In December 1967

Time magazine noted that

Bonnie and Clyde was a ‘popular success’ (Kanfer 1971: 333). In fact, while the film was widely debated in the press and perceived as a cultural phenomenon, the box office takings of its first release in August 1967 were limited, and it was nowhere to be seen on

Variety’s end-of-year list of the twenty top-grossing movies of 1967 (Steinberg 1980: 25). Only when the strong media response motivated Warner Bros. to re-release the film in February 1968 did it become a major hit with total rentals of $23m (see Biskind 1998: 38–41, 45–6). Taking the 1968 earnings into account,

Bonnie and Clyde appears at no. 4 in a revised list of the top-grossing movies released in 1967 (see

appendix 1). However, the breakaway hit of 1967 was what

Time described as ‘an alternately comic and graphic close-up of a 19-year-old boy whose central fantasies come terrifyingly true’ (Kanfer 1971: 324). Released late in the year,

The Graduate, went on to earn rentals of $44m, mostly in 1968.

Let us try to put this figure into perspective. ‘Rentals’ refers to the money that cinemas pay to distributors for film hire; rentals usually amount to between 40 per cent and 60 per cent of the box office gross, that is the money paid by cinemagoers for tickets. Box office takings for

The Graduate were $105m (

Variety 2000: 65). In 1968, the year

The Graduate made most of its money, total box office revenues from all films in all movie theatres in the US were $1,045m (Finler 2003: 377). Thus,

The Graduate took in every tenth dollar spent on movie tickets in 1968. In that year, the major studios (Columbia, Fox, MGM, Paramount, United Artists, Universal and Warner Bros.) released 177 films, including both US-produced films and imports; independent distributors, such as Embassy, the company behind

The Graduate, released another 277 films (Finler 2003: 366–7). In addition to this total of 454 films, there were many films like

The Graduate which had been released in 1967 (or even earlier) but were still in circulation in 1968.

The Graduate, then, prevailed against enormous competition.

Another way of appreciating the enormity of the film’s success is to calculate the number of tickets it sold. The average ticket price in 1968 was $1.31, which means that 80m tickets were sold for the movie. This was equivalent to 40 per cent of the total American population (Wattenberg 1976: 8). However, this does not mean that four out of ten Americans saw the film, because observers at the time noted that many people watched the film several times (Alpert 1971: 405).

It was also noted that the audience for The Graduate was predominantly a young one. This is not surprising since young people were the main cinema-ticket buyers in the late 1960s. A 1967 survey for the film industry’s main trade organisation, the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), revealed that ‘half of the United States population 16 years and older almost never goes to the movies’ (Warga 1968: 1). Those who did attend frequently (that is once a month or more) were mostly young; only 18 per cent of the total sample, but 78 per cent of 16-20-year-olds were frequent cinemagoers. Out of all the tickets purchased by those aged 16 and older, almost 30 per cent were bought by 16-20-year-olds, 18 per cent by 21-24-year-olds and 10 per cent by 25-29-year-olds; hence 58 per cent of tickets were bought by those aged 16–30. What is more, youth and older adults had strongly divergent opinions about movies: ‘Objections to the fact that movies deal more explicitly with sex split the population at about 30 years of age’; people under 30 were largely in favour of such explicit treatment, those over 30 mostly were not (Warga 1968: 14). Thus a film like The Graduate, with its (by the standards of the time) fairly explicit depiction of the affair between a young man and an older, married woman, was dividing the nation, with youth clearly on its side and older generations largely opposed. (A similar division of public opinion was noted with respect to violent films such as Bonnie and Clyde.)

The above discussion suggests not only that

The Graduate was mostly seen by young people, but also that most young people saw

The Graduate, often several times. The film’s impact on American youth does not end here. Its soundtrack, recorded by Simon and Garfunkel, was the second biggest-selling album of 1968, and ‘Mrs Robinson’ (the name of the film’s older woman) one of the ten top-selling singles of the year (

People 2000: 220, 224). It would seem, then, that

The Graduate was at the very heart of American youth culture in 1968. In this chapter, I shall first discuss 14 films from 1967 to 1976 which achieved a similar level of success. I shall then identify the 14 biggest hits from 1949 to 1966, and compare them to the ones from 1967–76.

The New Hollywood Top 14, 1967–76

Almost every year from 1967 to 1976 saw the release of one or more breakaway hits whose success was of a similar magnitude to that of

The Graduate (see

appendix 1):

| 1967 |

The Graduate (with rentals of $44m and a box office gross of $105m) |

| 1969 |

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid ($46m/$102m) |

| 1970 |

Love Story ($49m/$106m) and Airport ($45m/c.$80m) |

| 1972 |

The Godfather ($87m/$135m) and The Poseidon Adventure ($42m/$85m) |

| 1973 |

The Exorcist ($89m/$165m), The Sting ($78m/$156m) and American Graffiti ($55m/$115m) |

| 1974 |

The Towering Inferno ($49m/$116m) and Blazing Saddles ($48m/$120m) |

| 1975 |

Jaws ($130m/$260m) and One Few Over the Cuckoo’s Nest ($60m/$112m) |

| 1976 |

Rocky ($57m/$117m) |

Due to inflation, the figures from the late 1960s are not directly comparable to those of the mid-1970s; the average ticket price rose from $1.20 in 1967 to $2.13 in 1976 (Finler 2003: 379). Nevertheless, even an inflation-adjusted tabulation lists the above fourteen films as the greatest hits of the period 1967–76 (see

appendix 2).

This section deals with the commercial, cultural and critical status of these superhits, which, for simplicity’s sake, I will refer to as ‘the New Hollywood Top 14’. As we will see, these fourteen films are closely connected to trends among the annual top ten, in so far as their breakaway success exerted a strong influence on future hit patterns, while this success in turn derived partly from already existing trends. Among other things, this means that the results of my analysis of superhits would not change substantially if I enlarged the group of films under investigation from 14 to 20 or 30.

The market share of each of the Top 14 ranges from 5 per cent to 12 per cent. In 1976, for example, Rocky’s box office earnings of $117m made up 6 per cent of all the money ($1,994m) spent on the purchase of movie tickets during that year (Finler 2003: 377). The strongest concentration of ticket purchases on superhits occured in 1973. Between them, The Exorcist, The Sting and American Graffiti earned $436m, which was 29 per cent of all box office takings in 1973; this means that almost three out of every ten cinema tickets bought in 1973 were purchased for one of these films.

Furthermore, like The Graduate, all of the Top 14 reached a substantial portion of the American population. For example, with an average ticket price of $2.13 in 1976 (Finler 2003: 379), Rocky’s box office take of $117m was equivalent to 55m tickets; this in turn was equivalent to about a quarter of the American population at the time. With a gross of $260m and an average ticket price of $2.05 in 1975, Jaws sold 127m tickets, which was equivalent to an astonishing 60 per cent of the American population. While this does not mean that three out of five Americans actually saw the film at the cinema (because no doubt many saw it several times), the ability of superhits such as Jaws to lure large segments of the American population into cinemas is impressive.

Many of the Top 14 also had spectacular ratings when they were shown on television. The

Love Story broadcast on 1 October 1972 had a 42 rating, that is, 42 per cent of all households were tuned in (Steinberg 1980: 32). Except for the

Bob Hope Christmas Show of 1970 and the final episode of

The Fugitive in 1967,

Love Story was the most popular television programme in American history up to this point (

People 2000: 162). The record audience for

Love Story was matched by

Airport when it was broadcast a year later. Furthermore,

The Godfather (shown in 1974),

The Poseidon Adventure (1974),

Jaws (1979),

Rocky (1979),

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1976),

The Sting (1978) and

The Graduate (1973) all had ratings in excess of 30 (Steinberg 1980: 31–3). As of 1979, five of the Top 14 were among the ten top-rated theatrical movies ever shown on television, and the only made-for-TV movie that outdid them was the mini-series

Roots (1977) (Steinberg 1980: 31–2;

People 2000: 162).

As with The Graduate, there are yet more ways in which these films resonated across American culture. The following soundtracks were placed in the top ten of Billboard’s annual album charts: Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (no. 8 in 1970), American Graffiti (no. 6 in 1974) and The Sting (no. 9 in 1974) (People 2000: 224). There also were more singles taken from the soundtracks of movie hits. ‘Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head’ from Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, for example, was the fourth best-selling single of 1970 (People 2000: 220).

Another indicator of the resonance the Top 14 had across American culture is the fact that nine of the fourteen were based on recently published, often very popular novels. The films drew on the popularity of these novels, which in turn profited from the popularity of the films. This mutually beneficial relationship resulted in increased sales both of cinema tickets and of books (in a similar fashion, ticket sales and soundtrack as well as singles sales were also mutually reinforcing). There was probably only a limited impact on ticket sales figures in the case of The Graduate (the original novel by Charles Webb was published in 1963), One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (Ken Kesey, 1962), The Poseidon Adventure (Paul Gallico, 1969) and The Towering Inferno (based on two books, Richard Martin Stern’s The Tower, 1973, and Thomas N. Scortia and Frank M. Robinson’s The Glass Inferno, 1974). However, the other five films profited hugely from the best-seller status of the novels they were based upon. Arthur Hailey’s Airport had been the best-selling fiction hardback of 1968; Mario Puzo’s The Godfather had been no. 2 in 1969, Erich Segal’s Love Story no. 1 in 1970, William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist no. 2 in 1971 and Peter Benchley’s Jaws no. 3 in 1974. Once the films had come out, all of these novels sold millions more copies in paperback, usually with cover designs that tied them in with the movies. Indeed, four of these novels soon made it into the top ranks of the list of best-selling books in the US between 1895 and 1975. With 12.1m copies sold in hardback and paperback, The Godfather was the highest-ranked fiction title on this list at no. 6, closely followed by The Exorcist (11.7m copies, no. 7), Love Story (9.9m, no. 12) and Jaws (9.5m, no. 14); Airport sold 5.5m copies (see Hackett & Burke 1977: 10–11).

In various ways, then, the Top 14 were at the centre of American film culture between the late 1960s and the mid-1970s. They generated a substantial share of the film industry’s income from ticket sales, each attracting between a quarter and half of the American population to its screenings. The majority of these films were among the top-rated movies ever shown on television, reaching 30–40 per cent of all American households this way. Most of the breakaway hits were tied-in either with a best-selling soundtrack or a best-selling novel.

In this way the extraordinary status of breakaway hits can be quantified. Less quantifiable is the equally important impact each of these films had on future film production, and also on the future film selections made by movie audiences. It is reasonable to assume that the film industry tries to copy breakaway hits, either by imitating them wholesale or by extracting and combining key elements from several hits (see Altman 1999: 38). Similarly, most cinemagoers probably try to find films which can be expected to replicate the enjoyment they experienced with previous films. Since the success of films depends to a large extent on positive word-of-mouth (see De Vany 2004), the biggest hits are the films that were enjoyed by most people and that therefore provide the model for their future film choices.

It is to be expected, then, that every big hit sparks off a wide range of imitations and combinations, many of which will in turn become big hits. This effect can be observed when examining the annual top ten lists of the period (see

appendix 1). To begin with, the enormous success of

The Graduate in 1967/68 established Dustin Hoffman as a new superstar, who was ranked from 1969 to 1972 and then again in 1976 as one of the ten top box office attractions by American exhibitors in the annual star poll conducted by Quigley Publications (Quigley’s star rankings often registered box office hits with a one-year delay; see Steinberg 1980: 60–1). Although he played diverse roles in diverse films rather than replicating the model of

The Graduate, Hoffman’s presence was perceived to be a key factor in the success of

Midnight Cowboy (the third highest-grossing film of 1969),

Little Big Man (6th/1970),

Papillon (4th/1973) and

All the President’s Men (5th/1976) as well as films outside the annual top ten.

Another element of

The Graduate which became central to later hits was its pop soundtrack. During the preceding decade, the only best-selling albums generated by Hollywood’s superhits featured showtunes or orchestral scores, whereas several smaller hits, mostly star vehicles for Elvis Presley and the Beatles, were associated with top-selling rock and pop records (see

appendix 3 as well as the singles and album charts in

People 2000: 218–9, 223; see also Smith 1998, and Denisoff & Romanowski 1991). After

The Graduate, a wide range of pop, rock and blues songs were featured in, among many other hit movies,

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1st/1969),

Midnight Cowboy (3rd/1969),

Easy Rider (4th/1969; the film’s soundtrack became the seventh best-selling album of 1970) and

American Graffiti ürd/1973) as well as the documentary

Woodstock (5th/1970) and the musicals

Lady Sings the Blues (10th/1972; the no. 5 album of 1973),

Tommy (10th/1975) and

A Star is Born (2nd/1976; the no. 3 album of 1977) (

People 2000: 224).

More generally, it is likely that the enormous success of

The Graduate encouraged both audiences and filmmakers to shift their attention away from the female protagonists as well as the mostly past and foreign settings so dominant in mid-1960s superhits (most notably in

Cleopatra, My Fair Lady,

Mary Poppins and

The Sound of Music; see

appendix 3) towards male protagonists and the contemporary American scene. There is also the possible influence of the film’s ambiguous ending, in which the lovers are finally united but seem unsure about each other and their future, on later hits emphasising the problems and failure of romantic relationships, such as

Funny Girl (the highest-grossing film of 1968),

Goodbye, Columbus (10th/1969),

Carnal Knowledge (8th/1971),

The Last Picture Show (9th/1971),

Cabaret (6th/1972),

The Way We Were feth/1973),

Shampoo 3rd/1975) and

A Star is Born (2nd/1976).

By combining the outlaw antics of

Bonnie and Clyde (5th/1967) with the comedy of

The Odd Couple (3rd/1968), in 1969

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, together with

Midnight Cowbody and

Easy Rider, turned the often comic and in places very touching interaction between two male friends (in the above cases mostly on the wrong side of the law) into a successful formula for Hollywood hits. The most direct imitation, once again featuring Paul Newman and Robert Redford as sympathetic criminals, was

The Sting (2nd/1973), yet similar ‘buddy’ relationships could also be found, for example, between two policemen in

The French Connection (3rd/1971), between two prisoners (played by Steve McQueen and Dustin Hoffman) in

Papillon (4th/1973) and between two reporters (Redford and Hoffman) in

All the President’s Men (5th/1976). Further variations include the black sheriff and his white deputy in

Blazing Saddles (2nd/1974), and the groups of friends in

M*A*S*H (3rd/1970) and

Catch-22 (9th/1970) as well as

Deliverance (4th/1972), also the men who grow to be friends in

Jaws (1st/1975) and

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (2nd/1975). Many other hit films from the period – ranging from

The Godfather to disaster movies and cop films – focused on friendships or partnerships between men. This was not unprecedented but it became more pronounced than ever before in the years following

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. The influence of this pattern may even be seen in the central relationships between a grown man and a tomboyish girl in

True Grit (8th/1969),

Paper Moon (8th/1973) and

The Bad News Bears (7th/1976), and between ‘Dirty Harry’ and his female partner in

The Enforcer (8th/1976).

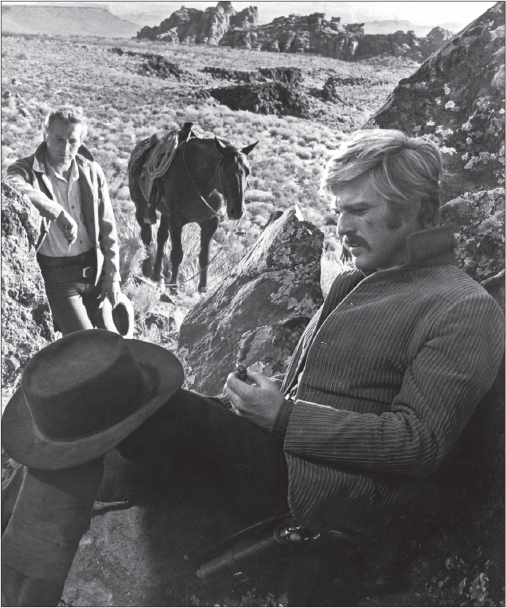

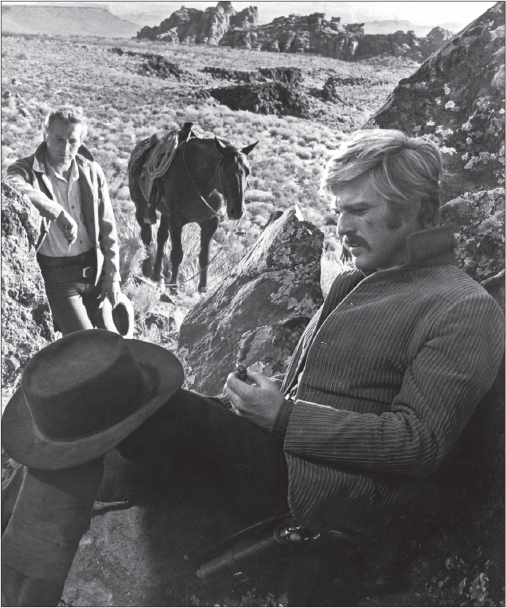

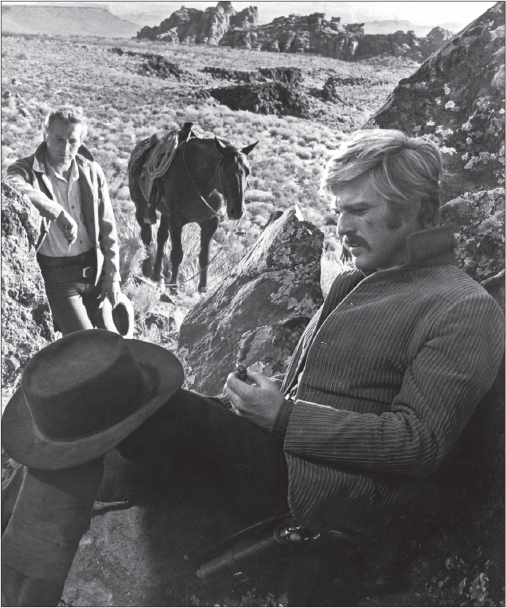

FIGURE 2 Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (George Roy Hill, 1969)

Replicating the abrupt violent ending of Bonnie and Clyde, in which the two protagonists are massacred, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, together with Easy Rider, also confirmed the violent death of one or more of the protagonists as a key ingredient for many movie hits during this period, including The Poseidon Adventure (2nd/1972), The Exorcist CLst/1973), Last Tango in Paris (7th/1973), Earthquake (4th/1974) and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (2nd/1975). Other hits featured protagonists dying from illnesses, including Midnight Cowboy (3rd/1969), Love Story CLst/1970) and Lady Sings the Blues (10th/1972). While the death of protagonists was also a staple of hits before the late 1960s, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and other New Hollywood successes tended to foreground its meaninglessness. Earlier hits such as The Ten Commandments provided meaning for the deaths of protagonists by emphasising that they had led a full life and death was its natural conclusion. Furthermore, religious films such as The Ten Commandments and The Robe emphasised that a glorious afterlife awaited those who died. If protagonists met an early, violent death, it was mostly because they died in the line of duty, perhaps even sacrificed themselves for a good cause (as in many war films). Death might also be the only way for lovers to be united, as in Cleopatra, and even in non-religious films it was not an absolute end, because the dead would live on in their children (as they do in Doctor Zhivago). While such comforting depictions of death did not disappear altogether, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid suggested that abrupt and pointless death was not, as one might assume, putting audiences off, but instead seemed to appeal to them.

Moving on to

Airport in 1970, we can see that one of the elements that made the film such an enormous hit in 1970 was the fact that it featured two near-disasters (an on-board explosion which almost destroys a packed airplane and an obstacle blocking the plane’s emergency landing). Filmmakers extracted this element, exaggerated it and moved it to the centre of subsequent productions (see Roddick 1980). In addition to several less successful films, this resulted in four big hits over the next four years:

The Poseidon Adventure (2nd/1972, set on a sinking ocean liner),

The Towering Inferno CLst/1974, set in a burning skyscraper),

Earthquake (4th/1974, set in an earthquake-ravished city) and

Airport 1975 (7th/1974, a return to the original setting); due to the large-scale destruction brought to New York by the eponymous monster,

King Kong (3rd/1976) could also be added to this list.

Furthermore, Airport’s focus on the day-to-day operations of a large-scale organisation, on the place of key individuals within that organisation and on their professional skills became an important model for numerous subsequent hits. Before the late 1960s, this ‘procedural’ focus could mainly be found in certain war movies and in the James Bond series, in science fiction and crime films (indeed, I have borrowed the term ‘procedural’ from writings on crime fiction; the police procedural has been one of the dominant trends in crime novels and crime movies since the 1940s; see Wilson 2000: chs. 2–3). In the wake of Airport’s breakaway success an emphasis on organisational hierarchies and professional procedures could be found in many top-ten hits (including several of the Top 14), ranging from subsequent disaster movies and further Bond, crime and war films to movies as diverse as the musical A Star is Born, which dealt with the music industry, and the newspaper drama All the President’s Men. Furthermore, several hits highlighted the procedural dimension of activities taking place outside organisational frameworks, for example river rafting in Deliverance (4th/1972), survival in the wilderness in Jeremiah Johnson (5th/1972), confidence tricks in Paper Moon (8th/1973) and maverick science in Young Frankenstein (3rd/1974).

Also in 1970, the success of

Love Story, with its cross-class romance between the scion of an old WASP family and the daughter of an Italian immigrant, confirmed an important trend already under way since 1967 – the centrality of ethnic American characters (see Erens 1984: 262–78). Previously, this had been a feature mainly of Second World War combat movies with their ethnically-mixed platoons (see Basinger 1986), but in the late 1960s hit movies, including many of the Top 14, across a range of genres came to be populated with Americans from ethnic minorities. Italian-American characters could be found in leading roles in films ranging from

Midnight Cowboy (3rd/1969) to

The Godfather Part II (6th/1974) and Jewish-Americans in films such as

Goodbye, Columbus (10th/1969). Furthermore, actors who through the publicity surrounding their off-screen lives and also, to some extent, through their looks were identified as Jewish-American or Italian-American (even if they did not play ethnically-marked characters in all of their films) rose to the top from 1967 onwards (see Levy 1989: 39–41, and Jarvie 1990). In addition to Dustin Hoffman, these included Barbra Streisand, who starred in

Funny Girl (1st/1968),

Hello, Dolly! (5th/1969),

The Owl and the Pussycat (10th/1970),

What’s Up, Doc? (3rd/1972),

The Way We Were feth/1973),

Funny Lady (8th/1975) and

A Star is Born (2nd/1976) as well as several lesser hits, and was listed as one of Quigley’s top-ten box office attractions in seven out of nine years from 1969 to 1977 (Steinberg 1980: 60–1). It is worth mentioning that Streisand was also one of the most successful recording artists of the 1960s and 1970s, with, for example, three albums in the top ten for 1964 and one each in 1966, 1969 (the soundtrack for

Funny Girl) and 1977 (A

Star is Born), as well as the best-selling single of 1974 (‘The Way We Were’) and the fourth best-selling single of 1977 (‘Love Theme from

A Star is Born’) (

People 2000: 220, 223–4).

Al Pacino’s hits included the Godfather movies and Dog Day Afternoon (4th/1974), and he made Quigley’s top ten from 1974 to 1977. Walter Matthau starred in The Odd Couple (3rd/1968), Hello, Dolly! (5th/1969), Cactus Flower (9th/1969) and The Bad News Bears (7th/1976), and made Quigley’s top ten in 1971. Gene Wilder starred in Blazing Saddles 2nd/1974), Young Frankenstein (3rd/1974) and Silver Streak (4th/1976) but was not ranked in the top ten by American exhibitors, whereas both Mel Brooks (in 1976–77) and Woody Allen (1975–77) made Quigley’s list, although their star vehicles did not feature in the annual top ten (Brooks only had a supporting role in Blazing Saddles). Most of these distinctly ethnic actors started their film careers after 1966, and none was considered a major box office attraction before The Graduate made Hoffman a star.

Thus, by offering new models for future film production and for the audience’s future film choices or by enhancing existing trends, individual breakaway hits such as

The Graduate, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Airport and

Love Story had a strong influence on American cinema. In addition, the majority of the Top 14 also had enormous prestige and were celebrated, both by the film industry itself and by the press, as major artistic achievements, while also being identified as all-time audience favourites in several polls. The immediate impact made by

The Graduate is particularly striking. It was on the annual ‘Ten Best’ list (including both American and foreign films) of the

New York Times (Steinberg 1980: 174); won Best Direction at the New York Film Critics Awards for 1967 (1980: 269); was named as one of the ten ‘Best English-Language Films’ of the year by the National Board of Review (1980: 281); won Golden Globes from the Hollywood Foreign Press Association for Best Musical/Comedy as well as Best Director, Best Actress and Most Promising Newcomer (both male and female) (1980: 294); was chosen as the Best-Written American Comedy by the Writers Guild of America (1980: 314), given the award for Best Director by the Directors Guild of America (1980: 320) and nominated for seven Academy Awards, winning the one for Best Director (Elley 2000: 337). What is even more remarkable is that, within a few years,

The Graduate was considered one of the all-time greats. In 1970, it was selected as one of the ten best films (both American and foreign) of the 1960s by

Time magazine (Steinberg 1980: 178); and in two

Los Angeles Times surveys conducted that year, both the newspaper’s readers and a group of filmmakers voted

The Graduate the best film of the 1960s (again both American and foreign films were being considered) (1980: 145). When the University of Southern California asked a panel of American filmmakers and critics in 1972 to name ‘the most significant movies in American cinema history’, that is ‘films which gave new concepts and advanced the art and technique of filmmaking’,

The Graduate made it into the top thirty (1980: 186–7). Finally, in a 1977

Los Angeles Times readers’ poll about the best American films of all time,

The Graduate came in at no. 14 (1980: 189).

The Graduate was by no means alone among the Top 14 in receiving such recognition. The 1977

Los Angeles Times list also featured

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, The Godfather and

Rocky in the top twenty. When the American Film Institute (AFI) conducted what was probably the largest survey of its kind in 1977, asking its 35,000 members for the greatest American films ever, the top fifty included

The Sting, Rocky, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Jaws, The Graduate, The Godfather and

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (Steinberg 1980: 144). In addition to

The Graduate, The Godfather and

American Graffiti made it onto the annual ‘Ten Best’ lists of the

New York Times and

Time, while

Love Story, The Godfather, The Sting and

Rocky all made it onto the National Board of Review’s annual lists of the ten best English-language films, with

The Sting getting the award for best English-language film of the year.

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, The Godfather, Blazing Saddles and

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest all won screenplay awards from the Writers Guild of America, and the Directors Guild gave its director awards to

The Godfather,

The Sting,

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and

Rocky. Love Story, The Godfather, The Exorcist, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and

Rocky all won multiple Golden Globes, including those for Best Drama, while

American Graffiti won for Best Musical/Comedy.

Finally, between them, the Top 14 won numerous Oscars, in several years completely dominating the awards ceremony (see entries on individual films in Elley 2000). In 1969 Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid won four Oscars (including Best Screenplay) from seven nominations (including Best Picture and Director). The following year, Love Story won one award (Best Score) from seven nominations (including all five major categories: Best Picture, Director, Actor, Actress and Screenplay), while Airport had one win (Best Supporting Actress) from ten nominations (including Best Picture). Nominations in the Best Picture and Director categories indicate that the film in question was considered as a major artistic achievement by people working in the film industry, even if it did not win. However, it is, of course, the winning of these awards which most clearly signals to the world what Hollywood regards as its greatest films. In 1972, The Godfather won Best Picture, Actor and Screenplay from eleven nominations. The Sting ruled the 1973 ceremony, with seven wins (including Best Picture, Director and Screenplay) from ten nominations; only seven films in Hollywood history had ever received more Oscars (Steinberg 1980: 258). American Graffiti won nothing, but was nominated five times (including Best Picture, Director and Screenplay), while The Exorcist won Best Screenplay and Sound from ten nominations (including Best Picture and Director). In 1974, The Towering Inferno won three awards (Best Cinematography, Song and Editing) from eight nominations, which included Best Picture. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest swept the 1975 Academy Awards; nominated for ten Oscars, it won in all the five major categories, which had only happened once before in Academy history (It Happened One Night, 1934). While Jaws was nominated for Best Picture, it only won Best Sound, Score and Editing. Finally, with awards for Best Picture, Director and Editing (from ten nominations) Rocky was the main winner in 1976.

Again and again during the decade from 1967 to 1976 did the film industry publicly declare its biggest commercial hits to be amongst its greatest films, and in four out of ten years, the undisputed overall winners at the Academy Awards belonged to the Top 14. There is a remarkable consistency in the Academy Award performance of this group of films. Indeed, even the two films which were not recognised by the Academy with a Best Picture or Best Director nomination, were nominated in other categories:

Blazing Saddles received three nominations (without a win), while

The Poseidon Adventure had one win from eight nominations. When also considering the other awards mentioned above as well as the ‘Ten Best’ lists, readers’ surveys and critics’ polls from the late 1960s to the late 1970s, the amount of recognition the Top 14 received – as the best and/or the most significant and/or as favourites – is impressive indeed. This is yet another confirmation for the absolute centrality of the Top 14 in the film culture of their time.

Having established their centrality, we can now ask whether the New Hollywood Top 14 are a distinctive set of films. In other words, do these fourteen films have a lot in common with each other, and are they clearly distinguished from the big hits of earlier and later periods? The comparison with the biggest hits of the years since 1977 will have to wait until the conclusion. So what about the biggest hits before 1967?

The Roadshow Era Top 14, 1949–66

Thomas Schatz (1993), Sheldon Hall (2002) and Steve Neale (2003) have all offered succinct surveys of the biggest hits across American film history, concentrating on those films which were both unusally expensive and exceptionally successful at the box office. Since the 1950s, these films have commonly been known as ‘blockbusters’; indeed, during this decade Hollywood was gripped by a ‘blockbuster mentality’ (Hall 2002: 11; Neale 2003: 47; Schatz 1993: 12). From the 1910s to the 1940s, the American film industry very occasionally produced a film that left the competition far behind. Even when their numerous re-releases are discounted, both D. W. Griffith’s Civil War epic

The Birth of a Nation (1915) and Walt Disney’s animated feature

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) earned twice as much as their closest competitors in the decades before 1939 (Finler 2003: 356–7). Then, in 1939/40, David O. Selznick’s Civil War epic

Gone With the Wind, during the first of its many releases, multiplied the previous record. While this new record was not broken in the 1940s, the number of extremely high-grossing films increased dramatically. Comparisons across decades are notoriously difficult because of ticket price inflation, yet it is safe to say that the level of commercial success achieved so uniquely by

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs ($8m rentals) in the 1930s, became a still rare, but quite regular occurrence during the 1940s. Then, it pretty much became an annual event, beginning with Cecil B. DeMille’s biblical epic

Samson and Delilah in 1949.

There are further reasons for identifying 1949 as the starting point of a new era in American film history. To begin with, during the previous year, the unfavourable Supreme Court ruling in the so-called Paramount case, in which the major Hollywood studios had been accused of monopolistic practices, marked the definite end of an era. Most importantly, the ruling outlawed vertical integration, that is the combination of film production, distribution and exhibition within the same company, which had been the cornerstone of the Hollywood studio system since the 1920s. Without their American theatre chains (which gradually gained their independence in the late 1940s and early 1950s), the Hollywood majors had to find new ways of doing business. At the same time, they felt the effects of a spectacular decline in cinema attendance which had started in 1947. The average weekly attendance – which had been relatively stable for several years at record heights – plummeted from 82m in 1946 to 73m in 1947; thereafter the annual loss of about 10 per cent of the audience continued until in 1952 average weekly attendance was only 42m, that is about half the 1946 figure (Finler 2003: 378). After a temporary, slight recovery in the mid-1950s, attendance levels dropped further until, from 1966 onwards, they stabilised (with only minor fluctuations for the next two decades) at less than a quarter of the 1946 attendance (2003: 379). Throughout this period, foreign markets became ever more important, especially continental Europe, where cinema audiences were in fact growing across most of the 1950s (Hall 1999: vol. 1, 325–7; Krämer 2000: 197–8).

Television was not responsible for the initial audience decline in the US (because few people owned a set in the late 1940s when this decline set in), but it certainly was a major reason for the ongoing reduction in ticket sales. Television ownership increased from 9 per cent of all US households in 1950 to 93 per cent in 1966 (Finler 2003: 375). 1954 was the first year in which more than half of all households had TV, offering daily entertainment which included numerous, yet mostly minor films that had originally been made for, and shown in, movie theatres (see Lafferty 1990: 236–40). From 1955 onwards the number of theatrical movies on TV exploded, now including a wealth of important pre-1948 releases from the major studios (1990: 240–2). In 1961 movies, which had previously been shown mainly on independent local TV stations, became a staple of network programming; NBC’s

Saturday Night at the Movies included films made after 1948 and became a prime-time success, especially with young, urban viewers (1990: 245).

The Supreme Court ruling, the drop in attendance levels and the increasing availability of movies on television created a situation in which the major Hollywood studios began to make fewer, more expensive films and came to depend heavily on the blockbuster success of their main releases. Initially, in the late 1940s and early 1950s, in the wake of the much reduced production levels of the war years, the major studios increased their output, but after 1953 – partly because more old movies were becoming accessible to more people on television – the studios’ feature film output declined once again, never to recover (Finler 2003: 364). An industry which had previously revolved around mass production and habitual consumption (with one- to two-thirds of the population going to the cinema every week) now became hit driven, with major blockbuster success depending on a film’s ability to draw in the large majority of the American population who had stopped going to the cinema on a weekly basis (see Jowett 1976: 478). Such success also depended increasingly on a film’s ability to attract foreign audiences, especially in Europe, where cinemagoers tended to prefer European-themed Hollywood imports (often based on European source material, shot on European locations and featuring European stars) to more specifically American films (Garncarz 1994: 103–5; Krämer 2002a: 231–2).

As noted above, almost every year from 1949 onwards saw the release of one or more films which left the competition in the US (and also often in foreign markets) far behind (see

appendix 3). The breakaway success of

Samson and Delilah in 1949 (with $12m rentals) was followed by that of another Biblical epic,

Quo Vadis ($12m), in 1951. One year later, another Cecil B. DeMille spectacular, the circus drama

The Greatest Show on Earth earned $14m. Like

The Birth of a Nation,

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and

Gone With the Wind, these three films were roadshows, that is, they were first presented in only a few showcase theatres, where they had very long runs (often for years) at premium prices, usually with separate performances (unlike the usual practice of running films continuously across the day), advance bookings, orchestral overtures and intermissions. After a while, mostly while the original roadshow run was still going on, these films also received a general release at regular prices in regular cinemas. In various published and unpublished manuscripts, Sheldon Hall has explored the roadshow phenomenon across American film history (see, for example, Hall 1999 and 2002). He has noted that after the Second World War Hollywood invested more heavily than ever before in an increasing number of films intended for roadshow release, and that almost all of the big hits from 1949 to 1966 were roadshows. This period, then, can best be understood as the ‘Roadshow Era’. The Roadshow Era came into its own with the introduction of various spectacular widescreen formats in 1952/53.

This is Cinerama (1952), a travelogue introducing the most spectacular format (making use of three projectors and a massive curved screen), earned $15m, and the biblical epic

The Robe (1953), the first CinemaScope release, earned $18m. In subsequent years, both the number of movies earning $12m and more, and the earnings of the true breakaway hits increased, culminating with

The Sound of Music (1965) which generated $80m.

Due to ticket price inflation, figures across the Roadshow Era are not comparable. Average ticket prices rose from 38c in 1949 to $1.09 in 1966 and premium ticket prices for roadshow presentations also rose (Finler 2003: 378–9). If this inflation is taken into account, the Top 14 for this period are as follows (see

appendix 4):

| 1952 |

The Greatest Show on Earth (with non-adjusted rentals of $14m) |

| 1953 |

The Robe ($18m) |

| 1956 |

The Ten Commandments ($43m) and Around the World in Eighty Days ($23m) |

| 1957 |

The Bridge on the River Kwai ($17m) |

| 1959 |

Ben-Hur ($37m) |

| 1961 |

West Side Story ($20m) |

| 1963 |

Cleopatra ($26m) |

| 1964 |

My Fair Lady ($34m), Mary Poppins ($31m) and Goldfinger($23m) |

| 1965 |

The Sound of Music ($80m), Doctor Zhivago ($47m) and Thunderball ($29m) |

With the exception of

Mary Poppins and the two James Bond films,

Goldfinger and

Thunderball, these were all roadshows. For the purposes of calculating their market shares, I will assume that these films, which often ran for years, earned all rentals in their year of release (indeed, most films earned a fair share of their overall rentals during the early stages of their release). To determine approximate figures for box office grosses, I simply double the rental figures.

The Greatest Show on Earth has the smallest market share. Its $28m gross makes up just over 2 per cent of total revenues from ticket sales in 1952 ($1,246m), while all the other films have market shares over 3 per cent (Finler 2003: 376–7). The $160m gross of

The Sound of Music constitutes a staggering 17 per cent of the total revenues in 1965 ($927m). If we look across the fourteen years from 1952 to 1965, the total box office gross of the fourteen top hits (one per year) was $884m; this is 6 per cent of the total box office revenues during these years ($14,976m). This percentage is lower, but comparable to the one for 1967–76. Counting only the top ten films for the decade (again one per year), their total gross of $1,402m amounts to 10 per cent of the total income from ticket sales ($14,656).

It is difficult to determine how many tickets each of the roadshows sold, because prices during the initial roadshow release were well above the average ticket price, which only applied to the tickets sold when the film later went on general release. Let us therefore assume that, across the roadshow and regular releases, the ticket prices for these films were 50 per cent higher than the average ticket price in their year of release. Hence, we can estimate that The Greatest Show on Earth, with a $28m gross, sold 41m tickets for an average 69c (50 per cent more than the average ticket price of 46c in 1952) (Finler 2003: 378). This was the equivalent of 26 per cent of the American population in 1952 (157m) (Wattenberg 1976: 8). According to the same calculation, The Sound of Music sold 106m tickets during its first release, the equivalent of 55 per cent of the 1965 population (194m). Because Thunderball was not a roadshow, we can use the average ticket price for 1965 ($1.01), which means that the film sold almost 58m tickets, the equivalent of 30 per cent of the American population. While some of the above figures are only rough estimates, they do indicate that population percentages for Roadshow Era superhits are comparable to those calculated for the New Hollywood Top 14.

The tie-ins with best-selling soundtracks are also extensive. The following Roadshow Era Top 14 soundtracks were listed in

Billboard’s annual top ten (which started in 1957):

Around the World in Eighty Days (no. 4 in 1957 and no. 6 in 1958);

West Side Story (no. 1/1962, no. 1/1963, no. 4/1964);

Mary Poppins (no. 1/1965);

My Fair Lady (no. 4/1965);

The Sound of Music (no. 3/1965, no. 2/1966, no. 3/1967);

Doctor Zhivago (no. 7/1966 and no. 3/1967) (

People 2000: 223). Unlike the New Hollywood Top 14, many of the Roadshow Era superhits were adaptations of Broadway musicals, two of which –

My Fair Lady (running from 1956 to 1962) and

The Sound of Music (1959–63) – had been among the fifteen longest-running shows in Broadway history up to that point (

People 2000: 327). What is perhaps even more important is the success of the original cast albums for the Broadway shows:

My Fair Lady was no. 1 in 1957 and 1958 as well as no. 9 in 1959;

The Sound of Music was no. 1 in 1960, no. 4 in 1961 and no. 5 in 1962; the original cast album of

West Side Story joined the film soundtrack in the top ten of 1962 (at no. 2) (

People 2000: 223). Between them, original cast and soundtrack albums for the Top 14 of the Roadshow Era dominated album charts from 1957 to 1966, with a strong presence even in 1967.

The connection between the Top 14 and best-selling books was equally extensive. To begin with, three of the films told stories related to the biggest best-seller of all time, the Bible. Indeed, the Revised Standard Version of the Bible was the best-selling non-fiction hardcover of 1953 (the year

The Robe was released) and 1954 (

People 2000: 299). Also in 1953, Lloyd C. Douglas’ novel

The Robe was at the top of the fiction chart; the book had been in the top ten every year between 1942 and 1945, mostly in one of the two top spots, before the release of the film adaptation revived its sales. Only a few years before the release of

The Ten Commandments, books about Moses had been in the fiction and the non-fiction top ten. While Lew Wallace‘s

Ben-Hur (first published in 1880) did not re-appear in the charts in the 1950s, it had been one of the best-selling books in American publishing history up to that point (Mott 1947: 173–4, 261).

Doctor Zhivago, which had won the Nobel Prize for Boris Pasternak in 1958, had also been the best-selling fiction hardcover in that year, slipping to no. 2 in 1959.

Around the World in Eighty Days and

Mary Poppins were based on classic stories (by Jules Verne and P. L. Travers, respectively) and

The Bridge on the River Kwai on a recent book by Pierre Boulle. The two James Bond films were based on novels by best-selling author Ian Fleming, whose

You Only Live Twice was the eighth best-selling novel of 1964, while

The Man With the Golden Gun was at no. 7 in 1965. Over the years, most of Fleming’s books and also some of the other novels adapted into breakaway blockbuster movies during the Roadshow Era sold millions of copies; these books included

Thunderball (4.2m copies sold by 1975) and

Goldfinger (3.7m) as well as

Doctor Zhivago (5m),

The Robe (3.7m) and

The Bridge on the River Kwai (2m) (Hackett & Burke 1977: 11–19).

FIGURE 3 The Sound of Music (Robert Wise, 1965)

As the theatrical adaptations did with the Broadway shows and original cast albums, the literary adaptations drew on the often massive popularity of their source material, but they also, most likely, helped to sell millions of paperbacks. In any case, just like the New Hollywood Top 14, the Top 14 of the Roadshow Era resonated widely and deeply across American culture in the 1950s and 1960s. They also had a tremendous impact on subsequent film production and the success of future releases. The cycle of hugely successful Biblical epics, from

Samson and Delilah to

Ben-Hur, inspired filmmakers and studio executives to give a range of historical topics an epic treatment. This resulted in several cycles of historical epics, that is, films which set their stories of personal struggle and love against the spectacular backdrop of key moments in (mostly Western) history. These cycles included ancient epics like

Spartacus (the highest-grossing film of 1960) and

Cleopatra CLst/1963); medieval epics such as

El Cid (3rd/1961); nineteenth-century epics like

How the West Was Won CLst/1962) and

Hawaii (1st/1966); and twentieth-century epics including

Giant (3rd/1956),

Doctor Zhivago (2nd/1965) and

The Sand Pebbles (4th/1966) as well as epic Second World War films such as

From Here to Eternity (2nd/1953),

The Bridge on the River Kwai (1st/1957),

The Guns of Navarone (2nd/1961) and

The Longest Day (2nd/1962).

Historical epics in turn gave a boost to prestigious historical dramas – notably Tom Jones 3rd/1963) and A Man For All Seasons (5th/1966) – and to spectacular historical adventures, that is, films focusing on (often comic) action rather than the processes of historical change. These included 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (3rd/1954) and Around the World in Eighty Days (2nd/1956) as well as Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines (4th/1965) and The Great Race (5th/1965). The string of superhit musicals from West Side Story to The Sound of Music – which, in turn, had built on the success of earlier musicals from Jolson Sings Again (3rd/1949) to South Pacific (1st/1958) – also had a major impact on American film culture, which would be felt in the overproduction of big-budget musicals after 1966.

Thus, the Roadshow Era Top 14 helped to shape film production and hit patterns across the 1950s and 1960s. Finally, like the New Hollywood Top 14, they received widespread recognition from critics, from the Academy and in audience polls. Ten of the fourteen were included on the annual ‘Ten Best’ lists of the New York Times, three made it onto the Time lists between 1952 and 1961 (the list was not compiled from 1962 to 1966), and seven were ranked among the annual top ten of the National Board of Review (Steinberg 1980: 172–4, 176–8, 278–81).

Five of the fourteen were recognised as the Best Picture of the year by the Los Angeles Film Critics Association, and nine won Golden Globes for Best Drama or Best Musical/Comedy from the Hollywood Foreign Press Association (1980: 267–9, 288–93). When a representative sample of cinemagoers were asked about the best film they had seen in 1965, the resulting chart was headed by

The Sound of Music, followed by

Mary Poppins, Goldfinger,

Cleopatra and

My Fair Lady, Top 14 films which had been released in preceding years, but had extended runs across the decade (Anon. 1965a). A later survey of women found that their favourite films during 1966 were

The Sound of Music, Doctor Zhivago and

My Fair Lady (Anon. 1967a). In a readers’ survey conducted by the

Los Angeles Times in 1967, both

Ben-Hur and

Around the World in Eighty Days made it onto the list of their twenty all-time favourites (Steinberg 1980: 189).

In addition to their overwhelming recognition by both critics and audiences, the Roadshow Era Top 14 also dominated award ceremonies organised by the film industry itself. Four won screenplay awards from the Writers Guild of America and five won the director award from the Directors Guild (Steinberg 1980: 312–13, 318–19). Except for the two James Bond films, all of the Top 14 were nominated for Best Picture (as well as numerous other Oscars), and seven won this award (as well as numerous others) (see entries for each film in Elley 2000). In 1957, The Bridge on the River Kwai won a total of seven Oscars, including an almost clean sweep of the five major categories (not surprisingly, Best Actress was missing). In 1959 Ben-Hur won a record eleven Oscars, which was almost matched by the ten Oscars for West Side Story in 1961. My Fair Lady dominated the 1964 ceremony with eight wins and Mary Poppins won five that year, while, between them, The Sound of Music and Doctor Zhivago won ten Oscars in 1965.

Just like the New Hollywood Top 14 from 1967 to 1976, the Top 14 of the Roadshow Era dominated American film culture in every conceivable way between 1949 and 1966. While their level of dominance is the same, the two sets of films are very different.

The Top 14s in comparison

The distinctive characteristics of the New Hollywood Top 14 can best be observed after first establishing commonalities among the Roadshow Era Top 14. With the exception of

The Greatest Show on Earth, the films can easily be grouped into three broad categories: historical epics – both biblical (

The Robe, The Ten Commandments, Ben-Hur) and non-Biblical (

The Bridge on the River Kwai, Cleopatra, Doctor Zhivago), musicals – with both historical (

Mary Poppins, The Sound of Music) and contemporary (

West Side Story) settings, and international adventures – again both historical (

Around the World in Eighty Days) and contemporary (

Goldfinger and

Thunderball). What is more, the three categories are closely connected insofar as

The Sound of Music has an epic dimension, setting its central story against the rise of fascism. All of the epics and two of the three musicals have non-American settings, and apart from

The Bridge on the River Kwai none of these films feature any American characters, while their non-American protagonists are almost all played by foreigners, mostly British actors. This internationalism is shared by the international adventures, which take place mostly outside the US and feature only a few American supporting characters, with the non-American main characters again being played by British actors. (As suggested above, this internationalism helped many of these films to succeed in foreign markets.)

Another important feature of the Roadshow Era Top 14 is that, with the exception of Mary Poppins, Thunderball and Goldfinger, they were all roadshows. A roadshow release signalled the special status of the film, setting it apart from the kinds of films that people might attend habitually. Attendance at a roadshow had all the trappings of a rare, expensive and prestigious outing to a legitimate theatre, and even when the film went on general release some of this prestige and event status was likely to remain attached to it. The extraordinary length of these films (mostly between two and a half and four hours at a time when 90–100 minutes was still the norm), and their widely publicised, huge budgets confirmed that their makers had gone out of their way to offer audiences an overwhelming, in many ways unique experience (this also applies to Mary Poppins). An average release by one of the major studios cost about $1m to make in 1949 and $1.5m in the early 1960s (Steinberg 1980: 50), yet even a comparatively cheap roadshow like The Bridge on the River Kwai had a budget of $2.9m in 1957, while The Ten Commandments ($13m) and Cleopatra ($40m) broke all existing records (for budgets of these and other Top 14 films, see Finler 2003: 95, 123, 154, 190, 244, 269, 298, 331).

Given their budgets and roadshow presentation, the Roadshow Era superhits, except for the two Bond films, clearly were calculated block buster hits, that is, they were geared towards the largest possible audience and needed to reach it to make a profit (this is not to say that all such films are successful, as will be discussed in the next chapter). Despite potentially controversial elements (most notably eroticism and brutality) in some of the films, the roadshows and

Mary Poppins were basically addressed to an all-inclusive family audience. With the exception of

The Bridge on the River Kwai, these films also highlight elements which have traditionally been associated more with female than with male audiences: romance, familial love, sentimentality, lavish costumes and/or song and dance (more about this in the next chapter). Interestingly, several of these films gave first billing to their female leads and were clearly built around their performances: Betty Hutton in

The Greatest Show on Earth, Natalie Wood in

West Side Story, Elizabeth Taylor in

Cleopatra, Julie Andrews in

Mary Poppins and

The Sound of Music, and Audrey Hepburn in

My Fair Lady.In many ways, the two Bond films stand apart from the other twelve films in the Roadshow Era Top 14. They were not given roadshow releases, had lower (albeit still above average) budgets and foregrounded elements such as sex and violence that have traditionally been associated with male audiences, especially male youth, while at the same time being regarded as inappropriate for children. Whether children were actually kept away from Bond films in the mid-1960s and to what extent women disliked them is difficult to determine. Nevertheless, the two Bond superhits provide a transition to the blockbuster successes of the New Hollywood.

With the exception of

Airport, none of the New Hollywood Top 14 had a full-blown traditional roadshow presentation. Nevertheless, some of the Top 14 were given special releases, starting out in a small number of theatres, sometimes in a special format (70mm) and occasionally demanding premium ticket prices, before being released more widely. According to Sheldon Hall this applied, to a greater or lesser extent, to

The Godfather, The Poseidon Adventure, The Exorcist and

The Towering Inferno. These films had above-average budgets and length, but they did not match the extremes of the Roadshow Era Top 14, not even

The Towering Inferno, which ran for 165 minutes and cost $15m to make at a time when the average budget for a release from a major studio was $2.5m (Steinberg 1980: 50). The other nine films varied in length between less than 100 minutes (

Love Story, 99 mins;

Blazing Saddles, 93min) and just over two hours (

The Sting, 127 mins;

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, 133 mins), and also in cost, with

American Graffiti ($0.7m) and

Rocky ($1.5m) at the lower end – well below the average budget – and

Jaws ($12m) at the top end (Finler 2003: 95, 123, 154, 190, 244, 269, 298, 331). The big-budget special releases, the vehicles for top stars (such as Paul Newman and Robert Redford in both

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and

The Sting and Jack Nicholson in

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest) and the films based on huge best-sellers could reasonably have been expected to do well at the box office – they were calculated blockbusters – but

The Graduate,

American Graffiti,

Blazing Saddles and

Rocky were big surprises.

FIGURE 4 The Godfather (Francis Ford Coppola, 1971)

The presence of several surprise hits, then, is one of the distinctive features of the New Hollywood Top 14, prefigured, one might say, by the transitional Bond films – although these were sequels and therefore no longer a true surprise; the level of their success was, however, unexpected. Another distinctive feature is the absence of epics, musicals and international adventures from the New Hollywood Top 14. True, The Godfather is a historical drama with epic scope, but it does not deal directly with important developments in Western history, although it may be understood as an allegory thereof. While the roadshow epics depicted transformative events affecting whole societies and the course of subsequent history (the liberation of the Israelites and the delivery of the ten commandments, the fall of the Egyptian empire, the crucifixion of Christ and the beginnings of Christianity, the Russian Revolution and the Second World War), The Godfather portrays the development of a criminal organisation in the form of a family drama.

Of the four other films in the Top 14 with historical settings, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and Blazing Saddles deal with the disappearance of the Old West, yet they hardly do so with the seriousness and the excessive spectacular displays so characteristic of the epic (see Sobchak 1990). Set in 1962, American Graffiti also deals with the end of an era (the ‘fifties’), but this is only made explicit at the very end, when the onscreen text outlines the subsequent fate of the four male leads (one missing in action in Vietnam, another living in Canada, presumably to evade the draft). The Sting, finally, is tightly focused on friendships and enmities in the criminal world of 1930s America.

As to international adventures, it is noticeable that with the exception of The Poseidon Adventure, which is set on an oceanliner in international waters, the Top 14 are all set in the United States, with only a few scenes in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, The Godfather and The Exorcist venturing abroad. Finally, one might say that the musical tradition is still resonating in the New Hollywood Top 14, what with the importance of pop songs on the soundtracks especially of The Graduate and American Graffiti, but apart from a few scenes in Blazing Saddles and perhaps The Godfather, characters do not express themselves through song and dance.

If the New Hollywood Top 14, unlike the superhits of the Roadshow Era, are neither epics nor international adventures nor musicals, what are they? By and large, it is much more difficult to group them together. Most clearly related are the three disaster films. One might put

The Graduate and

Love Story together as romantic comedy-dramas (with the former mainly comedic, the latter mainly dramatic).

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, The Sting and

Blazing Saddles are buddy movies focusing on male friendship; one could stretch this category to include three other films centring on male partnerships or friendships (

The Godfather, Jaws and

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest). Or one might group together historical comedy-dramas (

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, The Sting, American Graffiti and

Blazing Saddles) and the closely related historical drama

The Godfather. Alternatively, one might use more established genre categories, describing

The Godfather as a gangster film and

The Sting perhaps as a gangster comedy;

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and

Blazing Saddles as westerns;

The Exorcist as a horror film and also perhaps

Jaws. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and

Rocky might both be described as contemporary dramas.

Obviously, the possibility to apply a multiplicity of labels to individual films is in the nature of popular cinema and not unique to the New Hollywood Top 14. Steve Neale has shown that the marketing and reception of any particular Hollywood film usually involves a range of generic terms rather than tying the film down to a single genre (2000: Ch. 7). However, the above discussion suggests that, in terms of generic labelling, the New Hollywood superhits are a much more diverse set than the Roadshow Era Top 14 (to follow up this suggestion it would be necessary to examine the generic terms used, for example, on posters and in reviews for these films). At the same time, it has to be noted that, while being generically diverse, the New Hollywood superhits are more restricted in terms of temporal and spatial settings than the ones from the Roadshow Era. The stories take place – primarily and in most cases exclusively – in the US during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, mostly in the 1960s and 1970s. By contrast, the settings of the Roadshow Era Top 14 range around the globe (quite literally in

Around the World in Eighty Days), with Egypt and Palestine, Rome and London, Russia and Austria featured prominently. The timeframe ranges from more than one thousand years BC to the 1960s. Only four films are set in contemporary times, only two primarily in the US, whereas the New Hollywood Top 14 are all, as we have seen, primarily set in the US, and only five are set in the past.

Another notable difference between the two sets of films is the dramatically increased prominence of potentially controversial elements in New Hollywood superhits. Compared to the very strict, traditional, often explicitly religious morality of most of the Roadshow Era Top 14 (with the exception of the Bond films and, possibly, The Bridge on the River Kwai), the largely sympathetic portrayals of criminals in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, The Godfather, The Sting and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest seem daring, as do the casual affairs (adulterous and otherwise) or one-off sexual encounters and occasional (near) nudity in several of the films (notably The Graduate, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, American Graffiti and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest). Similarly transgressive are the (comical) racial slurs and scenes of interracial sex in Blazing Saddles. Then there are scenes of intense and graphic violence in The Godfather (where the climactic massacre is presented explicitly as sacrilegious), The Exorcist (where the most shocking violence is sexualised as well as sacrilegious), Jaws (with its protracted killing at the beginning, its dismembered bodies and its climactic death of one of the protagonists who is half swallowed by a shark), One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (with its electric shock therapy, bloody suicide and climactic mercy killing) and Rocky (with its graphic boxing scenes). In the final scene of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid the violent death of the two protagonists in a hail of bullets is evoked through the sound of countless shots being fired, while the image is frozen on the precise moment before their bodies are hit.

Several of these films were widely perceived as being unsuitable for children. The clearest indication of this is their ratings.

The Godfather, The Exorcist and

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest all received an ‘R’, which meant that those under 17 could not attend without an adult. Only one of the New Hollywood Top 14 (

Airport) received a ‘G’ (suitable for general audiences).

The Graduate was released before the ratings system was introduced in 1968, but upon re-release it received a ‘PG’ (parental guidance suggested) like most of the others. When the Roadshow Era Top 14 received belated ratings, most of them, by contrast, had a ‘G’, that is, their status as family entertainment was confirmed. The others received ‘GP’ ratings, which were later retitled ‘PG’ (more about the meaning of these in

chapter two). These films were

Thunderball (rated in 1970),

Goldfinger (1971) and

Doctor Zhivago (1971);

The Bridge on the River Kwai received a ‘PG’ rating in 1991 (see the MPAA website,

http://www.mpaa.org/movieratings).

It is also reasonable to assume that many of the New Hollywood Top 14 appealed to males more than to females. The stories of all Top 14 films revolve around the experiences, desires and actions of men. Male bonding, sometimes combined with intense male rivalry and conflict, is central to many of the films. Close male relationships are at the centre of The Sting, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, The Godfather, American Graffiti, Blazing Saddles, Jaws and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest; to a lesser extent this also applies to The Exorcist and The Towering Inferno. In many cases, women are marginalised to the point where they disappear altogether, as in the final part of Jaws, in long stretches of The Godfather and The Sting as well as much of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. In The Exorcist the focus shifts dramatically from a mother and her daughter to a battle between a male-identified demon and two priests. American Graffiti deals with romantic relationships as well as with male friendships, but the women are dropped from the final titles outlining the future lives of the protagonists. In only three of the films does a woman receive top billing (Anne Bancroft in The Graduate, Ali McGraw in Love Story and Ellen Burstyn in The Exorcist). Romantic love is central only to a few of the films, notably The Graduate and Love Story, but even these two films – like all of the Top 14 – focus primarily on male protagonists. Where male/female relationships are foregrounded, they are characterised by seemingly unresolvable problems. At the end of The Graduate, the re-united couple is facing an uncertain future with somewhat blank or puzzled looks on their faces. At the end of Love Story, the protagonist’s wife is dead. In One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest the institution the hero rebels against is personified by a woman, who destroys him in the end. At the conclusion of Rocky, the proud, but defeated protagonist cries out for the woman he loves, but this privileging of romance takes place in the hyper-masculine setting of the boxing arena. On all levels, then, women are sidelined (or vilified) on screen and also therefore, one may assume, in the audience (although there is no doubt the sex appeal of male stars such as Paul Newman and Robert Redford and also the possibility that women make an emotional investment in male/male relationships; see Jenkins 1992: ch. 6).

Possibly connected to this gender bias is the emphasis of several of the New Hollywood Top 14 on organisational structures and professional activities.

Airport explores the complex operations of an airport and the particular skills needed by managers, pilots and technicians.

The Towering Inferno examines irresponsible building practices employed by large corporations and features firefighters as well as architects.

Jaws focuses on a policeman, a scientist and a fisherman and includes a lot of details on the responsibilities and limitations of police work, the biology and behaviour of sharks as well as the mechanics of shark hunting.

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest examines the operations of a mental institution, prominently featuring nurses and their varied day-to-day activities.

The Exorcist presents, in often excruciating detail, both the failure of medicine to treat the young protagonist, and then the success of the exorcism systematically executed by two priests (who are authorised by the Catholic Church).

The Godfather is almost wholly concerned with the portrayal of a complex criminal organisation, its hierarchies and strategies, its internal and external rivalries.

Rocky offers insights into the boxing world, depicting training regimes and fights as well as behind-the-scenes machinations. An interesting variation on this procedural emphasis is offered by

The Sting, in which con-artists set up an intricate organisation so as to take revenge for one of their own. While such procedural elements were already present in the Roadshow Era Top 14, especially

The Greatest Show on Earth, The Bridge on the River Kwai and the James Bond films, they came to dominate many of the New Hollywood Top 14.

Another important difference between the two sets of films is the shift (prefigured by West Side Story) from the presence of numerous nationalities in the Roadshow Era to a focus on American ethnicities and race relations in the New Hollywood. The Egyptians, Romans, Israelites, Russians, Austrians and Brits of the Roadshow Era Top 14 give way to hyphenated Americans. Most notably, Italian-American characters are at the centre of Love Story, The Godfather and Rocky, and there are the priest’s immigrant mother and a Jewish policeman in The Exorcist, a Native American in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, and an old Jewish couple in The Poseidon Adventure. The protagonist of Blazing Saddles is black as are supporting characters in several of the other films, most notably the antagonist in Rocky. Finally, while not cast as Jewish characters in the Top 14, Dustin Hoffman, Gene Wilder (in Blazing Saddles) and Richard Dreyfuss (in both American Graffiti and Jaws) may have carried over a sense of Jewishness from other roles and from their off-screen publicity.

Finally, it is worth pointing out that through foregrounding both procedural elements and ethnicities, the New Hollywood Top 14 explore social divisions and group conflicts in American society, thus situating the localised personal conflicts they portray in a wider context. This is also achieved through an emphasis on class differences (for example between the lovers in

Love Story and between the three protagonists of

Jaws) and on generational differences (with, for example, young people rebelling against their parents in

The Graduate and

Love Story and, fantastically, in

The Exorcist, while in

The Godfather a young man first tries to leave the family business behind, but then takes over his father’s role as the head of that business). While such social tensions are central to some of the Roadshow Era Top 14 (notably, around ethnicity in

West Side Story and class in

My Fair Lady), in the superhits of the earlier era conflicts within one society tend to be subordinated to international conflict or they are safely distanced by being located abroad and/or in the past (

West Side Story being the exception, while the circus setting in

The Greatest Show on Earth is presented as an international enclave within the US). By comparison, then, the New Hollywood Top 14 tell stories about deep divisions in American society, between institutions, professions, ethnicities, races, classes and generations. If the battle between the sexes is played down, it is because women are generally sidelined in these films.

Conclusion

American cinema of the years 1967–76, like that of the preceding era (1949–66), was dominated by a small group of films, which generated a significant portion of overall film industry income, were seen by up to half of the American population, had a mutually beneficial link to other best-selling cultural products (notably books and soundtracks), received widespread critical acclaim, were recognised by industry personnel as masterpieces and influenced future film production and hit patterns. As a group, the fourteen biggest hits of the New Hollywood contrasted in important ways with the fourteen superhits of the Roadshow Era. They included fewer special high-profile releases and more surprise hits than the earlier group of films, were generically more diversified but at the same time much more focused on contemporary American settings, dealt with American ethnicities rather than foreign nationalities and often explored organisations and professions as well as social divisions, in general were addressed more to men than to women and in some cases left the ideal of all-inclusive family entertainment far behind, mainly due to their prominent and graphic displays of sex and violence. The next chapter begins to explain how this dramatic shift came about.