Chapter Five

My father was never one to linger over tales of his childhood. I see that now, looking back. If it had ever occurred to me to ask him why, he might’ve said, with a look of amusement, that he’d never given the question any thought. It was just, he’d have said, who he was. In our house, there were photographs of my mother as a child with her parents. We knew about their family camping trip to the Canadian Rockies, and the progressive elementary school to which her mother had wisely sent her, and her childhood friends, and the family dogs, and the French nurse, Marie. Of my father’s early years, we heard fewer details. There was a studio photograph of a towheaded child with a look of impish anticipation, and a picture of him as a boy in the “Alice in Wonderland” garden at Chiltern. We’d heard of the pet dove he won at a church fair, and a horse for whom he’d saved his wartime sugar rations while away at school. We knew that he adored his parents: He said so often when people brought them up. You couldn’t spend time with the three of them and not come away with the impression that the son was as taken with the parents as the parents were with him. I must have assumed I knew the story, since the setting of his childhood, and the cast of characters, overlapped with mine. Only late in his life did it begin to dawn on me that the emotional terrain had been more rugged than I’d understood.

Six months before his death, he let slip a story that none of us remembers hearing. He was speaking to an oral historian, a stranger. I learned of the interview only years later, after his death, when I was given a recording. The opening question was routine, but I was surprised by my father’s answer. Asked where he’d been born, he gave his date of birth and the name of the hospital—then went on to say that his mother had left him there at one day old. She’d delivered her first child at home and would have preferred to do the same for her second. So she agreed reluctantly to hospitalization, then checked out as soon as she could, leaving her newborn in the nurses’ care. Sometime later, an ambulance pulled up at the house in Villanova and dropped off the infant. I’m sure this is a myopically twenty-first-century thing to say, but I can no more imagine voluntarily leaving my healthy, day-old baby behind in a hospital than I can imagine, say, abandoning him or her on the banks of the Tiber to be suckled by a she-wolf.

In keeping with family practice, my father was placed in the care of a French governess. He came to adore her, he said long afterward, while everybody else disliked her “rather cordially.” The summer he turned six, during an extended stay in the Bar Harbor “cottage,” his Scott grandmother unceremoniously canned the object of my father’s devotion, giving neither of them the opportunity to say adieu. (The governess had been venting her aggression, I’m told, by clobbering my father’s older brother, Ed.) From then on, my father passed many days and nights, not unhappily, in the company of his parents’ Irish butler, Irish cook, and Irish maid. (A cousin of my father’s, who spent his early years on Ardrossan, told me, “If there are any redeeming qualities in me, it can be attributed to the fact that I was raised by Irish cooks and maids.”) Years later, my father professed to have spoken English with an Irish accent until the age of nine—“to the consternation of my grandmother Scott who was a Boston Brahmin and did not approve of her second grandchild speaking in the tongue of the people who had taken over Boston from the likes of her family.”

His parents were an intermittent presence. During his first decade, they kept an apartment in Manhattan for proximity to the stock market, the theater, clubs, New York friends. They had a cottage, too, for a time, in the open country to the west of Delaware County, to which the foxhunting crowd was increasingly heading. Piecing together the timeline, it dawned on me, for the first time, that my father was fourteen months old when his parents sailed off to Ireland for their first, month-long encounter with Augustus John. When they left again for Europe the following summer, he’d just turned two. By the time they embarked for London for the third John portrait, he and Ed were old enough to accompany them on the train to New York for the privilege of seeing them off. Back in Villanova, aunts, uncles, grandparents, maids, and cooks pinch-hit. The big house was, my uncle told me without any trace of self-pity, “a resource that was used at such times to ship off the kids and go away.” My father used the same tone—an irony so finely planed as to almost slip by undetected—when he wrote, in his sixties, that his parents “returned from time to time to look after their Philadelphia life, including their horses, their dogs, their donkeys and their sons.”

I study the margin between said and unsaid.

“My mother and father were wonderful parents,” he told a journalist after their deaths. “Enormously kind and caring, in their way.

“But quite . . .”

He hesitated.

“. . . distant.”

He ventured further.

“Unused to children.

“Busy with their own lives, entertaining and so forth.

“But very decent, loving people.”

As a young boy, he had what one teacher called in a report card “considerable social charm.” He was lively, talkative, funny. “Such a personality,” his father marveled. In elementary school, he could be found amusing his classmates instead of attending to the teacher. “Bobby never walks into a room,” his Boston-bred grandmother remarked frostily. “He makes an entrance.” He had an interior quality, however, that his mother diagnosed as a “slight shyness.” Perhaps she passed along to him her own mother’s miracle cure. For, by the time he’d reached adulthood, my father gave every appearance of having absorbed the imperative to “always give people the best possible time.” He seemed to have vanquished whatever surplus of self-consciousness his mother had labeled shyness.

He alone, I now see, knew better.

For all her charm and gifts, Helen Hope had limitations as a parent. She was self-centered, she liked recognition, she was quick to take offense. One of the few episodes from my father’s childhood that my brother, sister, and I all recall him recounting concerned her fury after he, as a small boy, compared her midriff to a wrinkled paper bag. Though she worked tirelessly at many things, that energy and focus came at a price: She was not, it seems safe to say, overly involved in the lives of her sons. In the event of some run-of-the-mill screwup, she could be less than scrupulously honest in assigning blame. Once, after skidding into the side of a stone bridge while driving to the big house with Ed when he was a boy, she took to fulminating against her father—presumably for bridge misplacement thirty years before. Her approach to discipline was tough. “Toilet training was particularly rigorous,” my father wrote in a rare confession many years later, “my mother treating the process like housebreaking dogs.”

He was careful, I now see, in what he said about her.

“I adored my mother, but she was not easy,” he’d say, leaving it at that.

Or, “It was a pleasant existence, if we were careful not to cross my mother.”

Or, “When the light was shining on us, we were very much there. When it wasn’t, we made do.”

In my grandfather’s letters, his pleasure in his sons is evident. “The boys were perfect,” he writes to their mother, after taking them to a baseball game. “I’m always so happy with them, and so proud of them.” Having decided not to wake his youngest to say good-bye as he leaves on a business trip, he’s afflicted with remorse. He sends a telegram to Helen Hope, then a letter. “I’m still worried I may have hurt Bob’s feelings,” he writes. “He’s so nice, I’d hate to.” But my grandfather’s life was busy, too, in those years. Alighting in Pennsylvania for a meeting of the sewer commission on which he’s serving, he recaps the day’s events in a telegram to Helen Hope, who’s also out of town: TOO BUSY OFFICE TENNIS SEWER OPERA WITH MAMMA BOBBY THREW UP SCHOOL LUNCH TODAY FINE NOW DOGS HORSES FINE.

My father didn’t share his mother’s passion for horses. When his brother asked to resume riding at age eleven, having quit at six, she offered him a donkey, not yet broken, to ride for the summer. Come September, they’d see if he was ready for a horse. Ed rode the donkey, bareback, all summer, trailing his mother, who was on horseback, up and down hills. By fall, he had the donkey clearing small jumps—a feat that I take it is not entirely unlike teaching a dachshund to dance. Impressed, Helen Hope gave her elder son a horse. From then on, they rode together, as she passed on to him everything she knew. Once, when a horse she was breaking kicked her in the stomach, she surprised Ed by handing him the horse to complete the job. In a sphere that was central to her life, she and her eldest connected. In a household dominated by the personality and interests of his mother, my father sometimes found himself on the sidelines. He went through, Ed told me, “a sort of wintry period in his youth.”

His maternal grandfather, it seems, left a deep impression on my father. When he dreamed, as a small boy, of living in a palace, the palace in the dream was the Greek Revival temple that the Colonel’s architect, Horace Trumbauer, had designed for the Philadelphia Museum of Art. When, many years later, my father would remember his grandparents’ house, he’d remember the white-gloved, blue-waistcoated footmen—“like something out of a Revolutionary War–themed painting”—and library shelves lined with Kipling and Trollope. Other grandchildren kept their distance from the irascible, oversized, unnerving Colonel, but my father would look back on the Colonel’s fits of temper with fond amusement. He’d remember, with the same indulgence, the Colonel’s practice of piloting private planes after a wine-fueled lunch. “I was the first of his grandchildren to be named after him, and I absolutely adored him,” he’d tell the oral historian who interviewed him late in life. The words he used to describe his grandfather: successful, opinionated, aristocratic. “Wonderfully enough, I was probably his last great friend,” my father said. He’d recall sitting with him after lunch—the older man with his cigar and brandy; the child, age eleven, drinking rum. In his midtwenties, stupefied by the tedium of his newly chosen profession, the law, my father would daydream about writing a novel based on the character of his grandfather.

The two of them understood each other. That’s how my uncle Ed put it.

The Colonel was in his early sixties when my father was a boy. A quarter of a century had passed since he’d built his Xanadu beside Darby Creek. What had become of him in the decades following his heyday was a question I hadn’t considered until I came upon a letter from a former business partner of his, written after the Colonel’s death. “Many times I have tried to figure out what caused the great change in him,” the man confided to my grandfather, the Colonel’s son-in-law and a business partner himself. The change had come on gradually, the man said, through a series of setbacks. In the years immediately after World War I, the Colonel’s partners in the investment banking firm had turned against him. “He was so used to being recognized as the Captain of the ship, which he certainly was, that it was impossible for him to understand how any of us could challenge his leadership,” the man wrote. The resulting dissolution of the firm, in 1921, was a mistake, the former colleague wrote. It had left the Colonel, “a man of action,” becalmed.

There’d been another blow, too—a public humiliation. A month after the United States entered the war in 1917, President Woodrow Wilson had set up a five-man board charged with stimulating the rapid production of three thousand, five hundred military aircraft. My father’s grandfather, appointed to the new Aircraft Production Board because of his experience in finance, was soon in charge of finance for the equipment division of the United States Army Signal Corps, then head of the division, briefly. He was commissioned as a colonel. Congress had appropriated $640 million for the production program; another $840 million had followed. But by the time the war ended in November 1918, the program had failed to generate a single American-built combat plane, pursuit plane, or bomber at the French front. With thousands of trained aviators ready to fly, the United States had had to borrow or buy planes from the Allies. All the aircraft-production program produced was a couple hundred observational planes. Investigations—by Congress, the Department of Justice, and news organizations—traced the debacle to inexperience, errors of judgment, and what the congressional report called “a record of stupidity and stubbornness that involved an inexcusable waste of men and money, and invited military disaster.”

In the letter three decades later, Michael Gavin, the Colonel’s business partner, wrote to my grandfather, “Some called it a scandal, and some demanded criminal prosecution. You can easily understand how that sort of thing would stagger Bob.”

At the height of the uproar, the Colonel summoned his business partner to Washington. Gavin found him “in bed looking tired and worried.” The Colonel had been detached from aviation duty and assigned to cooperate with the Department of Justice in its investigation. Aware that Gavin was acquainted with the new chairman of the aviation board, the Colonel asked Gavin to see what he could learn. The new chairman told Gavin to tell the Colonel that “he thought all the talk about scandal and criminal prosecution would die down and be forgotten,” Gavin wrote. But the scandal, understandably, hit the Colonel hard. “He seemed, after that, to gradually lose some of that boldness and confidence,” Gavin said, “which was a great asset in anything he undertook to do.”

The story of the Aircraft Production Board fiasco wasn’t one I’d heard in the family. I learned of it from the letter, then newspaper archives, then government records. Did the Colonel’s children ever know the details? Did his grandchildren? It was not a descendant but a son-in-law, Edgar, who preserved the lone clue—the business partner’s ruminations on “what caused the great change.” A century later, I’m unable to determine the Colonel’s precise involvement in the crack-up. Was he personally to blame? Or not? Did he belong on that board? Maybe it was perfectly reasonable to appoint a man with experience in industrial finance. All I’m left with is the irony of the Colonel’s eternal title and that story: Rank lives on when the facts are forgotten. In the family, Robert L. Montgomery remains “the Colonel” to this day. The title is like one of those stately gateposts, still standing after all other traces have disappeared.

So the Colonel withdrew from what he called “active business” at forty-two after the dissolution of the investment banking partnership. He turned to managing his investments, serving on boards, and pursuing miscellaneous personal interests. In anticipation of Prohibition, he laid on enough champagne, my father would later say, to last the family for decades. He became active in the campaign for Prohibition amendment repeal, set up the bar manager of his men’s club in the bootlegging business, and tried his hand at home distilling. He took up flying, having been warned off of foxhunting and steeplechasing for health reasons. He bought several airplanes and an autogiro. And, in one of the more curious stories I heard, he had mature oak trees shipped across the Atlantic after hearing they were to be felled on some distant Scottish relative’s estate. He stored them in a hay barn, where they sustained a colony of termites for a time before finally being hauled away.

The crash of the stock market put a dent in the Montgomerys’ wealth. But the extent of the damage is unclear, at least to me. In the 1930 census, the big house was valued at two million dollars. Later in the decade, I find the Colonel asking the township to slash the entire estate’s valuation to just four hundred thousand dollars. Turning down a tenant’s request for a rent reduction, he says the rental income from his properties is barely covering operations and upkeep. As for his investments, he tells a friend in 1933 that their market value is a fraction of what it once was—“but today they have kept up their income payments and I am no worse off.” The same year, he cuts his employees’ pay by 20 percent, blaming shrinking dividends and rising taxes. He tells a friend that his income has been “substantially reduced” and that he’s worried about an income tax hike. Yet he says the new brokerage, started with his son and son-in-law, has done “very well and, indeed, transacts one of the comparatively large volumes of such business on the New York Stock Exchange.” It has “neither made nor lost any great amount of money.”

The election of President Franklin D. Roosevelt finds the Colonel increasingly politically active. A local newspaper called him the township’s Republican boss. By 1933, he was heading a taxpayers’ league, bent on slowing the rise in the cost of county government. Meanwhile, legislation passed in Washington in response to the crash and the Depression put an end to a business practice that had helped make the Colonel rich—a practice my father called “kiting public utility companies.” The Public Utility Holding Company Act put a stop, in 1935, to the creation of huge utility holding companies. The Colonel, professing to champion the interests of small stockholders, railed against Roosevelt: “We ask for a square deal, not a New Deal.”

By the late thirties, the Colonel’s lawyer was telling township officials that the value of the Montgomery property was plummeting. Nearby estates were being unloaded onto the market, he said; even the foxhunters were leaving in search of open land to the west. In 1939, I find, the Colonel flew in from South Carolina in his private plane to testify against a neighbor’s plan to donate her estate to be used for a home for twenty “convalescent crippled children”—a move, at least partially philanthropic, that would have removed her thirty-six acres from the tax rolls. “Why, I could give my estate to Delaware County and save all these taxes, enough for me to live on my South Carolina plantation,” the county’s largest taxpayer thundered, in what sounds quite like a veiled threat. “The schools are piling on new things and additional buildings all the time, and taxes are always advancing. It is very difficult to maintain a large estate nowadays.”

Ardrossan wasn’t the only white elephant imprinted on the consciousness of my father. There was Chiltern, the four-hundred-fifty-lightbulb fortress on the Maine coast, to which he was dispatched during childhood summers to stay with his widowed Scott grandmother and various cousins, uncles, and aunts. Each of those houses loomed on the horizon of his emotional landscape, each with its family legend attached—the tale of the aspirational future Colonel, horseless on the hilltop, espying his future, and the story of the doomed railroad heir’s vow to build himself a gilded cloister if he couldn’t snare the woman he loved. Over the decades, my father observed his elders shoring up those monuments. If he ever entertained the possibility that the cause was lost, he must have concluded it was not. Otherwise, why would he embark, as he would do near the end of his life, on the grandest restoration campaign of them all?

By the 1930s, Bar Harbor had changed since the days when Edgar the elder had used his vision of luxurious rustication to entice Maisie Sturgis. With the advent of the income tax and World War I, “cottagers” had begun pulling up stakes. The arrival of automobiles on the island had brought a new class of tourist, and the stock market crash and the Depression made it harder to pay large staffs to operate dinosaurian summer homes. But my father’s grandmother Maisie Scott retained a romantic attachment to Chiltern. In 1929, she’d extricated herself from the king-size house that her husband had built in Lansdowne, Pennsylvania, and moved to a more manageable place on the Main Line, freeing herself to pour her money into perpetuating Chiltern. In the style of a benevolent despot, she presided over a rolling open house for four months every summer. In the first thirteen summers of my father’s life, his parents regularly packed him off to Chiltern. He and his cousins were often long-term guests. Years later, they’d remember those summers as idyllic.

My father rode the Bar Harbor Express up from Philadelphia, often unaccompanied by parents, and with or without his brother. He shared a bedroom with his cousin Mike Kennedy, in the children’s wing on the third floor. From a playroom window, they could gaze across the crescent-shaped cove to a small island, Bald Porcupine. In the early morning, grandchildren would visit their grandmother in the sitting room adjoining her second-floor bedroom. At sit-down lunches in the dining room, marrow bones came individually wrapped in linen napkins, ready to be mined for their marrow with a long-handled spoon. There were steamed clams on Sundays, consumed competitively by the bushel. At dinnertime, the children dined in the playroom. Downstairs, long dresses were de rigueur. During long July and August days, the cousins played in the rocky tidal pools at the water’s edge. They climbed mountains, chauffeured to the trailhead with their grandmother and her Irish setters. Charlie Chaplin movies played in the Bar Harbor theaters. The house library was stocked with Dickens and Sir Walter Scott. There was tea on the octagonal porch. There was a vegetable garden where, during the Depression, the less fortunate could help themselves. “It was total security,” Mike Kennedy told me. More than thirty years later, as a hostage in Iran for four hundred forty-four days, Mike dreamed of Chiltern.

A feature of those summers was the beguiling presence of the children’s uncle, Warwick, my grandfather’s younger brother, named for their father’s friend who’d died on the Sagamore circumnavigation. A born parodist and performer, Warwick had gravitated to theater in school. After studying Shelley at Oxford, he’d become a lawyer—a courtroom showman who relished the formality of the interplay with judges and other lawyers, and made a fetish of being correct. At six foot four, with gray-blue eyes, he was a memorable courthouse figure, attired in a long coat and in gloves that he removed theatrically, for maximum effect. He was a tennis player and a competitive sailor. When the United States entered World War I, he’d begged his parents, at age sixteen, to let him join the Coast Guard. Thwarted on the grounds of youth, he’d arranged instead to do his bit for the war effort by raising sheep on the Chiltern lawn. His nephews and nieces adored him—a childless uncle with a fanciful imagination and a sense of humor rooted in the ridiculous. On racing days, he’d climb to the second-floor balcony, brandishing a red megaphone and uniformed in a blazer and cap, and call across the water to the family’s boatman. By the time he and his crew had crossed the lawn, his racing boat, Artemis, would be waiting at a neighbor’s dock. He’d take along a small nephew as ballast.

In a photo, I find my father, at two, against a backdrop of billowing flower beds in the garden at Chiltern, in the company of his parents’ cook and maid. From a letter written the summer he turned nine, I find he’s requested his parents’ permission to stay an extra month—a request that, it seems, was promptly granted. His parents themselves spent little time at Chiltern: Edgar worked during summers; Helen Hope spent those months developing young horses for the fall. She had no interest in sailboat racing or tennis. In fact, she appears to have detested Chiltern. THRILLED TO BE COMING HOME, she cabled my grandfather from the train, after leaving my father, age two, and his brother, six, in Bar Harbor. COULD NOT STAND IT THERE. She didn’t entirely trust her darling at home alone, it’s evident from letters. Plus, relations with her mother-in-law were frosty. Maisie Scott disapproved of the fast life Helen Hope favored, and Helen Hope had no intention of knuckling under to her mother-in-law’s house rules. Once, I’m told, Maisie excavated a wayward corset buried beneath a sofa cushion; on another occasion, Helen Hope may or may not have been the prime suspect in the case of a newspaper that her mother-in-law found unfolded. The final blowup is said to have come one summer when Maisie tore into her daughter-in-law, newly arrived in Bar Harbor, for her deficiencies as a mother. The rupture was so deep, it’s said, that my father’s parents walked out. From then on, they returned only for occasional, awkward, duty visits.

As a boy, my father sensed that he was somehow sullied in the crossfire. Years later, he’d describe his grandmother as terrifying—a person who, he said, disapproved of him because he was “too Montgomery.” He suspected she preferred his brother, her firstborn grandchild and her late husband’s namesake. It seems she felt my father could have benefited from some parental attention. Ensconced in the Oak Room, she once observed an intimate moment between my father’s cousin Mike and his father, talking quietly on a window bench, the son nestled in the curve of the father’s arm. Turning to her elder daughter, Maisie said ruefully, “If only Bobby had that.”

In my father’s childhood letters to his parents, I’m struck by how hard he worked to please them. There had never been a better Christmas, a more wonderful vacation, more popular parents. “There are lots of people who keep mooning over the fact that ‘the most attractive people on the face of God’s earth aren’t here,’” he wrote from Maine at seventeen. “And since I found out long ago that it always means you, I thought you’d maybe like to hear it.” In his letters, he inquired after every aunt, uncle, grandparent, cook, maid, horse, and dog by name. He solicited his parents’ views on the Bretton Woods Conference and the presidential election, and gently ventured his own. “Please don’t think me fresh, or criticizing your opinions,” he wrote. “I don’t, but merely vehemently express my humble ones.” Toying with the possibility of taking up pipe smoking, he gave them veto power. Instinctively, he knew which stories would pique their interest: “The possibilities and actualities of my love-life are most glowing and very bewildering. I’ll tell you about it all someday.”

At boarding school, he was his own harshest critic. In report cards, teachers praised his “powers of imagination, and his lightness of touch, combined with his seriousness of purpose.” They remarked on his “keen interest in philosophical ideas and problems of man’s life.” Yet, writing to his parents, his self-criticism was savage—albeit in humorous, hyperbolic terms. His grades would be “putrid,” he predicted: “I know they’ll stink, or at least radiate a pungent odor.” They never did. He called himself “this x&*!#& lazy oaf of a stinking son of yours.” He castigated himself: “I have been so damned, damned, damned lazy all term, and am furious with myself. I am terribly sorry and will do better next half term.” Maybe he was managing their expectations, or his own. Or perhaps he was more attuned than others to the many ways he imagined he could fall short.

One relative whose affection he cannot have doubted was his mother’s artistic sister. As a child in their father’s horse-centric household, Mary Binney had taught herself to fall off so she’d be allowed to go back inside to resume doing the things she loved. When the Montgomerys had traveled as a family, she’d packed a portable encyclopedia. She’d studied piano at the Curtis Institute of Music, founded a dance company, worked as a choreographer, and taught dance. Because she was not yet married and longed for children when my father was young, he became, one of her daughters told me, “her first child.” She took him to the orchestra and the art museum. He spent afternoons at her dance studio after school. “She is having him again Saturday a.m., at his request, to watch her class,” his father reported to Helen Hope. “(Is this good for young lads?)” When Mary Binney, as a single woman, adopted the first of her two daughters in the early 1940s, she made my father, age twelve, a godfather. And when Mary Binney died at eighty-eight, my father confessed to her younger daughter that he, too, felt he’d lost the only person who’d always believed he was perfect.

In the fall of 1943, my father’s brother, Ed, left Groton after his junior year to join the Marines. Because he’d go from the Marines to Harvard to marriage, he was out of his parents’ house at seventeen. In his absence, Helen Hope turned her attention to my father. “Fate having taken one son away from her influence made her think, ‘That’s not going to happen again,’” Ed told me. “‘We’re going to make sure we see a lot of this son.’” She worked hard at becoming close to my father; she also groomed him for the glamorous circles to which she was drawn. “I think she would have been pleased to see him marry a countess,” Ed told me dryly. My father, surely, welcomed his mother’s renewed interest. (“When the light was shining on us, we were very much there. When it wasn’t, we made do.”) He was also endowed by nature, it seems, with the social skills she intended to impart. By the time he graduated from boarding school, he’d aced her tutorial. In his high school yearbook, the story chosen by the editors to illuminate his true self concerned a formal party he’d evidently hosted: An interloper, caught crashing the party, is chagrined to receive a personal invitation from the host to stay.

“The act was a revelation of the essential Scott,” the editors wrote, “since it involved humor, urbanity, appropriateness, and, above all, society.”

When I was a child, my father’s widowed Ardrossan grandmother, Muz, would disappear from Villanova every winter. Her destination was a plantation near Georgetown, South Carolina. I was too unworldly to question why this birdlike creature, descended from Puritan stock, made her annual migration to a rice plantation in the Deep South. My parents went rarely; even my grandparents made other plans. Only my grandmother’s youngest sister, Charlotte Ives, spent much time in that part of the country; she lived year-round near Georgetown, in a house not far from her mother’s. When Charlotte Ives came north to visit, she materialized in a lumbering black limousine, which rolled like a pirate clipper into the circular driveway in front of the big house, scattering yellow pebbles in its wake. From the limo would emerge a piebald Great Dane, the size of a small horse, its unnerving mouth foaming, and this perplexing auntie who, then in her fifties, appeared to be unable to walk. On the rare occasions when we asked why, my father would say she’d fallen off horses once too often while riding without a hat. Or he’d say she’d been bitten by a mosquito in the cypress swamps of South Carolina, and had come down with something he called cerebral malaria.

In my thirties, I found myself in South Carolina for the first time. The strongest and costliest hurricane in the state’s history had made landfall a few weeks earlier at a shrimping town south of Georgetown. I was a reporter in California, visiting a friend a few hours’ drive from Georgetown. On a whim, we decided to find out what had become of the Montgomerys’ plantation, which I knew had been sold, after the death of Muz, to an engineer who’d helped design the interstate highway system. On the outskirts of Georgetown, we found the entrance to the driveway—an unpaved road that ran for two miles through piney woods, strewn with fallen branches, before turning into what had once been a handsome avenue of live oaks. Tumbledown wooden cabins, some dating from before abolition, lined what was called, in that willfully nondescript plantation terminology, “the street.” The driveway came to a stop in front of an unprepossessing white plantation house. Its lawns were littered with branches and debris. The impression left was one of unimpeded decay.

An elderly African American couple emerged from one of the slave cabins. They’d worked on the plantation, they told me, in the Colonel’s time. They’d stayed on in the cabin after the plantation was sold, receiving a small pension from Helen Hope. Inside their house, aqua-colored walls were partially covered in fading snapshots. Peering at the round face of a pale-skinned, curly-haired woman on horseback in one of the pictures, I recognized Auntie Ives. The big house in Villanova loomed behind her. She was young—the wild child in the portrait in the ballroom, who’d ridden show jumpers for people with names like Guggenheim before whatever terrible thing that had happened to her had set in.

On the field trip that day was the man I’d marry a few years later. He had no reason for sentimentality about this moody, decrepit outpost with its murky connection to my father. He’d spent his life in Southern California, the shimmering land of insistent novelty, the starkest of contrasts to this Southern Gothic rot. Yet the abandoned rice fields, the mangled trees, the devoted couple seized his imagination. An irrational impulse—to rescue, to restore, to reclaim—washed over even him. Encountering my grandmother some months later, he announced gallantly that, if he ever had money, he’d buy back the plantation, rejuvenate it, and return it to her family—in whose possession he imagined, for whatever reason, it belonged.

A look of irritation crossed my grandmother’s face.

“That’s a terrible idea,” she snapped, with a sharpness that took me aback.

Then she added, in a line that lodged itself deep in some recess in my head, “People went down there and drank themselves to death.”

Georgetown, I now know, was once the heart of one of the most productive rice-growing regions of the world. Because of the surrounding area’s climate and terrain, and because of the exploitation of staggering numbers of enslaved people, South Carolina low-country landowners became, in the first half of the nineteenth century, among the richest people in the United States. After the Civil War, emancipation helped put an end to large-scale rice growing in the region. Abandoned rice fields became vacation homes for hundreds of thousands of overwintering birds. Land prices plunged, opening the door eventually to rich Northerners eager to spend some trivial fraction of their wealth on plantations for use as hunting retreats. In the early twentieth century, there were Vanderbilts, du Ponts, and Huntingtons spending the winter months on plantations in the Georgetown area, along with Bernard Baruch, the financier and an adviser to Woodrow Wilson, and Isaac Emerson, the inventor of Bromo-Seltzer. Visiting a friend near Georgetown in the second year of the Depression, Colonel Montgomery saw a seven-hundred-eighty-acre plantation, called Mansfield. He made a lowball offer. Confident that it would be rejected, he and Muz left for the West Indies—only to discover, upon returning home, that Mansfield was theirs. Muz is said to have had grave misgivings.

The street

The resuscitation of that neglected remnant of the age of slavery gave the Colonel a project—just as the extravagant resuscitation of the Colonel’s Edwardian estate to the north would give his grandson, my father, a project sixty years later. The Colonel converted the plantation house’s freestanding kitchen and its school building into two-story guesthouses. He built a third guesthouse from scratch. To the main house, he added a basement kitchen with an oyster bar where his houseguests could congregate before lunch to gorge on oysters and another local delicacy, the tiny crabs that lived in the oysters’ gills. He modernized the slave cabins, adding several more, to house his employees. He restored a historic rice-threshing mill. For navigating the rivers, lagoons, and bays, he bought a small fleet of motor cruisers. He installed a boathouse, dredged a canal to the Pee Dee River, and erected a glass pavilion as a picnic destination. Soon there were stables, kennels, an autogiro hangar, and an airstrip—used for, among other things, flying in lettuce from the greenhouse in Villanova. He tried his hand at growing rice—until it proved to be costing him twenty times what he would have paid to buy the same amount. After that, he flooded one of his rice fields, making a large, shallow lake, ideal for unsuspecting ducks. With a rich friend from the North, he’s said to have sent the owner of a Georgetown fish house to Russia for a crash course in caviar preparation—an approach the man then used to produce caviar from the Atlantic sturgeon that swam in the Great Pee Dee River and Winyah Bay. For years, homegrown caviar, packed in mason jars and shipped north by the case, arrived at houses on Ardrossan. My parents stored theirs beside the Popsicles in the freezer. Jars would be taken out and thawed for special occasions, when the caviar would be spread, like grape jelly, on toasted rectangles of Arnold Hearth Stone white, to be circulated on platters to guests.

The operation of Mansfield, like Ardrossan, depended on labor. There was a full-time foreman, a team of laborers, and a roster of local women who could be called up for duty in the kitchen and the houses at a moment’s notice. Maids, butlers, and the chauffeur from Villanova would make the trek south. The “inside tipping list,” used as a guide for guests, enumerated eleven hardworking souls. In the depths of the Depression, the arrival of a new employer near Georgetown didn’t go unnoticed. The purchase of Mansfield was front-page news in the Georgetown Times. Men, desperate for employment, wrote to the new owner, begging for work or financial assistance. (“Coming to the point instantly, I need a job,” one letter began.) Though the Colonel turned down requests from strangers for money, he did help employees by, for example, fending off a mortgage foreclosure or posting bail. But in the spring of 1933, having cut the wages of his Pennsylvania employees by 20 percent, he did the same at Mansfield. By the midthirties, some of his unskilled laborers were taking home just forty cents a day. In a letter to the president of the power company, the Colonel expressed a suspicion that the families in his cabins were squandering electricity. Each cabin had a four-lightbulb allotment. “If the darkies have been imposing on me, I will cut the power off and use it only in the hangar and laundry,” the irritated Northerner wrote. When his loyal foreman asked that the pay cuts be lifted in 1936, he received a dismissive response from the Colonel’s secretary. “He would be very sorry to have you go,” the secretary wrote, “but it is altogether all right if you want to.”

The foreman, I assume, knew nothing of the Colonel’s haberdashery budget. It appears from the evidence that, though the stock market crash and the Depression may have dented the Colonel’s wealth, they had not yet cramped his personal style. In a cardboard box in the ironing room, I found a heap of receipts dating from a mid-Depression shopping spree in London. Why the records were kept, I cannot know. Did someone anticipate that they’d be of interest? More likely, no one saw a reason to throw them out. As a result, I now know that on July 4, 1936, the Colonel and Muz settled in at Claridge’s, the London hotel, which was doing double duty as a refuge for European royalty in Mayfair. At least one purpose of the trip, it seems, was to replenish the squire’s wardrobe and inventory of hunting paraphernalia. Over a ten-day period, his purchases included, but weren’t limited to, five double-breasted suits, four pairs of jodhpurs, three riding coats, a dozen neckties, nine bow ties, a dinner coat, a “smoking suit,” patent leather pumps, seven foulard stocks (whatever those are), a pair of string gloves, three hats (deerstalker, Shetland fishing, Donegal), a silk muffler, suspenders, twelve pairs of silk and lambs’ wool socks, and thirty-three shirts. Also acquired in the same ten-day period: a pair of Chippendale mirrors, a Chippendale settee, a pair of mahogany chairs, one hundred twenty-five yards of chintz, two cases of thirty-year-old brandy, one hundred clay birds, four monogrammed pigskin cartridge bags, and a twelve-bore shotgun.

How to square the four-lightbulb allotment with one hundred twenty-five yards of chintz?

The Colonel was not entirely satisfied with his purchases. He complained to his shirtmaker, Edouard & Butler, that he’d been overcharged. The store’s managing director, with a mannered solicitousness barely disguising his disdain, called the colonial’s bluff. “We are very sorry to learn that such a longstanding and valued customer should be in any way dissatisfied with our prices,” he wrote, “but would point out that the materials we supply are the best it is possible to procure, as also are our cut and workmanship. If however you should acquire cheaper materials we could of course obtain them, but naturally in our class of business it is our policy to supply only the best unless specifically asked to the contrary.”

The Colonel, it seems, didn’t take up the offer.

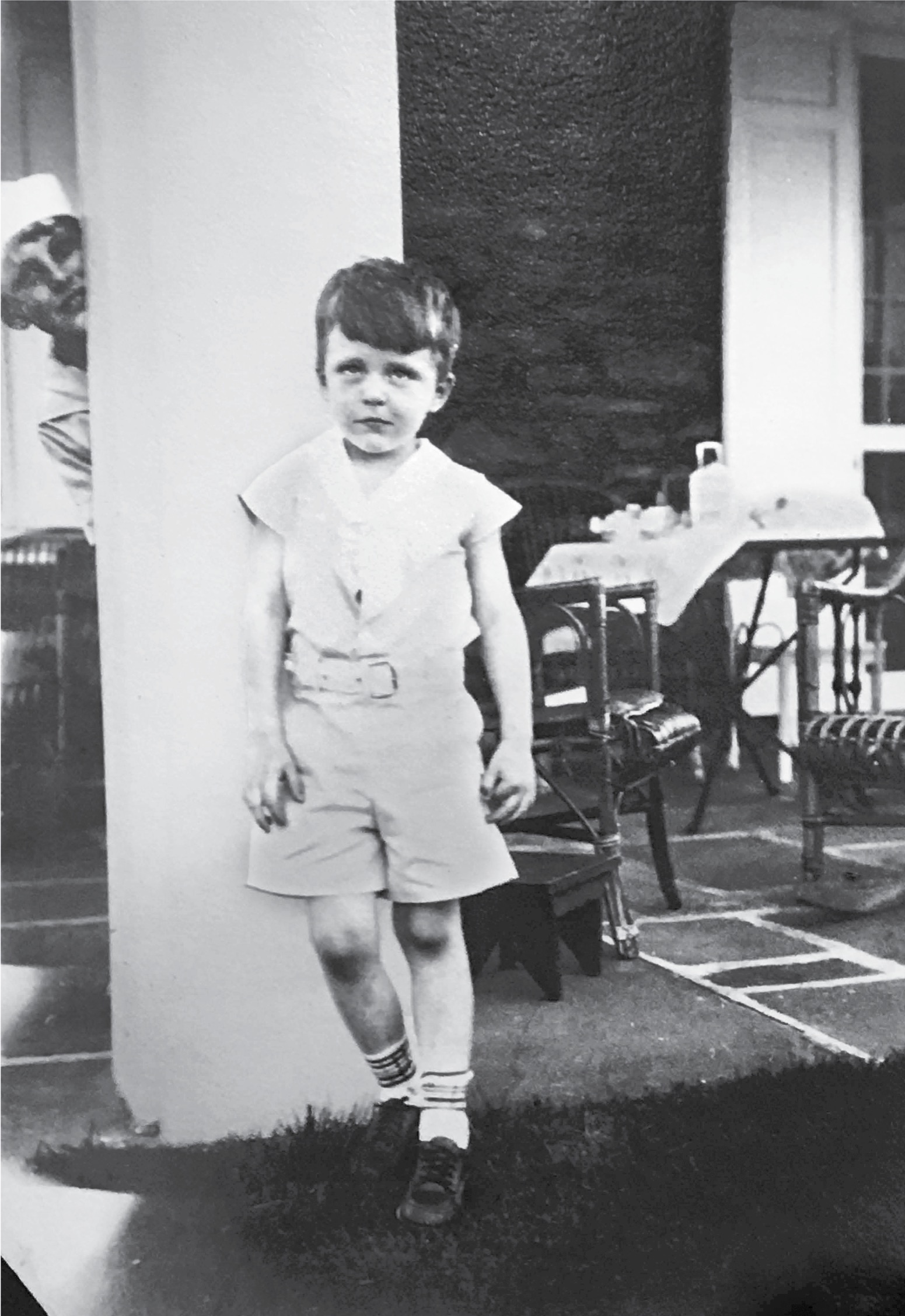

Life on the plantation was quiet in the extreme. My father’s brother, Ed, who was packed off by his parents to Mansfield for three months while recovering from bronchitis at age nine, remembered it as “very comfortable, very beautiful, really dull.” He recalled having seen not one child of his age during his recuperation—though once, after the call went out for roast pork for dinner, he saw a decapitated pig running in circles. In an album, I find a photo of my father, by himself at about the same age, balancing on a joggling board under a canopy of Spanish moss. From Mansfield, his mother had written to his father, several years earlier, “Really this place bores me stiff.” The antidote was houseguests. Acquaintances traveling by motor yacht were invited to dinner; friends and relatives arrived from the North by overnight train or made the two-day trip by car. On a set of typed driving directions, I happen upon this admonition: “Do not ask Negroes for directions. Always ask White People, preferably a woman.”

There were boat trips, picnics, duck hunting, socializing with neighbors. Charlotte Ives, the youngest Montgomery, whose taste in potential husbands cannot have escaped her father’s judgment, finally eloped, at thirty, with an unsuitable South Carolinian about whom all details have been erased, except that he may have been a stable hand.

How long were they married? I asked my uncle.

A week? he ventured.

“I was told it happened,” he said. “Everybody was aghast. And then it un-happened.”

In the Georgetown County Judicial Center, a clerk directs me to a rack of red leather-bound volumes listing marriage licenses by year. In a volume labeled “White,” I find a listing for the marriage of Charlotte Ives Montgomery and Edward Mitchell. No one seems to remember, or be willing to say, why the union soured. Whatever happened, and it cannot have been good, the bride’s mother came hastily to her daughter’s rescue. In the big house, I find a flurry of letters between lawyers for the family in the immediate aftermath of the elopement, full of cryptic references to “the unexpected marriage” and the need to put certain property in trust. There’s later correspondence, too, referring to a car accident and the near impossibility of insuring Charlotte Ives in the event of an accident such as a fall downstairs. There are vague allusions to “her present condition” and the “undesirable risk” she presents for insurers. Her mother reports that Ives “hobbles a bit further” each day but that “it is very painful and aches most of the time.” She is happy with her animals and her house, her mother writes, but “if she lost those there would be very little in life for her.” Later, in her mother’s letters, there are mentions of difficulties with balance, and a reference to her being on the wagon.

Food and drink occupied much of the day at Mansfield. For houseguests, there was the option of an early breakfast before being paddled out onto the lake for duck hunting at dawn. A full breakfast, including eggs and grits, awaited them upon return. Midday: oysters, cocktails, lunch. An afternoon nap, tea, more cocktails, dinner, bed. In the Colonel’s papers, I find he’s kept his orders for bourbon, cognac, Jamaica rum. “You know my weakness,” he writes to a friend in Georgetown. “. . . There is nothing more delightful than Johnnie Walker Black Label.”

The lifestyle took a toll on the host’s health. The Colonel, who’d given up foxhunting after a heart attack possibly precipitated by his having ridden two point-to-point races in one day, slid into an increasingly sedentary state. He ate, drank, gained weight. In the winter of 1935, a Georgetown doctor, alarmed by the Colonel’s blood pressure, ordered him to bed. The patient resisted, insisting the condition was a passing result of excessive entertaining and drinking—a problem he’d be unable to address until he got home. Back in Pennsylvania, he went to bed for a week in his second-floor bedroom, uninterrupted by social obligations. His blood pressure dropped to close to normal. The Georgetown doctor was informed of the good news. With what seems like a surplus of deference, the medical professional wrote back to his wealthy patient, “I can see my mistake in trying to rest you at Mansfield. It is impossible, and I think the few days you tried it made you worse instead of helping you.”

At the “cottage” in Maine, a shadow fell over the summer of 1941. War was raging in Europe and Asia. The United States would soon join. My father’s uncle Warwick had joined the Naval Reserve and was now a naval intelligence officer in the Pacific, deputy to the director of the port at Manila. Maisie Scott, the Scott family matriarch, was unwell. On the advice of a doctor, she departed from Chiltern in midseason, leaving her eldest daughter in tears. Back in Pennsylvania, a surgeon found, in Maisie’s intestines, a cancer so advanced, he simply took note of it, then stitched her back up. “Don’t bring me back to any half-life,” she’d instructed him in advance. When she died that fall, at sixty-nine, the town of Bar Harbor shut down for the afternoon of the funeral. The selectmen turned out to pay their respects. My grandfather and his sisters carried their mother’s ashes to the top of Newport Mountain, then scattered them on the rocky slopes where she’d hiked, her voice slicing the still air as she called to her dogs.

Manila fell to the Japanese that winter. With the rest of the naval forces, Warwick retreated to Corregidor, the largest of the fortified islands protecting Manila Bay. American and Filipino soldiers held out there for four months against Japanese bombing and shelling. “I note one thing,” Warwick wrote to his family, two months in. “—that I love you all very much. Don’t ever forget that! I note another thing—that this existence being unguessable from day to day and not free from danger, does not inspire me to write you great things about life and death or to memorialize myself in some poetic effort about self giving his all in distant Asiatic sea or shore or wherever it is I am.” On May 6, 1942, the commander of Allied forces in the Philippines, Lt. Gen. Jonathan M. Wainwright, surrendered. “There is a limit to human endurance, and that point has long been passed,” he radioed to President Roosevelt. Taken prisoner along with seven thousand other Americans, Warwick was listed as missing in action.

Human endurance was to be tested further.

For nearly a year, the family received no word of Warwick. My grandfather, courteous by temperament and training, tapped his connections in the military, politics, and the press in pursuit of news of his brother. (“Dear Cabot,” he writes to Senator Henry Cabot Lodge Jr.) At one point, he was told that Warwick was a prisoner in a camp in Japan—“the model Japanese prison camp,” someone assured him. But letters to that camp were returned. Later, word came that Warwick was in a camp in the Philippines. A series of small, regulation-style, fill-in-the-blank postcards from him trickled in, bearing the minimal news permitted. Then communication ceased again, in late 1944, as the Allied campaign to take back the Philippines, the bloodiest campaign in the Pacific War, commenced. As the Allies retook the country, news of liberated prisoners trickled home; family friends hovered near their radios, in shifts, recording names. “They have, as I expected, no news on Warwick and no suggestions how to get any,” my grandfather wrote after visiting the offices of the Committee on Relief for Americans in the Philippines. “But they . . . say we can have good confidence Warwick is alive if we have not been officially notified of the contrary.”

One month earlier, however, with Manila under American aerial bombardment, the Japanese had herded some sixteen hundred American and Allied prisoners onto a transport ship headed to Japan. Nearly all the prisoners were survivors of the defense of Corregidor, Bataan, and Mindanao; many were emaciated and weak. At bayonet’s point, they were crammed into the airless hold. The ship, its decks studded with anti-aircraft guns, left Manila on the night of December 13, 1944. With no markings to indicate that it carried prisoners, it came under heavy fire from United States Navy planes. For a day and a half, the United States strafed and bombed it. Amid detonations and the groans of the dying, the blood of the Japanese gun crews ran in rivulets from the decks into the hold. In the blackness, men slid into madness. Crouched naked in temperatures estimated to have risen as high as one hundred thirty degrees, dozens are believed to have suffocated. On December 15, the ship burned to the waterline and began to sink in Subic Bay. More than three hundred of the sixteen hundred prisoners died. Warwick Scott, at forty-three, is thought either to have died from lack of oxygen or to have been killed when an American bomb hit the ship’s stern directly above where he huddled. His body has never been recovered.

In the months after my father turned sixteen, his father and his aunts pieced together, from the recollections of survivors, an account of the final months of their brother’s life. “If Warwick knew, as he must have, that the situation was hopeless, he never permitted his knowledge to affect his good cheer, consideration for others, and enthusiasm,” a fellow officer wrote. During the long siege of Corregidor, Warwick had built, equipped, and staffed three machine gun outposts, then directed anti-aircraft fire against the Japanese, for which he would posthumously be awarded the Bronze Star. In the prison camps, he was said to have cut an unforgettable figure—gaunt but dignified, in epaulets till the end. He’d taught lessons in conversational French; he’d delivered a lecture on French wines. With a concealed radio assembled from stolen parts, he’d gathered news of the outside world, reporting his findings to fellow prisoners in a news conference at night. There’s a story that he staged a production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream; a nephew remembers hearing that Warwick had written home for clarification on some fine point in act two. I found no mention of such a production in survivors’ letters, though perhaps it had been mounted in the months before the fall of Manila.

In Warwick’s absence, the house in Maine languished. With their mother dead and their brother at war, my grandfather and his sisters had neither the heart nor the money to carry on opening Chiltern each summer. As years came and went, it sat uninhabited, its garden gone to seed. Only the black-eyed Susans and other perennials persisted. Other families put their “cottages” on the market and migrated to smaller houses in other towns, where men could arrive for the summer without having packed a tuxedo. “Bar Harbor is finished,” my grandfather had declared. But he and his sisters resolved to do nothing about the fate of Chiltern until after Warwick’s return. Maybe he’d dreamed of the house while he was away, they thought; maybe he’d want to recuperate there. In which case, they’d open the house one last time. They’d give their brother, back from hell, one final, heavenly summer.

In June 1945, word came that Warwick was believed dead. My grandfather forwarded the Navy’s letter to relatives and friends. “Here is some sad news about Warwick,” he wrote in a brief note, poignant in its restraint. “A miracle could still happen and he might come back to us, but there is nothing to do but accept the report of the Bureau of Naval Personnel. We are very proud of him.” My father, at sixteen, spent part of that summer with his aunt and cousins in Maine, helping dismantle the house that his grandfather had built and that his widowed grandmother had dedicated herself to keeping. For weeks, my father assisted in the dusting of books, the sorting of furniture, and the deciding of who would take what. His father had waived any claim to the house, turning over his share to his sisters.

For himself, my father laid claim to his grandfather’s favorite Morris chair, and to a French antique desk made of mahogany that gleamed like a horse chestnut fresh off the branch. The desk had a galleried marble top and a pullout writing surface inset with leather. For years it stood in a corner of my parents’ library. My father’s paperwork drifted there in tidy heaps. The desk, with a bowed lid that opened to reveal its fitted interior, had certain advantages. If you tugged the lid from its raised position, it would rumble down a curving track and snap shut, like a garage door, hiding behind its handsome, polished exterior whatever confusion lay unattended inside.

The family emptied the summer palace and put it up for sale. But demand for mansions in those years was not robust. The real estate market in Bar Harbor was awash in oversized “cottages” that their owners were itching to unload. Forty-five years after that first summer at Chiltern, half the family was dead, and the survivors were left to tear down their father’s dream. A team of laborers embarked upon an exhausting process of demolition. My father’s brother, Ed, on a boat out of Bar Harbor that summer, vowed he wouldn’t look in the direction of Chiltern, according to a story one of his cousins remembers Ed telling. But Ed couldn’t resist. Turning, he glimpsed the lawn sloping down toward the crescent-shaped beach. He saw the house being dismantled. For years afterward, he’d say, he regretted that final look. Not long after, the family transferred the land to a corporation, which later declared bankruptcy and eventually was able to sell the property, in pieces, and cover unpaid back taxes.

In October 1947, smoke was spotted rising near a cranberry bog on Mount Desert Island. A protracted drought had left conditions on the island the driest on record. The fire smoldered for days before the wind picked up and changed direction, herding flames toward Bar Harbor. The blaze, becoming an inferno propelled by what were said to have been gale-force winds, traversed six miles in three hours. Reaching the town, it barreled down West Street, known then as Millionaires’ Row. By the time the conflagration was over, sixty-seven summer estates had burned, along with one hundred seventy year-round homes. For some, the disaster was a blessing in disguise: Many of the burned cottages, unoccupied for years, had been scheduled for demolition. “Even those who suffered extreme losses now admit that Bar Harbor cottage life was on the way out long before the fire, and that the fire was merely the coup de grace,” Cleveland Amory wrote later. My grandfather had seen it coming. Bar Harbor—that is, his father’s Bar Harbor—was finished.

Nearly sixty years later, I made an impromptu detour to the town. After five days in a cabin in the woods at the farthest reach of the Maine coast, I was driving south with my beloved when he suggested we see if we could find any trace of the house that my great-grandparents had built and their offspring had razed. Googling the name of the house some months earlier, I’d noticed the existence of a bed-and-breakfast in Bar Harbor with Chiltern in its name. Guests were shelling out upwards of two hundred dollars a night to stay in an inn said to have been “lovingly designed from the carriage house of an ambassador’s estate.” When we pulled into downtown Bar Harbor on a weekday morning in mid-September, flocks of senior citizens, in fall-colored fleece finery, were emerging from tour buses, flooding sidewalks, and spilling into streets. A short distance from the center of town, we parked in front of a two-and-a-half-story, gray-shingled building. One of the owners obligingly showed us around the inn. He even produced what he said were the original blueprints: twelve stalls, a carriage room, a harness room, a cleaning room, a toolroom, lockers, hay and straw chutes, and two car-wash-like “wash stands” for cleaning horses and carriages. The bed-and-breakfast had a sauna, a theater, and an indoor lap pool. In a guest bedroom, towels had been folded, origami-style, into swans, paddling on the surface of the king-size bed.

The owner pointed us up the street to the place where the putative ambassador’s residence had once stood. Where there had once been a single house, we found four. Three generations of the family that had bought the land in the 1950s now had summer houses there. The original garden, greenhouses, and tennis court were gone. Trees had recolonized much of the clearing. A landscaping crew was hacking at brush that was blocking access to the crescent-shaped beach. One of the only clues to who or what had once occupied the property was a rusting street sign at the entrance to a narrow cul-de-sac, called Scotts Lane. The other lay largely buried, obscured by grass and dirt, at the foot of a house on the site of the original. If you ran the toe of your shoe back and forth, you could expose a sliver of one of those enormous, squared blocks of granite, cut from a local quarry and put in place by thirty masons, which had inspired an awestruck reporter, back when, to liken Chiltern to “a modern fort”—indestructible and destined to last far into an unimagined but no doubt glorious future.