Twelve

INDEPENDENCE IN ACTION

Vieira de Mello believed that the potential political and humanitarian benefits of inserting himself and his hastily assembled UN team into a live war zone vastly outweighed the physical risks. But even as he made his way to the region, the Clinton administration stepped up its criticism of his trip. On May 16, 1999, Secretary-General Annan, who was staying at the home of Queen Beatrix in the Netherlands, received a furious phone call from Thomas Pickering, the under secretary of state for political affairs, who was calling from the United States, where it was 4 a.m. Pickering told Annan that he had just seen Vieira de Mello’s itinerary and it was unacceptable. The UN delegation would be in the region for eleven days, but in Kosovo for less than three of those, from Thursday afternoon until Saturday morning. Washington officials remained concerned that the UN team would see the power plants and bridges NATO had hit in Serbia, but that they would not get an accurate picture of the destruction and bloodshed the Serbs had caused in Kosovo. “Milošević is going to get huge propaganda mileage out of this,” Pickering said. He advised Annan to cancel the mission unless the Serbs allowed at least three-quarters of it to be spent in Kosovo. Annan refused.

When Annan’s special assistant Nader Mousavizadeh tracked down the UN envoy in the lobby of the Sheraton Hotel in Zagreb, Vieira de Mello said he was fed up with American bullying. He had already heard twice from the U.S. mission in New York, once from the U.S. representative in Geneva, and the night before from Pickering himself. He was aware of the danger that, on such a short, restricted trip, he would hand the Serbs a public relations victory, but he expected to bring back useful information. “Enough is enough,” he told Mousavizadeh. “I am on a needs-assessment mission. I will do what I have to do to assess needs!”

When he rejoined his assembled team in the hotel lobby, he said, “The Americans are livid. They are refusing to offer us security assurances. Each of you should decide for yourself whether you still want to be a part of this mission. I am going to go ahead, but that should not influence your decision.” The very fact that Washington was so hostile to the trip only strengthened the team’s sense that they were right to attempt to conduct an independent investigation. Almost all of those gathered had experienced war before, and many thought the risk of being struck by one of NATO’s precision-guided munitions was low in comparison to the dangers they had faced in other war zones. None of the team members dropped out.

While Western officials had reasons to be anxious, the Serb authorities should have been concerned as well. Milošević was trying to pretend as though Kosovar Albanians were leaving voluntarily or fleeing NATO air strikes. “Everyone runs away because of the bombing,” Milošević told CBS News. “Birds run away, wild animals run away.”

1

He urged the public not to believe the deceitful Western media. “I personally saw on CNN at the beginning of this war poor Albanian refugees walking through snow and suffering a lot. You know, it was springtime at the time in Kosovo,” he said.“There was no snow. . . . They are paid to lie.”

2

He noted that while the Serbs may have occasionally burned “individual houses,” their misdeeds did not compare to Vietnam, where “American forces torched villages suspected of hiding Viet Cong.”

3

The reports of the number of Kosovar Albanian men who had gone missing ranged from 10,000 to 100,000.

4

Vieira de Mello believed his team could improve the clarity of the picture. “It’s the first time we are able to embark in this kind of way and right in the middle of a war,” he told journalists after driving from Zagreb to Belgrade.

5

He said that he hoped to talk to those Kosovar Albanians in hiding who had been unable to escape to a neighboring country. “Many say this mission is madness,” he said, but only officials with the UN could reach “those who are in desperate need inside Kosovo.”

6

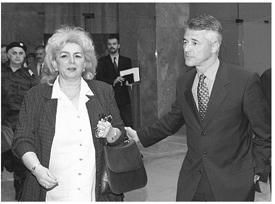

After driving from Croatia to Serbia, he held meetings with Serb officialdom that were tense and interminable. The Serbs directed their rants against NATO at him personally. “I don’t know how he put up with all he heard,” says Sarah Uppard, then a forty-three-year-old aid worker with Save the Children. “I would have lost it several dozen times over. But he managed to be firm, patient, and charming at once. He made everybody feel listened to without making even the slightest concession. Even the most aggressive officials found themselves taken in by him.” The minister of refugees, Bratislava Morina, was a close friend of Mira Marković, Milošević’s wife, and was used to getting her way. She denounced NATO for its “genocide” against Serbs and slammed the UN for failing to prevent the war. Yet by the end of the meeting, she was a different woman.“Sergio had her eating out of his palm,” recalls Kirsten Young of UNHCR.

On May 18 his UN team left Belgrade and embarked upon an investigation that would take them almost nineteen hundred miles in eleven days. They traveled in a fleet of ten white Toyota 4Runners, each marked with a large black “UN” logo. Terry Burke, the UN head of security for the mission, brought a separate stack of large black UN decals and plastered one to the roof of each of the cars. “I don’t want to get blasted for an error,” Burke

Vieira de Mello and Yugoslav minister of refugees Bratislava Morina, May 1999.

told Vieira de Mello. “If we get hit, I want everyone to know that whoever hit us did so

because we are the UN.” The UN convoy was led and trailed by a Serbian police car. Burke had attempted to draft a getaway contingency plan, but he had just ended up with question marks. “Getaway where? With what?” he had asked himself. “If you run away from the Serb paramilitaries on the main roads, then you end up on the side roads vulnerable to NATO bombers.”

The first stop on the UN tour was the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, which had been struck eleven days before. When the UN team reached the ruins of the building, Vieira de Mello shook his head in disbelief at the sight before him: The attack had blown a six-foot-deep crater out of one side of the building and a pair of gaping holes out of the other side. One of the walls seemed to have been peeled off, revealing, like the exposed interior of a dollhouse, the desks, bookshelves, couches, and artwork of the embassy, which, though covered in a thin layer of dust, remained intact. “NATO is precise all right,” Vieira de Mello muttered to a colleague. “They just hit precisely the wrong target.”

It had not been easy to find drivers willing to transport a UN delegation into a three-way battlefield. UN policemen who worked in neighboring Bosnia had lent themselves to the mission, but this meant that the drivers of the vehicles were not professional drivers and were not from the region. (The full-time drivers in Bosnia were natives of the area and thus could have become targets.) Already two of the UN cars in what had originally been a twelve-vehicle fleet had failed to show after getting lost on the drive up from Sarajevo.

After leaving the Chinese embassy, the driver of Vieira de Mello’s lead vehicle suddenly noticed that the rest of the convoy was no longer visible in the rearview mirror. Once their car turned around and drove a mile back up the road, Vieira de Mello saw an overturned UN 4Runner on the horizon. Horrified, he pieced together what had occurred. The route was heavily trafficked because NATO had bombed several of the major roads. A Serb driver had become so transfixed by the sight of ten white UN vehicles speeding toward him on the other side of the road that he did not notice until the last minute that the traffic in front of him had stopped. Instead of ramming the car in front of him, he had swerved into the oncoming traffic, where a Ghanaian UN policeman was zooming toward him recklessly at close to eighty miles per hour. In order to avoid a head-on collision, the Ghanaian had jerked his car toward the side of the road. As he did, he lost control of the vehicle, which flipped in the air, hit a tree, and landed upside down in a ditch.

Bakhet, who was traveling in the car directly behind the vehicle that crashed, had only looked up in time to see a large white vehicle flying through the air, for seemingly no good reason. Although he had given up smoking, he was so shaken that he asked for a cigarette, then nervously joined in the team’s effort to remove the injured UN officials from the wreckage. His cigarette hung precariously out of his mouth as diesel trickled slowly out of the car’s tank and out of jerry cans in the trunk.

The men pulled out of the vehicle were Nils Kastberg and Rashid Khalikov, who had led the advance mission to Belgrade the week before. Trembling and pale on the side of the road, Khalikov had multiple fractures in his upper left arm and lower back. He shouted, “My mobile, give me my mobile.” He wanted to call his wife. Kastberg was also disabled with multiple fractures to his right foot.

Vieira de Mello rushed between Kastberg and Khalikov. He instructed the Yugoslav security services to call an ambulance and turned to David Chikvaidze, an aide whose job it was to maintain contact with NATO headquarters. “Tell them that we have two men down,” he said, “and to go easy on the bombing around Belgrade hospitals.”

Nothing seemed to be going according to plan. NATO had refused to guarantee the security of the mission. The Serbs had routed the delegation away from the terra incognita of Kosovo to towns in Serbia proper, where Western journalists were already present in droves. And finally, no sooner had the UN convoy left Belgrade and begun the journey into the countryside than it had been felled by a serious road accident. “I can see the Serbian papers tomorrow,” Vieira de Mello quipped. “A photo of one of our cars in the

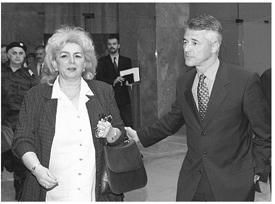

Vieira de Mello comforts an injured Nils Kastberg of UNICEF.

ditch, and the caption, ‘Beware, the UN has arrived!’ ” Most team members had the same reaction as they took in the scene, saying to themselves, out loud or in their heads, “Classic UN!”

Once Kastberg and Khalikov had been bundled off to the hospital, Vieira de Mello set about comforting the other team members. Kirsten Young, who had been ambivalent about joining the UN team to begin with, was asking herself, “What the hell am I doing here? We have no idea what we’re doing!” As Young remembers, “You fear you are going to get bombed, but instead of getting bombed, you have a car crash completely of your own making.” Dr. Stéphane Vandam, the WHO representative on the team, had helped organize the medical evacuation. He too began to wonder whether they were in over their heads. “We were standing up for humanitarian values, putting them back in the hands of Kofi Annan, and taking them away from the politicians,” he remembers. “It was a brave mission, but it began then to feel like a very stupid mission.” After the accident Vieira de Mello went out of his way to give off an almost exaggerated air of confidence. Young recalls,“I was terribly frightened. I didn’t trust our drivers, I didn’t trust our security guys, and I didn’t trust the Serbs or NATO. Yet every time I looked up and saw Sergio smiling, I thought to myself, ‘If Sergio is here, it’ll be okay.’ He was a Teflon guy in the sense that nothing bad seemed to touch him.”

The delegation continued onward to the town of Novi Sad, in the Serbian province of Vojvodina. There they saw the Sloboda (Freedom) bridge collapsed in the Danube River. It was the second of Novi Sad’s three bridges hit in the early days of the NATO air campaign. Confronted with the hysteria and rage of Yugoslav authorities and Serb civilians, Vieira de Mello tried to argue that the UN had not authorized the war and that it and NATO were distinct entities. His hosts were unpersuaded. After the UN delegation had concluded a meeting with one Serbian town mayor, Chikvaidze spotted a poster on the door to the city hall with an image of a skull capped by a UN helmet, and he asked a burly Serb guard in the lobby of the building whether he could take the poster with him. The guard shrugged a grudging acceptance, as if to say, “Everything is now possible in my country.” Vieira de Mello shook his head when he saw the poster. “That is the predicament the UN is in,” he said.“What the Serbs are saying with that poster is, ‘The UN is no better than NATO. Because you didn’t stop NATO from doing this, you are all the same.’ ” When Vieira de Mello would go to Iraq in 2003, many would similarly blame the UN for failing to stop the U.S.-led invasion.

Vieira de Mello was alternately impressed and horrified by NATO’s aim. While he talked to villagers in one southern Serbian city, he heard a whistling sound and looked up to see a cruise missile flying through the sky. “Wow,” he exclaimed with boyish wonderment as the missile crashed in the distance. “Thank you, General Electric, for not screwing that one up.” Ten miles down the road, the mission encountered the burning ruins of a Serb police station that the missile had struck.

Just before the UN team sat down to a dinner hosted by officials in Niš, Yugoslavia’s third-largest city, the Serbian government host presented Vieira de Mello with photographs of the cadaver of a pregnant woman who he claimed had been killed by a NATO strike. The Serb official ended his presentation by circulating pictures of a destroyed fetus. Vieira de Mello was disgusted by the images, but he was just as outraged by the Serbs’ willful exploitation of the carnage. A Serbian reporter asked him about the photographs he had seen. “They’re deplorable,” he said sternly. But he added, “I’ve told you what I think you need to do to stop that.”

7

He knew that once he reached Kosovo, he was likely to find many such gruesome scenes—the victims of Serbian ethnic cleansing.

Throughout the trip he remained concerned about the fates of Kastberg and Khalikov, who were sharing a room in the intensive care unit of Belgrade Central Hospital. In solidarity with the mission, the men had refused to be evacuated back to Geneva and had undergone surgery in Belgrade. Vieira de Mello thus had to worry not only about the safety of the personnel in his convoy but also about them. Nonetheless, he was personally moved by their courage and loyalty, and knowing that they were crestfallen to have been sidelined after planning the trip, he telephoned them nightly in order to keep them in the loop. “He would tell us exactly what the mission had done that day,” Khalikov remembers. “He wanted to show us we were still part of the team.” Each night when Vieira de Mello checked in with the men, he could hear the crash and thud of bombs landing nearby. “We both knew that if something went wrong, we wouldn’t be able to run,” recalls Khalikov. “I was lying flat. I couldn’t get up. Nils couldn’t walk.” The men had also been warned upon arrival that a likely NATO target, the ministry of the interior, was located nearby. Although NATO had been given the coordinates of the hospital, the men had seen the wreckage of the Chinese embassy and knew that deadly mistakes were possible. Kastberg assured Vieira de Mello that the morale of the two patients was high. “Between us, we have three legs and three hands,” he said, “but we are in the hands of gorgeous nurses!”

INSIDE KOSOVO: “PRETTY REVOLTING”

On May 20 Vieira de Mello’s UN convoy finally entered the province of Kosovo, which appeared to have been emptied of ethnic Albanians. He was relieved finally to be on the most important leg of the trip. “I want to be able to move freely,” he told a reporter. “I don’t want any more speeches.”

8

As the UN vehicles trundled into the province, men at the roadside shouted “Serbia! Serbia!” and offered the three-fingered Serbian salute. The UN team was now vulnerable to attack from three sides; armed Serbs, NATO, and the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) were all engaged in fighting.

The three UN security officials on the trip were not carrying guns, so the team had no choice but to rely on their police escorts for protection. These Serb “minders” were not about to let UN officials move around as they wished. Several times when Vieira de Mello tried to visit villages off the main roads, they refused, claiming the areas were unsafe. As the convoy progressed, the UN team encountered columns of ethnic Albanians fleeing on tractors or on foot. They saw houses, apartments, and shops that had been systematically burned or looted. Anti-Albanian and pro-Serb slogans had been painted on newly vacated buildings. In some areas 80 percent of the homes had been torched. On two occasions the team members themselves witnessed houses being set ablaze.

As his precious few days in Kosovo raced by, Vieira de Mello grew claustrophobic and started to make unscheduled stops. The Serbs, who were anxious to hide the extent of the ethnic cleansing, tried to stop him. After parking the cars at the edge of one village near Urosevac, he broke away from his posse and strode toward what appeared to be abandoned homes and barns. “Sergio, no!” shouted Young. “They could be booby-trapped!” Others chimed in with similar admonitions. But he plowed ahead, knowing that the more he witnessed with his own eyes, the greater his impact would be when he returned to New York. He found homes littered with clothes, bedding, and household goods. Whoever had left the village had fled hastily, leaving behind livestock, family pets, household electronics, photograph albums, and personal legal effects. In one apartment he saw a full pot of tea on the kitchen table, ready to be consumed. “Silent confirmation,” he said.

9

Young had known Vieira de Mello for more than a decade at UNHCR, and she was aware of his reputation for compromising with governments at the expense of refugee rights. Her boss was Dennis McNamara, Vieira de Mello’s frequent foe on policy questions. But the man who was storming into ethnic Albanian homes for proof of war crimes bore little resemblance to the man known as a master diplomat with insufficient regard for human rights.“I had been a protection officer my whole career,” she says,“but there I was saying, ‘Aw, why is he pushing so hard?’ He was far more vigilant about protection than I was.”

He seemed to have come full circle. It was as if his regrets over his own neutrality in Bosnia, combined with his self-consciousness over having forced Hutu refugees back to Rwanda, and his disgust over the way NATO governments had paid no heed to the UN Charter, had resurrected in him the uncompromising righteousness that he had not displayed since his days in Lebanon. If he had once believed that his job was to carry out the aggregate will of powerful governments, he now acted as though he believed that promoting UN principles and protecting the UN flag entailed standing firmly for the advancement of human dignity, even if that required acting in defiance of those governments.

Some members of the UN team felt so unsafe that they began trailing him as if he were ensconced in kryptonite. On one occasion when he stopped the convoy and again charged out of his vehicle, a half dozen members of the team hopped out of their cars and followed him. “People were like, ‘Where is the champ going?’ ‘Where is God going?’ ” recalls Eduardo Arboleda of UNHCR. “They were trailing him like puppy dogs. Until they got halfway down the road and realized he had stopped to take a leak.” The embarrassed UN officials returned to their vehicles with their heads down.

In one town in Kosovo a group of children who had been orphaned by a Serb attack ran toward the UN officials, who realized they had almost nothing to offer. “We could pass out chocolate,” Vandam recalls. “But we knew we would then be abandoning them. I don’t think any of us had ever felt so helpless.” As Sarah Uppard entered her vehicle, one of the children grabbed her hand and refused to let it go. “The kids had no idea what would happen after we left,” remembers Uppard, “and neither did we. It was heartbreaking.”

Vieira de Mello’s unexpected stops and his endless follow-up questions in conversation with Kosovar Albanian civilians caused the convoy to fall behind schedule every day. In one instance, when a group of displaced ethnic Albanians emerged from the trees to speak with him, Chikvaidze contacted a NATO liaison officer to inform him of the delay. Speaking through an interpreter, Vieira de Mello asked the refugees when they had fled, how long they had been hiding, where they were finding food, and whether there were Serb or KLA forces in the vicinity. The discussions dragged on, and Chikvaidze received a telephone call from a UN official at Headquarters who himself had just been telephoned by the office of an enraged secretary-general of NATO. “Oh my god, Mr. Chikvaidze,” the official exclaimed, “NATO is so pissed off that you’re interfering with their work.” Chikvaidze, already conscious of the clock, approached Vieira de Mello, who was in his element conversing with the Kosovars. “They’re terrified in the operations center, Sergio. The secretary-general of NATO is raging mad—” Vieira de Mello, whose back was to Chikvaidze, wheeled around 180 degrees and burst out: “Fuck the secretary-general of NATO. I’m working here.” Chikvaidze was taken aback, as Vieira de Mello rarely let his temper show. “Do you want me to call NATO and pass along that message?” Chikvaidze asked. Vieira de Mello smiled and returned to his task. Every evening at dinner Terry Burke, the team’s chief security officer, would plead with him to do a better job sticking to the schedule. “But, Terry, think of what we’re achieving!” Vieira de Mello would say, adding, “Sit this man down, he needs another glass of wine.”

He was tense on the trip, not so much because of the physical danger but because he knew he needed to bring home fresh evidence of Serbian aggression. If he returned to New York empty-handed, he would miss both an opportunity to raise additional resources to meet humanitarian needs and a chance to remind governments and publics of the UN’s unique value. Between the propaganda he had been fed by Serbian officials before he got to Kosovo and the restrictions the Serbs had imposed on his movements while inside the province, he was not sure he was getting what he needed. Yet despite the pressure and the grimness of the surroundings, he remained playful with his colleagues, treating them to multiple bottles of wine each night. Team members marveled at how he would hold forth at the table tipsily but then, at a designated hour, head upstairs to his room to make his ritual satellite phone calls to New York until the early hours of the morning.

He felt most at ease with his friend Bakhet. The two men did what they had done for more than two decades: They talked about the fate of the UN and bantered about women. Vieira de Mello made repeated references to the beauty of one of the interpreters assigned to him by the Yugoslav foreign ministry. Once when the convoy stopped to interview Kosovo refugees, he summoned Bakhet to him under the guise of discussing highly classified business. When Bakhet asked what was so pressing, he said, “That goddamn minder from the ministry of foreign affairs won’t leave me alone with the translator for one minute! Create a decoy, will you?”

The Serbs had their fun as well. Before the mission began, Kastberg had advised team members that, in light of the food shortages in Kosovo, each team member should bring his or her own supplies. Many members of the delegation brought huge suitcases stocked with bread, dried fruit, chocolate, chamomile tea, and toilet paper. At hotels and guesthouses the Serbian authorities made a point of housing the UN delegates on the top floor. Since NATO attacks had disabled the province’s electricity grid, the elevators did not work, and the Serbs delighted in watching UN team members hauling their heavy stashes of food up successive flights of stairs. Once the UN staff panted their way to their rooms, the Serb officials typically invited them to the local municipal offices where large feasts had been prepared.

On Saturday, May 22, the team’s last full scheduled day in Kosovo, Vieira de Mello was not satisfied with his ability to document life and death behind Serb lines. He instructed Bakhet to take most of the team across the border into Montenegro,

19

while he and a small group would spend an unplanned extra night in Kosovo, making their way to Montenegro a day later than originally scheduled. Young opted for what she called the “cowards’ convoy.” Uppard initially made the same decision but changed her mind the following morning, as she felt she could trust Vieira de Mello to lead what became known as the “cowboy convoy.” Vieira de Mello informed NATO of the split, but it nonetheless very nearly brought disaster. NATO officials had been instructed to look out for a convoy of ten white vehicles, which would be clearly visible from the air. Officials in Brussels did not tell NATO pilots of the change of plan. As a result, he later learned, when the bombers spotted one of the two smaller convoys, they made preparations to strike what they initially assumed was a Serbian military convoy.

On May 24, after gathering additional evidence and testimony during the extra half day in Kosovo, Vieira de Mello’s smaller team crossed out of Kosovo into Montenegro.

10

Bakhet’s group, which had arrived the previous evening in Podgorica, the Montenegrin capital, erupted into cheers when their colleagues reached the hotel. Vieira de Mello knew how to make an entrance, and he had instructed Bakhet to arrange a press conference to coincide with his arrival. Although he had not seen all he had hoped to see, he expected his findings would have broad media appeal.“Just by being here, we don’t have to say, ‘There are reports of . . .’ We will be able to say, ‘We have seen . . .”’ he told Bakhet.

Although he had watched his friend in action for close to two decades, Bakhet was impressed. “The usual UN bureaucrat would have waited to have his press conference in Belgrade, or once he was safe and sound in Geneva or New York,” he recalls.“But Sergio knew that the impact on the world would be so much greater if he delivered his findings breathlessly just when he had ‘escaped’ Kosovo.” At the media event, Vieira de Mello described the “ghost towns” that his team had encountered. He said the evidence was overwhelming and irrefutable.“Everything indicates that there is an attempt to displace, ethnically cleanse, Kosovo,” he said. “In a word, it is pretty revolting.”

11

He was saying nothing new. The mere fact that 800,000 ethnic Albanians had already flooded out of Kosovo was ample proof of Serbian paramilitaries’ ethnic cleansing. Yet his presentation of “eyewitness” findings received prominent play in the press. It stripped those who remained skeptical about Serb brutality of the excuse of “hearsay” or “insufficient information.” Kastberg and Khalikov, lying in their hospital beds in Belgrade, heard snippets of their boss’s press conference on the BBC. Kastberg asked his colleague, “What do you think the Serbs will do to Sergio when he gets back to Belgrade?”

Vieira de Mello knew the risks of returning to the Serbian capital. When his team arrived back on May 26, his first stop was Belgrade Central Hospital, where he checked on his injured colleagues. “Here I was feeling sorry for you, risking kidnapping and NATO bombing for the sake of the UN and the principles of humanitarianism,” Vieira de Mello teased. “But look at these nurses! I clearly chose the wrong car to drive in.” He then made his way to what he knew would be a difficult meeting with the Serbian authorities. Told he would be meeting with Milošević, Vieira de Mello said to Bakhet in the car ride over, “I don’t want to shake hands with that man.” Milošević, in fact, did not show. And when the Yugoslav minister of foreign affairs, Zivadin Jovanovic, the country’s former ambassador in Angola, greeted him in Portuguese, Vieira de Mello interrupted him in English. “Your Excellency, I would prefer not to tell you what I am going to tell you in Portuguese,” he said melodramatically. “It would be an insult to my mother tongue.” He proceeded to launch into the most impassioned and rigorous defense of the core UN right to human security and dignity that Bakhet had ever heard. “Sergio was so outspoken and so undiplomatic, and yet so professional,” Bakhet recalls. “It was as if the UN Charter was speaking through a person.” As the men drove back to their hotel, Bakhet could only shake his head. “You must have a death wish, Sergio,” he said.

When the two men walked into the lobby of the Belgrade Hyatt, they saw Zeljko “Arkan” Raznatovic, Serbia’s most notorious warlord, who gave them the finger. Deciding it best to remain out of view, they proceeded directly to the elevators. Arkan sat down in the Hyatt bar with his wife, popular Serbian folksinger Ceca, and their two children, who were dressed primly as if for church. Relieved to be out of Kosovo, Kirsten Young was having a drink with several UN team members, and she shuddered when she saw Arkan at the adjacent table.

When Vieira de Mello reached his hotel room, he ordered room service and turned on CNN. There he saw Christiane Amanpour deliver a shocking leaked exclusive: Louise Arbour, the UN war crimes prosecutor in The Hague, had indicted Milošević for war crimes and crimes against humanity. It was the first time a sitting head of state had ever been indicted by an international tribunal. Vieira de Mello was taken aback by the timing of the indictment. Frank Dutton, Arbour’s war crimes investigator who had accompanied the mission under cover, had assured him that no indictment would be issued while they were in the region.“Why did they do this now?” Vieira de Mello shouted at Bakhet. “Why not at any other time within the last five or six years? Why not tomorrow? What if we are held hostage here?” Vieira de Mello, the same man who kept a poster of Bosnia’s MOST WANTED war crimes suspects on the wall in his office in New York, wanted to see Milošević behind bars. Yet he felt that the security of his mission had been jeopardized, and the UN had revealed itself to be disorganized and dysfunctional. Few of the UN team members slept soundly that night. Vandam of the WHO opted to sleep in his clothes.“I decided that if they were going to kidnap me in the middle of the night, I would prefer not to be taken naked,” he recalls.

The UN team was scheduled to drive back to Croatia the following day, but Vieira de Mello pushed forward the time of the UN departure, opting to leave at the crack of dawn. Before leaving, he went to Belgrade Central Hospital and escorted Kastberg and Khalikov to the airport, where they were put on a plane back to NewYork. He also pulled Dutton aside and asked him for the notes, film, and videotapes he had collected.“The Serbs will be much less likely to search me than you,” Vieira de Mello said. The same man who had once befriended war criminals like Ieng Sary and Radovan Karadžić and agreed that his biography might best be entitled My Friends, the War Criminals was now doing his part to ensure that Balkan war criminals faced justice. After burying a bounty of evidence beneath his socks and T-shirts, he crossed the border from Serbia into peaceful Croatia and breathed an audible sigh of relief.“You don’t think NATO can miss this badly, do you?” he asked Bakhet. Later that day Arbour formally announced Milošević’s indictment. The Serbian dictator would be arrested and transferred to The Hague two years later. The leak had proven harmless.

As Vieira de Mello drove with Bakhet into Zagreb, he complained that officials from the Croatian foreign ministry were likely waiting for him at the hotel. “I’ve had enough of meetings,” he said suddenly.“Let’s forget the Croats and go get a proper meal.” The two men ducked into a restaurant Vieira de Mello knew from his days working for UNPROFOR five years before. They talked about all topics under the sun except Kosovo. When they arrived at the airport to catch their flight to Switzerland, they found a panicked UN staff and irritated Croatian officials. Vieira de Mello beckoned Dutton over to his suitcase, where the war crimes investigator retrieved his evidence.

Team members flew from Zagreb to Zurich, where they stayed at an airport hotel. There Vieira de Mello found a fax awaiting him from his assistant, Fabrizio Hochschild, who had read a wire story describing the UN press conference in Montenegro. Hochschild, who was loyal to Vieira de Mello but also often sharply critical, wrote that his boss’s rebuttals of Serbian falsehoods “were courageous and made us all feel proud.”

12

UN Headquarters in New York had had a funereal feeling in March, when NATO went to war unilaterally, but Vieira de Mello’s mission had lifted spirits. The Security Council may have been bypassed, but by offering the first independent eyewitness proof of the ethnic cleansing, UN officials felt they had proven the organization mattered.

The exhausted UN team members gathered in the hotel garden for drinks and dinner, but their leader retired to his hotel room. As his colleagues released the tension of the previous two weeks with alcohol and laughter, Vieira de Mello stood at his hotel window looking down at the courtyard, clutching a phone to his ear and waving occasionally.

When he returned to Headquarters in New York, he became the first humanitarian official ever to be called to testify before the UN Security Council. On June 2, all eyes were on him, as he had gone where even NATO generals had not dared to go. He began his remarks by commending the Yugoslav health authorities for caring for Kastberg and Khalikov, but then he delved quickly into a detailed discussion of Serb ethnic cleansing. His team, he said, had enjoyed access that “was more than expected, but less than requested.”

13

The Serbian authorities had limited the team’s movement by citing security concerns that were “often neither understandable, nor convincing.” Nonetheless he had seen enough of the province to know that it was a “panorama of empty villages, burned houses, looted shops, wandering livestock, and unattended farms.”

14

Since the bulk of the mission’s time had been spent in Serbia, he had plenty to add about the destruction caused by NATO bombing as well. He reported that civilians would be suffering for many years the effects of the environmental damage, psychological trauma, and destruction of essential services, such as electricity, health, communications, and heating. Although his presentation was evenhanded, he had led with a discussion of Serb violence, and it was these comments that captured global news headlines, as he knew they would.

His daredevil mission had not brought radically new information to light, but he had highlighted civilian suffering and reasserted the UN’s independent voice. He had shown as much to himself as to anyone that the UN was prepared to stand up for the victims of ethnic cleansing, while also standing up for itself.