Social Sanctions

Victorian institutions such as workhouses, hospitals, lunatic asylums and prisons were not intended to be places of joy. They inflicted punishments varying from the mild to the downright cruel and barbaric. In 1861 the census recorded 65,000 people in London institutions, approximately 37,000 males and 28,000 females.

The Workhouse

Our ancient system of poor relief dates from the sixteenth century, when parishes were made legally responsible for looking after their own poor. The funding for this came from the collection of a poor-rate tax from local property owners. However, by the start of the nineteenth century the cost of poor relief was increasing; at the same time, many believed that parish relief was an easy option for those who did not want to work. In 1834 the Poor Law Amendment Act was passed, which was intended to end all outdoor-relief for the able-bodied. Outdoor-relief was to be replaced by one of the most famous institutions of the past – the workhouse.

Around 15,000 parishes in England and Wales were formed into Poor Law Unions, each with its own union workhouse managed by a locally elected Board of Guardians. Hundreds of workhouses were erected across the country. This new Act used the threat of the Union workhouse as a deterrent to the able-bodied pauper. Poor relief would only be granted to those desperate enough to face entering the workhouse – and life inside the workhouse was intended to be as unpalatable as possible.

Food consisted of gruel – watery porridge – or bread and cheese, and inmates had to wear the rough workhouse uniform and sleep in communal dormitories. The able-bodied did work such as stone-breaking or picking apart old ropes called oakum. Workhouses consisted of the old, the infirm, the orphaned, unmarried mothers and the physically or mentally ill. In some cases it also included those who had been wealthy but had fallen on bad times. Entering the workhouse was considered the ultimate degradation.

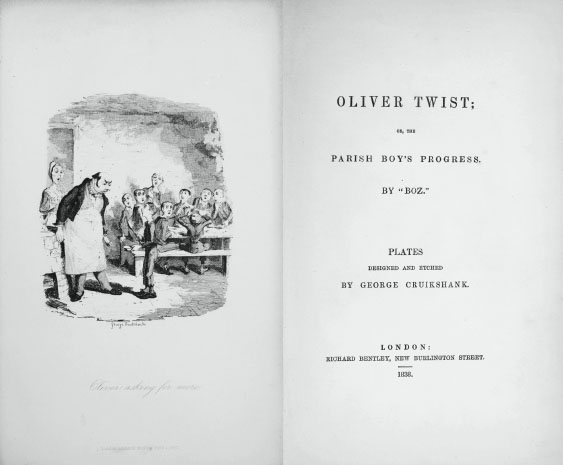

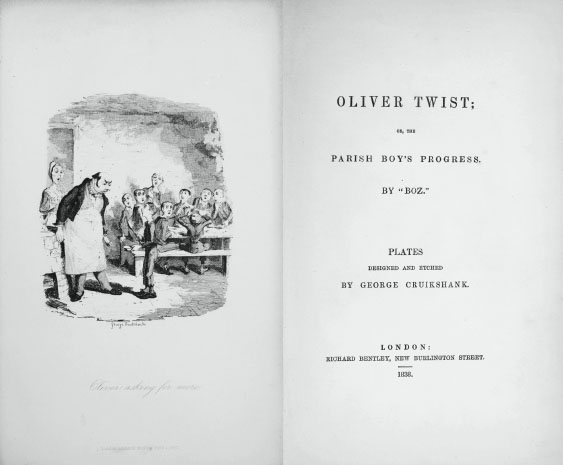

Oliver Twist famously asking for more food.

Describing a workhouse in 1838 in Sketches in London, James Grant commented:

Nothing but the direst necessity has compelled them to take refuge in these places: it is only when... they see absolute starvation staring them in the face, that such individuals have been induced to submit to the alternative of seeking an asylum in a workhouse. And once in, the idea of again coming out, until they are carried out in their coffins, never for a moment enters their mind. When they cross the gate of the workhouse, they look on themselves as having entered a great prison, from which death only will release them. The sentient creations of Dante’s fancy saw inscribed over the gate of a nameless place the horrific inscription, ‘All hope abandon, ye who enter here’.

The following is a summary of the rules drawn up for the conduct of the inmates at the workhouse in Hackney in the 1750s. Anyone not abiding by them could face imprisonment and be would be punished with the utmost rigour. Inmates were expected to observe the saying of prayers and to attend church. Anyone found loitering, begging, swearing or getting drunk was to be punished in the stocks. There was to be no distilled liquors brought into the house, and anyone causing a disturbance by brawling, quarrelling, fighting or using abusive language would lose one day’s meal. For a second offence they would be put into the dark room for twenty-four hours. Inmates refusing to work were to be kept on bread and water, or expelled. Any person pretending to be sick in order to avoid work would appear before a magistrate. Inmates were also expected to clean themselves, wash and mend their clothes, and clean their dishes. Failure to do so meant having to suffer an appropriate punishment.

Institutions such as the workhouse often included sadists amongst the staff. The Times reported on 8 December 1868 that Mrs Wells, the matron of Bethnal Green Workhouse Schools at Leytonstone, came before the Board of Guardians on a charge of cruelty for ill-treating and beating girls placed under her care by the workhouse authorities. Her husband, the master, also had a charge against him for neglect and being drunk on duty.

At Hackney in 1894, Ella Gillespie, one of the school’s nurses, was accused of ‘systematic cruelty’ to the children in her charge – allegedly beating them with stinging nettles and forcing them to kneel on wire netting that covered the hot water pipes. She also deprived them of water and made them drink from the toilet bowls. At night children would lay awake in fear, bracing themselves to face her ‘basket drill’. Then they would be woken from their sleep and made to walk around the dormitory for an hour with a basket on their heads containing their day clothes, receiving a beating if they dropped anything. Gillespie was regularly drunk and in 1893 a local brewery supplied her with nineteen 4½ gallon casks of beer.

Other examples of her brutality included knocking the head of a thirteen-year-old girl against the wall seven times for talking to another girl. This incident happened as two girls were scrubbing the nursery floor, after a third girl entered and accidentally knocked over two scuttles of coal. Furious, Gillespie turned over four pails of water, and rubbed a girl’s head into the wet coal on the floor. On another occasion she struck a girl with a bunch of keys, cutting her head and drawing blood. Many girls gave evidence against her, including thirteen-year-old Elizabeth Fawcett, who stated that Gillespie had slapped her face, pulled her hair and struck her with a frying pan. Alice Payne told how she and other girls were subjected to punishments such as laying naked on the bed whilst being thrashed with stinging-nettles. The evil and sadistic Gillespie was sentenced to five years’ penal servitude.

In 1882 able-bodied men at Mary Place, Notting Hill, performed tasks such as stone-breaking, corn-grinding and oakum picking for fifty to sixty hours a week. The diet was basic and monotonous and smoking was forbidden. No inmate was ever allowed temporary leave from the premises.

The original St James’s workhouse between Poland Street and Marshall Street in Soho was erected in 1725. During the eighteenth century this workhouse was reported to be in a ‘very nasty condition, the stench hardly supportable, poor creatures almost naked and the living go to bed to the dead’. The workhouse was not without its own criminal activity, despite there being little worth stealing. For example, in October 1818 fifty-six-year-old pauper Cuthbert Ramshaw stole a piece of woollen cloth worth 5s which was the property of the Governors and Directors of the Poor. For such ungrateful behaviour Ramshaw was whipped and given three months’ confinement.

Inside and outside of the Old Operating Theatre, Southwark.

In 1818 seventeen-year-old John Dunn, who had spent his whole life as a pauper in the workhouse, stole one coat, a pair of trousers and a waistcoat belonging to James Horwood, master of the workhouse. Dunn, who was probably conditioned to the harshness of life in the institution, also received a whipping.

St Marylebone parish workhouse began operating in 1730. However, by the 1840s the demand for places in the workhouse exceeded 2,000 and with such high numbers there were pressures to economise. In 1856 allegations were made against workhouse staff for beating several young female inmates.

The punishment for being poor was severe enough, without any legal sanctions in addition. Even in death there was no escape, for the corpses of the impoverished were preyed upon by the body snatcher and the anatomist. The demand for corpses gave rise to the grisly activity of the resurrection men – the body snatchers. The only corpses available for medical study were those of hanged murderers. The 1832 Anatomy Act made it an offence to rob graves, so the only other corpses a doctor could legally dissect were the unclaimed bodies of people who had died in hospitals or workhouses. The stigma and fear of the workhouse was bad enough, but it was now made infinitely worse. Workhouses responded differently to the demands for the bodies of their poor. In the 1830s St Giles workhouse (average death rate of 200 per year) delivered 709 of its ‘unclaimed’ poor for dissection, while Marylebone gave up only fifty-eight. The system of delivering corpses of the poor also led to corruption. At St Giles parish in 1841, ‘considerable excitement’ was caused when it was discovered that the workhouse mortuary keeper, who had been bribed, decapitated a smallpox victim’s body.

Social reformer Henrietta Barnett (1851-1936) played an important role in leading the movement to abolish the inhuman institutional care of pauper children and replace it with fostering. In her report, published in The Cornhill Magazine, there were 22,000 children in workhouses and 12,000 in the hateful barrack schools. Details of the care given in workhouses make shocking reading:

The whole nursery has often been found under the charge of a person actually certified as of unsound mind, the bottles sour, the babies wet, cold and dirty... one feeble-minded woman was set to wash a baby; she did so in boiling water, and it died.

‘Bedlam’

The most famous institution for the mentally ill was Bethlem Hospital, or ‘Bedlam’ (now known as the Bethlem Royal Hospital), based in Beckenham, south-east London. Although no longer in its original location, it is recognised as possibly the oldest psychiatric facility in Europe. The present hospital is at the forefront of psychiatric treatment, but for much of its history it was notorious for cruelty and inhumane treatment. Being mad was, in effect, a punishable condition.

The first site of Bedlam was in Bishopsgate Street in 1330. It became a hospital when the first Bethlem lunatics were recorded there in 1403. Conditions were awful and what care existed amounted to little more than restraining patients. Violent or dangerous inmates were manacled and chained to the floor or wall whilst some were allowed to leave and licensed to beg. By the late sixteenth century one inspection reported that there was great neglect, with the cesspit in dire need of emptying and the kitchen drains in need of replacing.

It was common practice in the eighteenth century for people to go to Bedlam to stare at the lunatics and even poke them with long sticks. There were some reforms, including the ending of casual public visiting in the 1770s; however, in 1814 the philanthropist Edward Wakefield was shocked when he encountered a patient:

A stout iron ring was riveted round his neck, from which a short chain passed through a ring made to slide upwards and downwards on an upright massive iron bar, more than six feet high, inserted into the wall. Round his body a strong iron bar about two inches wide was riveted; on each side of the bar was a circular projection; which being fashioned to and enclosing each of his arms, pinioned them close to his sides.

Bedlam, as depicted by William Hogarth.

Bethlem Hospital in 1828.

One patient, James Norris, had suffered this type of treatment for twelve years. Wakefield’s disclosure led to the setting up of a Parliamentary committee to investigate asylums, which in turn revealed some shocking evidence. Here is Wakefield’s description of the women’s galleries:

One of the side rooms contained about ten patients, each chained by one arm or leg to the wall, the chain allowing them merely to stand up by the bench or form fixed to the wall, or to sit down on it. The nakedness of each patient was covered by a blanket-gown only.

Mercifully, the findings at least led to a new start when rebuilding began, including the addition of blocks for criminal lunatics.

However, in 1851 there was a scandal over the death of a patient which led to a further inquiry. This again exposed a number of unpleasant cases of ill-treatment. For example, the case of patient Hannah Hyson typified the worst sort of cruelty and wanton neglect. Her father wrote to the president of Bethlem, Sir Peter Laurie, complaining of his daughter’s treatment. He noted over twenty wounds and lacerations on her body and described how her bones were almost showing through her skin. Tragically, Hannah died shortly after the letter was written.

Hannah’s case was soon followed by that of Ann Morley who complained she had been hit by a nurse, forced to sleep on straw in the basement and hosed down with cold water despite being ill. Anne’s complaints opened the door for other patients who told of their experiences. Some of these were in a skeletal condition, whilst others told of being force fed (which led in at least one case to a man dying).

In 1815 Bethlem was moved to St George’s Fields, Southwark – now the site of the Imperial War Museum – and in 1930 the hospital was moved to the site of Monks Orchard House, Beckenham.

Schools

The most commonly experienced sanction is undoubtedly school punishment. Parliament abolished corporal punishment in state schools in 1986, though the verbal reprimand and the feared detention remain (a staple of school punishment for years). Gone are the days when a good thrashing would be meted out for almost any misdemeanour, or when pupils had to stand on a stool at the back of the class wearing a tall, cone-shaped hat decorated with a large ‘D’ for dunce.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, children were not required to go to school but, by 1899, all children up to the age of twelve officially had the opportunity of going to school. Education depended on how wealthy families were. Rich children could be educated at home by a private tutor or governess; boys were sent to boarding schools such as Eton or Harrow. The sons of middle-class families attended grammar schools or private academies. The only schools available for poor children were charity and Church schools or ‘dame’ schools set up by unqualified teachers in their own homes. Ragged schools were introduced in the 1840s.

In 1854 Reformatory Schools were set up for offenders under sixteen years old. These were very tough places, with stiff discipline enforced by frequent beatings. Young people were sent there for long sentences – usually several years. The schools provided industrial training for juvenile offenders. In 1886 John Tarry appeared before the Old Bailey for assaulting a thirteen year-old girl. His punishment was seven days’ imprisonment, eight strokes with a birch rod and two years in a reformatory school.

Punishment in the Workplace

The extent and regularity of severe and brutal punishment in workplaces, particularly small workshops that employed young children, cannot be exaggerated.

In 1685 Ann Hollis from the City of London was indicted for killing her apprentice, fourteen-year-old Elizabeth Preswick, with a rod of birch. Hollis took the girl upstairs and, with the help of two other girls, held Elizabeth on the bed whilst she whipped her on the ‘back, belly, shoulders and legs’ so much that she passed out. Elizabeth died shortly after. Hollis said that she only whipped her a few times for ‘lying’ and ‘being lazy’. Elizabeth was a ‘sickly girl’ who, it was concluded, had died of a consumption. Clearly this proved to be a fortunate decision for Hollis, who was acquitted.

The Old Bailey from the Viaduct public house.

A particularly evil employer was the infamous Sarah Metyard and her daughter, Sarah Morgan Metyard. Metyard senior employed young girls from parish workhouses to work as milliners. In 1758, thirteen-year-old Anne Naylor was subjected to dreadful cruelty. Anne and her sister were apprenticed as milliners to Sarah Metyard along with five other young girls (all of whom had come from workhouses). Anne was described as being of ‘a sickly disposition’ and therefore found the work difficult; she could not keep up with the other girls. This singled her out and made her the object of the fury of the Metyards. They punished Anne with such barbarity and repeated acts of cruelty that she decided to flee. Unfortunately, however, she did not get far: she was brought back, confined in an upstairs room and fed with little more than bread and water. For such a sickly child this could only weaken her further. Nonetheless, she seized another chance to escape – but was again returned. Poor Anne was thrown back into her prison, where she awaited the fury of the Metyards. As the old woman held her down the daughter began to beat Anne savagely with a broom handle. They then tied her hands behind her and fastened her to door, where she remained for three days without food or water. The other apprentices were not allowed to go anywhere near the room on pain of punishment. Alone, bruised, exhausted and starved, her speech failed her. By the fourth day she was dead.

Despite the dire warnings, some of the other girls saw her body tied with cord and hanging from the door. They cried out to the sadistic women to help Anne. The daughter ran upstairs and proceeded to hit the dead girl with a shoe. It was apparent that there was no sign of life and pathetic attempts were made at reviving her. One of the young apprentices, Philadelphia Dowley, acted as a witness four years later at the trial of the Metyards at the Old Bailey (July 1762). When asked why Anne tried to run away she replied, ‘because she was... so ill. She used to be beat with a walking stick and hearth brooms by the mother, and go without her victuals’. Another witness, Richard Rooker, had been a lodger at Metyard’s house. He told of the grisly attempt to conceal the crime, the revelation of other murders and how Metyard’s daughter had told him with great reluctance what happened. There was a reluctance to announce the death and bury Anne as it would be clear from the state of her body that she had starved to death. Instead, Anne’s body was carried upstairs into the garret and locked up in a box, where it was kept for upwards of two months until it ‘putrefied, and maggots came from her’. The Metyards cut the body into pieces and then burned one of the hands in a fire. They then proceeded to dump the remains of the body near Charterhouse Street. The remains were discovered by a nightwatchman, who reported it to the ‘constable of the night’.

Four years had passed since Anne’s murder and it seemed that she would be denied justice. However, the continual arguments between Metyard senior and her daughter resulted in frequent beatings for young Sarah Metyard, who wrote a letter to the overseers of Tottenham parish informing them about the whole affair and exposing her mother as a murderer. Both mother and daughter were subsequently arrested and indicted for the wilful murder of Anne and her eight-year-old sister, Mary Naylor. Both mother and daughter were executed at Tyburn and then taken to the Surgeon’s Hall for dissection.

Cock Lane, near to where Anne Naylor’s remains were dumped.

Another notorious case of physical abuse of servants in the eighteenth century concerned one Elizabeth Brownrigg. Yet again the unfortunate victims were orphaned young girls. Elizabeth Brownrigg was married to James Brownrigg, a plumber who, after spending seven years in Greenwich, came to London and took a house in Flower-de-Luce Court, Fleet Street. Elizabeth, a midwife, was appointed to look after women in the poorhouse run by the parish of St Dunstan-in-the-West. On one particular occasion, she had received three apprentices who she took into her own house where they did domestic service in order to learn a trade. Mary Mitchell was one of the apprentices appointed in 1765, and Mary Jones from the Foundling Hospital soon followed her. Jones quickly fell victim to Brownrigg’s own brand of punishment: she was made to lie across two chairs in the kitchen while Brownrigg whipped her with such ferocity that she was ‘obliged to desist through mere weariness’. Brownrigg would then throw water on her victim and often thrust her head into a pail of water. Poor Mary Jones had no one she could turn to. Her suffering was unimaginable.

Eventually she managed to escape, and found her way back to the Foundling Hospital where she told of her beatings. A surgeon examined her and found her wounds to be of a ‘most alarming nature’. A solicitor wrote on behalf of the governors to Elizabeth Brownrigg’s husband, James, threatening prosecution. Typically, the letter was completely ignored and the governors did not follow up the case. Unfortunately Mary Mitchell, who was still in the service of Brownrigg, was subjected to similar cruelty over the period of a year. She too managed to escape – but ran into the younger son of the Brownrigg’s (they had sixteen children) during her flight and she was forced back into the house where her suffering intensified.

Tragically another girl with an infirmity, Mary Clifford, joined the Brownrigg household. She was frequently tied up naked and beaten with a hearth broom, a horsewhip or a cane. In addition, she was made to sleep in a coal cellar and was almost starved to death. She became so desperate with hunger that she broke into a cupboard for food – and paid a terrible price. For a whole day she was repeatedly beaten with the butt-end of a whip. A jack-chain was put around her neck and tied to the yard door: it was pulled as tight as possible without actually strangling the girl.

Another sadistic punishment that Brownrigg inflicted on the girls was to tie them to a hook in the timber beam and horsewhip them. Eventually Mary Clifford told of her treatment to a French lady who was staying in the house. When the woman confronted Brownrigg with this, she flew at Mary Clifford with a pair of scissors and cut her tongue in two places. Finally, when Mary Clifford’s stepmother went to visit her on 12 July 1767, the tyranny of the Brownriggs came to an end. The stepmother was refused entry by one of the servants, who had been instructed to deny that the girl was there. The stepmother was not satisfied and persuaded Brownrigg’s next-door neighbour to post one of his servants, William Clipson, to watch the Brownrigg’s house and yard. Clipson saw a badly beaten and half-starved girl in the yard and reported it to the overseer of St Dunstan’s, who went to the house and demanded that the Brownriggs produce Mary, which they did after an altercation. Mary Clifford was eventually found locked in a cupboard. Her stepmother described her as being in:

The sadistic Elizabeth Brownrigg flogging a servant girl.

a sad condition, her face was swelled as big as two, her mouth was so swelled she could not shut it, and she was cut all under her throat, as if it had been with a cane, she could not speak; all her shoulders had sores all in one, she had two bits of rags upon them.

After much suffering over too long a period, the parish authorities finally took some action: James Brownrigg was arrested, although his wife and elder son escaped with a gold watch and a purse of money. Both Mary Jones and Mary Clifford were taken to St Bartholomew’s Hospital where Mary Clifford died a few days later. A landlord later informed on Elizabeth Brownrigg and her son, and they were duly arrested and kept in Newgate Prison. In her defence Brownrigg stated that, ‘I did give her several lashes, but with no design of killing her; the fall of the saucepan with the handle against her neck, occasioned her face and neck to swell; I poulticed her neck three times, and bathed the place, and put three plaisters to her shoulders’. However, Mr Young, the surgeon, disputed that Mary’s neck injury could have been caused by a saucepan handle.

Elizabeth’s Browning’s skeleton.

Anatomy Theatre, Surgeon’s Hall.

When Brownrigg went to Tyburn to be executed the mob were outraged and vented their anger by pelting her with anything they could get their hands on. After her execution her body was cut down and taken to Surgeon’s Hall where, after dissection, it was hung for people to see.

Elizabeth Wigenton of Ratcliff was hanged in September 1681 for a similar murder. Wigenton, a coat maker, had taken thirteen-year-old Elizabeth Houlton as an apprentice. One day Wigenton fetched one John Sadler to hold the girl, who was tied up and flogged with ‘a bundle of rods so unmercifully, that the blood ran down like rain till the girl fainted away and died soon after’. Both Wigenton and Sadler were convicted of the murder and condemned to hang.

Caning apprentices was not uncommon. In the absence of a universal educational system, prior to the nineteenth century apprenticeships were the ways in which young boys acquired a craft. Many apprentices came into London from elsewhere and were often introduced to a harsh regime. It was not surprising that there was a high drop-out rate. In the London Livery Co., an apprentice was subject to the company’s discipline, as well as to the daily supervision of his master; offences against his master were punished by whippings administered in the company hall. In 1630 the Spectacle Makers’ Ordinances stated that:

...if any Apprentice shall misbehave himself towards his Master or Mistress... Or be any Drunkard haunter of Taverns, Ale Houses, Bowling Alleys or other lewd and suspected Places of evil Company... he shall be brought to the Hall of the said Company... and there these or such like notorious faults justly proved against him before the Court of Assistants... (he) shall be stripped from the middle upwards and there be whipped...

The practice continued centuries later. In 1848 John Harding was indicted at the Old Bailey for cutting and wounding his apprentice, Edward Jobling, who said that Harding had grabbed him by the collar and struck him many times with a cane. Jobling said that ‘he beat me a great deal of good, I felt the blood immediately he had caned me; I felt it with my hand, looked at it about five minutes after – when he went up stairs, I undid my clothes, and saw the blood’.

Karl Marx (1818-1883) saw the cruelty and exploitation in the system of parish workhouses farming children out to work, often to cruel employers. He wrote that:

The small and nimble fingers of little children being by very far the most in request, the custom instantly sprang up of procuring apprentices from the different parish workhouses of London... Many, many thousands of these little, hapless creatures were sent down into the north, being from the age of 7 to the age of 13 or 14 years old. The custom was for the master to clothe his apprentices and to feed and lodge them in an ‘apprentice house’ near the factor... Cruelty was, of course, the consequence... they were flogged, fettered and tortured in the most exquisite refinement of cruelty... they were in many cases starved to the bone while flogged to their work and... even in some instances... were driven to commit suicide.