One

DISPLACED

Sergio Vieira de Mello’s youth left him with the impression that politics disrupted lives more than it improved them. In March 1964, around the time of his sixteenth birthday, a group of military officers decided to unseat João Goulart, Brazil’s democratically elected president. Under Goulart the rural poor had begun seizing farmland, and the urban poor were staging food riots. The generals accused Goulart of allowing Communists to take over the country. Just five years after the Communist victory in Cuba, U.S. president Lyndon Johnson had similar concerns. The U.S. ambassador in Rio de Janeiro warned that if Washington did not act against Brazil’s “radical left revolutionaries,” the country could become “the China of the 1960s.”

1

In an operation code-named “Brother Sam,” four U.S. Navy oil tankers and one U.S. aircraft carrier sailed toward the Brazilian coast in case the generals needed help.

2

They didn’t. President Goulart had some support in the countryside, but much of the public had tired of him. On March 29 the front-page headline of the Rio newspaper

Correio da Manhã declared “ENOUGH!” The next day it proclaimed “OUT!”

3

A force of ten thousand mutinous Brazilian troops marched from the state of Minas Gerais toward Rio. Goulart ordered his infantry to suppress the revolt, but they chose instead to join the coup, and Goulart fled with his wife and two children to Uruguay.

Young Sergio was no more political than most teenagers. His focus was on keeping up with his studies (he would finish first in his high school class), following the Botafogo soccer team (which that year would share the prestigious Rio-São Paulo Championship), and chasing girls on the Ipanema beach, just two blocks from his home. But his relatives and schoolteachers had led him to believe that Communism would be bad for Brazil and the military could be trusted to restore order. Brazil’s generals had taken power in 1945, 1954, and 1961 and had ruled benignly and only briefly each time. Since the leaders of the coup promised to hold elections the following year, he joined his family and friends in initially cheering the military takeover.

“THEIR TRANQUILLITY HAS DISINTEGRATED”

Arnaldo Vieira de Mello, Sergio’s father, had grown up in a farming family in the agricultural hinterland of Bahia, Brazil’s northeastern province.

4

Arnaldo and his four siblings had been sent away to a Jesuit boarding school in Salvador, the province’s capital. After attending university in Rio, Arnaldo worked as an editor and war commentator at

A Noite (“The Night”), a leading newspaper at the time. He was determined to pass the entrance exams for the Brazilian foreign ministry, which he did in 1941. So poor that he could afford neither books nor notebooks, Arnaldo did all of his reading at the Rio public library, squeezing his notes onto the palm-sized forms used to order library books. He carried around plastic bags filled with stacks of such forms and arranged the bags by subject area.

In 1935 Arnaldo met Gilda Dos Santos, a seventeen-year-old Rio beauty. He quickly befriended her mother, Isabelle Dacosta Santos, an accomplished painter, and her father, Miguel Antonio Dos Santos, a man of many talents who was well known in Rio as a writer of musical theater, a French and German translator, and a poet who ran a jewelry store with his brothers. “Arnaldo is getting engaged to my father,” Gilda joked to friends. The young couple married in 1940 in Rio, and Gilda gave birth to a daughter, Sonia, in 1943 and then to Sergio on March 15, 1948.

The Vieira de Mellos lived a peripatetic existence typical of diplomatic families. In 1950 Arnaldo, then thirty-six, moved his wife and two children from Argentina, where young Sergio had spent his first two years, to Genoa, Italy. In 1952 Arnaldo was posted back to Brazil, where Sergio lived until he was nearly six. Arnaldo was next sent back to Italy to work at the consulate in Milan, where Sergio and Sonia were enrolled in the local French school. In 1956, the year of the Suez crisis, the family lived in Beirut, and in 1958 they finally settled in Rome, where they lived for four years, one of the longest consecutive stints Sergio would spend in a single city in his entire life.

Arnaldo Vieira de Mello was a charismatic and highly cultured man. “Audacity is the winner’s gift,” he liked to say, as he urged his son to be bold in his intellectual and personal pursuits. But his own career stalled, and he never earned the rank of ambassador. Frustrated by this professional plateau, he became an increasingly heavy scotch drinker. When he brought the family back to Rio in 1962, he became a regular on the trendy nightclub circuit there, keeping up with the current fashions and socializing late into the evenings. On the nights he stayed at home, he disappeared into his study, where he immersed himself in a world of books and maps. While he maintained his day job as a diplomat, he managed to write a history of nineteenth-century Brazilian foreign policy, which was published in 1963 and became part of the curriculum for aspiring Brazilian civil servants. He also embarked upon an ambitious history of Latin American navies.

5

It was Gilda who kept close

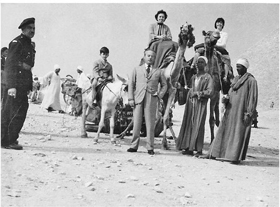

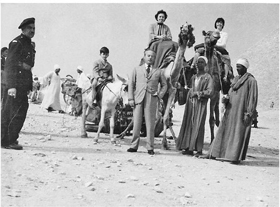

The Vieira de Mello family (left to right: Sergio, Arnaldo, Gilda, and Sonia) in Cairo, December 28, 1956.

watch on Sergio’s studies, promising to buy him gifts in return for high marks and taking him shopping the very day he received his grades.

When Arnaldo was assigned to the Brazilian consulate in Naples in late 1963, Gilda, who had learned to live a life that revolved around her children more than her husband, thought it best to remain in Brazil. Their daughter, Sonia, had gotten married and was expecting a child, while Sergio was attending the Franco-Brazilian lycée, a Rio school popular with the children of diplomats. Arnaldo was afraid of flying, and since the steamer from Europe took more than a week, he returned to Brazil just once a year.

The Brazilian military, which ended up running the country until 1985, would rule more mildly than other Latin American martial regimes. Still, the generals muzzled the press, suspended basic civil liberties, and ended up killing more than three thousand people.

6

The military’s reign was neither as benign nor as temporary as Brazilians had expected.

Some of the ruling generals proved especially ruthless. In 1965, the year after the coup, a group of hard-liners held sway. Sergio, who was by then seventeen, spent several afternoons each week volunteering at the Rio de Janeiro campaign headquarters of Carlos Lacerda, a charismatic local governor and anticorruption crusader who hoped to become Brazil’s president in the next election. But the generals turned on Lacerda, barring him from political office and dissolving all major political parties. Sergio’s uncle Tarcilo, Arnaldo’s youngest brother, was a brilliant congressman and orator who had gained fame as the leading proponent of legalizing divorce. As the generals tightened their grip, Tarcilo called on diverse political players, including Lacerda and the deposed president Goulart, to join forces in a Frente Ampla, or “Broad Front,” devoted to ending military rule and restoring democracy. But after he ran unsuccessfully for governor of Bahia in 1967, he dropped out of politics, and the generals maintained their grip on power.

7

Sergio had studied philosophy in high school, and in an essay in his final year, he reflected on the foundations of a just world, which, he argued, were rooted not in religious morality but in the “more objective notions of justice and respect.” International politics were no different from social intercourse, he wrote, in that the key to amicable ties was what he called “individual and collective self-esteem.” Only then could stability be built “on peace and understanding and not on terror.”

8

Later that year he enrolled in the philosophy faculty at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, which was plagued by teacher strikes. After one frustrating semester in the classroom, he asked his father, who had left Naples and become Brazil’s consul-general in Stuttgart, Germany, if he could travel to Europe for a proper university education. Arnaldo granted his son’s request, and Gilda traveled by ship with Sergio across the Atlantic in order to help him get settled. In Switzerland he met up with Flavio da Silveira, a Brazilian friend from childhood whose family lived in Geneva. The two friends enrolled at the University of Fribourg, in the picturesque medieval town an hour’s drive from Geneva. They spent a year studying the writings of Sartre, Camus, Aristotle, and Kant, with a faculty composed largely of Dominican priests. Their appetites whetted, they applied for admission to the Sorbonne in Paris. Sergio, who had been educated in French schools his whole life, was admitted, while da Silveira was not and went instead to the University of Paris at Nanterre. It was at the Sorbonne, studying under the legendary moral philosopher Vladimir Jankélévitch, that Sergio received an in-depth introduction to Marx and Hegel and proclaimed himself a student revolutionary.

In May 1968 he was one of some 20,000 students who took to the streets against the de Gaulle government, demanding greater say in the national university system and calling for the abolition of the “capitalist establishment.” In the worst fighting Paris had seen since 1945, riot police stormed student barricades with tear gas, water cannons, and truncheons, arresting Vieira de Mello and nearly six hundred other student protesters. The gash he received above his right eye was so severe that he would require corrective surgery thirty-five years later. Arnaldo drove in an official car from the Brazilian consulate in Stuttgart to Paris to see his son. When Sergio learned that his father had parked in the Latin Quarter, he exclaimed, “Run back there and move the car! The students are burning all the cars there today!” The standoff would become so violent that the rector of the Sorbonne would close the university for the first time in its seven-hundred-year history.

After a few weeks the French public began to turn against the protests, and workers who had joined the students in striking returned to work out of fear they would lose their jobs. After the student revolt had fizzled, Sergio penned a lengthy letter to the editor of the French leftist daily newspaper

Combat complaining that the mainstream press was delighting in denigrating the student revolt. In his first published writing, he commended the violence as “salutary,” noting that if the students had staged only peaceful rallies on the university campus, the French public would have looked the other way. Street fighting had been necessary in order to get the attention of an indifferent public.“One can awaken the masses from their lethargy only with the sound of animal struggle,” he wrote.

9

But unless the struggle became “global, irreversible, and permanent” and brought about the “demise of fossilized thought,” he argued, the students would go down in the French annals as “the organizers of a huge and laughable folkloric bazaar.” He closed his letter with a raging salvo against the “old scum.”“Let them cry over their repugnant past, let them worship their lost pettiness, let them fatten themselves at will,” he wrote.“One thing is now certain: their tranquillity has disintegrated. We may be walking toward our most resounding failure, but their victory will also be their hell.”

10

Sergio was so proud of his irate debut that he passed around copies of the article to friends. Although he could not have imagined it then, May 1968 would prove the apex of his antiestablishment activism.

Word of his contribution to Combat quickly reached his family in Brazil. His sister, Sonia, spotted a news item in one of the Rio newspapers describing a Brazilian student involved in the Paris clashes who had returned home and been abducted and murdered, presumably by the military regime. She panicked and passed the article along to a friend who was traveling to Europe. When Arnaldo saw it, he told his son that he should not risk returning to Brazil anytime soon. The French government had granted amnesty to foreign students arrested in the riots, but it required them to check in with the authorities at the police station on a weekly basis. This seemed a small price to pay for continuing his education at the Sorbonne, and Sergio went back to class in the fall of 1968 in the hopes of combining his credits from Rio, Fribourg, and Paris to graduate in 1969.

Although he relished the educational rigors of the Sorbonne, he was lonely in Paris and nostalgic for Rio. “People don’t exist here,” he wrote to a girlfriend in Geneva in March 1969. “I spend my time with books.”

11

His letters grew increasingly mournful as he noted that “for two years nothing has changed except myself. Complaining of the crowds, cars, noise, and “an uninformed mass that I’m tired of, ” he wrote that he missed “the days where I could walk alone with my sea birds.”

12

But back in Brazil the military dictatorship was growing more repressive. Paramilitary forces roamed the country arresting and often torturing those suspected of subversive activity. Well-known Brazilian diplomats such as Vinicius de Moraes, who in his spare time had helped launch the bossa nova genre by writing the lyrics for such songs as “The Girl from Ipanema,” were dismissed from the foreign diplomatic corps. In the spring of 1969, five years after the initial coup, Arnaldo Vieira de Mello, who was neither well known nor openly critical of the military regime, was sitting at the breakfast table of his residence in Stuttgart, sipping his morning coffee, reading the morning papers, and flipping through Brazil’s diplomatic digest. As he scanned the list of civil servants whom the military regime had forced into retirement, his eyes fixed suddenly upon a name he had not expected to find: his own. He had been sacked by a government he had served for twenty-eight years.

Sergio was in Paris when he learned the news. He raged at the Brazilian government for hurting his family and complained that his father had been fired for his political views. But Arnaldo’s colleagues and relatives speculated that his worsening drinking habit may also have been a factor. The military regime offered no explanation.

As Arnaldo packed up his life in Europe, he told his son that he would not be able to pay for his graduate studies at the Sorbonne. In May, just two months before graduation, Sergio wrote again to the young woman he had dated when he was in Geneva. Sounding depressed and confused about his future, he informed her that his father had been fired. “The dictatorship is a reality,” he wrote.“I will be obliged to earn my bread starting in August.” He would try to find work but had “no idea” where. “My future is more than up in the air.”

13

In June he wrote to her that he expected to receive high marks in his philosophy exams. (He would in fact dazzle the Sorbonne faculty, finishing first out of 198 candidates in metaphysics.) “But for what?” he wrote sarcastically. If he had studied economics or marketing instead, “some American company would have assured me a ‘happy’ future strewn with dollars.” He would never sell out, he told her, and “just short of dying of hunger,” he would “never abandon philosophy.” The philosopher, he wrote, could become either “the most just man” or “the most radical bandit.” Either way, he insisted, “to do philosophy is to have it in your blood and to do what very few will do—to both be a man and to think everywhere and always.”

14

After trying briefly to find a philosophy teaching job, Sergio made his way to Geneva, where the da Silveira home had become his European base. He decided to try to find work with one of the many international organizations there. Knowing Sergio’s gift with languages (he already spoke flawless Portuguese, Spanish, Italian, and French), an acquaintance of his father’s put him in touch with Jean Halpérin, the forty-eight-year-old Swiss director of the language division at the United Nations. Halpérin had hesitated to take the meeting because he knew of no available jobs, but when they met, he was immediately taken in by the young man’s passion for philosophy. Halpérin offered to call the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), which often needed ushers for large conferences on the preservation of cultural monuments. “Thank you very much,” Sergio said, smiling politely. “I know UNESCO, and it is not my cup of tea. My sense is that it is a lot of ‘blah, blah, blah.’” Surprised that someone unemployed would be so picky, Halpérin explained that his academic background would not leave him many options within the United Nations. “I’m very sorry, Sergio,” he said, “but the UN deals with everything under the sun except philosophy.”

A few days later Halpérin received a call from a colleague at the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), which was looking for a French editor. UNHCR performed two main tasks—it gave people fleeing political persecution the material assistance they needed to survive in exile, and it tried to ensure that the displaced were not forced back to the countries that had driven them out. The United Nations required fluent English and two years of professional experience. Sergio spoke little English and had never held a full-time job, but he interviewed better than any of his fellow applicants and was given a temporary contract. He started his career at UNHCR in November 1969 and would spend the next thirty-four years working under the UN flag.

“WHAT WOULD JAMIE DO?”

Almost as soon as he took up his post at UNHCR, he began hearing tales of a man who was every bit his opposite. Vieira de Mello was a twenty-one-year-old Sorbonne-educated, multilingual Brazilian with a lean physique and a movie-star smile. Thomas Jamieson, UNHCR’s director of field operations, was a fifty-eight-year-old pale, balding, rotund, bespectacled Scotsman who had never graduated from secondary school. And although Jamieson had lived in and out of French-speaking countries since the Second World War, he prided himself on having never bothered to master French. Despite these cosmetic differences, Vieira de Mello quickly found a mentor in the man known as “Jamie.”

Jamieson had joined UNHCR in 1959 after working with UN and nongovernmental groups to resettle German, Korean, and Palestinian war refugees. Vieira de Mello actively sought him out, peppering him with questions about his experiences. Warm and instantly accessible to those he liked, Jamieson was not an intellectual like Vieira de Mello’s father, but he placed a similar emphasis on audacity, and he shared Arnaldo’s taste for scotch. First-time visitors to Jamieson’s home near Geneva knew they had reached their destination when they saw the trash cans outside overflowing with empty whiskey bottles. Whether he was in his office at UNHCR or roaming around some dusty outpost in Nigeria, Jamieson always invited colleagues to join him for his close-of-business drink of Johnnie Walker Red Label. More than five thousand miles from his family and discouraged from returning to Brazil, Vieira de Mello seemed to prize the new bond.

Jamieson explained that his overarching aim—and that of the UN—was simple: “Children should have a better and happier life than their parents.” He decried the refugee camps that had clogged the European continent after World War II.“If there is a way to avoid setting up a camp, find it,” he would say. “If there is a way to close a camp, take it.” His central message, conveyed to all who encountered him, was that “UNHCR ought to endeavor to eliminate itself.”

15

Over long lunches in Geneva he warned Vieira de Mello that charitable enterprises could quickly grow more concerned with their own self-perpetuation than with helping the needy. Jamieson urged him to be sure to distinguish the interests of the UN, his place of employment, from the interests of refugees, his reason for working.

Jamieson generally managed field operations from afar, spending most of his time at UNHCR headquarters in Geneva. But when he ventured overseas, he made the most of it, ostentatiously arriving back, in the words of one colleague, “with the red dust of the Sahara still on his safari suit.” He used slide shows and stirring oral accounts of the suffering of refugees to spice up the sterile and impersonal chambers of the Palais des Nations, where UN staff and ambassadors from donor countries gathered. Jamieson often sounded contemptuous of diplomats. “You’re all sitting here in comfort,” he would say after a trip.“I’ve come from the real world where the action is and where the answers are.” He was never shy about voicing his impatience with legal hair-splitting, UN red tape, or diplomatic pomposity, and he despised the incessant and interminable array of meetings his job required. It was not uncommon for him to stroll fifteen minutes late into a coordination session that he was supposed to chair. “Ohhhh so I see we are having a meeting. How charming,” he would say.“If there’s one thing in the world I like, it is meetings. Tell you what we are going to do: I’ll tell you what I have decided, then we can meet for as long as you wish!” Undemocratic in his approach, Jamieson got his way by relying upon his personal relationship with Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan, the powerful and visionary high commissioner who ran UNHCR.

2

Although Sadruddin could find Jamieson taxing, he valued his ability, in the words of a colleague, to “kick bean-counters with such finesse.”While Vieira de Mello had none of Jamieson’s willingness to make enemies, he shared his mentor’s distaste for bureaucracy.

Vieira de Mello had joined UNHCR at an electrifying time. Under the leadership of Sadruddin, UNHCR shifted its emphasis from Europe, where refugees from World War II and the Soviet Union had commanded attention in the 1940s and 1950s, to Africa and Asia, where decolonization wars had created new refugee flows in the 1960s and 1970s. Of all the UN agencies, UNHCR had the best reputation among aid workers and donor governments. The U.S.-Soviet rivalry had neutered the Security Council, but UNHCR, which had its own governing board, or executive committee, had managed to thrive. It had already won one Nobel Prize—in 1954, for resettling European refugees after the Second World War—and was on its way to another in 1981, for managing the flight of refugees from Southeast Asia. As UNHCR expanded its work from Europe to Latin America, Africa, and Asia, staff members who spoke multiple languages or hailed from the developing world were put to use. Vieira de Mello, who had been UNHCR’s youngest professional staff member when he joined at twenty-one, rose more quickly than most of his peers.

His leftist ideals still brewed close to the surface. Although he did not romanticize Communism as it was being practiced in the Soviet Union, China, or Cuba, he slammed the United States for its war in Vietnam and its support for repressive right-wing regimes like Brazil’s. When he spotted an American-made car while walking down the streets of Geneva with friends, he would bend down as if picking up a stone and make the motion of hurling it at the passing vehicle. “Imperialists!” he would exclaim. In restaurants too when he heard an American accent, he occasionally made a show of getting up and moving out of earshot. “You can just hear the capitalism in their voices,” he would say with disdain.

Although he had stopped attending classes at the Sorbonne after receiving his basic degree in philosophy in 1969, he had continued to work toward his master’s from afar, reading and writing mainly at night and on the weekends. In 1970 he used up his UN vacation days studying for his oral exams and earned a master’s from the Sorbonne in moral philosophy. He still viewed the UN as a place of temporary employment. Although Jamieson had captured his imagination, the UN’s byzantine procedural requirements had not. He wrote to his former girlfriend in July 1970 that the UN had not changed: “From the sludge, I have only been able to learn one thing: the inanity of a life filled with forms of imaginary content.”

16

Jamieson never asked about his protégé’s philosophical pursuits, which he found excessively abstract, but Vieira de Mello did not mind. He laughed whenever Jamieson contrasted his own self-made path with that of his overcredentialed, privileged colleagues. “If I had a formal education,” Jamieson liked to say impishly, “I wouldn’t be working in this office. I’d be prime minister of England!”

A few of Vieira de Mello’s colleagues felt that he was too forgiving of Jamieson’s condescension.“Jamie was friendly,” recalls one, “but his friendliness was like that of a colonial sahib who treated his Indian valet nicely.” Jamieson sounded like many Western visitors to Africa when he spoke admiringly of its people, telling a UNHCR newsletter of “their great sense of humour; their happy spirit even in great difficulties.”

17

Vieira de Mello saw those colonial tendencies as forgivable by-products of Jamieson’s age and upbringing.

In 1971, two years into his time at UNHCR, Vieira de Mello was transformed by his first-ever field mission. The agency had taken on its largest challenge to date, managing the entire UN emergency response to the staggering influx into India of some ten million Bengalis. Pakistan had forced them out of their homes in the eastern part of the country, which would soon become Bangladesh. UNHCR’s global budget was then only $7 million, but High Commissioner Sadruddin raised nearly $200 million to contribute to an operation that would cost more than $430 million.

18

Operating under fierce pressure, Jamieson brought his favorite staff to the region—first to India to manage the refugee arrivals, and then to newly independent Bangladesh to help lay the ground for the massive return. He shuttled around as if he owned the region, even calling Indian prime minister Indira Gandhi “my dear girl.” Vieira de Mello, who was only twenty-three, was based in Dhaka, Bangladesh, where he helped organize the distribution of food aid and shelter to Bengalis as they returned home. When he disagreed with his boss, Jamieson would tell him, “My dear boy, you are completely and utterly wrong.”

For the first time in his life, Vieira de Mello felt he was doing something practical to operationalize his philosophical commitment to elevating individual and collective self-esteem. Human suffering—starvation, disease, displacement—would never be abstractions for him again. “Bangladesh was a revelation for Sergio,” recalls his Brazilian friend da Silveira.“By being in the field, he recognized a part of himself he had never seen before. He understood he was a man of action. He was made for it.”

Around the same time that Vieira de Mello had fallen under Jamieson’s spell, he met Annie Personnaz, a French secretary at UNHCR. The two began dating, and just as Arnaldo had done with Gilda’s family, Vieira de Mello grew close to Annie’s parents, who owned a family hotel and spa in Thonon, France.

In May 1972 Jamieson, who was sixty, retired in accordance with UN rules. He was miserable and kept his eyes glued to the newspapers for a chance to return to duty. When the government of Sudan signed a peace agreement with southern rebels, seemingly ending a seventeen-year civil war and paving the way for the return of some 650,000 Sudanese refugees and displaced persons, Jamieson saw his opportunity and persuaded the high commissioner to ask him to come out of retirement to lead the effort. Just as Vieira de Mello’s courtship with Annie was intensifying, Jamieson asked him to join a small team helping organize the return of the Sudanese refugees. Vieira de Mello wrote Annie letters while he was in southern Sudan, and she even visited him in the capital, Juba. He soon pro-posed,

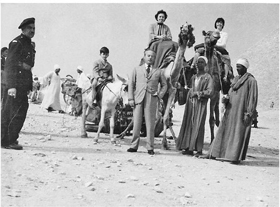

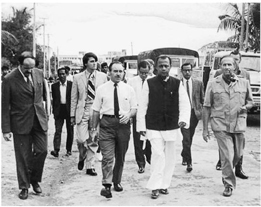

Vieira de Mello (in a light-colored suit, third from left) walking in Dhaka, Bangladesh, with a delegation that included UNHCR’s high commissioner Sadruddin Aga Khan (far right), November 1972.

and they scheduled their wedding for June 2, 1973. Flavio da Silveira would be his best man.

The Sudan mission afforded Vieira de Mello the chance to work more closely with Jamieson than he ever had before. Rotating between Geneva, Khartoum, and Juba, he helped his mentor establish an airlift that transported food, medicine, farming tools, and the returning refugees themselves. Jamieson could be an ingenious problem-solver. When he saw that an antiquated barge was the only means of carrying commercial traffic across the Nile River, he declared, “If we’re going to bring these people home, we need a bridge.” But UNHCR passed out food; it didn’t build bridges. So Jamieson began appealing to Western governments. When he made the case on charity grounds alone, he got nowhere. But in discussions with the Dutch government, he found an argument that worked. “This will be a training exercise,” Jamieson said. “The Dutch military engineers can use this as a drill to see how quickly they can build a bridge in difficult circumstances.” Initially Jamieson’s scheme looked doomed because the Sudanese rejected the presence of Western soldiers on their soil, and the Dutch military refused to perform the task out of uniform. But Jamieson quickly devised a compromise formula by which the Dutch would wear their uniforms without Dutch insignia. The all-steel Bailey bridge, which was completed in the spring of 1974, opened up southern Sudan to Kenya and Uganda, vastly increasing the flow of people and goods into the area.

Vieira de Mello watched Jamieson take what he had seen in the field and turn it into a fund-raising pitch at headquarters. At a press conference in Geneva in July 1972, decked out in a suit and tie, with a matching handkerchief and prominent cuff links, Jamieson argued that what the Sudanese wanted was not emergency relief but development assistance.“I found they are more interested in seeing something long-range done for their children, than in food,” he said. “Strange. I’d like to see

us in similar circumstances. I’d ask for fish-and-chips first and then talk about education second.”

19

Vieira de Mello saw that while UNHCR had become skilled at feeding people in flight, governments were far less adept at preventing crises in the first place, or at rebuilding societies after emergencies so they could become self-sufficient.

Jamieson carried his taste for scotch with him on the road, and Vieira de

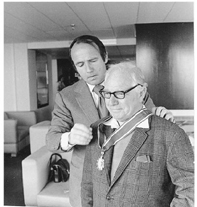

High Commissioner Sadruddin presenting Thomas Jamieson with the Sudanese Order of the Two Niles on behalf of Sudanese president Jaafar Nimeiri, 1973.

Mello eagerly joined in. “Don’t bother with antimalaria pills,” Jamieson told a young Iranian colleague Jamshid Anvar. “Whiskey is the best vaccine for everything.” But the drinking took its toll. Jamieson’s complexion grew ruddier, and in May 1973 he suffered a mild heart attack. The doctor told him to ease his workload.

Vieira de Mello juggled his own duties in Sudan with the planning of his wedding in the French countryside. He had invited both of his parents to attend the ceremony, but Arnaldo declined. Back in Brazil, without work, he had retreated further into himself. His drinking picked up, and his health grew worse. His depression had deepened in 1970 when his youngest brother, Tarcilo, was killed by a passing car as he exited a taxi in Rio. Gilda urged her husband to reconsider their son’s wedding invitation, but Arnaldo said that he was only halfway through his second book and needed to finish. Gilda was upset. “How am I going to attend my son’s wedding ceremony by myself?” she asked. “I want to go with my husband. I am not a widow.” But Arnaldo insisted that on his small pension he could not afford to buy new suits for both the religious and the civil ceremonies, and he would not appear in the same suit at the two events. In all likelihood he was not feeling well enough to travel.

Gilda, Sonia, and André, Sonia’s six-year-old son and Vieira de Mello’s godson, flew to France for the wedding. On June 12,1973, ten days after the couple had wed, Sonia, who had traveled on to Rome, received a telephone call from a friend in Rio: Arnaldo, fifty-nine, had suffered a stroke and pulmonary edema and died. Gilda, who was reached in London, was devastated. Vieira de Mello had driven with Annie across Europe to Greece. The couple had just arrived at the hotel to start their honeymoon when he got the news. Vieira de Mello had worried about his father’s health for years and was not surprised, but he was deeply saddened. He put the couple’s luggage back into the car, drove back to France, and flew alone to Brazil, where he arrived in time for the memorial service. In 1992, after years of trying to find a publisher for his father’s incomplete manuscript, Sergio would himself pay to have it published in Brazil.

20

With the sudden death of his father, Vieira de Mello grew even closer to his mother. For the rest of his life, no matter where he went in the world, he made a point of speaking to her at least once—but usually several times—each week. She also became a one-woman clipping service, tearing out articles from the Brazilian press that pertained to the places her son had worked. Vieira de Mello’s ties to Jamieson also grew more intense. Jamieson had taken one lesson from his heart attack: Work was a “blessing,” and he needed to get back to it. He had always been dismissive of physical hazards of any kind. When two of his colleagues were badly injured in an attack in Ethiopia, High Commissioner Sadruddin had considered withdrawing UN staff, but Jamieson had ridiculed the idea. “Prince, look,” he had said, “if you don’t want to take any risks, you might as well go out and sell ice cream.”

Jamieson maintained an indefatigable pace, ignoring his doctor’s orders to avoid the scorching equatorial sun. Often with Vieira de Mello by his side, he crisscrossed the vast Sudan, personally visiting camps and villages to ascertain whether returning refugees would have the water and fertile soil they needed in order to survive. In late 1973, while Jamieson was visiting refugee camps in the eastern part of the country, he collapsed and was rushed by plane back to Khartoum. The doctors told him his heart condition was severe but released him so that he could spend the night back in his room at the Hilton Hotel. A panicked Vieira de Mello helped to arrange the medical evacuation to Geneva and volunteered to remain by Jamieson’s bedside throughout the night.

Anvar, the Iranian UNHCR official, had been with Jamieson when he collapsed. When he spotted Vieira de Mello at the hotel, he said,“Sergio, you must be crazy to want to stay up all night with him.”

“He might need help,” Vieira de Mello said.

“He is in absolutely no danger,”Anvar said. “The hospital would not have released him if there was a risk.”

“I will not be able to sleep,” Vieira de Mello said. “And I don’t trust doctors anyway.”

“I don’t understand you,” Anvar countered. “Jamie is condescending and patronizing toward anybody who isn’t British. He is everything that you are not and you are everything that he isn’t. What do you see in him that I can’t see?”

“He’s like a father to me,” Vieira de Mello said simply. "I love the man.”

The following day Vieira de Mello flew with Jamieson back to Geneva. Jamieson survived the incident but never returned to the field or recovered his health. He died in December 1974 at the age of sixty-three.

Vieira de Mello turned back to developing his philosophical theories, which had taken a practical turn. On returning to Geneva from Bangladesh, he had reached out to Robert Misrahi, a philosophy professor who specialized in Spinoza at the Sorbonne and whom he had studied with in the past. “He was a young student settling down intellectually,” Misrahi remembers. “He was extremely intelligent and dynamic, but he was without a doctrine. Fueled by painful personal experiences—his father’s firing, his own exile, and what he had witnessed in Bangladesh—he wanted to be a man of generous action or a man of active generosity.”

21

Under Misrahi’s supervision, Vieira de Mello completed a 250-page doctoral thesis in 1974, entitled “The Role of Philosophy in Contemporary Society.” He took several months of special leave without pay to finish up, relying upon Annie’s UNHCR salary. Forgiving of her new husband’s relentless work habits, she threw herself into the process, typing up his manuscript for submission.

The thesis took aim at philosophy itself, which he deemed too apolitical and abstract to shape human affairs. “Not only has history ceased to feed philosophy,” he wrote, “but philosophy no longer feeds history.” He credited Marxism with being the rare theory that attempted to play a role in real-life human betterment. By defining the contours of a social utopia, Vieira de Mello argued, Marxism at least laid out benchmarks that could inspire political action. Although he was pleading for a more relevant and political philosophy, Vieira de Mello wrote in the dense, jargon-filled style of Paris in the 1970s. He argued that the core philosophical principle that should drive human and interstate relations was “intersubjectivity,” or an ability to step into the shoes of others—even into the shoes of wrongdoers. If philosophers could help broaden each individual’s ability to adopt another’s perspective, he argued, they could help usher in what Misrahi called a “conversion.”

22

UNHCR continued to offer assignments that kept pace with his growing appetite for adventure and learning. In 1974, still just twenty-six, he helped manage the mechanics of aid deliveries to Cypriots displaced in the Greek-Turkish war. “Leave all the logistics to me,” the young man told Ghassan Arnaout, his Syrian supervisor in Geneva. “You keep your mind on the political and the strategic picture, and I’ll handle the groceries.” Vieira de Mello already seemed to view the assistance that UNHCR gave refugees— or “grocery delivery”—as a routine household chore. He had a lot to learn about protecting and feeding refugees, but if he remained within the UN system, he told Arnaout, he hoped to eventually involve himself in high-stakes political negotiations.

He and Annie lived in an apartment near her parents’ home in the French town of Thonon. After a few years they built a permanent home for themselves in the French village of Massongy, a twenty-minute drive from Thonon and a half hour from his workplace in Geneva. In 1975 the couple moved to Mozambique, where he joined a UNHCR staff that was caring for the 26,000 refugees who had fled white supremacist rule and civil war in neighboring Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). He had been named the deputy head of the office, but owing to an absent boss he ended up effectively running the mission, an enormous responsibility for one just twenty-eight years old. Initially the novelty of new tasks and a new region sustained him. He particularly enjoyed getting to know independence fighters and leaders from Rhodesia, South Africa, and East Timor, the tiny former Portuguese colony that had just been brutally annexed by Indonesia. Yet after a year in the job he began mailing long, restless letters to his senior UN colleagues in Geneva, inquiring about other job postings. It was as if, as soon as he settled into a routine by helping develop systems to house and feed the refugees, he was eager to move on. When word of these ambitions began circulating around UNHCR headquarters, Franz-Josef Homann-Herimberg, an Austrian UN official whom Vieira de Mello had often approached for career advice, warned him, “Sergio, you’ve got to cool it. It is natural that you don’t want to wait until jobs are offered to you, but you are starting to get a reputation for being one who spends his time plotting his next move.”

In 1978 Vieira de Mello and Annie returned to France, where she gave birth to a son, Laurent. Then they moved to Peru, where Vieira de Mello became UNHCR’s regional representative for northern South America and attempted to help asylum-seekers who were fleeing the Latin American military dictatorships. This assignment moved him closer to home, allowing him to spend more time in Brazil than he had in the previous decade. In 1980 he and Annie had a second son, Adrien.

Vieira de Mello kept a permanent stash of Johnnie Walker Black Label— an upgrade from Jamieson’s Red Label—in his desk drawer at his UNHCR office or in his suitcase while on the road. He also kept a framed photograph of his mentor on his desk at UNHCR. He took it with him on most field assignments and sometimes placed it on hotel nightstands during short overseas trips. A decade or so after Jamieson’s death, Vieira de Mello called Maria Therese Emery, Jamieson’s longtime secretary, and apologetically asked if she might be able to give him another photograph of Jamieson. “I’ve been in too many hot places,” he said. “The photo I have has faded in the sun.”