![]()

Chapter 15: Successful Kitchen Management and Control Procedures

This chapter on kitchen management is divided into three separate sections: personnel, procedures, and controls. HACCP and food-safety sanitation practices are covered in Chapter 16.

The personnel section describes the duties, functions, and responsibilities of the various employees that are found in any restaurant. Every restaurant is unique in the way it operates. Some adaptation of these positions may be necessary in meet your own restaurant’s needs. A list of specific job responsibilities provides details of some of the more critical positions.

The last part of the personnel section combines the functions into an organizational flowchart. This chart illustrates how kitchen employees unite their individual efforts and talents to present the final product to the customer.

The kitchen procedures section describes the basic day-to-day operational policies of the kitchen. Described are the procedures for purchasing, receiving, storing, rotating, and issuing all food items. Several sample forms are given at the end of this chapter, illustrating each of the procedures. These sample forms are also used in the control section and are an integral part of the control system.

Finally, the kitchen controls section combines all of the personnel and procedures previously described into a system of checks and balances. This section will enable the restaurant manager, through the use of the sample forms and simple procedures, to know exactly where every food item and every cent the restaurant business spent went.

The last few pages of this section consolidate all the personnel, procedures, and sample forms into a sequence of daily events to illustrate how every food item is controlled, from the initial purchasing stage to when the cashier rings up the sale.

Although Chapter 16 addresses HACCP food safety and sanitation, the kitchen controls section of this chapter describes basic sanitation practices with which every restaurant manager and every employee must be thoroughly familiar. This section is perhaps the most important. Improper handling of food items or disregarding sanitation procedures will undoubtedly lead to hazardous health conditions. There are numerous cases where restaurants have caused or were held responsible for the spread of severe sickness and infectious diseases that have even, in certain instances, led to death. There is no excuse for neglecting any health or sanitation procedure. It is the responsibility of the restaurant manager to guarantee the wholesomeness of the restaurant’s product.

KITCHEN PERSONNEL

THE KITCHEN DIRECTOR — JOB DESCRIPTION

A kitchen director, head cook, or head chef position can usually be found in any medium- to large-volume restaurant. Although job descriptions differ among various establishments, the primary objective of the kitchen director is to establish the maximum operational efficiency and food quality of the kitchen. The director is responsible for all the kitchen personnel and their training. Her foremost responsibility is to ensure that all food products are of the highest quality obtainable. She must set an example to other employees through her work habits and mannerisms. The restaurant manager must have complete faith in the ability of the kitchen director. The kitchen director must possess the same goals and desires as that of the restaurant’s manager: primarily a total dedication to serve only the finest food possible at the lowest cost.

Your kitchen director must be available during both the day and evening. During the day she must oversee the preparation cooks and ensure that all food products are ordered and accounted for. She would also be responsible for any breakfast, lunch, brunch, or catering functions. During the evening the director must make certain the kitchen is properly staffed and take any measures needed, including working in the kitchen behind the line to ensure positive results.

The restaurant manager cannot possibly spend the necessary time to supervise the kitchen and attend to all the minute details. Therefore it is highly recommended that a competent kitchen director be employed.

Kitchen Director’s Areas Of Responsibility

1. All personnel in the kitchen.

2. Food quality.

3. Controlling waste and food cost.

4. Ordering, receiving, storing, and issuing all food products.

5. Training of kitchen personnel.

6. Morale of the kitchen staff.

7. Health and safety regulation enforcement.

8. Communicating possible problem areas to the manager.

9. Scheduling all kitchen personnel.

10. Scheduling her own time.

11. Maintaining a clean and safe kitchen.

12. Holding kitchen staff meetings.

13. Filling out all forms for prescribed kitchen controls.

PREPARATION COOK — JOB DESCRIPTION

The preparation (“prep”) cook’s responsibility is to prepare all the food items in the restaurant in accordance with the preparation methods prescribed. The kitchen director trains, supervises, and is responsible for the preparation cooks. The preparation cooks are directly involved in determining the outcome and quality of the final food product. This area is where the greatest amount of waste occurs; the kitchen director must monitor preparation closely. Preparation cooks must follow the Recipe and Procedure Manual exactly as it is printed to ensure consistent products and food costs.

Some Responsibilities Of Preparation Cooks

1. Prepare all food products according to the prescribed methods.

2. Maintain the highest level of food quality obtainable.

3. Receive and store all products as prescribed.

4. Maintain a clean and safe kitchen.

5. Follow all health and safety regulations.

6. Follow all restaurant regulations.

7. Control waste.

8. Communicate all problems and ideas for improvement to management.

9. Communicate and work together with coworkers as a team.

10. Arrive on time and ready to work.

11. Attend all meetings.

12. Fill out all forms as prescribed.

13. Maintain all equipment and utensils.

14. Organize all areas of the kitchen.

15. Follow proper rotation procedures.

16. Label and date all products prepared. For resources visit www.daymarksafety.com or call 800-847-0101.

17. Follow management’s instructions and suggestions.

COOKING STAFF — JOB DESCRIPTION

The cooking staff arrives one to two hours before the restaurant is open for business. Their primary responsibility is to cook the prepared food items in the prescribed method. The cooking staff may be made up of regular line cooks or highly skilled chefs, depending on the complexity of the menu. They must ensure that all food products have been prepared correctly before cooking. They are the last quality-control check before the food is presented to the wait staff and the public. It is imperative that the cooking staff work together as a team and communicate with one another. A group effort is needed to keep the kitchen operating at maximum efficiency.

Some Responsibilities Of The Cooking Staff

1. Arrive on time and ready to work.

2. Ensure that proper preparation procedures have been completed.

3. Prepare the cooking areas for the shift.

4. Maintain the highest level of food quality obtainable.

5. Communicate with coworkers, wait staff, and management.

6. Become aware of what is happening in the dining room (arrival of a large group).

7. Account for every food item used.

8. Maintain a clean and safe kitchen.

9. Follow all health and safety regulations prescribed.

10. Follow all the restaurant regulations prescribed.

11. Control and limit waste.

12. Communicate problems and ideas to management.

13. Attend all meetings.

14. Fill out all forms required.

15. Maintain all kitchen equipment and utensils.

16. Keep every area of the kitchen clean and organized.

17. Follow the proper rotation procedures.

18. Label and date all products used. For resources visit www.daymarksafety.com or call 800-847-0101.

19. Follow management’s instructions and suggestions.

THE EXPEDITER — JOB DESCRIPTION

Sets the pace and flow in the kitchen. The expediter receives the order ticket from a waiter or waitress or from a printer in the kitchen and communicates which menu items need to be cooked to the cooking staff. Each cook performs a specific cooking function at his station, such as broiling, deep-frying, cooking pasta, sautéing, or carving. The expediter can regulate the pace in the kitchen by holding an order ticket for a few minutes before reading it to the cooking staff. Doing so is particularly useful when the cooks are bogged down in work.

The expediter is also responsible for laying out and garnishing all the plates. He makes certain that each member of the wait staff receives the correct plates with the correct items on them. As a double check, each wait staff member must check her order ticket against the actual prepared plates before taking them out of the kitchen. The expediter must make certain that every food item that leaves the kitchen has had an order ticket written for it. Under no circumstance is the expediter to instruct the cook to start the cooking of an item unless there is a written order ticket — it is crucial to the success of this control system. All order tickets are to be held by the expediter for reference at the end of the night.

Some Responsibilities Of The Expediter

1. Communicate with everyone in the kitchen.

2. Always get an order ticket from a waiter/waitress or kitchen printer.

3. Ensure all food leaving the kitchen is of the level of quality prescribed.

4. Make certain all plates are hot and garnished correctly.

5. Make certain that every food item is accounted for.

6. Safely store all food order tickets for later reference.

7. Fill out all required forms appropriately.

8. Maintain all equipment and utensils.

9. Keep own work area of the kitchen organized.

10. Follow all rotation procedures.

11. Label and date all products used. For resources visit www.daymarksafety.com or call 800-847-0101.

12. Follow management’s instructions and suggestions.

SALAD PREPARER — JOB DESCRIPTION

The salad preparer fixes and portions salads from the ingredients prepared during the day. A salad preparer is used when the restaurant has salad table service. For better control, this person may also be assigned to issue desserts. A salad preparer can be a great aid in speeding up service and controlling food cost.

Smaller restaurants that cannot justify the employment of a salad preparer should use the wait staff or cooks to prepare the salads. In this case, all dessert tickets must go to the expediter before the desserts are issued.

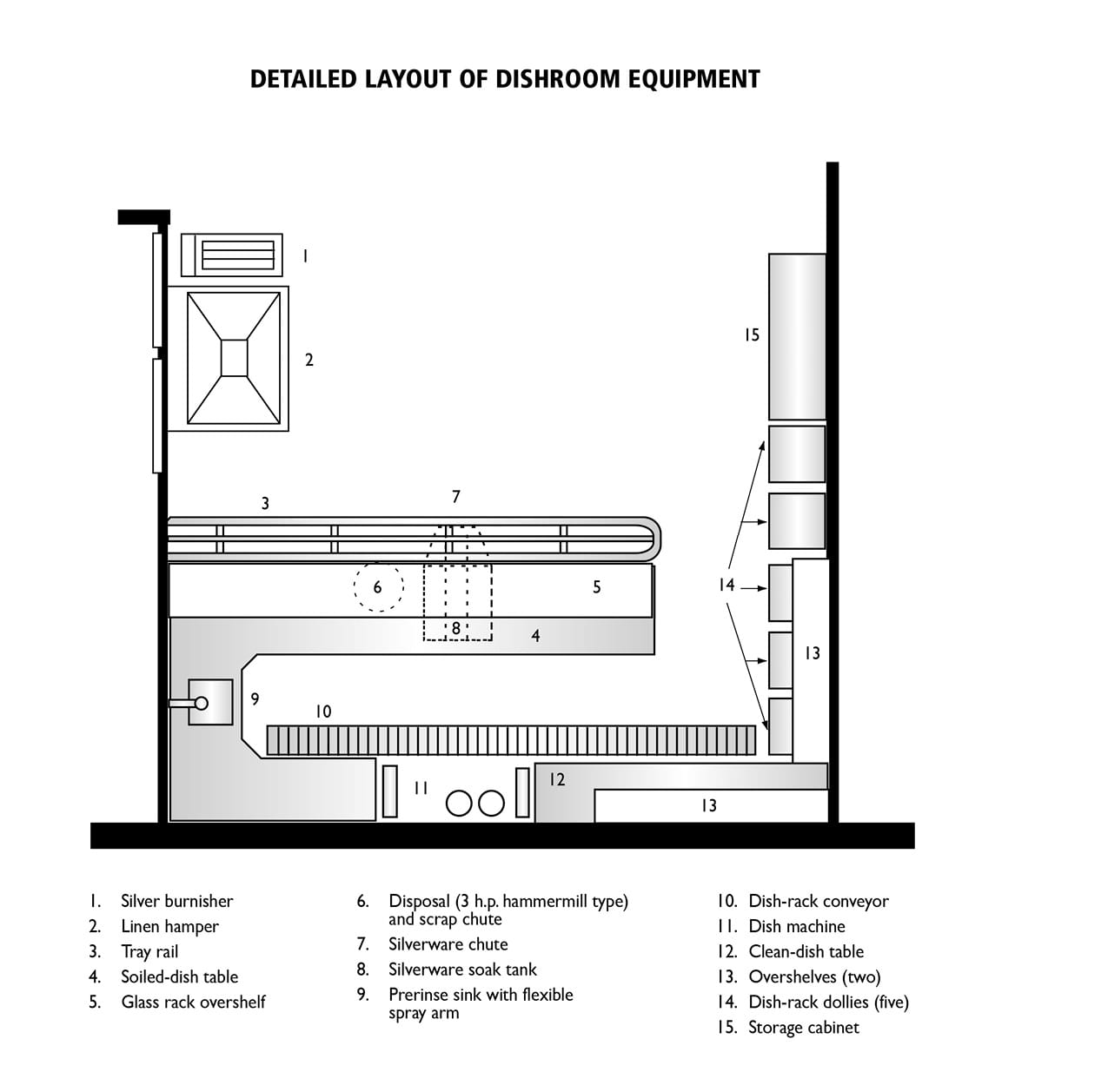

DISHWASHER — JOB DESCRIPTION

The dishwasher position is unfortunately often thought of as an unimportant position that anyone can be trained to perform quickly and cheaply. However, a dishwasher is as important as any other employee in the restaurant. She is responsible for supplying spotless, sanitized dishes to the dining room and clean kitchen utensils to the cooks. A slowdown in the dishwashing process will send repercussions throughout the restaurant. Improperly cleaned china, glassware, or flatware can ruin an otherwise enjoyable dining experience. How many times have you sat at a table with a dirty fork or a glass with lipstick residue? The dishwasher handles thousands of dollars of china and glassware every day. Accidentally dropping a tray of dishes can erase a day’s profits.

All glassware, china, flatware, and kitchen utensils have special washing requirements. The correct chemicals and dishwashing racks must be used in order to achieve the desired results. Your dishwasher chemical company can supply you with all the training. Your salesperson can set up a training session with your staff. He will instruct your staff on how to operate the dishwasher correctly, set up systems to alleviate breakage, use the chemicals correctly, and set up the proper daily maintenance needed on the machine.

KITCHEN PROCEDURES

PURCHASING

The goal of purchasing is to supply the restaurant with the best goods at the lowest possible cost. There are many ways to achieve lowest possible cost. The buyer must have favorable working relations with all suppliers and vendors. A large amount of time must be spent meeting with prospective sales representatives and companies. The buyer’s responsibility is to evaluate and decide how to best make each of the purchases for the restaurant. Purchasing is a complex area that must be managed by someone who is completely familiar with all of the restaurant’s needs. The kitchen director or manager would be the best choice to do the purchasing. It is preferable to have one or two people do all the purchasing for all areas of the restaurant. There are several advantages to this, such as greater buying power and better overall control.

Provided the buyer completes the necessary research and evaluates all of the possible purchasing options, she can easily recoup a large part of her salary from the savings made. The most critical element to grasp when purchasing is the overall picture. Price is not the top priority and is only one of the considerations in deciding how and where to place an order.

INVENTORY LEVELS

The first step in computing what item and how much of it to order is to determine the inventory level, or the amount needed on hand at all times. It is a simple procedure and requires that the order sheets are prepared properly. To determine the amount you need to order, you must first know the amount you have in inventory. Walk through the storage areas and mark in the “On Hand” column the amounts that are there. To determine the “Build-To Amount,” you will need to know when regularly scheduled deliveries arrive for that item and the amount used in the period between deliveries. Add on about 25 percent to the average amount used; this will cover unexpected usage, a late delivery, or a backorder at the vendor. The amount you need to order is the difference between the Build-To Amount and the amount On Hand. Experience and food demand will reveal the amount an average order should contain. By purchasing too little, the restaurant may run out of supplies before the next delivery. Ordering too much will result in tying up money, putting a drain on the restaurant’s cash flow. Buying up items in large amounts can save money, but you must consider the cash-flow costs. A buying schedule should be set up and adhered to. This schedule would consist of a calendar showing:

• Which day’s orders need to be placed.

• When deliveries will be arriving.

• What items will be arriving from which company and when.

• Phone numbers of sales representatives to contact for each company.

• The price the sales representative quoted.

Post the buying schedule on the office wall. When a delivery does not arrive as scheduled, the buyer should place a phone call to the salesperson or company immediately. Do not wait until the end of the day when offices are closed.

A “Want Sheet” (see the example at the end of this chapter) may be placed on a clipboard in the kitchen. This sheet is made available for employees to write in any items they may need to do their jobs more efficiently. It is a very effective form of communication; employees should be encouraged to use it. The buyer should consult this sheet every day. A request might be as simple as a commercial-grade carrot peeler.

COOPERATIVE PURCHASING

Many restaurants have formed cooperative purchasing groups to increase their purchasing power. Many items are commonly used by all food service operators. By cooperatively joining together to place large orders, restaurants can usually get substantial price reductions. Some organizations even purchase their own trucks and warehouses and hire personnel to pick up deliveries. Doing so can be quite advantageous for restaurants that are in the proximity of a major supplier or shipping center. Many items, such as produce, dairy products, seafood, and meat, may be purchased this way. Chain-restaurant organizations have a centralized purchasing department and, often, large self-distribution centers.

RECEIVING AND STORING

Most deliveries will be arriving at the restaurant during the day. The preparation crew is normally responsible for receiving and storing all items (excluding liquor, beer, and wine). The buyer should also be present to ensure that each item is of the specification ordered.

Receiving and storing each product is a critical responsibility. Costly mistakes can come about from a staff member who was not properly trained in the correct procedures. Listed below are some policies and procedures for receiving and storing all deliveries. A slight inaccuracy in an invoice or improper storing of a perishable item could cost the restaurant hundreds of dollars.

Watch for a common area of internal theft. Collusion could develop between the delivery person and the employee receiving the products. Items checked as being received and accounted for may not have been delivered at all. The driver simply keeps the items. In an upcoming section I will discuss how to guard against internal theft.

All products delivered to the restaurant must:

1. Be checked against the actual order sheet.

2. Be the exact specification ordered (weight, size, quantity).

3. Be checked against the invoice.

4. Be accompanied by an invoice containing: current price, totals, date, company name, and receiver’s signature.

5. Have their individual weights verified on the pound scale.

6. Be dated, rotated, and put in the proper storage area immediately. For resources visit www.daymarksafety.com or call 800-847-0101.

7. Be locked in their storage areas securely.

Credit slips must be issued or prices subtracted from the invoice when an error occurs. The delivery person must sign over the correction.

Keep an invoice box (a small mailbox) in the kitchen to store all invoices and packing slips received during the day. Mount the box on the wall, away from work areas. Prior to leaving for the day, the receiver must bring the invoices to the manager’s office and place them in a designated spot. Extreme care must be taken to ensure that all invoices are handled correctly. A missing invoice will throw off the bookkeeping and financial records and statements.

ROTATION PROCEDURES

1. New items go to the back and on the bottom.

2. Older items move to the front and to the left.

3. In any part of the restaurant: the first item used should always be the oldest.

4. Date and label everything.

DayMark Safety Systems has offers a wide variety of labeling and food safety products. Their DissolveMark™ labels dissolve in 30 seconds and will not leave any sticky residue which can harbor harmful bacteria. The MoveMark™ labels with glow-in-the-dark technology perfect for dimly lit areas. They are FDA approved for indirect food contact. Standard MoveMark labels remove easily from plastic and metal containers. DuraMark™ permanent labels have aggressive adhesive that is moisture resistant and adheres to any surface. CoolMark™ labels are designed exclusively the freezer and are available in both hand-applied and machine-applied labels. To view DayMark’s complete product line, visit www.daymarksafety.com or call 800-847-0101.

|

TEMPERATURE RANGES FOR PERISHABLE ITEMS |

|

|

All frozen items |

-10–0˚ F |

|

Fresh meat and poultry |

31–35˚ F |

|

Produce |

33–38˚ F |

|

Fresh seafood |

33–38˚ F |

|

Dairy products |

33–38˚ F |

|

Beer |

40–60˚ F |

|

Wine (Chablis, rosé) |

45–55˚ F |

|

Wine (most reds) |

55–65˚ F |

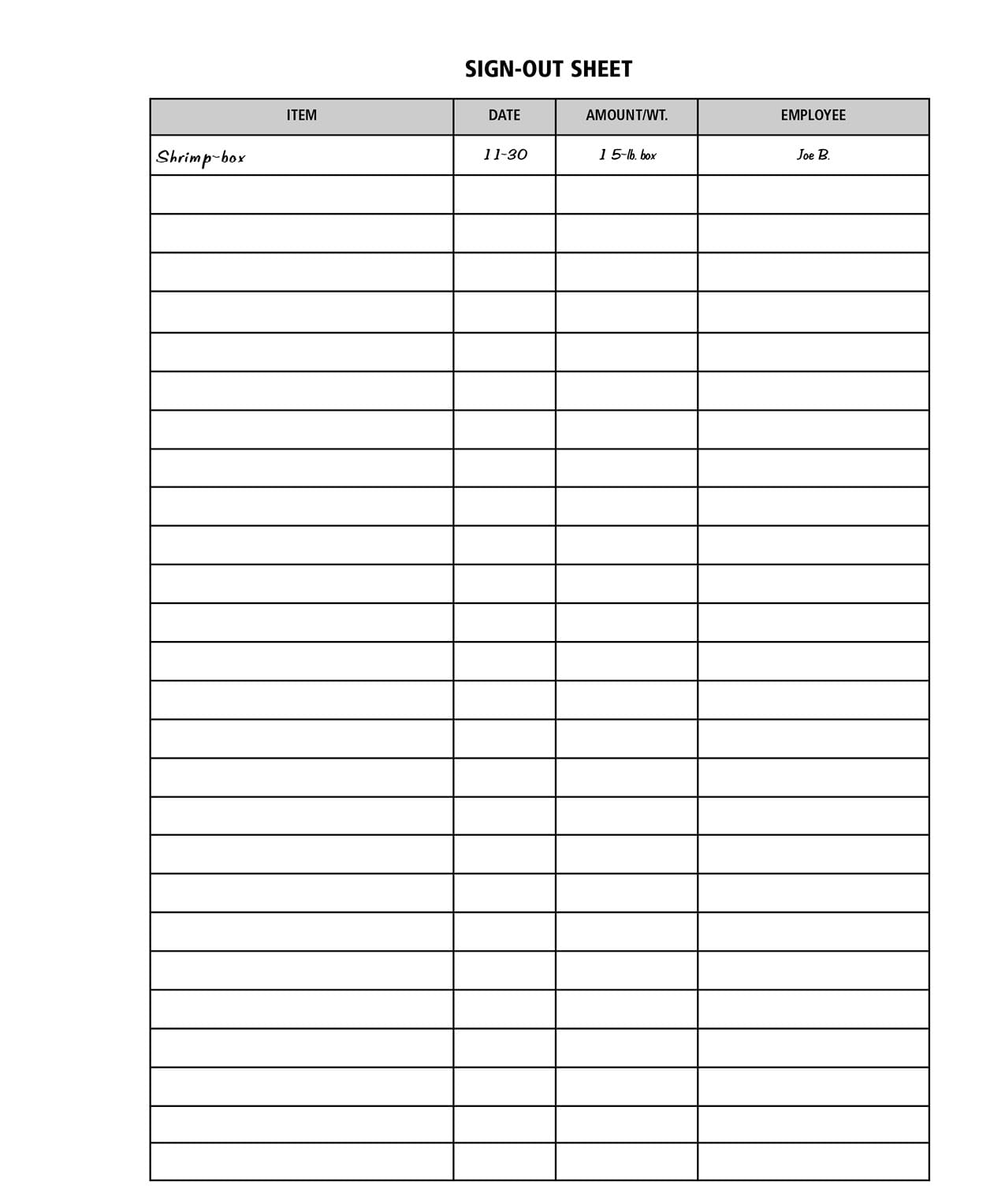

ISSUING

All raw materials from which portionable entrees are prepared, such as meat, seafood, and poultry, must be issued on a daily basis. Whenever one of these bulk items is removed from a freezer or walk-in, it must be signed out. An example of a Sign Out Sheet may be found at the end of this chapter. When a part of a case or box is removed, the weight of the portion removed must be recorded in the “Amount” column. The Sign Out Sheet should be on a clipboard affixed to the walk-in or freezer. Once the item is signed out, the weight must be placed in the “Amount Ordered or Defrosted” column on the Preparation Form. An example of a Preparation Form may be found at the end of this chapter. This will show that the items signed out were actually used in the restaurant. From this information, the kitchen director can compute a daily yield on each item prepared. This yield will show that the portions were weighed out accurately and the bulk product that was used to prepare menu items. At any one of these steps pilferage can occur. The signing-out procedure will eliminate pilferage. Products such as dry goods or cleaning supplies may be issued in a similar manner. If these or other items were being stolen, the cost of each would show up in the cost projections at the end of the month.

KITCHEN CLEANLINESS

Kitchen cleanliness must always be of constant concern to both management and employees. A maintenance company should do little cleaning in the kitchen. They have not been trained in the cleaning procedures that must be used in the kitchen to maintain food safety requirements. A maintenance company should only be used for cleaning and washing the kitchen floor. The rest of the kitchen cleaning and maintenance is the responsibility of the staff.

All employees must be made aware that their daily cleanups are as critical as any of their other responsibilities — perhaps more so. A complete section on food safety can be found in the next chapter. Every employee must be completely familiar with its contents.

The most effective cleanup policy to institute is to make each employee responsible for his own area. Every workstation must have its own cleaning check-off sheet for the end of each shift. (See the example on the next page.) These sheets should be sealed in plastic, so that a grease pencil can be used to check off each completed item. Every employee must have his cleanup checked by a manager. You must inspect employee cleanup carefully and thoroughly. Once a precedent is set for each cleanup it must be maintained. At the end of a long shift some employees may need a little prodding to get the desired results.

|

CLEAN-UP SHEET FOR EACH COOK |

|

|

Place a check mark on all completed items. ___1. Turn off all equipment and pilots. ___2. Take all pots, pans, and utensils to the dishwasher. ___3. Wrap, date, and rotate all leftover food. ___4. Clean out the refrigerator units. ___5. Clean all shelves. ___6. Wipe down all walls. ___7. Spot clean the exhaust hoods. ___8. Clean and polish all stainless steel in your area. ___9. Clean out all sinks. ___10. Take out all trash. Break down boxes to conserve space in dumpster. ___11. Sweep the floor in your area. ___12. Replace all clean pots, pans, and utensils. ___13. Check to see if your coworkers need assistance. ___14. Check out with the manager. |

|

|

COOK |

TIME OF LEAVING |

|

MANAGER |

|

KITCHEN CONTROLS

The following section will present a system of kitchen controls. Combining these controls with the procedures and policies already set forth will enable you to establish an airtight food cost control system. The key to controlling food cost is reconciliation. Every step or action taken is checked and reconciled with another person. Management’s responsibility is to monitor them with daily involvement. Should all the steps and procedures be adhered to, you will know exactly where every dollar and ounce of food went. There are no loopholes. Management must be involved in the training and supervision of all employees. Daily involvement and communication is needed in order to succeed. Employees must follow all procedures precisely. If they do not, they must be informed of their specific deviations from these procedures and correct them. Any control initiated is only as good as the manager who follows up and enforces it. The total amount of time a manager needs to complete all of the work that will be described in this section is less than one hour a day. There is no excuse for not completing each procedure every day. A deviation in your controls or involvement can only lead to a loss over the control of the restaurant’s costs. Please note: Although a simple manual system is detailed here, many of these functions can be implemented into your computerized accounting system. Many of the basic purchasing and receiving functions are found in virtually all off-the-shelf accounting programs.

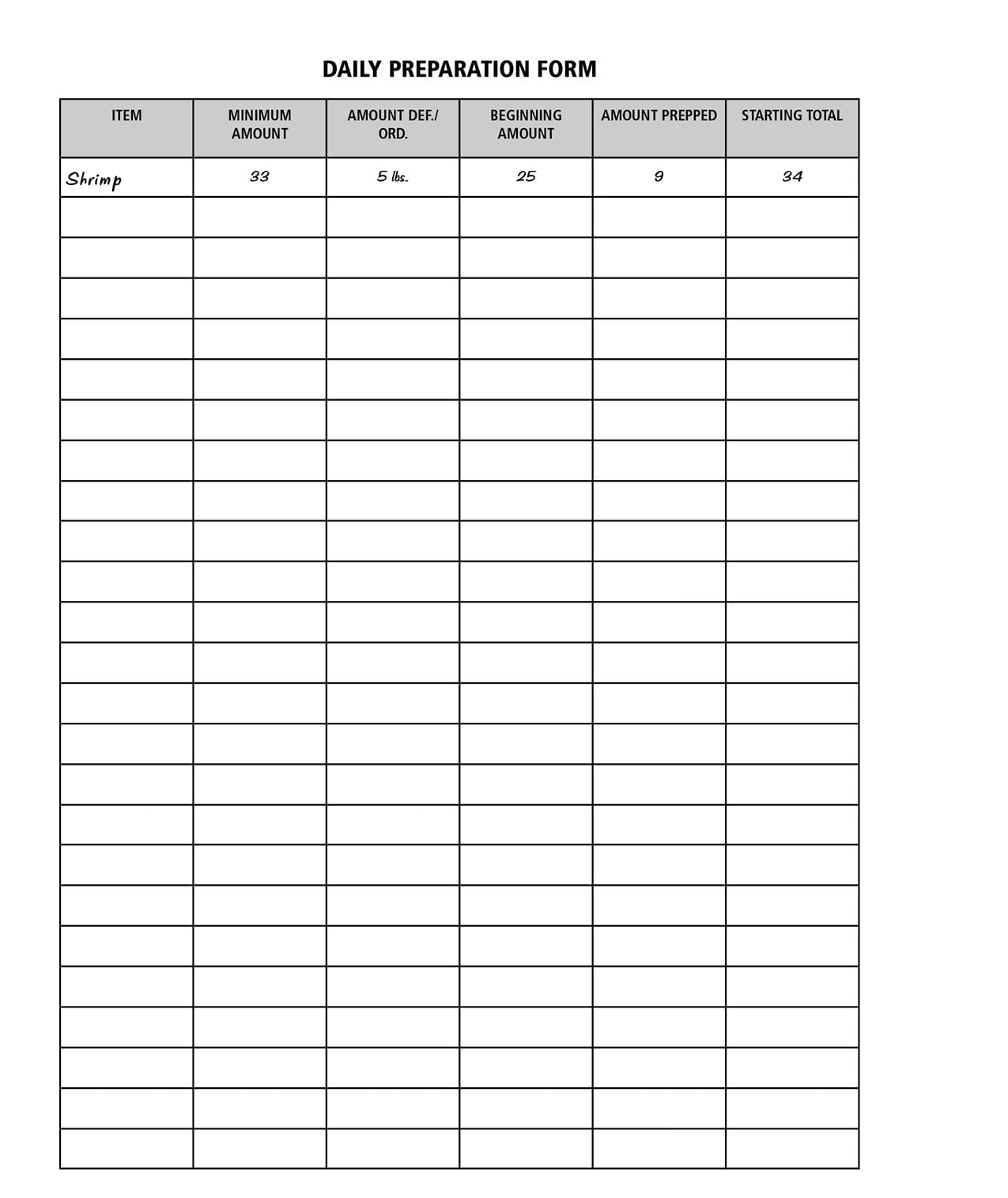

PREPARATION FORM

The Preparation Form is used by the preparation cooks. See the example form at the end of this chapter. It should be filled out as follows:

A. The first procedure performed each morning by the preparation cook is counting the number of items on hand. These are food items left from the previous night. The number of each item left is placed in the “Beginning Amount” column. Every item that needs to be prepared must be on this sheet: all entrees, side orders, desserts, salad items. This sheet will be used as a reference guide throughout the day to determine which items need to be prepared.

B. List the minimum amount needed for the day from the Minimum Amount Needed Form. This form sets the minimum amount you need to have prepared for the cooking staff. Each day will show a different amount, depending upon the amount of customers you anticipate serving. The minimum amount needed is computed by management based on the number of items previously sold on an average day in the past. Procedures for calculating the Minimum Amount Needed are discussed in the following section.

C. Subtract the Beginning Amount from the Minimum Amount Needed. This figure will be the amount that needs to be prepared for that particular item. Based on this figure you can then compute the amount of food that must be either ordered or removed from the freezer to defrost. All portion-controlled items must be signed out on the Sign Out Sheet before being removed from the freezer or walk-in.

D. All items entered on the Sign Out Sheet must also be entered in the “Amount Ordered or Defrosted” column on the Preparation Form. This information is entered here so that the kitchen director will be able to compute a yield on all the items prepared. This column will also be used by the manager to calculate the daily perpetual inventory, which will be discussed later in this chapter.

E. As the day progresses, items will be prepared, dated, wrapped, rotated, and placed in the walk-in for use that night. The number of portions prepared for each item is recorded in the “Amount Prepared” column.

F. The Amount Prepared plus the Beginning Amount equals the starting total. The starting total must be equal to or greater than the minimum amount needed. When all items are completed, the preparation sheet is placed in the manager’s office.

MINIMUM AMOUNT NEEDED FORM

The purpose of the Minimum Amount Needed Form is to guide the preparation cook in determining the amount of food that will need to be prepared for each day. An example of the Minimum Amount Needed Form can be found at the end of this chapter. The Minimum Amount Needed must be large enough so that the restaurant will not run out of any food during the next shift. However, too much prepared food will quickly lose its freshness and may spoil altogether.

To compute the Minimum Amount Needed of each item for each particular day, consult the Food Itemization Form, described in Chapter 35, “Internal Bookkeeping.” This form will list the actual number of each menu item sold for every day of the past month. It will also indicate the percentage sold of that item in relation to the rest of the menu items for the month and for each day. Examine the last two months’ product mixture figures. Based on this information you should get a relatively accurate depiction of the amount of each item sold on each particular day of the week. Based on the average amount sold each day and the percentage sold in relation to the total menu, you will be able to project the minimum amount needed for the following months.

Example

According to the Food Itemization Form last month the restaurant sold between 20 and 25 shrimp dinners each Saturday night. The restaurant served between 200 and 300 dinners for each of these nights, so about 10 percent of the menu selections sold were shrimp dinners. To project next month’s Minimum Amount Needed for an average Saturday evening, estimate the average number of dinners you expect to serve.

Let us assume 250 dinners will be sold on an average Saturday evening. Multiply this figure (250) by the average percentage of the menu sold (10 percent, or .10) — the answer (25) would be the approximate number of shrimp dinners you would sell on an average Saturday for the next month. It is only an educated guess; add 30 percent to the figure you projected to cover a busy night. In the example, this extra 30 percent is eight more dinners: 33 shrimp dinners is the minimum amount needed for Saturday night. Holidays and seasonal business changes need to be considered when setting minimum amounts.

DAILY YIELDS

Daily yields represent the actual usage of a product from its raw purchased form to the prepared menu item. The yield percentage is a measure of how efficiently this was accomplished or how effectively a preparation cook eliminated waste. The higher the yield percentage, the more usable material was obtained from that product.

All meat, seafood, and poultry products must have a yield percentage computed for each entree every day. Yields are extremely important when determining menu prices. They are also a very useful tool in controlling food cost. Daily yields should be computed by the kitchen director. An example of a Daily Yield Sheet can be found at the end of this chapter.

Yield sheets should be kept for several months: They may become useful in analyzing other problem areas. All the information to compute each yield can be obtained from the Daily Preparation Form.

To Compute The Yield Percentage:

1. From the “Amount Ordered or Defrosted” column compute the total amount of ounces used. Verify the amount in this column against the Sign Out Sheet. This figure is the starting weight in ounces.

2. The ”Amount Prepared“ column contains the number of portions yielded. Enter this figure on the Yield Sheet.

3. To compute the yield percentage, divide the Total Portion Weight (in ounces) by the Total Starting Weight (in ounces).

Yields should be consistent regardless of who prepares the item. If there is a substantial variance in the yield percentages — 4 to 10 percent — consider these questions:

1. Are the preparation cooks carefully portioning all products? Over the months have they gotten lax in these methods?

2. Are you purchasing the same brands of the product? Different brands may have different yields.

3. Are all the items signed out on the Sign Out Sheet actually being used in preparing the menu items? Is it possible some of the product is being stolen after it is issued and before it is prepared? Do certain employees preparing the food items have consistently lower yields than others?

4. Is the staff properly trained in cutting, trimming, and butchering the raw products? Do they know all the points of eliminating waste?

Periodically compare the average yield percentage to the percentage used in projecting the menu costs. If the average yield has dropped, you may need to review the menu prices.

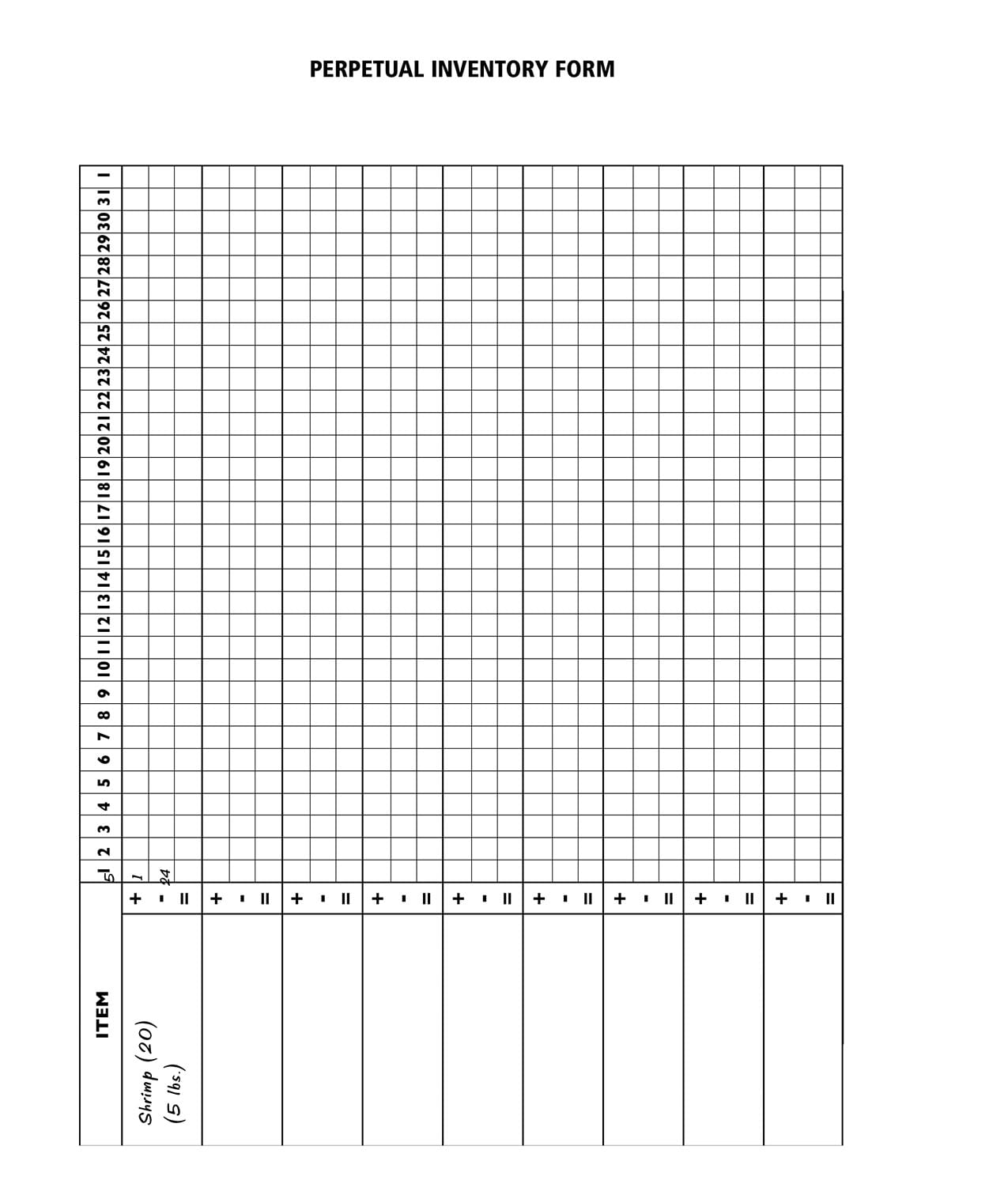

PERPETUAL INVENTORY

The perpetual inventory is a check on the daily usage of items from the freezers and walk-ins. This form is used in conjunction with the Sign Out Sheet. An example of the Perpetual Inventory Form may be found at the end of this chapter. When completed, the perpetual inventory will ensure that no bulk products have been stolen from the freezer or walk-ins. List all the food items that are listed on the Sign Out Sheet and Yield Sheet. In the “Size” column list the unit size that the item is packaged in. The contents of most cases of food are packed in units such as five pound boxes or two pound bags. Meat is usually packed by the number of pieces in a case and the case’s weight. The size listed on the perpetual inventory must correspond to the size the preparation cooks are signing out of the freezer and walk-ins.

In the “Start” column, enter the number of each item listed. For example, if shrimp is packed in five pound boxes and you have two 50-pound cases, there are 20 boxes. Enter 20 in the “Start” column. Each number along the top corresponds to each day of the month. At the end of each day, count all the items on hand and enter this figure on the “=” line. Compare this figure to the “Amount Ordered or Defrosted” column on the Preparation Form; these amounts must be the same. Place the total number of each item on the “–” line. If there were any deliveries, place this total on the “+” line.

Check the invoices every day for the items delivered that are in your perpetual inventory. Ensure that all items signed off as being delivered are actually in the storage areas. Should there be a discrepancy, check with the employee that signed the invoice. The number of items you start with (20) plus the number you received in deliveries (five), minus the amount signed out by the preparation cooks (one), must equal the number on hand (24). If there is a discrepancy, you may have a thief.

Should you suspect a theft in the restaurant, record the names of all employees who worked that particular day. If thefts continue to occur, a pattern will develop among the employees who were working on all the days in question. Compute the perpetual inventory or other controls you are having a problem with at different times of the day, before and after each shift. Doing so will pinpoint the area and shift in which the theft is occurring. Sometimes placing a notice to all employees that you are aware of a theft problem in the restaurant will resolve the problem. Make it clear that any employee caught stealing will be terminated.

GUEST TICKETS AND THE CASHIER

There are various methods of controlling cash and guest tickets. The following section will describe an airtight system of checks and balances for controlling cash, tickets, and prepared food. Certain modifications may be needed to implement these controls in your own restaurant. Many of the cash registers and POS systems available on the market can eliminate most of the manual work and calculations. The systems described in this section are based on the simplest and least expensive cash register available. The register must have three separate subtotal keys for food, liquor and wine sales, and a grand-total key for the total guest check. Sales tax is then computed on this amount. The register used must also calculate the food, liquor, and wine totals for the shift. These are basic functions that most machines have. Guest tickets must be of the type that is divided into two parts. The first section is the heavy paper part listing the menu items. At the bottom is a space for the subtotals, grand total, tax, and a tear-away customer receipt. The second section is a carbon copy of the first. The carbon copy is given to the expediter, who then issues it to the cooks, who start the cooking process. Some restaurants utilize handheld ordering computers and/or the tickets may be printed in the kitchen at the time of entry into the POS system or register. Regardless, the expediter must receive a ticket in order to issue any food.

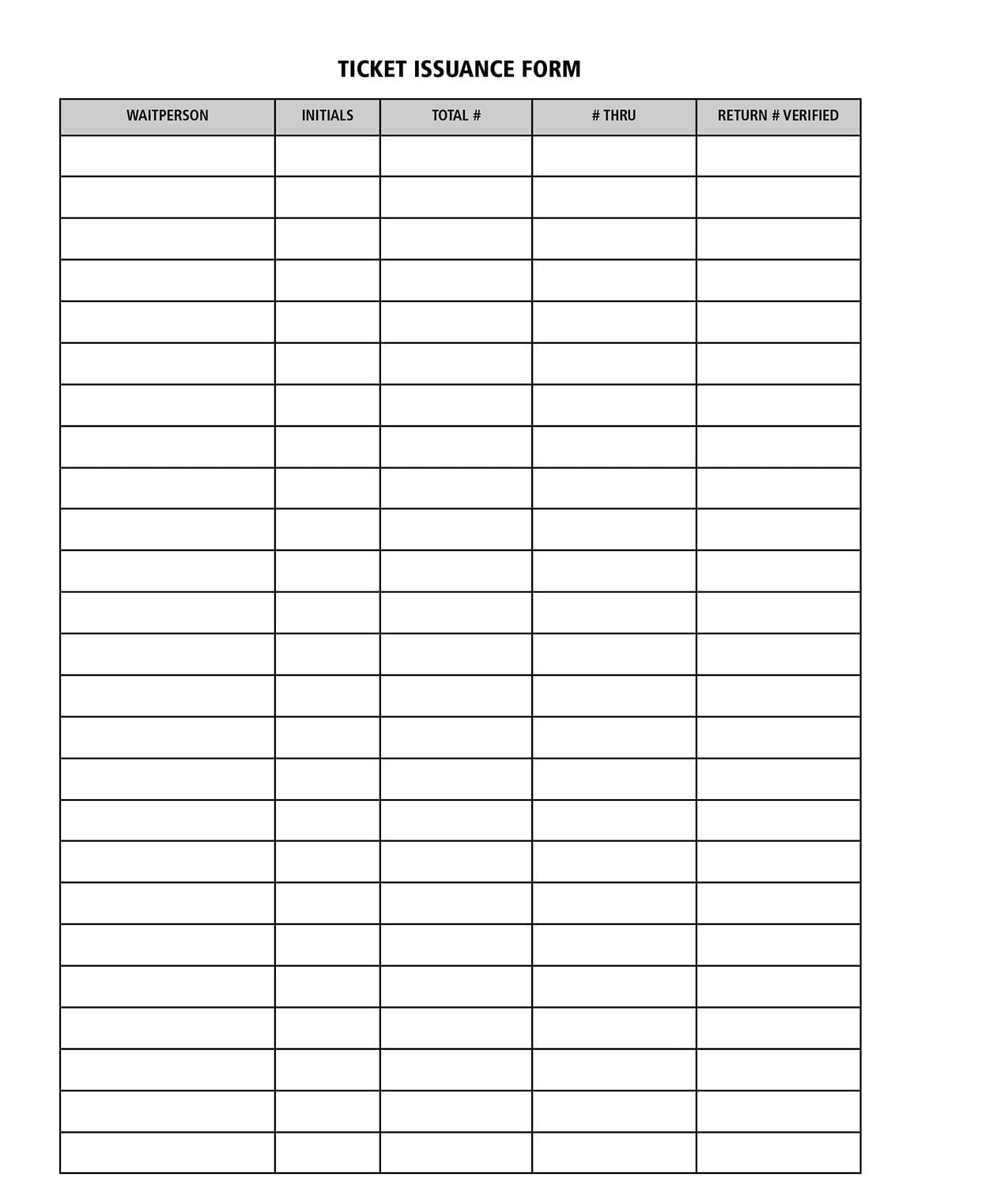

The tickets must have individual identification numbers printed in sequence on both parts and the tear-away receipt. They must also have a space for the waitperson’s name, the date, table number, and the number of people at the table. This information will be used by the expediter and bookkeeper in tracking down lost tickets and/or food items. Each member of the wait staff is issued a certain number of tickets each shift. These tickets are in numbered sequence.

For example, a waiter may be issued 25 tickets from 007575 to 007600. At the end of the shift he must return to the cashier the same total number of tickets. No ticket should ever become lost; it is the responsibility of the wait staff to ensure this. Should there be a mistake on a ticket, the cashier must void out all parts. This ticket must be turned in with the others after being approved and signed by the manager. The manager should issue tickets to each individual waiter and waitress. An example of a Ticket Issuance Form can be found at the end of this chapter. In certain instances, the manager may approve of giving away menu items at no charge. The manager must also approve of the discarding of food that cannot be served. A ticket must be written to record all of these transactions. Listed below are some examples of these types of situations:

• Manager food. All food that is issued free of charge to managers, owners, and officers of the company.

• Complimentary food. All food issued to a customer compliments of the restaurant. This includes all food given away as part of a promotional campaign.

• Housed food. All food that is not servable, such as spoiled, burned, or incorrect orders.

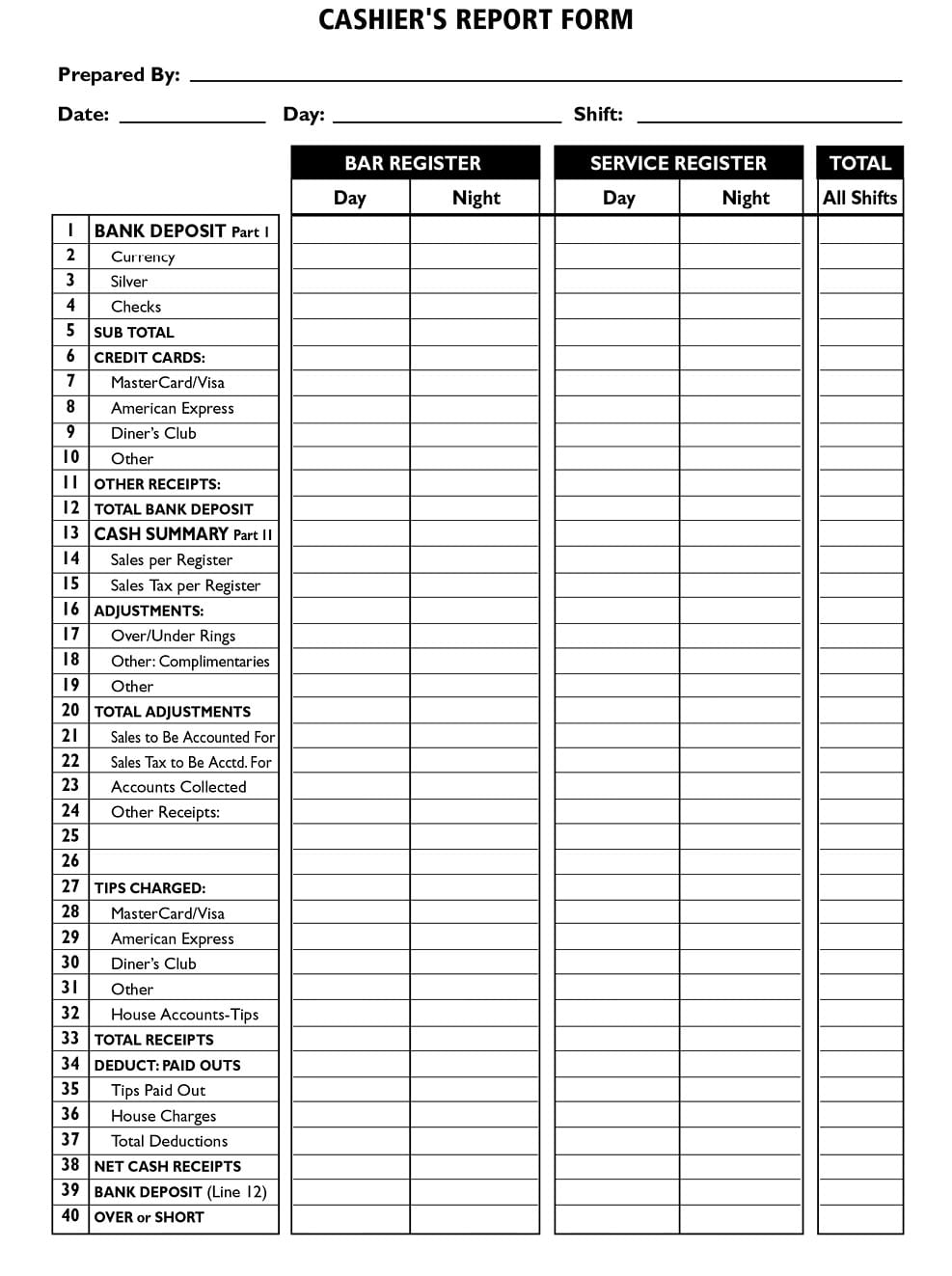

All of these tickets should be filled out as usual, listing the items and the prices. The cashier should not ring up these tickets, but record them on the Cashier’s Report Form. Write the word “manager,” “complimentary,” or “housed” over the top of the ticket.

The manager issues cash drawers, or “bank,” to the cashier. The drawers are prepared by the bookkeeper. Inside the cashier drawer is the Cashier’s Report itemizing the breakdown of the money it contains. An example of the Cashier’s Report Form can be found at the end of this chapter. The accuracy of the Cashier’s Report is the responsibility of both the cashier and the manager. Upon receiving the cash drawer, the cashier must count the money in the cash drawer with the manager to verify its contents. After verification, the cashier will be responsible for the cash register. The cashier should be the only employee allowed to operate it. Each member of the wait staff will bring his or her guest ticket to the cashier for totaling.

The cashier must examine the ticket to ensure:

• All items were charged for.

• All items have the correct price.

• All the bar and wine tabs are included.

• Subtotals and grand total are correct.

• Sales tax is entered correctly.

The cashier is responsible for filling out the charge-card forms and ensuring their accuracy. The cashier will return the customer’s charge card and receipt to the appropriate member of the wait staff.

At the end of each shift, the cashier must cash out with the manager. List all the cash in the “Cash Out” columns. Enter the breakdown of sales into separate categories. Do not include sales tax. Enter all complimentary, housed, and manager amounts. Itemize all checks on the back. Itemize each ticket for total sales and total dinner count. Break down and enter all charged sales.

The total amount of cash taken in plus the charge sales must equal the total itemized ticket sales. Itemize all checks on the back of the Cashier’s Report and stamp “FOR DEPOSIT ONLY:” the stamp should include the restaurant’s bank name and account number.

Should a customer charge a tip, you may give the waiter or waitress a “cash paid out” from the register. When the payment comes in you can then deposit the whole amount into your account. Miscellaneous paid-outs are for any items that may need to be purchased throughout the shift. List all of them on the back and staple the receipts to the page.

When everything is checked out and balanced, the sheet must be signed by the cashier and manager. The manager should then deposit all tickets, register tapes, cash, charges, and forms into the safe for the bookkeeper the next morning. The cash on hand must equal the register receipt readings.

COOK’S FORM

The Cook’s Form is used in conjunction with the Preparation Form. When both of these forms are completed, you will have complete accountability for all menu items. An example of the Cook’s Form can be found at the end of this chapter. In the “Item” column list all the entrees, side orders, and desserts. These items should be in the same sequence as in the Preparation Form for ease of comparison. In the “Start” column list all the items that were left over from the day before. Look at the dates to ensure that all the items used first are the oldest.

The “Additions” column contains the items that were prepared that day. The “Starting Balance” column contains the total of the Start amount plus the Additions. This figure represents the total number of starting items for the shift.

At the beginning of each cook’s shift, the manager will compare the total starting figure on the Cook’s Form to the total starting figures on the Preparation Form. All numbers must match. If any of the items do not match, the cook must go back and recount that item. You must be certain that both the Cook’s Form and the Preparation Form are accurate. Recount the items yourself if necessary. Should there still be a discrepancy, you must consider whether there has been a theft sometime after the preparation cooks finished and before the cooking staff completed their form.

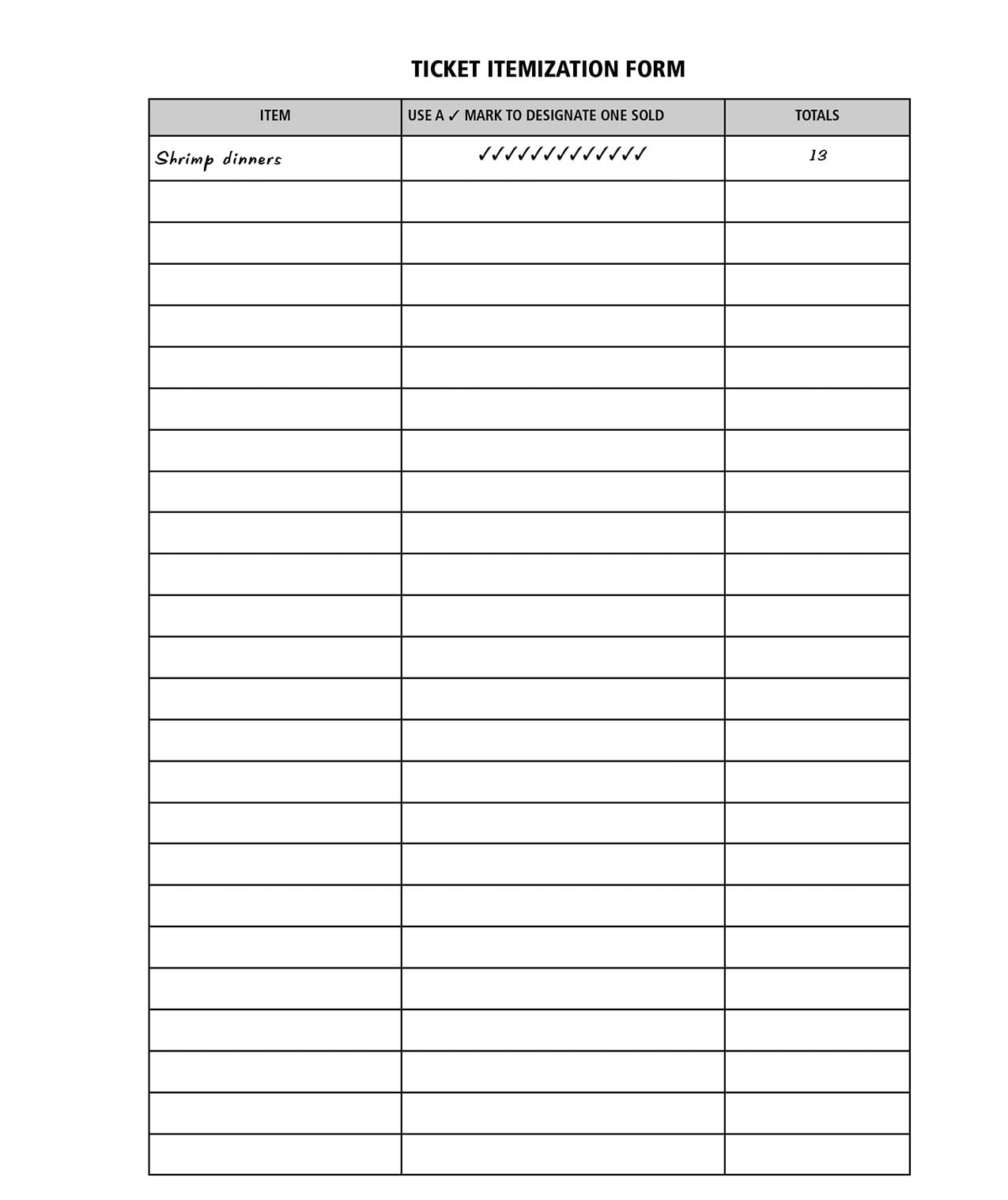

When the cooking shift is completed, the cooks will recount all the items not used. These figures are placed in the “Balance Ending” column. The difference between the Starting and the Balance Ending is the number sold. Once completed, the cooks will turn the sheet over to the expediter. The expediter will verify that the number of items sold equals the number of items cooked. To compare these two figures he must itemize the carbon copy part of the tickets that were given to him by the wait staff. An example of this Ticket Itemization Form can be found at the end of this chapter.

To itemize the tickets, place an “X” in the column next to the corresponding item. The total number of “X” marks equals the total number of tickets received for that item. Enter this figure in the “# Sold” column. The Total Sold from the Ticket Itemization Form must equal the total amount sold on the Cook’s and Cashier’s Report Forms. If there is a discrepancy:

• The expediter must re-itemize all tickets.

• The cooks must recount the ending balance.

• Make certain you considered all house, complimentary, and manager tickets.

Should there still be a discrepancy, the manager must recheck all the calculations and make certain all the tickets are accounted for. If the differences remain unresolved, you must consider that theft may be the reason. Either the item left the kitchen without a ticket or the item was taken without the cooking staff realizing it. The latter is unlikely, since the cooks are usually at their stations for the entire shift.

Once the Cook’s Form is reconciled, return it to the office. All the Preparation, Cook’s, and Ticket Itemization Forms should be kept in a loose-leaf binder for several weeks for reference.

Each morning the manager will compare the cook’s Balance Ending figure with the preparation cook’s Beginning Amount. Doing so will verify that all the items from last night are still there the following morning. This completes the daily cycle of checks and balances. The bookkeeper will further break down and analyze the forms, cash, and tickets.

SUMMARY

To enable you to envision precisely how the personnel procedures and controls combine to control the restaurant’s food cost, a summary of the key points are listed in this section in sequence of events. In the example you will trace 25 pounds of shrimp through a typical day’s operation, from the initial purchasing to the final product. The first column in each of the example forms are filled out so you will be able to see how they are used and why each one is a critical part in the overall control system. I would recommend that the manager put the following list in the form of a check-off sheet for his own organizational purposes.

SEQUENCE OF EVENTS

___1. Determine the need to purchase shrimp.

___2. Purchase the amount needed. An example: 25 pounds.

___3. Shrimp is delivered. Follow the receiving and storing procedures.

___4. Enter on the Perpetual Inventory Form the amount delivered. In example: five boxes of five pounds each.

___5. Preparation cooks compute the opening counts. In example: 25 shrimp dinners is the beginning count.

___6. Determine the Minimum Amount Needed: 33. The preparation cooks need to prepare eight more dinners for that night. They remove five pounds, or one box, of shrimp from the freezer.

___7. Sign out the five pounds of shrimp on the Sign Out Sheet.

___8. Place the amount, five pounds, in the ”Amount Ordered or Defrosted“ column on the Preparation Form.

___9. Prepare the shrimp as prescribed in the Recipe and Procedure Manual.

___10. The number of dinners prepared is nine; enter this figure in the ”Amount Prepared“ column. The starting total would be 34 (9 + 25). Enter these figures on the Preparation Form.

___11. The Preparation Form is completed and given to the kitchen director. All storage areas are locked before leaving. The invoices are brought to the manager’s office.

___12. The kitchen director computes the yields.

___13. The cooks enter and count all the items for the Starting Total.

___14. The manager verifies that the Starting Total on the Preparation Form is the same as on the Cook’s Form.

___15. The manager issues the tickets to the wait staff. The manager issues the cashier drawer to the cashier and verifies the starting amount.

___16. The manager checks the perpetual inventory.

___17. The wait staff gives the order tickets to the expediter.

___18. The expediter reads off the items to the cooks who start the cooking of the menu items.

___19. When completed, the waiter/waitress takes the dinner to the customer.

___20.The bill is totaled and given to the customer.

___21. The cashier verifies the amount and collects the money or charge.

___22. The cooks count the Balance Ending. In example: Starting Total is 34, and the ending balance is 21, leaving 13 as sold.

___23. The expediter itemizes the carbon copies: 13 shrimp dinners sold.

___24. The manager cashes out with the cashier. Ticket itemization: 13 sold.

___25. All three figures verified: cooks to expediter to cashier.

___26. The following morning the manager verifies the ending balance of the Cook’s Form to the Beginning Amount of the Preparation Form.

___27. The bookkeeper rechecks and verifies all the transactions of the previous night.