![]()

Chapter 7: Basic Cost Control For Restaurants

This chapter will introduce you to the basic cost control concepts that will be developed in detail throughout the rest of this book. This chapter is being introduced now so that prior to developing the menu and menu items you can start to visualize the entire control process.

COST CONTROLS ARE CRUCIAL

Throughout the entire food-service industry, operating expenses are up and income is down. After taxes and expenses, restaurants that make money, according to the National Restaurant Association, have bottom lines at 0.5–3.0 percent of sales. This tiny percentage is the difference between being profitable and going under and it drives home the importance of controlling your costs.

A lot can be done to control costs and it begins with planning. Cost control is about numbers. It is about collecting, organizing, interpreting, and comparing the numbers that impact your bottom line. This job cannot be delegated because these numbers are your controls. They are what tell you the real story of what is going on in your restaurant. Some operators may need outside assistance in interpreting these numbers such as an accountant or food service consultant.

Understanding this story and its implications on your bottom line comes only with constant review and the resulting familiarity with the relationships between these numbers and the workings of the business. This story may seem like drudgery, but it is your key to understanding the meaning behind your numbers. Once you have mastered the numbers they will tell you the story behind your labor productivity, portion control, purchase prices, marketing promotions, new menu items, and competitive strategy. This knowledge will free you to run the most profitable operation you can.

According to government statistics, a restaurant investor has a one in 20 chance of getting his money back in five years. Furthermore, the consensus of many successful restaurateurs is that 80 percent of the success of a restaurant is determined before it opens. You must prepare. Part of that preparation is integrating an ongoing cost control program into your business.

This program can be doubly important if you are fortunate enough to start out doing great business. High profits can hide many inefficiencies that will surely expose themselves during times of low sales. Too many people become cost-control converts only after suffering losses. The primary purpose of cost controls is to maximize profits, not minimize losses. Controlling costs works — all the time — because it focuses on getting the most value from the least cost in every aspect of your operation. By keeping costs under control you can charge less than the competition or make more money from charging the same price.

These are huge operating freedoms and opportunities that are afforded you if you know what you are spending and control that spending. Most of the waste that occurs in restaurants cannot be detected by the naked eye. It takes records and reports to tell you the size of the inefficiencies taking place.

Cost control is not accounting or bookkeeping: These are the information-gathering tools of cost control. Cost control can be defined by explaining its purposes:

• To provide management with information needed for making day-to-day operations decisions.

• To monitor department and individual efficiency.

• To inform management of expenses being incurred and incomes received and whether they fall within standards and budgets.

• To prevent fraud and theft.

• To provide the ground for the business’s goals (not for discovering where it has been).

• To emphasize prevention, not correction.

• To maximize profits, not minimize losses.

This idea of prevention versus correction is fundamental. Prevention occurs through advanced planning. Your primary job is not to put out fires, it is to prevent them — and to maximize profits in the process.

The larger the distance between an owner or manager and the actual restaurant, the greater the need for effective cost control records. Cost control is how franchisers keep their eyes on thousands of units across the world. Many managers of individual operations assume that since they are on the premises during operating hours, a detailed system of cost control is unnecessary. Tiny family operations often see controls the same way and view any device for theft prevention as a sign of distrust towards their staff. The main purpose of cost control is to provide information to management about daily operations. Prevention of theft is a secondary function. Cost controls are about knowing where you are going. Most waste and inefficiencies cannot be seen; they need to be understood through the numbers.

Understanding those numbers means interpreting them. To do this effectively you need to understand the difference between control and reduction. Control is achieved through the assembly and interpretation of data and ratios on your revenue and expenses.

Reduction is the actual action taken to bring costs within your predetermined standards. Effective cost control starts at the top of an organization. Management must establish, support, and enforce its standards and procedures.

There are ten primary areas that are central to any food and beverage operation and are therefore crucial elements of cost control records:

• Purchasing. Your inventory system is the critical component of purchasing. Before placing an order with a supplier you need to know what you have on hand and how much will be used. Allow for a cushion of inventory so you do not run out between deliveries. Once purchasing has been standardized, the manager simply orders from your suppliers. Records show supplier, prices, unit of purchase, and product specifications. This information needs to be kept on paper.

• Receiving. Receiving is how you verify that everything you ordered has arrived. Check for correct brands, grades, varieties, quantities, and correct prices. Incorrect receivables need to be noted and either returned or credited to your account. Products purchased by weight or count need to be checked.

• Storage. All food is stored until it is used. Doing so in an orderly fashion ensures easy inventory. Doing so properly, with regard to temperature, ventilation, and freedom from contamination, ensures food products remain in optimum condition until they are used. Expensive items need to be guarded from theft.

• Issuing. Procedures for removing inventory from storage are part of the cost control process. Head chefs and bartenders have authority to take or “issue” stock from storage to the appropriate place. To know your food and beverage costs you need to know a) your beginning inventory, b) how much was sold, and c) your ending inventory. Without this data you cannot determine accurate sales figures.

• Rough preparation. How your staff minimizes waste during the preliminary processing of inventory is critical.

• Preparation for service. Roughly prepared ingredients are finished off prior to plating. The quality and care with which preparation is done determines the amount of waste generated in preparation of standard recipes.

• Portioning/Transfer. Food can be lost through over portioning. Final preparation should be monitored regularly to ensure quality and quantity standards are being adhered to. Portioning is such a crucial element to cost control that management must be assigned to monitor order times, portions, presentation, and food quality with an eagle eye.

• Order taking/Guest check. Every item sold or issued from the kitchen needs to be recorded by paper check or computer. It needs to be impossible for anyone to get food or drinks without having them entered into the system. No verbal orders for food or beverages should be accepted by or from anybody — including management and owners.

• Cash receipts. Monitoring sales is crucial to cost controls. Under-/overcharging, falsification of tips, and lost checks must be investigated after every shift. Sales information from each meal period must be compiled to build a historical financial record. This record helps you forecast the future.

• Bank deposits/Accounts payable. Proper auditing of bank deposits and charge slips must be conducted.

Cost control is an ongoing process that must be part of the basic moment-to-moment breathing of your business. A continuous appraisal of this process is equally integral to the functioning of your restaurant. There are five key elements to an effective cost control strategy:

1. Planning in advance.

2. Procedures and devices that aid the control process.

3. Implementation of your cost control program.

4. Employee compliance.

5. Management’s ongoing enforcement and reassessment.

Furthermore, your program should be assessed with the following questions:

1. Do your cost controls provide relevant information?

2. Is the information timely?

3. Is it easily assembled, organized, and interpreted?

4. Are the benefits and savings greater than the cost of the controls?

This last point is especially important. When the expense of the controls exceeds the savings, that is waste, not control. Spending $30,000 on a computer system that will save you $5,000 in waste is ineffective.

Standards are key to any cost control program. Predetermined points of comparison must be set, against which you will measure your actual results. The difference between planned resources and resources actually used is the variance. Management can then monitor for negative or positive variances between standards and actual performance and will know where specifically to make corrections. These five steps illustrate the uses of standards:

1. Performance standards should be established for all individuals and departments.

2. Individuals must see it as the responsibility of each to prevent waste and inefficiency.

3. Adherence — or lack of adherence — to standards must be monitored.

4. Actual performance must be compared against established standards.

5. When deviations from standards are discovered, appropriate action must be taken.

Your job is to make sure standards are adhered to. Is your staff using measuring scoops and ladles and sized bowls, glasses, and cups, weighing portions individually, portioning by count, and pre-portioning? These are all useful tools to make sure standards are met and your cost control program implemented effectively.

COST RATIOS

Owners and managers need to be on the same page in terms of the meaning and calculation of the many ratios used to analyze food, beverage, and labor costs. It is important to understand how your ratios are being calculated, so you can get a true indication of the cost or profit activity in your restaurant. Numerous cost control software programs are available with built-in formulas for calculating ratios and percentages. The Uniform System of Accounts for Restaurants (USAR), published by the National Restaurant Association, is an essential guide for restaurant accounting. It establishes a common industry language that allows you to compare ratios and percentages across industry lines. The goal of this comparison is to create financial statements that are management tools, not just IRS reports. Cost control is not just the calculation of these numbers. It is the interpretation of them and the appropriate (re)actions taken to bring your numbers within set standards.

FOOD COST PERCENTAGE

This basic ratio is often misinterpreted because it can be calculated so many ways. It is food cost divided by food sales. Whether your food cost is determined by food sold or consumed is a crucial difference. For your food cost percentage to be accurate, a month-end inventory must be taken. Without this figure your food cost statement is inaccurate and therefore useless. Your inventory will vary month to month — even in the most stable environment — because months end on different days of the week.

Distinguishing between food sold and consumed is important because all food consumed is not sold. Food consumed includes all food used, sold, wasted, stolen, or given away to customers and employees. Food not sold is determined by subtracting all food bought at full price from the total food consumed.

Maximum allowable food cost percentage (MFC) is the most food can cost and still return your profit goal. If, at the end of the month, your food cost percentage is over your maximum allowable percentage, you will not meet your profit expectations. Below is how you calculate MFC:

1. Write your dollar amounts of labor costs and overhead expenses and exclude food costs. Refer to past accounting periods and yearly averages to get realistic cost estimates.

2. Add your monthly profit goal as either a dollar amount or a percentage of sales.

3. Convert dollar values of expenses to percentages by dividing by food sales for the periods used for expenses. Generally, do not use your highest or lowest sales figures for calculating your operating expenses. Subtract the total of the percentages from 100 percent. The remainder is your maximum allowable food cost percentage (MFC). For example: 100 – [Monthly Expenses (– Food Costs) + Profit Goal x 100] = % MFC Monthly Food Sales

Actual food cost percentage (AFC) is the percentage you are actually operating at. It is calculated by dividing food cost by food sales. If you are deducting employee meals from your income statement, then you are calculating cost of food sold. If there is no deduction of employee meals — which is true for most operations — then the food cost you are reading is food consumed. Food consumed is always a higher cost than food sold and, if inventory is not being taken, the food cost on your income statement is just an estimate based on purchases and is not accurate.

Potential food cost percentage (PFC) is also called your theoretical food cost. PFC is the lowest your food cost can be because it assumes that all food consumed is sold and that there is no waste whatsoever. It is found by multiplying the number sold of each menu item by the ideal recipe cost.

Standard food cost (SFC) is how you adjust for the unrealistically low PFC. This percentage includes unavoidable waste, employee meals, etc. This food cost percentage is compared to the AFC and is the standard management must meet.

Prime food cost includes the cost of direct labor with the food cost. Prime food cost is labor incurred because the item is made from scratch — baking pies and bread, trimming steaks. When the food cost is determined for these items, the cost of the labor needed to prepare them is added. So prime cost is food cost plus necessary direct labor. This costing method is applied to every menu item needing extensive direct labor before it is served to the customer. Indirect labor cannot be attributed to any particular menu item and is therefore overhead. Prime cost is the total cost of food and beverages sold, payroll, and employee benefits costs.

Beverage cost ratio is calculated when alcoholic beverages are sold. It is determined by dividing costs by sales — calculated the same way as food consumed. A single beverage ratio cannot be standardized because the percentage will vary depending on the mix of hard alcohol, wine, and beer. Spirits run a lower cost percentage than wine and beer and, as such, it is recommended that alcoholic beverages be split into their three categories. Beverage sales do not include coffee, tea, milk, or juice, which are usually considered food. Wherever you include soft drinks, know that it will reduce the food cost, since the ratio of cost to selling price is so low.

Check average is not just total food and beverage sales divided by customers served. It is important to see how this figure compares to the check average you need to meet your daily sales goals. If you are coming in under what you need, you should look at your prices. Check average should be determined by each meal period, especially when different menus are served for each meal. Standards need to be set on how customers who order only a drink and no food are counted.

Seat turnover is how many times you can fill a chair during a meal period with another customer. Restaurants with low check averages need high seat turnover. Inventory turnover is calculated by dividing cost of food consumed by your average inventory (beginning inventory plus your ending inventory, divided by two).

Ratio of food to beverage sales is the ratio of their percentages of your total sales. In restaurants with a higher percentage of beverage sales than food sales, profits are generally higher because there is a greater profit margin on beverages.

Sales mix is the number of each menu item sold. Sales mix is crucial to cost analysis because each item impacts food cost differently. If your Wendy’s does a huge breakfast business and the one down the street does a big lunch, your food costs are going to be different than theirs.

Break-even point (BEP) is simply when sales equal expenses, period. Businesses can operate forever at breakeven if there are no investors looking for a return on their money.

Contribution margin is your gross profit. It is what remains after all expenses have been subtracted from 100 percent net.

Closing point is when the cost of being open for a given time period is more expensive than revenue earned. If it cost you $2,000 to open today, and you only made $1,800, your closing point expense will be $200.

CONTROLLING FOOD COSTS

In order to control food costs effectively, there are four things you need to do:

1. Forecast how much and what you are going to sell.

2. Purchase and prepare according to these forecasts.

3 Portion effectively.

4. Control waste and theft.

To do these effectively, you must have standards to which you rigorously adhere. Here are two main standards that will help you sustain quality, consistency, and low cost:

• Standardized recipes. Since the recipe is the basis for determining the cost of a menu item, standard recipes will assure consistent quality and cost. Standardized recipes include ingredients, preparation methods, yield, equipment used, and plate presentation.

• Standardized purchase specifications. These are detailed descriptions of the ingredients used in your standardized recipes. Quality and price of all ingredients are known and agreed upon before purchases are made, making the recipe’s cost consistent from unit to unit and week to week.

YIELD COSTS

Once you have standardized recipes in place, you can determine the per plate cost of every dish. You need to know what the basic ingredients cost and the edible yield of those ingredients for each dish. There are a number of necessary terms for this process:

• As-Purchased (AP) Weight. The weight of the product as delivered, including bones and trim.

• Edible Portion (EP) Weight. The amount of weight or volume that is available to be portioned after carving or cooking.

• Waste. The amount of usable product that is lost due to processing, cooking, or portioning, as well as usable by-products that have no salable value.

• Usable Trim. Processing by-products that can be sold as other menu items. These recover a portion or all of their cost.

• Yield. The net weight or volume of food after processing but before portioning.

• Standard Yield. The yield generated by standardized recipes and portioning procedures—how much usable product there is after processing and cooking.

• Standard Portion. The size of the portion according to the standardized recipe and also the basis for determining the cost of the plated portion.

• Convenience Foods. Items where at least a portion of the preparation labor is done before delivery. These can include precut chicken or ready-made dough.

These factors allow you to calculate plate costs. The food cost of convenience foods is higher than if you made them from scratch, but once you factor in labor, necessary equipment, inventories of ingredients, more complicated purchasing and storage, you may find that these foods offer considerable savings.

To cost convenience foods you simply count, weigh, or measure the portion size and determine how many portions there are. Then divide the number of servable portions into the as-purchased price. Even with their pre-preparation, a small allowance for normal waste must be factored in, often as little as 2 percent per yield.

Costing items from scratch is a little more complex. Most menu items require processing that causes shrinkage of some kind. As a result, if the weight or volume of the cooked product is less than the as-purchased (AP) weight, the edible portion (EP) cost will be higher than the AP price. It is a simple addition of the labor involved and the amount of saleable product being reduced. Through this process, your buyer uses yields to determine quantities to purchase and your chef discovers optimum quantities to order that result in the highest yield and the least waste.

MENU SALES MIX

The menu is where you begin to design a restaurant. If you have a specific menu idea, your restaurant’s location must be carefully planned to ensure customer traffic will support your concept. If you already have the location, design your menu around the customers you want to attract.

Once your concept is decided, your equipment and kitchen space requirements should be designed around the recipes on your menu. Once a kitchen has been built, there is of course some flexibility to menu changes, but new pieces of equipment may be impossible to add without high costs or renovations. To design right, you need to visualize delivery, processing, preparation, presentation, and washing. To do so you must be intimately familiar with each menu item.

When shopping for equipment, choose based on the best equipment for your needs, not price. Decide if you need a small fryer or an industrial one, two ovens or five, and then which specific brands meet your needs. Decide what pots, pans, dishes, and utensils you like before you begin to find the best price.

THE MENU ITSELF

Your menu should not just be a list of the dishes you sell; it should positively affect the revenue and operational efficiency of your restaurant. Start by selecting dishes that reflect your customer’s preferences and emphasize what your staff does well. Attempting to cater to everyone generally has you doing nothing particularly well and does not distinguish your restaurant. Your menu should be a major communicator of the concept and personality of your restaurant, as well as an important cost control.

A well-designed menu creates an accurate image of the restaurant in a customer’s head, even before she has been inside. It also directs her attention to certain selections and increases the chances of them being ordered. Your menu also determines, depending upon its complexity and sophistication, how detailed your cost control system needs to be.

An effective menu does five key things:

1. Emphasizes what customers want and what you do best.

2. Is an effective communication, merchandising, and cost control tool.

3. Obtains the necessary check average for sales and profits.

4. Uses staff and equipment efficiently.

5. Makes forecasting sales more consistent and accurate for purchasing, preparation, and scheduling.

The design of your menu will directly affect whether or not it achieves these goals. Plan to have a menu that works for you. Certain practices can influence the choices your guests make. Instead of randomly placing items on the menu, single out and emphasize the items you want to sell. These will generally be dishes with low food cost and high profits that are easy to prepare. Once you have chosen these dishes, use design — print style, paper color, and graphic design — to direct the reader’s attention to these items. In general, a customer’s eye will fall to the middle of the page first. Design elements used to draw a reader’s eye to another part of the menu can be effective as well. Customers remember the first and last things they read more than anything else, so drawing their eyes to specific items is also important.

Once you have an effective menu design, analyzing your sales mix to determine the impact each item has on sales, costs, and profits is an important practice. If you have costs and waste under control, looking at your menu sales mix can help you further reduce costs and boost profits. You will find that some items need to be promoted more aggressively, while others need to be dropped altogether. Classifying your menu items is necessary for making those decisions. Here are some suggested classifications:

• Primes. These are popular items that are low in food cost and high in profit. Have them stand out on your menu.

• Standards. Items with high food costs and high profit margins. You can possibly raise the price on this item and push it as a signature.

• Sleepers. Slow selling low food cost items with low profit margins. Work to increase the likelihood that these will be seen and ordered through more prominent menu display, featuring on menu boards, and lowered prices.

• Problems. High in food cost and low in profits. If you can, raise the price and lower production cost. If you cannot, hide them on the menu. If sales do not pick up, get rid of them altogether.

PRICING

Pricing is an important aspect of your revenues and customer counts. Prices that are too high will drive customers away and prices that are too low will kill your profits. But pricing is not the simple matter of an appropriate markup over cost; it combines other factors as well.

Price can either be market driven or demand driven. Market-driven prices must be responsive to your competitor’s prices. Common dishes that you and the place down the road sell or new menu items that have not met a demand need to be priced competitively. Opposite to these are demand-driven items, which customers ask for and where demand exceeds your supply. You have a short-term monopoly on these items and therefore price is driven up until demand slows or competitors begin to sell similar items.

However you determine your price, the actual marking up of items is an interesting process. A combination of methods is usually a good idea, since each menu item is different. Two basic theories are: a) charge as much as you can and b) charge as little as you can. Each has its pluses and minuses. Obviously, if you charge as much as you can, you increase the chance of greater profits. Charging the lowest price you can gives customers a great sense of value but lowers your profit margin per item.

Prices are generally determined by competition and demand. Your prices must be in line with the category customers put you in. Burrito joints do not price like a five-star restaurant and vice versa. Both would lose their customer base if they did. You want your customers to know your image and that your prices fit into that picture.

Here are four ways to determine prices:

1. Competitive pricing. Simply based on meeting or beating your competition’s prices, which is an ineffective method, since it assumes diners are making their choice on price alone, and not food quality, ambiance, or service.

2. Intuitive pricing. With this method, you do not want to take the time to find out what your competition is charging, so you are charging based on what you feel guests are willing to pay. If your sense of the value of your product is good, then it works. Otherwise, it can be problematic.

3. Psychological pricing. Price is more of a factor to lower-income customers who go to lower priced restaurants. If they do not know an item is good, they assume it is if it is expensive. If you change your prices, remember the order in which buyers see them also affects their perceptions. If an item was initially more expensive, it will be viewed as a bargain and vice versa.

4. Trial-and-error pricing. Based on customer reactions to prices. It is not practical in terms of determining your overall prices, but can be effective with individual items to bring them closer to the price a customer is willing to pay or to distinguish them from similar menu items with a higher or lower food cost.

There are still other factors that help determine prices. Whether customers view you as a leader or a follower can make a big difference on how they view your prices. If people think of you as the best seafood restaurant in the area, they will pay a little more to eat with you. Service also determines people’s sense of value when the difference in actual food quality between you and the competition is negligible. If your customers order at a counter and bus their own tables, this lack of service cost needs to be reflected in your prices. Also, in a competitive market, providing great service can be a factor that puts you in a leadership position and allows you to charge a higher price. Your location, ambience, customer base, product presentation, and desired check average all factor into what you feel you can charge and what you need to charge in order to make a profit.

FINANCIAL ANALYSIS

To make profits, you need to plan for profits. Many restaurants offering great food, atmosphere, and service still go out of business. They fail to manage the financial aspects of the business. Poor cost control management will be fatal to your business. Good financial management is about interpreting financial statements and reports, not simply preparing them.

A few distinctions need to be made in order to understand the language now being used. Financial accounting is for external groups to assess taxes and the status of your establishment. Managerial accounting provides information to internal users that becomes the basis for managing day-to-day operations. This data is very specific, emphasizes departmental operations, and uses non-financial data like customer counts, menu sales mix, and labor hours. These internal reports break down revenues and expenses by department, day, and meal period so they can be easily interpreted, exposing areas that need attention. Daily and weekly reports must be made and analyzed in order to determine emerging trends.

INTERNAL CONTROLS

It is estimated that about five cents on every dollar spent in U.S. restaurants is lost to theft. Clearly established and followed controls can lessen this percentage. Begin by separating duties and recording every transaction. If these basic systems are in place, then workers know that each step of the way they will be held responsible for shrinkage.

Management Information Systems (MISs) are common tools for accumulating, analyzing, and reporting data. They help establish proper rules for consistent and prompt reporting and set up efficient flows of paperwork and data collection. In short, their goal is to prevent fraud on all levels. Although no system is perfect, a good MIS will show where fraud or loss is occurring, allowing you to remedy the situation.

In most restaurants the majority of theft occurs at the bar. In tightly run establishments cash is more likely to be taken by management than hourly workers because managers and some wait staff as well as bartenders have access to it and know the system well.

Hourly workers tend to steal products, not cash, because that is what they can get their hands on. Keeping food away from the back door and notifying your employees when you are aware of theft and are investigating can have a deterring effect.

The key to statistical control is entering transactions into the system, electronically or by hand. If food or beverages can be consumed without being entered into the system, your system is flawed and control is compromised. Five other cost control concepts are crucial to your control system:

1. Documentation of tasks, activities, and transactions must be required.

2 Supervision and review of employees by management intimately familiar with set performance standards.

3. Splitting of duties so no single person is involved in all parts of the task cycle.

4. Timeliness. All tasks must be done within set time guidelines, comparisons then made at established control points, and reports made at scheduled times to detect problems.

5. Cost-benefit relationships. Cost of procedures used to benefits gained must exceed the cost of implementing the controls.

The basic control procedure is an independent verification at a control point during and after the completion of a task. Often done through written or electronic reports. This verification determines if the person performing the task has the authority to do so and if the quantity of product or cash and performance results meet set standards.

Point-of-sale systems are also crucial for reducing loss. If your servers simply cannot obtain any food or beverage without a hard-copy check or without entering the sale electronically, you have eliminated most of their opportunity to steal. Many electronic systems are available in the industry and once initial training and intimidation are overcome, they can seriously reduce the amount of theft and shrinkage in your restaurant.

These systems also allow you to instantly see which items are selling best at different times of the day, enabling you to order more efficiently and keep inventory to a minimum. They also allow you to automatically subtract from inventory all the ingredients used in the items you sold. These can be invaluable tools for tracking employee productivity, initiating promotions and contests, and generating weekly, daily, by-meal, or hourly sales reports. Point-of-sale systems collect invaluable data for you to interpret.

PURCHASING AND ORDERING

What exactly is the difference? Purchasing is setting the policy on which suppliers, brands, grades, and varieties of products will be ordered. These are your standardized purchase specifications; the specifics of how items are delivered, paid for, and returned are negotiated between management and distributors. Purchasing is what you order and from whom. Ordering is the act of contacting the suppliers and notifying them of the quantity you require, a simpler, lower-level task.

Once menus have been created that meet your customers’ satisfaction and your profit needs, a purchasing program designed to assure your profit margins can be developed. An efficient purchasing program incorporates:

• Standard purchase specifications; based on

• Standardized recipes; resulting in

• Standardized yields; that, with portion control, allow for

• Accurate costs based on portions actually served.

Once these criteria are met, to order the necessary supplies, your operator needs to be able to predict how much will be needed to maintain purchase specifications, follow standard recipes, and enforce portioning standards. When these are done well, optimum quantities can be kept on hand.

Buying also has its own distinctions. Open, or informal, buying is face-to-face or by over-the-phone contact and uses largely oral negotiations and purchase specifics. Formal buying terms are put in writing and payment invoices are stated as conditions for price quotes and customer-service commitments. Its customer service is possibly the most important aspect of the supplier you choose because good sales representatives know their products, have an understanding of your needs, and offer helpful suggestions.

INVENTORY

Ordering effectively is impossible unless you know your inventory. Before an order is placed, counts of stock should be made. Many software programs are able to determine order quantities directly from sales reports, but without this kind of system you must inventory what you have on hand before ordering. The taking of inventory must be streamlined because it must be done as frequently as you order. It must not be an unpleasant, late-night debacle that is done only rarely and only when it has to be. Whether your inventory system is by hand or computer, its purpose is to accomplish the following:

• Provide records of what you need.

• Provide records of product specifications.

• Provide records of suppliers.

• Provide records of prices and unit of purchase.

• Provide a record of product use levels.

• Facilitate efficient ordering.

• Increase the accuracy of inventory.

• Facilitate the inventory process.

• Make it easy to detect variance levels in inventory.

With such a system, the records generated and kept are extensive and valuable. You will have records of what you purchased, product specifications, your primary and alternative suppliers, price, and unit of purchase. Equally important, reports will indicate the usage level of the product between deliveries. These statistics allow for month-to-month comparisons to be made between units in a multi-unit operation.

LABOR PRODUCTIVITY

Labor costs and turnover are serious concerns in today’s restaurant market. Increasing labor costs cannot be offset by continuously higher prices without turning customers away. Maximizing worker productivity so few can do more has become a key challenge to the restaurateur. It is especially true because the food-service industry continues to be an entry-level arena for the unskilled and uneducated. Qualified applicants are still few in the restaurant industry.

A few of the causes of high labor costs and low productivity are poor layout and design of your operation, lack of labor saving equipment, poor scheduling, and no regular detailed system to collect and analyze payroll data. The following are some suggested ways management can improve these areas for greater efficiency:

• Scheduling. The key to controlling labor costs is not a low average hourly wage, but proper scheduling of productive employees. Place your best servers and cooks where you need them most. Know the strengths and weaknesses of your employees. Staggering the arrival and departure of employees is a good way to follow the volume of expected customers and minimize labor costs during slow times.

• On-call scheduling. When your forecasted customer counts are inaccurate, scheduled labor must be adjusted up or down to meet productivity standards. Employees simply wait at home to be called if they are needed for work. If they do not receive a call by a certain time, they know they are not needed. Employees prefer this procedure to coming in only to be sent home, especially tipped staff who do not want to work when business is slow.

• On-break schedules. When you cannot send someone home, you can put him on a 30-minute break and give him a meal. The 30 minutes is deducted from his timecard and you can take a credit for the cost of the meal against the minimum wage.

BEVERAGE CONTROLS

Pricing of beverages is not just a cost-markup exercise. The markup of alcohol in restaurants is lower than in bars where liquor makes up the majority of sales. Prices reflect the uniqueness of an operation and the overhead operating costs. To monitor your liquor costs accurately, you need to record the sales of each type of beverage separately. Separate keys for wine, beer and spirits on your register or a point-of-sale system need to be used. Unless an electronic system is used a detailed sales mix is difficult to obtain.

Your alcoholic beverage purchaser or buyer is responsible for ensuring adequate amounts of required spirits are on hand. Unlike food and supplies, they are not required to shop around for the best deal for the following reasons:

• Specific brands are only sold by specific dealers.

• Wholesaling of alcohol is state regulated and controlled.

• Prices are published in monthly journals and there is little change from month to month.

• Only quantity discounts are available.

• Purchase is done by brand name.

Purchasing and ordering alcohol is therefore much simpler than purchasing and ordering food, but the need to inventory correctly is no less crucial. Alcohol needs to be guarded and inventoried more rigorously because of its cost, ease of theft, and possible abuses. Liquor inventory should be kept locked in different storerooms, cages, or walk-ins than other inventory. Only authorized individuals should have access to these areas and requisitions must be filled out to record withdrawals.

I recommend replenishing your stock by trading stamped empty bottles for stamped full bottles. These prevent bartenders from bringing their own bottles in and selling them. It is virtually impossible to detect without marked bottles because there will be no inventory shortages. If you have drops in sales levels of $50 to $100 in one night, it is a sign of phantom bottles in your inventory.

Inventories need to be audited to ensure your liquor is actually in the storeroom and deliveries need to be checked for accuracy. It is recommended that a purchase order — and not the driver’s invoice — be used to verify deliveries. Controls for determining dispensing costs, recording sales, and accounting for consumed beverages can be done three different ways:

1. Automated systems that dispense and count. These range from mechanical dispensers attached to each bottle to magnetic pourers that can only be activated by the register. These systems are exact, reduce spillage, and cannot give free drinks. Basically, liquor cannot be dispensed without being put into the system.

2. Ounce or drink controls. Requires establishing standard glassware and recipes; recording each drink sold; determining costs of each drink; comparing actual use levels to potential consumption levels; and comparing actual drink cost percent to potential cost percent.

3. Par stock or bottle control. A matter of keeping the maximum amount of each type of liquor behind the bar, then turning in all empty bottles for full ones. No full bottles are given without an empty one coming in. A standard sales value per bottle is determined based on the drinks it makes. A sales value is determined from consumption and compared to actual sales for variances. If less was sold than consumed, investigate.

Standards at the bar are as important as in the kitchen. Regular inventory also needs to be done to watch for fraud and theft and management needs to be expected to meet set standards. Whenever there is a managerial shift change, you must verify inventory to make sure that numbers reported are actual and have not been adjusted to meet costs.

Computerized Inventory Controls

There are a number of computerized systems available that can help with this process. To follow are some examples:

• AccuBar is an excellent example of a computerized inventory system. Customers report a 50 to 80 percent time savings when using the AccuBar system. It’s easy to learn: most users are up and running within 30 minutes. The patented technology eliminates the need to estimate levels; simply tap the fluid level on the bottle outline. Once you tap the bottle outline, data entry is complete. There is no further human intervention. Since no data entry or third party is involved, reports are generated immediately. It also provides a running perpetual inventory. Transfers between locations and returns of defective items are also covered. AccuBar also helps gauge which items aren’t selling, allowing you to consider stocking something else that might bring a better return. AccuBar also recommends what needs to be ordered from each supplier based on current perpetual, par, and reorder points. The order is totally customizable. When a shipment arrives, simply scan the items; any discrepancy from what was ordered is caught immediately. AccuBar can also track food, glassware, china, and other essentials.

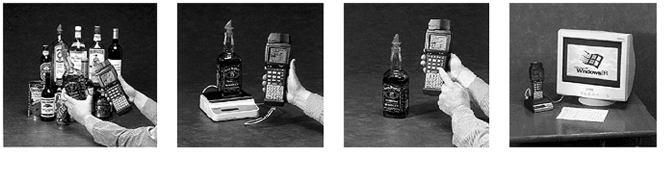

• The Accardis Liquor Inventory System is another option to save time and money and eliminate over-pouring and theft. Since 1987, Accardis Systems has been controlling liquor inventory costs. Accardis was the originator of scanning and weighing bottles to control inventory. The alcohol inventory system has proven to be fast and accurate. It will lower your costs while increasing your profits. Most clients recover the cost of the liquor inventory system in only a few months. The Cyclops Falcon scans and weighs liquor bottles electronically and then downloads the data to the PACER 4.0 for Windows software. Pacer prints out all the management reports on a station-by-station basis. The liquor inventory system also tracks all purchases and requisitions and can be used for liquor, beer, wine, supplies, hats, T-shirts, etc. Cyclops Falcon gives the user complete control of beverages at a fraction of the cost of most other systems. For more information, contact Accardis Systems, Inc., 20061 Doolittle Street, Montgomery Village, MD 20886. Call 800-852-1992 or visit www.accardis.com.

Cyclops Falcon Inventory System Overview: First, identify the product by scanning the bar codes or using the find key. Next, weigh open bottles. Quantities are automatically sent to CYCLOPS with precise electronic accuracy. Third, enter quantity. Use the keypad to enter full unit quantities or to estimate open bottles if scale not used. Finally, generate reports and download data to a PC via the Falcon Docking Cradle.

Controlling Pouring

You want to give your bartender the tools needed to create drinks according to your specifications. By eliminating over-pour and spillage, bar owners and managers save money on every bottle served. If your bartender over-pours just 1⁄8 ounce per drink, your loss could be up to four drinks per bottle.

Liquor-control systems (LCS). Use of technologically advanced portion-control systems is becoming increasingly commonplace in today’s drinks industry. LCSs are particularly effective at controlling liquor costs. They can also virtually eliminate employee theft. LCSs are marketed on the basis of a typical return on investment within 12 months. The following suppliers offer LCSs:

• Berg Company, www.berg-controls.com, 608-221-4281

• AzBar, www.azbaramerica.com, 214-361-2422

• Bristol BM, www.bristolnf.com/liquor.htm, 709-722-6669

• Easybar Beverage Management Systems, www.easybar.com, 503-624-6744

• Precision Pours, www.precisionpours.com, 800-549-4491

• Easybar Beverage Management Systems (www.easybar.com) has multiple solutions for beverage portion control. The Easybar CLCSII is a fully computerized beverage-dispensing system that controls beverage pour sizes, improves bartender speed, and ensures perfectly portioned drinks and cocktails. This system also prevents product loss by eliminating over-pouring, spillage, breakage, and theft. It accounts for all beverages dispensed through the system and boosts receipts by lowering costs and increasing accountability. Also available is the Easypour Controlled Spout System. This offers control for drinks that are dispensed directly from a bottle. The controlled pour spouts allow only preset portions to be dispensed and will not allow drinks to be dispensed without being recorded. Easybar’s Cocktail Station creates cocktails at the touch of a button. The cocktail tower can dispense up to 48 liquors plus any combination of 10 juices or sodas. It mixes cocktails of up to five ingredients, and ingredients dispense simultaneously to cut pour time. All ingredients dispense in accurate portions every time.

• Precision Pours (www.precisionpours.com) manufacturers measured liquor pours, gravity-feed portion control systems, and bar accessories. By eliminating over-pour and spillage with the Precision PourTM 3 Ball Liquor Pour, users save money on every bottle served. The Precision PourTM 3 Ball Liquor Pour allows bartenders to pour liquor with one hand while mixing with the other, speeding up drink production. Also, since there is no need to use a messy shot glass, additional time is saved on cleanup. It also strictly regulates alcohol. A drink that is too strong will likely reduce the number of drinks customers will order and discourage repeat business. Your customers want their favorite drinks to taste like their favorite drinks. Pour them a stiff one and you’re not doing them any favor. Under-pour and you’re likely to rile them. With the Precision Pour™ 3 Ball Liquor Pour, you’ll get the same great taste every time, no matter who’s pouring. The Precision Pour™ 3-Ball Liquor Pour features:

o A new third ball bearing to guarantee accuracy.

o A primer ring surrounding the ball bearing to ensure no sticking, even with cordials.

o A bottom made from a solid piece of surgical plastic guarantees that the ball bearings cannot fall out into your bottles.

o A new cork that will fit all your liter bottles including Absolute, Crown Royal, and Jack Daniels.

Free Pouring

Another alternative for controlling the amount of liquor is to use the free pour. In the free pour, the bartender uses liquor pour spouts or shot glasses to measure liquor amounts. The liquor is measured and then mixed into the drink. Bar management does lose control of the amount poured in this system because the bartender is the one controlling the pours, but this is not a problem if you trust your bartender to pour the amounts you have designated for each drink. The advantages of free pouring include more showmanship and personality to each drink, which many customers prefer, and less expensive setup of materials needed. The free-pour system does rely more on a dependable and skilled bartender, however.

Modern technology has influenced free pouring as well. BarVision combines free pouring with wireless liquor inventory control. It allows you to track liquor inventory usage automatically in real-time. Every pour is transmitted to BarVision by a wireless liquor pour spout. Every empty liquor bottle is reconciled automatically—eliminating the need for manual inventory procedures. BarVision reports provide extensive flexibility, whether you need a usage summary for a quick grasp on your open liquor inventory or a journal detail for reconciling your POS/register receipts. It does not require extensive wiring or hardware installation.

Here’s how it works:

1. Bartenders free-pour drinks.

2. The pour spouts transmit data about the pours to the receiver.

3. BarVision “talks” to the receiver and keeps a journal.

4. Managers print reports from BarVision’s journal.

For more information, visit www.barvision.com or call 480-222-6000.