Twenty-two

POSTMORTEM

RETURNING TO THE CANAL

The night of August 19 the UN officials who had survived the Canal Hotel bombing gathered in their Baghdad hotels. Many were so paralyzed by shock that they had not yet cried. But when they walked into the hotels where they slept and saw colleagues whose fates they had not known, the events of the day hit them and they wilted. Often it was only when they reached their rooms and looked in the mirror that they realized they were covered in blood. In many cases the blood was not their own. Information on the dead and injured was hard to come by, but surviving staff were under the impression that anybody who had been in, near, or under Vieira de Mello’s office on the third floor had not made it.

Hearsay competed with facts all night, but the list of the known dead and gravely wounded was long. Many of the deceased had been killed instantly, and their families were notified. For others, like Lyn Manuel, Vieira de Mello’s Filipina secretary, and Nadia Younes, his Egyptian chief of staff, rumors of sightings persisted well into the evening. Finally both the Manuel family in Queens and the Younes family in Cairo were notified that neither woman had survived the blast.

Those listed as killed, in addition to Sergio Vieira de Mello, the UN Special Representative of the Secretary-General, were:

United Nations

Reham al-Farra, 29, Jordan, spokesperson

Emaad Ahmed Salman al-Jobory, 45, Iraq, electrician

Raid Shaker Mustafa al-Mahdawi, 32, Iraq, electrician

Leen Assad al-Qadi, 32, Iraq, information assistant

Ranillo Buenaventura, 47, Philippines, secretary

Rick Hooper, 40, United States, political officer

Reza Hosseini, 43, Iran, humanitarian affairs officer

Ihssan Taha Husain, 26, Iraq, driver

Jean-Sélim Kanaan, 33, Egypt/France, political officer

Christopher Klein-Beekman, 32, Canada, program coordinator for United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF)

Marilyn “Lyn” Manuel, 53, Philippines, secretary

Martha Teas, 47, United States, manager of the UN Humanitarian Information Center

Basim Mahmood Utaiwi, 40, Iraq, security guard

Fiona Watson, 35, United Kingdom, political affairs officer

Nadia Younes, 57, Egypt, chief of staff

Others

Saad Hermiz Abona, 45, Iraq, Canal Hotel cafeteria worker

Omar Kahtan Mohamed al-Orfali, 34, Iraq, driver/interpreter, Christian Children’s Fund

Gillian Clark, 48, Canada, child protection worker, Christian Children’s Fund

Arthur Helton, 54, United States, director of peace and conflict studies at the Council on Foreign Relations

Manuel Martín-Oar Fernández-Heredia, 56, Spain, assistant to the Spanish special ambassador to Iraq

Khidir Saleem Sahir, Iraq, driver

Alya Ahmad Sousa, 54, Iraq, consultant to the World Bank Iraq team

Secretary-General Annan was not known for allowing people to get close to him, but he spoke of Vieira de Mello and Younes as if they were exceptions. He had known Vieira de Mello since their days together in UNHCR in the 1980s, and Younes had been his chief of protocol for three years in New York. As he stopped briefly at Stockholm’s airport en route back to New York, he was less diplomatic than usual. “We had hoped that by now the Coalition forces would have secured the environment for us to be able to carry on ... economic reconstruction [and] institution building,” Annan said. “That has not happened.” Ever careful, though, he added, “Some mistakes may have been made, some wrong assumptions may have been made, but that does not excuse nor justify the kind of senseless violence that we are seeing in Iraq today.”

Annan did not consider pulling the UN out. “The least we owe them is to ensure that their deaths have not been in vain,” he said. “We will persevere.” The UN had operated in Iraq for more than twelve years without being attacked. “It’s essential work,” he said. “We are not going to be intimidated.”

1

Annan’s line echoed that of U.S. officials in Iraq and Washington.

On August 21 Kevin Kennedy, the former U.S. Marine and UN problem-solver, landed back at Baghdad airport in Iraq. Although he had lost Vieira de Mello and several other close UN colleagues, he knew that he was in a more stable psychological state than those who had actually lived through the attack, who were in no condition to manage arranging the evacuation of the wounded and the deceased.

Kennedy walked across the tarmac, where some fifty shell-shocked UN personnel were gathered in advance of being evacuated to Jordan. Carolina Larriera approached him, frantic. “I’m not getting on the plane to Amman,” she said.“They are making me leave. I want to go on the plane with Sergio.” The Brazilian government had dispatched an air force 707 to Baghdad to collect his body. Kennedy had been told that Annie would be on the Brazilian plane. He called Lopes da Silva. “Carolina wants to fly with Sergio,” he said.“What the hell do we do?” Lopes da Silva was decisive. “Get her on that plane to Amman,” he said. “Get her out of here.” Kennedy assured Larriera that she would be able to meet the Brazilian plane in Amman, and she was steered onto the UN plane with the other bomb survivors.

Most of the families of the deceased had begun making burial arrangements. Lyn Manuel’s grief-stricken family in Woodhaven, Queens, was no exception. Manuel’s husband of thirty-four years and her three children had already held a private memorial service at their home and were awaiting the return of Manuel’s body for the funeral. At 3 a.m. on August 21, two days after the bombing, Eric and Vanessa, Manuel’s two youngest children, aged twenty-five and twenty-nine, were sitting in their living room telling stories about their mother. The phone rang, and Eric answered it. The line was filled with static. Eric’s heart stopped. "Hello,” the voice said. “Hello, Eric. It’s Mom.” “What?” he said. “It’s Mom,” she answered. “Eric, it’s Mom.” Seeing the look on her brother’s face, Vanessa ran upstairs and picked up the other phone. Lyn Manuel, whom UN officials in Iraq had listed among the dead on August 19, was calling from a U.S. Army clinic outside Baghdad. She had regained consciousness next to a patient with a cell phone. Manuel panicked when she heard the voice of her daughter, who lived in Hawaii and had not planned a trip to Queens. “Is everybody okay?” Manuel asked. Her son and daughter assured her that everything was fine and did not tell her about the mix-up. Instead, they wished her a happy fifty-fourth birthday and told her they loved her. After hanging up, they collapsed in sobs of joy.

As the bomb survivors prepared to fly out of Baghdad, an FBI team established a kind of checkout procedure by which UN staff left their names and contact details. Many of the UN officials questioned were hostile to the FBI, which they saw as yet another offshoot of the U.S. occupation, but most agreed to make themselves available for future questioning. The FBI inquired particularly about the UN’s Iraqi staff, and two Iraqis who worked for the UN were detained and interviewed repeatedly in the days that followed. The United Nations did little to keep survivors and family members informed of the progress of the investigation, beyond setting up a confidential Web site and a Listserv (iraqinvestigation@ohchr.org) through Vieira de Mello’s office in Geneva. The site was barely used.

On August 22, the day after Larriera and other survivors were shepherded out of Baghdad, the Brazilian government’s 707 arrived to collect Vieira de Mello’s casket. The plane would then make its way to Geneva, where it would collect Annie, Laurent, Adrien, and their guests, en route to Brazil. William von Zehle, the Connecticut fireman who had kept Vieira de Mello company in the shaft during his last hours, had written a letter to Annan in which he described fragments of what Vieira de Mello told him under the rubble. Von Zehle distinctly recalled the dying UN official saying, “Don’t let them pull the mission out.”

On the tarmac at the coffin ceremony, Benon Sevan, the highest-ranking UN official on the scene, quoted from von Zehle’s letter in urging a continued UN presence:

Sergio was fully committed to the United Nations until his last breath. Even under the most extreme pain, pinned down under the rubble of his office, he said ... "Don’t let them pull the mission out.” ...

Our beloved Sergio . . . Bowing before you at this very difficult hour, I assure you that no heinous act of terrorism will deter us from carrying out the noble tasks entrusted to us in the service of the United Nations. We will resume our activities as of tomorrow and continue your legacy.

2

Those closest to Vieira de Mello were skeptical that, having so soured on the ineffectual UN mission, he would have made such an appeal. But Annan and the press henceforth made frequent reference to his alleged last wishes. “His dying wish was that the United Nations mission there should not be pulled out,” Annan declared. “Let us respect that. Let Sergio, who has given his life in that cause, find a fitting memorial in a free and sovereign Iraq.”

3

The media tried to provoke Annan into blaming the Bush administration for going to war in the first place, but the secretary-general remained politic. “We all know the military action was taken in defiance of the Council’s position,” he said. “Lots of people in this building, including myself, were against the war, as you know, but I think we need to put that behind us. That is something for historians and political scientists to debate.” The UN’s focus needed to be on the future, as “a chaotic Iraq is not in anyone’s interests—not in the interest of the Iraqis, not in the interests of the region, and not in the interest of a single member of this organization.”

4

Vieira de Mello’s family was divided over where he should be buried. A cosmopolitan, he had not lived in Brazil since he was a boy, but his pride in his nationality had intensified over the years. His mother, Gilda, was desperate for him to return home. Annie proposed that he be buried in her family’s plot in a cemetery near Massongy. In the end the Swiss government extended an invitation for him to lie in rest at Geneva’s exclusive Cimetière des Rois, or Cemetery of the Kings, the small, elegant gated cemetery where Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges was buried and which, eerily, Vieira de Mello and Larriera had visited twice that spring. André Simões, his thirty-seven-year-old nephew, explained the decision to a Brazilian journalist: “His sons said that, as their father was always absent, at least now they would be near him.” Simões’s voice faltered. “It is understandable.”

5

Carolina Larriera did not manage to reach Vieira de Mello before he was buried. After traveling to Amman, she attempted to get a connecting flight to Rio de Janeiro in time for the memorial service. But officials in New York were worried that if she and Annie converged, there would be an ugly scene. With a cold formalism that was excessive even by the standards of a gargantuan bureaucracy, they told Larriera that staff rules dictated that the UN would pay only for her to return to her home country of Argentina. She would have to make her own way to Brazil. Larriera flew from Amman to Paris to Buenos Aires and on to Rio de Janeiro, but by the time she arrived in Rio five days after the bombing, still in the torn and bloody skirt she had been wearing the day of the attack, her partner’s casket was gone. The Brazilian 707 had left for Geneva earlier in the day.

Thomas Fuentes, the head of the FBI’s Iraq team, had gathered a wealth of evidence at the crime scene. In the World Trade Center bombing of 1993 and the Oklahoma City bombing of 1995, the vehicle identification number had led the FBI to the terrorists. In Baghdad the FBI had that number, as well as the license plate number and the hand of the bomber.

6

But for all of the encouraging early clues, the investigation quickly stalled. Because Muslim burials typically occur within twenty-four hours of death, Iraq did not have

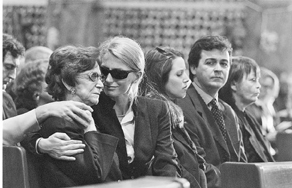

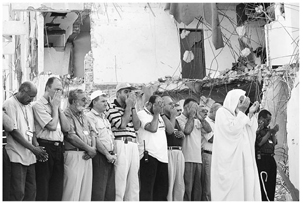

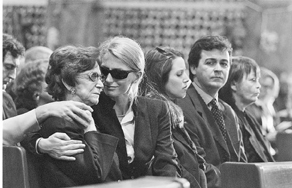

Left to right: Gilda Vieira de Mello, Carolina Larriera, Renata and André Simões, and Sonia Vieira de Mello at a memorial mass in Rio de Janeiro seven days after the Canal Hotel attack.

refrigerated morgues. The only facility available to store the UN’s deceased and the body parts of the bomber had been the air-conditioned morgue at the U.S. base near Baghdad International Airport. But even in the American morgue the temperature often reached 100 degrees because of electricity shortages and overcrowding. As a result, the hand of the bomber, which had seemed a promising source of fingerprints, had begun to decompose. Hoping to preserve it, Fuentes got permission to have it flown back to the United States with the three deceased Americans. But by the time the hand reached the FBI laboratory in Quantico, Virginia, the forensic analysts were able to retrieve only partial fingerprints. And the FBI analysts later learned that Saddam Hussein’s Iraq had never created a fingerprint data bank. Thus, Fuentes had no Iraqi records with which to compare the bomber’s markings. Equally frustrating, he established that the Kamash truck had been made in Russia and purchased by the Iraqi government, probably back in 2001. But despite having its manufacturing and license plate numbers, the FBI was unable to find the vehicle records kept by the Iraqi government—they were presumed to have been looted.

UN senior staff in New York left the criminal investigation to the FBI and focused on the future of the UN in Iraq. Heated debates commenced about what had become known as the UN’s “perception problem,” the Iraqi belief that the UN was a stooge of the Coalition. Before any long-term decisions would be made, senior staff agreed on the necessity, in the words of one Iraq Steering Group debate,“to reduce the size of the ‘UN target.’”

7

International staff who had survived the bomb were required to take fourteen days of leave, and most would not be sent back.

29

The four thousand Iraqi nationals who served the UN were also granted leave, though they were instructed to take it inside Iraq.

8

Ghassan Salamé flew to New York, his first trip back since he had accompanied Vieira de Mello to brief the Security Council in July. He told the secretary-general and other senior UN staff that the UN was caught in a catch-22:“If we do not accept increased protection from the CPA, we would be reckless,” he argued. “But if we accept their security, we will reinforce the perception that we are ‘hand in glove’ with the CPA.”

9

The most vocal advocate of withdrawing all UN staff was Kieran Prendergast, the head of the Department of Political Affairs, who was devastated by the death of Rick Hooper. He did not believe that the UN was doing enough good to justify its continued presence in Iraq. “The UN has not been able to establish a differentiated brand,” he argued.“If a fortress is required to ensure security, why be there?”

10

He urged his colleagues to ask a simple question of the mission the UN was undertaking in Iraq: “Is it worth risking the life of one individual?”

11

Staying, he argued, was nothing more than “a suicidal mission.”

12

The downsized UN team that remained in Iraq did little beyond concentrate on securing themselves. Most staff were especially frightened in their hotels at night, and some, Lopes da Silva wrote to UN Headquarters,“were displaying signs of irrational behavior, including requests to carry firearms.”

13

The UN posted twenty-six additional security staff to Baghdad, a dramatic expansion of the tiny squad that had been overwhelmed all summer. Coalition intelligence officers, who had tended to shun UN requests for information on the insurgency prior to the bomb, were suddenly forthcoming. On September 1 they warned the UN that they had intelligence that three heavy sewage trucks had disappeared and one of them might be used to target the UN between September 5 and 10.

14

On September 2 a report

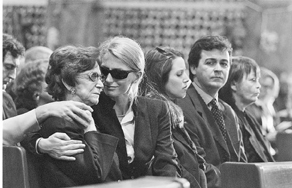

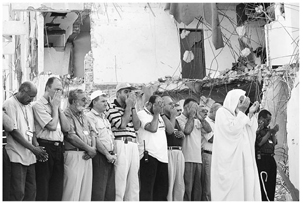

UN staff in Baghdad at a prayer memorial, August 30, 2003.

from Erbil, in northern Iraq, said that two vehicles marked UN-HABITAT were missing and might have been stolen and packed with explosives.

15

Later UN officials picked up a rumor in Baghdad that U.S. forces were the ones who had attacked the Canal Hotel so as to drive the UN from Iraq and, in the words of one UN Iraqi staffer, “keep government to themselves.”

16

Although no evidence surfaced to bolster this theory, the Bush administration’s well-established hostility to the UN made it a popular one in the Middle East and in Vieira de Mello’s native Brazil.

Since the Canal Hotel had been reduced to rubble, Lopes da Silva, Kennedy, and others scouted Baghdad for other properties. The Coalition again offered to house UN staff inside the Green Zone, but Kennedy declined. He and Lopes da Silva soon concluded that it would be easier to fortify the Canal complex and consolidate UN staff there than to find a new, safe space. The Canal was, Kennedy said, “the best solution in a worst case scenario.”

17

Containers where UN staff would now work and sleep were flown in from Kuwait and set up on the Canal grounds near the ruins of the hotel. UN staff began to refer to the Canal complex as “Fort Knox.” The Coalition replaced the antiaircraft platoon outside the premises with a reinforced U.S. rifle company. But because UN staff remained concerned about the signal such a partnership sent, the UN went back to reviewing bids from private security firms that might guard the vulnerable premises.

18

All of the security precautions that had not been taken—or that had been taken halfheartedly—before August 19 now got full attention. UN security officials in Iraq kept a constant watch on the mission’s staff lists, gathering not only names but blood types, contact details, radio call signs, and cell phone numbers. They created an inventory of available resources: radio and communication equipment; protected vehicles; flak jackets; helmets; Mylar plastic film for the windows; and ballistic blankets that could shield doors, windows, and people. The security staff went about setting up emergency medical facilities, a security operations room, and new external wall barriers at the Canal. They expanded the number of bunkers meant to shelter staff during mortar attacks and pasted luminescent arrows on the ground between the containers to guide staff to the exits in the event that an attack caused darkness or occurred at night.

19

Kennedy urged his bosses in New York to appeal to UN member states to replace the lumbering UN transport planes that were so vulnerable to ground fire with military aircraft that could detect and neutralize surface-to-air-missiles.

20

In the meantime the UN varied its flight times and stopped publishing its timetable. It also repainted part of its fleet of vehicles from navy and orange back to plain white and removed the UN decals.

21

As the weeks passed, and as insurgents unleashed a wave of fresh attacks against a broad range of Iraqi and international targets, it became clear that the attack on the Canal Hotel had marked a turning point in Iraq’s history. Colonel Mark Calvert, the squadron commander who set up the security cordon on August 19, recalls, “We had a lot of NGO support up until that time, people flooding in wanting to help, bringing capabilities that combat forces don’t have. When that bombing took place, it had a devastating impact on reconstruction and development, which was exactly what the terrorists wanted.” Security unraveled for civilians everywhere. On August 29 a car bomb outside the Imam Ali Mosque in Najaf killed ninety-five people, mostly Shiite pilgrims.

On September 2, acting on advice from the Security Management Team in Baghdad, Tun Myat, who ran the UN security department in New York, recommended that the UN in Iraq move to Phase V, the highest security level, and withdraw all its international staff from Baghdad.

22

Secretary-General Annan, the only UN official with the authority to order an evacuation of staff, rejected the recommendation, saying it would send the wrong signal to terrorists. On September 13 a ninety-minute gun battle erupted outside the perimeter of the Canal Hotel complex. The staff felt intensely vulnerable, but Annan remained determined to show the UN flag. “We didn’t stay in Iraq to do anything,” recalls one UN official. “We stayed in Iraq to show we were staying.”

23

Senior UN staff in New York were naturally caught up in a blame game that intensified with time. All-knowing analysts in the United States, Europe, and the Middle East pointed to the ominous warning signs that Vieira de Mello and other UN officials missed. The consensus view was that the UN had been naïve in viewing itself as untouchable and in failing to appreciate just how hated the organization was in Iraq, owing to sanctions, weapons inspections, and (thanks to Vieira de Mello’s high-profile intermediary role) its association with the Governing Council. Just as people had speculated as to what the Jordanian government had done to earn the ire of the August 7 attackers, everybody seemed to have a theory as to why the UN had been so savagely struck.

UN officials in New York walked around like zombies for a month and then gathered on September 19 for a large commemoration in the giant General Assembly hall. Annan spoke of his “irreplaceable, inimitable, unforgettable friends.” “When we lost them, our Organization also suffered another loss, of a different kind: a loss of innocence for the United Nations,” he said. “We, who have tried from the beginning to serve those targeted by violence and destruction, have become a target ourselves.”

24

The August 19 attack, many noted, was the UN’s “9/11.”

The day of the memorial service, the UN flag at the Canal Hotel was raised to full mast for the first time since the attack. UN staff in Baghdad were impatient for guidance from headquarters and warned New York: “If the UN is to remain in Iraq, and particularly if it is to re-engage in political affairs, the Organization must assume that it will be the victim of more attacks.”

25

At 9 a.m. on September 20 Aquila al-Hashimi, the Shiite Muslim who had helped arrange Vieira de Mello’s meeting with al-Sistani and one of three women on the Governing Council, was ambushed by nine gunmen on a residential street two blocks from her home in western Baghdad. Guarded only by her brothers, who did not wield weapons, she was shot in her abdomen and died five days later. It was the first assassination of a member of Iraq’s Governing Council. Prior to her murder, Iraqi politicians were not given Coalition bodyguards or police escorts, disproportionately endangering independents on the council who did not have their own militias.

26

The insurgents were not finished with the UN. On September 22 at 8:04 a.m., a man driving a small gray Opel sedan approached the back gate of the Canal compound, where he was told by Iraqi guards that he would have to park in the dirt lot across the street, where Iraqi UN staff and the guards themselves parked. In accordance with the UN’s post-August 19 heightened security screening procedures, an Iraqi guard approached the Opel and asked the driver to open his trunk. When he did, the driver detonated two sets of explosives—one in the trunk and one that he was wearing as a belt. The blast blew the car in half, killing the Iraqi guard and the bomber instantly and injuring nineteen others. Iraqi guards complained that they were wearing bull’s-eyes, being forced to guard buildings without training, weapons, or flak jackets, while well-fortified American soldiers avoided such hazards. “We are just like human shields for the Americans,” said Haider Mansour al-Saadi, twenty-two, a guard who received shrapnel wounds to his hand and leg in the blast.

27

The attack that killed Vieira de Mello and twenty-one others the month before had occurred at the end of the day. Amid the frenetic focus on rescue and identification, the UN Security Management Team in Baghdad had not had the chance to recommend a full staff withdrawal before Annan had announced that the UN was staying. But this second attack on the UN occurred in the morning, Iraq time. By the time senior staff in New York reached their offices, the security team had already cabled New York with the “unanimous recommendation” that the secretary-general declare Phase V for all of Iraq.

28

Aware that local staff were often forgotten in New York, the security staff stressed that “the security and safety of national and international staff members must be considered on par.”

29

Annan, however, ignored the advice of his Iraq team and that of his senior staff (all but one of whom voted to evacuate Iraq), and again rejected the recommendation to pull out. The staff in Baghdad were incredulous.

The insurgent attacks on soft targets (which only began with the bombs at the Jordanian embassy and the UN) continued. On September 25 the hotel housing the staff of NBC News was hit, a sign that the media had become a target. Two days later three projectile rockets were fired at the Rashid Hotel inside the Green Zone. This marked the first time a civilian target inside the Green Zone had been hit. On October 9 a Spanish diplomat was assassinated. On October 12 the Baghdad Hotel, which housed American contractors and Governing Council members, was bombed, killing eight and wounding thirty-eight. On October 14 the Turkish embassy was struck. On October 26 the Rashid Hotel, where U.S. deputy secretary of defense Paul Wolfowitz was staying at the time, was hit again, killing one and wounding fifteen. And on October 27, the first day of Ramadan, in a devastating coordinated assault, four bombs were detonated simultaneously, including one at the Baghdad headquarters of the International Committee of the Red Cross, which killed thirty-four and wounded two hundred. Three days later, after the Red Cross announced it was leaving, Annan finally declared Phase V, and all UN international staff were at last withdrawn from Baghdad.

The secretary-general launched two investigations into staff safety and security surrounding the Canal Hotel attacks. The first, chaired by former Finnish president Martti Ahtisaari, produced a short report nine weeks after August 19. The second, chaired by Gerald Walzer, the former deputy high commissioner for refugees who had been the one to give Vieira de Mello a flak jacket as his going-away present from UNHCR, yielded a 150-page report, with six volumes of supporting documents, and was delivered to Annan on March 3, 2004. After receiving the Walzer report, which described the UN security system as “dysfunctional,” the secretary-general called for the resignation of Tun Myat, the UN security coordinator, who complied. Additionally, the UN took disciplinary action against Paul Aghadjanian, the chief administrative officer, and Pa Momodou Sinyan, the building manager, who had failed to ensure that the windows were coated with Mylar or that the concrete wall was completed. Since Lopes da Silva had been the designated security official, Annan demoted him, stripping him of his assistant secretary-general rank and barring him from taking UN posts with security functions.

30

Louise Fréchette, the deputy secretary-general who had chaired the Iraq Steering Group in New York where security was discussed, offered her resignation to Annan, but he refused it.

UN staff and bomb survivors felt let down by the secretary-general. At no time did he delve into the UN’s more fundamental failings on Iraq—failings that had far broader implications for the future of the organization than the absence of blast-proof plastic sheeting for the windows. Why had Annan so eagerly accepted the Security Council’s summons to go to Iraq? Why did he send his finest staff to enforce an almost nonexistent mandate? Why, after the attack, had he chosen to keep UN staff in harm’s way, even though they were not performing vital tasks? What would it take for the UN secretary-general, in fact, to learn to say no to powerful countries?

Friends and family of those attacked on August 19 speculated that Annan found the Iraq experience so searing that he could not face it. Many thought he and Fréchette had staged a phony resignation scene even though they had no intention of instituting accountability at the highest levels. Some were furious that Annan himself did not step down. They blamed him for allowing junior staff to take the fall for what were above all leadership failures. “If you were in the room with Kofi Annan, with Iqbal Riza [his chief of staff], and with Tun Myat,” notes one UN official, “you wouldn’t see Tun Myat as responsible for anything.”

And the heavyweight countries on the Security Council seemed to care no more about UN staff in the aftermath of the bomb than they had in May when they sent the UN to Iraq in the first place. When Rafiq Hariri, the former Lebanese prime minister, was murdered in February 2005, the UN Security Council leaped to commission an investigation into his murder that cost around $50 million per year. But when it came to the murder of UN staff, the Security Council seemed indifferent. As the violence in Iraq escalated, the memory of the UN attack faded.

SURVIVORS

Gil Loescher, the only person who survived the meeting in Vieira de Mello’s office, was flown to Landstuhl, Germany, and given a 25 percent chance of making it. Building upon Andre Valentine’s primitive but lifesaving sawing procedure, the doctors in Germany amputated both of Loescher’s legs above the knee. On September 2 Loescher regained enough consciousness to begin mouthing words and asking about the pain in his legs. But only in late September, more than a month after the attack, did he realize he had been permanently handicapped. “Now, I have no knees, right?” he asked his daughter.

For more than a year after the attack, tiny shards of glass would work themselves free from his skin.

31

His face was badly scarred, and he initially had no use of his right hand, but he made remarkable progress, reacquiring the use of his hand and mastering computer-assisted prosthetic legs. He returned to the book he had been writing on protracted refugee crises, and in 2006 he managed to travel to the northern Thai border to interview Burmese refugees. In one of the camps, he made a special point of trying to visit an out-of-the-way care center for disabled refugees run by Handicap International. But after wheeling himself across the camp, he found that the facility had been built atop a steep mud bank that his wheelchair could not ascend. Resigned to turning back, he suddenly saw five Burmese faces peering down at him from the top of the bank. The Burmese, each of whom had a wooden prosthetic leg, made their way down the bank, raised Loescher’s wheelchair onto their shoulders, and carried him up the hill.

Loescher divides his existence into his “first life” and his “second life.” He says that on occasions when he is tempted to feel sorry for himself, he thinks about all that was lost on August 19, including his close friend Arthur Helton. He also thinks about refugees.“My whole career I have been visiting refugee camps, and without realizing it, I was getting tutorials about resilience. If they can bounce back, I certainly can.” He says he has his blue periods, but he does not ascribe those to his injuries. “There is plenty to feel blue about in the world,” he says.

While Loescher lives with the visible scars of the attack, Vieira de Mello’s bodyguards endure the ghosts of August 19. Gaby Pichon, the French close protection officer who was just twenty feet away from his boss when the bomber struck, says his dreams are haunted by his failure to save the man entrusted to him. “Why him and not me?” he says. “I have flashbacks. It is not like a TV that you can turn off. I don’t have a remote control.” Gamal Ibrahim, the Egyptian who guarded Vieira de Mello in East Timor and for the first two months in Iraq, removed himself from the UN’s close protection roster after the bomb and transferred to the canine unit.“I never want to get close to anybody I’m protecting again,” he says. “Working with a dog is fine for me.” Alain Chergui, who on Vieira de Mello’s insistence had taken leave five days before the bomb, is convinced he would have found a way to save his boss. He cannot forgive himself for being absent when it mattered most, for Vieira de Mello, for the UN, and for the world. “If I weren’t married,” he says, “I would probably be dead now. I would have shot myself maybe. Protecting Sergio was what I was there to do; it was all I was there to do.”

Lyn Manuel, fifty-eight, is back living in Queens and working at UN Headquarters. She has undergone four plastic surgeries on her face and five on her injured left eye, and her recovery is nothing short of miraculous. But, because she has lost vision in the left eye, and her good eye has begun to falter, she plans to retire in 2008. She knows that, for many UN officials, she is a walking reminder of the dead.

Jonathan Prentice and Carole Ray, Vieira de Mello’s special assistant and secretary, who had gone on leave with Chergui just days before the bomb, live with the knowledge that their replacements, Rick Hooper and Ranillo Buenaventura, died at desks that they normally occupied. After their boss’s death, they remained at the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights in Geneva partly as a way of staying close to his memory. “I’m not sailing quite so close to the sun as I did when I rode Sergio’s coat tails,” Prentice says. “But maybe that’s not as important as I once thought it was, or as Sergio thought it was.”

Two of Vieira de Mello’s closest friends in the UN, Omar Bakhet and Dennis McNamara, had been outspoken, unconventional staff members throughout their tenures with the organization. On many occasions when they got into trouble with their higher-ups, Vieira de Mello had intervened on their behalf. The year after the Canal attack, Bakhet left the UN, and today he advises the African Union on how to restructure itself. McNamara, who had achieved the rank of assistant secretary-general, retired in 2007 and currently works as a consultant on how to protect civilians in African conflict areas. Although they had sparred constantly, McNamara and Vieira de Mello had worked together in Geneva, Cambodia, Congo, Kosovo, East Timor, and Iraq. “Had things gone differently,” he says, “Sergio and I would surely have ended up in some other godforsaken place together.” Fabrizio Hochschild, Vieira de Mello’s special assistant in Geneva, New York, Kosovo, and East Timor, shared his mentor’s taste for working in the field, but he also tried to do what his boss and friend had never managed: put family first. The father of three children, Hochschild returned to Geneva from Tanzania after the Baghdad bomb and became director of operations for Louise Arbour, Vieira de Mello’s successor as UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. He took periodic trips to the world’s hot spots but tried to remain close to home, even learning how to become a manager.

Martin Griffiths, who became Vieira de Mello’s friend late in life, had left the UN in 2000 to run the Henry Dunant Center for Humanitarian Dialogue in Geneva, where he serves as a mediator among war combatants. Glad to be free of the shackles of UN red tape and politicking, he believes Vieira de Mello was himself on a path toward reconciling his personal and professional ambitions. “Sergio had devoted his life to the ideals and organization of the UN. And the countries in it had failed and disappointed him just as much as they had enriched and glorified him,” Griffiths observes. “The thing about Sergio was his youth. He still wanted what youth wants. He was getting more and more impatient about the half-measures he had. His tragedy was not his death—that was our tragedy. His tragedy was that he never finally arrived at that state of equilibrium that adults call happiness.”

Annie Vieira de Mello, who still lives in Massongy, remains very close to her sons, Laurent and Adrien. Both in their late twenties, the two men have deliberately eschewed the public spotlight. Laurent works as an engineer in Zurich, while Adrien, who graduated with a degree in geography, works in construction and building design in Geneva. With all that has been written and broadcast about their father, they have gained a deeper understanding of why he was so often absent during their childhoods.

Carolina Larriera is the only person who both survived the bomb and lost a loved one. Afflicted by a severe case of post-traumatic stress syndrome, she left the United Nations and moved to Rio de Janeiro. There she and Vieira de Mello’s mother, Gilda, attempted to raise his profile in Brazil, a country that has become acquainted with him only in death. They also pushed the UN to investigate the attack and the failed rescue effort. Larriera spoke with the FBI, tracked down William von Zehle, and along with Timorese foreign minister José Ramos-Horta, visited Gil Loescher in the U.K., but she made little headway.

In early 2004, after she and Gilda collected a bagful of sand from Vieira de Mello’s favorite spot on Ipanema beach in Rio, she flew to Geneva, where she visited the cemetery they had discovered together, and she sprinkled the Brazilian sand upon his grave. Later that year she reenrolled in the master’s degree program at the Fletcher School, which she had been slated to start the month of the attack. In 2006, after graduating from Fletcher, she began teaching international relations at Pontificia Universidade Cátolica in Rio, and the following year she took a job running the Latin American office of an organization that lobbies for access to medicines for the poor.

Gilda Vieira de Mello, who was eighty-five at the time of the attack, remains mentally alert, physically fit, and feisty. She had long declared herself too old to fly, but in 2004 she made an exception, taking one last foreign trip to Geneva to attend the ceremony commemorating the one-year anniversary of the Canal Hotel attack. She remains in deep mourning, her apartment a virtual shrine to her deceased son. She and Larriera see each other almost every day. They blame George W. Bush for the Iraq war, and blame Kofi Annan for sending Vieira de Mello to Iraq. On New Year’s Eve 2006 they drank a bottle of champagne to toast the end of Annan’s term as secretary-general.

The Canal Hotel stands vacant in Baghdad. The building is distinguished by the fading blue and white paint on the arches and the gaping three-story black hole in its side. Under significant pressure from the Bush administration, Annan reestablished a UN presence in Iraq a year after the attack. In July 2004 Ashraf Jehangir Qazi, a Pakistani diplomat, was named special representative. Since the desire to maintain the appearance of independence had long been trumped by security concerns, Qazi lived and worked holed up in the Green Zone, protected now by a small contingent of UN soldiers from Fiji.

32

He and his team offered political and humanitarian advice to the Iraqi government when they could, but their role was marginal. Where once Iraqis who worked for the UN eschewed any connection with the Coalition, today they avoid association with the UN as well, working undercover. In November 2007 Vieira de Mello’s friend Staffan de Mistura replaced Qazi in the thankless job. “I agreed for one reason, for one man,” de Mistura says. “I don’t know anybody who can walk in the shadow of Sergio. But maybe we can all surprise ourselves and achieve something by trying.”

Most of the survivors of the attack and the family members of the deceased went several years without learning the identity of the perpetrators. Only in 2006 did some happen to learn from the media that in January 2005 one Awraz Abd Al Aziz Mahmoud Sa’eed, known as al-Kurdi, had confessed to helping plan the attack for Abu Mussab al-Zarqawi, al-Qaeda’s leader in Iraq. In July 2006 a small UN delegation made its way from Baghdad’s Green Zone to the U.S. detention facility at Camp Cropper, where al-Kurdi was detained. He had been arrested for involvement in another attack and then confessed to his role in the UN bombing.

In a three-hour interview the UN officials were persuaded that al-Kurdi, thirty-four years old at the time of the attack, was not lying. The father of two, he had been imprisoned for joining the rebellion against Saddam Hussein after the Gulf War in 1991. He had been released in 1995 in one of Saddam’s amnesties. He had joined al-Zarqawi’s group in 2002 and served as a driver to al-Zarqawi, who had also lived at his home for four months. Later promoted to become “General Prince for Martyrs,” al-Kurdi said that in August 2003 al-Zarqawi had instructed him to plan attacks on both the Jordanian embassy and the UN headquarters in Baghdad. At that time al-Zarqawi’s network was so poorly understood by U.S. intelligence operatives that he and al-Kurdi had no trouble meeting daily. Later, for security reasons, their meetings would have to be scaled back to once a month.

Al-Kurdi had personally surveyed the premises in advance of the bomb. He had tried several times to enter the UN complex, using a false ID and posing as a UN job seeker, but he had been blocked. He had gotten inside the neighboring spinal hospital with a false identification and surveyed the short distance between the unfinished brick wall and the Canal building. He said that he told al-Zarqawi that there was “only one place where we can get through.” It was via the narrow access road that ran beneath Vieira de Mello’s office.

Al-Kurdi did not personally know that the UN envoy kept his office in the most vulnerable part of the building, above the unfinished wall, but he knew that the UN boss was the target. He had placed the odds of success at only 50 percent “because the truck, going toward the building, could be noticed and even one bullet could have killed the driver.” He said his group had moral concerns. “We realized that this could of course cause damages to the hospital itself and this would damage the reputation of our organization and would backfire on us,” al-Kurdi said. “We were even hesitant to do it.”

On August 18, at al-Kurdi’s house in Ramadi, al-Zarqawi had explained to the designated bomber, Abu Farid al-Massri, the reasons for targeting the UN. Al-Zarqawi told him that al-Qaeda’s decision-making council had ordered the strike because a UN senior official was housed there who, in al-Kurdi’s words, was “the person behind the separation of East Timor from Indonesia and who was also the reason for the division of Bosnia and Herzegovina.” Al-Zarqawi spent the entire night with the bomber, while al-Kurdi and his children slept in the next room. Al-Zarqawi personally helped load the bomb onto the truck. Disappointed by the force of the Jordanian attack, he had been the one to decide to attach mortars and the plastic explosive C4 to the TNT.

Originally al-Kurdi was scheduled to leave Ramadi at 6 a.m. for a 9 a.m. attack, but he received a telephone call before departing, delaying the strike until the afternoon. He drove the truck to the neighborhood of the Canal Hotel and arrived around noon. The bomber was driven separately and met up with al-Kurdi at the Canal at 3:30 p.m. Al-Massri had chosen to set off the detonation device manually instead of having it detonated remotely. Al-Kurdi reminded him of how to use it and pointed out the access road and the target.

After parting ways with al-Massri, al-Kurdi waited across the street for ten minutes, and then, after seeing the truck explode, he melted into the crowd and returned to his home in Ramadi. He had been instructed not to leave the area until he heard the sound of the explosion. When he arrived at his house, however, his coconspirators were angry with him for not staying long enough to be able to report the results. But they later learned from the media that Vieira de Mello had in fact been killed. The UN questioners asked al-Kurdi if he and al-Zarqawi considered the operation a success.“The purpose of the attack was to send the message and [it was] not like a military operation that is a victorious or failing operation,” he said. “But with the death of Sergio, we believed that the message has been fully sent and if Sergio had not died then half of the message would have been sent.”

33

When al-Kurdi elaborated on the motives behind the attack, he said that he had his own view as to why the UN in general and Vieira de Mello in particular were appropriate targets:

For me personally as an Iraqi, I believe that the resolutions of the UN were not just and a lot of harm has been caused to the Iraqi people for thirteen years, like hunger and diseases. Actually, the [UN] sanctions were on the Iraqi people and not on the government . . . Secondly, a lot of Islamic countries have been through injustices and various occupations and foreign troops using the UN resolutions . . . against Muslim people under the name of the UN. Maybe the UN is not the one issuing these resolutions, but there are super powers using the UN. Crimes are committed in Islamic countries and so we wanted to send the message to this organization . . . The compromise can be before the fight, but not after the fight, and if the UN wanted to rescue the people, it should have intervened before the catastrophe [took] place . . . A lot of families and children have been killed.

Al-Kurdi pleaded not guilty in the Iraqi court. He explained his reasoning: “Maybe during some of the operations innocent civilians were killed, but we didn’t intend or mean to kill any child, and if it happened by mistake we asked God for mercy and forgiveness.” The insurgency was fully justified, he said:

My country is occupied, and I didn’t go [to] any other country to fight ... My country has been occupied by foreign troops without any international legitimacy, and the people have been killed, and my religion says that I should fight. Even the Christians and the Seculars say that when your country is occupied you have to fight the occupier, and that’s not only in the Muslim countries but also in the Christian areas like Vietnam, Somalia, and Haiti. Where the countries are occupied, it is legitimate to resist the occupier. There is no religion or international norms or traditions whether Eastern or Western or anybody who is supporting the occupation of my country from either a religious or an intellectual point of view. The ones who cooperate with the occupier should receive the same treatment that the occupier receives . . . As far as I’m concerned, I’m innocent. I didn’t kill any people from the street. I didn’t steal money from any house . . . There are thousands of Iraqis who are in Abu Ghraib jail or other jails of the occupation without charge for two or three years and nobody can help, and you are telling me that you don’t want them to attack the UN or the Red Cross or others . . . When the Americans came, they stepped on our heads with their shoes so what do you expect us to do? Death is more honorable than life . . . You can ask the regular people about this, and now even the people they are wishing that the days of Saddam would come back.

34

On July 3, 2007, as U.S. troops in Iraq prepared to take time away from the bloody civil war in order to mark American Independence Day, the Iraqi government hanged al-Kurdi. In the few wire stories that covered his execution, journalists referred to several of the high-profile attacks he had helped to orchestrate. None saw fit to mention his involvement in the attack on the United Nations.