Methods and Instruments of Torture and Execution

It is a serious mistake to consider instruments of torture as quaint relics of the past which can be viewed with amused detachment by those who visit castle dungeons or museums of crime and punishment. Torture, or the threat of it, has long been used as a means of breaking resistance and extracting information; doubtless it will continue to be used until such time as man moves onto a better and higher form of society.

It is sometimes difficult to distinguish between an instrument of punishment and of torture or execution, so we will be fairly ecumenical and not too prescriptive in what we present below. It is likely that all the methods and instruments mentioned below have been employed in London in the past but that is not to say that they are unique to the metropolis. It is also likely that all of them, in similar or adapted form, have extracted their toll of human misery somewhere else in these islands.

Hanging

The earliest judicial hangings simply used the branch of a convenient tree. More permanent arrangements involved uprights and a crossbeam. The victims climbed a ladder and had a rope placed around their necks. When all was ready, the ladders were turned round and removed; hence the victims being ‘turned off ’. In the endless drive for greater efficiency, later on the victims were placed standing on a cart, likewise with a rope around their necks hanging from a crossbeam. The horse would then be whipped and as the cart shuttled away, the prisoners were left dangling in mid-air. In 1760 the device known as ‘the drop’ was introduced, first used at the Tower. Now the victim stood on a trap door on the scaffold. When the bolt was drawn, the trap door opened and the victim fell through to eternity. Some teething problems were encountered but when these were overcome, it was widely believed that the drop brought death to the victim more quickly.

The London Dungeon on Tooley Street, London Bridge, dedicated to the display of punishments from London’s history.

Hanging days were occasions for joyful revelry – at least for those who turned out to watch proceedings if not, of course, for the condemned prisoners, their friends and relations. Death by strangulation was slow – anything up to twenty minutes in some cases although unconsciousness came somewhat sooner. The crowds seem to have enjoyed watching the felon choking out the last few minutes of his life but sometimes they were thwarted in their voyeurism when, for an agreed sum, the hangman allowed the victim’s relations to pull on his legs, thereby shortening his suffering. To present-day tastes, the whole public performance and the rituals that went with it seem barbaric, especially since the victims often involuntarily evacuated their bladders and bowels.

Beheading

Beheading has been carried out with a sword or an axe. Very considerable skill is required by the executioner if beheading is to be done in such a way as to minimise the suffering of the victim. Long and assiduous practice on dummies or animals in slaughterhouses was needed by the axeman because the neck presents only a small target for a rapidly descending axe brought down from over the back of the head. Likewise, decapitation with the sword can only be done effectively after a prolonged apprenticeship. It is in recognition of the fact that an expert wielding the sword or the axe can bring about an almost instantaneous death that these methods have been regarded as the prerogative of the high-born. The lower echelons of society have had to put up with the altogether slower and frequently more uncertain ministrations of the hangman.

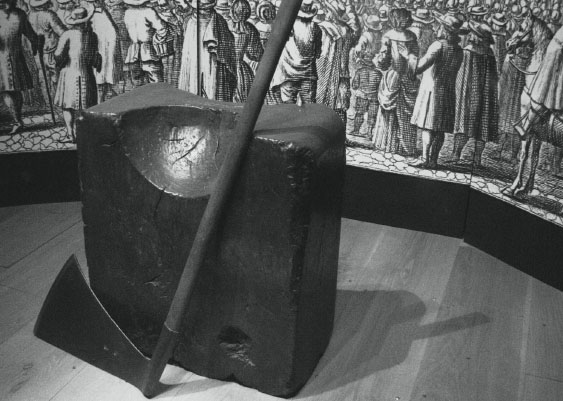

There was nothing very subtle about the headsman’s axe. Its action was basically like that of a chisel, crushing its way through the vertebrae by brute force as the heavy instrument descended on the neck. Its blunt edge is not intended for cutting but for breaking. It was all very well for the headsman to while away his spare time practising, but unfortunately even the most extrovert of operatives sometimes withered under the critical eye of the kind of people who turned up at executions. Some of the spectators were hardened veterans of hundreds of executions and they put the headsman’s performance under almost as much critical scrutiny as they bestowed on the behaviour and demeanour of the person being executed. Under these circumstances, headsmen sometimes became nervous and they might bungle the beheading, needing several blows with the axe to complete the operation. If this happened, it would be to an accompaniment of derisory scoffing from the audience and heart-rending screams of agony from the not-quite deceased. It was clearly in the latter’s interest to have the job completed as quickly and simply as possible and victims frequently offered the headsman money as an incentive to ensure a job well done.

Block and axe in the Tower of London.

When the head was severed, it was normal for the executioner to hold it up for the crowd to see that the deed had been properly completed. Later, the head was sewn back on for the sake of appearances. The executioner would accompany the act by a statement such as, ‘Behold the head of a traitor!’ At least one severed head is supposed to have snarled back a statement such as, ‘You lie, I am no traitor!’ This ritual was important because it provided evidence of death and supposedly prevented an impostor coming forward at a later stage.

The execution of the Earl of Strafford in 1641; a crowd of over 100,000 was reputed to have attended.

The block was of course the axe’s partner in crime and it evolved over the years from a plain log into something specially shaped for its purpose. It was usually about 2ft high and designed so that the head fell off into a waiting basket of sawdust. If the first blow inflicted a deep but not fatal wound, severing the artery, it was by no means unknown for those close by to be sprayed by high-pressure blood.

Death by Burning

This was the punishment largely reserved for heretics. The theory was that they had been guilty of thought-crime, of holding and practising unacceptable religious ideas, and that death by burning was a condign preparation for the fires waiting for them in Hell. The burning was a symbolic destruction of the evil ideas the person harboured as well as the death of the reprobate himself.

Witches and women found guilty of murdering their husbands were also burned to death. It seems almost inconceivable by modern standards, but burning was devised as a method of execution for women to protect their modesty! It was though that public hanging, drawing and quartering would be indelicate as parts of their bodies would be exposed to public gaze.

Death by burning.

The victim was tied to a stake with a rope around her neck and at the agreed moment the executioner ignited the firewood and tugged on the rope. The theory was that the victim would be dead by the time the flames were licking around her body. However, in the case of Catherine Hayes, who was executed at Tyburn in 1726 for killing her husband, the wood flared up so quickly that the executioner had to remove himself before strangulation was complete. The crowd was then treated to the sight of Catherine’s prolonged and excruciating death agonies. The executioner had little option but to pile on more faggots hoping that the conflagration would be intense enough to shorten her sufferings.

Death by Boiling

Perhaps fortunately, the authorities did not often have recourse to this diabolical form of execution. Seemingly the first person to suffer this fate was one Richard Rose in 1531. He was a cook who was found guilty of high treason for poisoning the family and household of the Bishop of Rochester. Seventeen people suffered severely and two actually died. Rose was placed in an iron cauldron of water over a fire which was then brought to the boil. He took two hours to die in full public view at Smithfield. It was assumed that the poisoning was deliberate. Modern scientific techniques might instead have detected poor hygiene standards or even a dose of salmonella.

The horror of death by this singularly unpleasant, but fortunately rare, method was perhaps slightly lessened in later years when the victim was placed in water that was already at boiling point. Would that actually be any better?

Gibbeting

The English were not known to be particularly fastidious when it came to the methods of punishment and execution they employed. However, it does seem that unlike their counterparts in some European countries, they did not very often gibbet people alive. Instead, they usually employed gibbeting as a kind of aggravated punishment with the added bonus that it was believed to be a deterrent to wrongdoing on the part of those whose glance fell on the gruesome remains of some miscreant swaying to and fro in an iron cage caught up by the wind. Certain types of offender – highwaymen and pirates in particular – had their bodies daubed in tar or some other preservative substance after death, whereupon they were placed in chains inside a hanging iron cage and displayed in some conspicuous place such as a crossroads or, in the case of the pirates, a prominent spot near a river frequented by large numbers of passing ships.

The fleshy parts of the gibbeted cadaver and such items as the eyes soon disappeared thanks to the attentions of birds, especially of the crow family, and rats, which were not averse to making their way up the wooden supports into the cage where the corpse provided, literally, easy meat. Such corpses soon became little more than a collection of bones, which often collapsed and often fell out of the cage to gladden the hearts of passing dogs.

The Judas Cradle

Just because no one in English officialdom has ever admitted that this diabolical procedure has been used, we cannot therefore assume that it has not. England had all manner of close links with governments in Western Europe in medieval times and word got about. The Judas Cradle was such a simple, economical and effective means for extracting information that it somewhat stretches the bounds of credibility to think that this device never lurked in the darkest and dingiest dungeon of the Tower of London.

The victim had his hands tied behind his back and was secured in an iron waist ring. He was then hoisted up by a system of winches and pulleys only to be lowered onto the sharp point of a pyramid surmounting a sturdy tripod. The victim was placed in such a way that his or her weight rested on the apex of the pyramid positioned in the anus, in the vagina, under the scrotum or the coccyx. The torturer responded to the requirements of the interrogator by varying the pressure being applied and could rock the victim or make him fall repeatedly on the point.

This instrument was used as a means of punishment in the Royal Navy, whose ships were frequently to be seen around Deptford Dockyard and occasionally in the Pool of London. A somewhat lighter version was used in the Army. The naval cat had a handle of rope or sometimes of wood about 2ft long and 1in in diameter. Each of the nine tails or thongs was ¼in in diameter and 2ft long. They usually had one or two knots along their length.

The crew would be assembled to witness the punishment, with marines standing by with muskets and fixed bayonets. The offender was tied to an upright grating and stripped to the waist. Punishment was then inflicted by the bosun’s mates and the lashes were usually administered in multiples of six. The knots in the tails had the effect of lacerating the skin in a prolonged flogging and on occasions the flesh was stripped away to reveal the bones. When punishment was completed, the offender was cut down and usually swabbed with salt water to stem the bleeding.

The cat was sometimes used in civil prisons.

The Scavenger’s Daughter

On display in the White Tower at the Tower of London is this device also known as ‘Skeffington’s Gyves’. Leonard Skeffington was a Lieutenant of the Tower in the 1530s (though he is more likely to have adapted an existing device than to have invented one himself). Made of iron, this fiendish apparatus had spaces for the neck, the wrists and the ankles and it had the effect of compressing the body of the victim, inducing excruciating pain, especially in the abdominal and rectal areas. Its advocates considered that it induced more pain than the rack. It was probably the ideal torture machine. It was light and easily transported, and the mere sight of it was often enough to persuade a prisoner to cooperate fully with his inquisitors.

Whipping

Whipping was an economical punishment since little capital outlay was required. A common practice was ‘whipping at the cart’s tail’. The offender was stripped to the waist and tied to the back of a horse-drawn wagon. As the horse drew the wagon and the offender slowly through the streets, whipping would be administered at prescribed places, particularly at the scene of the crime. The more serious the offence, the longer the journey around town. This punishment involved public humiliation as well as pain. Sometimes the public were allowed to whip the offender as he passed by where they were standing. Whippings or floggings with a birch were also administered for various misdemeanours in prison.

Tongues that had uttered blasphemous, treasonable or otherwise unacceptable words might be ripped out or have a hole bored in them. The hand of a thief or assailant might be removed. The punishment of time in the pillory might be aggravated by the offender having his ears nailed to the woodwork. Prostitutes sometimes had their noses slit – perhaps this was intended to be bad for their business activities.

Branding

Branding was a handy punishment, combining as it did the administering of pain with the depositing of a permanent visible scar or stigma. Different letters were burned into the flesh to signify different offences. A ‘V’ indicated a runaway servant while ‘T’ was a thief and ‘FA’ was a false accuser. The law banned civil branding in 1829. Vagrants were frequently branded, which often made it difficult for them to ever become gainfully employed.

The Rack

The rack was used in the Tower of London to extort information and ‘confessions’ from, among others, those who thought up the Gunpowder Plot in 1605. The victim was tightly secured to a table and attached to an apparatus which literally stretched him – several inches. The pull exerted was usually comparatively gentle at first but would be intensified by the torturer if he felt that his victim was holding back vital information. Every joint in the arms and legs would be dislocated, the spinal column dismembered and the muscles of the limbs, thorax and abdomen ripped apart. This appalling device served the purposes of the interrogator, the torturer and the executioner.