CHAPTER 7

HOW DO WE TRANSFER FAMILY CAPITAL TO THE NEXT GENERATION?

A s a doctoral student at MIT in the early 1980s, I was the teaching assistant to Professor Dick Beckhard, a well-known business consultant and a friend of my father (again the advantage of family social capital). One day, when I was eating lunch with Dick, he asked, “Gibb, what do you know about family businesses?” I admitted that I didn’t know much about them, only that my grandfather ran a family-owned grocery store in Portland, Oregon, for many years and that my great-grandfather operated a family business with his sons in Alberta, Canada. Dick explained that many of his clients owned family businesses and were extremely difficult to work with. He would try to help his clients solve various business issues only to have family conflicts and dynamics undermine his consulting work. He then proposed that we invite some of his clients to Boston, listen to their problems, and develop a research agenda based on family business issues. When Dick’s family business clients arrived, I spent three days learning about situations I never encountered in my MBA program, which had focused primarily on challenges facing large, public corporations. Although the clients discussed family conflicts, nepotism, the role of nonfamily managers in family firms, and such, the issue that most concerned them was succession in the family business—the transfer of ownership, management, and values from one generation to the next. Since that time, I have researched and consulted about the succession problem. Transferring family capital to the next generation poses difficulties most families do not handle well; conflicts between and within generations can lead to poor outcomes. Poor estate planning often results in paying too many taxes or leaving wealth to the wrong people; a lack of planning for the transfer of family capital across generations can lead to a loss of that capital, leaving future generations deficient.

Given these challenges, in this chapter I will discuss problems related to the issue and outline a process I believe can help. A checklist at the end of the chapter will help you determine your family’s situation.

For some families, the transfer of family capital to the next generation proceeds naturally. Because of the culture, family elders teach their children or other younger family members what they need to know to succeed in life and imbue them with values they believe will be helpful. Moreover, the family leaders look for opportunities to provide experiences for younger family members whether through full- or part-time employment, internships, traveling to gain experience, or working on projects together. Family leaders often foot the bill or give their time for these experiences, making it easier for the younger family members to participate. Certain wealthy families also provide support to future generations through trusts or other mechanisms that provide financial resources to help family members launch successful careers.

Unfortunately, in my experience, families that successfully transfer family capital to the next generation are in the minority. Evidence of the lack of planning for transferring family capital can be seen in the number of people that have created a will—the primary mechanism to transfer financial wealth to the next generation. According to a recent survey, 51 percent of Americans age fifty-five to sixty-four do not have a will (moreover, 68 percent of African American adults and 74 percent of Hispanic adults in that age group have not drafted that important document).1 Although some families have wills to transfer family financial capital, I find that even fewer have plans to transfer family human and social capital to the next generation. Those types of capital can be even more valuable than tangible resources.

Several reasons explain why family elders fail to plan for the transfer of family capital, including the following more common ones.

A number of clients have told me they think the act of creating a will or doing succession planning is akin to “planning my own funeral.” Most of us do not want to think about death. One of the family leaders that I met in the Boston meetings gave the following analogy to illustrate the depth of his feelings about succession planning:

Succession planning . . . is really digging your own grave. It’s preparing for your own death and it’s very difficult to make contact with the concept of death emotionally. . . . It is a kind of seppuku—the hara-kiri that Japanese commit. [It’s like] putting a dagger to your belly . . . and having someone behind you cut off your head. . . . That analogy sounds dramatic, but emotionally it’s close to it. You’re ripping yourself apart—your power, your significance, your leadership, your father role.2

While not all of us have such deep, negative feelings regarding planning for a future where we are not in the picture, such feelings are common and can prevent creating a plan to transfer family capital to the next generation.

One common characteristic of family firm owners that I have worked with is the tendency to be secretive and avoid sharing resources with others. The knowledge, contacts, and financial resources held by family leaders gives them the power and status that they need (and sometimes crave) to influence others and get things done. Giving that up by sharing information, contacts, or other resources can cause much discomfort. Family elders may want to always have a “one up” on others in the family, particularly their children or others in the next generation, so there is little incentive to share with them.

All of us want to be seen as a valuable contributor to our families and to society. Unfortunately, some see retirement and handing over the reins of leadership to the next generation as diminishing their sense of worth and value to the family and to society. One family business leader said the following:

I could [not] care less about retiring. The guys that I know that are successful and do well are the ones who never retire. . . . A good way of dying fast is going from being busy to doing nothing. I don’t think I’ll ever stop working. . . . I’d rather have something to do to keep me busy. Otherwise, I’d go nuts. You can’t just get in a rocking chair and waste your life away.3

If family elders see the transferring of family capital to the next generation as diminishing their usefulness and role in the family, they are less likely to do so.

I have found numerous family leaders who are reluctant to transfer their family capital due to lack of confidence in their progeny. Some see an entitlement mentality in the next generation and believe their heirs to be irresponsible and likely to squander the resources. Their concern is not unreasonable, since several studies of family businesses have found that second and third generations are often poor stewards of family resources—and as a result the family firm does poorly or goes bankrupt.4 One study by the Williams Group reported that 70 percent of wealthy families lose their wealth by the second generation and 90 percent by the third.5 The survey further noted that 78 percent of the respondents didn’t think that the next generation was prepared for an inheritance, and therefore 64 percent had shared little or no information about the status of their wealth with their heirs.6 Some wealth advisors have been overheard saying, “The first generation makes it, the second spends it, and the third blows it.” Thus, if there is little trust in the next generation, there is little incentive to plan for the transfer of family capital.

Many do not understand how to transfer capital or even that they need a plan. Whereas informal sharing in the home happens spontaneously, transferring key knowledge and skills often happens only with planning—particularly if a family wants to maintain social relations with those who can help them. Maintaining strong social ties to important people across generations should not be left to chance. Yet I find that many family businesses flounder after a leader is incapacitated or dies suddenly, because he has not helped the next generation join the social network.

When family leaders fail to transfer family capital, the outcomes can be devastating. One wealthy business owner died unexpectedly without preparing for the transfer of important knowledge and social contacts. His son reflected on what a severe blow it was to him and his family:

On the day of my father’s funeral, the family had to go to his office and break into the locked bottom right drawer of his desk. He always said if something happened to him, that was where the important stuff was. You don’t know how many times I later sat at that same desk crying, wishing my father had spent an hour with me explaining what it all meant. The professional advisors tried to be helpful, but I just didn’t understand the relationships. . . . Sure, I had worked in the firm for a couple of summers doing office stuff, but it was primarily secretarial and I really didn’t pay much attention to how the business was really run, who the key players were. I could have learned more. People could have taught me more. . . . We simply weren’t prepared for his passing—on the home front or the business front.7

Unfortunately, this situation is all too common.

Sometimes family capital is transferred, but younger family members are unprepared to handle the responsibility—particularly financial capital. One successful founder confided in me that she felt her children weren’t prepared and were ill-served when she had to sell her company unexpectedly. Her children had received gifts of company stock, making them instant millionaires. She explained:

The number one change that we would make today, had we known that we were going to sell the company, would be to not give our children 49 percent of our business in stock. Our children would first have to earn their own money, get an education, go into careers of their own choice, buy their first homes, struggle to buy their furniture, have direction, and accomplish goals. To actually know the thrill of what it is to achieve success on their own. We feel that this is an area that we as their parents totally lost control of and that we have done a big disservice to our children. And it is a big concern to us. Of course, they would be shocked at hearing me say this. They are thrilled to have this wonderful opportunity to have new houses, to go golfing every day, to be able to do whatever they want. But they received too much money too soon, and it could really be a curse to them in the future. . . . They will never know or understand the true value of achievement.8

One of my most significant challenges has been to motivate family leaders to transfer family capital. The noted psychologist Erik Erikson describes generativity, his term for that which motivates individuals to be concerned about the well-being and success of the next generation.9 Erikson believes that most people have a concern about leaving a legacy—the need to leave their mark on the world—which emerges toward later stages in life. People generally see that they can preserve their legacy through their children or other family members. Generativity can impel them to begin transferring family capital to their heirs.

Nevertheless, my clients are often not motivated until a health crisis or dangerous experience causes them to face death. I have always wished for some ethical way to give my clients a near-death experience to encourage them to change. Unfortunately, I haven’t figured out how to do that yet.

A more practical approach that I have used is to get them involved in organizations such as the Young Presidents Organization and their local chamber of commerce, where they can meet people like themselves who have faced or are facing the challenge of passing on their wealth. Listening to stories of success and failure from others in a similar situation tends to help my clients see the value of preparing their descendants for a future without them. I also share with them the sad statistics regarding the performance of the business and the health of the family when family leaders don’t prepare the next generation of leaders.10 Despite my best efforts, I still experience failures in helping family leaders develop and carry out a succession plan.

Transferring family capital requires the family to answer the following questions:

» What kinds of family capital (human, social, financial) will be helpful to future generations?

» What family capital do we currently have that needs to be transferred?

» Who has access to this family capital? Or, if we don’t have the needed family capital, how do we develop it for future generations?

If family leaders don’t start the process, younger family members may need to bring these issues to the attention of their elders, since months or years may be needed for the transfer of family capital. Raising these issues is not easy, because the elders may view the younger generation unfavorably. No one wants to be seen as a gold-digger or as someone who wants to hasten a parent’s demise. This is when high levels of trust—discussed in the previous chapter—should smooth the process.

To facilitate the process of transferring knowledge, skills, and social contacts, doing the following is useful:

1. Create a genogram of one’s nuclear and extended family.

2. Create a family capital genogram that identifies who has access to family capital.

3. Develop a plan to improve relationships between those who have family capital and those who need it.

4. Develop specific plans to transfer family capital from one person to another by using the “learning by doing” approach, which sometimes requires getting outside help (e.g., lawyers, accountants).

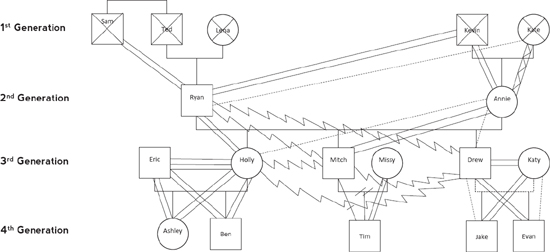

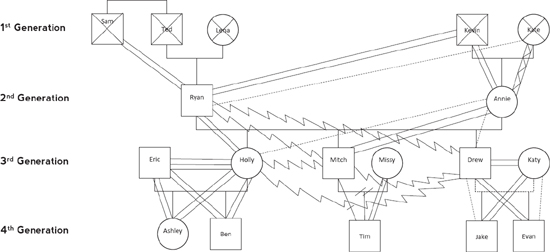

Family genograms are a diagnostic tool to help families understand how their family functions.11 Figure 7.1 is a genogram of the hypothetical Williams family. I have listed four generations, although in most cases three is sufficient. In figure 7.2 are listed the various symbols found in the genogram and what they mean.

In figure 7.1 the squares designate men and the circles designate women. An “x” through either a square or circle denotes that the person has died. For the Williams family, all of the individuals listed in the first generation have passed away. In the second generation, Ryan and Annie are married and have a “typical” relationship—neither close nor distant. Ryan had a close relationship (two lines between people) with his Uncle Sam, while Annie had close relationships with her father and mother, though the latter was fraught with conflict (as noted by the lightning symbol). Ryan has a close relationship with his daughter Holly but has had significant conflicts with his two sons, Mitch and Drew. Annie has distant relationships with Holly and Drew (as noted by a dashed line) but a close relationship with her son Mitch. In the third generation, Eric and Holly—who are married—have a “fused” relationship (three lines between them), meaning that one generally doesn’t do anything without the other’s input and consent. Moreover, Eric and Holly have a close relationship with their children Ashley and Ben, who have a close sibling relationship with one another. Mitch and Missy, on the other hand, are divorced (noted by two diagonal lines between them). As a result, Mitch’s son, Tim, has cut off their relationship (noted by one diagonal line between them)— they haven’t communicated with each other in several years. However, Missy—Tim’s mother—has a close relationship with him (Missy had sole custody of Tim after the divorce). Drew and Katy are in a close, cohabiting relationship (a dotted line like those who are married) and have two sons together. Drew has a close relationship to Evan but a distant relationship with Jake, while Katy has just the opposite relationships with the boys—close to Jake but distant from Evan. Jake and Evan have a distant relationship.

Though not depicted in the Williams genogram, families whose members have serious physical or mental challenges should denote that by shading the left side of the appropriate circle or square, while families whose members have substance abuse challenges should denote that by shading the bottom part of the related figure. Because such individuals often need significant family resources to help them with their challenges, they should be represented.

Figure 7.1 Williams Family Genogram

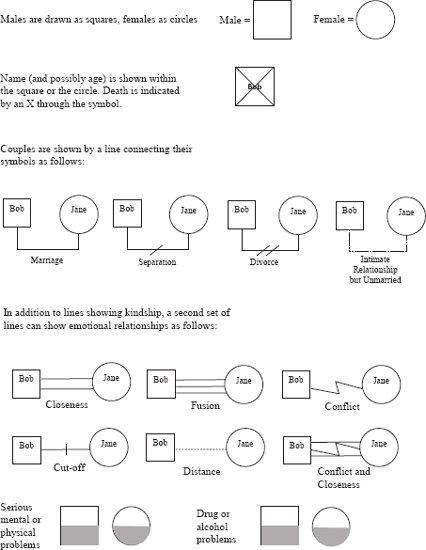

Because family capital is generally not transferred when the relationship is conflicted or missing, a genogram provides insight relevant to the transfer. Once the initial genogram is created, a family capital genogram can be constructed (see figure 7.3). To do so, one determines the human, social, and financial capital held by each person. In figure 7.3, human capital is designated by “HC,” social capital by “SC,” and financial capital by “FC.” One asterisk (*) designates modest family capital on that dimension, two asterisks (**) medium capital, and three asterisks (***) means that the person is high on that particular dimension. If HC, SC, or FC are not listed next to a person’s name, that indicates no significant family capital along that dimension. Those creating the family capital genogram should develop a list for each person that specifies the relevant human, social, and financial capital. For example, if Holly has a particular social network, the people in that network should be identified along with what could potentially be gleaned from each; or if Annie is known to have $2 million in liquid assets, that should be listed.

Family Capital Designations

HC—Human Capital |

*Low |

SC—Social Capital |

**Medium |

FC—Financial Capital |

***High |

No * indicates little or no family capital. |

|

Figure 7.3 Williams Family Capital Genogram

In the case of the Williams family, Ryan’s Uncle Sam has a rich social network, even though he is dead. But that network can still be valuable. In my case, I can call on friends of my father to provide advice and help even though he has been gone for more than twenty years. In the Williams family, Ryan is the conduit through which Sam’s relationships flow; for someone in the Williams family to connect with this social network they would typically need to have a good relationship with Ryan. Thus Holly—Ryan’s daughter—might gain access to Sam’s social network, whereas Mitch and Drew would likely need to repair their relationship with their father to gain access (although a family member could perhaps go around someone in the family to access his or her network). Figure 7.3 also shows that Annie had close relationships with her parents, but neither one has significant family capital. However, Annie has significant human, social, and financial capital. Because of Mitch’s close relationship with his mother, Annie, he is likely to be able to draw upon her rich resource network, whereas Holly and Drew probably won’t be able to influence their mother to help them if a need were to arise. Eric and Holly’s family members would likely share family capital with one another, since they have close relationships and could help one another; both Eric and Holly have significant family capital and their daughter Ashley has access to social capital. Tim likely won’t be able to go to his father, Mitch, for help, but his mother Missy’s social network is available to him. Due to Drew’s conflicted relationship with his father, Ryan, and a distant relationship with his mother, Annie, he will likely not be able to draw upon resources from either. However, his partner, Katy, has important social and financial capital that could be useful to him. Jake could tap into Katy’s resource network while Evan could tap into Drew’s resource network, particularly along the dimension of human capital.

After creating the family capital genogram the next step is to strengthen relationships between those in the family who have family capital and those who need it. Building trust between family members is the key to creating stronger family relationships. See chapter 6 for how to repair breakdowns in interpersonal trust, how to develop competence trust, and how to build institutional trust through being more transparent. In the Williams family the cut-off relationship between Mitch and Tim would likely not be repaired without therapy.

Over my career as a consultant and educator, I have learned that merely providing my clients and students with information can only get them so far. It’s the application of that knowledge in the real world that leads to real learning and positive results. One principle I have learned in helping families transfer family capital is to make them earn it! Family capital should not just be given to a person—even though it is relatively easy to transfer money versus transferring social contacts or skills. The recipients of the family capital need to engage in learning that allows them to intimately understand the nature of what they receive.

I have found the “learning by doing” approach to be the most successful method to transfer family capital. The person transferring the family capital would need to identify the type of family capital and potential learning experiences that will help the person acquire and use the family capital effectively. Typically, the person transferring the family capital will mentor the recipients during the process.

J. Willard “Bill” Marriott, founder of the Marriott Corporation, and his parents, Will and Ellen, exemplify my point. At age fourteen, Bill was asked by his father to take a herd of sheep from Ogden, Utah, to San Francisco, California, by train (a distance of about 800 miles); sell them; see the world’s fair that was being held there; and then return safely. Bill Marriott’s biographer, Robert O’Brien, tells the story about this event:

A moment that he had never even dreamed of arrived in March of 1915. It had been a good winter for the farm, and Will and the lad were playing checkers one evening in the sitting room after supper.

Will, now about fifty, bent his huge frame over the board and pondered his next move. Ellen sat in a rocking chair reading the newspaper by the light of a kerosene lamp on the table beside her chair. There was a hint of spring in the air, and through the screened and open window drifted the cries of the other youngsters and their friends playing hide-and-seek in the valley dusk.

“Son,” Will said, “there’s something mighty big going on out in California. Have you heard anything about it?”

Bill thought he knew what his father meant, but he hesitated.

Ellen lowered her paper. “Course he has, haven’t you, Bill? There’s a story about it right here in the Standard.”

“I reckon I know what you’re talking about,” the boy said. “They’re having a big world’s fair out there in San Francisco.”

Will made his move, then leaned back in his chair. “That’s right.” He studied his son for a moment. “How’d you like to go out there for a few days—see the fair and what some of the rest of the world looks like?”

Bill sat stunned. Sure, he’d been to Star Valley in the Buick and to Salt Lake City, and down to Provo once or twice—but San Francisco, where the trains went? The Pacific Ocean?

He swallowed hard. “Who—me?”

Ellen swung her paper aside. “Not if I have anything to say about it.”

“That’s right,” Will said. “What I’ve been thinking is this. We’ve had a good spring with the sheep—two or close to three thousand of them ready for market. Now, out there in ’Frisco, they’re running a big exposition all summer long to celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal. There’ll be thousands of visitors every day. The restaurants will be needing lots of meat and vegetables and supplies, maybe double what they usually buy. Our lambs will bring a good price, better than Salt Lake or even in Omaha.”

The boy couldn’t believe it. “And you—you want me to take them there—on a train?”

“Nothing to it,” Will said. “We’ll herd them up to Ogden, drive them onto the cattle cars, close the gates, and hook ’em up to a train going to ’Frisco.”

Bill still couldn’t believe it. “Where—where will I ride?”

His father laughed. “Where will you ride? In the caboose, with the crew. You’ll be right up there where those little windows are, looking out over the countryside as you go by and learning something about this land of ours.”

Ellen shook her head. “Will, that’s downright irresponsible. It’s putting much too big a load on the boy’s shoulders—sending him off nearly a thousand miles to a strange city with thousands of sheep, when he’s never been away from home before. What if he gets lost, or gets hurt—?”

The boy looked down at the board. His heart was pounding, and he never forgot what his father did next. The older man stood up, picked up his chair, and carried it over to Ellen’s rocker. He sat down and took Ellen’s small, work-worn hands in his big ones and looked into her eyes. “Ellen,” he said, “Bill’s not a boy anymore. He’s a young man. For the past few years now, I’ve been busy with the church and with politics and everything. Maybe there’s a lot of things I should have done that I didn’t do. But young Bill’s stood in for me and taken my place, just like a grown man. He’s taken care of the barns and the beets. He’s raised lettuce and made us a lot of money. He’s taken care of the other children and you, while I’ve been away. He’s ridden herd. Why, he’s even shot a couple of bears. What other youngster in the whole valley has done that?”

He looked over at the boy with trust and confidence. “This’ll be like rolling off a log for Bill. All we have to do is put those sheep on the cattle cars, and they’re locked up. A couple of days on the road, and he’s there. And all he has to do on the way is see that those sheep don’t fall all over themselves when the train comes to a stop for water or pulls off on a siding to let the express trains pass. I’ll give him a long prod pole to take with him, so he can poke ’em up off the floor. That’s all there is to it. Ellen, I’d trust him with my life and so would you. Sure as anything, we can trust him with a flock of sheep”.12

In today’s world many parents wouldn’t trust their fourteen-year-old son to pick up a gallon of milk at the local grocery store and bring it home, let alone have him take several thousand sheep by train hundreds of miles from home—and with no cell phone to check in! But Will knew that his son needed experience outside of their small farming community and needed the skills related to shipping and selling sheep in order to eventually become an effective farmer. Will had developed an implicit trust in his son—whatever Bill was tasked to do, he did. By the age of fourteen, Bill had already learned how to run the farm, raise crops, help with his siblings, and even shoot a bear—so he had already developed a strong skill set needed on the farm and had developed a sense of self-reliance. And in addition to building the human capital skills of shipping and selling sheep, through this experience Bill would begin to develop a social network. He would interact with people who could help him ship a herd of sheep and— more important—develop relationships with key customers. Thus, it’s not particularly surprising that with the business and entrepreneurial skills that Bill learned from his father while growing up on the farm, he was able to launch one of the most successful hotel chains in the world, and help his own children gain the skills they needed to grow the business after he retired.

A variety of approaches are used by families to help transfer family capital using this learning-by-doing approach. For instance, I’ve seen some family leaders identify formal training—apprenticeships, technical programs, or college degrees—that will help the next generation develop the skills and experience they will need. Family leaders may also work with the next generation on projects or in a business to mentor them. For example, before transferring money to the next generation, a family leader might require the son or daughter to find a job, earn money, and make and keep a budget for a period to demonstrate responsible use of finances. To facilitate this learning, the family leader then provides support for younger family members by helping them in their job searches and teaching them how to manage money and live on a budget.

Recall my previous discussion about how Jon Huntsman took his son Peter (future CEO of Huntsman Chemical) on business trips to help Peter understand how the business worked and to build relationships with key company employees. More importantly, Peter started near the bottom of the organization as an oil truck driver. This allowed Peter to understand the business from the bottom up; demonstrate his competence at various levels in the company; and—most important— begin to develop a social network that, when coupled with his father’s social network, would help him in his future role as CEO.

In most instances, outside help will be needed to manage the transfer of family financial capital. Lawyers, accountants, or both will need to draw up a will and determine the tax consequences of transferring assets between generations. In my family, when the children were younger Theresa and I stipulated that, were we both to die, our children could not access their inheritances until age twenty-five. In our absence, my brother David—and later my oldest daughter Emily— were designated as executors of our will to help protect and manage the assets of those children under age twenty-five. Since all my children have now passed that age, any inheritance will flow directly to them when Theresa and I pass away.

Chapter Takeaways

» Family leaders are sometimes reluctant to pass their knowledge, skills, and contacts to their heirs.

» For those who take the step, they can create family gen-ograms to smooth the process.

» The learning-by-doing approach is the most effective way to transfer family capital.

Family Capital Transfer Checklist

1. Do you have a will that designates who will receive your assets when you pass away?

Yes No

2. Do you have a living will that outlines your end-of-life wishes?

Yes No

3. Do you have a contingency plan to have your assets managed or transferred if you were to die suddenly or be incapacitated for some reason?

Yes No

4. Have you identified the human capital you need to transfer to your family members for them to succeed in the future?

Yes No

5. Have you identified the social capital you need to transfer to your family members for them to succeed in the future?

Yes No

6. Have you identified the financial capital and other tangible assets that you need to transfer to your family members for them to succeed in the future?

Yes No

7. Have you identified who needs to receive the various types of family capital?

Yes No

8. Do you have a plan to transfer family capital to those family members who will need it?

Yes No

9. Does the plan use the “learning-by-doing” approach described in this chapter?

Yes No

10. Do you believe you will be successful in transferring family capital to the next generation?

Yes No

11. Will your legacy be preserved through your plan of transferring family capital?

Yes No

12. Are family members aware of and support your plan to transfer family capital?

Yes No

Scoring: If you answered 9–12 “yes” answers, this indicates that you are well on your way to transferring family capital successfully. If you answered 6–8 “yes” answers, this indicates that you are off to a good start. Fewer than 6 “yes” answers indicates that your family is at risk of losing family capital in the future.

1. “Make A Will Month,” Rocket Lawyer, 2014, https://www.rocketlawyer.com/news.7article-make-a-Will-Month-20i4.aspx.

2. Jeffrey H. Dyer, The Entrepreneurial Experience: Confronting Career Dilemmas of the Start-Up Executive (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1992), 172.

3. Ibid., 171.

4. Belen Villalonga and Raphael Amit, “How Do Family Ownership, Control, and Management Affect Firm Value?” Journal of Financial Economics 80 no. 2 (2006): 385–417.

5. Chris Taylor, “Your Money—A Little Honesty Might Preserve the Family Fortune,” Reuters, June 17, 2015.

6. Ibid.

7. Lloyd Steier, “Next-Generation Entrepreneurs and Succession: An Exploratory Study of Modes and Means of Managing Social Capital,” Family Business Review 14 no. 3 (2001): 259–76.

8. Dyer, The Entrepreneurial Experience: Confronting Career Dilemmas of the Start-Up Executive, 199–200.

9. Erik H. Erikson, Identity and the Life Cycle (New York: W. W. Norton, 1980).

10. Donald B. Trow, “Executive Succession in Small Companies,” Administrative Science Quarterly 6 no. 2 (1961): 228–39.

11. Jane Hilburt-Davis and William G. Dyer, Consulting to Family Businesses: Contracting, Assessment, and Implementation (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer, 2003).

12. Robert O’Brien, Marriott (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1987), 60–63.

The family is one of nature’s masterpieces.

George Santayana, philosopher