![]()

Chapter 13: Food Buying Techniques

This information will be valuable for people who place large orders. The first step is to determine whether large food orders are advantageous for you. Smaller orders have the advantages of offering:

• Lower storage cost for less risk, less inventory, less paperwork to maintain.

• Greater freshness for less risk of spoilage.

• Easier financial handling.

• Opportunity to take advantage of lower prices when they drop.

• Reduction in storage space.

• Greater flexibility in working with vendors.

• Less chance of theft due to having less inventory.

To make an educated decision, consider the advantages of placing large orders:

• Products can be purchased at a lower price when bought in quantity.

• There is less chance of running out of items.

• More stable prices mean more effective menu pricing.

• Buyer has more time to focus on other responsibilities.

• Lower labor cost to place, receive, and store orders.

Presented here are various items to be purchased, tips to find the best quality, and negotiating the best price for your facility.

MEATS

Meat may be the most important food item for your facility. Usually one-third to one-half the food budget is spent on meat products because they are costly and most entrees contain meat. Red meats are more expensive because each cow produces only one offspring a year. In turn, a sow may produce several dozen pigs and a hen produces several hundred chicks. Another difference is the length of time it takes the animal to mature enough to go to market. Here are some of the differences:

|

Animal maturity to market timetable |

|

|

Cattle |

18 months |

|

Chickens |

12 weeks |

|

Fish or Other Low Cost Seafood |

Several weeks |

|

Hogs |

6 months |

|

Veal or Lamb |

3 months |

These numbers show a drastic difference in the length of time from farm to market for beef compared to other meats.

Transporting animals to market is another costly factor. Most cattle are raised in grasslands far removed from large cities. The amount of food required to fatten cattle is significantly higher than for fish and poultry. It takes seven pounds of feed for cattle to gain one pound. Other ratios are: fish, 1:1; chickens, 2:1; and hogs, 4:1. Each of these factors pushes the price for the consumer and the restaurant manager.

Meat usually sets the tone for a meal, so the buyer needs to understand properties of meat, how to pick the best quality, and meat preparation that affects what cuts or parts should be purchased. If there are any questions, speak with the cook before making the final purchase or else the menus could fail.

PROPERTIES OF MEAT

Raw, unprocessed meat is made up of 45 to 72 percent moisture and the remainder is protein, bone, and fat. The muscle in meat is made up of long fibers bundled together with a threadlike appearance. Fibers that make up the muscle contain fats, flavor minerals, moisture, proteins, vitamins, and other compounds. Younger animals have fine fibers that become coarse with age. These fibers are moist without being sticky and they have a nice color with a soft sheen indicating a good quality and tenderness, an important characteristic directly related to the amount of connective tissue. Younger muscles are more tender, but the care and feed an animal is given also makes a difference. Animals confined and fed well are apt to be tender.

Meat that has slightly more collagen than elastin can be cooked to become more tender, but meat with high elastin will remain tough. The length of time meat is cooked makes a difference in the tenderness. Here are some specifics:

|

Cooking Types and Tenderness |

|

|

Raw |

Most tender |

|

Rare |

Less tender |

|

Medium |

Begins to toughen |

|

Well Done |

Tough |

If you plan to cook meat until it is well done, you need to choose a tender meat to begin. As meat is heated, it begins to coagulate and shrink because juices are cooked out. You can control the amount of shrinkage by using lower heat. Low shrinkage allows the meat to retain more flavor and you get more servings from it; 15 to 20 percent shrinkage is low.

Bones increase weight and cost of meat although there is some added flavor to the meat near the bones. It is good to crack the bones and add some water to reach the marrow for added flavor. By adding a little acid to stock made with the bones, you can produce a soup richer in calcium than a glass of milk.

The trend to eat less saturated animal fat is expected to continue, so cattle is being raised to produce less fat and more fat is being trimmed from meats. Age and feed determine the amount of fat in meat. Younger cattle have less fat and well-fed cattle have a higher amount of fat. Higher grade contains more fat. There are three types of fat:

• Body Cavity Fat: Located inside the body, it starts on the kidneys and heart and spreads over time.

• Finish Fat: Located away from organs, it starts on the shoulders and rump and moves downward and forward with time.

• Marbling: Located in the muscles, fat appears as tiny flecks.

Fatty tissue contains 15 to 50 percent moisture, keeping the meat moist during dry cooking. Roasts are cooked upside down so the fatty juices can roll down over the meat. Turkeys are cooked backside up since that is where the fat is located. Another cooking tip is to cook lean meat in moist heat. When you try to sauté or broil lean meat, you often need to add some fat. Keep in mind that fat adds flavor and richness, but it also adds calories and cholesterol.

Myoglobin and hemoglobin make meat look red. When heat touches meat, they change to hematin, a gray pigment — the color of well-done meat. When oxygen combines with myoglobin, it creates oxymyoglobin which gives ground meat a bright red appearance on the outside but a darker color in the center. If you expose the center of ground meat to the air, it will become bright red too.

When meats are cured with nitrogen, it turns a pink color that we see in ham or corned beef brisket. Beware of brown meats: This means that the meat has deteriorated. When it is wet and slick, it has begun to spoil.

|

MEAT COOKING TEMPS |

|

|

Type |

Temperature |

|

Rare meat is red |

115 – 140˚ F |

|

Medium meat is pink |

140 – 160˚ F |

|

Well done meat is gray |

160 – 175˚ F |

Heat builds on the outer surface of meat, so it is good to remove the meat from the heat before it reaches the desired core temperature.

THE MEAT MARKET

Meats have changed dramatically in the last 50 years because of improved breeding and production methods to produce more tender animals with higher meat yield. Research is being done to reduce the amount of fat animals develop. Meat is also being brought to the market younger. New scientific feeding practices promote faster growth on less feed to produce leaner animals. The practice of shipping animal carcasses has changed so that most meats are broken down and bones removed before shipping to cut shipping weight, size, and costs. All of these improvements provide a more valuable product.

Prices at all sorts of markets fluctuate, meaning that buyers need to adjust to trends and conditions. The USDA provides free daily information about market conditions, slaughter amounts, and current prices. Some of the publications you might want to check include:

• Urner Barry Publications, Inc., PO Box 399, Toms River, NJ 08754.

• The National Provisioner Daily Market Service (“yellow sheet”).

• The Hotel, Restaurant, Institutional Meat Price Report (“green sheet”).

• USDA Publications — www.usda.gov.

• Market News Service Report.

• Meat Sheet for Boxed Meat Items.

• Price Analysis Systems, Inc., P O Box 9626, Minneapolis, MN 55408.

• Meat Price Relationships — published every two years. The historic prices of 74 meat and poultry items are listed along with the seasonal charts. They also predict future prices that are useful for planning, budgeting, and projecting sales and promotions.

The federal government has prevailed over the meat market for almost 100 years. The Jungle by Sinclair Lewis, published in 1906, caused widespread concern, prompting President Theodore Roosevelt to create a panel inquiry into actual conditions. Congress passed the Meat Act in 1906 to control operating standards that meat processing plants must follow, allowing for a series of inspections to guarantee meat is “fit for human consumption.” Federal inspectors stamp the meat when it has met requirements. When the meat does not pass inspection, they are stamped “condemned,” “retained” for further inspection, or “suspect.”

The stamp indicates the official establishment number that will help you determine where your meat actually originated. Check the number on the stamp against the federal list and you will know. Here are some samples.

Inspections are required by law, but grading is voluntary. When a packager puts its own “brand” on the meat, they do not have to give it a grade. The grading process was established in 1927 and the company or buyers who request grading paid an additional cost which is passed along to the consumer. Grades have been established for beef, lamb, pork, and veal. Beef has a variety of grades since there are so many different cuts and types of animals. Grading was amended in 1967 by the Wholesome Food Act which tightened the standards and gave control to state and federal governments. Some states have more stringent rules than the federal government in which case they can inspect and stamp the meat.

FROZEN MEAT

Large ice crystals can form on frozen meat so fast freezing is recommended so that only small crystals form. Slow freezing also causes a loss of moisture, flavor, minerals, and vitamins. If you cook meat from a frozen state, you can prevent some of these losses, but doing so increases the cooking time. Freezer burn is caused when the surface of the meat becomes dehydrated. It can be minimized by enclosing items tightly with moisture-proof wrap to eliminate air. Dry-paper cover toughens the meat and does not prevent freezer burn and flavor loss. You should also be sure to label all your frozen meat while in inventory to make sure it is used on a timely basis. DayMark Safety Systems offers CoolMark™ freezable labels which stick to all frozen surfaces. For more information call 800-847-0101 or visit www.daymarksafety.com.

You might want to consider the cost to store frozen meat compared to making smaller purchases of fresh meat. This chart shows how long meat can be frozen under good quality conditions.

|

FREEZING MEAT |

|

|

Beef |

Lasts the best |

|

Cured or Smoked Meats |

1-3 months |

|

Ground Meat |

3 months |

|

Lamb |

Lasts the best |

|

Pork |

Not as well, fat becomes rancid |

|

Veal |

Lasts well |

To be an effective meat buyer, you need to understand the classification and grading system used. Kinds of animals include beef, pork, sheep, and veal. There are additional classifications that include: cured meats, edible by-products, and sausage. Be aware of the prepared, canned, and substitute meat items available.

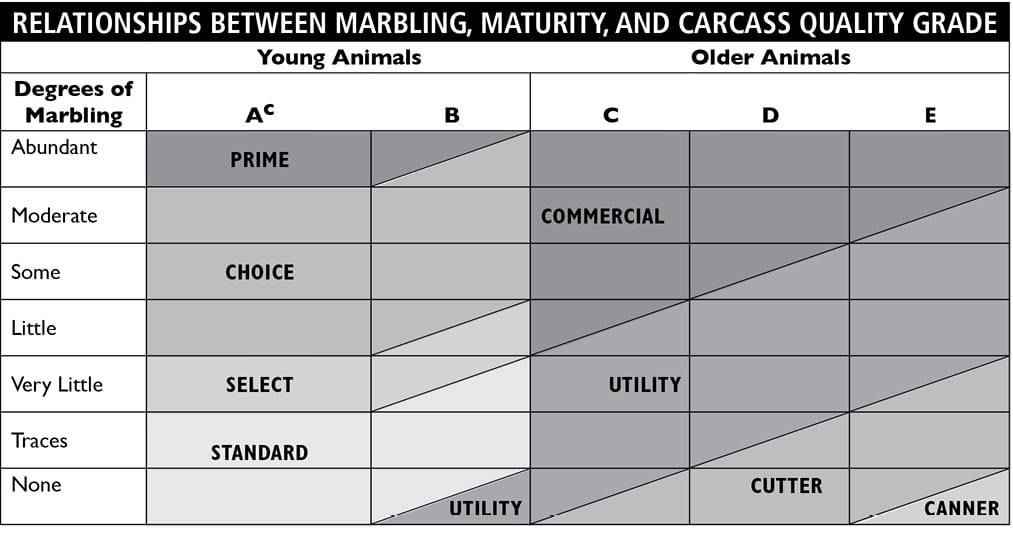

Two grading systems are used. One determines quality while the other is based on yield; age, maturity, and quality are all factors that determine the grade of beef. There are seven classifications that go from devoid (none) or slight to moderately abundant (heavy marbling).

The chart below shows how grades are determined based on the variables.

Bones are graded based on their size, shape, ossification, amount of cartilage, and interior (marrow) color. These factors are indicators of the age of the animal. Younger animals have less ossification and more cartilage. The bones change shape as the animal matures. Interior bones have more red in younger animals than in older animals.

Flesh color is pink in young animals, but the color does redden with age. When you touch the flesh, it should be moist without being wet or slimy. Fibers in the meat should be silky with a soft sheen. These fibers are coarser in older animals.

Veal and calf grading are similar to beef grades although muscle structure is a factor. High grade veal and calves must have wide, thick carcasses with plump-muscled legs, shoulders, and breasts. Thin animals are graded lower.

In pork grading, age is the main factor based on body size, flesh color, and bone characteristics. Breaks in the bone indicate the animal’s age. Younger animals have sharp and ragged breaks while older animals’ breaks are smoother.

IDENTIFYING PORTIONS OF MEAT

You must know the differences between the cuts of meat and between the muscle and bone formations to recognize various cuts of meat. When you look at a porterhouse steak and a T-bone, the biggest difference is the size of the tenderloin muscle. In a T-bone, the muscle is smaller. I have always found the shape of the bone makes it easy to recognize a T-bone. Remember that it takes practice to identify the various cuts. The buyer and receiver need to be familiar with these details. For a wealth of information on meat identification, see this website: www.ffaunlimited.org/meevandte.html. You can find many specifications at www.ams.usda.gov/LSG/stand/imps.htm. Some of the publications you can download include:

|

IMPS Files for Download |

||

|

Series No. |

Name |

File Size |

|

-- |

General Requirements – pdf file |

62 Kb |

|

-- |

Quality Assurance Provisions – pdf file |

356 Kb |

|

100 |

Fresh Beef – pdf file |

582 Kb |

|

100 |

Fresh Beef with Pictures – pdf file |

2 Mb |

|

200 |

Fresh Lamb and Mutton – pdf file |

668 Kb |

|

300 |

Fresh Veal and Calf – pdf file |

218 Kb |

|

400 |

Fresh Pork – pdf file |

324 Kb |

|

500 |

Cured, Cured and Smoked, Cooked Pork Products – pdf file |

168 Kb |

|

600 |

Cured, Dried and Smoked Beef Products – pdf file |

982 Kb |

|

700 |

Variety Meats and Edible By-Products – pdf file |

45Kb |

|

800 |

Sausage Products – pdf file |

119 Kb |

|

11 |

Fresh Goat – pdf file |

970Kb |

For copies and other information concerning the IMPS write:

USDA, AMS, LS, SB

1400 Independence Ave., SW, Stop 0254

Washington, D.C. 20250-0254

To contact them call 202-720-4486 or e-mail Thavann.Un@usda.gov.

Wholesale and retail cut charts can be helpful in identifying portions of beef, lamb, veal, and pork. See charts from the USDA at www.usda.gov.

PROCESSED MEAT

Processed meat can be restructured, smoked, or cooked to preserve the meat, give it more flavor, or reduce labor costs — processes that are monitored by the federal government.

Nitrites or nitrates can be added to bacon, ham, and sausage as a preservative. After 1979, meats cured without nitrites or nitrates have a label that reads, “not preserved; keep refrigerated below 40˚F at all times.” Large canned meats can contain the same label because of their size. They may be considered fresh meats.

Cooked processed meats come in many varieties, including canned, frozen, and chilled. Some are refrigerated or frozen items which can be offered in bulk or portion packages. There is a greater chance of bacterial concerns with these products, so it is advisable to enforce bacterial standards. The federal government requires a minimum amount of meat in each of these products.

Cured meats are salted or smoked. Salting means soaked in brine or pumped with brine for preservation. Curing offers a better flavor, improved appearance, and a more tender product. These are some terms for cured meats and an explanation about what each term means:

• “Country Cured.” Meat is given a dry cure (see below) with a combination of sugar, spices, and honey. (Beef cured like this is called “cured beef brisket.”)

• “Cured.” The finished weight is the same or less before curing.

• “Cured, Water Added.” Finished product is 110 percent of weight before curing.

• “Dry Cure.” 8 to 9 percent salt or preservatives are added to bring out the meat’s juices, making brine that soaks into the meat, preserving it.

• “Imitation.” More than 110 percent added weight after curing.

• “Wet Brine Cure.” Meat is immersed in 55 to 70 percent salt and soaked enough to preserve the meat.

Bacon is the most popular cured meat. It looks pink and dry, but not greasy. It usually comes in eight to ten pound slabs. Ham is usually 12 to 14 pounds.

Edible meat byproducts are less well known but are still offered for consumption. Various types are classified as delicacies. These are some of the possibilities.

• Brain. Veal brains are common.

• Heart.

• Kidneys. Beef and lamb are commonly used.

• Liver. Calf and veal liver are the best. Lamb and pork liver are good. Beef liver is tough unless it is cooked quickly.

• Oxtails.

• Stomachs. First and second stomachs from cattle.

• Honeycomb tripe from the second stomach of cattle.

• Sweetbreads.

• Tongue. Beef tongue is the most common.

• Sausage. Ground meat combined with spices that vary depending on which type is being made. Nitrite is added to reduce bacterial risk. Most sausages must be refrigerated. See note below for ones that do not have to be refrigerated.

A number of ground meats are classified as sausage. These include:

• Cured Sausage – Good for 30 days, but fresh is good for one week.

• Frankfurters – Refrigerate.

• Pepperoni – Not refrigerated.

• Salami – Not refrigerated.

Canned meat can be a good alternative if fresh meats are not available. They are also a good choice when refrigerated or frozen storage is an issue. Some canned meats need to be refrigerated at 40 to 70 degrees Fahrenheit. Canned meat should not be kept for more than a year.

Some of the canned meat varieties include boned chicken or turkey, corned beef, luncheon meats, pork sausage, links, Vienna sausage, frankfurters, chili con carne, and canned ham.

POULTRY

Poultry and eggs are a huge industry that changed little until the last quarter of the 20th century. It changed dramatically because science enabled growers to raise heavier chickens in about half the time previously required.

Today thousands of chickens lay eggs in large henneries. A bit of chicken trivia — the average hen lays more than 260 eggs a year. Eggs are a wonderfully versatile and inexpensive food, but demand has decreased because they are high in cholesterol.

Turkey and chicken are high in protein and cost little so the demand grows. Both are incredibly versatile and low in cholesterol and unsaturated fats. In 1956 the government began to require that all poultry products be inspected. After an item passes inspection, it is stamped “Inspected and Passed.” When poultry is processed, these are the steps needed: it is killed, bled, scalded, plucked, eviscerated, and inspected. Following are some details about the inspections performed to evaluate poultry products. Poultry items can be purchased cooked or raw.

SPECIFICATIONS

The specifications used to evaluate poultry include the following:

• Kind–Poultry or Game Birds. Poultry includes chickens, turkeys, ducks, geese, and pigeons. Game birds include pea fowl, swans, quail, wild ducks, geese, and pheasants. Rabbits are also classified as poultry.

• Class. This is based on the age and the sex of poultry.

• Grade or Quality. Standard poultry grades are A, B, and C. Grade is based on a list of characteristics and qualities. These include conformation, fleshing, fat coverage, and lack of feathers, tears, cuts and bruises, freezer burn, and disjointed and broken bones.

• Packaging. Frozen poultry is wrapped in polyethylene to eliminate or limit freezer burn. The number of items in each container is determined by the type of poultry item being packaged. Chicken is usually 12 to 24 per container. Turkey, duck, or geese are 2, 4, or 6 per container. Parts are 25, 30 or 50 pounds per container

• Style. Includes whole, halved, quarters, and parts. Parts are drumsticks, legs, thighs, legs with pelvic meat, wings, and breasts.

• Size, Weight, and Portion. Vary depending on the kind of poultry.

• Transportation and Delivery Temperature. Frozen core temperature of poultry items is 0 degrees Fahrenheit and the refrigerated temperature is 36 to 40 degrees Fahrenheit.

EGGS

Every restaurant needs a reliable egg supplier. Be sure that your facility and your supplier refrigerate eggs right away. Eggs that are graded wrong can drive your price up unnecessarily. The longer they are exposed to room temperature, the lower the quality. Eggs can be purchased in these forms: in shells, as liquid, frozen, and dried. The type you need will depend on what you plan to prepare. I will discuss that in more detail shortly. Another interesting bit of egg trivia – the weight distribution of an egg is: white = 58 percent; yolk = 31 percent; and shell = 11 percent.

Shells are a factor in the grading process and are graded on soundness, cleanliness, shape, and texture. Scanners are used to see the interior of the egg for grading and they allow the inspector to see the centering of the yolk, the aqueous nature of the white, size of the air cell, blood spots, and any deficiencies. Remember that eggs will last for several weeks if they are refrigerated properly. Egg Standards are Grade AA, A, B, and C. This table shows how the grading process works.

|

U.S. Standards for Quality of Shelled Eggs to Meet Quality Factors |

|||

|

Factor |

AA Quality |

A Quality |

B Quality |

|

Shell |

Clean, unbroken, almost normal |

Clean, unbroken, almost normal |

Clean or slightly stained, slightly abnormal, may be bubbly |

|

Air Cell |

1/8” or less deep, almost regular |

3/16” or less deep, almost regular |

3/8” or less deep, free or bubbly |

|

White |

Clear and firm |

Clear and reasonably firm |

Clear, may be weak |

|

Yolk |

Outline is refined slightly, mostly free from defects |

Outline fairly defined, mostly free from defects |

Outline may be defined, slightly enlarged, flat, and may show defects although not serious |

Processed eggs are frozen or dried and must be pasteurized. When you consider what type of eggs to use in your facility, evaluate what will be made with them. If they will only be used for cooking and baking, various cheaper options are available. The chart below will show you the egg equivalents to aid in your choice.

Frozen eggs are high quality eggs used for French toast, omelets, and scrambled eggs. Lower quality eggs can and are used for cooking and baking. Frozen eggs also tend to produce a tougher finished product.

Dried eggs whites are used for meringue. “Egg Beaters” are a common product used to eliminate the yolks and lower cholesterol. To prevent salmonella from fowl, keep eggs and poultry refrigerated below 45 degrees Fahreneheit and use safe, sanitary handling and cooking methods at all times.

tHE MARKET

The poultry and egg market is volatile because of the quick turnaround time for producing poultry and eggs. Market reports are published daily. They help you to follow the poultry market when planning menus and to ensure your supplier’s prices are in line. Market reports can be valuable if your facility uses a large quantity of eggs.

SELECTING FRESH PRODUCE

The fresh produce market is complex and it becomes more important as people want healthier foods. This chapter will walk you through the processes needed to buy fresh produce in the best way. An interesting tidbit is that the consumption of processed fruits and vegetables has decreased while fresh fruits and vegetable consumption has increased.

REGULATIONS

You should know the regulations that guide the produce market. Here are a few of the most important.

The Agricultural Commodities Act of 1938 requires that people in the produce business be licensed and use fair business practices. Market quality and procedures improved because of this act. The Agricultural Marketing Act of 1953 and 1957 created agencies that established standards and grades for foods. The Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Division established the 160 grading standards that we have today. The Food and Drug Act also provides standards that affect the plant operations, identification, labeling, and other processes affecting fresh produce. Since 1990 prepackaged items have been required to list nutrition information.

NUTRITION

People are demanding more fresh produce as they learn how healthy they are. They offer a high vitamin content — one serving can give a daily supply of Vitamin A and C. They provide calcium, iron, phosphorous, and potassium — and no cholesterol.

Complex carbohydrates, the healthiest kind, can be found in corn, legumes, potatoes, and squash. Some produce items also offer protein and fiber. It is recommended that people eat at least four servings of fruits and vegetables each day.

THE PRODUCE MARKET

The produce market can be affected overnight by a storm in California or a frost or hurricane in Florida. There are times when the market has too much of some items and not enough of others.

Science has had a profound effect on the produce market as advances help produce stay fresh longer. Flavor and freshness are much better with improved packaging and atmospheric control. We can create a better appearance and make produce tastier and more nutritious.

When produce is picked, it contains “field heat.” The temperature needs to be raised to maintain freshness. The old way was to refrigerate produce, a slow process. Another process, hydrocooling, uses ice and water, but it is expensive. Vacucooling, a dry system, is the preferred method of cooling. A large amount of the item is pulled into a tightly sealed chamber which uses the heat in the items for evaporation. It is low cost and handles large quantities of produce quickly.

Improved shipping methods are changing the market. Items get to their destination much faster. Harvesting, cleaning, trimming, packaging, and weighing are done in the field. Produce is then cooled and transported to market on refrigerated trucks.

Packaging options have changed the produce market. Stronger packaging is being used to protect produce en route. Special wraps are used during shipment to ensure better appearance and a fresher flavor and bacteria static wraps are used to combat bacteria growth in items while they are being stored or shipped. Two terms for new wraps are CAP and MAP packaging, which stand for “controlled atmosphere packaging” and “modified atmosphere packaging.”

Another factor that affects the market is the introduction of new varieties of produce including the number of tropical fruits that have been brought into the U.S. market and U.S. growers are raising these items as well. Kiwi is an example of a fruit that was once scarce. It was shipped from New Zealand in containerized compartments that were loaded directly onto trucks. Now kiwis are produced in California.

Prepared fruit is another option to consider. Some facilities have eliminated fresh raw fruits and vegetables and are using prepared produce to eliminate waste and reduce equipment, space, refrigerator space, and labor needed to prepare the items. As labor costs increase, prepared produce could become even more popular with food service managers.

The season of the year can make a difference in availability and price. Most fresh produce grown in the United States is available from spring through fall. Imported produce is ungraded and varies more than items grown in the United States. It is critical that the manager and buyer know what areas produce the best products.

RERISHABLE ITEMS

Fresh produce needs to be handled properly. If it is stored in elevated temperatures, quality is compromised. Every 18 degrees Fahrenheit elevation in temperature doubles deterioration. Produce needs to “breathe,” requiring cool temperatures and good ventilation. Here are items that should be stored separately because they emit high amounts of ethylene which accelerates deterioration of nearby produce:

• Apples

• Apricots

• Berries (not cranberries)

• Cherries

• Figs (not with apples)

• Grapes

• Peaches

• Pears

• Persimmons

• Plums and Prunes

• Pomegranates

• Quinces

Not being familiar with the times for deterioration can cause waste and soaring food costs. It is also important not to buy items that are already ripe unless you plan to use them right away.

PURCHASING PRODUCE

What if your supplier insists that you must order a specific amount of produce? An example would be if you want to order three and a half crates, but they require you to buy four crates, which is quite common. When this situation arises, check your menu and see where you can make adjustments to use the additional items. When produce is delivered, there are specific things you or your receiving person needs to confirm: amount, condition, damage, grade, net weight, packaging, rot, size, and pest infestation.

Standard grades for produce are U.S. No.1, No. 2, No. 3, Combination Grade, and Field Grade. U.S. No. 1 is the most desirable grade. Combination Grade is a combination of items which fall in each grade. Field Grade is the items as picked.

When you figure quantity, include item count, packaging, and net weight. With produce, a variety of packaging may be used, a reason for you to be specific about net weight in your specifications. Many times, the quantity will be whatever amount fits in a certain size container. Several packaging terms include.

• “Loose pack.” Items are haphazardly placed in a package.

• “Struck Full.” Items are packed just below the top and scraped off if needed to level the contents.

• “Fill Equal to Facing.” The quality of the items on the top are equal to the quality of the products below the top and throughout the package.

It is important that you be familiar with the quantity of fresh produce to order so that you have enough to prepare food on your menus. A wonderful resource is the Quantity to Order of Fresh Vegetables in the USDA Agricultural Handbook. There is also extensive information in the book Quantity Food Purchasing by Lendal H Kotschevar and Richard Donnelly by Prentice Hall in Upper Saddle River, New Jersey 07458.

PROCESSED FOODS

The processed food market is complicated partly because many government regulations are in place to oversee it. Producers and manufacturers are a small indication of the number of people who are involved in the industry. Foods are produced in bulk and then passed on to consumers or food service facilities.

REGULATIONS

There are many regulations that affect processed foods, but there are several especially important to food service managers and buyers. One is the Pure Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act which regulates what can and cannot be added to foods and sets acceptable labeling standards. The Agricultural Act gives the USDA authority to set quality standards for processed foods and should be taken seriously.

Grading

Earlier we discussed the need to establish the grade, brand, and quality desired when you establish your order list with each vendor. At times a seller may buy a product and later determine the brand after evaluating the quality. It is good for a restaurant manager or buyer to be familiar with the usual quality of different brands to know which brands to avoid.

Surprisingly, sellers are not required to list product quality on their labels, another reason it is good to know which brands consistently offer a better quality product. The table below shows how an educated manager or buyer can identify the quality of the products from the label.

|

Federally Approved Grades for Fruits and Vegetables |

|||||

|

Word Terms |

Letter Terms |

||||

|

Fruits |

Vegetables |

Fruits |

Vegetables |

Score |

|

|

Top Grade |

Fancy |

Fancy |

A |

A |

90-100 |

|

Second Grade |

Choice |

Extra Standard |

B |

B |

80-89 |

|

Third Grade |

Standard |

Standard |

C |

C |

70-79 |

The government does not recognize the word terms to indicate the produce quality, but the market has not caught up with the regulations. By including both techniques, you will be able to understand either designation.

Some items are rated “below standard,” but they are not unusable. “Below standard” will be rated below 70. One example is canned peaches in small pieces. While they do not work as peach slices, they would be great for peach pie or peach cobbler.

Labels

The Pure Food and Drug Division dictates the elements that must be included on produce labels. When items fall below standards, the label must explain discrepancies. The label must list the style pack, variety, any artificial colors, net contents, number of pieces in the package, package size, number of servings, and serving size. The picture on the label must be a real likeness to its contents.

Standards of Identity

When the name is listed on the label it must be the proper name of the actual product in the package. An example would be sweet corn, sweet white corn, kernel corn, or cream corn.

Syrup Density

The label must list the syrup density in the container. Designations include light, medium, heavy, and extra heavy. Variations include lightly sweetened, water packed, or juice packed. Usually the higher grades contain heavier syrups although it is not guaranteed.

Standards of Fill

There are various standards of fill. A couple of these standards are:

• Contents must fill 90 percent of the water capacity.

• “Filled as full as practical.” Without breakage or crushing.

• “Below Standard Fill” or “Slack Fill.” The standard has not been met.

• “Solid Pack.” No water has been added.

• “Heavy Pack.” Water has been added.

METHODS TO PRESERVE PRODUCTS

There are many methods to preserve produce.

• Canning. Before items are canned, they must be washed, sized, graded, peeled, trimmed, and then loaded into the cans. People have found that it is more convenient to have canneries near the production locations. Some canneries are moved into the field to speed up the process. It is recommended that the produce be blanched to hold its color, improve flavor, destroy bacteria, and remove dirt and make rigid items easier to pack. Liquid is added to the cans; they are then closed, exhausted, and sealed. The filled, sealed containers are cooked in steam at a high pressure, and then rapidly cooled. In some cases the inside of the can is finished so the can will not react to the food.

• Freezing. The best way to maintain high quality is by freezing items soon after they are harvested. They can also be blanched to maintain color and destroy enzymes before freezing. When you review your product specifications with any supplier, indicate that you insist on “condition upon delivery should be the quality specified.” The temperature in the transport trucks needs to be around -10 degrees Fahrenheit. If the temperature fluctuates, quality can suffer. If you suspect an item was not stored at the correct temperatures, check for refreezing and large patches of ice on the packages.

• Drying. Drying is the process of removing moisture from items. Once the moisture is removed, microorganisms cannot grow.

These are common drying methods:

• Air Dried. Natural drying and it is slow.

• Sun Dried. Just what it says, drying in the sun, and it is somewhat quicker. You can introduce heated, dry air to speed up the process.

• Vacu-Drying. Reduce air pressure and introduce heat.

• Tunnel Drying. Fast moving warm air or dry inert gases flow through a tunnel holding the produce.

• Spray Drying. Concentrated liquid is sprayed in a chamber and the moisture is extracted.

• Drum Drying. A drum rotates the item, lifts it, and dries it. The item is then scraped from the drum.

• Freeze Drying. Food is frozen and the moisture is pulled from the item with a vacuum.

CONVENIENCE FOODS

Convenience foods are classified as foods prepared for longer preservation at lower labor costs. There are many convenience foods and the list grows more every day. Some of them are high quality and can compete with products made fresh on site.

There are a variety of reasons to consider convenience foods. One would be a limit of skilled labor in your area. Another would be a way to reduce labor costs in a facility. Many facilities find that a combination of convenience foods and fresh foods works best for them. Here are some advantages to preparing items fresh on the premises:

• Overall operating expenses may be less.

• Patrons often place a higher value on homemade foods.

• Your food items can be unique.

• Nutritional value can be higher.

• Ability to limit the amount of additives used.

• More control over the food prepared.

• Less worry about downsizing.

• Convenience food instructions can be confusing or incomplete.

These are some advantages of convenience foods:

• They may be less expensive when you consider all relevant costs.

• It is simpler to track food usage.

• You can eliminate leftovers.

• Your staff requires fewer skills.

• Inventory, purchasing, receiving, and clean up are easier.

• Equipment usage could be less, but a thorough evaluation is needed.

• Menu options can easily be expanded.

• Foods are easy to fix in a short time.

• Product consistency should be guaranteed.

• It is easy to keep items on hand.

A thorough evaluation is needed before making a final decision on whether to buy or make items. Positives and negatives need to be considered based on the situation in each restaurant. Review all details before making a decision for your facility.

DAIRY PRODUCTS

We have all heard the recommendation to drink two- to eight-ounce glasses of milk every day because it is a great source of calcium, protein, and vitamins A and D. You can avoid milk fat by offering low fat and skim milk. Besides milk, dairy products include cheeses, sour cream, yogurt, ice cream, and butter.

Regulation

The dairy industry is carefully regulated by the government because it is easy to contaminate milk products. It is produced every day and there is no effective way to shut off the market temporarily. Milk has a short shelf life, so it needs to be processed and moved to markets quickly.

Pricing

The Federal Milk Marketing Order Program establishes the pricing scale directly affecting more than 70 percent of the milk market and indirectly affecting the remainder. There are three price classifications for milk products:

1. Class 1 – Liquid Milk Products (milk, skim, buttermilk).

2. Class 2 – Soft Milk Products (cottage cheese, creams, ice cream, and yogurt).

3. Class 3 – Hard Milk Products (cheese, butter, and powered milk).

Federal price setting has led to a stable market so that the supply is consistent. There is no “market destroying competition” and dairy prices are reasonable.

SANITATION

Your state and local government set sanitation standards and it is mandatory that they implement standards such as these.

• Herds must be healthy. USDA and public health officials inspect them.

• Milk is obtained under sanitary conditions.

• Milk must be transported in modern, refrigerated, sanitized trucks.

• Milk is tested when it arrives to ensure it meets all relevant standards, including: milk fat content, odor, sanitation, and taste.

• When milk does not meet these criteria, it can be rejected.

When the milk arrives at the dairy plant, it goes through an amazingly fast process. It is pasteurized, cooled, homogenized, and packaged in a few minutes. Pasteurizing can be done at various temperatures, but the highest temperature produces a cooked taste, although they are recommended for heavy milk products. The method of homogenizing milk forces it under pressures of 2,500 pounds per square inch or higher amounts, through tiny orifices which divide fat globules finely so that they are permanently suspended. The milk is packaged in non-returnable containers usually wax-coated or plasticized cardboard. The cardboard blocks any light that destroys the riboflavin in milk.

QUALITY STANDARDS

There are various state and federal standards which govern milk processing and production. Milk must be “fresh, clean cow’s milk free from objectionable odors and flavors.” Vitamins A and D are added to milk. Normal amounts are vitamin D – 400 units and vitamin A – 2,000 units per quart of extra dry milk solids. If you want detailed information, contact your local authorities.

Types of Milk

Quality of milk is based on flavor, odor, quantity of milk fat, and milk solids. Bacterial content can also be used in the grading process.

• Grade A whole milk plate count must be less than 20,000 ml and less than 10 coli form. (Some states dictate no coli form.)

• Certified Milk. Raw milk with plate count over 10,000 ml with no coli form.

• Cultured Milk. Used for dietary purposes.

• Filled Milk. Non-milk fat is added (must be labeled “filled”).

• Flavored Milk. Sweetener or flavoring is added.

• Fortified Milk. Has increased nutritional content, like vitamins A and C.

• Low Sodium Milk. Sodium is replaced with potassium.

• Low-fat Milk. 8.25 percent nonfat milk solids and 2 percent maximum milk fat.

• Milk Drink. Milk fat or milk solids have been altered.

• Skim and Nonfat Milk. 8.25 percent nonfat milk solids and 0 to ½ percent milk fat.

• Soft Curd Milk. Treated to be more digestible; used in baby formulas.

• Soured Milk. Buttermilk is the fluid left when butter is made. Today butter is made from whole, low fat, or skim milk and is soured with bacterial cultures. Some buttermilk products contain small bits of butter. It has 8 to 8½ percent milk fat content and the same milk solids as the milk used to produce it.

• Yogurt. A cultured product with a spoonable consistency. It has 2 to 3½ percent milk fat and 8 to 9 percent milk solids.

• Low-fat and Nonfat Yogurt. Yogurts can also be flavored with fruits or some other products.

Concentrated Milks

• Evaporated Milk. 7.9 percent milk fat and 18 percent nonfat milk solids. It can be homogenized and fortified with vitamin D. It is produced by boiling milk at 130 to 140 degrees Fahrenheit and using a vacuum to extract the moisture.

• Nonfat Evaporated Milk. Generally purchased by the case. You can add 2.2 times the water to evaporated milk to produce whole milk. A 14 ½ ounce can makes one quart of milk.

• Condensed Whole Milk. Contains no less than 19 ½ percent nonfat milk solids, 8½ percent milk fat, and enough sugar is added to prevent spoilage – about 45 percent

• Nonfat Condensed Milk. May be available in bulk but does not have to be sterilized in the cans

• Concentrated Whole Fresh Milk. Can be sold as a liquid or frozen product. There is a 10 ½ percent milk fat content. The ratio used to create whole milk is three to one. When it is sterilized it has a three-month shelf life at room temperature or six months when refrigerated.

Dietary Milks

• Dry and liquid diet foods produced with milk are available for sale. They usually are high in milk solids and have been fortified with vitamins, minerals, and proteins. These can be used for dieting and are offered in various flavors. Baby formula is also offered as dry or liquid products. It is best to check the label to be sure what you are purchasing.

• Dried Milks. Milk solids with only 2 to 5 percent moisture. They must be stored in airtight containers to avoid quick deterioration.

• Whole Dried Milk. Does not contain less than 26 percent milk fat or less than 5 percent moisture.

• Nonfat Dried Milk. Does not contain more than 11 percent milk fat or less than 5 percent moisture. Some precautions – watch for stale taste, a cooked flavor, oxidation, tallowness, caramelization, and any other unusual flavors. Dry milk should be produced from pasteurized milk.

• Spray Dried Milk. The highest quality dried milk. Roller dried milk under a vacuum is also high quality.

• Malted Milk. This is a dried milk product with about 3 ½ percent moisture, 7 ½ percent milk fat, a mixture of 40-45 percent nonfat milk, and 55 to 60 percent malt extract.

The federal government’s grades for dried milk are: U.S. Premium, U.S. Extra, and U.S. Standard. You should use only the first two. U.S. Premium has a sweet flavor and is good for bakery production. U.S. Extra has a good flavor and aroma.

Creams

Bacterial count of cream should not be over 60,000 per ml and not more than 20 coli form per ml.

• Half and half. Equal parts of whole milk (3 ¼ percent milk fat) and cream (18 percent). It is about 10 ½ percent milk fat.

• Cultured half and half. In addition to standard half and half, it has 2 percent acidity.

• Table Cream. Has 18 to 20 percent milk fat.

• Sour Cream. Similar to table cream but has 2 percent acidity.

• Whipping Cream. Light (30 to 34 percent milk fat) or heavy (34 to 36 percent milk fat). It is not homogenized and is ripened three days before it is marketed.

• Filled Dairy Topping. 18 percent fat and contains milk solids, but the fat is not milk fat.

• Sour Cream Dressings. 16 to 18 percent milk fat with 2 to 5 percent acidity

Frozen Desserts

These frozen treats are pasteurized before they are frozen. The volume increase from whipping and freezing are: ice cream = 80 to 100 percent, sherbets = 40 percent, and ices = 25 percent. There are some states which forbid adding artificial flavors to frozen desserts.

Cheese

There is a wide variety of cheeses on the market. It is important for a restaurant manager to know the quality factors of cheese. Various types depend on the type of milk used, bacterial cultures, milk fat content, processing method, aging process, and more. Quality depends on the ingredients being used, the age, and storage method. The grades are AA, U.S. Extra Grade, and Quality Approved.

Various types of milk can be used to produce cheese including, whole, partially defatted, or nonfat milk. Annatto, a yellow or orange color, can be used in cheese without being noted on the label. The milk must be pasteurized or cured for 60 days; either technique is acceptable. Interestingly, about 100 pounds of milk make ten pounds of cheese.

Clabbered milk curd is used to produce cheese. When milk is pasteurized and cooled, a starter is added to the milk to create lactic acid and to sour the milk creating a firm curd. The curd is cut into cubes and cooked. The temperature influences the cheese product. A higher temperature creates a firmer and harder cheese. Cheddar is cooked below 100 degrees Fahrenheit and Swiss is cooked below 110 degrees Fahrenheit.

The curd is stirred to release whey and remove it from the mix, leaving a rubbery substance. The mix is poured into each side of the trough in which it is made and it can be cut after it solidifies. This process is called cheddaring. Other types of cheese besides cheddar are made this way. The strips are ground, salted, and piled into hoops. Specific mold or bacteria can be added at this point. When cheese is cured or aged, it undergoes a change of texture from rubbery to a softer, waxy mixture. The flavor becomes sharper and smoother. Various types of cheese are handled in different manners to create the individual tastes and textures that we love.

For information about cheese visit www.realcaliforniacheese.com, which provides recipes to use cheese and information about which wines to serve with cheese. You can find all these answers and much more by clicking on “World of Cheese.” This site is a great resource for any restaurant that serves cheeses. The information will be helpful when you experiment with recipes. You can e-mail them at ed@successfoods.com.

Hard Cheeses

There are many types of hard cheeses, but the most common are cheddar, American, Swiss, and Monterey jack.

Cheddar and American cheeses are the most common. Fine cheddars come from Oregon, Wisconsin, and New York. It is a hard cheese, cream to orange in color with a mild to sharp taste. The milk fat content must be below 50 percent and the moisture level below 39 percent. Grades are based on body, texture, aroma, taste, color, finish, and appearance. The grades for cheddar, curd cheddar, and Colby are AA (Extra), A (Standard), and B (Commercial). Aging is categorized with “current” (up to 60 days), “medium” (60 to 180 days), and “aged” (more than 180 days).

Swiss or emmental has a creamy, yellow, firm, smooth, sweet, nutty taste and large holes. Baby Swiss is the same but has smaller holes. This cheese is cooked at 125 to 130 degrees Fahrenheit to make it hard with a glossy appearance. The curing process for Swiss is tricky because the wrong humidity can cause mold or rinds. Federal grades for Swiss are AA, A, and B. The holes should be spaced and round or oval. Keep an eye out for sticky, dry cheese that is crumbly because the quality is poor. Swiss cheese becomes whiter as it ages. Aging is rated as “current” (60 to 90 days), “medium” (90 to 180 days), and “aged” (over 180 days).

Monterey Jack is creamy white, smooth, slightly firm, and mild flavored. It has 50 percent milk fat and is normally aged two to five weeks. Federal grades are AA, AS, and B. It has small holes and the surface is not shiny. Poor grades have large holes and a bitter taste.

Soft Cheeses

• Cottage or farm cheese is made by setting milk into a curd and cooking at 90 degrees Fahrenheit. The curd is cut, the whey removed, and 1 percent salt is added. The curd size is determined by the size of the knife used. If the moisture is below 70 percent, it can become dry.

• Ricotta Cheese is a soft cottage cheese which originated in Italy.

• Greek Feta is a soft curd cheese used in Greek, Balkan, and Arabic dishes. It has a sharp and delicate flavor and is crumbly. The curd can be served with butter and seasonings.

Specifications for Hard and Soft Cheeses

• Aging. The time needed to create a specific kind of cheese.

• Bacteria content. This information is not required for all cheeses.

• Fat Content. There are some designations that address the amount of fat – “non fat” and “low fat.”

• Flavor. Each kind of cheese has a distinctive flavor, but in some cases, spices, seasonings, or wines are added for a different flavor.

• Grade, Brand, and Quality. Only some cheeses have grades, but it is best to indicate the quality that you want.

• Kind. Use the common name for each item.

• Kind of Milk. Goat’s milk cheese would be an example of this standard.

• Moisture Content. There are maximum moisture contents for each cheese to classify the type of cheese; for example, hard, soft, moderately hard, and very hard.

• Origin. Sometimes includes the area where it originated and other times it could be the manufacturer.

• Size, Shape, or Packaging. Some may be distributed in normal shapes and sizes. An example would be cheddar which can come in large or small rounds, bricks, and other shapes.

Butter

The federal government says that butter should not contain more than 80 percent milk fat. It might contain salt and food coloring, but unsalted butter is on the market. It takes about 100 pounds of milk fat to produce 120 to 125 pounds of butter. After the milk is pasteurized, its acidity can be increased or decreased and Annatto can be added for coloring. After butter and buttermilk are created, the buttermilk is drained. Then the remaining butter is washed, salted, and worked. Working is necessary to get the right consistency. If it is overworked, the butter will become sticky and greasy. Butter is graded AA, A, B, and C. Scores are based on body, color, flavor, packaging, and salt. Aroma is considered flavor. The federal government’s standard for butter reads, “U.S. Grade of butter is determined on the basis of classifying first the flavor characteristics and then body, color, and salt. Flavor is the basic quality factor and is determined organoleptically by taste and smell.”

Margarine

The federal government states that margarine is made from one or more various approved vegetable or animal fats combined with cream. It may also contain vitamins A and D, butter, salt, artificial flavoring, colors, and preservatives. Labels must list any of these additional items. Beef fat used to be a favorite, but now soy oils are used more often than others. Some other oils include cottonseed, corn, other vegetable oils, or a blend of animal and vegetable oils.

Margarine is evaluated with the same standards as butter. The color, body, and texture should be consistent throughout the product. Flavors are clean, sweet, and free of unpleasant or unusual odors. You notice inconsistent colors and tastes when margarine is warm.