CHAPTER 1

WHAT IS FAMILY CAPITAL, AND WHY DO WE NEED IT?

W hether it’s solving a Rubik’s Cube or the daily crossword puzzle, people like to tackle problems and come up with the right answer. I’ve been perplexed by a puzzle containing four numbers: 12, 11, 7, and 5. These numbers reflect the average self-employment rates of four different racial groups in the United States in recent years.1 Asian Americans (12 percent) have had the highest self-employment rate while African Americans (5 percent) have had the lowest, with whites (11 percent) and Hispanics (7 percent) falling in between.2

The riddle is: what causes the differences between these four groups? My curiosity was further piqued when I discovered another pair of enigmatic numbers: 24 and 5. The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM), a worldwide survey of global entrepreneurial activity, noted that 24 percent of the Chinese population are engaged in early start-up activity, but only 5 percent of Russians are similarly engaged.3 Are the Chinese really five times more entrepreneurial than the Russians, and if so, why?

Additionally, I have been concerned that business start-up rates have been declining in the United States over the past several decades—despite entrepreneurship being touted in the media as the wave of the future and universities putting a much greater emphasis on entrepreneurship in recent years. Start-ups in the US have declined about 20 percent over the past decade; a little over 500,000 start-ups per year existed ten years ago, but only 414,000 in 2015.4

Moreover, millennials (those between the ages of twenty and thirty-four) are much less likely to start new businesses than those from previous generations.5

As someone who has studied, taught, and researched entrepre-neurship and family business for over three decades, I’m supposed to be able to understand and explain why some individuals start businesses that succeed, why others start businesses that fail, and why others don’t start businesses at all. When I discuss the possible causes of the differences in self-employment rates between the various racial and ethnic groups with business leaders, colleagues, and students, opinions vary widely. I have been told that Asian Americans, particularly the Chinese, just work harder and have a culture that encourages entrepreneurship; that the long history of discrimination against African Americans has set them back compared to other racial groups; and that Hispanics have an inherent culture of entrepreneurship but have had difficulty gaining financing through banks. Some also say millennials are too soft and thus not well-suited for an entrepreneurial career.

All these explanations are plausible answers to the puzzle. However, they seem rather simplistic and incomplete. In my thirty-plus years of experience working with entrepreneurs and family businesses, I have found what I consider a better answer to this puzzle: family capital. Family capital is the human, social, and financial resources available to individuals or groups as a result of family affiliation. When families have these resources available, the process of starting a business becomes easier. Without it, self-employment is difficult, if not impossible. Family capital is more than just a key ingredient in start-up success; it’s society’s basic building block for wealth-creation and economic prosperity.

In this chapter, after defining some basic terms, I will examine how family capital is created and its advantages. I will then present a case study of one of my clients—Mary Crafts, founder of Culinary Crafts— to describe how she developed family capital within her own family and used it to start and grow her business. I will also describe a study my research team conducted using a large data set to highlight how youths in the United States who have access to family capital are more likely to start successful businesses as compared to youths with less access. This study will focus our attention on the economic implications for societies that lack family capital. At the end of the chapter is a “Family Capital Inventory” so that you can rate your own family along the various dimensions of family capital.

Some families have a structure that’s typically labeled the “nuclear” or “traditional” family: a married father and mother with children. However, this familial pattern has declined in recent years.6 Today, we see more blended families as a result of divorce and remarriage, families led by cohabiting partners, families led by a single parent (generally a woman), and families headed by same-sex couples. Moreover, in certain parts of the world, particularly those with a large Muslim population and in tribal Africa, polygamy is a significant family structure. Therefore, I will use the following catch-all definition: a family is comprised of individuals who identify themselves as a family unit, are recognized by others as a family, and share a common biological, genealogical, and/or social history. A possible fourth factor is governmental recognition of these individuals as a family unit, particularly important given that governmental sanction of certain family structures generally provides legal protection for family members. For example, in the case of divorce, the state can require alimony for an ex-partner. However, certain family structures (e.g., same-sex and polygamous) may meet the other three criteria while not being recognized by the state as a family.

Fledgling entrepreneurs often have many good ideas but few of the resources needed to turn them into reality. Where can they get the resources to get started? Although entrepreneurs armed with a well-developed business plan can attract money, support, social connections, and other resources from venture capitalists or banks, this is the exception. In most cases, fledgling entrepreneurs are forced to rely on their own resources or on family resources to launch a business.

Primarily three types of family capital (or resources) have been associated with successful start-up activity and self-employment:7

» Skills, knowledge, and labor of family members, or “family human capital”

» Social connections and reputation shared by family members, or “family social capital”

» A family’s financial and tangible assets, or what I will call “family financial capital”

These three are valuable to family members even if they have no desire to start a business, since family capital can help them in other ways to achieve their individual goals. I will briefly discuss each of the types in turn.

Families create human capital by sharing knowledge with family members that can help them in their everyday lives and, in some cases, help them start and run a business.8 Research has shown that children of self-employed parents are three times more likely to become self-employed than children whose parents are not.9 Through conversations around the dinner table, summer employment in the family business, or simple observation of their parents, children learn how to create new products, service customers, and make sales. Certain industries such as farming, construction, funeral services, and liquor sales are known for having tried-and-true business tactics that are passed down from generation to generation as family knowledge. The oldest known family business, the Kongo Gumi construction company in Japan, was founded in AD 578 and is being managed by fortieth generation family members.10 By effectively mentoring younger family members, family elders pass on the secrets of business: how to grow crops, build homes, make tequila, or prepare bodies for burial. One study reported that “business outcomes are 15 to 27 percent better if the owner worked in a family business prior to starting his or her own business.”11 Living in a family business environment would have “a large, positive, and statistically significant effect for all business outcomes.”12

I’ve seen these positive effects in my own family. My father, Bill Dyer, worked with his father at the Dyer Grocery store in Portland, Oregon. While delivering groceries, Bill learned a lot about running a small business. He also learned that a career as a grocer was not in his future—the hours were too long and the pay too little. He decided to go to college, earn a PhD, and eventually become a college professor—a career path seen as being viable since his half brother, Jack Gibb, received his PhD in psychology from Stanford University. Bill’s academic career began in sociology but changed in the 1960s when Jack introduced him to the new field of organizational behavior. My father began to apply his training in sociology to the field of business and eventually finished his career as dean of the business school at Brigham Young University. As I watched my father over the course of his career, I was attracted to the lifestyle and career opportunities an academic career provided. I was fortunate to do consulting with my father and even took a class from him on change management while I was an MBA student. Moreover, we had countless discussions over the dinner table or while fishing or playing golf about his career, life as a professor, and theoretical and practical issues in business—all of which helped to prepare me for an academic career in the field of management. With this background, both my brother Jeff and I decided to follow our father’s footsteps into academia. My son Justin has followed the Dyer family path by becoming an academic as well. What’s even more interesting is how closely our research connects us to each other: my father’s early work in sociology was on roles and conflict within families, my research and consulting has focused on family businesses, and my son Justin received his PhD in family studies from the University of Illinois. (His dissertation was on how families try to maintain a relationship with an incarcerated father. I have always thought there could be something Freudian about his dissertation topic—maybe Justin had dreams of locking me up in prison after I disciplined him.) The theme of “family” seems to follow the Dyers: I have first-hand experience with family modeling and knowledge sharing.

Family norms of reciprocity (i.e., if I help you, you’ll help me) may prompt family members to provide labor needed to carry out a project or help start a business. I’ve often consulted with siblings, spouses, and other family members who have built a successful business together. A number of years ago, I consulted with General Growth Properties, a billion-dollar real estate construction and investment firm started by Martin and Matthew Bucksbaum. As I worked with Martin and Matthew regarding the issues of succession in their company, I saw that Martin had the skills needed to identify potential locations for new shopping malls. Matthew, on the other hand, was more adept at running the day-to-day affairs of the business. They made an excellent team, a collaboration that would not have been possible without their brotherly connection. By utilizing their family human capital, they eventually built one of the largest real estate development firms in the United States.

Family members have unique advantages in developing social capital between family members and their family’s stakeholders (e.g., friends, clients, business associates, community leaders) given that they typically cultivate and nurture positive relationships.13 Family social capital refers to the bonds between family members and those outside the family—relationships that can be used to obtain the resources needed. Family social capital can be even more effective than typical social connections. When outsiders deal with a member of a family that possesses family social capital, they understand that behind that family member stands an entire network of support. Therefore, commitments made by someone representing a family aren’t empty promises; obligations are generally shared within the immediate family and may extend to more distant family members as well.

I have found that a unique status is often ascribed to business-owning families, which facilitates important relationships for a family member who wants to start a business. A family’s status in the community brings with it certain benefits not available to those outside the family.14 An example of the impact of family social capital on start-up success can be found in the early story of Microsoft. Founder Bill Gates was able to sell his DOS operating system to IBM because his mother sat on the board of a foundation with the chairman of IBM, John R. Opel, and helped Bill make that connection. So Bill Gates was able to convince IBM to bundle Microsoft’s software with its personal computers. Without the help of Bill Gates’s mother, Microsoft might not have been able to gain such a dominant position in the software industry.

Family connections also bring advantages to family members by creating a positive reputation for the family in the community, which, in turn, leads to goodwill and trust.15 An SC Johnson advertisement featuring Fisk Johnson, a fifth-generation Johnson, builds on the family connection: “For years, we’ve said that SC Johnson is a family company. . . . To us, family is more than a relation. It’s our inspiration. Inspiration to care. To try to do what’s right. To always be better. Times may have changed since my great-great-grandfather started SC Johnson, but the inspiration behind what we do remains exactly the same.”16 Creating and protecting one’s family brand name can help family members gain access to resources they wouldn’t obtain otherwise.

Financial capital and other tangible assets for a family business may include office space in the family home, family vehicles, phones, and computers. For example, it’s well known that Steve Jobs benefited from his parents’ generosity when they allowed him to start Apple in their garage. Scholars David Sirmon and Michael Hitt have noted that a family’s “survivability capital”—the pooled financial capital of the family—can help a new business survive and grow. They write, “Survivability capital can help sustain the business during poor economic times. . . . This safety net is less likely to occur in nonfamily firms due to the lack of loyalty, strong ties, or long-term commitments on the part of employees.”17 Family members not only draw upon family financial resources during difficult times but also turn to family members to find start-up money. Such pooling of capital has been instrumental in the proliferation and growth of Chinese family businesses.18 One study reported that Asian Americans borrow three times more frequently from family and friends than do white Americans.19 Another study noted that only 7 percent of African Americans borrowed money from spouses, family, or friends to start a new business, but 23 percent of Asian Americans did so.20 Finally, in their extensive study of start-up rates among racial and ethnic groups in the United States, Robert Fairlie and Alicia Robb, in their book Race and Entrepreneurial Success, report that “an important limiting factor” for business start-ups was access to financial capital.21 Thus, a family’s ability to share financial resources with family members is a key factor in business start-up and success.

Family capital tends to be superior to financial, social, and human capital obtained from individuals or institutions outside the family. There are four primary advantages of family capital:

» It is difficult to imitate. In other words, others may not be able to replicate a family’s unique resources.

» It can be mobilized quickly.

» It has low transaction costs. Because of high trust within the family, family members probably don’t need to put up collateral or involve lawyers to create legal documents when borrowing money or other resources from family members.

» It can be transferred efficiently across generations.

The following hypothetical example illustrates how these advantages play out for members of a family. Roxanne, a recent college graduate with a degree in hospitality management, returns to her hometown intent on starting her very own restaurant. She has a dynamite idea: Roxanne’s Restaurant, a cafeteria-style restaurant specializing in Italian cuisine. However, thinking of a good idea is the easy part. To actually get it off the ground, she needs advice, labor, some connections, and some capital. Luckily, she has two ace-in-the-hole connections: her father owns the local hardware store, and she’s good friends with the daughter of the president of the largest bank in town. Which connection would more easily help her secure money and support?

Though Roxanne has a connection with the bank president, it won’t be so simple borrowing money from his bank. To get a formal meeting with him, Roxanne would likely need to call the president’s secretary to set up an appointment. Once in the president’s office, she would be greeted warmly; the bank president would assure her that he would do everything in his power to help her. However, there are limits to his control. An informal agreement is very unlikely in this case, as the transaction to obtain seed money would likely take time and require collateral or other security. Significant paperwork may need to be completed, and bank officials may require a formal, possibly lengthy, review before any funds could be released. Moreover, it is unlikely the bank president would be able to quickly and easily transfer his social capital to Roxanne, given that their relationship, though friendly, isn’t familial.

Contrast this with Roxanne’s connection to her father, the hardware store owner. Roxanne has learned how to start and run a business by watching her father, and likely trusts his judgment. She can set up a meeting with him quickly and obtain readily extended advice and financial help from her father to start her restaurant. If her father is strapped for cash, he can recommend Roxanne to other members of her family who may be willing to invest. Her father might also let her know of an out-of-work cousin with culinary skills who could help her start out at little or no cost. Her father might also introduce her to contacts who could help her launch the new business. Moreover, the family name and reputation might attract customers to the new restaurant.

Though not all families have the kind of relationships that encourage the sharing of human, social, and financial capital within the family—and clearly some nonfamily relations can act in a family-like manner—this example underscores familial advantages.22

Certain factors influence the accumulation of, and access to, family capital. Although some factors may seem obvious, it is nevertheless important to describe them explicitly.

Creating a family is the first requirement of family capital. Marriage (or some other type of union) is central to the formation of a family. Moreover, stable relationships are important to creating family capital, and marriage, although less stable than in years past, typically provides the best opportunity for family stability.

Family size is an important factor in creating family capital—the more family members available, the more opportunity to create and share resources. However, today’s birth rates are at historic lows when compared with birth rates of previous generations. In the past, children were generally seen as assets to help the family economically and to provide support for parents as they aged. But in today’s world children are often seen as liabilities: expensive to raise, a lot of work, and limiting the pursuit of other interests. And current birth control measures make it easier to avoid having children. However, despite the expense of raising children, a smaller family typically means less family capital—the larger one’s nuclear family and extended family are, the more likely a family member will have access to family capital.

Family members develop bonds of trust and reciprocity as they spend time together. As they work together, whether on household chores or on tasks for a family business, family members learn how to solve problems together, share information and resources, and develop a strong work ethic. Moreover, they develop a norm of reciprocity within the family, which is fundamental to the development of family capital. Additionally, time spent around the dinner table with children is crucial for sharing beliefs, teaching important values, and building stronger relationships.

One final aspect of family functioning that develops family capital is the family’s encouragement of formal or informal education that enhances skills and abilities. As the family’s combined reservoir of knowledge and skills increases, other members of the family can draw upon that to help them succeed.

I remember one founder of a large clothing manufacturer telling me how his children helped him run his business. He said, “When my sons were in college I told my first son that I needed an accountant in my business; I told my second son that I needed a salesman, and then told my third son that I needed someone with experience in manufacturing. They took my advice to heart and focused their college education in each of these areas. When they finished their degrees, they all had an important role waiting for them in my company. They are now all working for me and are doing well.” This father’s approach to the career counseling of his sons might appear heavy-handed, but its effectiveness can’t be denied. His business now has three trustworthy, hardworking executives with different skill sets that enhance the family’s pool of family capital.

Family skills and knowledge can be used in ways beyond just running a business. In my own family, I can turn to family members for legal and medical advice, tips on the housing market, advice about business and insurance, help in doing my taxes, or manual labor to help me move furniture from one room to another. (Now I just need a plumber in the family, but so far no such luck.) This advice and help is typically free and can be accessed quickly.

I first met Mary Crafts, founder of Culinary Crafts, in the fall of 2012. Mary was a business acquaintance of my daughter Alison, and Mary confided in Alison that she might need some consulting help with her family business. Her goal was to retire from active management of the business over the course of the next few years, leaving ownership to her two sons, Ryan and Kaleb, who had worked in the business for many years. She also wanted to explore how she might involve her daughter, Meagan, in the business even though Meagan had considerably less experience at Culinary Crafts than her two brothers. When I first met Mary, I was struck by her energy and charisma. I found out later that she had her own cooking show on TV, had catered events for celebrities like Oprah Winfrey, and was widely hailed as the Martha Stewart of the state (minus the felony conviction). Her company, Culinary Crafts, had won the Best of State caterer title for thirteen consecutive years and also won a Caterer of the Year award from the International Caterers Association. I ask all potential clients to tell their story about the start-up and the significant challenges and successes they have experienced. The following is a brief history of Culinary Crafts.

Culinary Crafts quite literally started out as a dream. One night Mary had a vision about a catering company. “I saw it all from beginning to end: how we’d help people through creating wonderful events, how I could build a successful company, and how we were going to be of real service to the community.” In 1984, armed with this vision and some money in family savings, Mary and her husband, Ron Crafts, started a small catering business working out of the kitchen in their home. They were conservative in spending as they began the business; their first mixer, a KitchenAid, was a gift from a generous neighbor who felt bad for Ron after learning he had to whip cream by hand. Mary recalls how things were difficult in those early days: “When times were tough, I wondered if we would make it as caterers. I would remember that dream where I saw all those catering vans lined up ready to go out, and I would stay committed to my dream.” In the beginning, Mary was trying to build a following and create sales but couldn’t afford childcare. As a young boy, Ryan would tag along and pull the Radio Flyer wagon full of breads, cookies, and other baked goods while Mary sold door-to-door. Soon he was tasked with tending the company’s herb and vegetable gardens. Ryan’s little brother Kaleb also started at an early age. One evening, Mary had no choice but to bring an eleven-year-old Kaleb to an event at the last minute and found the perfect job to keep him occupied: standing at the end of the buffet table and pointing guests in the direction of the dessert table. Mary gave him two simple instructions: say, “The dessert table is this way” and point in the correct direction. He performed beautifully—so much so that Mary didn’t go back right away to check on him. After all the guests had gone through the buffet line, she realized that Kaleb must be standing there with nothing to do. She quickly ran to the table, but Kaleb wasn’t there. She found him over at the dessert table, politely describing to the guests each dessert, recommending the ones that were his favorites, and proudly proclaiming that they were all made from scratch!

Over time, Ryan moved up the Culinary Crafts chain, working as dishwasher, one of the event setup crew, grill master, event manager, fleet manager, accounts payable and payroll clerk, and more. He currently works as president and chief operating officer and is responsible for company events and menus—Culinary Crafts clients come back because Ryan knows how to put on a great event. Kaleb gravitated to the sales side of the business and is currently the president of sales and marketing. He is particularly adept at corporate sales and secured a strong business relationship with the prestigious, popular Sundance Film Festival. Ryan and Kaleb purchased 49 percent of the company from Mary in 2013 and the remaining 51 percent in 2018.

Mary is proud to share the spotlight with her sons. She explains, “We’ve reached a point where Culinary Crafts is no longer just the ‘Mary Show,’ it’s the result of an entire catering team doing an incredible job day in and day out.” Mary continues, “Ryan and Kaleb grew up in the business. They know it inside and out and they are very good at what they do!” Daughter Meagan has been tasked with creating unique event decor, working on internal HR campaigns, and supervising on-site cooking. She is now stepping into business administration duties; as the marketing coordinator, she implements all marketing and social media campaigns. Her husband, Clayton Price, served for a number of years as an expert event manager. He now serves as the director of event operations, training all the service staff to maintain company quality standards. Jen Crafts, Ryan’s wife, is responsible for website updates and photo archives. Mary has cultivated a veritable army of skilled family members to help her both launch and grow the business.

One hiccup in the process of creating and growing Culinary Crafts was Mary’s divorce from Ron in 2010. Ron left the business in 2008 as a result of various personal and family issues. As business partners both Ron and Mary owned 50 percent of the business. As part of the divorce agreement, Mary decided that she would buy out Ron and become the sole owner, which happened in 2010. While this was quite painful for Mary both financially and emotionally, the company has continued to grow after Mary’s divorce from Ron. The business has started its fourth decade as a premier caterer and Mary and her family recently built and moved into a new 16,500-square-foot catering facility.

The story of Culinary Crafts helps us better understand how family capital is created and used to foster the successful launch of a business. Family savings and the use of the family kitchen were key resources that enabled the business to get started. Mary and Ron also had baking skills that led to the firm’s initial success, and later on, the business leaned heavily on the labor of Mary’s children. Rather than being forced to spend their limited capital on hiring and training employees, Mary and Ron were able to raise children that had the necessary skills to help Culinary Crafts grow. Furthermore, Mary’s reputation and social capital in the community was enhanced by her TV appearances and culinary acumen, which created a positive image for Mary, her family, and her business. The Craft’s path to success is not easy to copy, as competitors can’t easily mimic thirty years of parenting, teaching, and family togetherness.

A few studies have looked at relationships between family members and start-up activity, but little in-depth research has been done exploring the relationship between family capital and start-up success.23 To focus on this issue, my colleagues and I developed two hypotheses:

» Youths with access to family capital will start more businesses than those youths without access to family capital.

» The businesses of those youths who have a comparative advantage in family capital will survive longer and make more money than the businesses founded by youths with less family capital.

To test these hypotheses, we analyzed data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY97) conducted by the US Census. This unique data set gave us the ability to assess the family capital of over 8,000 randomly selected twelve- to sixteen-year-olds before they launched a business, observe if and when they started new enterprises, and measure the success of their businesses over time.24 During the fourteen-year duration of the study (1997 to 2010), 24 percent of the youths started a business while 76 percent did not.

To conduct our study, we created a baseline of the youths’ family capital when they were initially surveyed. We measured family human capital based on the parents’ education levels and whether or not the parents had been self-employed, reasoning that these measures reflected the skills and background that could be accessed by the youths. Family financial capital was measured by household annual net income and the total dollar amount of loans to the youth from the family, which measured the amount of money youths borrowed or might potentially borrow from family members. To measure family social capital, we used two questions. First, the youths were asked to rate their parents’ support of them, which essentially indicates how close the youths were to their parents and how much they could rely on them for help. The second asked youths to indicate the number of loans given them by family members, which shows whether the family is connected enough to repeatedly loan each other money. You’ll notice that this is a similar question to the one posed for family financial capital; we reasoned that the total amount of the loans would more likely measure the family’s financial resources while number of loans given to the youth would indicate the level of trust and social capital within the family. The variables in the NLSY97 aren’t perfect, but reasonably represent the three types of family capital. These variables largely focus on the parents’ impact on the youth—the parents’ education and business experience, their wealth, and their relationship with the youth.25

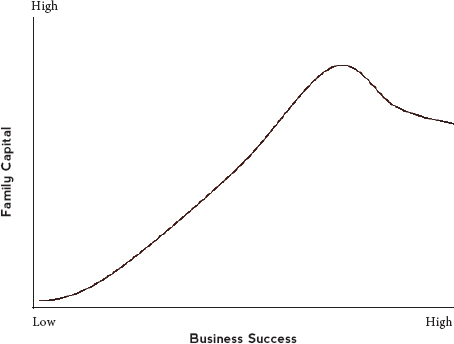

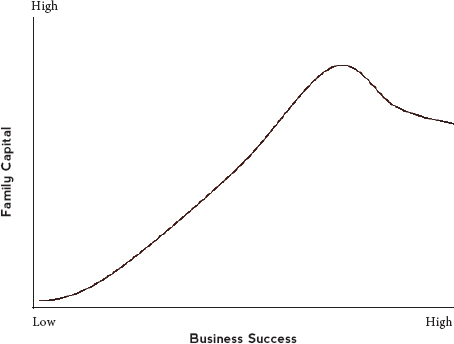

To obtain a more comprehensive view of entrepreneurial success for each youth in the study, we performed what is called “latent profile analysis” (LPA), which helped us identify “clusters” of entrepreneurs based on various criteria of success.26 Rather than use a simple unidimensional measure of success (for instance, “annual income”), which many entrepreneurship studies employ, our clustering allowed us to identify seven unique groups of youths based on the following three criteria: the number of businesses started by the youth by the year 2010, the number of weeks the youth was self-employed from 2000 to 2010, and self-employment income from wages and business profit from 2000 to 2010. Thus, by our measures of success, youths who launched fewer businesses that fared poorly and survived for only short periods were less successful than those who started more enterprises that experienced significant growth over longer periods. The characteristics of the various clusters and their entrepreneurial outcomes are found in table 1.1 (on the following page) and here, in a more graphical representation, in figure 1.1.27

Figure 1.1 The Relationship Between Family Capital and Business Success

Table 1.1 Comparative Advantage of Family Capital of NLSY Youth from 1997 to 2010

*Number of competitive advantages in family capital over another cluster: Low—1, Medium—2–3, High—4–6, Very High—7

Cluster 1 youths are those who were non-entrepreneurs—those who didn’t start a business (#1). This cluster represents 76 percent of the entire sample.

Cluster 2 (6.5 percent of the total sample, 27 percent of the entrepreneurs) I labeled as struggling entrepreneurs (#2). These individuals were self-employed for an average of only forty-six weeks and started an average of 1.26 businesses, with total mean income at $27,460. In short, these entrepreneurs were not successful.

Cluster 3 (6.1 percent of the sample, 25 percent of the entrepreneurs) youths fit the profile of a seasonal entrepreneur (#3). They started exactly one business, were self-employed for about three months (a typical summer vacation period), and made a reasonable income ($14,478) for the time they were self-employed.

Cluster 4 (4.9 percent of the sample, 20 percent of the entrepreneurs) youths were called short-term entrepreneurs (#4) since they were self-employed for just over two years. They started an average of one and a half businesses and made an average of $886 per week, or about $46,000 per year (or $97,155 total self-employment income).

Cluster 5 (3.5 percent of the sample, 15 percent of the entrepreneurs) was labeled successful entrepreneurs (#5). They started 1.77 businesses on average and were self-employed for almost four years (195 weeks). Their average weekly income was $1,765 making an average annual income of $91,780 for a total income of $344,753 while they were self-employed.. Thus they made almost twice as much annually as the short-term entrepreneurs.

Cluster 6 (1.9 percent of the sample, 8 percent of the entrepreneurs) was comprised of what we called star entrepreneurs (#6). They started 1.83 businesses on average and were self-employed for over six and a half years—they had significant staying power. Average weekly income was $5,566 making their average annual income $289,432 ($1,917,505 average total). Such an income suggests that they were highly competent in the role of a self-employed entrepreneur.

Cluster 7 (1.1 percent of the sample, 5 percent of the entrepreneurs) youths were designated superstar entrepreneurs (#7). They started fewer businesses (1.36) than clusters 4, 5, and 6 and were self-employed for a significantly shorter time period than clusters 4–6 (only 70.2 weeks). However, they generated significant wealth in this short time span—$21,525 per week or about $1.5 million in income for being self-employed for less than a year and a half. Thus they fit the profile of entrepreneurs who found “hyper-growth” businesses.

After identifying the youths in each of the seven clusters and identifying their access to family capital, we found the following:28, 29

» Youths with no statistically significant comparative advantage in family capital don’t start businesses. The data clearly show that family capital does matter when one contemplates starting a business.

» Youths who launch a business but rated “low” in family capital are likely to fail (i.e., cluster #2).

» Family capital gives youths a comparative advantage in the success of their businesses. Youths with a medium to high comparative advantage in family capital fared better.

However, table 1.1 also shows that highly successfully youth entrepreneurs—#6, star entrepreneurs, and #7, superstar entrepreneurs—had fewer advantages in family capital when compared with clusters 3, 4, and 5. Clusters 6 and 7 represent a small subset of the youths (only 3 percent of the entire sample and 13 percent of the entrepreneurs), and I suspect these highly successful entrepreneurs, while having some advantages in family capital, may also have found resources outside their families to help their businesses grow rapidly. For example, in 2016 my son-in-law Denver Lough left his plastic-surgery residency at Johns Hopkins Hospital to start his biotech company, PolarityTE, and needed millions of dollars to launch the business. Because our family and Denver’s family didn’t have that kind of money, he turned to venture capital funding. However, I did introduce Denver to my brother Jeff, a strategy professor with contacts in the venture capital industry, who helped connect Denver with venture capitalists and also helped prepare him to make presentations to the venture capitalists to get funding. Denver also turned to his wife—Mary, my daughter—to help him launch the business since she has a background in the medical field. My daughter Christine and her husband, Peter, have also worked for the firm in a legal/human resource role and a facilities management role, respectively. Thus, PolarityTE was started with both family capital and external funding and support. In the case of rapidly growing businesses that need resources over and above what the family has to offer, we’re likely to see a mix of family and external resources that determine business success. But again, these types of firms represent a small minority of the start-ups (13 percent). The vast majority of successful start-ups (60 percent) had significant family resources to draw upon.

Our study of entrepreneurship among America’s youth points out the importance of family capital to youths who want to start a business. Those youths who had well-educated, supportive parents with a knowledge of business and who also had family members willing to lend them money appeared to be best prepared to launch a business. After they started their businesses, those youths who had access to family capital performed better over time. Thus, our study, which is highly representative of the youth of America, emphasizes the importance of family capital for business start-up and success.

Family capital also plays an important role in one’s family, unrelated to starting a business. For example, in one family, which we’ll call the Thomas family, John Thomas felt he wasn’t progressing in his career at the high-tech company where he worked. His father, while discussing the situation with his son, noted that his good friend had just started a high-tech company and needed someone with John’s skills. John’s father helped set up the interview with his friend and John was eventually offered the job. John needed to relocate several hundred miles for this new position, so family members helped John and his wife Erica pack up and move (John’s parents also helped him with moving expenses) and John’s brother offered to let John and Erica stay with his family while they looked for a new home. After several months of living with John’s brother and saving up money for a down payment, John and Erica found an ideal place to live and shortly thereafter had a baby girl, Jean. John’s mother now watches Jean several days each week so that Erica can continue working and also help provide for the family. In John’s case, his family’s human, social, and financial capital didn’t help him start a business, but contributed to a much better financial position and career path. And as John and his family build their family capital over time, they will similarly be able to help other family members.

As I began writing this book I wondered how much family capital the Dyer family has. Do we have “sufficient” human, social, and financial capital to help family members in time of need or help them start a business? Does my family have ways to talk about family capital and share it if needed? So I created a survey to help assess the ability of a family to create and preserve family capital. This survey is included at the end of this chapter.

Chapter Takeaways

» Family capital is composed of the human, social, and financial capital in a family.

» Family capital is generated when family units are created, children are born, and there are stable family relationships.

» Family capital is important for business startup success and family members’ well-being.

Survey 1: Family Capital Inventory

1. How many people do you know personally whom you consider to be family members (including extended family)?

0-10 |

11-30 |

31-60 |

61-100 |

101+ |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

2. How many hours do you spend each week interacting with family members?

0 |

1-10 |

11-20 |

21-50 |

51+ |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

3. In general, to what extent do you consider your family members to be well-educated (include both formal and informal education)?

Not well educated |

|

Highly educated |

||

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

4. To what extent do your parents or other family members have experience in operating a business or are in a career similar to yours?

Very little extent |

|

To a great extent |

||

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

5. To what extent does your family have a positive reputation?

Very little extent |

|

To a great extent |

||

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6. To what extent does your family help family members by sharing knowledge or social contacts, or providing labor (e.g., helping a family member to move)?

Very little extent |

|

To a great extent |

||

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

7. To what extent do you feel emotional support from members of your family?

Very little extent |

|

To a great extent |

||

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

8. To what extent does your family have resources (i.e., money, a home, computers, vehicles, tools, work space, equipment, etc.) that could be used to start a business or support a family member in need?

Very little extent |

|

To a great extent |

||

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

9. If you needed to buy something that was very important, to what extent would a family member (or family members) be willing to loan you the money?

Very little extent |

|

To a great extent |

||

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

10. Approximately how much, in total, could you potentially borrow from family members for something very important to you?

$0 |

Up to $1K |

$1K-$15K |

$15K-$50K |

$5oK+ |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

Scoring: Add your scores from each of the ten questions. The following totals approximate where your family is in terms of family capital.

» 41–50 High degree of family capital

» 31–40 Moderately high degree of family capital

» 20–30 Moderate degree of family capital

» <20 Relatively low degree of family capital

1. Self-employment rates among the various racial groups have fluctuated slightly in recent years, with Hispanics making some gains. However, Asian Americans still create the most successful new businesses.

2. Robert W. Fairlie and Alicia M. Robb, Race and Entrepreneurial Success (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2008).

3. D. Kelley, S. Singer, and M. Harrington, Global Entrepreneurship Monitor: 2015–16.

4. R. J. Samuelson, Washington Post, October 8, 2017.

5. J. D. Harrison, “The Decline in American Entrepreneurship—in Five Charts,” (February 12, 2015), https://www.washingtonpost.com.

6. Mary Eberstadt, How the West Really Lost God, (West Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Press, 2013).

7. S. M. Danes et al. “Family Capital of Family Firms: Bridging Human, Social, and Financial capital,” Family Business Review 22 no. 3 (2009): 199–215.

8. To examine how different races approach child-rearing to develop human capital in a family see A. Lareau, Unequal Childhoods: Race, Class, and Family Life (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2011).

9. Fairlie and Robb, Race and Entrepreneurial Success.

10. Company website is www.kongogumi.co.jp.

11. Fairlie and Robb, Race and Entrepreneurial Success, 179.

12. Fairlie and Robb, Race and Entrepreneurial Success, 92.

13. Thomas M. Zellweger et al., “Building a Family Firm Image: How Family Firms Capitalize on Their Family Ties,” Journal of Family Business Strategy 3 (2012): 239–250.

14. Marc-David L. Seidel, Jeffrey T. Polzer, and Katherine J. Stewart, “Friends in High Places: The Effects of Social Networks on Discrimination in Salary Negotiations,” Administrative Science Quarterly 45 no. 1 (2000): 1–24.

15. W. Gibb Dyer Jr., “Examining the ‘Family Effect’ on Firm Performance,” Family Business Review 19 no. 4 (2006): 253–273.

16. Parade Magazine, May 2, 2010.

17. David G. Sirmon and Michael A. Hitt, “Managing Resources: Linking Unique Resources, Management, and Wealth Creation in Family Firms,” Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice 27 no. 4 (2003): 339–358.

18. Francis Fukuyama, Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity (New York: Free Press, 1995).

19. Timothy Bates, Race, Self-Employment, and Upward Mobility: An Elusive American Dream (Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 1997).

20. United States Census, 1987.

21. Fairlie and Robb, Race and Entrepreneurial Success, 107.

22. W. Gibb Dyer, Elizabeth Nenque, and E. Jeffrey Hill, “Toward a Theory of Family Capital and Entrepreneurship: Antecedents and Outcomes,” Journal of Small Business Management 52 no. 2 (2014): 266–285.

23. Manfred F. R. Kets de Vries, “The Dark Side of Entrepreneurship,” Harvard Business Review 63 no. 6 (1985): 160–167.

24. Prior studies have typically relied on data from the Survey of Businesses Owners (SBO), the Characteristics of Business Owners (CBO), the Survey of Minority-Owned Business Enterprises (SMOBE) and the Current Population Survey (CPS). These studies typically looked at entrepreneurs after they started their businesses thus biasing the sample toward those who have already chosen an entrepreneurial career.

25. J. K. Vermunt and J. Magidson, “Latent Class Cluster Analysis,” in Applied Latent Class Analysis, eds. J. A. Hagenaars and A. L. McCutcheon (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002): 89–106.

26. As control variables we included the youths’ age, marital status, gender, education, and race as well as the industries in which the youths started their businesses and whether or not their parents were divorced.

27. Once the clusters were identified, multinomial logistic regression was used to examine the predictors of the various classes and thus enabled us to include proper controls into the models. To determine the number of unique clusters, various fit statistics were examined to see what number of clusters best fit the data. The most common fit statistics are the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), the sample-size adjusted BIC (SABIC), and Akaike’s information criterion (AIC). The lower these numbers, the better the model fits the data. These analyses examine at what point adding additional clusters decreases the model fit. In addition to examining these fit criteria, we also examined the clusters to determine if they were conceptually distinct from each other. LPA fit statistics may indicate a model fits better with an additional cluster; however, the additional cluster may simply represent the tail end of another cluster and not actually be categorically distinct. We examined the fit of models specifying from one to nine clusters. In examining fit statistics, we found that for each fit statistic (BIC, SABIC, and AIC) at no point did the model worsen with the addition of clusters (not uncommon when dealing with large amounts of data). However, after the six-cluster model, model fit improved only minimally (< 2 percent) with each additional cluster, though it was found that adding the seventh cluster added a conceptually distinct group.

After creating the seven clusters, additional cluster sizes were less than 1 percent of the sample. In addition, the eighth and ninth clusters are likely the tail end of the seventh cluster. These two clusters were apparently “broken off” of the seventh cluster (i.e., when adding the eighth and ninth clusters, the size of all the other clusters remained unchanged except for the seventh cluster, which was reduced by the size of these two clusters). Given that the eighth and ninth clusters were less than 1 percent of the sample and represented the extreme tail-end of the highly successful entrepreneurs, we determined not to retain them as unique clusters but kept them subsumed within the seventh cluster. The seven-cluster solution was therefore designated as our final model.

The seven-cluster solution fit the data very well. For LPA, determining the degree of uncertainty in classifying individuals is important. Entropy is a common measure of this, ranging from 0–1, with values closer to 1 representing fewer errors in classification. Although .8 is often considered an acceptable value, the seven-cluster model had an entropy score of .98 representing a very small amount of uncertainty in classification. In other words, the seven-cluster model was able to classify individuals in the sample with a high degree of accuracy.

28. We used a multinomial logistical regression technique and compared each of the seven clusters to one another to see if there was a statistically significant difference between the clusters.

29. To test our hypotheses we conducted a multinomial logistic regression where cluster membership was the outcome (i.e., an unordered categorical variable representing which cluster each participant belonged to) and each of the predictors were independent variables. Thus, we could examine how each predictor related to cluster membership (i.e., cluster membership was the dependent variable) while controlling for all of the other predictors. To compare each cluster with each other cluster, the base category was simply switched. Thus, we needed to run the multinomial regression six times, each specifying a different base category.

Our initial hypotheses were generated without the benefit of knowing the detailed descriptions of the seven clusters—it is difficult to predict a priori how many clusters will be generated and their distinguishing characteristics. However, our hypotheses were tested via paired-comparison analysis with a more nuanced understanding of the data given that we compared each cluster with all of the other clusters related to the hypotheses we were testing.

Those economies that will advance most rapidly will tend to have strong family structures.

Gary Becker, Nobel Prize-winning economist