![]()

Chapter 36: Successful Budgeting and Profit Planning

All restaurants are in business to make a profit. To plan financially you must first set up a long-range plan detailing how much money you want the restaurant to return and when. This financial plan is the restaurant’s budget. This chapter will detail the steps for setting up a budget. The following chapter will describe the procedures for projecting actual operating costs, as well as how to recognize, analyze, and resolve cost problems.

Aside from being the restaurant’s financial plan, the budget is also used to control costs and account for sales and products. Budgeting is an accounting record and a tool used to evaluate how effectively the restaurant, management, and employees operated during the month. Based on this information, management can then recognize cost problem areas and act accordingly to correct them. Although many businesses maintain a yearly or quarterly budget, restaurants, because of their fluctuating operating performances, should use a monthly budget. The annual budget and profit and loss statement can then be easily computed by totaling all 12 monthly budgets. Monthly budgeting is the system described in this book. Once set up and operating, about four hours each month is all that will be required to compute the old budget and project a new one. Although the restaurant may be only in the pre-opening stage, it is imperative that you start to develop an operating budget now. As soon as the budget is prepared, you will possess the control for guiding the business towards your financial goal.

Initially the proposed budget may be under- or over-inflated. You may have overruns, but at least you will be starting to gain control over the organization, rather than the organization controlling you. After a few months you will have past operating budgets to guide you in projecting new ones. The budgeting process will become easier and more accurate as time goes by.

There are many other benefits to preparing and adhering to a monthly operational budget. Supervisors and key employees will develop increased awareness and concern about the restaurant and controlling its costs. This involvement will invariably rub off on the other employees. A well-structured, defined budget and orderly financial records will aid you in obtaining loans and will develop an important store of information should you decide to expand or sell in the future. Cost problems can be easily pinpointed once the expense categories are broken down. Last, you will become a better manager. Your financial decisions and forecasts will become increasingly consistent and accurate, as more information will be available to you. Financial problems may be seen approaching down the road rather than suddenly cropping up and forcing you to act quickly when you are uninformed. Management all too often reacts to a problem’s symptoms, instead of curing the disease. Budgeting will give you the tool for an accurate diagnosis

PROJECTING THE OPERATIONAL BUDGET

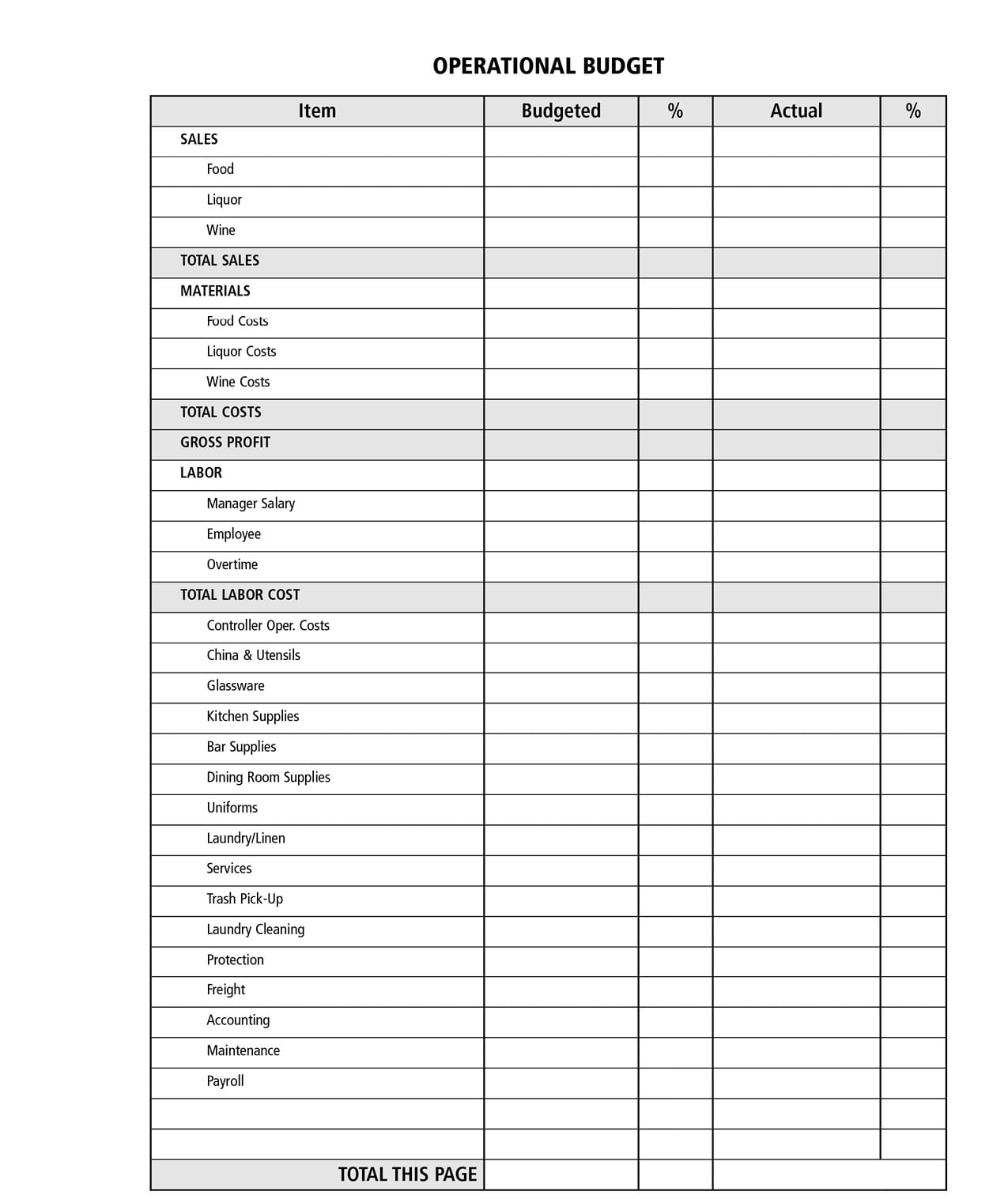

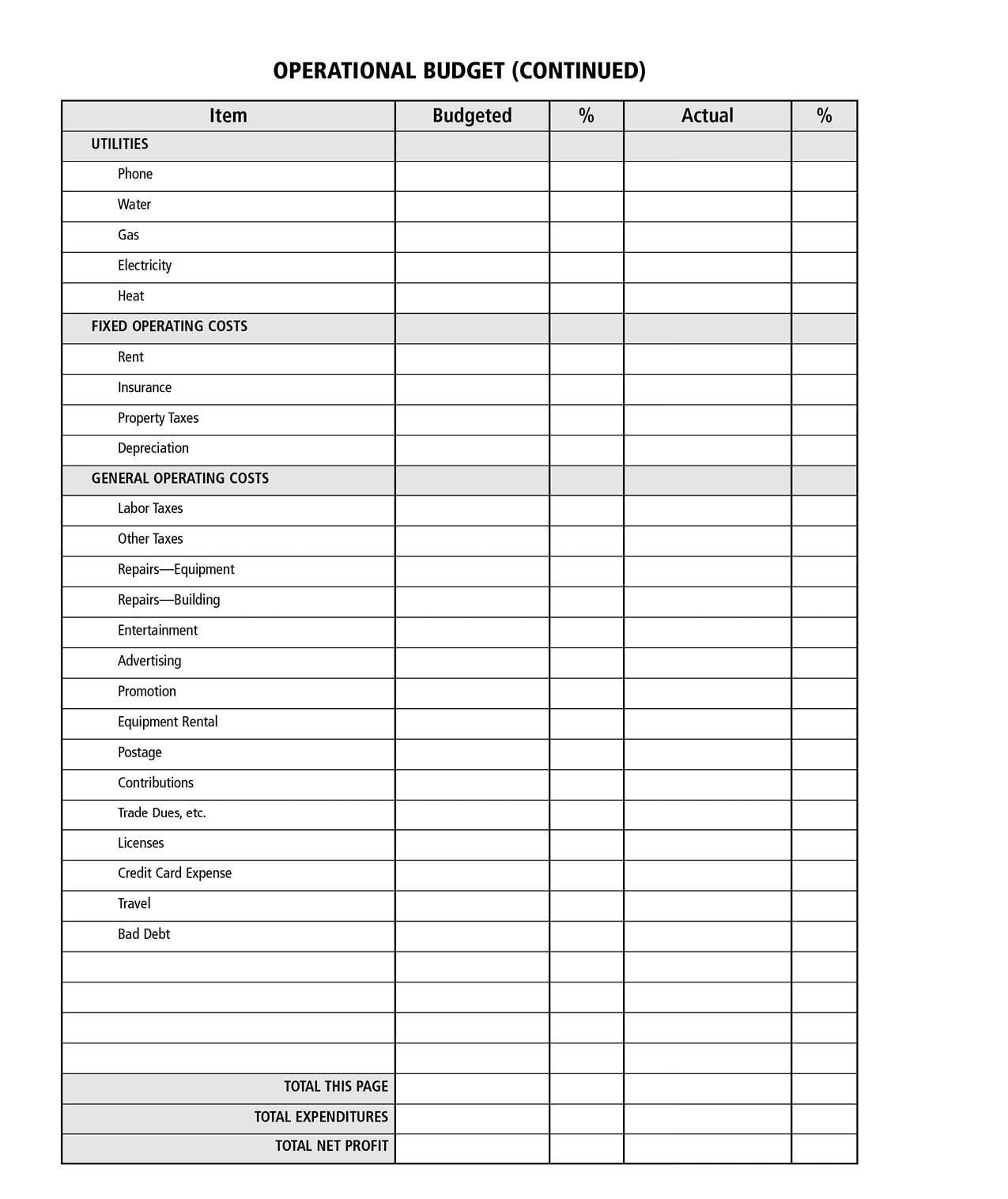

This section describes in detail all of the operational costs listed on the Operational Budget (which can be found at the end of this chapter), as well as how to accurately project each expenditure and revenue for the following month.

TOTAL SALES

Projecting total sales is the most crucial and difficult aspect of budgeting. The fact that it is impossible to know how business will be from day to day makes budgeting total sales a perplexing task. Most costs are either variable or semi-variable, which means they will fluctuate directly in relation to the total monthly sales. Thus, accurately projecting these costs depends largely upon using an accurate total sales figure. Projecting total sales, at first, will be difficult — and most likely inaccurate — but after several months of operation, your projections will be right on target. You will be surprised at how consistent sales and customer counts are and how easy it will be to consistently budget accurately.

The initial budgets may be unrealistic expectations. Sales will probably be low, as you will not have been able to build a substantial clientele or reputation. Operating costs will be higher than normal. It will take a couple of months to streamline and build an efficient restaurant even with the best-laid plans. Labor and material costs will be extremely high, as there will be a lot of training, low productivity, and housed food, liquor, and wine. All of these costs are normal and should be anticipated. Profit margins will be small and possibly nonexistent.

This period of time (four to 12 weeks) should be used to ensure that your product is perfected and all the bugs are worked out of the systems. This period is no time to cut back on costs. Your intention is to be in business for a long time. Allocate sufficient funds now to make sure the business gets off on the right foot and profits will be guaranteed for many years. Schedule a full staff every night to make certain all details will be covered. Discontinue those items that are passable but not of the quality level desired. Slow, clumsy service and average food will never build sales. Strive for A-1 quality products and service. Constantly reiterate to employees this primary concern and before long they will self-monitor the quality. Once you develop a clientele and a solid reputation for serving consistent, quality products, the budget and profits will fall into place. There are eight basic steps for projecting total sales:

1. If possible, use last year’s customer count. This information can be found in last year’s Daily Sales Report Form. Projections for the first year can be based upon prior months’ reports and educated estimates.

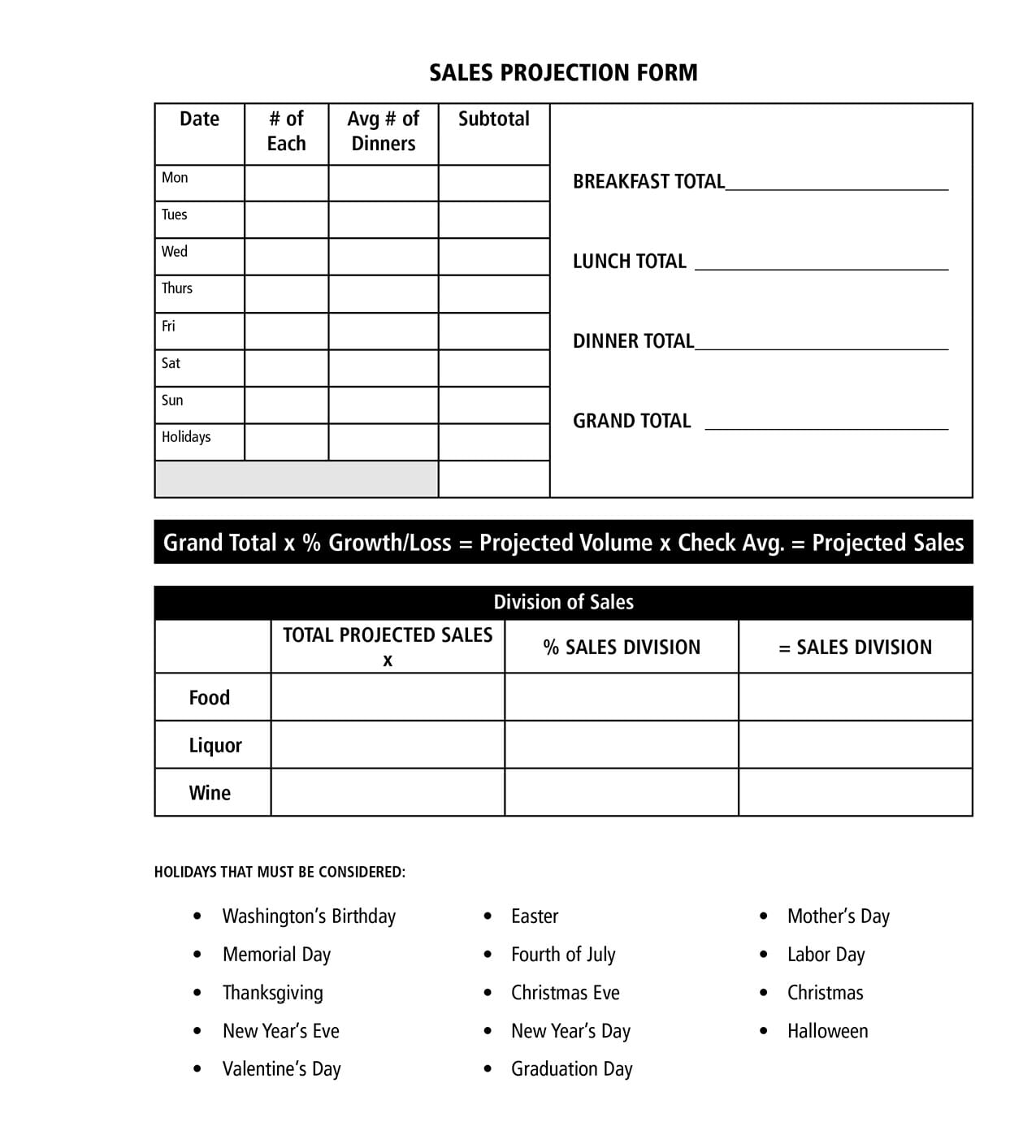

2. Using the Sales Projection Form (which can be found at the end of this chapter) and a calendar, calculate the number of days in the month. Enter this figure in the first column. From the information in #1, calculate the average number of covers served each day. Enter this figure in the second column. Compute the average number of covers served on any holidays that may be in the month; include scheduled functions, banquets, and large parties in this total.

3. Multiply the number of days in the month by the average number of covers served for that day; enter the result in the “Subtotal” column. Add the eight “Subtotal” columns to arrive at the grand total.

4. Review and analyze the growth in customer counts during the past year, current year, and current month. Based upon past customer counts determine the percentage of growth or decline in growth anticipated in the coming month. Percentage of growth or decline can be computed by subtracting the most recent period of customer counts by the past period of customer counts. The difference is then divided by the actual number of dinners served during the past period of time. A negative percentage figure shows a drop in customer counts. A positive figure indicates the percentage of increase.

When computing and analyzing these computations, keep in mind that each period of time must have the same number and type of days. In other words, you can only accurately compare months that have the same number of Mondays, Tuesdays, and so forth, since sales are different for each day; otherwise the results and analysis would be inaccurate. The most accurate way to analyze the percentage of growth or loss is to compare the previous month to the same month last year and then compare the percentage to the current month. Remember to only examine actual cover counts as indicators of growth; changes in sales may be the result of a price change.

5. Multiply the percentage of gross or loss by the grand total. Add the result to the grand total to compute the projected volume, or number of dinners. Subtract this figure instead if you are multiplying by a negative percentage figure that indicates a loss in customer counts.

6. Multiply the projected volume by the average check of the past month. The average check amount may be located on the Daily Sales Report Form. Adjust this figure if a price increase will be occurring during the month. Breakfast, lunch, and dinner sales may all be projected together unless the percentage of growth or loss is suspected in one area and not in the other two. A separate chart for each category should then be used to project each sales amount; simply add all three figures together to compute grand total of sales.

7. Compute individual food, liquor, and wine sales by simply dividing total sales by the average percentage of sales on last month’s Daily Sales Report Form. A restaurant budgeted at $25,000 in sales that has a division of sales at 70 percent food, 20 percent liquor, and 10 percent wine would have a breakdown of $17,500 food, $5,000 liquor and $2,500 wine sales.

8. The final step in budgeting sales is to enter the budgeted amount for each day on the Daily Sales Report Form. To compute the budgeted amount for each day, divide the total projected sales by the number of days in the month. This amount is the budgeted sales for one day. Enter this figure on line one of the first day of the month. Add this same amount to itself to compute the budgeted sales for day two and continue adding this same amount to itself until you have computed the sales for each day. Double-check your calculations by running a tape on the sales. The total must equal the total budgeted sales projections. Breaking down sales this way will enable the manager to see exactly where actual sales are in relation to budgeted sales. On a daily basis, enter the amount over or under budget in sales in the appropriate column (Use parentheses and/or a red pencil to enter sales that are under budget.).

MATERIAL COSTS

Material costs will fluctuate directly with the sales variance. More food, liquor, or wine sales will result in higher material costs. In budgeting material costs, the important figure to analyze is not the actual cost but the percentage of cost, or the cost-of-sales percentage, as it is more commonly known. Compute the cost-of-sales percentage by dividing the actual cost of the category by the category’s total sales. The result will be a percentage figure. This formula will present an accurate indication of the category’s costs, as the cost of sales are proportionate to each other.

The cost-of-sales percentages for each category — food, liquor, and wine — were projected in the previous chapters when determining the selling price of each item. Food cost was projected at between 35 and 40 percent, liquor, 18 to 25 percent, and wine, approximately 40 percent cost of sales. Enter the percentage figure used in the previous sections in the “Budgeting Percentage” column. This percentage figure can be used initially in order to project the first month’s budget. After several months of operation, the actual figure can be substituted.

Multiply the individual material costs by each respective budgeted percentage; the results are the budgeted cost amounts. If food sales were budgeted at $100,000, and the food cost percentage was estimated at 40 percent, the budgeted food cost would be $40,000. Increases in product costs will raise the actual cost-of-sales amount; adjust the budgeted amount accordingly. However, be certain that if an increase is anticipated, the increase will affect the following month, which is what is being budgeted. Items purchased at a higher price and then stored in inventory will have no effect upon the following month’s actual cost of sales, as the product will not have been used. Add all three budgeted costs to compute the total budgeted material costs. Subtract the total gross costs from the total sales to compute the gross profit dollar amount. Divide gross profit by total sales to calculate the gross profit percentage.

LABOR

Manager Salary

Manager salaries should be a fixed monthly cost. Total all the manager salaries for one year; divide this figure by the number of days in the year, and multiply this cost by the number of days in one month. Salary changes during the year will require adjustments. When owners take an active part in the management of the restaurant, or when the company is incorporated, the owners should have their salary amount included in this category.

Employee Salary

The employee salary expense is a semi-variable cost that will fluctuate directly with total sales. Employee labor costs have a breakeven point, the point where the labor cost is covered by the profit from sales. As this point is reached and total sales increase, the labor cost percentage will decrease, increasing net profit. Thus, the cost of labor is determined by its efficiency and by the volume of sales it produces. Multiply the projected total sales by the average labor cost percentage to arrive at the anticipated labor cost dollar amount. Adjust this figure in relation to the amount of employee training anticipated for the month.

Overtime

Overtime should be nonexistent — or at least kept to an absolute minimum. No amount should be budgeted for overtime. Money spent on overtime usually indicates poor management and inefficiency. Bookkeepers should be on the lookout for employees approaching 40 hours of work near the end of the week. Carefully prepared schedules will eliminate 98 percent of all overtime work and pay. Employees who wish to switch their schedules around should only be allowed to do so after approval from the manager.

CONTROLLABLE OPERATIONAL COSTS

|

CONTROLLABLE OPERATIONAL COSTS: Supplies |

|

|

China and Utensils |

Glassware |

|

Cost of china and utensils bought should be a consistent amount and percentage of sales for each month. Review Chapter 10, “Successful Management of Operational Costs and Supplies.” |

Same as china and utensils. |

|

Bar Supplies |

Dining Room Supplies |

|

Same as china and utensils. |

Same as china and utensils. |

|

Uniforms |

Laundry and Linen |

|

The uniform expense will depend upon the state in which the restaurant is located and individual management policies. Some states allow the company to charge the employees for uniforms; others do not. Many restaurants that do charge employees for uniforms do so at cost, which, if done correctly, should cost the restaurant nothing but administrative time. |

Laundry and linen buying should be a consistent monthly expenditure, as laundry and linen is usually purchased once or twice a year, in bulk. This expenditure column is for the purchase price only; cleaning is computed in a separate column, under “Services”. |

|

Office Supplies |

Kitchen Supplies |

|

Cost of office supplies should be a fixed dollar amount each month. Capital expenditures must be depreciated. |

Same as china and utensils. Capital expenditures for equipment with utility for more than one year generally must be depreciated over the item’s anticipated life span. |

|

CONTROLLABLE OPERATIONAL COSTS: SERVICES |

|

|

Laundry Cleaning |

Protection |

|

Cleaning of laundry is a variable expense directly related to total sales. Multiply last month’s percentage of cost by budgeted sales. Adjust the figure for price increases. |

Protection should be a consistent, fixed monthly expenditure. Service-call charges should be coded to “Equipment Repairs” under “General Operating Costs”. |

|

Legal |

Accounting |

|

Legal services are a variable expense that can fluctuate greatly. Estimates for most legal work can be obtained, but it is best to budget a little each month to cover periodically large legal fees. |

A semi-fixed expense depending upon the amount and the type of accounting services used. Once set up and operating, the accounting expense should be a consistent monthly charge except for an annual tax-preparation and year-end audit fee. |

|

Freight |

|

|

This expense may not be applicable to all restaurants. Freight is the expense incurred shipping material via rail, truck, or other method to the restaurant for exclusive use in the restaurant. Freight charges are usually incurred only by businesses in remote areas or when the restaurant purchases a product and then has an independent company deliver it. |

|

|

Maintenance |

Payroll |

|

Maintenance should be a fixed monthly expenditure if you are using a maintenance service company with contract service. |

A semi-fixed expense fluctuating directly with the number of employees on the payroll. Restaurants not utilizing a computerized payroll service will not have a payroll preparation expense. The wages paid to the bookkeeper are included in the employee labor expenditure. |

|

CONTROLLABLE OPERATIONAL COSTS: UTILITIES |

|

|

Water |

Heat |

|

Water should be a semi-variable expense. |

Heat includes the cost of any heating material used but not listed above, such as coal, wood, and oil. |

|

Telephone |

|

|

Telephone service should be a relatively consistent monthly expense. All long-distance phone calls should be recorded in a notebook (Your local office-supply store has a specially designed book for this purpose.). The itemized phone bill should be compared against the recorded phone calls to justify each one. |

|

|

Gas |

Electricity |

|

Gas may be a variable or semi-variable expense depending upon the type of equipment it operates. Gas used in heating will be a variable expense, because more will be used during the winter months than in the summer. |

Electricity may be a variable or semi-variable expense depending upon the type of equipment it operates. Electricity bills are normally higher during the summer months, as this is when the air-conditioning units are used. |

FIXED OPERATING COSTS

|

FIXED OPERATING COSTS |

|

|

RENT |

INSURANCE |

|

The monthly amount of rent or, if the building is leased, the monthly lease. Certain business-rental and lease agreements also include payment of a percentage of the total sales or per-tax profit amount. Should this be the situation, use the budgeted total sales figure and project the anticipated amount due. Enter this amount and the total rent amount in the “Budgeted” column. |

Total all insurance premium amounts (fire, theft, liability, workers’ compensation, etc.) and divide by 12. This figure will equal the average monthly insurance expense. |

|

PROPERTY TAXES |

DEPRECIATION |

|

If applicable, divide the annual property tax amount by 12. This figure will equal the average monthly property tax amount. |

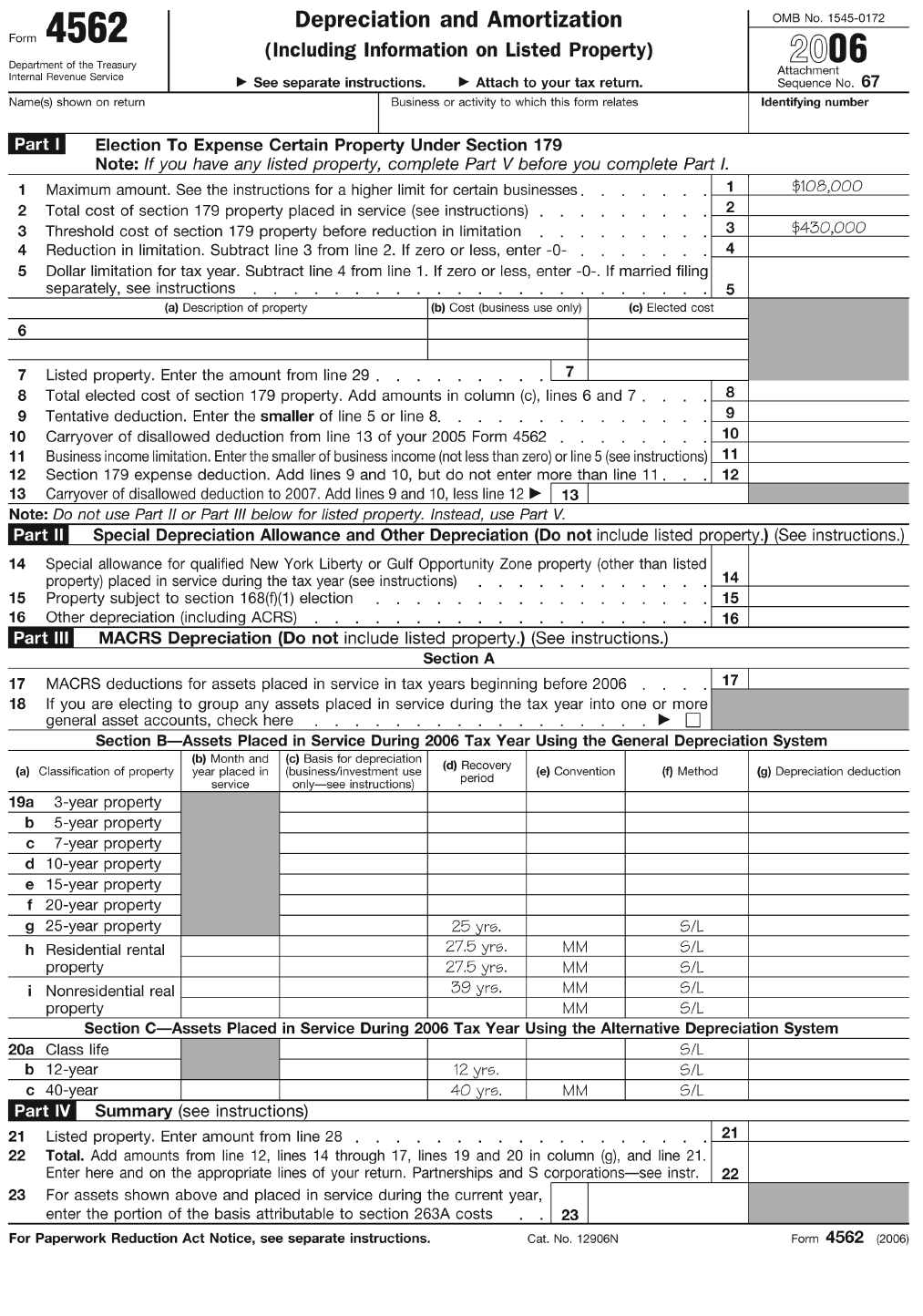

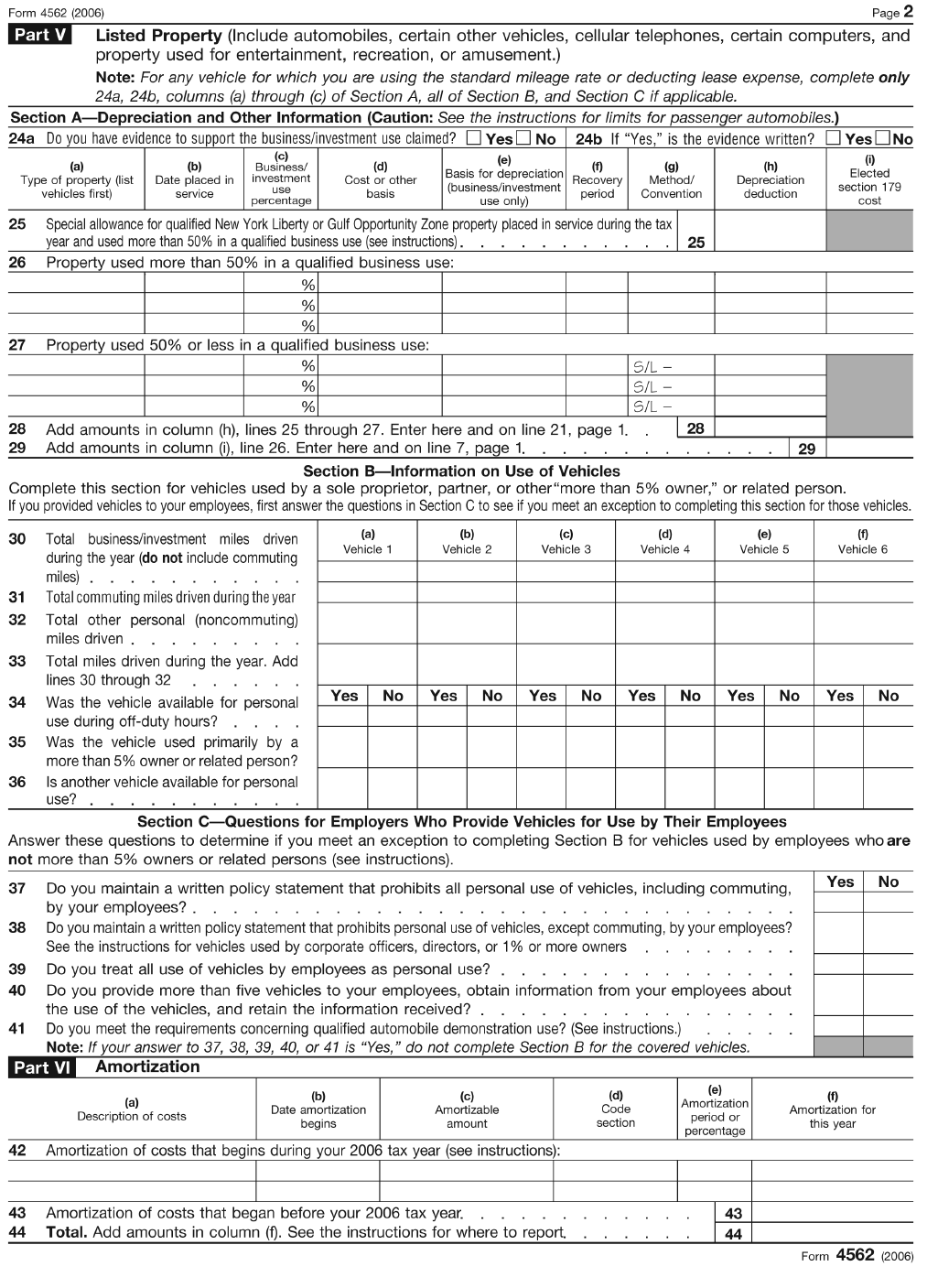

Depreciation will be discussed in detail below |

Depreciation

Depreciation may be defined as the expense derived from the expiration of a capital asset’s quantity of usefulness over the life of the property. Capital assets are those assets that have utility of more than one year. Because a capital asset will provide utility over several years, the deductible cost of the asset must be spread out over its useful life — over a specified recovery period. Each year a portion of the asset’s cost may be deducted as an expense.

Some examples of depreciable items commonly found in a restaurant include: office equipment, kitchen and dining room equipment, the building (if owned), machinery, display cases, and any intangible property which has a useful life of more than one year. Thus, items such as light bulbs, china, stationery, and merchandise inventories may not be depreciated. The cost of franchise rights is usually a depreciable expense.

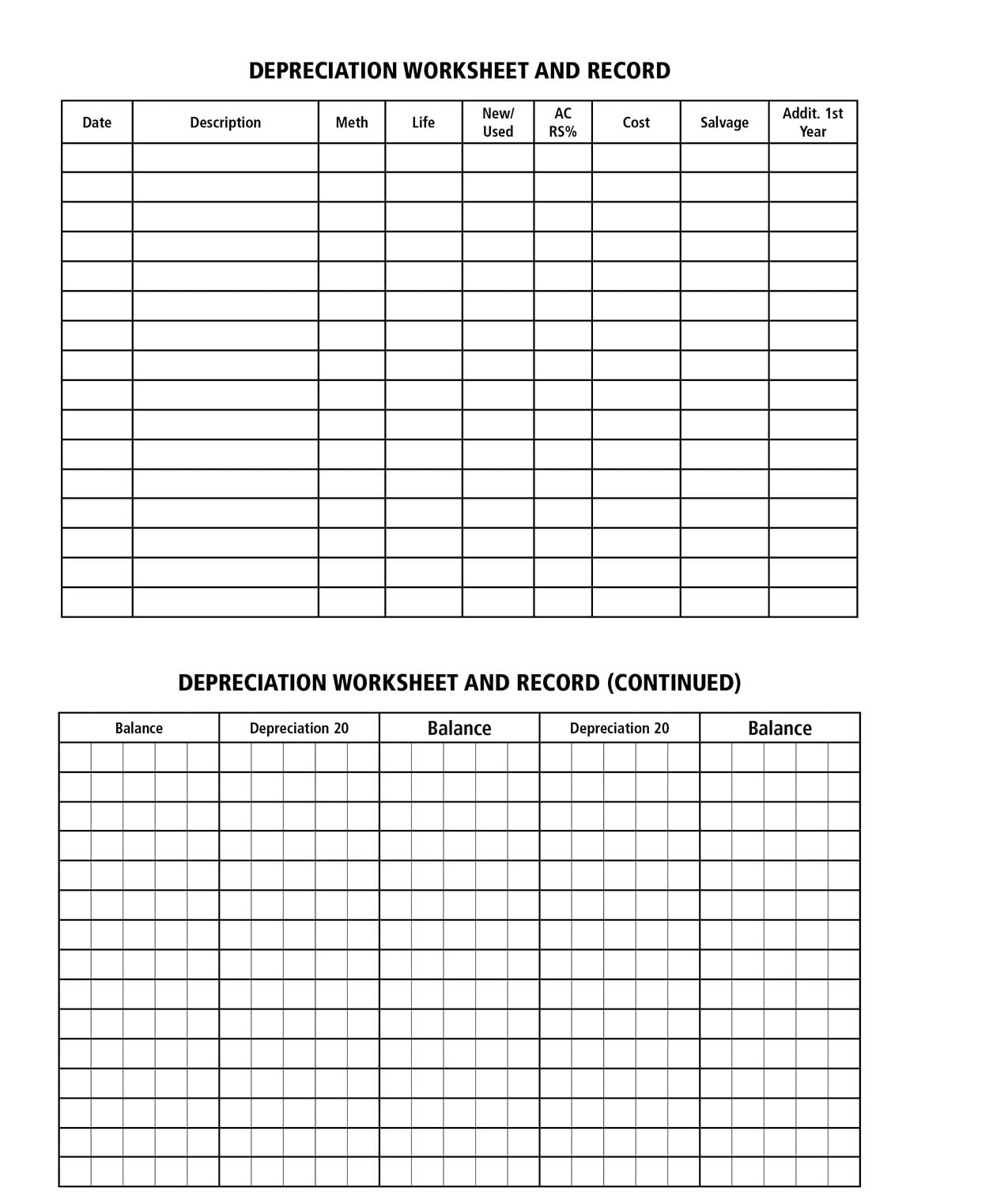

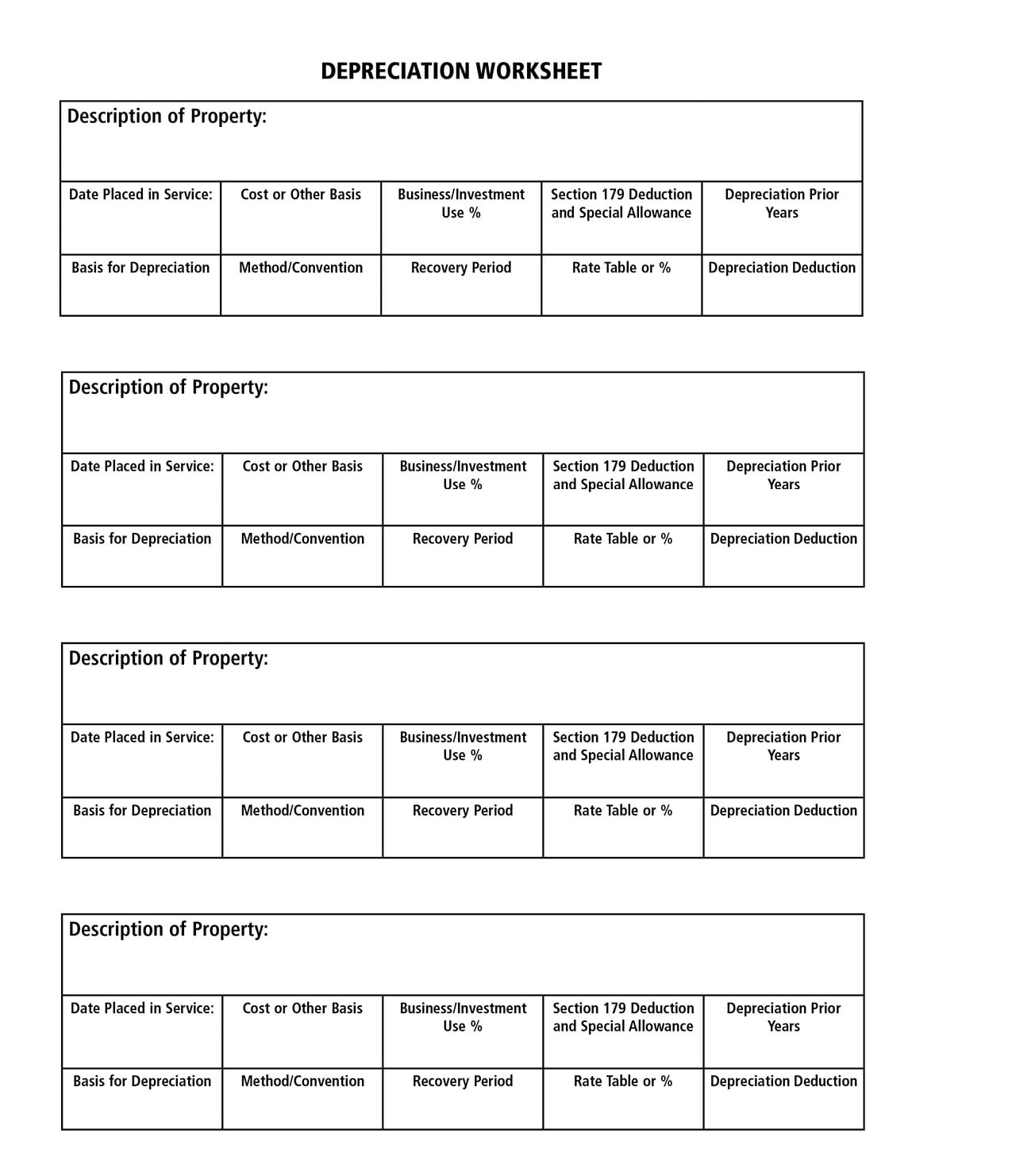

The Depreciation Worksheet and Record at the end of the chapter will be a great aid in computing depreciation amounts, regardless of the methods used. Record the purchase of all depreciable items right away and you will keep on top of this complex and time-consuming area. The IRS publishes guidelines for the number of years to be used for computing an asset’s useful life.

GENERAL OPERATING COSTS

|

GENERAL OPERATING COSTS: TAXES |

|

|

Payroll and Labor Taxes |

Other Taxes |

|

The tax amount the employer is required to contribute to the state and federal government. A separate tax account should be set up with your bank to keep all the tax money separate. Labor taxes include: Social Security, Medicare tax, federal unemployment tax, and state unemployment tax. |

Includes all miscellaneous taxes, such as local taxes, sales tax paid on purchases. This column is for any tax the restaurant pays for goods and services. It is not for sales tax or other taxes the restaurant collects, as they are not expenditures. Federal income tax is not a deductible expenditure and should not be listed here, either. |

|

GENERAL OPERATING COSTS |

|

|

REPAIRS AND MAINTENANCE: EQUIPMENT |

REPAIRS AND MAINTENANCE: BUILDING |

|

Includes the cost of scheduled and emergency repairs and maintenance to all equipment. Always budget a base amount for normal service. Adjust this figure if major repairs or overhauls are anticipated. |

Includes the cost of minor scheduled repairs and emergency repairs and maintenance to the building. Always budget a base amount for repairs/maintenance. Large remodeling or rebuilding projects should be budgeted as a separate expenditure and depreciated. |

|

ENTERTAINMENT |

ADVERTISING |

|

Entertainment includes bands, music, entertainers, and so forth. |

Advertising includes all the costs of advertising the restaurant, including television, radio, mailing circulars, newspapers, etc. |

|

PROMOTIONAL EXPENSE |

EQUIPMENT RENTAL |

|

The expense of promotional items: key chains, calendars, pens, free dinners, T-shirts, sponsorship of events, etc. |

This cost is the expense of either short- or long-term renting of pieces of equipment or machinery. |

|

Postage |

Contributions |

|

Postage paid for business purposes. |

These are all contributions paid to recognized charitable organizations. |

|

Trade Dues, Etc. |

Licenses |

|

Includes dues paid to professional organizations such as the National Restaurant Association. Trade magazine subscriptions should also be entered in this category. This expense should be divided by 12 to apportion the cost from the month in which it occurs. |

The expense of all business and government licenses: operating licenses, a health permit, liquor licenses, etc. This expense should also be divided by 12 to apportion the cost from the month in which it occurs. |

|

Credit Card Expense |

Travel |

|

Credit card expense can be computed by multiplying the service-charge cost-of-sales percentage by the total projected credit-card sales volume. |

Travel includes the expense of ordinary and necessary travel for business purposes for yourself and your employees. |

|

Bad Debt |

|

|

This expense should be nonexistent if the proper procedures for handling credit cards and checks are enforced. Normally, the full amount of a bad debt is a tax-deductible expense. However, you must prove the debt is worthless and uncollectible. In some states, the employee who handled the transaction may be held legally liable for the unpaid amount. |

|

Total Expenditures

Add the total budgeted expenditures from both pages and enter the figure in this column.

Total Net Profit

Subtract Total Budgeted Expenditures from Total Sales. The result is the total net profit (or loss). Divide the Total Net Projected Profit by projected Total Sales to compute the projected Pre-Tax Net Profit Percentage. Total projected sales minus total material costs will equal the gross profit amount.