CHAPTER FOUR

PEKING MAN: A CURIOUS CASE OF PALEO-NOIR

In 2011, Dr. Per Ahlberg, Dr. Martin Kundrát, and curator Dr. Jan Ove Ebbestad began unpacking and cataloging the contents of forty boxes from fossil collections archived in the Museum of Evolution in Uppsala, Sweden. These boxes had not been opened since their materials had been packed off to Sweden from excavations at the well-known archaeological site of Zhoukoudian in China during the 1920s and 1930s. Among crates of the site’s fossil fauna, the Swedish researchers found a hominin canine tooth. The tooth was chipped, the surface was very worn, and the dark brown root had broken off just below the gum line—but it was a tooth that looked surprisingly humanlike.

The Swedish scientists sent the tooth to their colleagues Liu Wu and Tong Haowen, paleontologists at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing, for analysis. Wu and Haowen determined that the tooth was a canine that would have belonged to Peking Man—a series of fossils excavated from Zhoukoudian in the first half of the twentieth century. Today Peking Man is taxonomically assigned to Homo erectus—an extinct Pleistocene species in humans’ evolutionary tree roughly 750,000 years old. But Wu and Haowen’s description also meant that the tooth carried a certain historical distinction. Peking Man—as the assemblage of skulls, jaws, teeth, and other bones was collectively known—was one of the most celebrated fossils discovered at the beginning of the twentieth century. By identifying the tooth as part of Peking Man, the fossil tooth became a lost relic found.1

Recovered canine from Peking Man assemblage, Museum of Evolution, Uppsala University Archives, 2011. (Museum of Evolution, Uppsala University, Sweden. Used with permission)

—

It’s hard to build a coherent narrative based strictly on disjointed details, and Peking Man’s story is full of them: its fossils are a story built out of many stories, without a clear beginning, with many middles, and with no clear ending. Where other specimens like the Old Man or the Taung Child have a very specific moment of discovery and lives as scientific and cultural personae, Peking Man has only its many stories that are told and retold, forming a mythos of importance along nationalistic, scientific, and historical lines.

In the first decade of the twentieth century, paleoanthropology had very few fossils in its collections, and no fossils from mainland Asia. (The only Asian fossil in the historical record at that point was Eugène Dubois’s discovery of Java Man, Pithecanthropus erectus, found on the Indonesian island of Java in 1891—Homo erectus to us today.) By the 1920s, the study of fossils and human evolution in China came from a variety of parties—China’s budding interests in geology and anthropology, as well as investments from outside researchers interested in the artifacts and fossils that comprised China’s archaeological and paleoanthropological records.

On the surface, Peking Man’s story seems rather straightforward. In the summer of 1921, a young Austrian paleontologist, Otto Zdansky, found the first fossil hominin molar later classified as Peking Man while he surveyed the Zhoukoudian caves just forty kilometers outside of Beijing (then romanized as Peking). He picked up the molar and put it in his pocket. The fossil was eventually analyzed, along with other archaeological materials, and all skeletal materials were published in 1927’s Palaeontologica Sinica as part of the new species Sinanthropus pekinensis, or Peking Man. On October 16, 1927, another Sinanthropus tooth was uncovered in the excavations, and Canadian paleoanthropologist Dr. Davidson Black felt confident that these fossils represented a completely new species of human ancestor. Over the course of a decade and a half, other Sinanthropus fossils like skulls, mandibles, teeth, and bone fragments were recovered from Zhoukoudian, enough fossils to represent a population of forty Sinanthropus individuals. Replica casts and museum displays were created, and national narratives written. Then, in December 1941, the fossils were lost during an attempt to ship them out of China before the invasion of the Japanese army. After the fossils went missing, they maintained their cachet through their casts and photographs. But the mystery of their disappearance and the question of where those original fossils went intrigued the scientific community and captured popular imagination, to say nothing of the interest of the government of China. All attempts to locate the fossils have ended in failure.

The Peking Man’s story is, of course, much more complicated and much more interesting. When Dr. Johan Gunnar Andersson, director of Sweden’s Geological Survey, came to China in 1914, he had been hired as a mining adviser to the Chinese government. Andersson was a self-described “mining specialist, a fossil collector and an archaeologist” who had led a Swedish survey in Antarctica from 1901 to 1903.2 His arrival and interest in fossils, however, helped initiate a series of surveys and new modern research methodologies in northern China together with his Chinese and Swedish colleagues. The growing interest in Chinese history, prehistory, and paleohistory put China on a clear trajectory to becoming a major scientific force in archaeology and geology by the mid-twentieth century. “To many anthropologists in the 1920s, Asia seemed the most likely place for ‘the cradle of mankind,’” offers historian Dr. Peter Kjaergaard. “Fame, prestige and money were intimately connected in the hunt for humankind’s earliest ancestors and, thus, a lot was at stake for those involved. Several countries were competing for access to China as ‘the paleontological Garden of Eden.’”3

Andersson’s interest in China’s fossils had been piqued by German paleontologist Max Schlosser’s “dragon bone” findings from Schlosser’s own travels in China over a decade earlier; by the time Andersson arrived in China, Schlosser’s fossils had been taxonomically identified to ninety species of mammals. Many of the early fossil collectors came to find their specimens through Chinese locals who hunted the “dragon bones”—as fossils were called—as components for traditional medicines. Archaeologists went to dragon bone hunters for leads, suggestions, and the fossils the apothecaries had collected. In Schlosser’s fossil collection was a humanlike third upper molar that piqued Andersson’s interest in the area as a viable site for investigating human origins in Asia. For Andersson, this lone rogue tooth meant that there was clear evidence of early man in China; he just had to find it. From 1914 to 1918, Andersson paid a number of local technicians (or assistants, as he called them) for fossil hunting in the Shanxi, Henan, and Gansu provinces with the hope that some of these locales would successfully yield “dragon bones” or some other interesting objects of antiquity. Any materials that Andersson’s lackeys recovered were promptly sent to Professor Carl Wiman of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology at Uppsala for study. In late autumn of 1920, Andersson’s assistant Liu Chang-shan returned to Beijing with several hundred stone axes, knives, and other stone artifacts, all of which were from a single spot in the village of Yangshao in Henan.

Particularly significant about Andersson’s work was his reliance on geological methods for excavating and his commitment to scientific methodology. “With geology, and the principles of stratigraphy as a means of exploring the dimension of time, there simply could be no scientific archaeology or any of its excavations that characteristically focus on the delineation of the context of objects,” notes historian Dr. Magnus Fikesjö. “Andersson arrived . . . [at] his famous position at the beginnings of Chinese archaeology by way of his geology, precisely by observing stratigraphic patterns and scanning the landscape for traces of paleontological and human remains that might constitute new discoveries.”4 Artifacts were mapped to specific strata, and sites could be interpreted as a sequence of events with each of the excavated objects offering clues about what those events could have been. The reliance on geology’s scientific framework firmly established the initial excavations—and the later excavations at Zhoukoudian—as credible modern science in China.

By 1918, Andersson’s interest in fossils resonated with his colleagues, and J. McGregor Gibb—who was teaching chemistry in Beijing—showed Andersson some red-clay-covered fossil fragments from a place called Jigushan (“Dragon Bone Hill”) near Zhoukoudian. (Zhoukoudian—also known as Chou Kou Tien or Choukoutien—was about forty kilometers from Beijing.) Andersson set out by mule on March 22, 1918, to explore the Zhoukoudian area, a day’s travel from his home in Beijing. There, Andersson found a series of extensive limestone caves, with thick, fault-crossed sedimentary bands. Legend—coupled with oral history—has it that the Zhoukoudian area was first recognized as a fossiliferous locale as early as the Song dynasty (960–1279 CE), when archaeological evidence of limekilns appear in the area. Over millennia, the groundwater erosion of the limestone created caves and fissures, classic geomorphic catchment areas for the fabled dragon bones.

Andersson’s initial exploration of the area reinforced his notion that it would be ideal for more systematic work, and in 1921 he assigned a young Austrian paleontologist, Otto Zdansky, to survey parts of the area. Zdansky, a recent graduate from the University of Vienna, had joined the team to collect fossils for Uppsala University. “I have a feeling that there lie here the remains of one of our ancestors and it is only a question of your finding him,” Andersson gushed to Zdansky upon the latter’s arrival at Zhoukoudian. “Take your time and stick to it till the cave is emptied, if need be.”5 Since Zdansky did not receive a salary for his work (although his expenses were covered), he had negotiated the rights to describe any fossil discoveries he made in the course of his work at Zhoukoudian. While Zdansky somewhat reluctantly began excavations at Zhoukoudian, Andersson turned his own attention to generating interest in the sites from other scientific institutions, organizing grants and donations and raising awareness about the site’s significance. In one effort, Andersson brought Walter Granger, the chief paleontologist for an expedition underwritten by the American Museum of Natural History, to search for “early man.” The plan was to garner Granger’s notice about China’s value to prehistory and the contributions China could offer the still developing scientific field, thus putting China’s fossils squarely at the forefront of paleoanthropology’s burgeoning interest in Asia.

During the 1921 field season, Zdansky unearthed that single tooth—a tooth with a worn-down crown and three roots. “Although Zdansky did not acknowledge the stone tools at Zhoukoudian as such,” Kjaergaard argues, “[h]e soon realized that there was indeed ancient human remains buried at Choukoutien. However, he kept it to himself and put away the tooth he found. According to his own explanation, he did not want to let the sensation of a potential human ancestor cloud more important work. But, of course, he was perfectly aware of what this could mean for his career and what a compensation it would be for working without a proper salary.”6

Zdansky did, however, deign to produce the tooth for visitors during the visit of the crown prince of Sweden to the site in 1926. But it wasn’t until 1927 that the molar, in addition to another tooth fragment recovered from the excavation materials in the crates, was published by those working at the site. The tooth was identified as a molar from the right side of the mouth, from a species that Zdansky tentatively assigned to the genus Homo. (He put a question mark next to the species name.) Although Zdansky published his Zhoukoudian experiences in 1923—including a fossil catalog list of all the species recovered and identified—the questionable Homo tooth was conspicuously absent. After a subsequent field season in 1923, Zdansky returned to Uppsala and simply analyzed the tooth with the specimens recovered from his excavations. Although he bowed out of subsequent research at Zhoukoudian, the publication of a hominin tooth marked the beginning of a dedicated search for human ancestors at the site.

—

The presence of an “early man” or that elusive hominin ancestor—even if that presence was marked by just two teeth—was enough to motivate international agencies, like the Rockefeller Foundation, to fund excavations at Zhoukoudian. By 1927, the Rockefeller Foundation funds had arrived and systematic excavations began in earnest, under the leadership of Chinese scientists Dr. Ding Wenjiang (as the project’s honorary director) and Dr. Weng Wenhao (later director of China’s Geological Survey), as well as Canadian paleoanthropologist Dr. Davidson Black. Four scientific specialists—Dr. Anders Birger Bohlin (accompanied by his wife), Drs. Li Jie, Liu Delin, and Xie Renfu—were in charge of excavations and laboratory work. Other workers were hired, including a field manager and cook. Members of the field team stayed at the Liu Zhen Inn, a camel caravan inn that had just nine tiny damp adobe rooms. Located a mere two hundred meters from the site, it was rented by Li Jie for fourteen yuan a month and functioned as an ideal field headquarters between 1927 and 1931. Initial fieldwork began on March 27, 1927. Researchers conducted a systematic survey of the entire Zhoukoudian complex, extending to the county seat of Fangshan, where earlier maps had been limited to only the Peking Man site proper. Full-scale excavations then began on April 16, 1927.

In addition to excavation funds, the Rockefeller Foundation sponsored the building and management of the Cenozoic Research Laboratory. Founded in 1928 by Davidson Black, Ding Wenjiang, and Weng Wenhao, the laboratory was a part of the Peking Union Medical College with the help of an $80,000 grant that Black had received from Rockefeller. The laboratory was specifically tasked to oversee the Peking Man material as the sheer amount of materials excavated and blasted out of the Zhoukoudian site boggles the mind: fossil specimens from the 1927 field season filled a staggering five hundred crates. Most of this fossil material was later shipped to the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities in Sweden. (The transportation of the fossils from Beijing to Sweden wasn’t without its own dangers; in November 1919, the Swedish ship Peking sank in a storm with eighty-two crates of plant and animal fossils on their way to Sweden for analysis. The loss of these fossils was a huge blow to the early days of Andersson’s research.)7

By October 16, 1927, three days before the field season was supposed to end and as the team was beginning to wrap up their excavations, an in situ hominin tooth was discovered close to where Zdansky had found that tooth years earlier. In a letter dated October 29, 1927, Davidson Black wrote to Andersson, who was in Stockholm at the time:

We have got a beautiful human tooth at last!

It is truly glorious news, is it not!

Bohlin is a splendid and enthusiastic worker who refused to permit local discomforts or military exercises to interfere with his investigation. . . . I couldn’t get away myself for I was having daily committee work that demanded my presence here. Hsieh (Zie Renfu) couldn’t reach Chou Kou Tien on account of local fighting. That night which was October 19th when I got back to my office at 6:30 from my meeting there I found Bohlin in his field clothes and covered with dust but his face just shining with happiness. He had finished the season’s work in spite of the war and on October 16th he had found the tooth; being right on the spot when it was picked out of the matrix! My word, I was excited and elated! Bohlin came here before he had even let his wife know he was in Peking—he certainly is a man after my own heart and I hope you will tell Dr. Wiman how much I appreciate his help in securing Bohlin for the work in China.

We have now in Peking some 50 boxes of material which we got in last July when the last military crisis was on but there are 300 more large boxes yet to come from Chou Kou Tien. Mr. Li of the Survey is busy trying to get rail cars to bring back this material. It will fill more than two cars!8

His enthusiasm was well placed. Before 1929, the excavations at Zhoukoudian had resulted in only a few more isolated hominin teeth—not a lot more than what had been recovered between 1921 and 1927. The 1929 field season saw the beginning of excavations in the middle part of the Zhoukoudian deposits—these deposits were west of the northern fissure that crossed the site. The 1929 field season proved to be a real turning point in the Zhoukoudian excavations, in large part due to what was uncovered in December of that year. “Dragon Bone Hill”—also referred to as “Locality 53” in Andersson’s early notes—was renamed “Cave 1” and appeared as such in all subsequent documentation. The project paid a yearly rent of 90 yuan to a coal company (the hill was a quarry site the company owned), which was raised to 180 yuan after 1927. To prevent what excavators considered “extortion,” the Cenozoic Research Laboratory paid the “exorbitant” price of 4,900 yuan for permanent use of the site.

Where Bohlin and Li Jie had shared administrative and scientific affairs, paleontologist-anthropologist Professor Pei Wenzhong had to deal with the overwhelming logistics of running such a large site by himself; in interviews decades later, Pei recalled that he was seized by melancholy after Black left in April 1929 and Pei took over the site’s care.

By November 1929, the site proved to be extremely rich in fauna—145 antelope jaws were excavated in one day, for instance. The cache of antelope joined the faunal record with complete pig and buffalo skulls, as well as antlers—yet few hominin teeth. In the late afternoon of December 2, 1929, however, the story of human origins in China found itself with a new fossil character. Workers discovered a skullcap in the fifth stratigraphic layer at Zhoukoudian; the presence of the cranium was clear, irrefutable evidence that the story of human evolution had early ties to China. The discovery of these fossils meant that China’s rather recent use of geologic methodology and science was able to juxtapose itself with a strong commitment to “Chinese” historical antiquity, giving the entire excavation a nationalist agenda. With this one discovery, Chinese history pushed its antiquity and “legitimacy” back to the Pleistocene and became a serious force within the developing science of human origins.

Archaeologists and workers excavating at the Peking Man discovery site, China, 1920s. (Science Source)

The sheer excitement of the discovery was unmistakable. In a series of interviews in 1980, Pei Wenzhong recalled the details from December 2, 1929:

In the afternoon after four o’clock, it was near sunset and the winter wind brought freezing temperatures to the site. Everybody felt the cold, but all were working hard at finding more fossils. . . . The large number of fossils attracted everyone of us and we all went down to take a look, so I know what it was like down there in the crack.

We generally used gas light, for it was brighter. But the pit was so small that anyone working there had to hold a candle in one hand and work with the other.9

—

Prehistorian and archaeologist Dr. Jia Lanpo offered his recollections of the discovery of the first Peking Man skull:

Maybe because of the cold weather, or the hour of the day, the stillness of the air was punctuated only by occasional rhythmic hammer sounds that indicated the presence of men down in the pit. “What’s that?” Pei suddenly cried out. “A human skull!” In the tranquility, everybody heard him.

Pei had gone down after the sighting of the fossils, and now, where he was told there was a round-shaped object there, he had stayed there and worked with the technicians. As more of the object became exposed, he had cried out. Everybody around him was excited and gratified at the long-awaited find.

Some suggested that they take it out at once, while others objected for fear that, working rashly in the late hours, they might damage the object. “It has been there for so many thousands of years, what harm would it do lying there for one more night?” they argued. But a long night of suspense was too much to bear.10

Pei’s terse telegraph to Black fittingly captures the emotion of the moment: “Found skullcap—perfect—look[s] like man’s.”11 The news was scarcely believed at first; skeptics either doubted Pei’s ability to correctly identify the fossil specimen or, after two years of excavations with only the occasional tooth to show for their efforts, refused to believe that the excavations could have been so lucky. In a letter to Andersson dated December 5, 1929, Davidson Black wrote: “I had a telegram from Pei from Chou Kou Tien yesterday saying he would be in Peking tomorrow bringing with him what he thinks is a complete Sinanthropus skull! I hope it turns out to be true.”12

Simply finding the fossil wasn’t enough, though. The specimen had to be carefully excavated and transported to the Cenozoic Research Laboratory. Excavating and storing the fossil was a bit tricky; when that Sinanthropus fossil was first unearthed, the specimen was rather wet and soft, due to the cave’s sediments, and could be damaged easily. The specimen thus had to be dried out before it could be transported to Beijing. Pei and fellow archaeologists Qiao and Wang Cunyi stayed day and night next to a fire to dry out the skull. Pei carefully wrapped it in layers of gauze; the gauze was covered with plaster and dried again; then it was all wrapped in two thick cotton quilts and two blankets and the entire specimen was then trussed up with rope. What had been so carefully excavated from one set of soil and cave sediments was now jacketed in a new stratigraphy of cultural layers and materials. Pei delivered the first complete skull of the Peking Man assemblage to Davidson Black at the Cenozoic Research Laboratory on December 6, 1929.

Excavations at Zhoukoudian showing how fossils were jacketed in situ for safe removal. From Paramount News film, early 1930s. (Film courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History Library and Dr. Milford Wolpoff)

China’s Geological Survey held a special meeting on December 28, 1929, to announce the discovery; the next day the foreign press reported the news of the phenomenal fossil find, which quickly spread across global scientific communities. Scientists like British anatomist Grafton Elliot Smith—while still immersed in sorting out the anatomy of Piltdown Man—visited Beijing in September 1930 to examine the Peking Man fossils. Over the next few years, the Cenozoic Research Laboratory continued its excavations at the Zhoukoudian sites, and additional fragments of skulls, jaws, and teeth were recovered; all were assigned to Sinanthropus.13

On March 16, 1934, Davidson Black passed away—he was found dead that morning with the Zhoukoudian specimens lying in front of him as he attempted to catch up with work. Dr. Franz Weidenreich, a German anatomist, took over Black’s position and work in 1935. Weidenreich’s attention to detail and scientific brilliance helped push the scientific import of the Zhoukoudian fossils to the forefront of the scientific community. Unfortunately, Weidenreich was not as sociable and personable as his predecessor. He left all administrative organization and affairs to his Chinese counterpart in the laboratory, Yang Zhongjian, who had earlier directed the excavations at Zhoukoudian, from 1928 to 1933. As a result of Weidenreich’s reticence about administrative affairs, the Rockefeller Foundation stopped supporting the Cenozoic Research Laboratory directly, although the Foundation continued to finance the Zhoukoudian excavations, allocating money for continued work there through March 31, 1937. In meeting minutes, the Rockefeller Foundation acknowledged the incredible scientific significance that the site offered both China and the international community:

The paleontological finds in the caves of Choukoutien near Peking constitute one of the most dramatically interesting and significant advances ever made in our knowledge of ancient man. The scientific importance of this work can not be questioned, and the collapse of the program would be a major scientific loss. The program has, moreover, been closely associated from the outset with the Peiping Union Medical College. It represents a fine-spirited cooperation between Chinese and western scholars and in terms of scientific competence and achievement it is outstanding in China’s experience. It was natural to fear that Dr. Black’s death would mean the virtual end of this project. However, Dr. Franz Weidenreich, formerly of the University of Frankfurt and of the University of Chicago, has, since his appointment in March, 1935, demonstrated the necessary qualities of scholarship, administrative ability, tact, etc., to carry forward with distinguished success the work which was so brilliantly begun by Dr. Black.14

Despite this endorsement, the beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937 and the difficulties that the war raised meant that excavations at Zhoukoudian stopped and fossils were carefully locked away in the laboratory. Weidenreich was concerned that if Japan and the United States went to war, the Japanese would take over the lab; in the summer of 1941, Weidenreich insisted that additional replicas of the bones be created. In late 1941, Weidenreich left Beijing, opting to take a position at the American Museum of Natural History.

—

So what made Peking Man “Peking Man”? Taxonomically, Peking Man was part of a species that Johan Andersson and colleagues named Sinanthropus pekinensis—not a single individual but a series of individuals now known as Homo erectus. Davidson Black’s initial morphological studies described a species similar to modern humans, having a large brain but overall similar skull and bone sizes. Sinanthropus, however, was different in that it had heavy brows and large, chinless jaws. Geologically, the site dates to between 750,000 and 530,000 years ago. Today, thanks to extensive analyses of the site’s artifacts, we know that the species had sophisticated stone tools and offered the first systematic use of controlled fire outside of our own species, Homo sapiens. From a historical standpoint, however, the moniker “Peking Man” refers to the assemblage of fossils found at Zhoukoudian. When we talk about “Peking Man,” we are thus implicitly referring to both a taxonomic moment in time and the identity of a historical object.

“There is a celebrity around the fossils, especially in the 1920s and 1930s, when they become quite individualized and personalized,” historian Dr. Christopher Manias explains. “You do get the sense that the media or popular accounts are talking about ‘Peking Man’ as a definite individual and trying to work out what ‘he’ was like: who he was, when he lived, what moral standard he was at, what he ate, how much like ‘us’ he was, and so on.”15

Where other fossil discoveries had clear nationalistic ties—the Piltdown Man, for example, was touted as “the earliest Englishman”—no other discovery was quite as inexorably linked to the development of science writ large in the way that Peking Man was. Many standard histories regard the development of modern geology in China as influenced by foreign imperialism, with only a few Chinese students studying abroad in the West and then returning to China in the early to mid-twentieth century, bringing back with them Western techniques and theories. This was different than science done in British colonies, and to that end China had a different kind of paleoanthropology than the science that surrounded the Taung Child in South Africa. One of the reasons that the European paleointelligentsia was so sniffy about Taung’s discovery was that the fossil and the fossil’s ancestral interpretation had come from a colony—South Africa—and they felt it ought to have been validated by the European (specifically British) establishment.

The introduction of the scientific methodology and framework offered a means of legitimizing China’s presence and participation in global scientific norms of geology. “To China’s geological pioneers, the connection between nation and science was even more basic. Whether they were collecting rocks and fossils or elucidating earth processes, they were in a sense studying China directly and fitting it into a global narrative,” argues historian Dr. Grace Yen Shen.16 Participating in these new frameworks of geology and archaeology became a way for China to take part in the global modernity of geological sciences, and China was now a serious player in paleoanthropology. It’s hard, in fact, to imagine a more global perspective than a search for “early man”—which was, after all, how the Zhoukoudian project unfolded. It was backed by a variety of international participants, and the site and its treasures meant that Sinathropus’s early identity was an international one. Workers at the site were Canadian, Swedish, Austrian, German, and French as well as Chinese. Moreover, the excavation of Zhoukoudian tapped into a variety of scientific, intellectual networks devoted to studying archaeology, human evolution, and the longue durée of human history, with international ties due to the long-running Swedish connection, as well as a French involvement.17 Even with this international focus, the fossils themselves became a strong symbol of China and its history.

—

While the specific moment of the discovery of the Zhoukoudian fossils is a bit ambiguous, the date of the fossils’ disappearance is specific—but circumstances, even decades later, are far from clear. And as with most aspects of Peking Man, there is a long version and a short version to the story.

In the short version, researchers at the Peking Union Medical College, especially Franz Weidenreich, were concerned about the safety of the fossils due to building tensions between China and Japan between 1939 and 1941. When the United States declared war on Japan on December 8, 1941, after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the Japanese military took over the Peking Union Medical College. Concerned that the fossils would be looted from China—or completely destroyed—the College carefully crated the Peking Man fossils with the intention of smuggling them out of China to the United States or Europe. The fossils were packed into two crates and driven to the U.S. Marines’ base at Camp Holcomb, where they were scheduled to be shipped out on the USS President Harrison. However, the fossils happened to arrive at the base just a few days before the U.S. military base surrendered to the Japanese. Somewhere between the departure of the fossils from Beijing and loading on board the Harrison, the fossils were lost in the confusion and pandemonium.

The long version of the Peking Man disappearance reads like something straight out of a Dashiell Hammett novel—there’s mystery and intrigue, some fact but more fiction. It’s as if the hardboiled detective Sam Spade has been tasked to track down priceless scientific curios.

In preparation for transport, anatomy technicians Ji Yan-qing and Hu Chengzhi of the Cenozoic Research Laboratory wrapped each fossil in white tissue paper, cushioned them with cotton and gauze, then overwrapped the fossils with white sheet paper. The fossils were placed in small wooden boxes with several layers of corrugated cardboard on all sides. The smaller wooden boxes were then placed into two big unpainted wooden crates, one of which was approximately the size of a large office desk and the other slightly smaller. The crates were delivered to Controller T. Bowen’s office at the Peking Union Medical College. Once the Japanese military attacked Pearl Harbor and the Japanese took over the College, the fossils in their crates were moved around different storerooms, then quickly delivered to the U.S. embassy at Dong Jiao Min Xiang in Beijing. All of this occurred three weeks before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The contents of the two crates reflected the vast amount of archaeological materials that had been excavated at the Zhoukoudian site. Case 1, for example, had seven boxes nestled into the desk-sized crate: Box 1 contained teeth (in seventy-nine separate smaller boxes), nine thighbone fragments, two fragmented humeri, three upper jaws, a collarbone, a carpal bone, a nasal bone, a palate, a cervical vertebra, fifteen skull fragments, a separate box of skull fragments, two boxes of toe bones, and thirteen boxes of mandibles. Case 1 also contained six additional boxes of skulls and a small container of orangutan teeth. With the exception of the orangutan teeth, all of the fossils in Case 1 were assigned to Peking Man, indicative of how Peking Man, with thirteen jawbones and nine thighbones, reflected an assemblage of multiple individuals that represented all genders and ages. The second crate contained a similar swath of Peking Man fossil remains, plus several macaque (monkey) skulls. The lab took careful notes about these crates as well, noting who packed which one and what kind of packing materials were used. Although these crates were also lost and never recovered, the notes about their contents have survived.

Backing up, however, to the buildup of political and military tensions in November and early December 1941, Dr. Weng Wenhao, the director of China’s Geological Survey, appealed to Dr. Henry Houghton, president of the College, to have the Peking Man collection taken to safety. Houghton asked Colonel William W. Ashurst—a commander of the marine detachment at the U.S. embassy in Peking—to send the Peking Man collection to safety, under protection of the marines, leaving within a couple of days. At five a.m. on December 5, the marines’ special train—with the Peking Man fossils—pulled out of Peking, headed down the Japanese-owned Manchuria railroad toward the small Chinese coastal town of Chinwangtao. From Chinwangtao, the Peking Man materials were to be loaded onto the American liner USS President Harrison, which was to head to Shanghai, then north from there.

However, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor halted all plans. To prevent the capture of the Harrison, her crew grounded her at the mouth of the Yangtze River, and the marine train with the fossils was captured by the Japanese at Chinwangtao. What happened to the two large crates of Peking Man remains has been the subject of much speculation, due in no small part to the varied and often contradictory testimonies of different witnesses. “What happened from that moment on is clouded in rumour and the confusion of war,” author Ruth Moore writes in her account of the Peking Man disappearance. “Despite the efforts of three governments to find them, they have vanished from the world as completely as during the centuries when they lay hidden in the earth of Dragon Bone Hill. According to one account, the Japanese loaded all the cases taken from the train on a lighter that was to take them to a freighter lying off Tientsin. The lighter, it is said, capsized, and the remains of Peking Man drifted away or sank to the bottom of the sea. The other story is that the Japanese who looted the train knew nothing of the value of the scraps of bone and either threw them away or sold them to Chinese traders as ‘dragon bones.’ If so, they may long since have been ground into medicine.”18

—

Since the Peking Man story lacks a satisfying resolution, many believe that the fossils are still out there just waiting to be rediscovered, and such believers have mounted decades of searches.

This is where, in 1972, one Christopher Janus—a U.S. financier and philanthropist from Chicago—enters the Peking Man story. Janus was no stranger to public outrage, having himself owned and driven Hitler’s limousine. Moreover, in 1950, he’d inherited a cotton plantation and “fifty Egyptian dancing girls,” whom he used as a vaudeville act; the exasperated Egyptian embassy spent months explaining that slavery was outlawed in Egypt and desperately tried to distance themselves from Janus, whom they had come to see as a political leper.

Like a character straight out of a film noir (and with a name to match), Janus was determined to write his own chapter of the Peking Man story. The disappearance of the fossils had attracted his interest during his visit to China in 1972 among the first group of Americans allowed to visit the country as it reopened to the West. His dynamic personality was matched by his penchant for history and interest in culture. Although Janus had no training as an anthropologist—he admitted that he had never even heard of the Peking Man fossils before his trip and his visit to the Peking Man Museum—Janus felt that he had been selected and charged by Dr. Wu of the Peking Man Museum at Zhoukoudian to find the fossils and return them to China. To read how Janus tells his story, the return of the Peking Man fossils turned into a personal mission. Upon his return to the United States, Janus quickly set to finding the missing specimens, offering a $5,000 reward for information about their whereabouts.

His book, The Search for Peking Man, teems with mystery and conspiracy—clandestine meetings, cloak-and-dagger innuendo, and international intrigues. The first couple of chapters of the book describe the loss of the fossils and relate in vivid detail how a Dr. Herman Davis supposedly used the boxes as poker tables. According to Janus’s “research,” Davis even used the crates of fossils to steady his machine gun during the Japanese invasion of the base. Janus has people coming out of the woodwork to offer their take on the possible fate of Peking Man: some claim to know where it is; others claim to actually have the remains. For example, Mr. Andrew Sze, a Chinese expat living in the United States, claimed that the fossils were in Taiwan and his best friend knew the exact location. The climax of Janus’s search involved a particularly furtive meeting with a woman who claimed to have the fossils in her late husband’s U.S. Marine footlocker—he had brought the fossils back from his deployment in World War II, she said. Janus was to meet the woman at the top of the Empire State Building at noon one spring day; she told him that he would know her because she would be wearing sunglasses. On the rooftop, she gave him a blurry photo of what looked like fossils, then utterly vanished. (Harry Shapiro, of the American Museum of Natural History, was dubious at best about the materials when Janus asked him to look at the photo to authenticate the fossils. The photograph in question is spectacularly blurry and conveniently out of focus.) Janus also claimed his search for the fossils continued—rather improbably—with help from the FBI and CIA, claiming to want to help him locate the fossils “in the national interest.”19

Janus’s hunt for Peking Man came to a screeching halt on February 25, 1981, when he was indicted by a federal grand jury on thirty-seven fraud counts. Prosecutors charged that the international search for the bones amounted to a $640,000 fraud in which Janus had funneled the majority of the funds—$520,000 in bank loans and $120,000 from investors to finance the search and produce a film—toward his personal use. In an interview with the Chicago Tribune, Janus insisted that all the money he borrowed was for the search and the planned film. After his indictment, Janus hinted that U.S. relations with China would be ruined if the federal government took action against him. “The whole thing is more than the search for the Peking Man,” Mr. Janus told the press. “It involves certain relationships with China that can’t be discussed, a project we have going with the Federal Government.”20

The grand jury concluded that Mr. Janus had made no serious effort to search for the Peking Man or to make the film. But it could not find out what he did with most of the money he’d borrowed. “He’d say, ‘I see Harrison Ford as me,’” recalls William Brashler, coauthor of The Search for Peking Man, in an interview with the Wall Street Journal. “He immediately hit me up to invest in the movie. It was hard not to like him, but he had one arm around your shoulder and the other in your wallet.”21 Ultimately, Janus pled guilty to two counts of fraud.

Where characters like Janus found blatant means of inserting themselves into the Peking Man story, others, like Claire Taschdjian, a technician at the Peking Union Medical College and one of the last people to have seen the fossils, participated in the Peking legacy in a more subtle way. Taschdjian wrote The Peking Man Is Missing—a fictionalized account of the fossils’ disappearance. (The book can most charitably be described as sensationalistic—full of torpid prose, kept together by a hilariously simplistic plot.) But Taschdjian was a secretary at the laboratory in Beijing when the fossils were lost, and by a quirk of historical happenstance, her comments on the fossils—and anything she writes—have a tell-all sensationalism to them since she was one of the last people to have seen the actual fossils. In January 1975, the original Hawaii Five-0 ran an episode, “Bones of Contention,” in which Steve McGarrett’s team tracks down the “world’s oldest missing persons case”; they find the remains of Peking Man in a military storage unit in Hawaii. It’s the thrill of the hunt, the treasure, and the mystery that drives the fiction. And it’s that very sensationalism that cuts to the core of how we are geared to think about the Peking Man story. The fossils’ fame hinges now on the mystery and intrigue that surround him; it’s only logical, then, that the stories we create and repeat about the fossil end up just as romanticized as the fossils themselves.

Even as recently as July 2006, Beijing’s Fangshan district government announced that it was renewing its search for the fossils. A committee of four from the museum located on the Zhoukoudian site began to gather leads for the fossils’ whereabouts throughout China. A search hotline was even published in the local newspapers; by the fall of that year, the committee announced that sixty-three total leads had come in. One committee member, quoted in multiple newspapers, said that four leads looked “especially promising.” Lead number one: A “121-year-old man” who had served as a high official in Sun Yat-sen’s republican government said he knew exactly where the fossils were. Lead number two: An “old professor” from northwest Gansu Province, during a visit to Japan, had found revealing testimony from an American soldier in the Tokyo military tribunals’ archives. Lead number three: A Mr. Liu, from Beijing, said he knew an “old revolutionary” who had a skull in his possession. Lead number four: Another Beijing man said that his father, a former doctor at Peking Union Hospital, had brought one of the skulls home from work one day and buried the fossils in his neighbor’s yard.22

None of these leads panned out.

—

If the fossils are missing, how can Peking Man have any kind of scientific legacy? In the first part of the twentieth century, casts of fossil specimens were the key to paleosciences. Since fossils were too valuable and rare to ship to international researchers, casts of fossils were sent through networks of natural history institutions. (Recall that Raymond Dart had specifically insured the Taung Child for marine travel when he sailed to London from South Africa.) In the early days of human origins research, paleoanthropologists would offer to trade casts of “their” fossil to other researchers in different areas of the world who had different specimens—the casts thus became a kind of social currency. Scientific colleagues—both collaborators and detractors—wanted to see copies of the fossil in order to examine its anatomy for themselves. People outside of academic circles had heard of the famous fossils and expected to see them in public museums. In order to circulate them for study and display, accurate copies of the fossils had to be made.23

Casts of Peking Man skull at the Cenozoic Research Laboratory, curing and drying on laboratory bench. From Paramount News film, early 1930s. (Film courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History Library and Dr. Milford Wolpoff)

“All [Sinanthropus pekinensis] casts are made and coloured with extreme care and attention to the finest detail. They can be studied with complete confidence,” advertised the catalog for R. F. Damon & Co., purveyor of fossils and creator of fossil casts.24 With the company’s new catalog page for the fossils excavated during Zhoukoudian’s field seasons of the early 1930s, access to Peking Man was suddenly available to international researchers. Every scientist from Sir Arthur Keith in London to Raymond Dart in South Africa could examine the remarkable Zhoukoudian finds.

To that end, on August 2, 1930, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin wrote to Marcellin Boule about the exciting discoveries at Zhoukoudian and Teilhard de Chardin’s own studies in working out the comparisons between different fossil taxa. A powerful presence in the early-twentieth-century paleo world (having worked with both the La Chapelle Neanderthal as well as the Piltdown fossil), Teilhard de Chardin shifted the focus of his work to China when excavations began at Zhoukoudian. “On returning to Peking, I had the pleasant surprise of finding at Black’s laboratory a second skull of Sinanthropus, identical to the first by form and also (fortunately) by its state of conservation. In this second sample, one discerns the beginning of the nasal bones, and some further details,” Teilhard wrote. “Black has made some casts (very good ones) of all the isolated pieces. Two weeks from now, he should be able to give an estimate of the cranial capacity, taken from one absolutely perfect piece as preparation.”25

Although they made the exchange of scientific information easier, the casts represented a huge commitment of time, resources, and investment. “Casts preserve the external form of the fossil, and they thus represent a permanent duplicate record of the shape of fossil bones. They are routinely used in place of original fossils for research, since they enable scientists to study and compare the remains of animals that have been discovered thousands of miles apart, and may be stored on different continents,” museum curators Drs. Janet Monge and Alan Mann explain. “Virtually every paleontological museum and academic department spends considerable time in the procurement of quality casts for both research and instructional purposes.”26

By 1932, when R. F. Damon & Co. was expanding its collection of Sinanthropus casts, Robert Ferris Damon inherited the company from his father, Robert Damon. Damon Senior had established himself in the fossil business in 1850, undertaking the artistic and technological aspects of creating good fossil casts for paleontologists and prehistorians. All of these casts were made of heavy plaster and were used by museums in collections as well as in displays. In the early days of the casting company, between 1850 and 1900, most of the casts and models were marine shells and fish. With the influx of hominin fossils, the company expanded its paleontological collections to include anthropological casts and models. As interest burgeoned in obtaining casts of human ancestors and anthropological specimens, the company focused on skulls, jaws, and teeth of humans and their ancestors. With the discovery of fossil hominins in Southeast Asia in 1891 (Java Man), Europe in 1912 (Piltdown), and Africa in 1924 (Taung Child), many researchers and museums wanted access to copies of fossils to be able to examine the specimens for themselves.

In the mid-1930s, R. F. Damon & Co. was authorized by Davidson Black and Weng Wenhao to expand the list of casts available of Sinanthropus pekinensis as more and more specimens of Peking Man came from the excavations. These new casts included eight mandibular fragments from a variety of differently aged individuals, juvenile through adult, to a skull from Locus E and based on the materials from Davidson Black’s 1931 publication in Palaeontologia Sinica. Prices for such materials were usually several pounds.

Without any originals whatsoever, researchers are left with only the casts as the material evidence and tangible remains of the early Zhoukoudian excavations. Where other casts merely carry the information of the original fossils, the Peking Man casts have come to take the place of the originals. “Fortunately, during the time when they were studied in China, quality plaster casts of almost all of the Zhoukoudian bones were made and distributed to major museums around the world,” Monge and Mann note. “These casts preserve a remarkable amount of detail, and in many cases, measurements taken from them show no significant difference from measurements recorded on the original fossils. This represents a remarkable achievement considering the level of molding and casting technology in the 1930s, and the (by today’s standards) primitive molding media. Although no cast is an ideal substitute for the original fossil, in this case, the casts represent the only record of these specimens, and provide a reasonable alternative for the missing originals.”27

Brochure advertising Peking Man casts from the prominent R. F. Damon & Co. (Raymond Dart Collection. Courtesy of the University of the Witwatersrand Archive)

In 1951–1952, when China was actively looking to have the original Peking Man fossils returned, the casts were confused with the original specimens. In a letter dated October 6, 1951, Dr. Walter Kühne, a paleontologist at Humboldt University in Berlin wrote to Yang Zhongjian, the director of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing. In his letter, Kühne claimed to have been told by a colleague, Dr. D. M. S. Walson, that Walson had seen skullcap 2 of Zhoukoudian at the American Museum of Natural History in New York and, further, that Walson had seen Weidenreich himself handling the specimen. This claim about the fossils immediately sparked an editorial in the People’s Daily (dated January 1, 1952) that urged the American Museum of Natural History—and, indeed, the United States—to return the fossils to the People’s Republic of China. However, in a letter dated April 29, 1952, Dr. Joseph Needham, president of the Britain-China Friendship Association, proved that Walson was mistaken about the identity of the fossil and included a letter from Dr. Kenneth Oakley (of Piltdown debunking fame) that demonstrated that what Walson had seen was, in fact, merely casts. Walson himself retracted his claim once his error had been pointed out.28

What does it mean, then, for us to be left with the replica of a fossil? Does it even matter? “Even without the originals, the duplicates of the Peking Man fossils made before their disappearance have provided substantial information for morphological studies of Homo erectus,” historian of science Dr. Hsiao-pei Yen claims. “Therefore, it is questionable if the discovery of any of the missing Peking Man original fossils would dramatically change our current understanding of human evolution.”29

On one level, this sentiment is certainly true. If the fossils are simply their dimensions and their physical forms, then certainly Yen is correct that the casts are just as good as the originals. Yet the original fossil clearly carries with it cachet and cultural value beyond its height and breadth; in this sense, such an argument amounts to saying that a copy of the Hope Diamond or the Mona Lisa would be the “same” as the original.

Painted casts of Peking Man skull at the Cenozoic Research Laboratory on a laboratory bench. From Paramount News film, early 1930s. (Film courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History Library and Dr. Milford Wolpoff)

—

“In 1539 the Knight Templars of Malta paid tribute to Charles V of Spain, by sending him a Golden Falcon encrusted from beak to claw with the rarest jewels—but pirates seized the galley carrying this priceless token and the fate of the Maltese Falcon remains a mystery to this day,” reads the introductory text that appears after the opening credits in the 1941 film The Maltese Falcon. It is the story of a treasure hunt for a priceless object and the motivations that fuel that hunt. The “black bird” that Kasper Gutman and Sam Spade search for is that jewel-encrusted falcon, which, by the 1940s, was said to have been covered in a deep black patina to hide the bird’s true value. In the film’s dramatic reveal—where the bird is proven to be a fake—the audience is told that the bird is more myth than fact. In the end, actually finding the bird wasn’t as important as cultivating the belief in what it stood for. The bird, Sam Spade dryly notes, is the “stuff that dreams are made out of.”

Today, the only pieces of the Peking Man in Chinese collections are five teeth and some parts of a skull found in the renewed excavation of the 1950s and 1960s. The Uppsala Museum of Evolution has three teeth from the original excavations in the 1920s; these are considered the “collection’s highlights.” When the tooth was discovered in the boxes of Professor Carl Wiman’s stuff, that tooth, newly reexcavated from the archives, became a significant part of the Peking Man’s story. Like that tooth, Peking Man’s story is one of abrupt beginnings and endings, encounters and losses; it’s a story of details and dramatic events—kind of like The Maltese Falcon, but with fossils.

“As is well known, almost all material from this excavation period (except the original Uppsala teeth) was lost in 1941, and has never been recovered,” Swedish research Dr. Per Ahlberg said in an interview. “After the war, Chinese scientists continued to excavate Zhoukoudian and found some new fossils in the deeper layers. But this new tooth is most probably the last fossil from the ‘classical’ Peking Man excavations that will ever be found.” Ahlberg continued, “We can see many details that tell us about the life of the owner of the tooth, which is relatively small, indicating that it belonged to a woman. The tooth is also rather worn, so the person must have been rather old when she died. Also, parts of the tooth enamel have been broken off, probably indicating that the person had bitten down on something really hard, like a bone or a nut. We should probably now be talking about a ‘Peking Woman’ and not a ‘Peking Man.’” Professor Liu Wu, from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, chimed in with his observations that the canine tooth was fractured but otherwise well preserved: “This is an extremely important find. It is the only canine tooth in existence. It can yield important information about how Homo erectus lived in China.”30

Peking Man’s legacy—his legend, his fame—hinges on his disappearance. It’s as if the paleo world had found a historical parallel for the story of Amelia Earhart; Peking Man captivates its audiences because the ending of its story is a mystery. As history, unresolved stories can be unsettling and deeply unsatisfying. Even Piltdown—with his conspiracies—is a fossil with a better-resolved narrative. Piltdown is a hoax; the perpetrator might still be at historical large, but the fossil’s story has been rather neatly tied up with Kenneth Oakley’s chemical analysis, and Piltdown’s fossils are carefully stored in the fossil vault at the London Natural History Museum. Peking Man, on the other hand, is missing—it’s a paleo-noir cold case in the history of science.

Peking Man teeth with original museum label (Lagreliska Collection). (Science Source)

Perhaps the black bird offers a useful lens for making sense of the life history of the Peking Man fossils. Every aspect of the Peking Man story contains multiple levels. One is its science, of course, but also finding part of the Peking Man collection—even if it is just a tiny part found in archival boxes—provides a compelling narrative aspect, another level, to the Peking Man story. What was lost has now been found.

Today, we know Peking Man through the recently recovered canine tooth and a couple of other molars sent back to Uppsala from Zhoukoudian during those initial excavations—but we know Peking Man better through his plaster casts, photographs, and stories. The fossils are famous because we don’t have them anymore. Peking Man is, indeed, a curious case of celebrity; a fossil made famous by its paleo-noir mystique.

To date, the fossils have not been recovered.

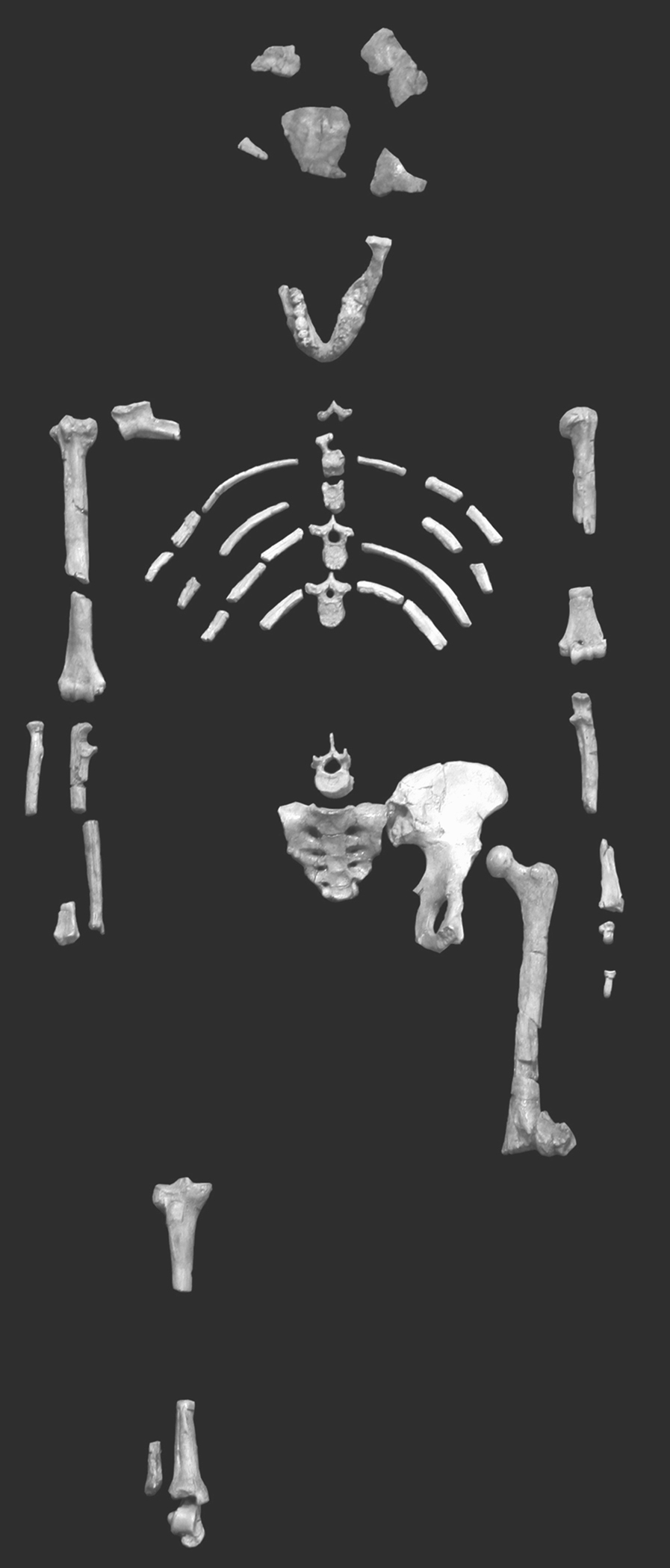

Portrait of Lucy, AL 288-1. (Photo permissions: CC-BY-2.5)