 2012). Parents are using extremely scarce resources (57 percent of the average rural household's budget in Uttar Pradesh goes to food) to avoid government schools.

This government apparatus for schooling in Uttar Pradesh is an example of a value-subtracting organization. Teachers do an absolutely worse job when inside the organization than what they could do just working alone. The whole is well less than the sum of the parts.

The hard question is, how do public sector institutions and organizations survive with such dysfunctional performance? How do they maintain their legitimacy as organizations when they are not just ineffective and rent extracting but apparently value subtracting? And amazingly, despite its dysfunction, public education is not just surviving but in some ways thriving. During the decade from 1996 to 2006, real per student spending on government primary education in Uttar Pradesh more than doubled, and the centrally sponsored scheme to improve basic education was widely hailed both within India and by external agents as a success.

These two examples are just examples, not evidence that governments always, or even typically, fail. But these examples raise questions about failure. What happens in response to failure? How do failing schooling organizations and systems persist?

Isomorphic Mimicry: Camouflage for Failing Spider Systems of Education

An ant colony is a social world with an emergent order. Different ants play different roles in the social order, and they do so by following very simple biochemical scripts. This differentiation allows ant colonies to be tremendously successful in evolutionary terms, as the colony can act in complex ways even in the absence of a centralized intelligence directing each ant. However, natural evolution produces survival, which sometimes comes with what we regard as amazing features, such as the cheetah's speed or the eagle's eye, but it also produces bizarre behaviors. As Holldobler and Wilson (1990) recount, one species of beetle has evolved to emit the right chemical marker that makes worker ants believe that the beetle is actually an ant larva needing to be fed. So the worker ants will drag the beetle into the ant colony and feed the beetle as long as it continues to emit the right chemical signals. This happens even though the beetle looks nothing like ant larvae—the beetle is many times the size of an ant larva. The simple chemical mimicry of the beetle keeps the ants busy feeding a worthless beetle lout because they are following some simple preprogrammed scripts, and no individual ant is equipped to step back and say, “Hey, that doesn't even look like one of us. Why are we feeding it?”

If an ecosystem is configured so that parasites will survive, then parasites will emerge. The pressures of survival and evolution produce both thriving species and parasites thriving on those species. One species of fungus has evolved to take over an ant's body, including using mind control to cause the ant to become a zombie that serves as a vehicle for the survival of the fungus—with the ant killing itself in the process.

Given the deficiencies in learning and school systems outlined so far, one might hope that natural pressures on organizations would lead to improvements. The natural world's evolution metaphor, that weaker species die off and are “naturally” replaced by those better adapted to excel in an environment, suggests that low-performing organizations would die off and be replaced by high performers. Similarly, business market metaphors, or even political or policy metaphors for good ideas, suggest that weak organizations would die off and reform pressures would produce better outcomes.

But this hasn't always happened. In many countries, we observe persistently bad organizational performance, yet no discernible trend for the better. In fact, as we saw in chapters 2 and 3, the empirical learning profile has become worse over time in some countries, has stagnated in others, and has improved in only a few.

The deep question is, what is it about the ecosystem for basic schooling that allows the persistence of organizations that produce disastrously bad learning? How do ministries of education manage to maintain legitimacy and attract continued internal and external resources, despite continued failure?

My argument is that the key to this perverse success of failure in educational systems is isomorphic mimicry. Just as the beetle benefits from the ants by mimicking their larvae, failing public systems survive, and even thrive and attract more resources, by striving simply to look like functional school systems.

Ecosystems That Lack Evidence-Based Decisionmaking Encourage Camouflage

In a highly influential work on the behavior of organizations, the sociologists Paul J. DiMaggio and Walter W. Powell (1983) identified isomorphism as an organizational strategy. They argued that organizations often adopt “reforms” that have little or no demonstrated connection to the organization's goals but rather serve to provide the organization with legitimacy from key stakeholders, and with that legitimacy, increased support and resources. These actions do not touch the core of the organization but rather deal with peripheral functions in the organization.

Knowing that organizations engage in isomorphic mimicry leads to the question: What are the system conditions in which isomorphic mimicry is an attractive or even optimal organizational strategy? In what man-made ecosystems does organizational isomorphic mimicry thrive?

The schematic in figure 4-1 shows the characteristics of ecosystems for organizations and how those affect the strategies of organizations and agents in the ecosystem (Andrews, Pritchett, and Woolcock 2012; Pritchett, Woolcock, and Andrews 2012). Drawing on the work of Carlile and Lakhani (2011), this figure highlights two key features of an ecosystem of organizations: the space for novelty, and how novelty is evaluated.6

The space for novelty in figure 4-1 ranges from open to closed. How easy is it to attract the resources to do something innovative, particularly something with the potential to scale up? Some systems make it easy for new entrants to come in and try, while others have barriers—legal, social, political, operational—to entry.

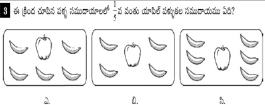

Figure 4-1. System characteristics determine the possibilities for failing organizations to persist through isomorphic mimicry.

Source: Adapted from Andrews, Pritchett, and Woolcock (2012).

The evaluation of novelty ranges from agenda confirmation to demonstrated functional success. Often innovations are simply new ways of doing the same thing and pose no threat to the core of the system. For instance, if in-service teacher training is done once a year, then someone could propose doing it twice a year. Or the content of teacher training could be altered to cover new subjects. Or teacher training could be done with active versus passive pedagogical techniques. In most educational system these “novelties” will be adopted, or not, for reasons unrelated to whether they lead to higher or lower student learning. An alternative way to evaluate a novel approach would be evaluate it based on functional success.

The basics of any evolutionary ecosystem, whether natural or man-made, are two features: a source of variation and a survival function for variation (see table 4-1). These combine to produce the dynamics of an evolutionary system. With no source of variation, there can be no dynamics. But variation alone is not necessarily a good thing. Nearly all genetic mutations are harmful, so variation without a survival function that differentiated on some criteria generates only observed variation, but no progress.

Table 4-1. Combinations of “space for” and “evaluation of” novelty (new ideas, innovations) make up the ecosystem for innovations.

When an organization, such as a Ministry of Education, is embedded in an ecosystem that both is closed—so that the organization is never under serious existential threat from a competitor—and does not have its performance evaluated according to any agreed-upon outcome metric of success but rather on “compliance,” then progress is doubly hard. Isomorphic mimicry can easily become the most desirable strategy. After all, organizational learning is hard even in the best of circumstances, when performance metrics are clear and pressure is on. When innovations are threatening to the status quo and meet strong internal and external resistance, and there is little or no consensus about their payoff, then avoiding hard changes while pursuing simple, cosmetically attractive, camouflaged objectives is a compelling approach.

This camouflage gives rise to an intellectual atmosphere in which creating functional standards and expectations for child learning is regarded as retrogressive and anti-education. In one of the saddest ironies of our era, the systems around “basic education” are ignorant of their own impacts. Without standards, there can be no measurement, and without measurement, there is no evaluation of success and failure. Luis Crouch's description of the predicament of the educational system in Peru, as he found it in 2006, is perfect, and poignant (see World Bank 2007).

The need to create standards is related to the need for developing a culture of evaluation in Peru. There is currently a pervasive fear in Peru's education sector of anyone being evaluated. This creates a vicious cycle. The fear of failure creates a fear of evaluation, but the lack of evaluation condemns almost all efforts to failure, because there is no serious way to detect when anything is going wrong. Failure and lack of evaluation against any kind of standard become self-fulfilling prophecies of each other, and create an environment of intense pessimism, fatalism, and lack of accountability. The fear of evaluation and standards has been turned into a virtue, and it has become popular to question evaluation and measurement as intellectually suspect, non-modern, regressive, or inequality-inducing.

Saying that educational systems are anti-evaluation is not synonymous with anti-novelty—quite the contrary. If you criticize any education system in the world, you will quickly be pointed to how they are changing and improving. Often this evidence will be data on the expansion of EMIS-visible inputs, but there will also be pedagogical and organizational innovations. But if you ask for evidence that these innovations are successful, you will be accused of not understanding how complex educational processes are and of pushing narrow criteria of standardized testing that would reduce the quality of the “true” educational experience.

The problem is not the lack of change or innovation but how the innovations are chosen, evaluated, and scaled. Innovations that reinforce existing agendas are always welcome. Moreover, every innovation can be successful if each is allowed to declare the performance against which it will be evaluated as an innovation. Circularity abounds, as mere adoption of the innovation is itself defined as success.

My argument is that a huge amount of what passes for improving the quality of schooling and even education reform is window dressing. Such reforms have no plausible evidentiary basis and do not include a plan for generating evidence about performance. The real purpose of reform efforts is to create certain appearances to legitimate failing and flailing systems, without making demands or threatening existing political interests.

The camouflage of reform has only gradually been revealed because many conventional schooling innovations were functional for the goal of schooling: getting children into seats (for example, building more schools, providing basic inputs, and hiring minimally equipped teachers). Whatever quality agenda existed also confirmed the schooling movement agenda and found ready acceptance and adoption, without any requirement for evidence. Whatever challenged the “more is better” belief system had a difficult time penetrating the closed space for public funding (which still dominates) and had to push uphill against existing incumbents, because there was no consensus view on the desired educational outcomes that would allow innovators to prove success.

The concern with innovation goes beyond organizations, as systems can produce scaled innovations as an outcome of a system in which no individual organization learns. In nature, the average fitness of organism in an ecosystem might improve even if no single organism learns, so long as organisms that better fit the ecosystem are more successful in reproducing. Thus, there is an important distinction to draw between organizational learning and ecological learning within a system. When productivity in a sector goes up over time, this is measured as the average productivity of all existing firms weighted by their size. Productivity could go up because existing firms get more productive (organizational learning) or because new firms that are more productive enter the sector and get bigger and bigger (ecological learning), or some combination of both. Economists often refer to ecological learning as “creative destruction,” after the economist Joseph Schumpeter, who emphasized that the success of capitalism was due to both the birth and the death of firms, as often new ideas are incompatible with the structures of old firms, so that new ideas lead to the shrinking and even disappearance of firms that are unable to adapt.

In market economies, there are sectors that illustrate both organizational and ecological learning. For instance, in retailing there have been several waves of creative destruction as new technologies made possible new ways of retailing. In the United States, for instance, the rise of low-cost train and truck transport and reliable nationwide mail delivery systems led to the rise of the firm Sears, Roebuck. This mail-order retailer blew gales of creative destruction across America as mom-and-pop retailers could not compete with the ability of people to order the latest of everything, from fashion to tools, straight from a catalogue. Sears became a huge firm that moved markets and was headquartered in the Sears Tower, at the time the world's tallest building. Leading business schools studied cases describing the keys to Sears's fantastic success.

No reader younger than I (fifty-four in 2013) can remember when Sears was a powerhouse, because, as recounted in Donald Katz's gripping account, The Big Store (1987), in the mid-1980s low-cost retailers eroded Sears's advantages. Of course, the company responded in various ways, but organizational learning is difficult even in high-pressure market environments, and Sears began a slide as a retailing organization. Lower-cost retailers such as Kmart that weakened Sears were themselves eventually confronted by new competitors like Wal-Mart, which has grown to over two million employees. (In a borderline ironic development, Kmart emerged from bankruptcy and bought Sears.) But these retailers are in turn under threat from both specialty superstores and online retailers such as Amazon.com. Retail marketing has gone through several generations of innovation now, and productivity is much higher. This is ecological learning. But the e-tailing world is dominated by Amazon.com and not Sears.com or Kmart.com or even Walmart.com because ecological learning can happen even when organizational learning is hard. This is particularly true when the innovation that is needed is inconsistent with the existing organizational culture and requires “disruption.”

What is the point of a vignette about American retailing in a book about education in poor countries? The gains in productivity in American retailing did not come about through the application of strategies thought up by the best and brightest managers in the best and biggest companies. Rather, productivity gains were the result of an ecosystem in which consumers could vote with their feet, creating a functional evaluation of innovations and a market system in which new entrants could attract resources to expand. The system produced the result through ecological learning, not the learning in the organizations.

Weak Systems of Accountability Produce Isomorphic Mimicry by Organizations and Agents

Whenever a tire is flat, the flatness is manifested at the bottom of the tire. But the hole isn't always at the bottom. In education, the evidence about teacher and student performance is generated at the school level. The temptation is to blame the teachers or school-level factors for inefficiencies or poor performance. However, in a system of accountability, the problems that are visible at the school level may have causes that are far removed. It is easy to say, “Children are learning so little because teachers are absent.” And since teachers are the agents choosing not to attend or not to exert effort, it is easy to pin the blame on teachers. However, teachers are often themselves trapped in systems designed to induce and encourage bad outcomes. For instance, in political systems driven by patronage, in which politicians are rewarded for giving teaching posts to supporters rather than providing better education, the insulation of schools and teachers from performance responsibility is not a flaw but woven into the design. In education bureaucracies that rely on top-down control of rules and procedures, even positive deviations are squelched, not rewarded.

To switch metaphors, if your electric toaster does not work, your bread does not get toasted. However, without further investigation, it is impossible to tell whether the toaster doesn't work because a wire inside the device is broken, there is a fault in the wiring going to the outlet inside your house, the power is out in your entire neighborhood, or there is a regional blackout. If the power is out citywide, then trying to fix your toaster because your toast doesn't brown does no good at all. Moreover, there could be multiple failings, and every fault in the critical path has to be fixed for the toaster to work—the power has to make it to your house, the house wiring has to get power to the outlet, and the toaster has to be plugged in, and a heating device has to turn power into heat (and turn off).

The problem with government schooling is not that it is government schooling, it is the governance of schooling. The best systems of basic education in the world are predominantly government systems. Moreover, countries with predominantly publicly financed and controlled systems of schooling have discovered many different ways to be successful. Germany, France, and the Netherlands each have systems of basic education that produce (near) universal completion and high levels of learning, but they operate under fundamentally different institutions of governance. But what high-performing, publicly produced education needs is a coherent system of accountability, which can be embodied in many different institutional arrangements.

The World Bank's 2004 World Development Report, Making Services Work for the Poor, created an overarching framework for analyzing systems of accountability.7 I cannot hope to do justice with a summary of that report, but want to draw on a few details using that framework. The report argued that a coherent system of accountability for the governance of schooling is one in which three functional relationships of accountability, namely, politics and voice, compact, and management, and the four design elements of any relationship of accountability, namely, finance, delegation, information, and enforceability, work together.

Table 4-2. Performance accountability in “long-route” systems for the public production of schooling can go wrong in many ways.

For governments to drive the traditional “long route” of public sector production of schooling to success, they have to create conditions in which all the relationships of accountability work, at least tolerably well, in each of the elements of accountability (this is called the “long route” precisely because it involves multiple different accountability links to work). Table 4-2 lays out the many ways in which the traditional long-route accountability approaches go wrong in centralized spider systems in developing countries.

Accountability is a system property. Strong accountability requires the integration of each of the design elements. Unfortunately, facile advocacy seizes on one element of the problem, with proponents then declaring they have found the elixir. For instance, many focus just on the element of enforceability, and claim the source of weak accountability is that you cannot do anything about poorly performing teachers. As this simplistic reasoning goes, if you could only fire at least some bad teachers, then all teachers would get the message and improve their performance. In this view, the villain is often the teachers’ union, which blocks performance accountability for teachers.

This logic might get it exactly backward. There is no successful educational system anywhere, of any kind, that attained excellence by being hostile to teachers. Moreover, reducing the accountability of teachers to prescribed Taylorist controlled work environments and procedures as a way to hold them accountable is inconsistent with the nature of teaching as an intrinsically creative activity. Teachers’ unions and their behavior are the result, not the cause, of spider educational systems. That is, the top-down, public production systems turn the craft and profession of teaching into a cog in a bureaucracy. If there is only one, monopoly financer of education, then teachers are at the mercy of that organization. If this organization treats teachers like automatons who are expected simply to follow rules, overly structures their work environment, and does not create a positive sense of teaching as a vocation with learning as the goal, then naturally teachers will respond by creating countervailing pressures through their own political organization.

Alternatively, suppose that these advocates triumphed and the system could fire teachers (or there were stronger “enforceability” as an accountability design element in the “management” accountability relationship between organizations and front-line workers), but the overall system of accountability were deficient in its other components—like “delegation” and “information”? Well, first of all, whom would you fire? Obviously, low performers. But when the delegation relationship is weak, so that teachers are overburdened with too many vague goals and given no support in achieving those goals, termination is manifestly unfair. Moreover, since delegation is weak, there is little or no reliable information on which specific teachers are or are not contributing to achieving education goals. Allowing organizations to fire teachers may result in completely arbitrary decisions, as teachers who are unorthodox in their approach but successful get fired for noncompliance with processes and procedures unrelated to actual goals. Worse, without the constraints of clear delegation and reliable information, imposing more enforceability on teachers may lead to good teachers being laid off just so that they can be replaced with a local patronage hire. So the very civil service protections that now thwart accountability were once seen as huge gains to prevent abuse.

The point is, you cannot fix organizations or expect very different behaviors from front-line agents unless you fix the system. That this is a system problem is too bad, because none of us are very good at thinking about system problems. Most of us are experts (of a sort, at least) at thinking about objects and agents because we need to be experts at objects and agents just to get by with life. None of us can be very successful at life without having pretty good theories about how objects—bricks, tables, shirts, pots and pans—will behave. We know what is solid (bricks) and what isn't (water), and we hence know that kicking a brick will hurt more than kicking water. Similarly, none of us can be very successful at life without having pretty good theories about how other agents (especially people) will behave. We have pretty good ideas about what noises will get another agent to pass us the salt, what actions will make people angry, and what will make people happy. These are incredibly sophisticated mental feats for which billions of years of evolution have equipped us, and hence as humans we operate pretty well our whole lives with the dualistic mental ontology of stuff and agents we master by the time we are two-year-olds.

In contrast, most of us are completely worthless at thinking about system problems, because we almost never need to. In Howard Gardener's (1991) evocative phrase, we live with an “unschooled mind” about systems. People live in incredibly sophisticated modern economies and have absolutely no idea how they work. And that is mostly OK, because the beauty of emergent orders in self-organizing systems is that no individual agent has to understand how the whole system works in order for the whole system to work (Seabright 2010). The problem is that when people do think about systems, they tend to extrapolate their expertise in objects and agents. In other words, they tend to anthropomorphize and tell narratives and reason about systems as if a system were an agent.

But in complex adaptive emergent orders the system can have outcomes that no agent in the system intended. Two examples of complex adaptive systems in which outcomes emerge are evolution and economics.

If one asks questions today about the natural world, such as why an elephant has a long trunk, the answer will be that it is the result of evolutionary processes. This is a shorthand way of describing a system in which there is (1) a source of variation and (2) a mechanism that essentially evaluates variation, in that some variants are more like to replicate than other variants. No central planner ever designed an elephant's trunk based on its optimality criteria. No elephant ever chose its trunk size. The explanation for the wonders of the animal kingdom is that things just happened that way: stuff at the basic biological level (such as genes) interacted with system constraints, and the outcome was an elephant's trunk.

The essential insight of economics is perhaps still best expressed by two passages from Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations (1776):

Give me that which I want, and you shall have this which you want, is the meaning of every such offer; and it is in this manner that we obtain from one another the far greater part of those good offices which we stand in need of. It is not from the benevolence of the butcher[,] the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.

As every individual, therefore, endeavours as much as he can both to employ his capital in the support of domestic industry, and so to direct that industry that its produce may be of the greatest value; every individual necessarily labours to render the annual revenue of the society as great as he can. He generally, indeed, neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it. By preferring the support of domestic to that of foreign industry, he intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for the society that it was no part of it. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it.

When this is simplified into mathematics, economists can show that some equilibrium allocations have a property called “Pareto optimality” (after an Italian named Vilfredo Pareto), which is that the allocation is “efficient” in the sense that there is no other allocation of consumption or goods that makes everyone better off without making someone else worse off. The most important point is not defending markets in the real world but the deep conceptual point that one can formally model complex adaptive system and show that the system has properties, desirable properties in the this case, that no agent in the system intended or sought. This is an emergent property of the system itself and cannot be explained in baby ontology categories of why things happen.

I am going on at length about this because this book is about explaining and fixing poor learning outcomes by fixing broken systems, not fixing people. But I have to go on about this because system explanations just have no appeal to people, myself included. Agent-centered explanations are powerfully appealing to us, on a very deep level. Believe me, if your child says, “Daddy, tell me a story,” you can be sure he or she wants a story with agents, heroes and villains who have goals and make plans and overcome obstacles. Even economists when they try to explain Pareto optimality resort to making the ontological unfamiliar seem plausible by invoking “an invisible hand”—and hence making it seem familiar. “Oh,” say sophomores on hearing the invisible hand metaphor, “like an agent with a hand willed it. Now I get it”—and hence deeply don't get it. But even as an economist who loves system explanations in the domain of my expertise, I am bored silly by historians who tell the stories of structures and institutions and geographic constraints (I have never been able to make my way through any small part of the French historian Braudel, for instance, though I often think that I should). I love a good yarn about American independence that does not involve the carrying trade but does involve George Washington and his bravery. The appeal of agent-centered, human narrative explanations over systemic explanations is why no one—except perhaps you—is reading this book.

This is because nearly all of our success as organisms is driven by understanding stuff and agents. Just as none of us really needs to understand quantum mechanics or general relativity to live our whole lives as successful, fulfilled, productive individuals, the number of times any of us needs to understand systems is vanishingly small. You can have a successful professional career without understanding systems. You can have a happy marriage without understanding systems (perhaps more likely, in fact: try asking your spouse sometime about the system of marriage—such as “Why did monogamy as an organizational form of the family triumph over polygamy?”—and see how that works for you). You can raise lovely children without understanding systems.

You just never need to really understand systems, until you do. Because even though life is always really about agents, it is also really always about systems.

Dangers of Isomorphism I: Good Ideas Can't Succeed in a Camouflage System

The first danger of isomorphic mimicry in spider school systems with weak accountability is that good ideas imported from elsewhere become irrelevant or even bad ideas, as they are used to prevent needed system reforms. Implementing “best practice” gleaned from the superficial comparisons of the forms of schooling around the world can even lead to perversity, and “best practice” can make things worse if form and function have diverged.

What passes for advice is looking at the success of the Finnish schools and recommending to others, “Do what the Finns did.” The reality is that what countries need to do is not what the Finns did but rather they need to do what the Finns did. Yes, I know, sorry about that sentence; I'll try again. What countries need to do is not what the Finns did; rather, they need to achieve what the Finns achieved—which might require doing the opposite of what the Finns did. That is, the problem is not adopting the forms of what the Finns did but rather solving the problems the Finns solved to produce functionality—which is what the Finns did—but that approach may not at all produce the same forms the Finns ended up with.

Camouflage Protecting Organizations Rotten at Their Core

Students of organizations traditionally identify five elements of organizational structure (e.g., Mintzberg 1979). One is the technical or operational core, which is where the value added of the organization happens. For a manufacturing firm, this would be the factory floor; for a hospital, it would be the care provider-patient interactions. Around the technical core are other elements of the organization: top management, middle management, technical support, and administrative support. Ideally, in a schooling organization or system, the technical core would be the classroom interactions between teachers and learners (and among the student learners themselves). The rest of the organization would include technical support for training and supervision, administrative support for procuring materials, and the human resource functions of hiring and allocating teachers, as well as middle management and top management. These components would provide support to those in the technical core (teachers) to improve their productivity in educating children.

How do we explain the survival of organizations like school systems that are value subtracting (or even ineffective or rent extracting)? How can an organization be sustained if teachers, part of the organization's core, are less productive at achieving learning goals inside the organization than if they were to have no association with the school system? If organizations survive, it is because they create value for someone, and hence the question is, what is the real operational core of dysfunctional schooling systems?

Moreover, what happens to the human resource functions of recruiting, hiring, and assigning teachers to classrooms in value-subtracting school systems? In a functional schooling system, these are “support” or administrative functions that contribute to the operational core by making sure that each classroom has a teacher with the capacity to help students learn—the value-creation function of the organization.

At their worst, the only value schooling systems create is contracts for school builders and jobs for those hired. In a dysfunctional system, hiring and allocating people to civil service protected posts becomes the rotten technical core of a rent-extracting—and even value-subtracting relative to its putative purpose—organization. The people who control the allocation of those jobs (including hiring and assignment) are afforded a lot of power and value. Imagine that I get to hire teachers who are paid 20,000 rupees a month, but many people with the same qualifications would take up an equivalent teaching job at equivalent quality for 2,000 rupees a month. I am controlling 18,000 rupees per month of potentially extractable rents.

The problem then becomes that the perversion of purpose of the school system—rent extraction—is camouflaged by the pretense that it is really creating learning. It is essential that it go through the motions so that it looks like an educational organization, even though it really isn't an organization about education at all.

Central to this camouflage is the resistance to changes in the ecosystem that would reveal the true technical core of the organization (rent extraction). Therefore it is essential that outcomes—actual student learning—not be measured in a repeated, regular, and reliable way that would allow easy comparisons of the value added of the organization with other alternatives. It is also essential that innovations be contained strictly within the organization so that the space for novelty (especially novelty that receives public support) is limited.

Input Improvements as Camouflage Do No Good—and Protect Harm

The danger of isomorphic mimicry is that elements that really are part of a successful education system are used tactically by dysfunctional systems as camouflage. Education initiatives that really can improve student learning are copied and implemented in such a way that they do not have any impact on learning and instead protect and further the noneducational objectives of the dysfunctional organization. Here are three examples of improvements that work in functional systems yet don't work in isomorphic mimicry systems.

Smaller Class Sizes

There is no question that reductions in class size can improve student learning. At the extreme, one-on-one or one-to-few tutoring is widely regarded as an ideal learning situation (as evidenced by its use to educate elites for millennia prior to mass schooling). There is also no question that reductions in class size alone, when implemented with no other changes to systems or accountability, might not result in learning gains. And now there is no reasonable doubt that class size reductions alone in some situations do not work because the huge literature on the topic, with debatable internal validity due to nonexperimental data, has been added to by rigorous randomized experiments.

For example, a recent experiment in Kenya, carried out by researchers from Harvard and MIT, featured the government randomly granting permission to some schools (or rather their parent-teacher committees) to hire an additional teacher, reducing class size—often from very high levels of one hundred or more students per class. Students in schools receiving a contract teacher were randomly assigned to the contract teacher or a civil service teacher. The new contract teacher's salary was one-fourth that of the civil service teacher's and the contract teacher's contract was subject to school committee renewal, while the civil service teacher had the normal civil service protections. As shown in figure 4-2, students gained 0.13 effect sizes more in learning in both math and literacy if they were assigned to a contract teacher in a school with school-based management improvements. On the other hand, if they were in a class of reduced size with a civil service teacher the students got absolutely no benefit from that (Duflo, Dupas, and Kremer 2012).

The mechanism of the differential impact on learning of contract teachers versus civil service teachers is not difficult to discern. The civil service teachers reduced their attendance as a result of having a contract teacher assigned to their school. Just as in the story of the gardener above, once there was more help, the civil service teachers did not utilize the additional help to improve performance but rather used it to do less work.

Figure 4-2. In Kenya, reducing class size with contract teachers, but not with civil service teachers, produced gains.

Source: Adapted from Duflo, Dupas, and Kremer (2012).

The idea behind using solid research methods (such as randomization) is to prove what works so that these new ideas can be scaled up. What is interesting is that this study (the results of which were available in roughly their current form in 2007) has produced two additional actions, both of which illustrate the dangers of isomorphic mimicry.

First, researchers tried to replicate the findings that additional contract teachers would improve student test scores at a larger scale than the original study (Bold et al. 2013). In doing so they replicated the process using both the Kenyan Ministry of Education and an international NGO, World Vision. Bold and colleagues found that when the original policy of contract teachers was implemented by the NGO, it had exactly the same impact, with relatively big effect size learning gains for students exposed to contract teachers. But when the Ministry of Education was responsible for implementation, even of the same design and using contract teachers, the impact on student learning was zero. So the Ministry appeared to be adopting a best practice of policies that had been “proven” by “rigorous research” to work, but it did not have the same impact.

Second, given the long lag of busy researchers in producing papers, one can see isomorphic mimicry play out in real time. Duflo, Dupas, and Kremer (2012) conclude their report with the following statement:

Subsequent to our study, the Kenyan government, which had long had a freeze on hiring of new civil-service teachers, hired 18,000 contract teachers. Initial plans included no guarantee of civil-service employment afterwards. However, the Kenyan National Union of Teachers opposed the initial plans and under the eventual agreement, contract teachers were hired at much higher salaries than in the program we study, hiring was done under civil-service rules heavily weighting the cohort in which applicants graduated from teacher training college rather than the judgment of local school committees, and contract teachers hired under the program were promised civil service positions.

So all the key features of the contract teachers program that were “proven” to work were undermined politically and organizationally by pressures of isomorphism: formal training was valued over local judgment in hiring, civil service protections versus accountability for performance, and higher salaries over market-based wages.

The difficulty is that reductions in class size contribute more salaries for teachers—and hence to possible rent extraction by a rotten core—whether or not they contribute to learning. Both performance-driven and rent-driven systems will want to reduce class size at times, the former to improve learning and the latter to extract more rents, achieved under the camouflage of purported improved learning.

Teacher Training

An evaluation of decades of in-service teacher training in Indonesia found little or no impact on student learning, or even on teacher practices. How is it that this technical support, an element of any organization, has no impact on the performance in the technical core of the classroom? Because the technical core in dysfunctional systems is not supporting performance in the classroom but rather focusing on rent extraction. Close examination of most teacher training in Indonesia in the period under review found that the system was really designed to channel funds to teachers through excessive reimbursement of training costs rather than to provide training.

One anecdote from my experience living and working in Indonesia (which is dated and possibly not relevant to Indonesia today) illustrates three ways in which substantial budgets for training were used to extract rents. First, training sessions were usually three days, so that each participant received three days of per diem and two nights of accommodation. But the first day's training consisted of only one session, at night, and the third day's training consisted of only one session, in the morning, with just one full day of training in between, on the second day. Second, the hotel would give receipts for one rate but charge teachers another (with a kickback for the hotel) so that each night's accommodation was profit to the teachers (and the hotel owners). Third, often one teacher would attend and sign for other colleagues, so that one teacher attending one day of training would collect the per diem and accommodation fees for two or three colleagues. The administrative records of in-service training for an education project would show lots of budget spent, lots of man-days of training received, lots of curricula covered—but underneath, it was all a charade. The fact that empirical studies found no impact of this training should not have surprised anyone who knew the system. Teacher training could have impacts, but what happened in Indonesia was camouflage called teacher training.

Camouflage also plagues pre-service training. There is little empirical evidence of impact from pre-service training, even though subject matter knowledge and formal education tend to be associated with student learning. Does this mean pre-service training isn't important? No. It indicates that the pre-service training that exists is for the most part just isomorphic mimicry that looks like training.

Warwick and Reimers (1995) examined teacher training in Pakistan and found that all parties, trainers and trainees, were just going through the motions, and, not surprisingly, teacher training had no impact on student achievement. The authors’ review of two teacher training institutes concluded:

Most inmates of this system have no respect for themselves; hence they have no respect for others. They mock at the system, laugh at their own foibles. They don't trust each other. The teachers think the students are cheats, the students think the teachers have shattered their ideals. Most of them are disillusioned. They have no hopes, no aims, no ambitions. They are living from day to day, watching impersonally as the system crumbles around them. If there is a major cause of self-destruction, it is this: each lifts a finger to accuse the other. Everyone thinks of themselves as a victim.

Yet even in this condition, when this is the description of the system for training new teachers, experts recommend that more teachers need pre-service training. Why? Because everyone “knows” that good education systems have trained teachers, so the camouflage value of teacher training trumps over the reality.

Teacher Salaries

The dangerous thing about isomorphic mimicry is that by imitating functional systems with a patina of formal structures and rules, dysfunctional education systems look to naive outside experts as places to implement best practice. So international experts come with advice that works in functional systems that may backfire because piecemeal advice doesn't take into account how the entire system is wired.

Often, experts give advice by examining top performers and telling others, “Be like them.” For instance, a recent report aimed at improving teaching quality in the United States compared the United States to “high-performing” systems (Singapore, Korea, Finland) and found much greater fractions of teachers in those countries were in the top third academically. Thus the report recommended that the United States attract academic high performers into the teaching profession through better compensation, as is done in “high-performing” systems (Auguste, Kihn, and Miller 2010). In the end, no matter how subtle the original message and no matter how focused on just the United States, the take-away lesson is that higher teacher pay leads to better performance.8 This naturally strikes a welcome chord with key education constituencies. With such evidence, it becomes possible to treat raising teacher's salaries as not just politically expedient but actually best practice because it is what high-performing education systems do.

The easily recognizable problem is that systems operate as systems, and merely imitating one component of a system without the other components will not necessarily lead to the same outcome—in fact, it could make the outcome perverse. The organizational economist John Roberts (2004) emphasizes that compensation schemes are complementary with other dimensions of firm organization, and so introducing a bonus system within a firm may or may not increase worker productivity, depending on how the bonus interacts with other elements of the organization of production.

Here is the kicker about the Uttar Pradesh evidence that opened the chapter: despite the evidence that civil service teachers were massively overpaid relative to their contract teacher or private sector counterparts, and despite the evidence that, on average, students taught by civil service teachers versus contract or private teachers learned less, the pay of civil service teachers was raised. So while the study in 2009 found civil service teachers making almost four times the wage of contract teachers (which was itself higher than the private sector wages) of 11,000 rupees a month, the current average pay for civil service teachers is 23,000 rupees a month.

This high pay has led to perverse results: the appeal of the higher salary has made the demand for civil service teaching jobs so great that the profession attracts people who have no interest in teaching but rather join, often using bribery or political connections to do so, because of the high salary and low accountability. So the combination of (1) high pay with (2) systems that are ineffective at hiring the best teachers (as opposed to those with appropriate credentials and political connections) and with (3) systems with weak local accountability (which is exacerbated by hiring teachers more powerful than the village leaders in communities to which they are posted) leads to even worse problems. As I have argued elsewhere, this combination has led in India to a “perfect storm” in which costs are high, learning is low, students are unhappy, parents are unhappy (and moving to private schools), and teachers themselves are unhappy with their working conditions, despite the high pay (Murgai and Pritchett 2006).

And yet people use the evidence of best practice as an isomorphism to push for even higher salaries (and sometimes get them). Popular education reforms, even ones that are proven to work in some circumstances in which ecosystems create performance pressures, when implemented without consideration of the ecosystem of accountability and innovation will just fail.

Dangers of Isomorphism II: Resisting Disruptive Innovation

Animals go extinct not because their genes change but because their environment does. When the climate changes or when a new predator is introduced, survival requires animals to change or die. Mostly they die. The result of rapid environmental changes is usually not the learning of species but monumental declines in the population, or even extinction. This is because the stability of the genetic code, which is a boon in stable times, cannot change fast enough to adapt to changed conditions.

Spider education systems are both incapable of making the changes needed to pursue the learning agenda and block the viable space for innovation. The dysfunctional spider systems found in the developing world lack accountability structures that would allow them to respond effectively. The systems of education have created a cocoon in which isomorphic mimicry, which allows schools to look like good schools without being good schools, is a strategy that safely provides success at every level. Systems that promote isomorphic mimicry through a closed set of possible innovators (only the top) and through weak performance of innovations on the basis of demonstrated functionality effectively deflect disruptive innovation.

The second danger of isomorphic mimicry is that there is no room for the innovation or reform that leads to improved learning. Spider systems may have a constant stream of “innovation” and “reform,” but the system does not choose which “novelties” to scale based on their functional performance, nor does it have an effective mechanism for the diffusion and scaling of a novelty that has proved successful. The camouflage protects the organizations from failure and delegitimation, but at the cost of only being able to continue “business as usual.” Once the ecosystem is aligned into isomorphic mimicry mode, then even well-meaning leaders or bold outside reformers have a difficult time getting productive ideas up.

Even Innovative Leaders Can't Implement Innovation in Isomorphic Systems

Education system leaders can choose between activities that push the functionality of the organization and activities that promote the organization's narrower interests in perpetuation and expansion. In isomorphic systems, leaders who provide more of the same are lauded and rewarded. Expanding budgets, raising teacher salaries, hiring more teachers, and expanding enrollments are the outcomes that the system is set up to track and measure, and hence these are efforts that bring immediate rewards, even if they do not address any of the system's problems or improve outcomes in education or learning.

Improving organizations can be very painful, particularly in organizations in which norms of front-line workers are entrenched and expectations are low. Sustaining core reforms that change front-line worker behavior typically requires a strong political authorizing environment (e.g., Moore 1995) and at least a minimal inside coalition of support (e.g., Kelman 2005).

This is not to say there are no reforms—quite the opposite. A common complaint among teachers and principals is reform overload. Every few years a new fad comes along, and teachers are expected to adopt this new idea into their classroom practice. But in a closed system without the ability to differentiate functionally, these innovations do not necessarily improve outcomes. Innovative organizational leaders often get crushed because the existing system has no way of acknowledging success, even on the items already on the organization's agenda. Without some way of demonstrating success on established consensus goals, potentially successful reforms can get reversed under push-back from outside and inside before they have had time to take hold and establish themselves.

In a system with no consensus about standards of performance or rigorous, real-time measures of what would constitute demonstrated success, then the optimal organization strategy may well be business as usual in the core activities, even if they are dysfunctional, combined with isomorphic mimicry of best practice activities that do not threaten fundamentals on the surface as camouflage.

Effervescent Innovation: Challenges to Scaling in Isomorphic Systems

One of the most puzzling aspects of schooling is the magnitude of innovation. The field of education is always abuzz with the latest thing. The problem is that many ideas, including ideas with compelling evidence on their side, don't scale. If the survival function is not strongly related to performance, then in a closed system, these new ideas do not attract more resources and grow across schools.

Think about a glass of Coke as a metaphor invoking “effervescent innovation.” Pour out a glass of Coke and bubbles pop up off the surface. But, once poured, the level of Coke is at its maximum. The bubbles are a transitory phenomenon, rising and fizzling back to the initial beverage level.

You can travel to any country in the world and see educational innovation—someone can take you to a great school, or a great initiative. If you come back in five years and ask to see educational innovation, you will see it again—someone can take you to a great school, or a great initiative. Five more years, more good schools, more great innovations. But has any of this led to replicated changes at scale such that you can see more good schools, more great innovations, such that system productivity has increased? Have any of the bubbles risen beyond where the Coke was originally poured? Crouch and Healey (1997, 2) described this problem perfectly:

There is a particular irony to education reform. Pockets of good education practice (such as enlightened and effective classroom management, novel curricula, and innovative instructional technologies, many of them cost-effective) can be found almost anywhere, signifying that good education is not a matter of arcane knowledge. Be it the result of maverick teachers, the elite status of the parents, enlightened principals, and/or informed communities, these localized pockets of effective educational innovation can be found throughout the developing world, sometimes in poor material circumstances. Yet the rate of usage of the available knowledge, and the rate of spread of effective practices, is depressingly low. As a result, these innovations exist on a very small scale—the number of schools affected by these reformist innovations is minuscule relative to the total number of schools. Moreover, these innovations often have a short half-life. Either the maverick teacher leaves the system, the enlightened principal gets burned out, or the informed community simply loses interest after finding no echo of support in the bureaucracy.