Two

1946–1959

POST–WORLD WAR II PROSPERITY

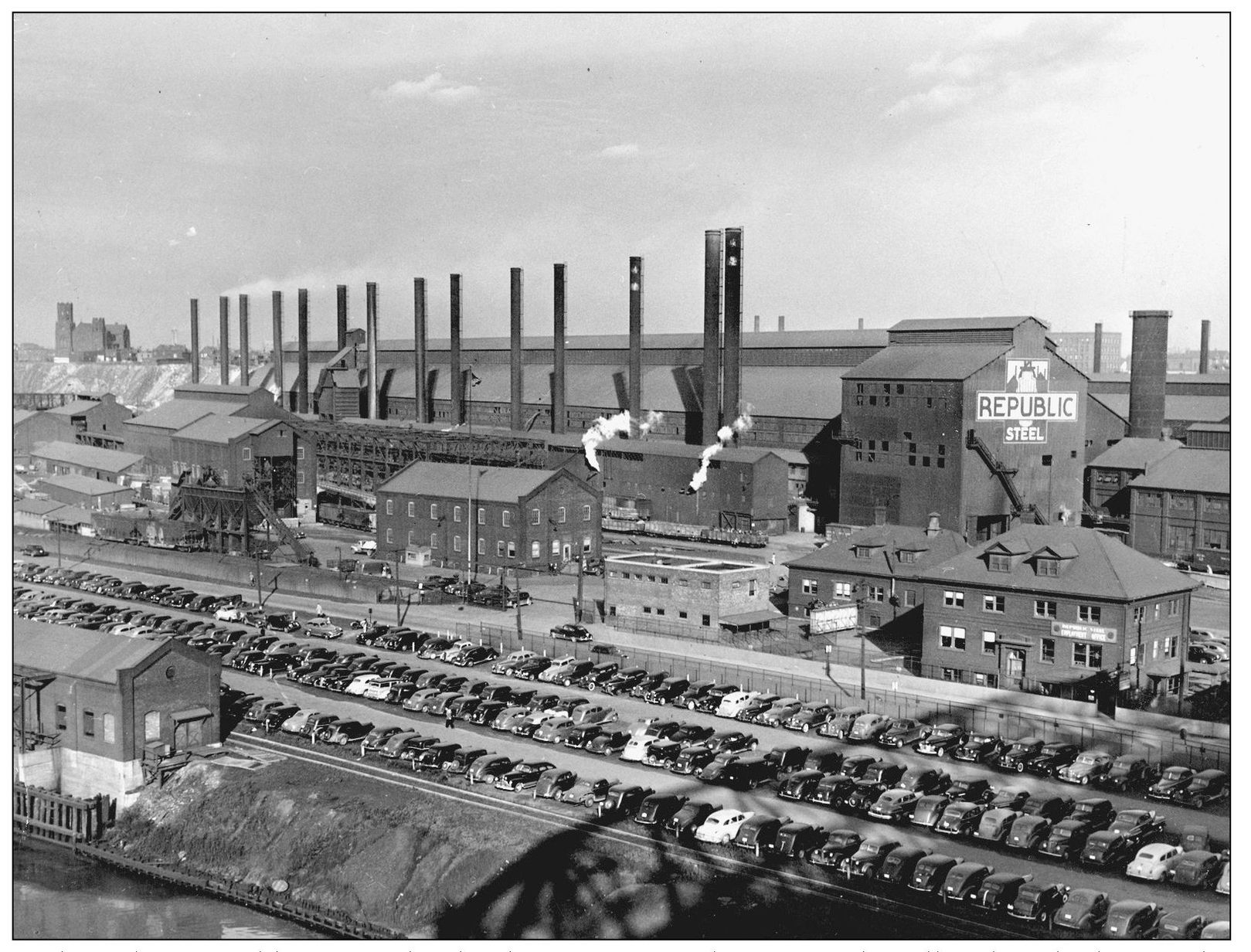

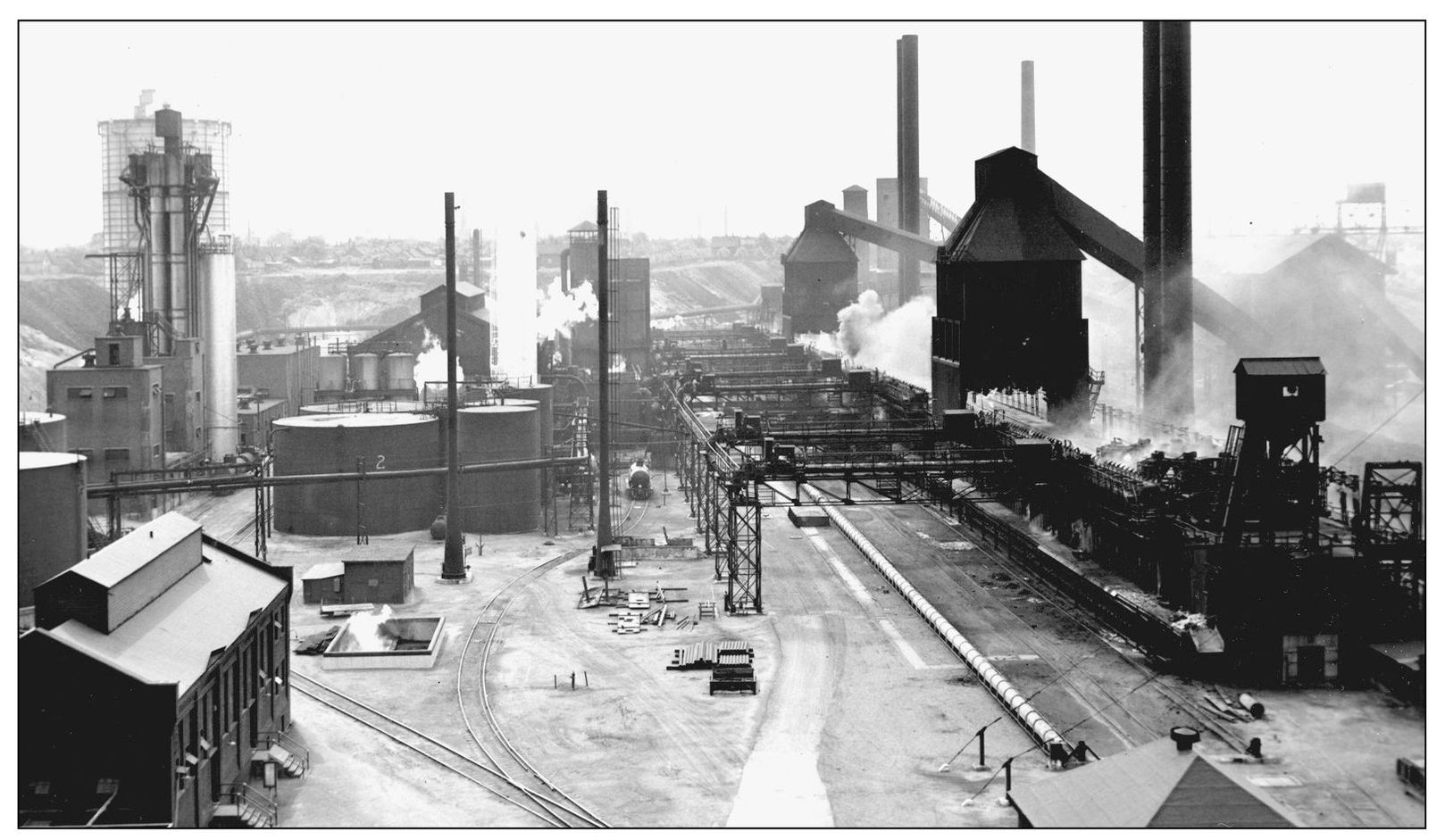

In the wake of World War II, Cleveland’s economy was booming. The full parking lot here at the Corrigan-McKinney works of Republic Steel gives an indication of just how many people enjoyed good-paying industrial jobs. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

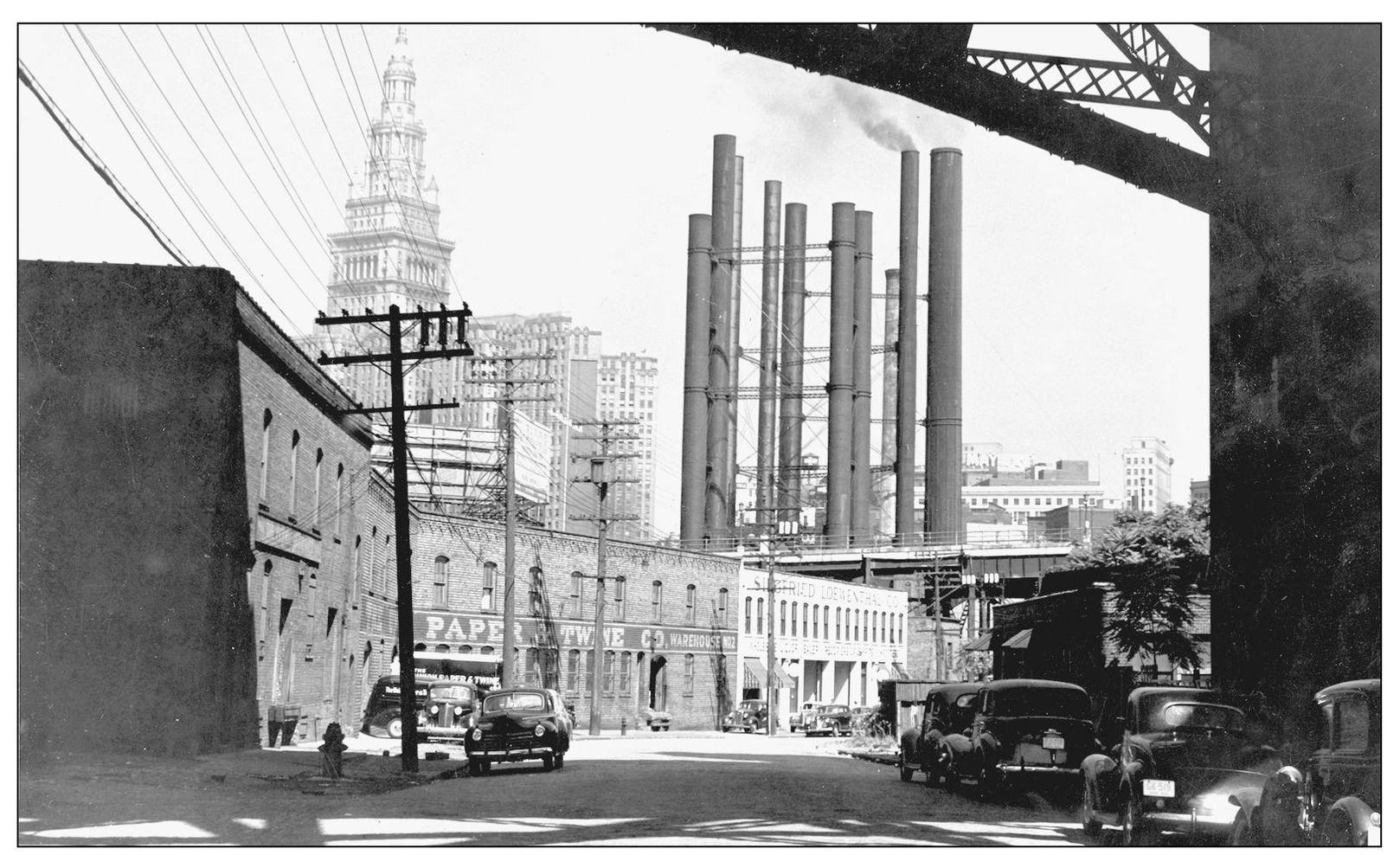

In the summer of 1946 this imaged was captured from beneath the Lorain-Carnegie Bridge, looking towards the north. Girders, stacks, and bricks often come together to form vistas such as this in the Flats. This image is also representative of the eclectic mix of businesses found in the region—a person would be hard pressed to find a paper and twine works located next door to a liquor wholesaler anywhere else in the city. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

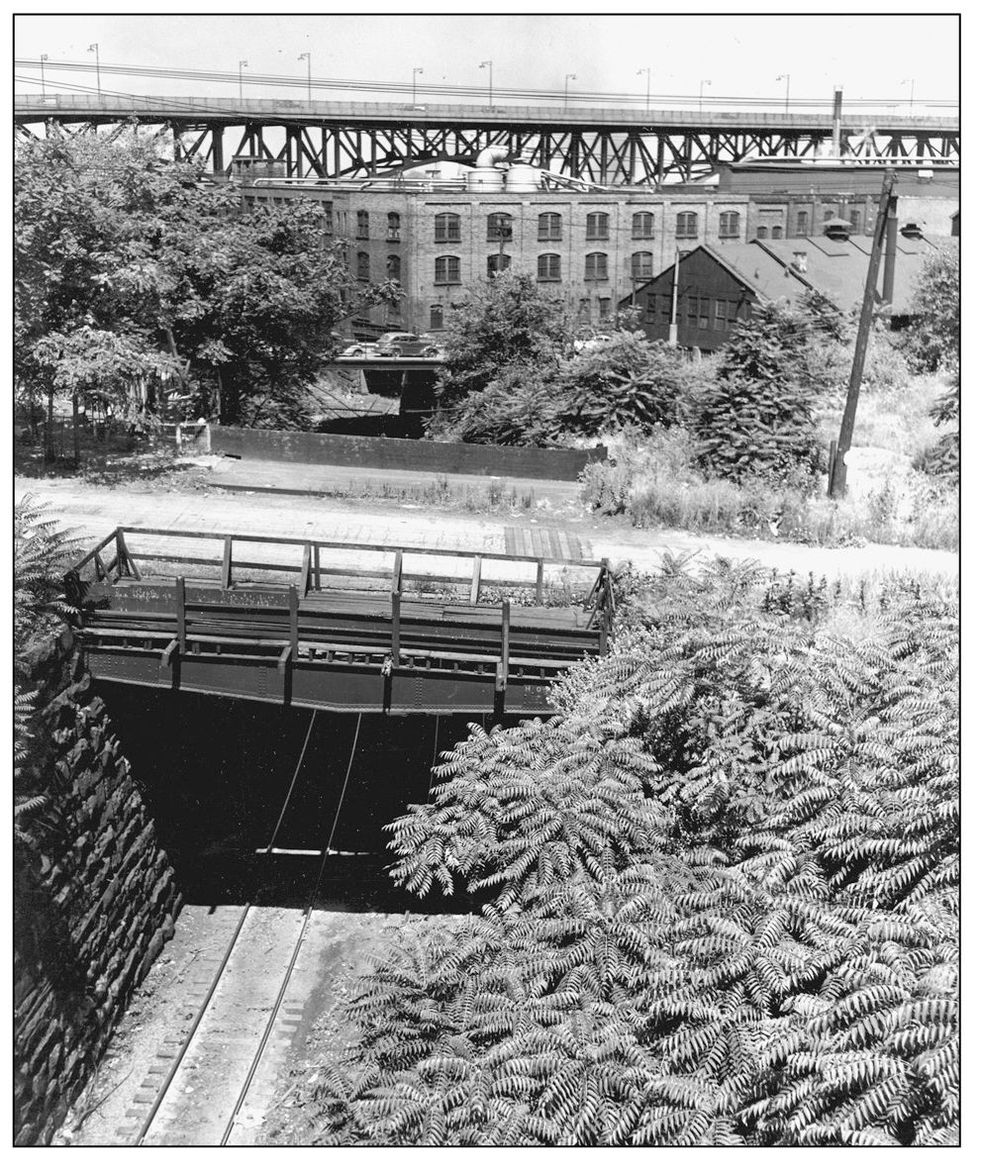

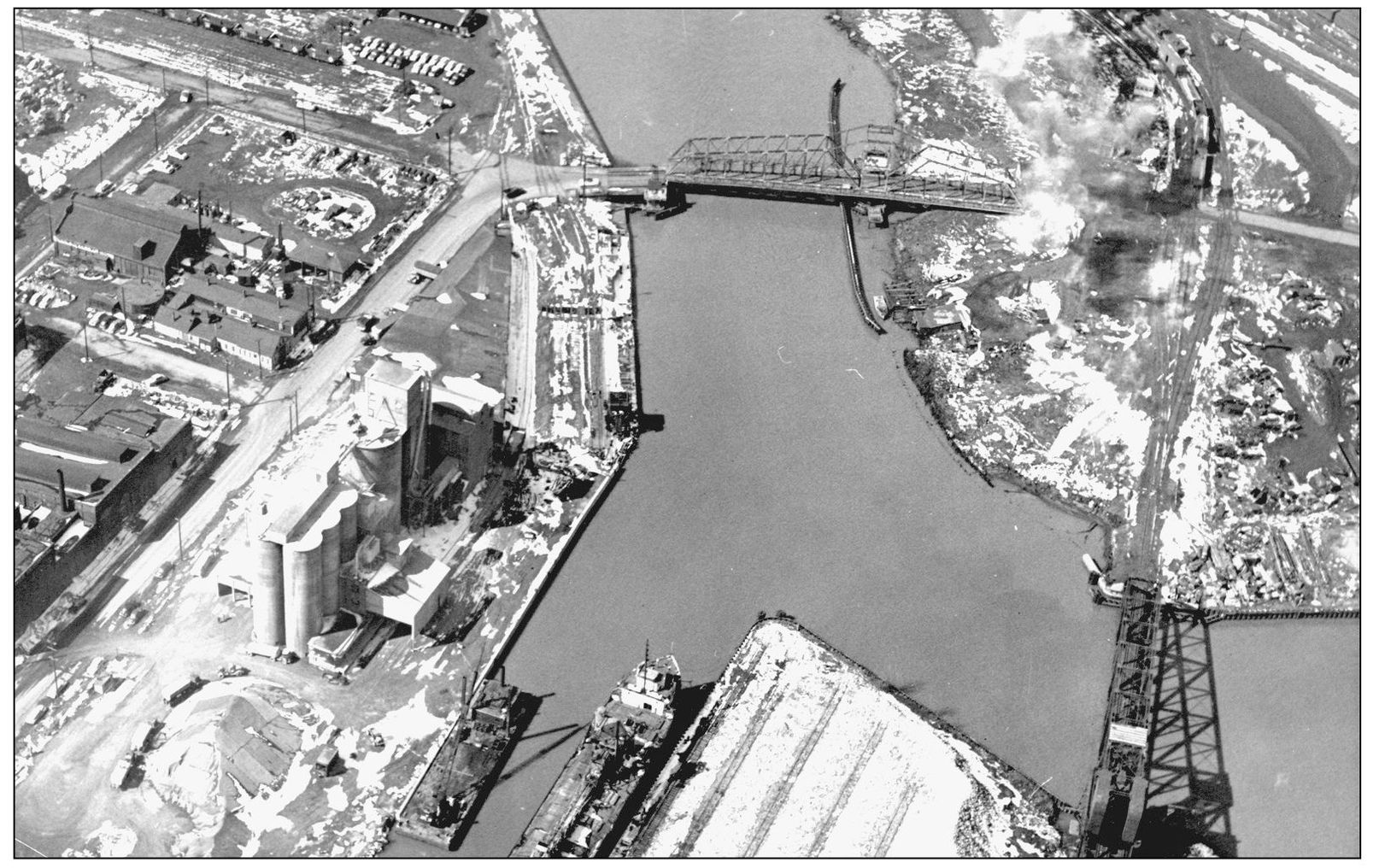

Although most of the Flats region is a landscape of man-made structures, mother nature does creep in from time to time. Often it is an attempt to reclaim her territory as in this view looking toward the Main Avenue Bridge. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

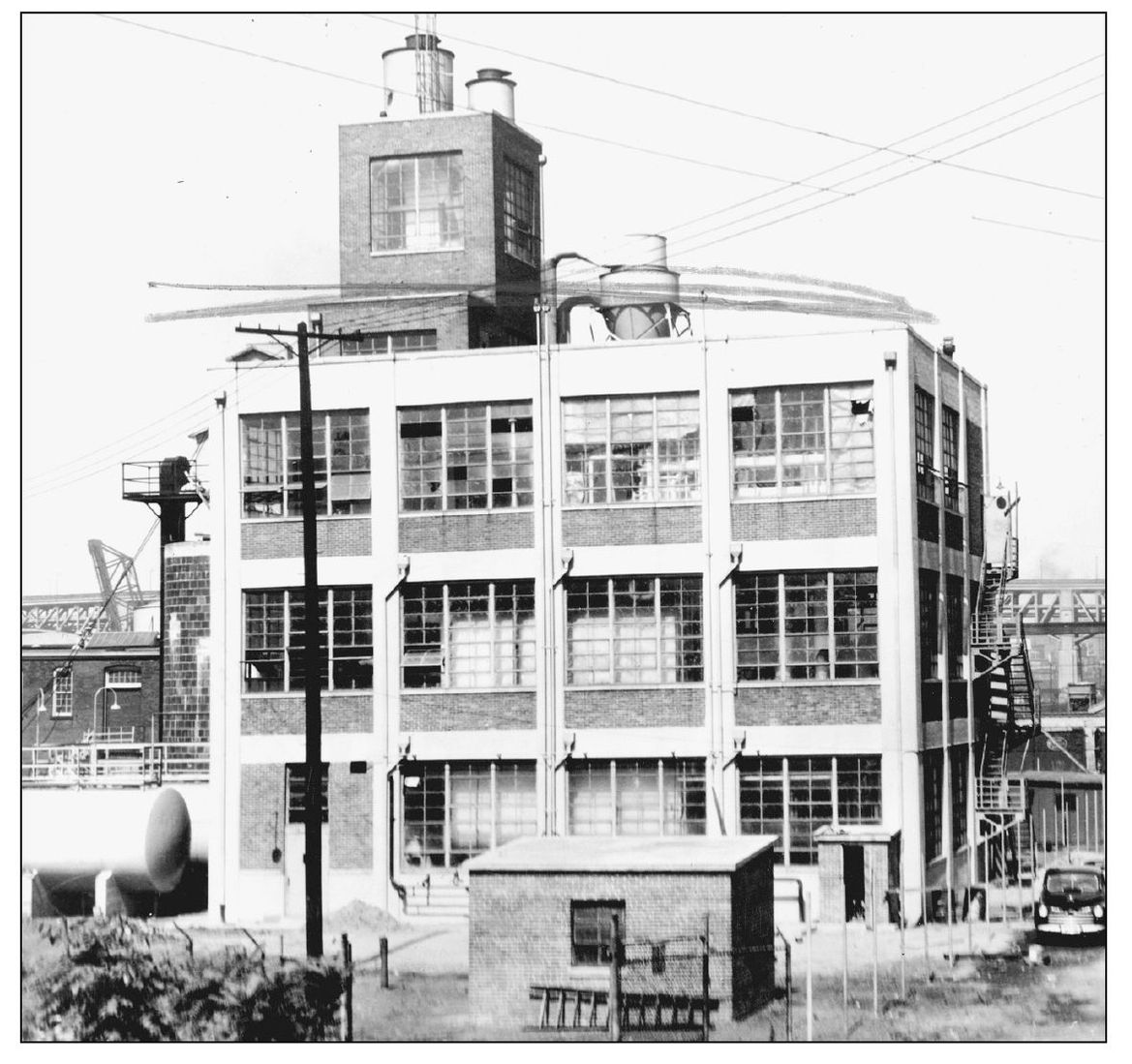

Sherwin-Williams, like Republic Steel, would be quite prosperous in the years immediately after World War II. This solvent extraction plant was built in 1947 at a cost of $750,000. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

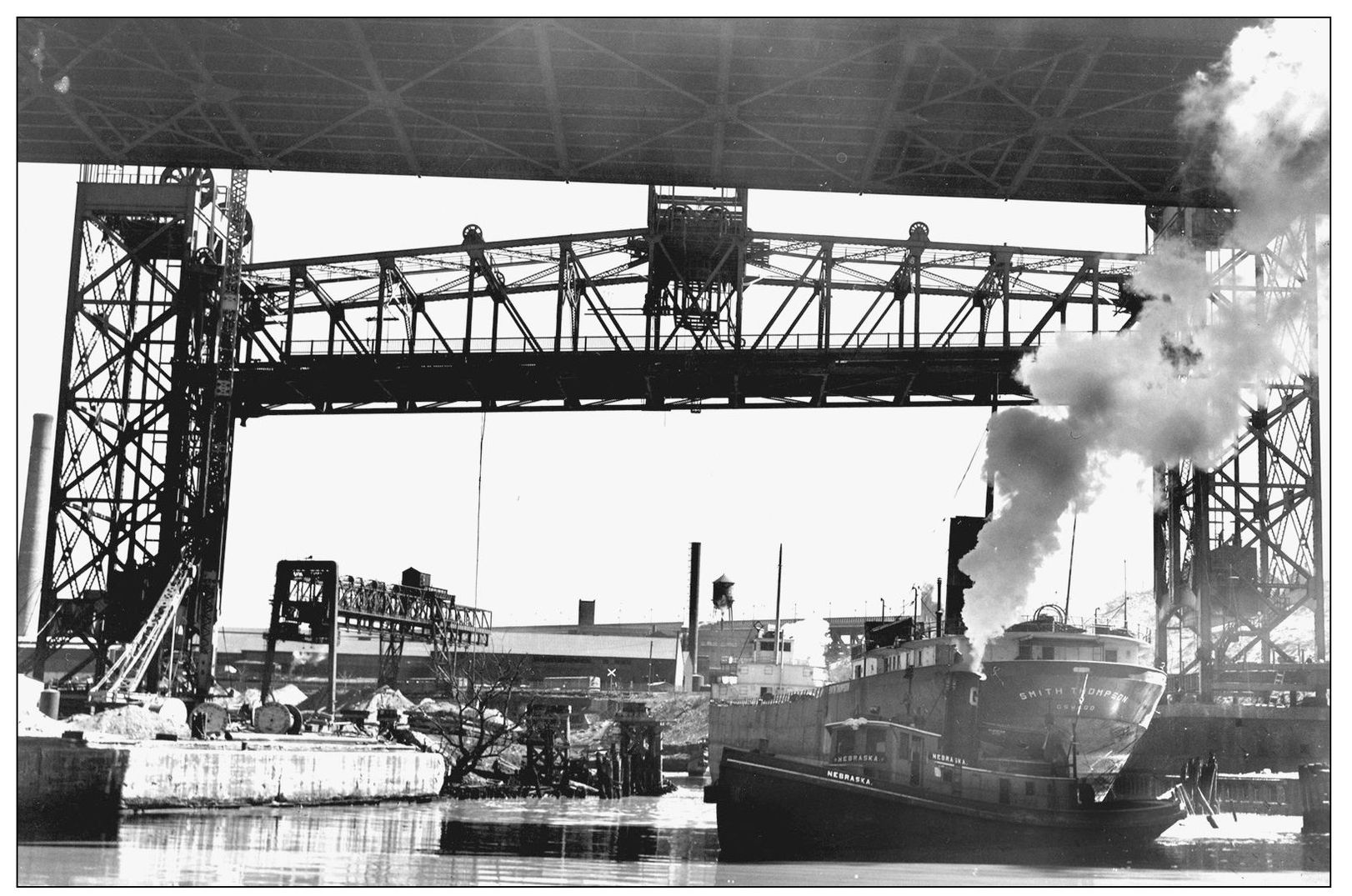

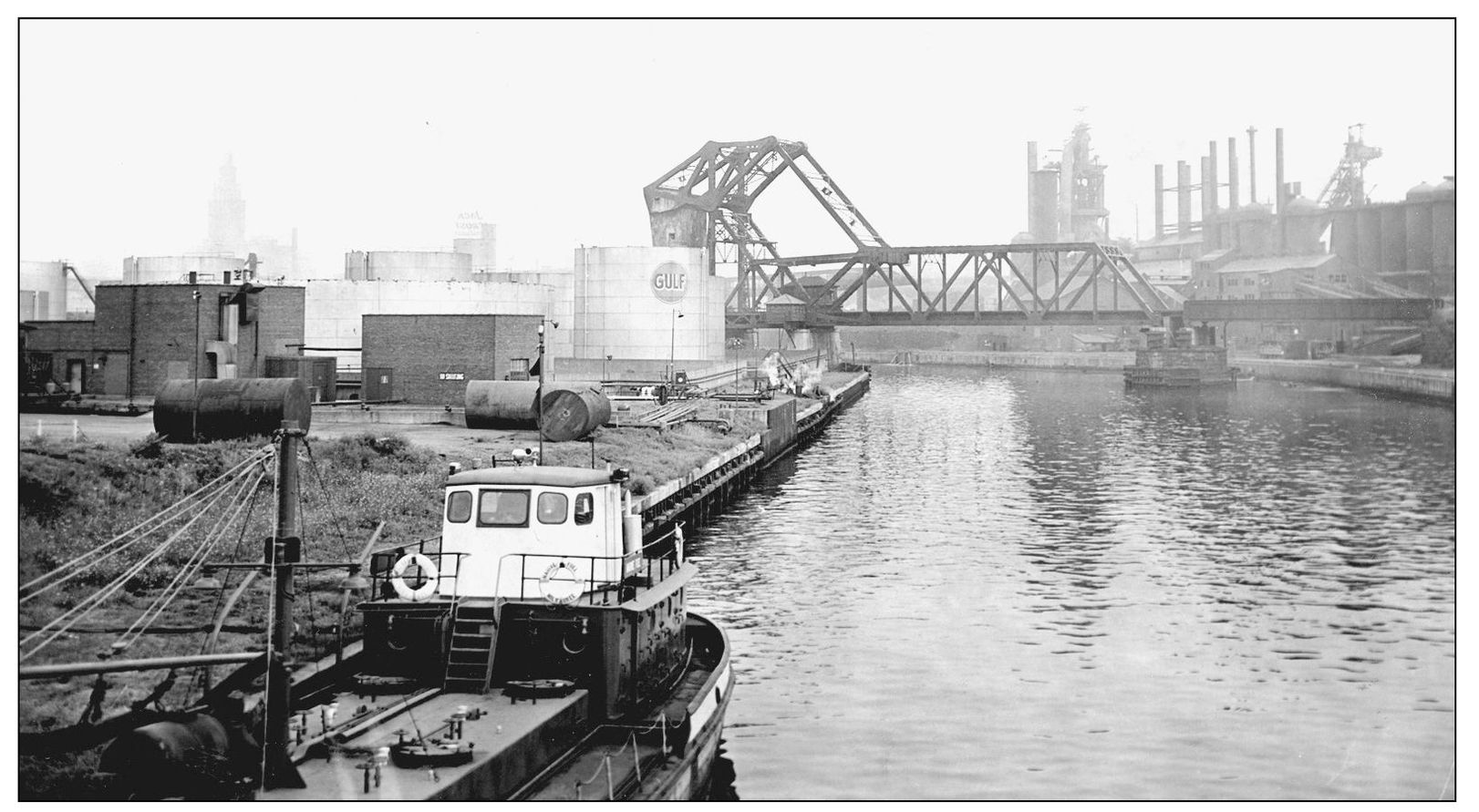

The tug Nebraska steams past the Smith Thompson near Cleveland’s steel mills in March 1948. The Smtih Thompson was built in 1907 and is seen here working for the Great Lakes Steamship Company. Like many steamboats of its size and age, the Smith Thompson was towed to Europe for scrapping in the early 1960s. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

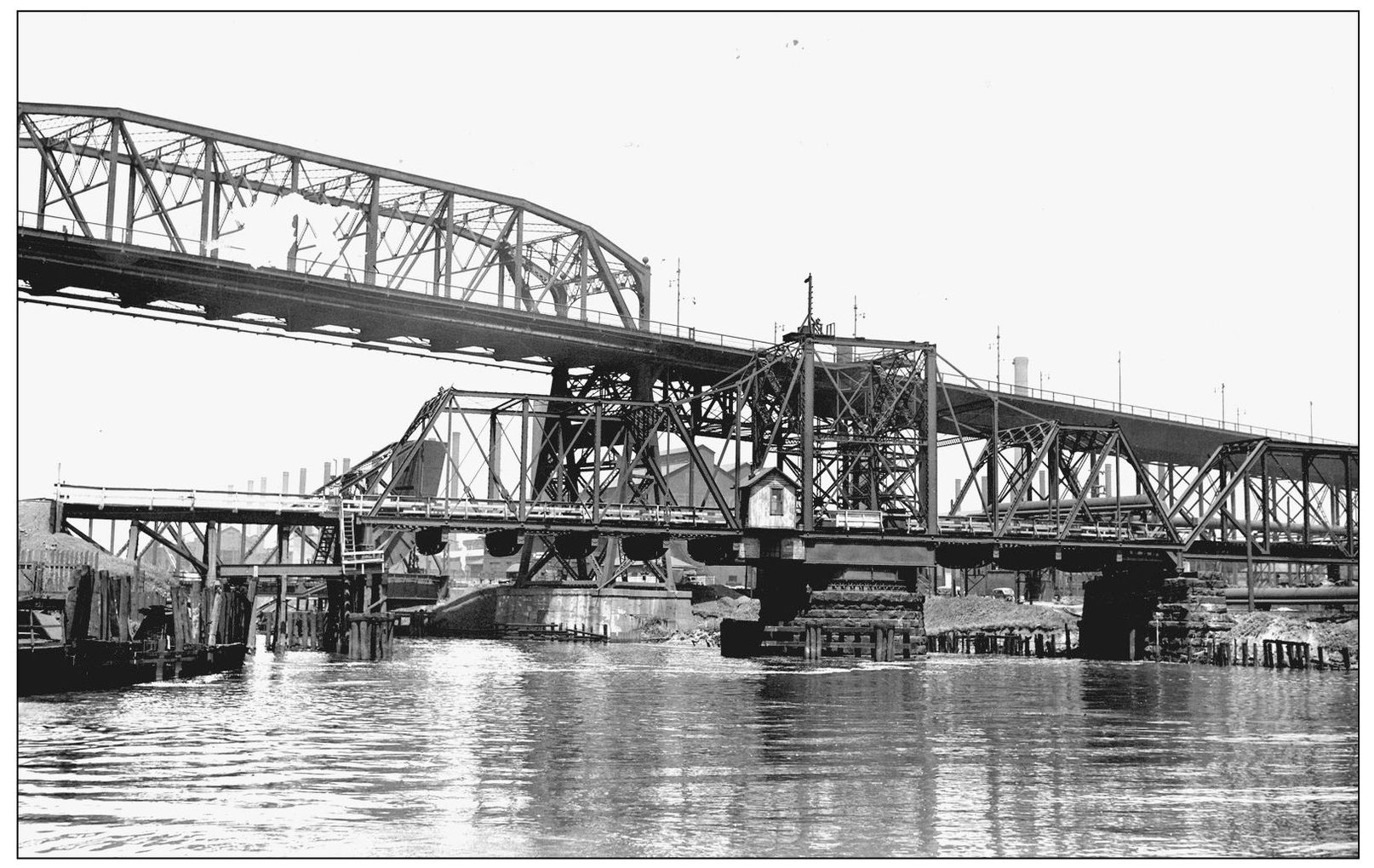

Three different varieties of bridges can be found in this image. The Wheeling and Lake Erie Railroad swing bridge comes first, followed by the Clark Avenue Bridge. Just on the other side of Clark Avenue is the River Terminal Railway Bridge, which connected Republic Steel’s operations on both sides of the Cuyahoga. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

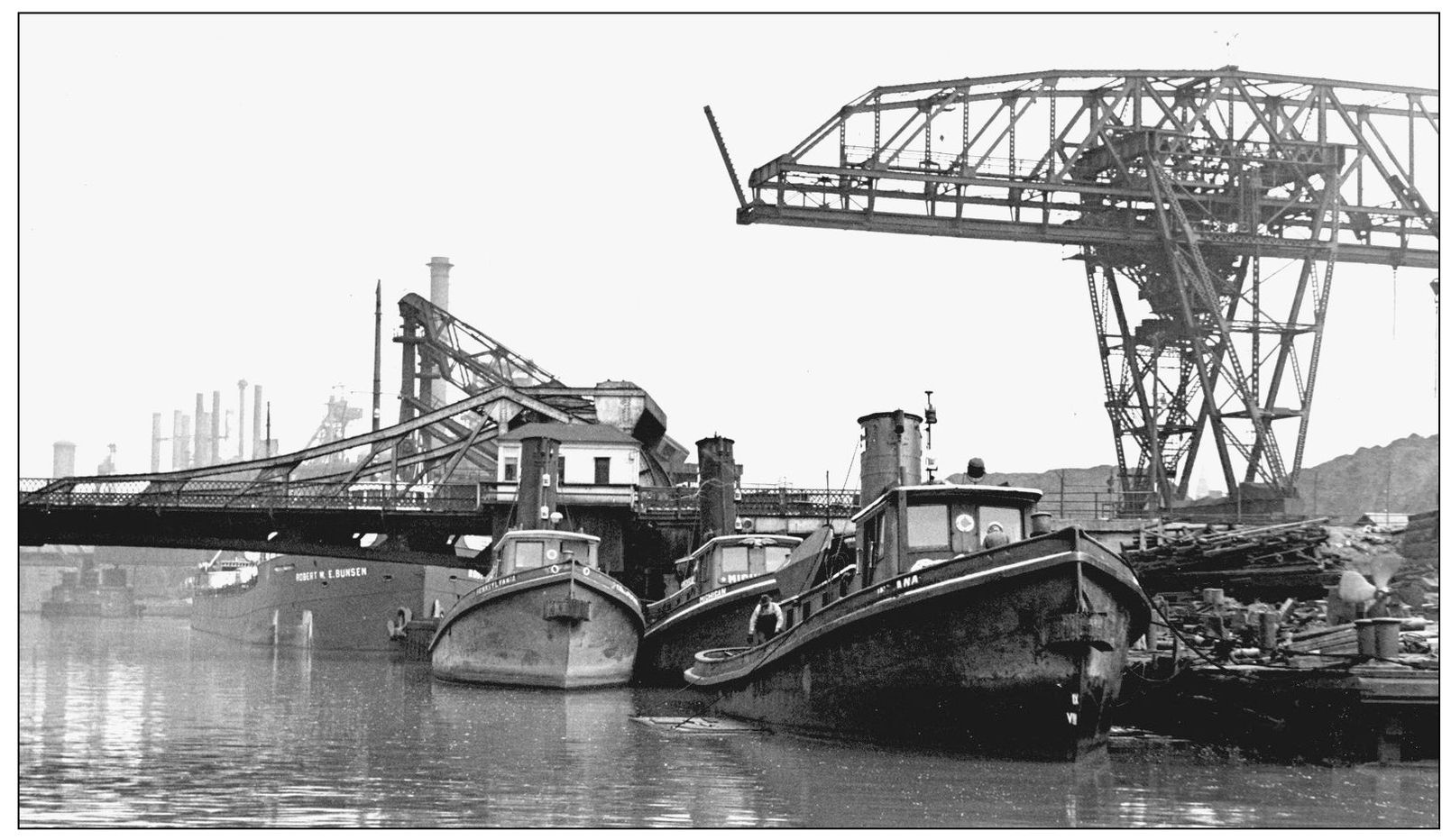

A trio of Great Lakes Towing Company tug boats almost appears to be guarding the 439-foot-long Robert W. E. Bunsen as it is unloaded by Huletts. The Bunsen was built in 1900 and worked for the United States Steel fleet for over 50 years. It spent its last days before scrapping in 1973 as a grain storage boat in New Orleans. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

Clevelanders who grew up near the Flats became accustomed to the billows of industrial smoke that emanated from the valley below. While all of the discharge coming from Republic Steel’s stacks made drying clothes outdoors difficult, most folks were willing to put up with sooty linens if it meant they and their neighbors were employed. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

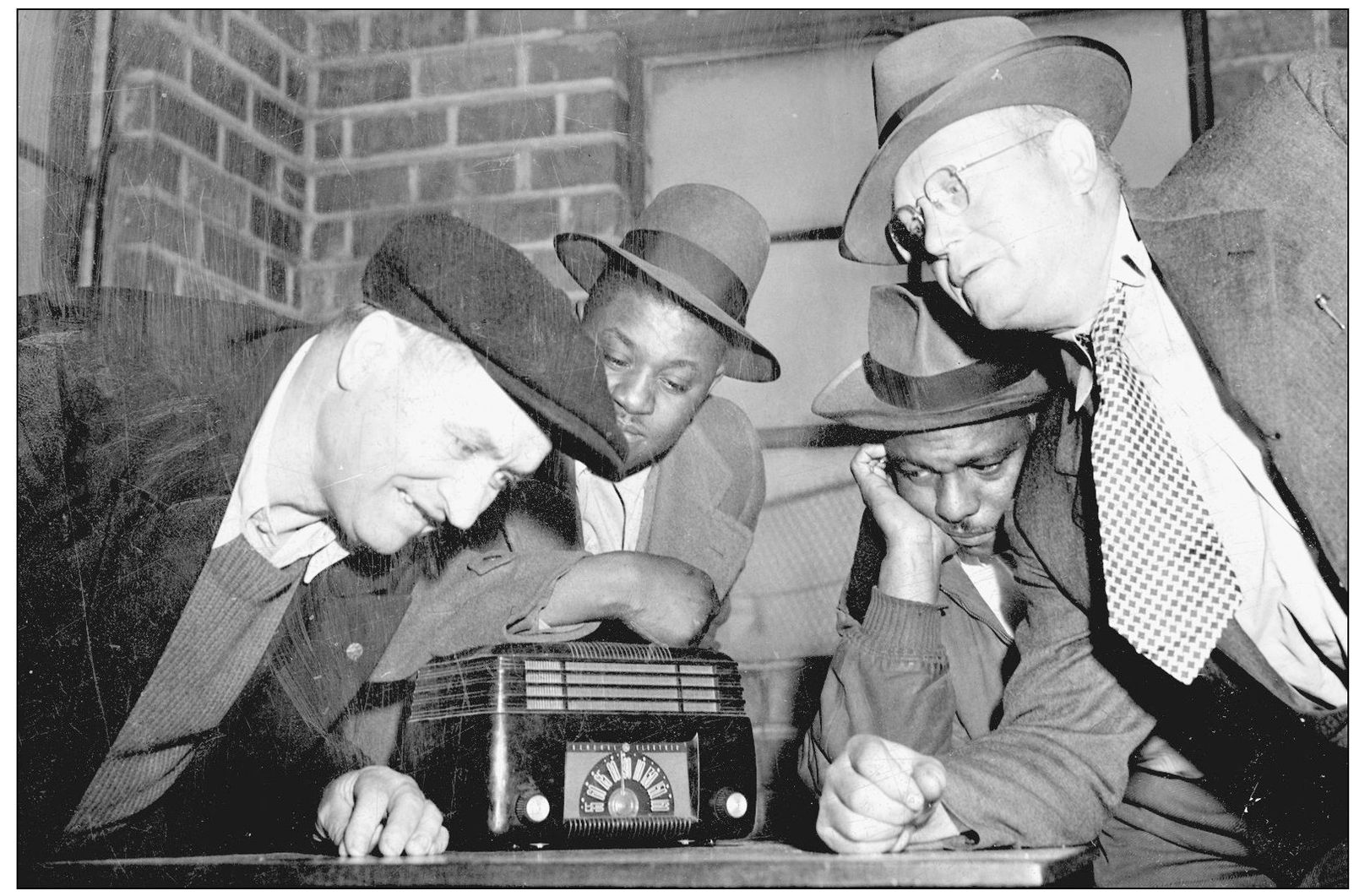

Strikes were a rather frequent occurrence at Republic Steel throughout the late 1940s and 1950s. None would reach the proportions of the 1937 strike, however, as disputes would be resolved without bloodshed. This group of Republic Steel strikers is eagerly listening to the radio for any news regarding their situation. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

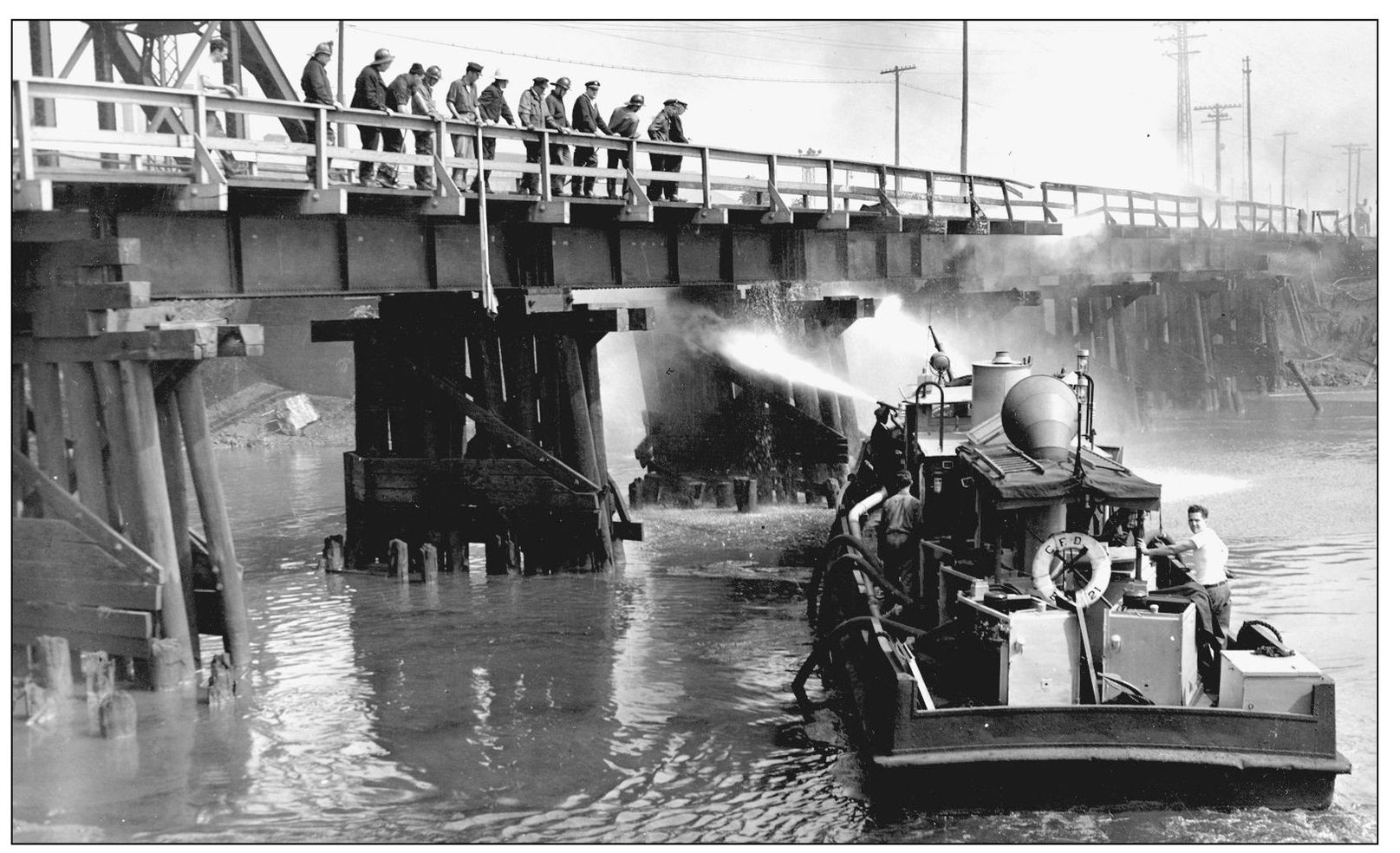

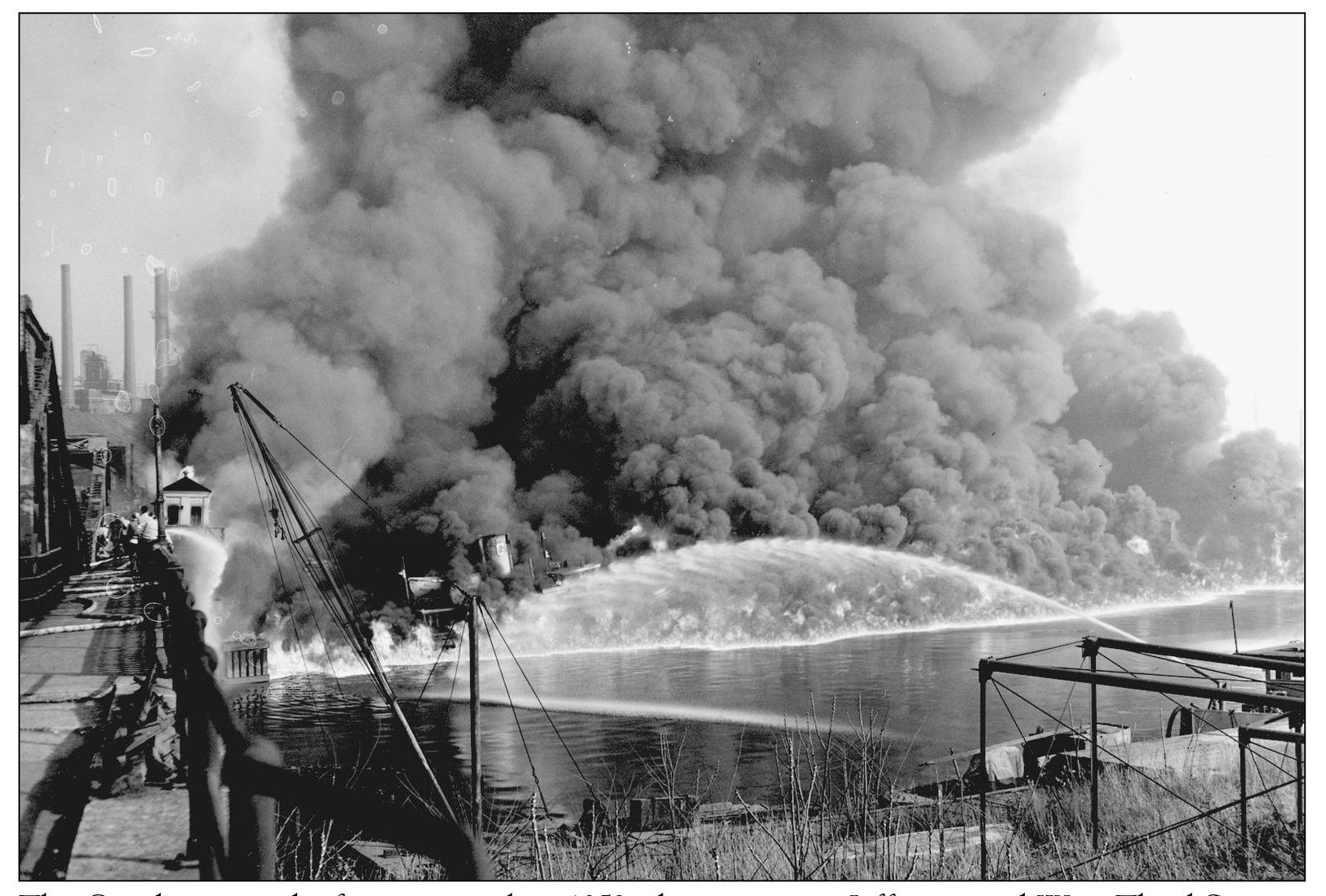

Unfortunately, strikes have not been the only regular event in the Flats. The Cuyahoga erupting into flame was also a somewhat commonplace situation throughout the 20th century. Oil and other chemicals would coagulate on the river’s surface, waiting for a stray spark or carelessly dispatched cigarette to ignite a blaze. Although a fire in 1969 would capture the attention of the nation, this particular blaze was photographed 20 years earlier. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

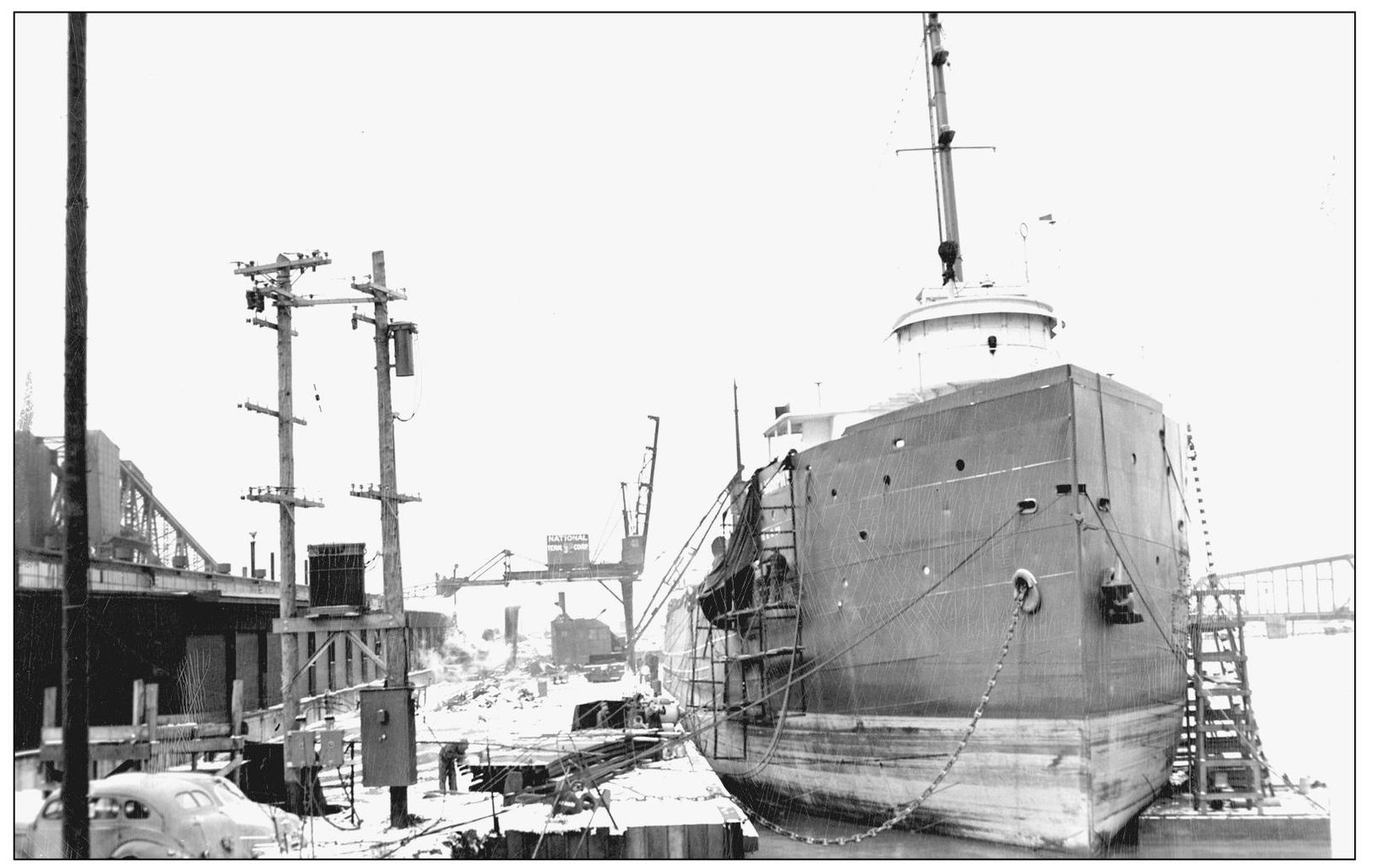

Workers tend to the steamer Simon J. Murphy in February 1950. The 435-foot-long Murphy would work for another 10 years after this image was taken before being scrapped on the old river bed of the Cuyahoga. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

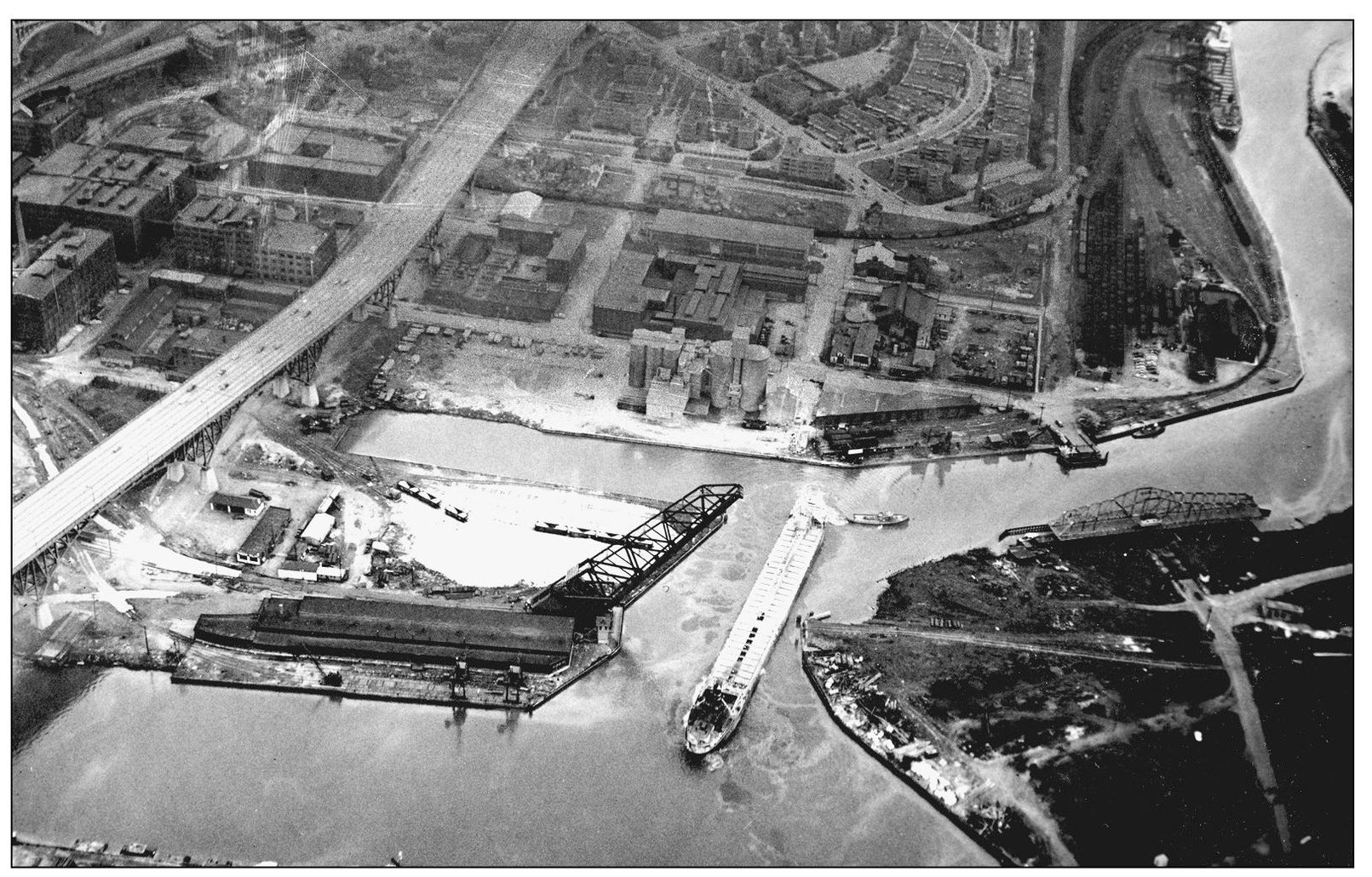

The laws of physics are again blatantly ignored as this lake boat maneuvers into the old channel of the Cuyahoga in the spring of 1950. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

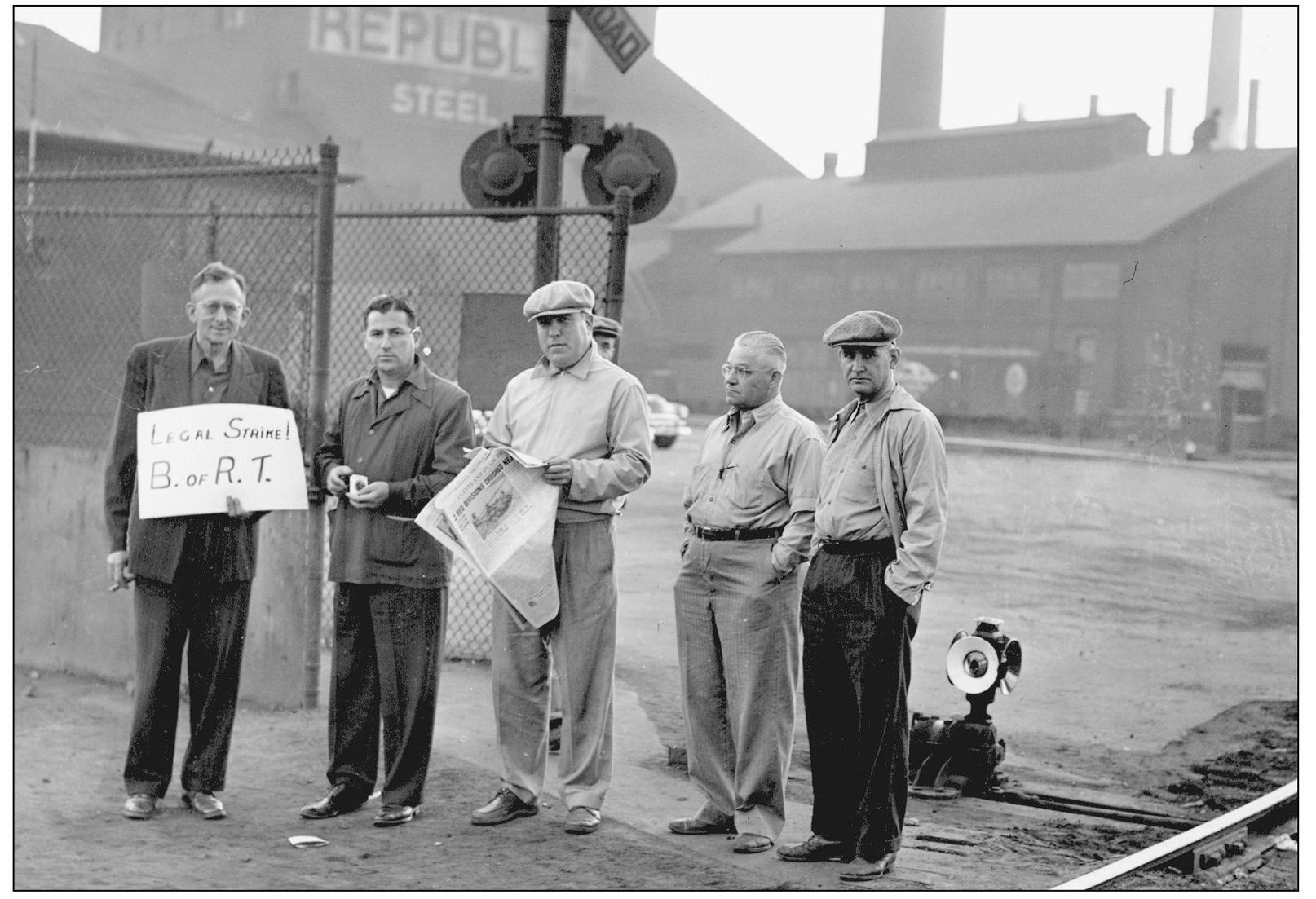

Pickets from the Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen stand outside of Republic Steel in August 1950. Also, the eagle-eyed reader will note the headline on the one gentleman’s Plain Dealer regarding events in Korea. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

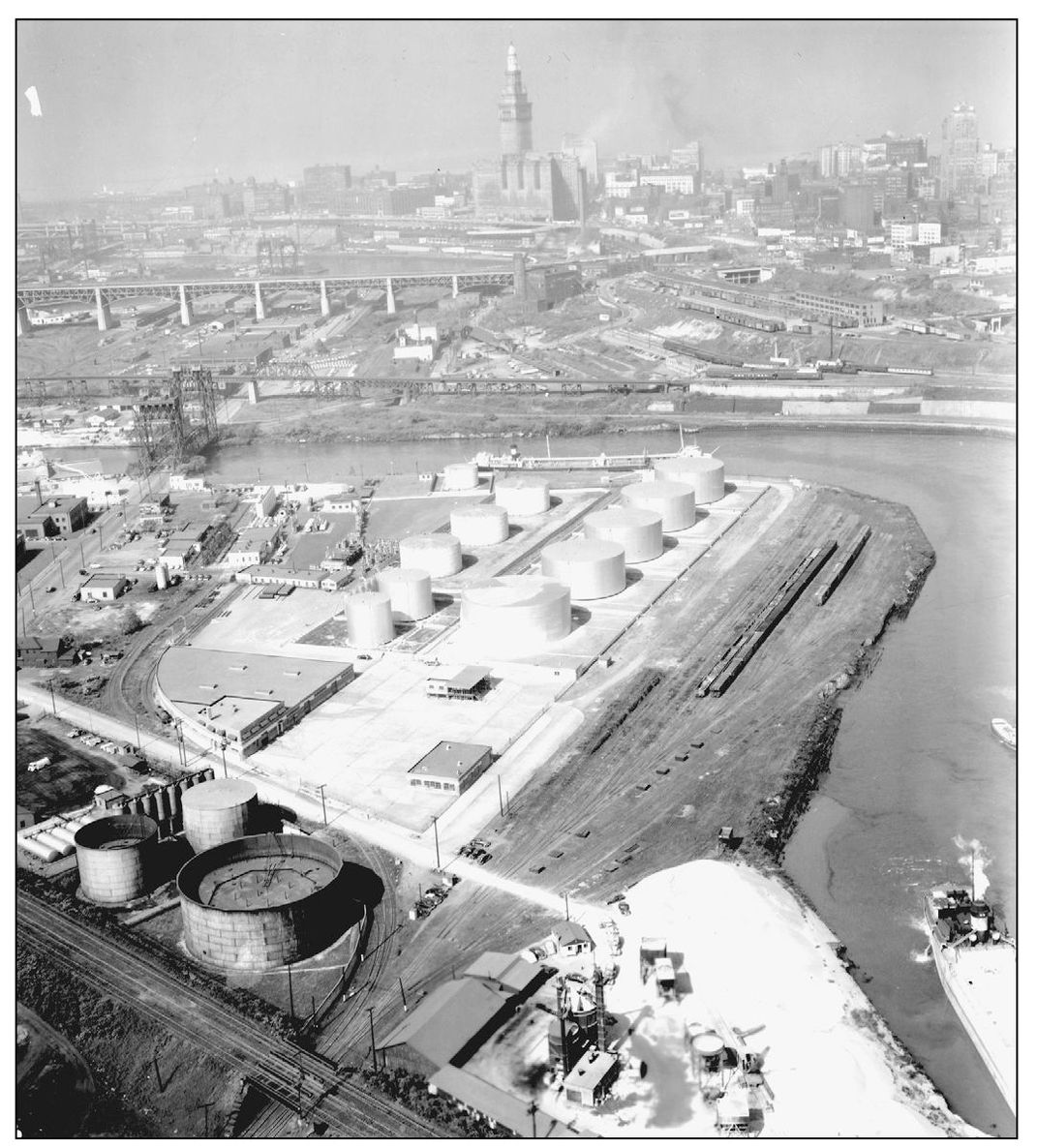

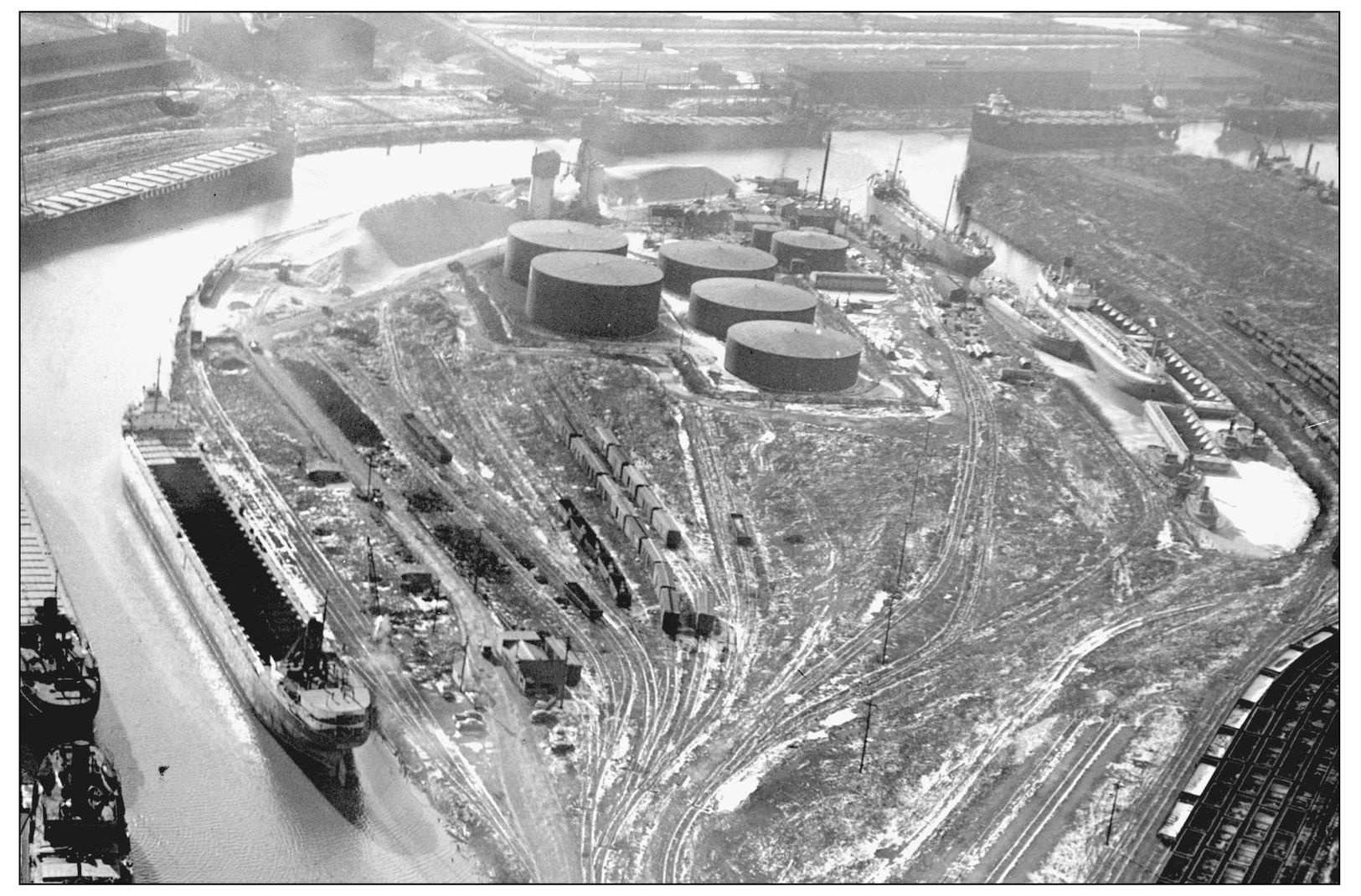

Standard Oil was not alone in the Flats as the Texas Company (Texaco) also had operations along the Cuyahoga. To the lower left in this image is a gasoline storage tank. The top of the tank is actually floating atop the gasoline inside. If the tank had a conventional cover, fumes could accumulate inside increasing the risk for a catastrophic explosion. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

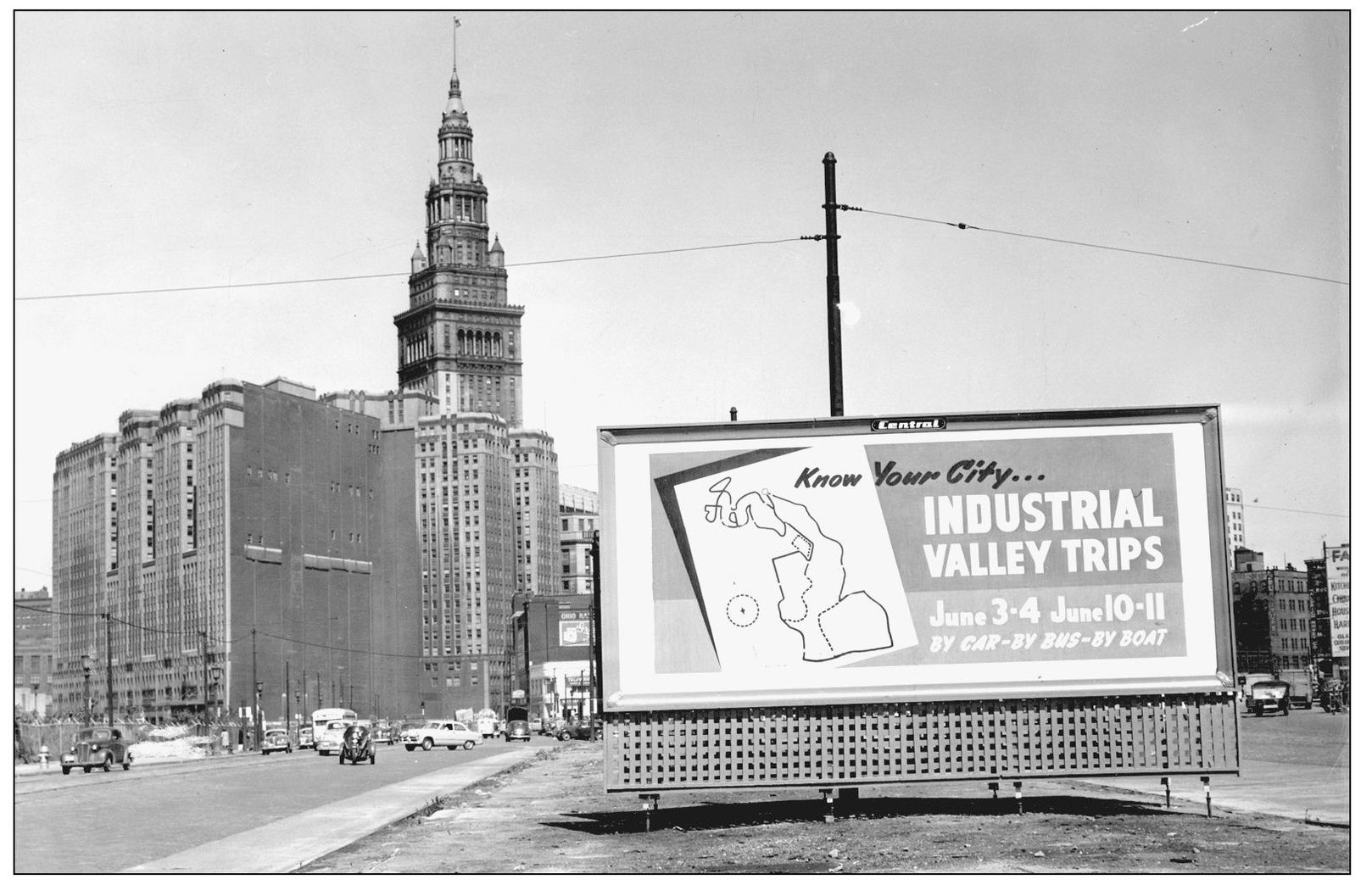

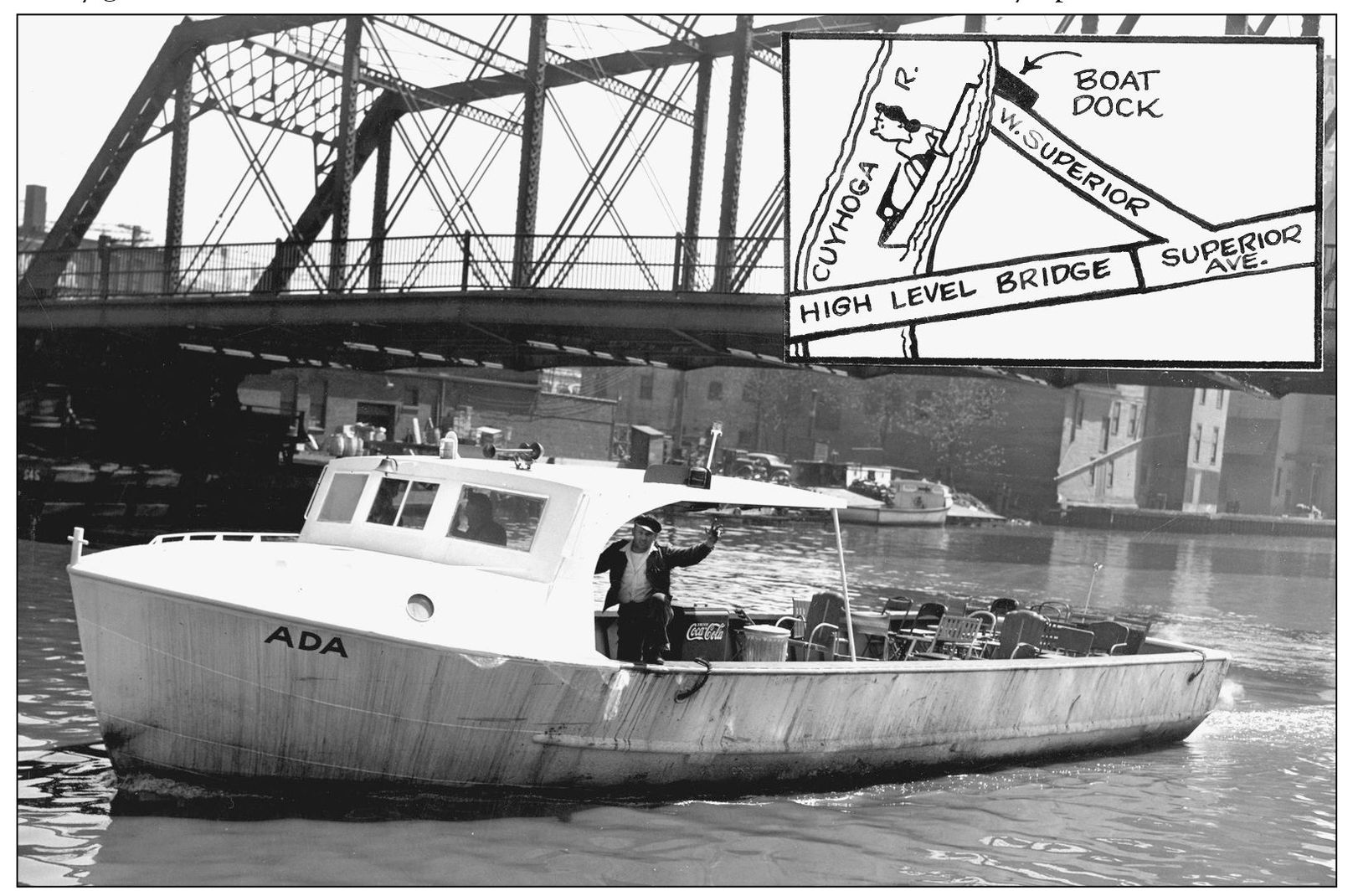

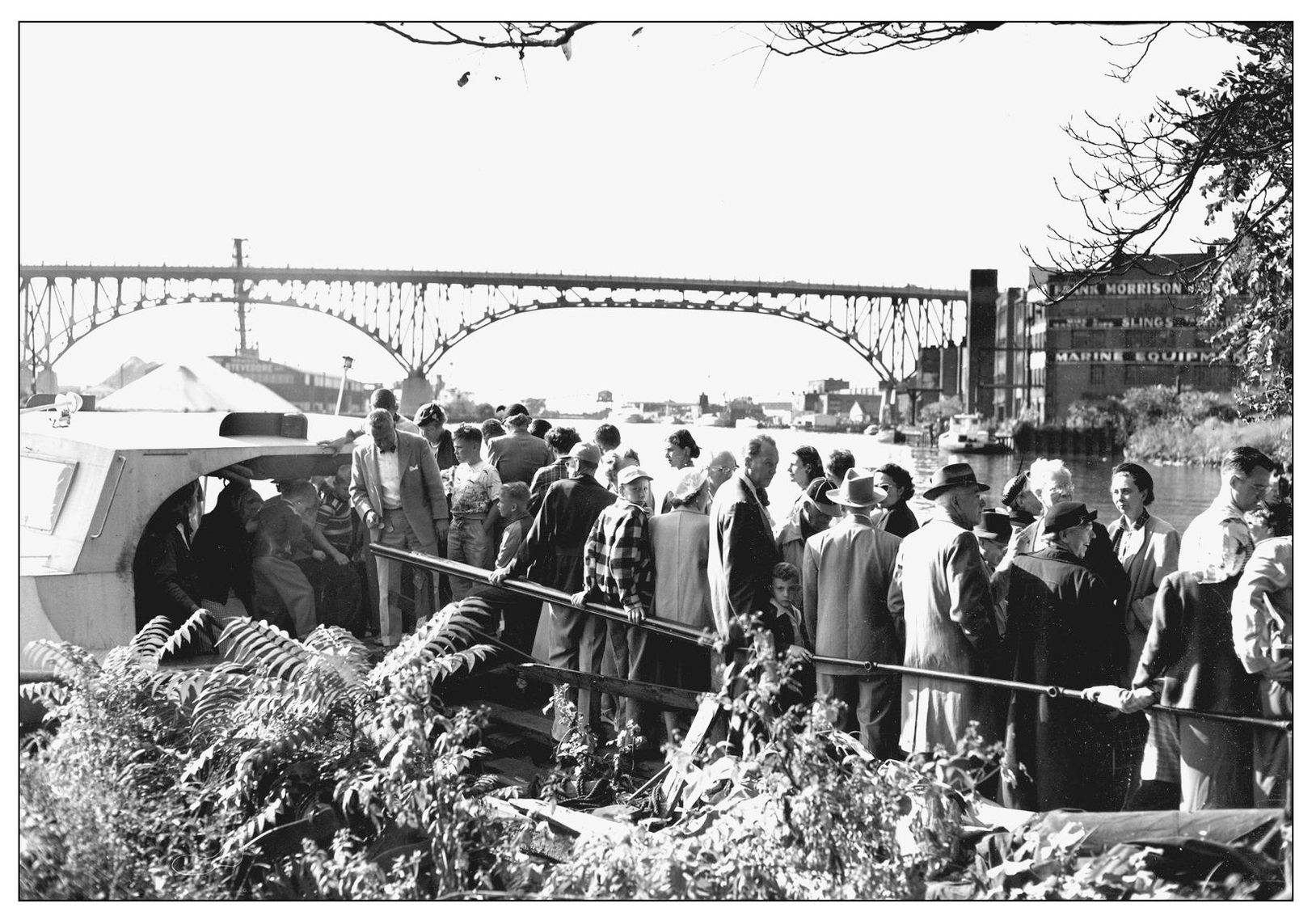

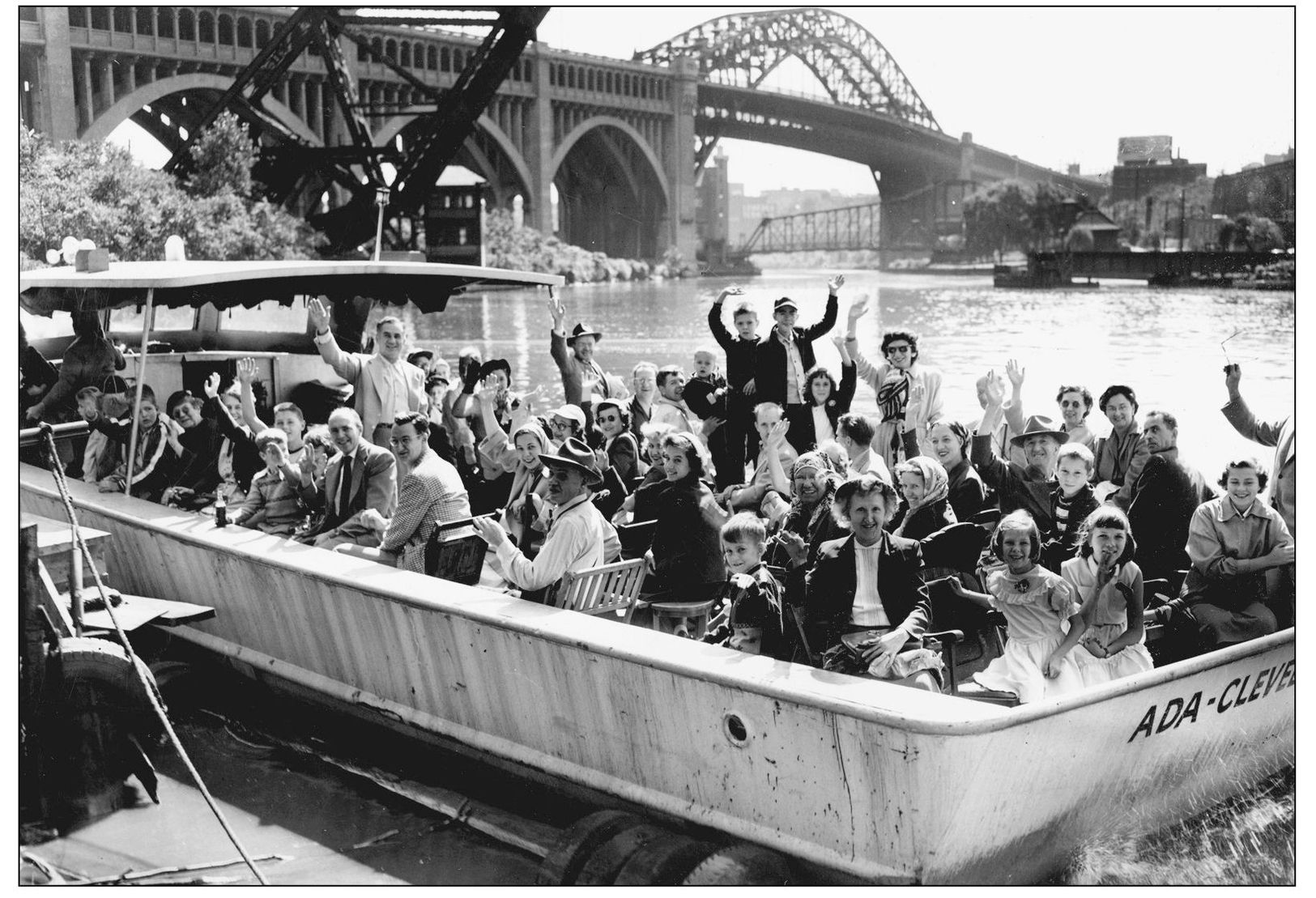

The Cleveland Press sponsored a number of Industrial Valley Trips in the 1950s. People taking the tours could drive themselves by following tour markers and instructions printed in the Cleveland Press, board buses, or float along the Cuyahoga in excursion boats. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

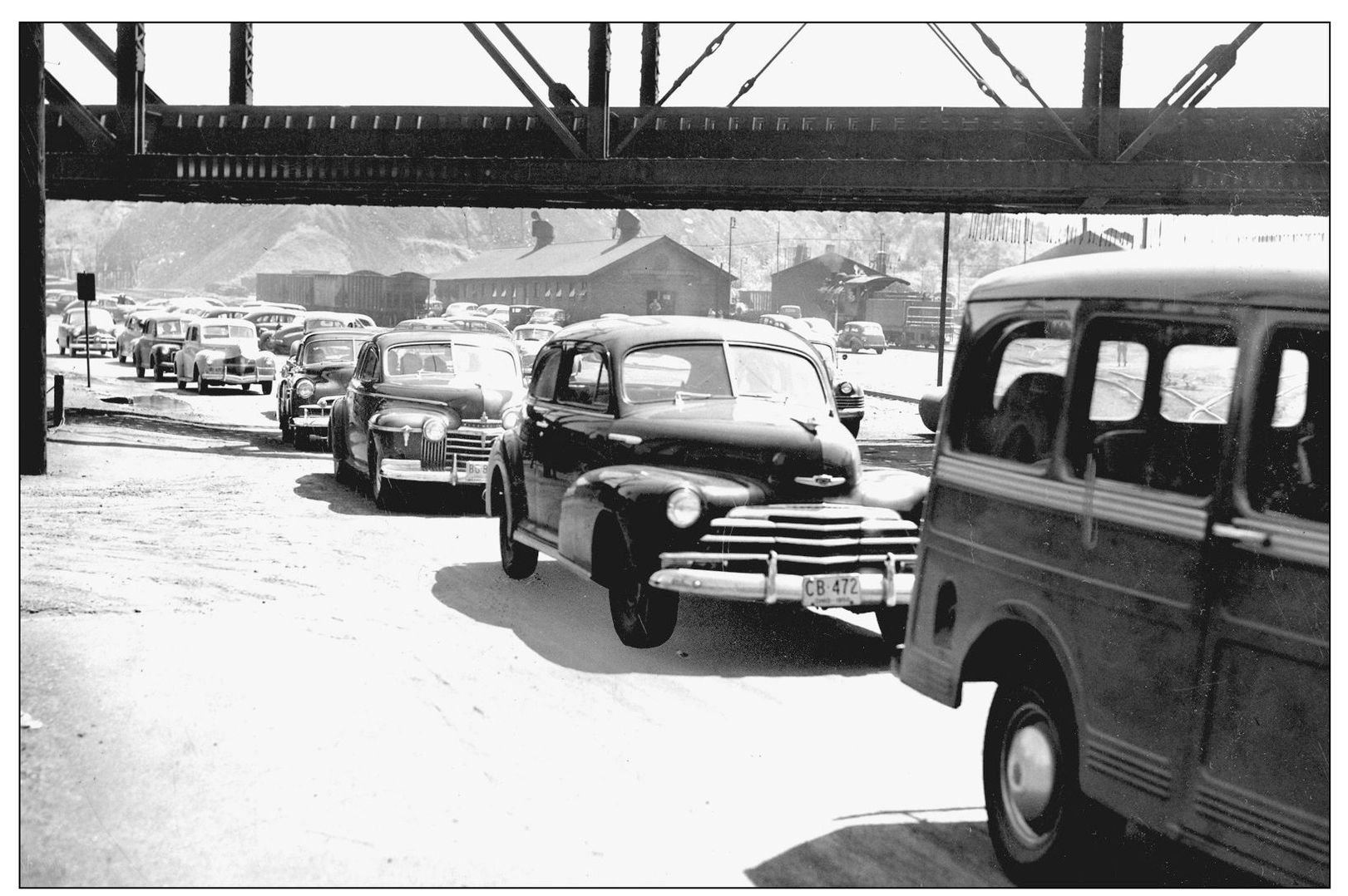

A group of cars departs the Terminal Railway repair shop under the Clark Avenue Bridge at the start of an Industrial Valley Trip. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

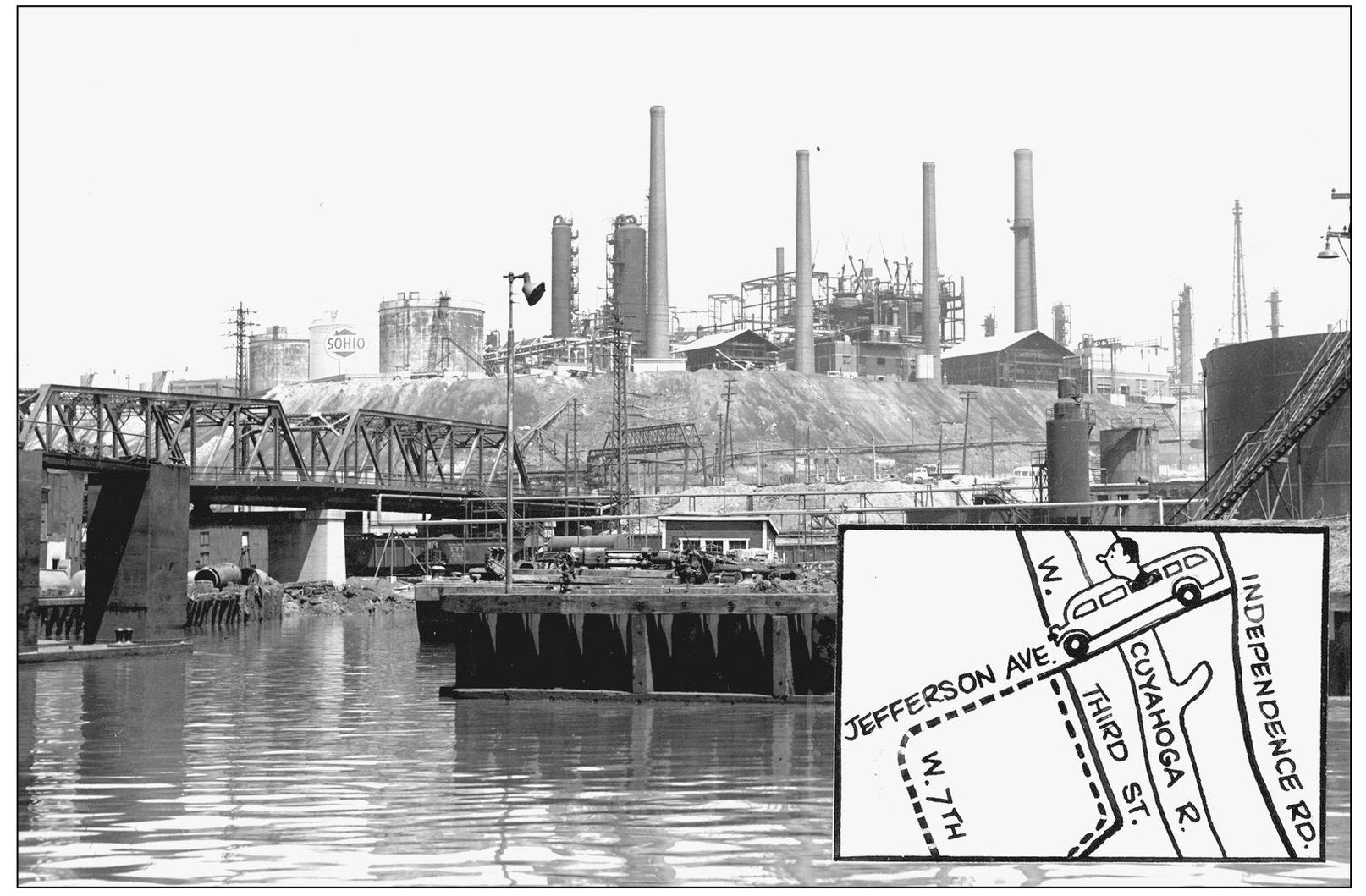

Tourists following the Industrial Valley route could get a good view of Standard Oil’s refinery located near West Third Street. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

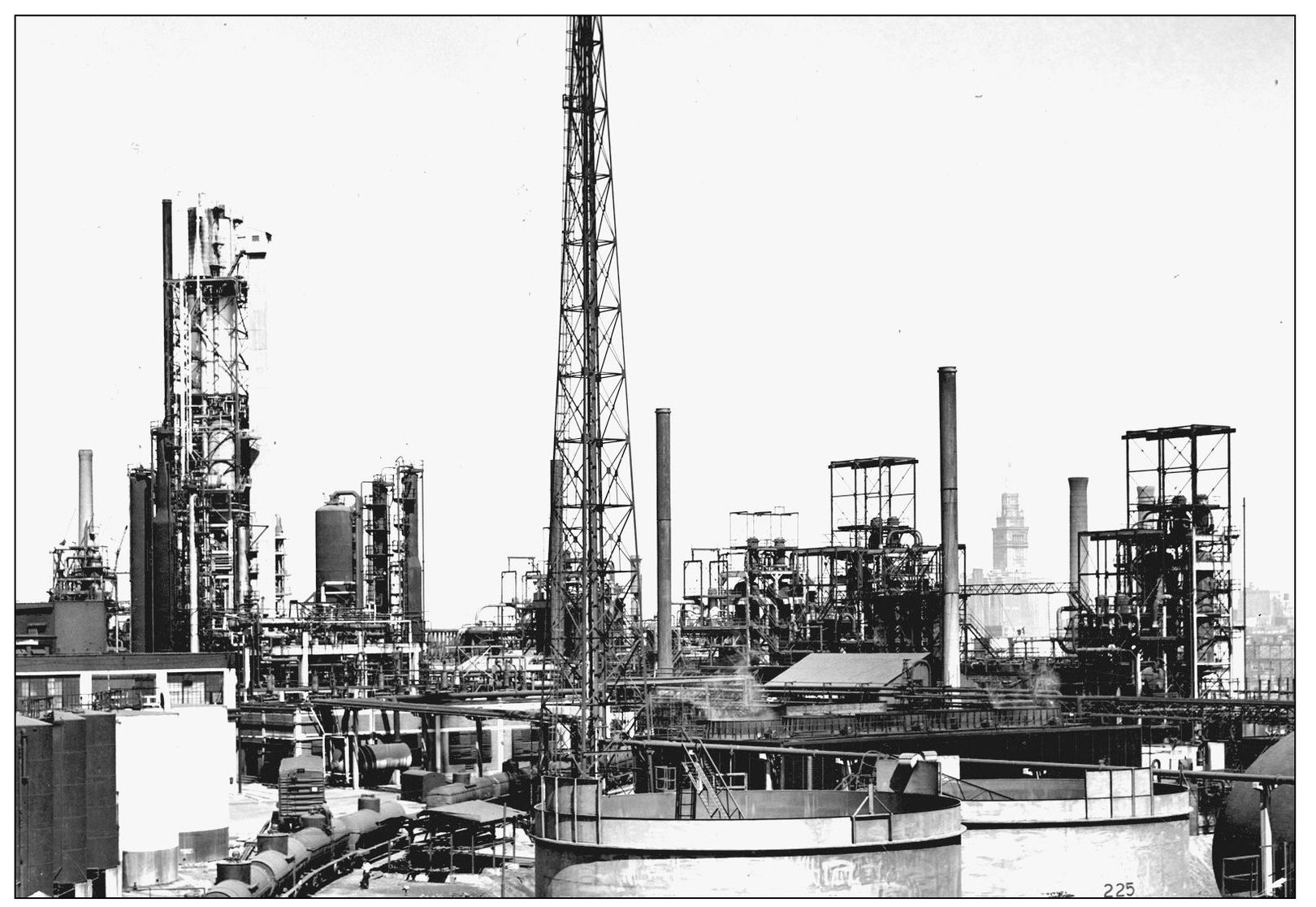

Pictured here is another view of Standard’s Cleveland works as they appeared in 1951. One can barely see the Terminal Tower to the right through the mass of derricks, pipes, and tanks. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

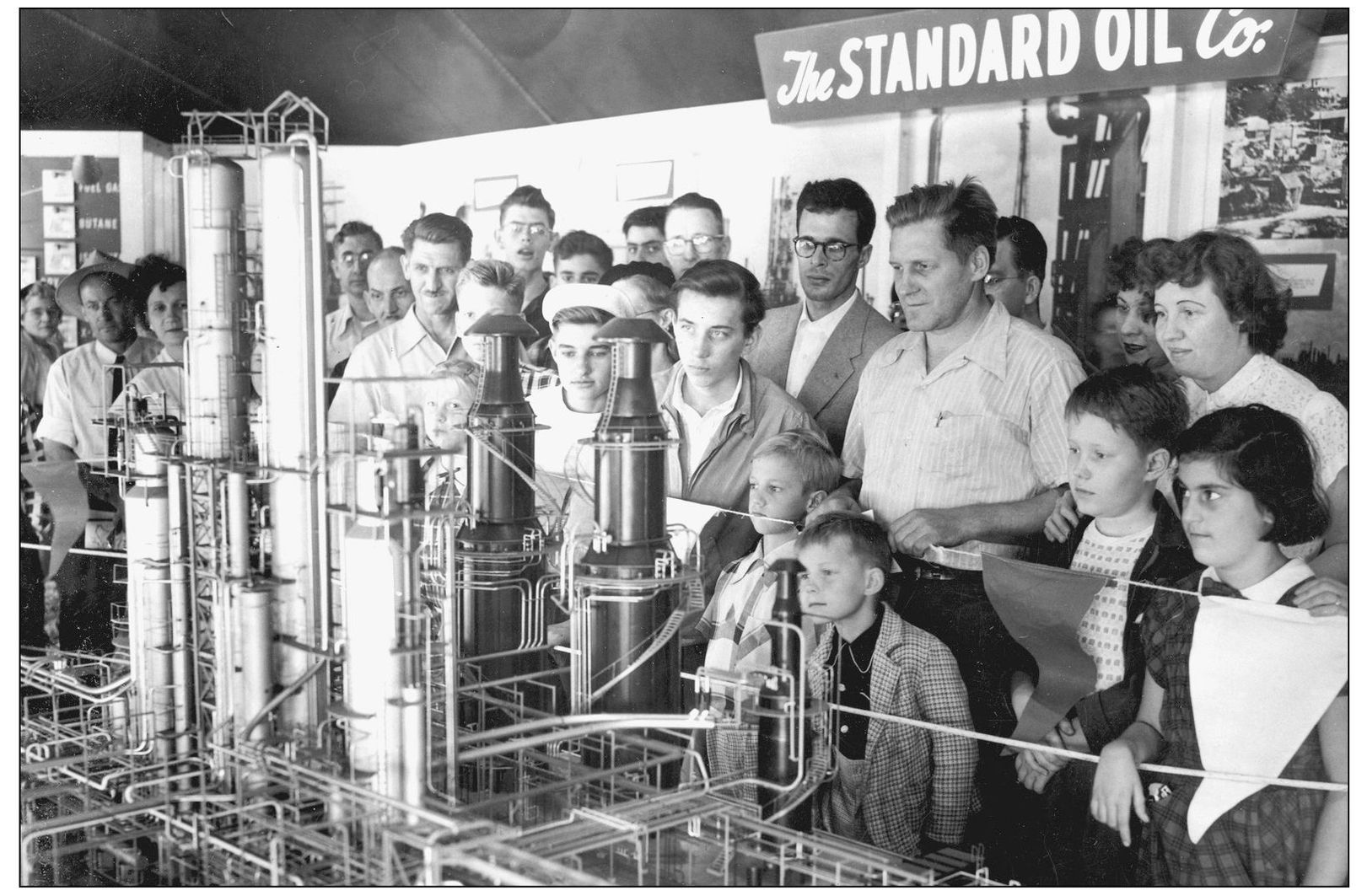

These Industrial Valley tourists are studying a model of Standard Oil’s number one refinery. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

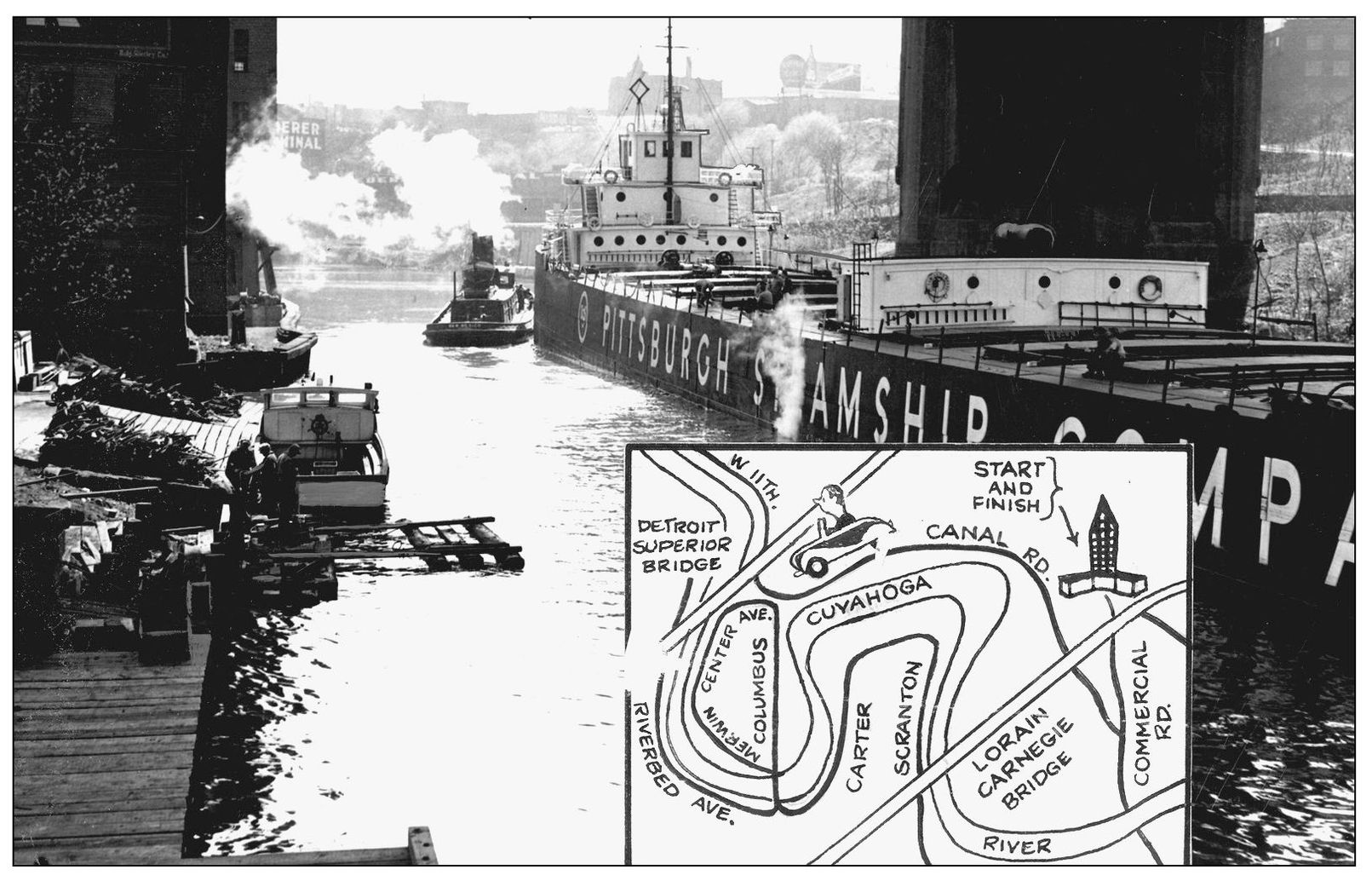

The Industrial Valley Trips would also give folks a chance to see sights such as this, a Pittsburgh Steamship Company (the U.S. Steel Company’s shipping fleet) boat navigating beneath the Detroit-Superior Bridge. At one point, PSC had over 100 vessels. Several of them had structures mid-ship, such as the one on this boat. This small deckhouse would serve as an extra dining room if any guests should be aboard. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

Capt. Johnny Skrovan waves for the camera as he prepares to take on Industrial Valley sightseers aboard his boat Ada. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

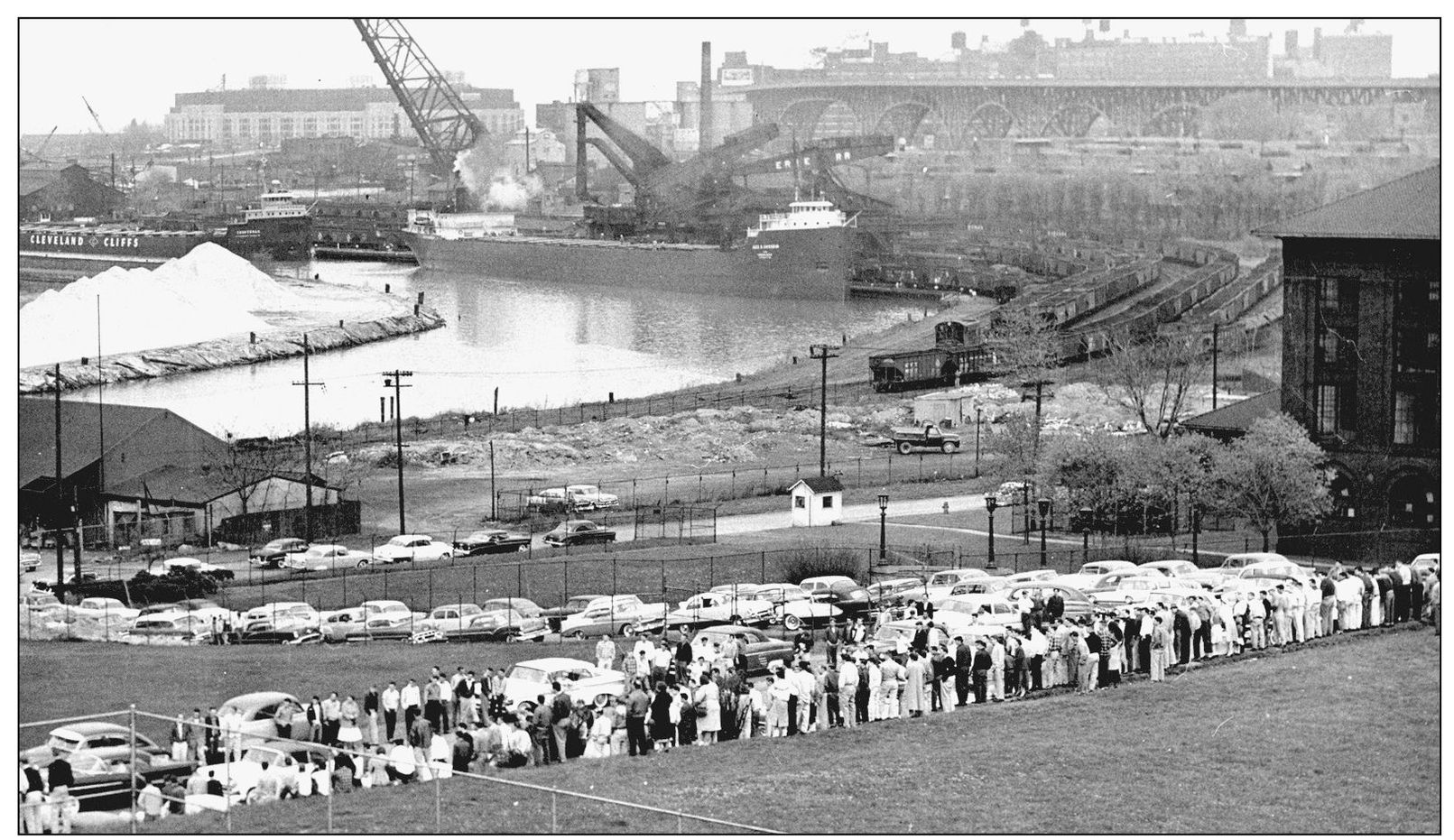

Passengers line up on the east bank of the Flats to board Ada. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

A capacity crowd fills Ada for a tour of the Cuyahoga. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

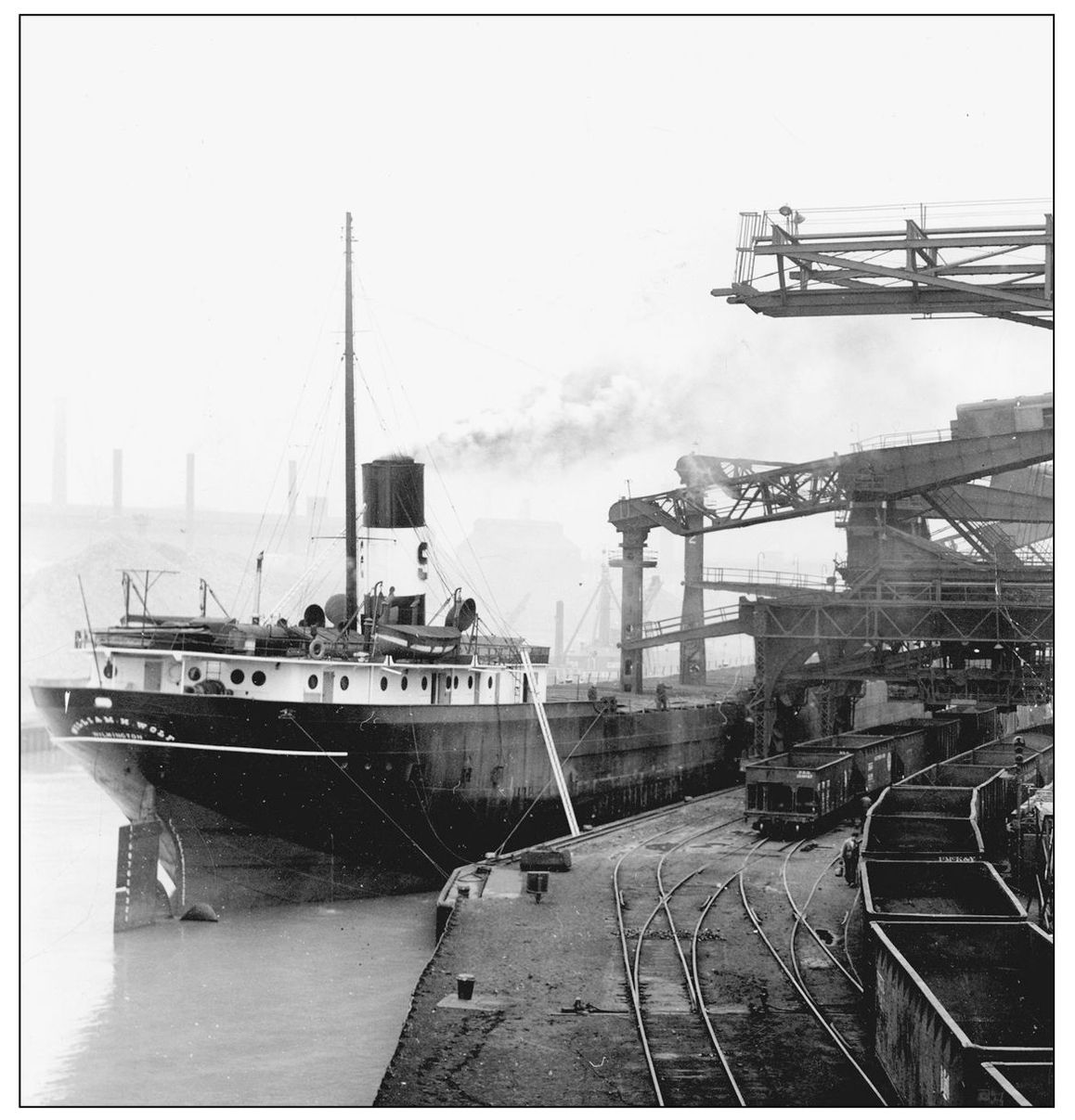

A set of Huletts are at work in the holds of the 504-foot-long William H. Wolf. The 10,000 tons of iron ore that the Wolf took on at Escanaba, Michigan, was loaded into Nickel Plate Railroad cars bound for Massilon, Ohio. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

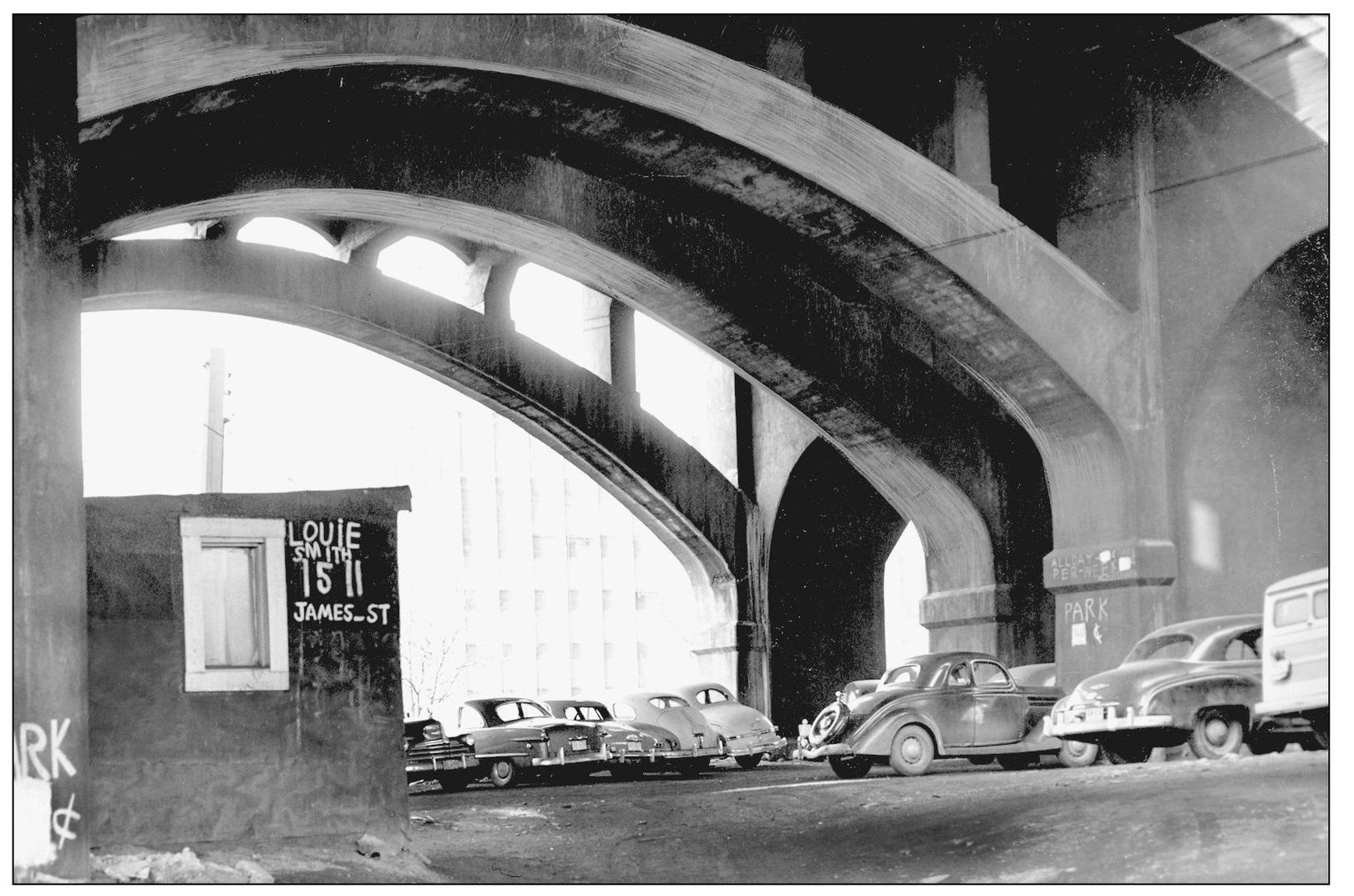

Park at Louie’s! Located underneath the Detroit-Superior Bridge, Louie Smith’s parking lot afforded automobiles some shelter from the elements. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

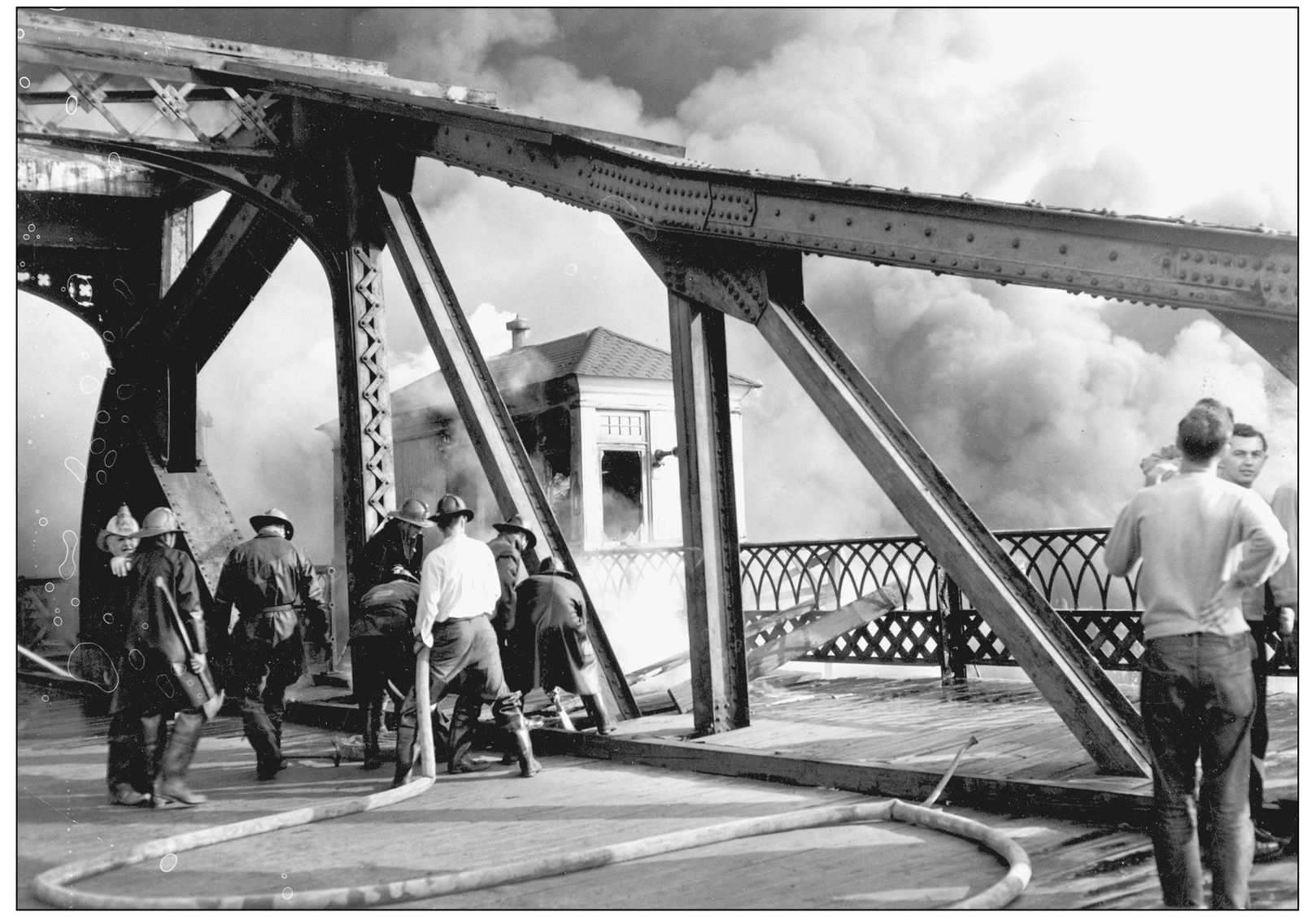

Firemen work to extinguish another blaze along the Cuyahoga in this 1951 image. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

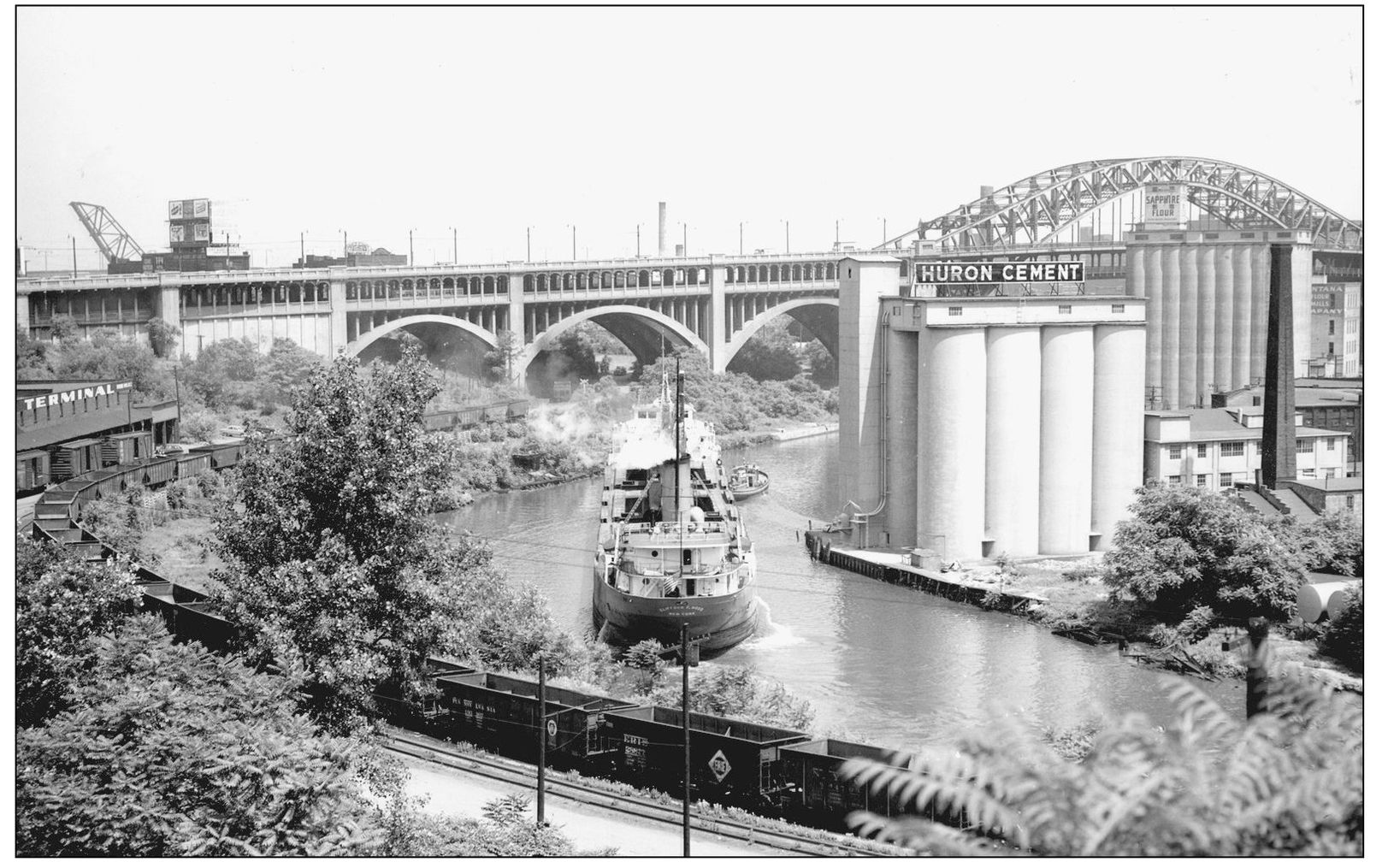

Huron Cement once had a cement dock at the Irish Town Bend. As the Clifford Hood demonstrates, however, the site that Huron’s facilities occupied made navigation somewhat more challenging. And, at 421 feet long and 50 feet wide, the Hood was actually among the smaller ships working when this image was taken in 1952 so one can imagine the trouble larger boats had. Cleveland voters would approve a $2 million issue to move Huron to another location and then widen the river. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

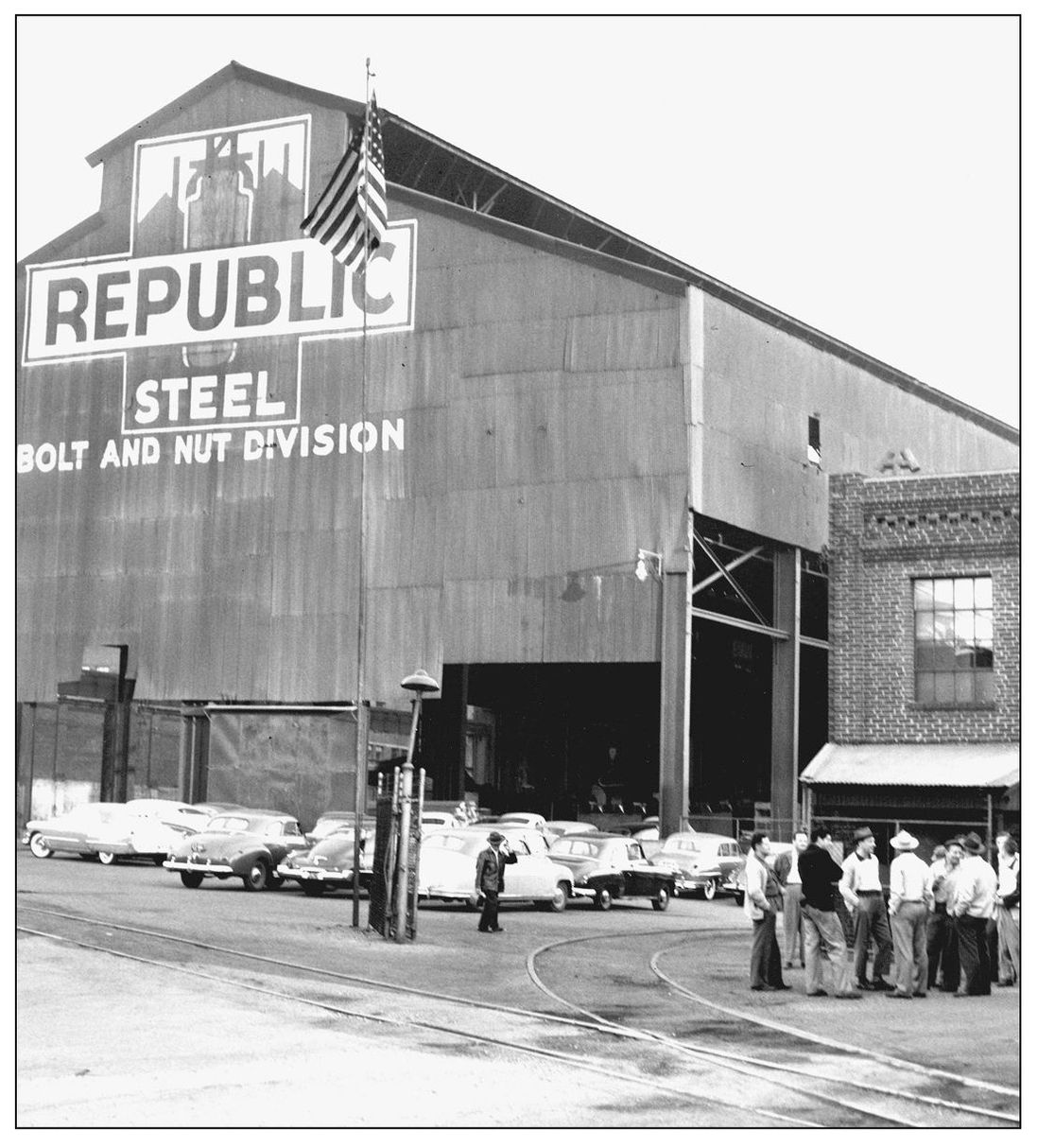

Labor troubles would again plague Republic Steel in May 1952. A group of striking workers met while the last man out of the Bolt and Nut Division tipped his hat. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

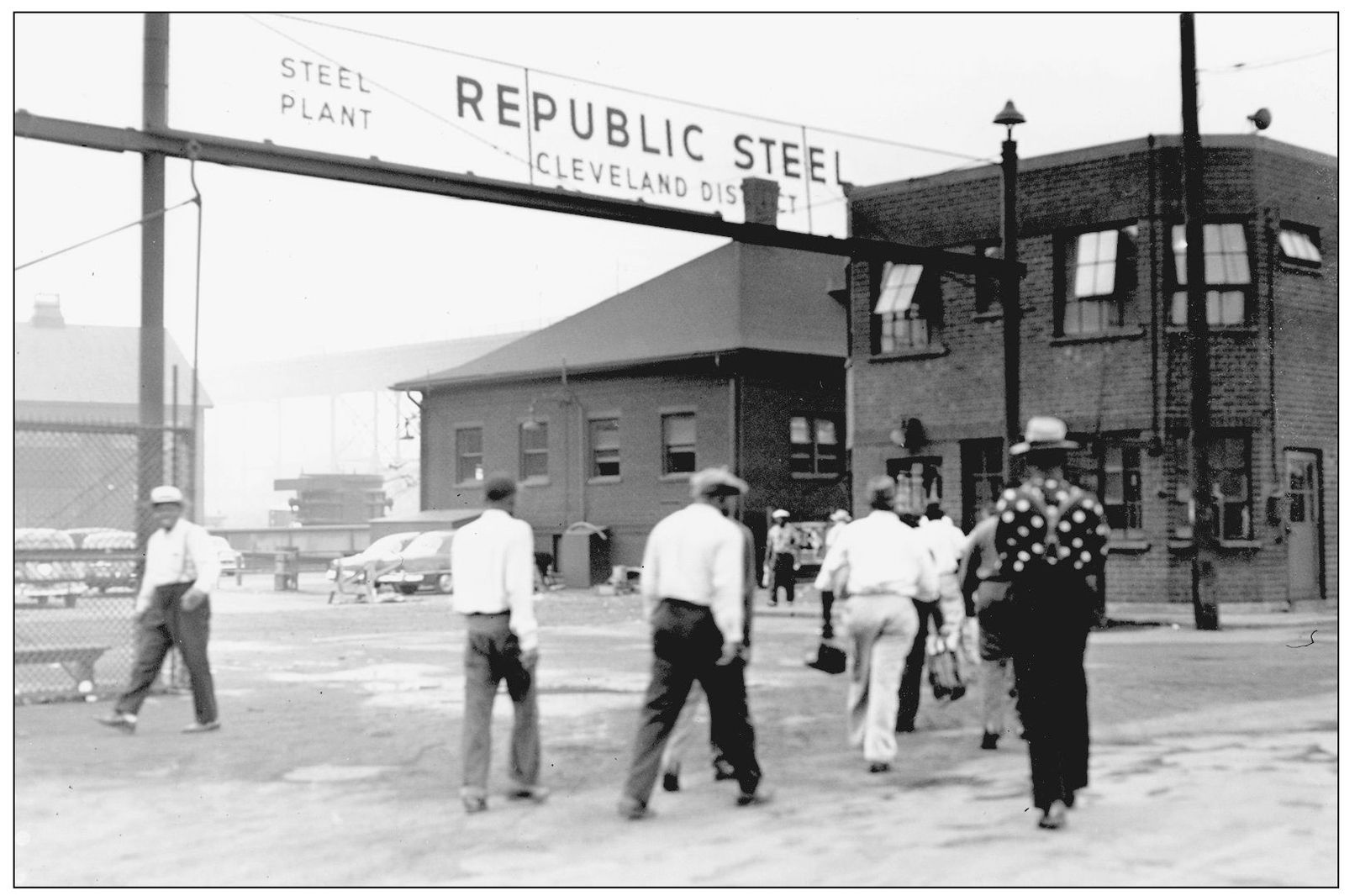

By July 1952, the steelworkers and Republic Steel had resolved their differences and employees would again filter through the gates. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

The Cuyahoga caught fire again in late 1952, this time near Jefferson and West Third Streets. Firefighters struggle against the flames and thick smoke while a Great Lakes tug boat lies helpless in the water. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

Picture here is another view of the 1952 Cuyahoga River fire.

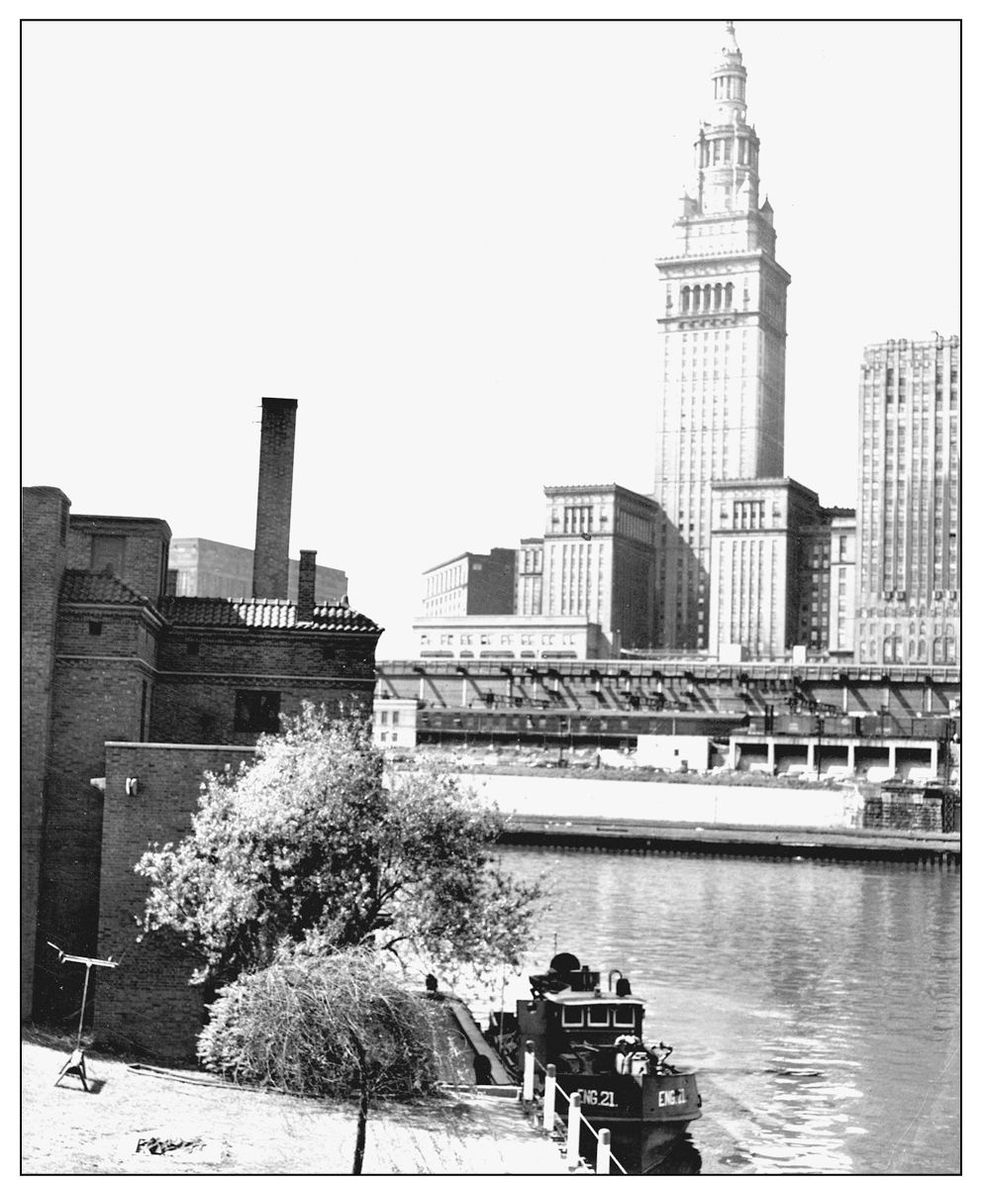

Cleveland’s fireboat moored next to Fire Station No. 21.

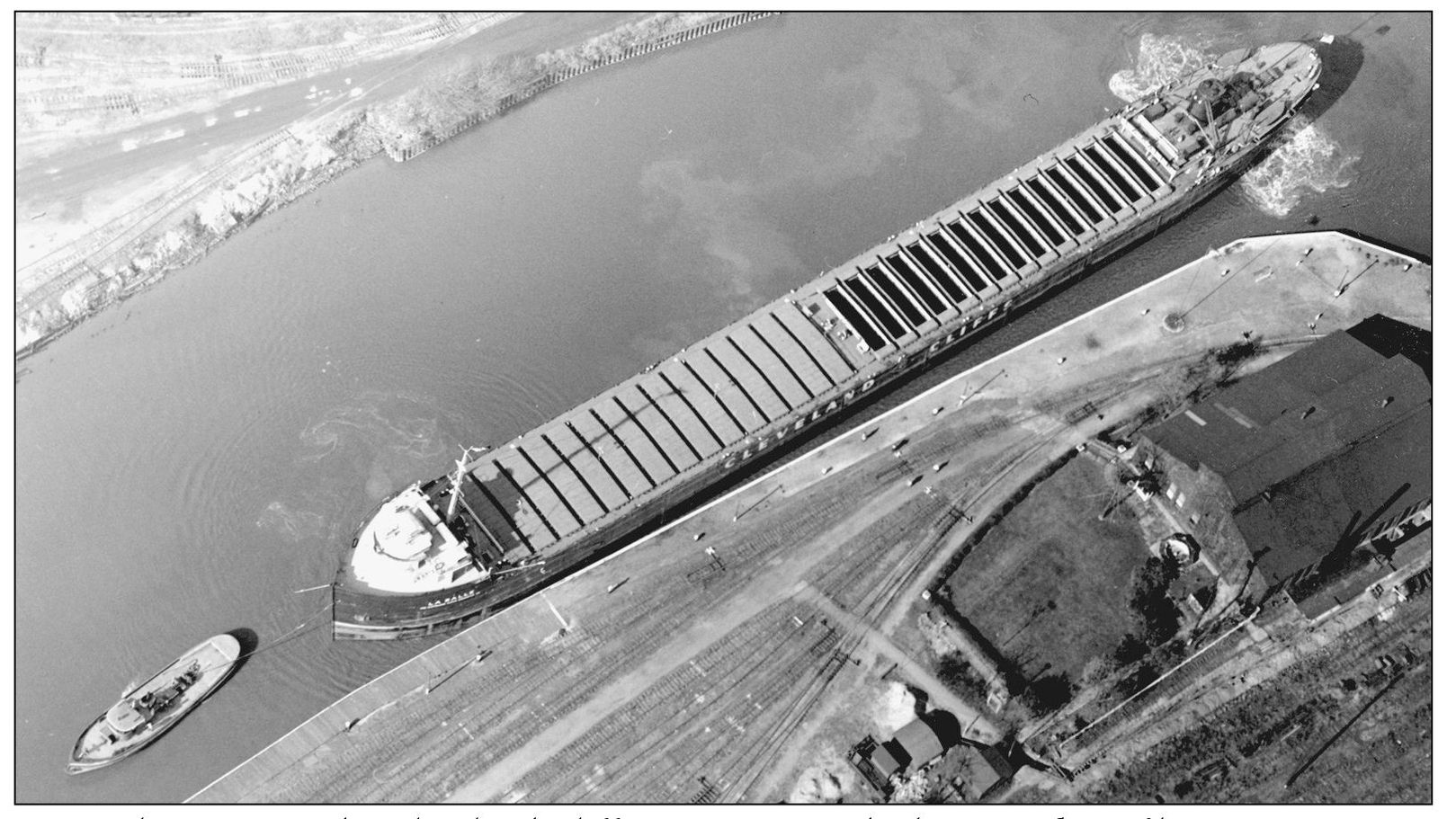

For nearly 100 years, the Cleveland-Cliffs Iron Company had its own fleet of boats to carry iron ore from ports such as Marquette, Michigan, to Cleveland. One of these boats was the steamer La Salle, a 550-foot-long vessel that had been built in 1906 and was originally named the J. H. Sheadle. By 1953, when this photograph was taken, the La Salle had many a sea story to tell, including the tale of the infamous 1913 “White Hurricane.” While the former Sheadle and its crew got through the tempest, over 200 sailors perished in what was perhaps the worst storm in Great Lakes’ history. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

Another Cleveland-Cliffs stalwart, the Peter White, is seen here. The White was built in 1905, measured in at 524 feet long, could carry 9,000 tons of cargo, and served in the Cleveland-Cliffs’s fleet until 1959. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

Winter takes hold along the Cuyahoga in 1954. The boat in lay-up near the bottom of the photograph is an early self-unloader, as evidenced by the discharge boom over its spar deck. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

A collection of boats is laid up along the old river bed of the Cuyahoga. Before the mid-19th century, this section had been the mouth of the river. Deemed an impediment to navigation, the old flow would be by-passed and a new much wider and straighter mouth was cut. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

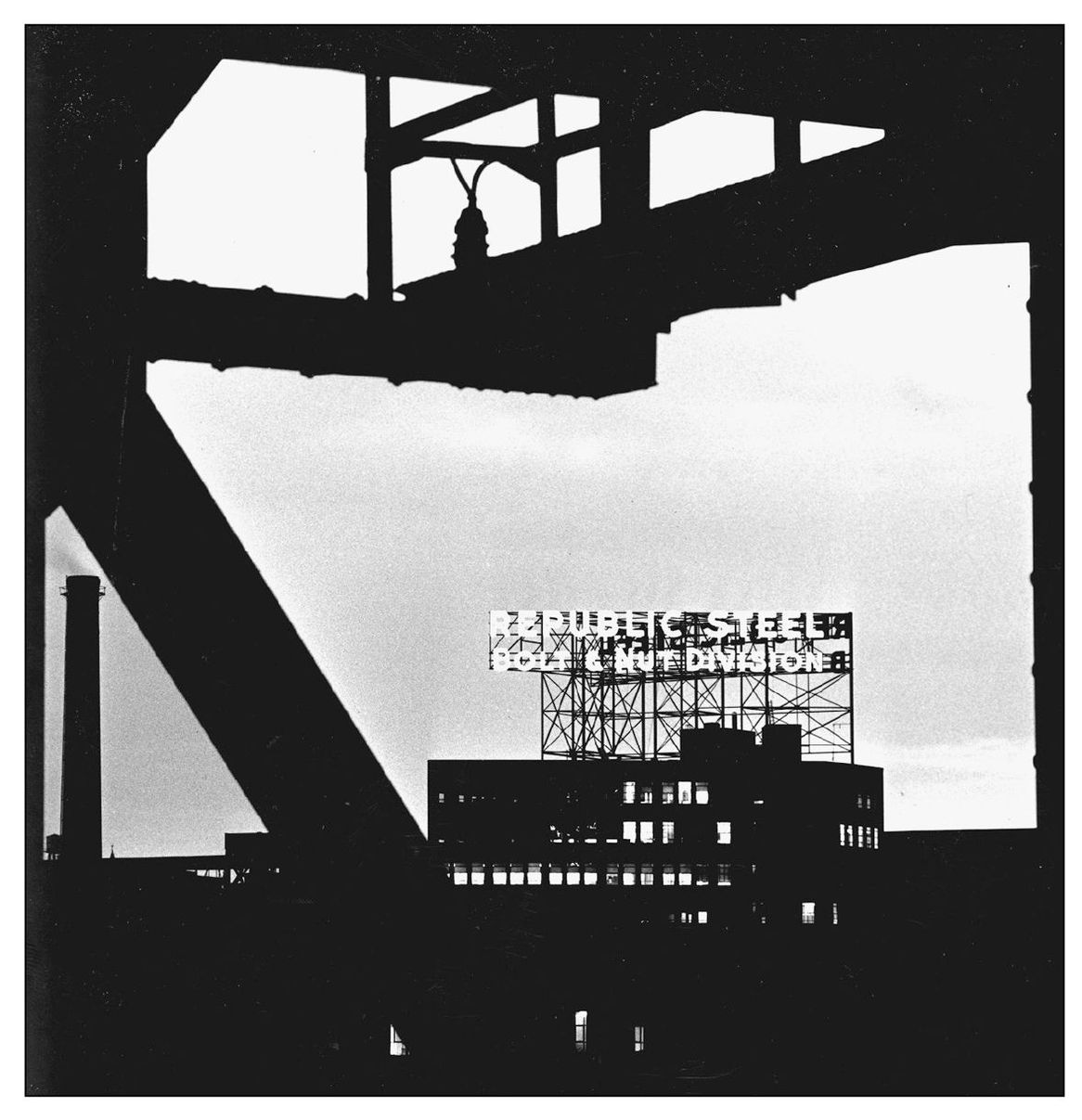

The large illuminated sign of Republic Steel’s Bolt and Nut Division stands proudly over the Flats on a summer evening in 1954. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

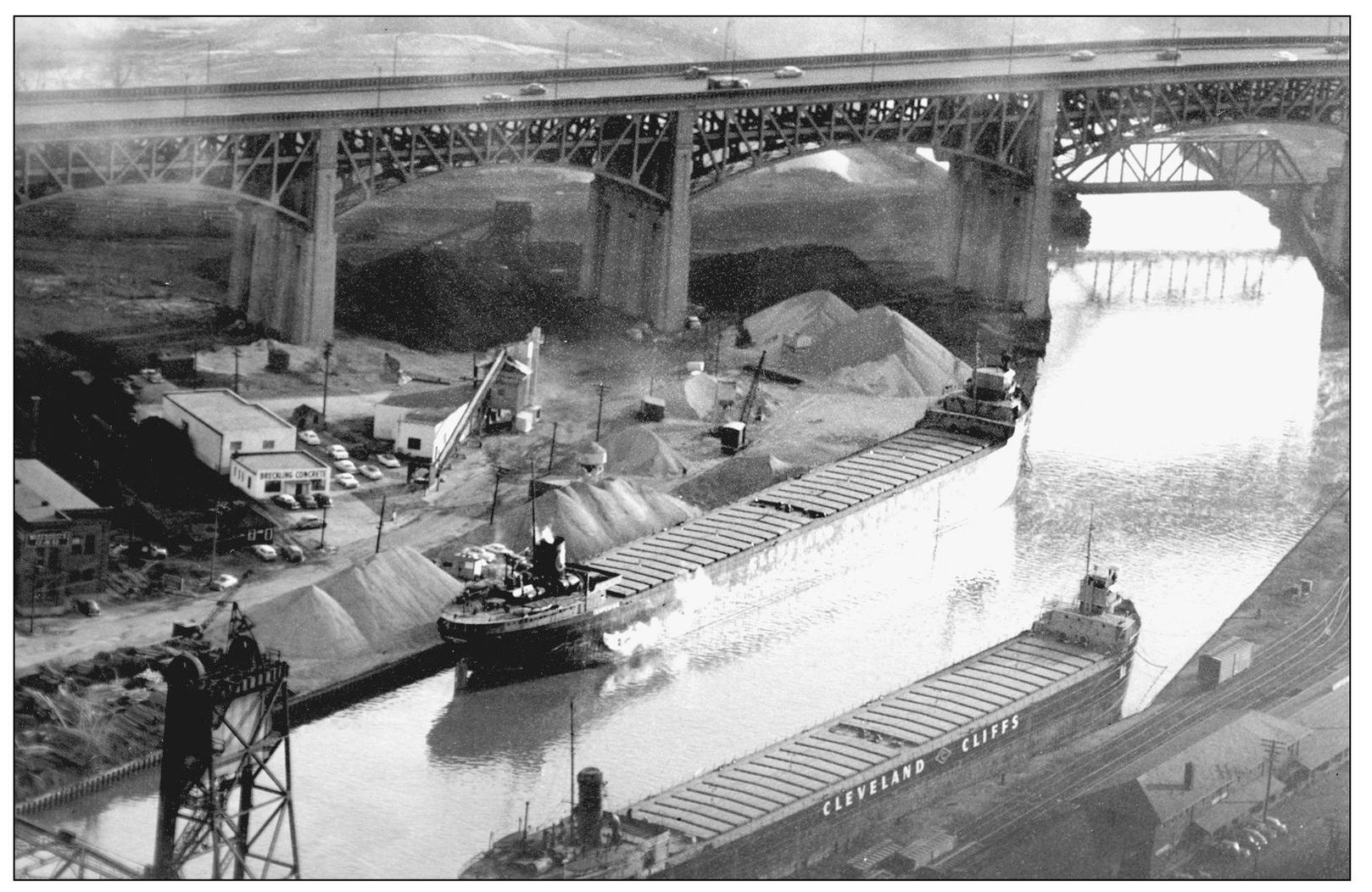

As cars travel over the Lorain-Carnegie Bridge, the Cleveland-Cliffs steamers Peter White and Ishpeming hibernate during the winter of 1955–1956. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

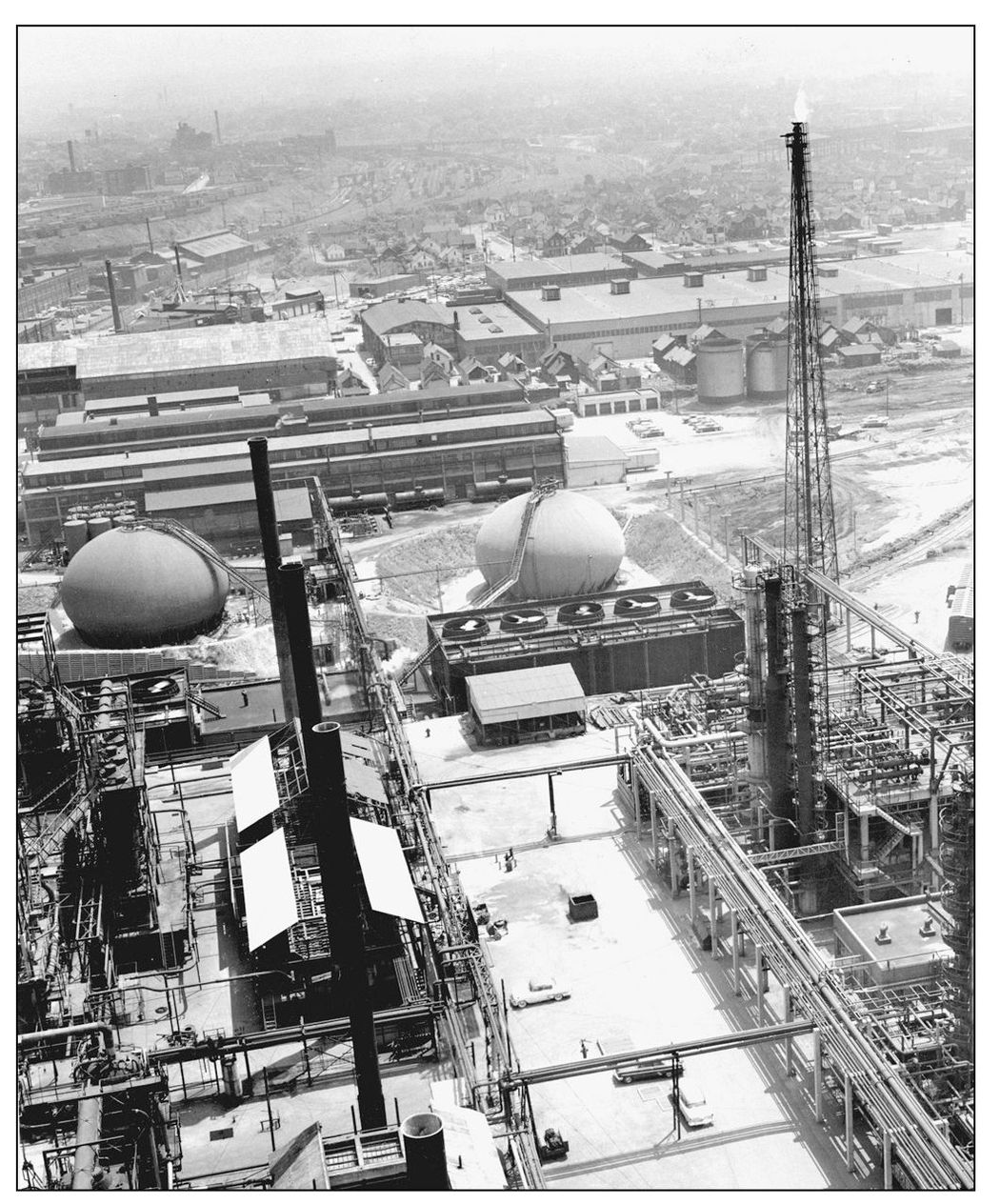

Some of the tools of the refining trade are seen in SOHIOs Cleveland works in 1955. Thermal cracking plants to the left share space with the gas plants on the right and the Horton spheroids, which were used to store butane gas, at the rear. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

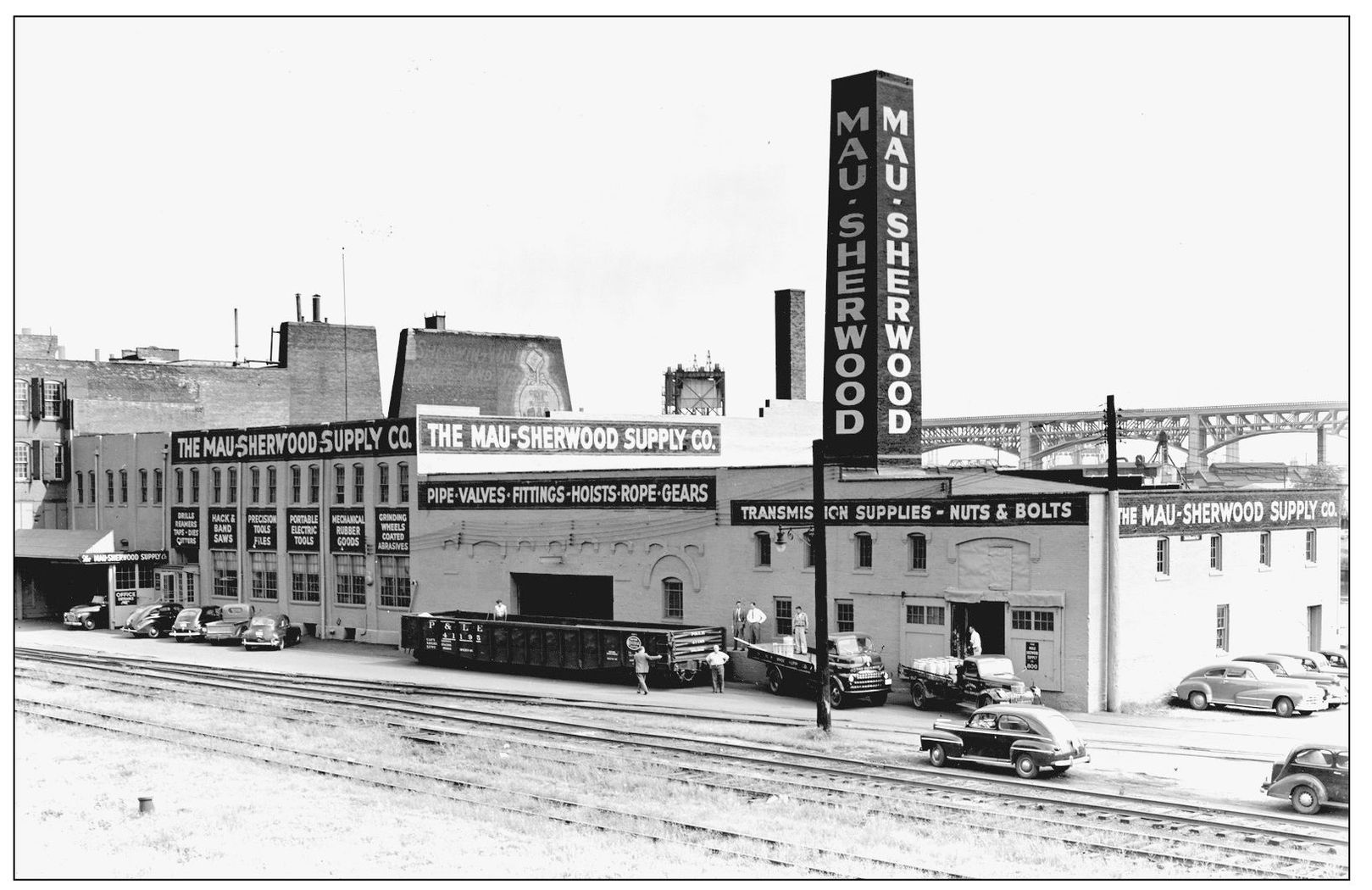

The Mau-Sherwood Supply Company could be counted on to provide items ranging from hack saws to rope. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

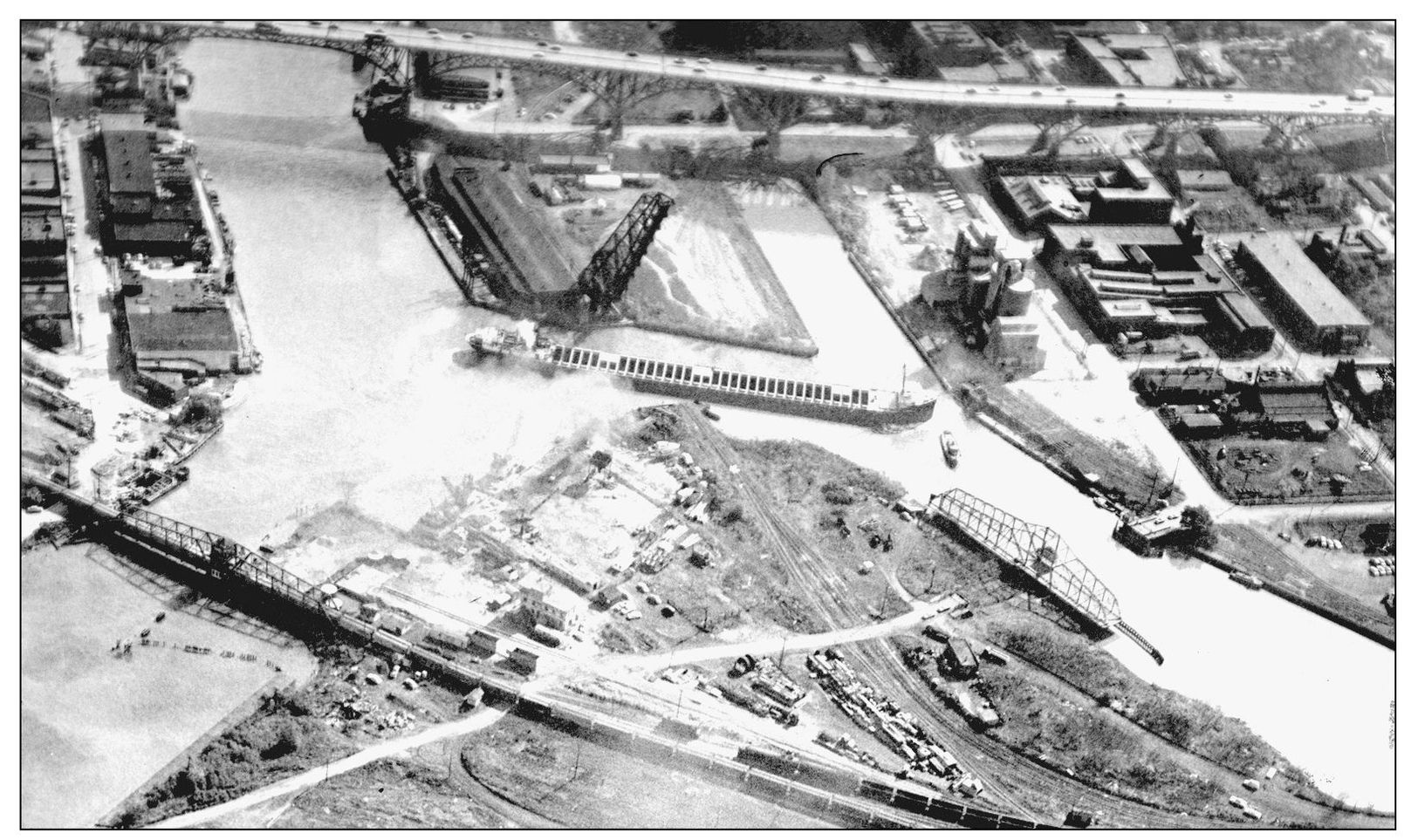

The bridges are at work while a freighter attempts to enter the old bed of the Cuyahoga. Spanning the mouth of the river is a swing bridge that served the New York Central and Pennsylvania Railroads. The raised trestle worked for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and the open swing bridge connected Willow Street to the west bank of the Flats. The Willow Street and New York Central and Pennsylvania Bridges would both be replaced. The Baltimore and Ohio trestle remains, but is locked in its raised position. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

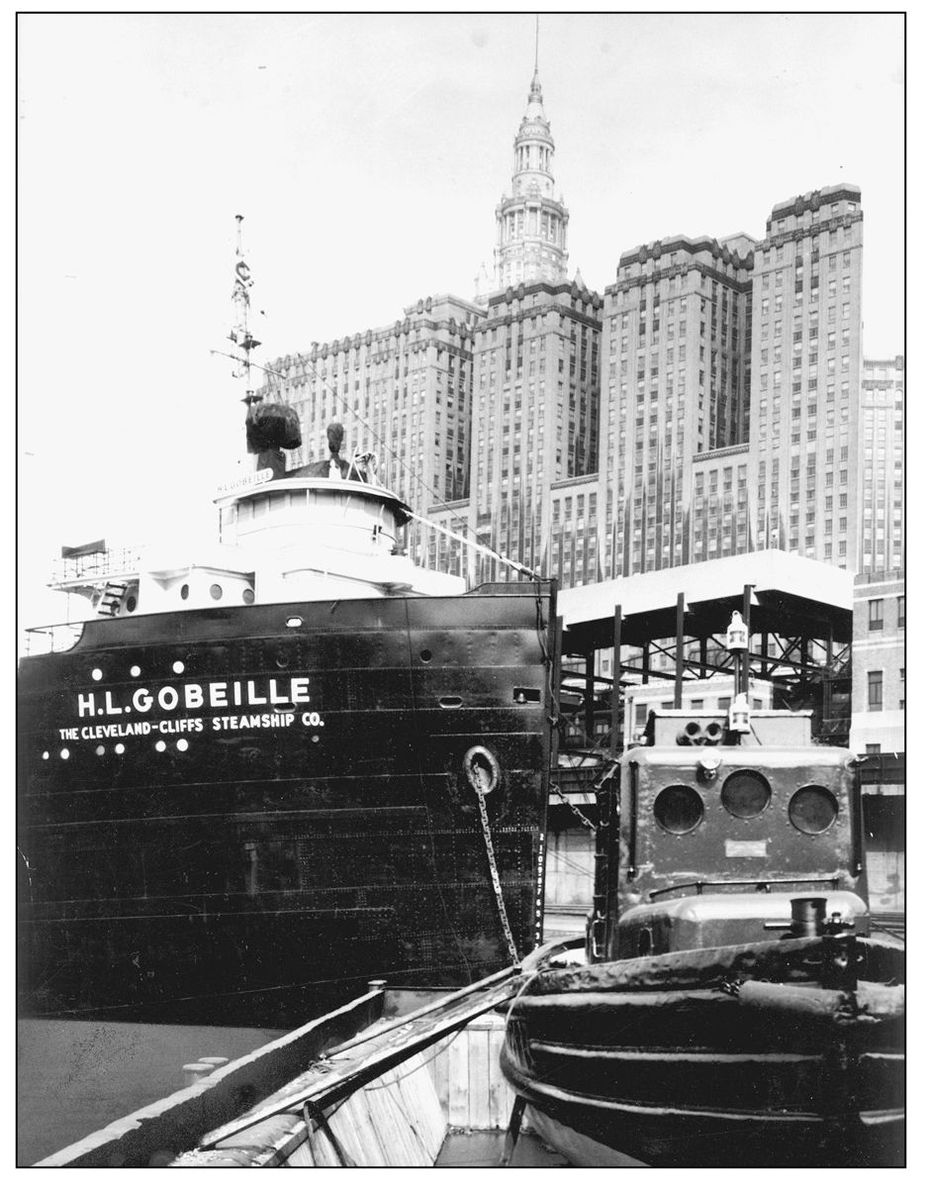

Some people involved in the maritime trade feel it is bad luck to rename a ship. Cleveland-Cliffs felt no such qualms, however, and would regularly rename its vessels. Among them were the H. L. Gobeille, which started its life as the William G. Mather. It was renamed the J. H. Sheadle (the second Cliffs boat to carry that moniker) in 1925 when Cliffs built a new Mather to serve as the fleet’s flagship. The 533-foot-long ship wound up as the Gobeille in 1955. Cliffs sold the boat in 1963 and it soldiered on under the name Nicolet until it was scrapped in 1996. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

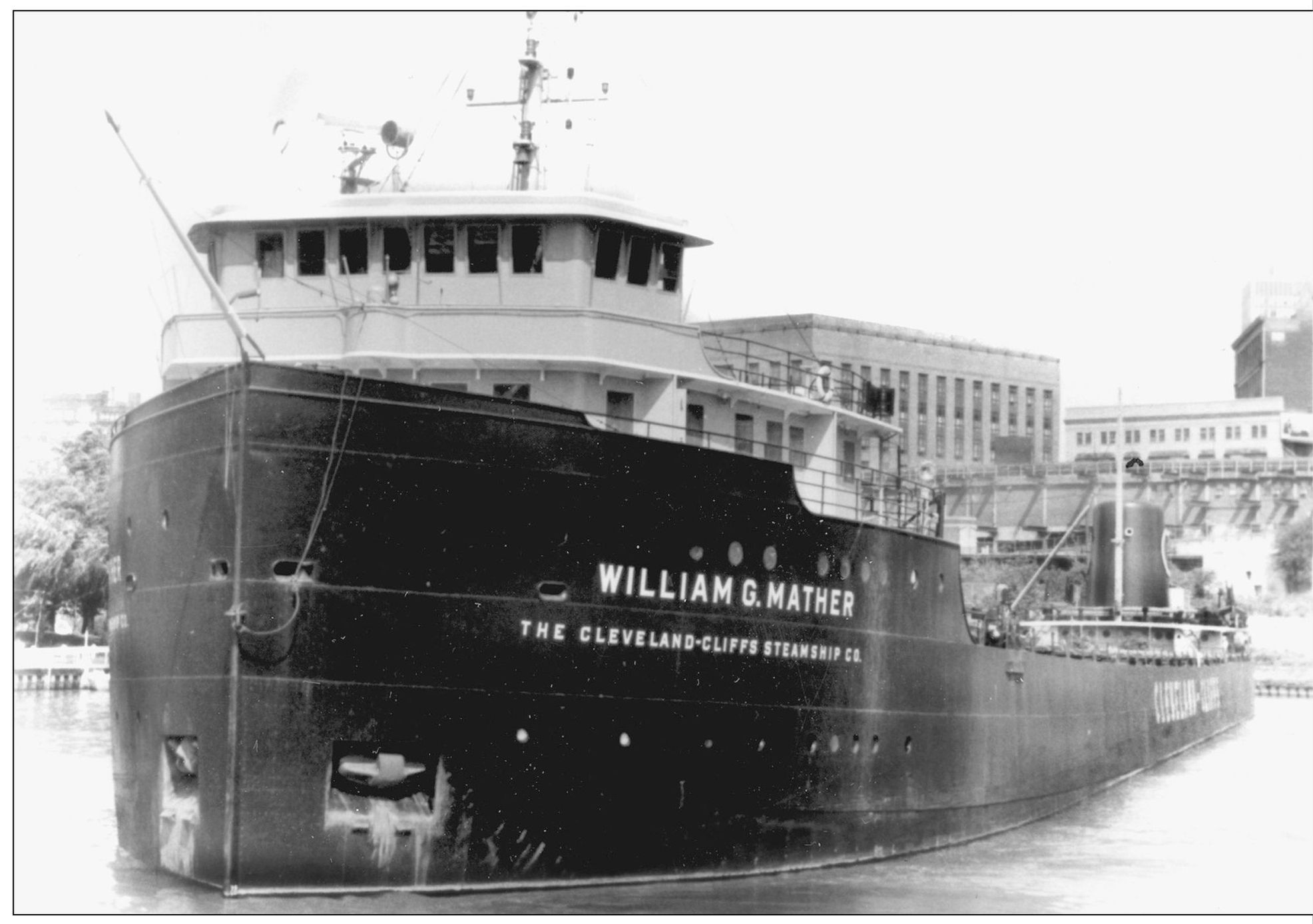

The second steamship to carry the name William G. Mather navigates Collision Bend. Unlike its predecessor, this Mather would keep its name throughout its entire career from 1925 until 1980. Although the ship lost its flagship status in 1952, it was still a viable member of the Cleveland-Cliffs fleet and was updated with new equipment, such as a new power plant (1954), a boiler automation computer, and a bow thruster (both in 1964). The Mather is now a museum ship moored behind the Great Lakes Science Center in Cleveland. (William G. Mather Collection—CSU Library Special Collections.)

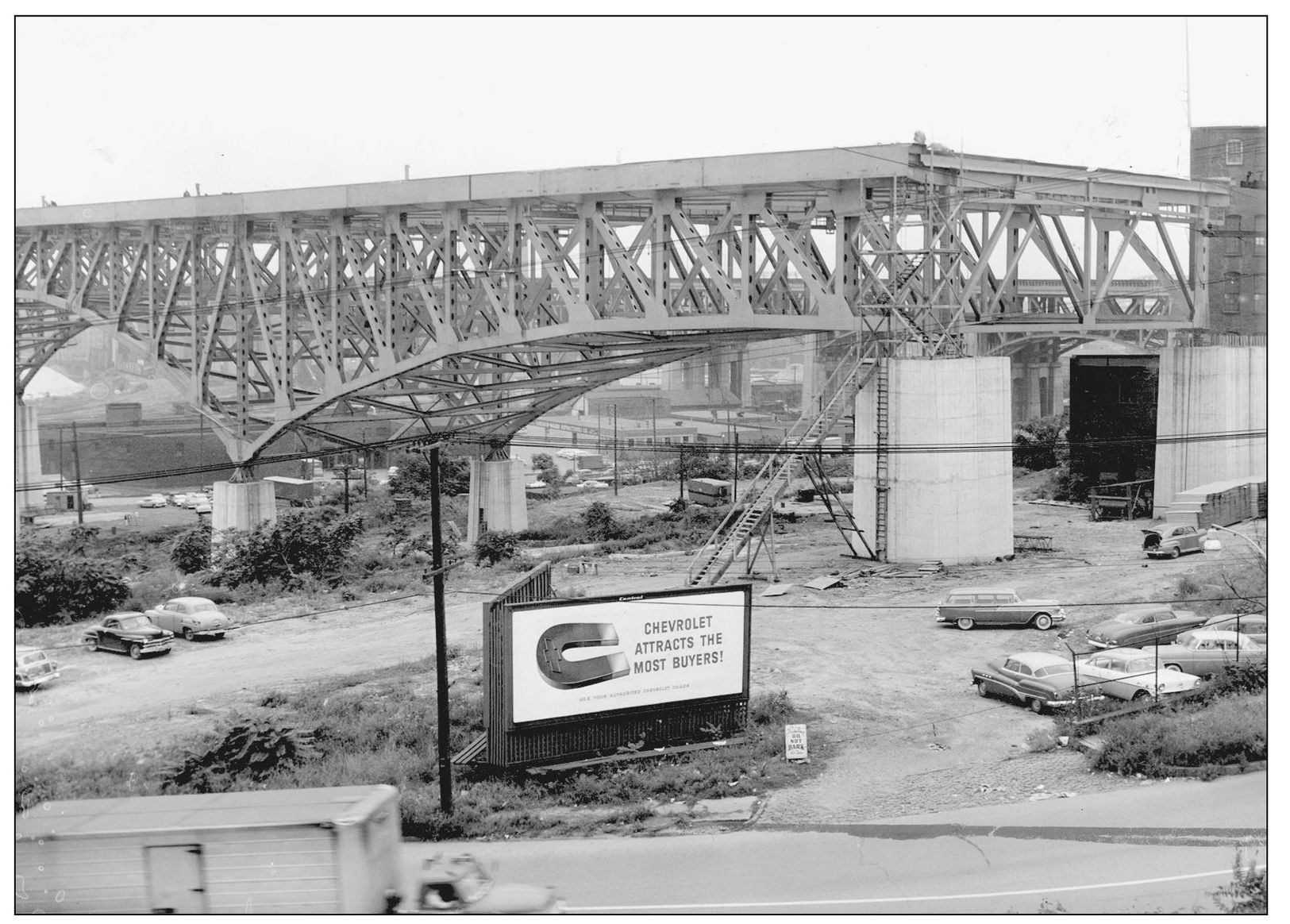

Completed in 1959, the Innerbelt Project would connect two major interstates (I-71 and I-90) to Cleveland’s downtown. This 1956 image is of the northern end of the Innerbelt Bridge over the Flats as it was being built. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

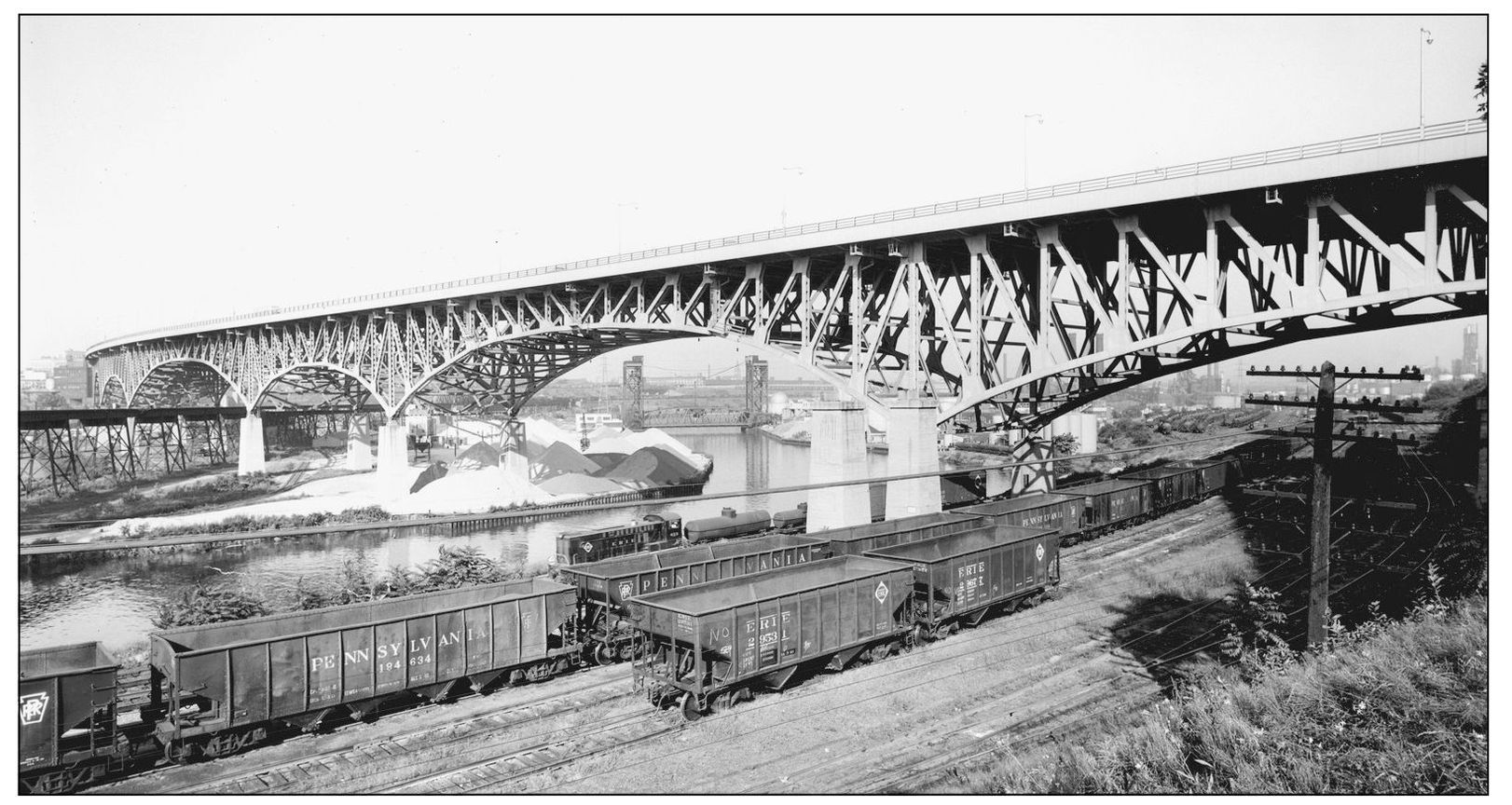

Pictured here is the southern portion of the recently finished Innerbelt Bridge. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

The hot rod set has long gathered in various parts of the Flats to not only display their machines, but to race them as well. A large group of car enthusiasts has gathered on a Sunday afternoon in this photograph taken in the spring of 1957. No matter how powerful these automobiles are, however, none can match the horsepower of a lake boat like SS Frontenac, seen with the Cleveland-Cliffs moniker on its hull. The Frontenac’s steam turbine engine could produce 5,000 horses. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

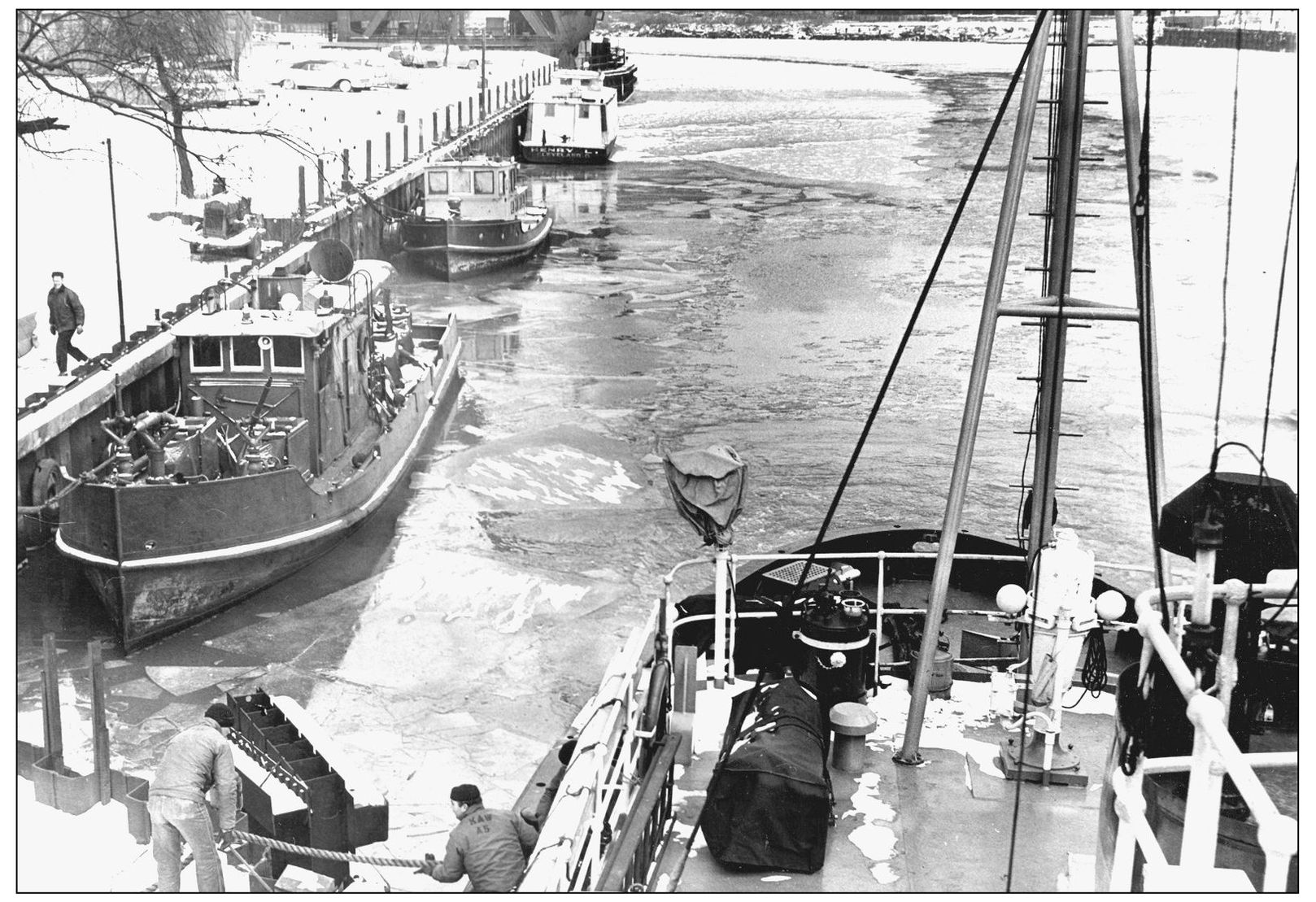

Crews fight to break apart ice on the Cuyahoga in February 1958. (Photograph by John Nash, Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

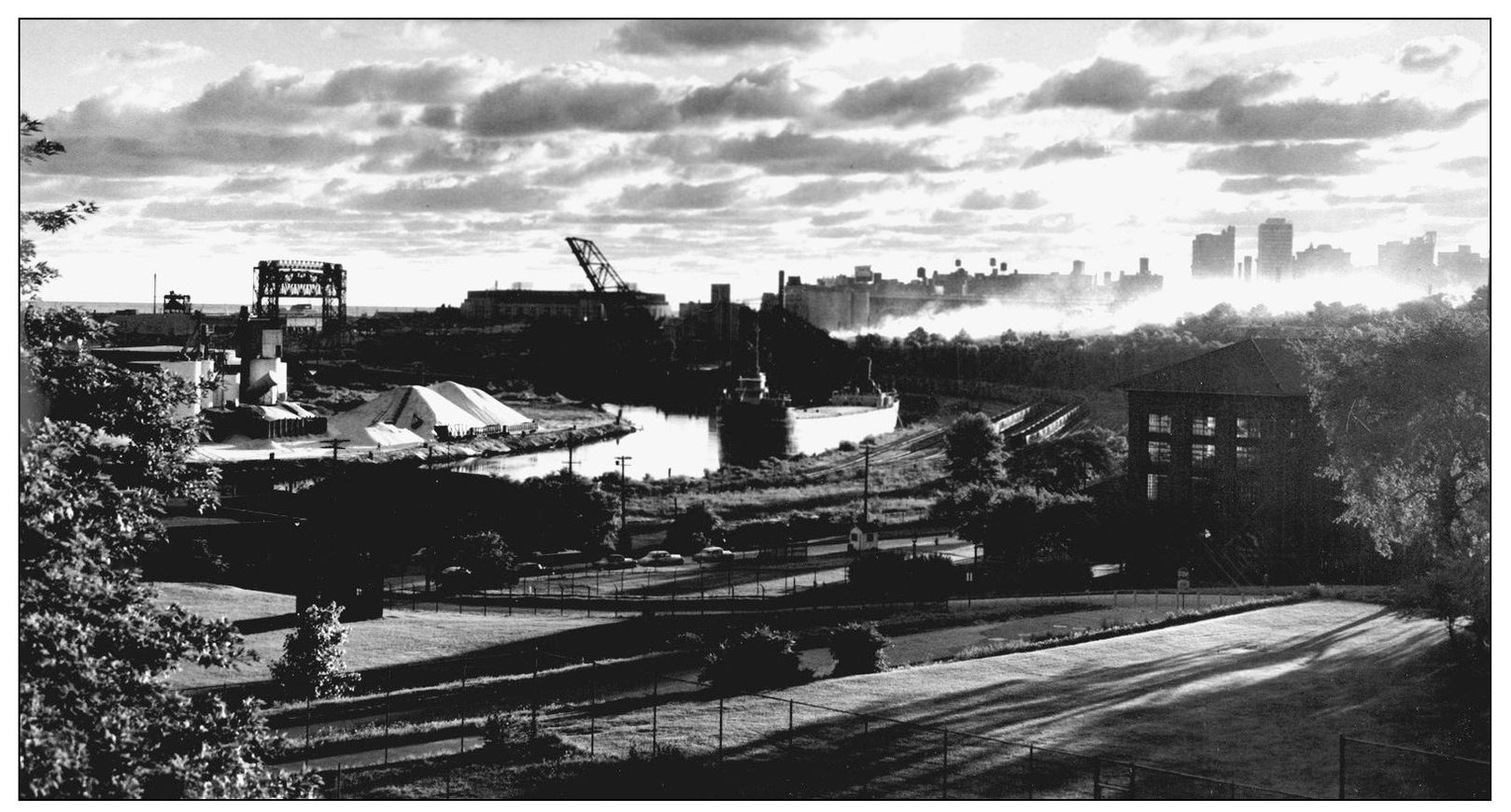

Clouds hang in the sky as the viewer looks east along the old bed of the Cuyahoga in this 1958 image. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

As the St. Lawrence Seaway Project neared its completion, the city of Cleveland attempted to improve its port facilities and navigation along the Cuyahoga. Taking a tour of the recently modified river are Cleveland’s customs collector Albina Cermark (left), Sen. John W. Bricker (center), and city port director W. J. Rogers. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

Straddling the Cuyahoga near the head of navigation is the Erie Railroad Bridge. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

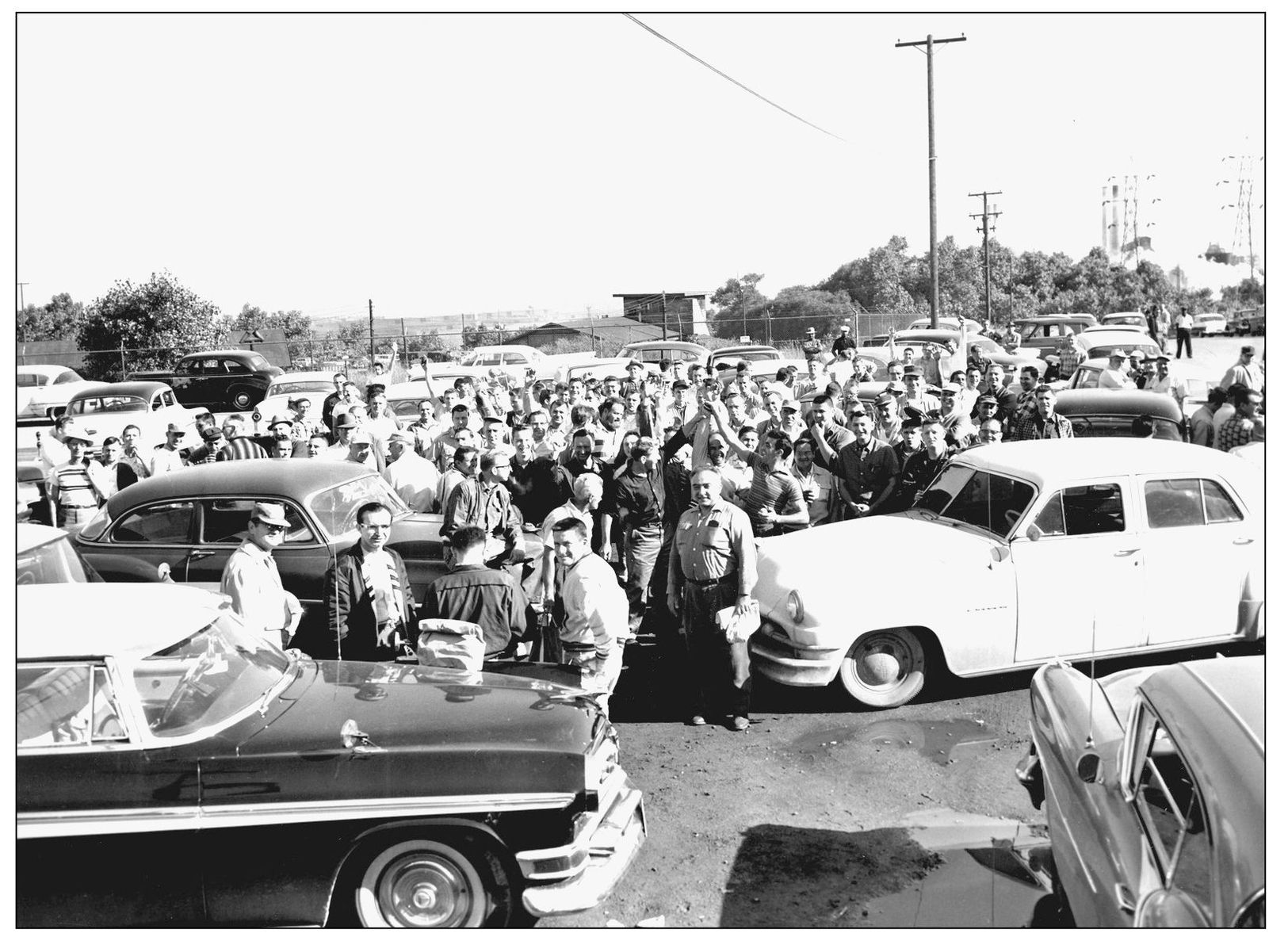

Workers from Republic Steel’s strip mill are on strike in the summer of 1959. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

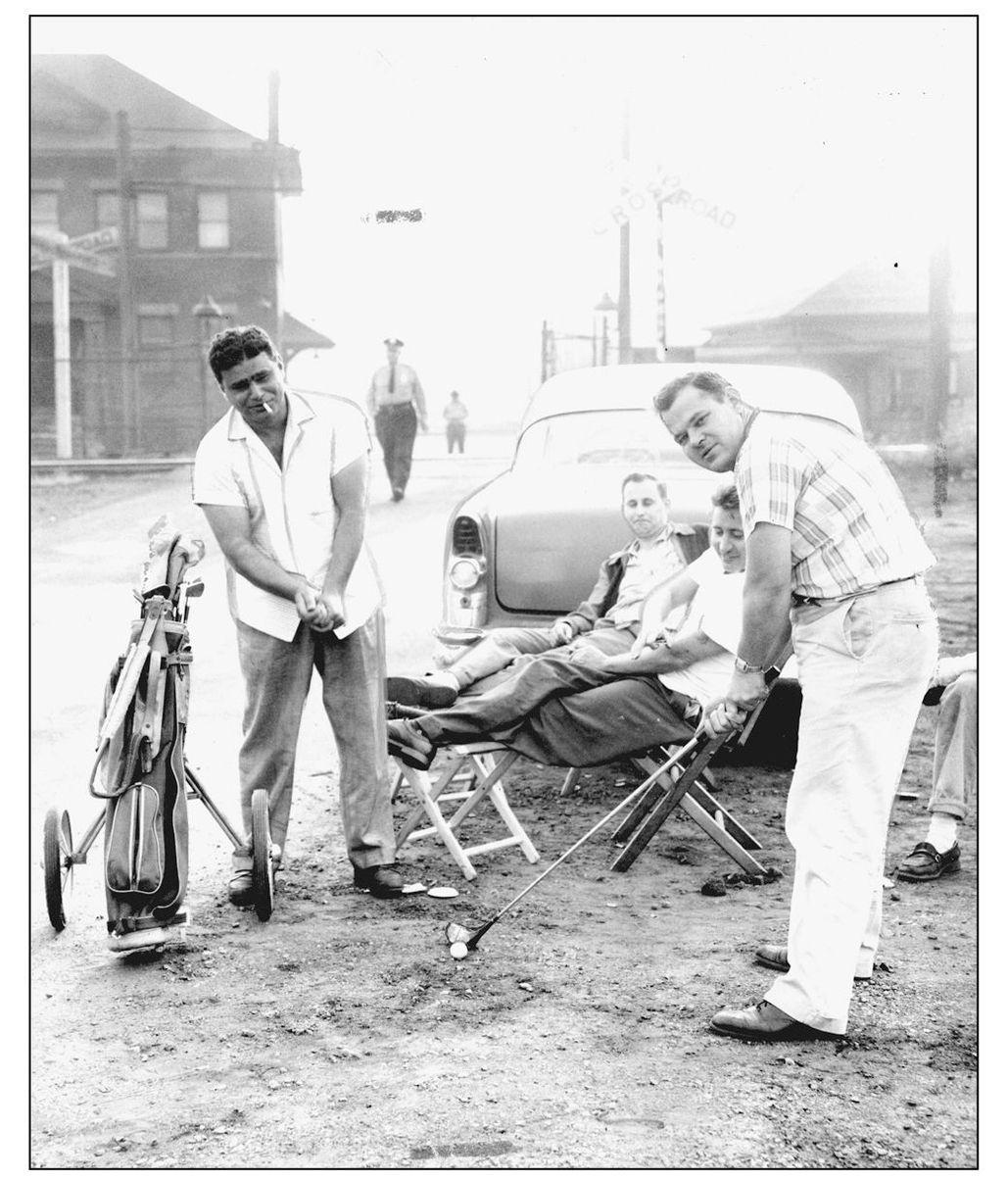

These men work on their golf swings while manning the picket line during the 1959 Republic Steel strike. (Photograph by Bernie Noble, Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)

Here is a winter lay-up along the old flow of the Cuyahoga. Note the unique boat in the inlet to the right of the image. That particular vessel is the Meteor, the last whaleback to sail the Great Lakes. (Cleveland Press Archives—CSU Library Special Collections.)