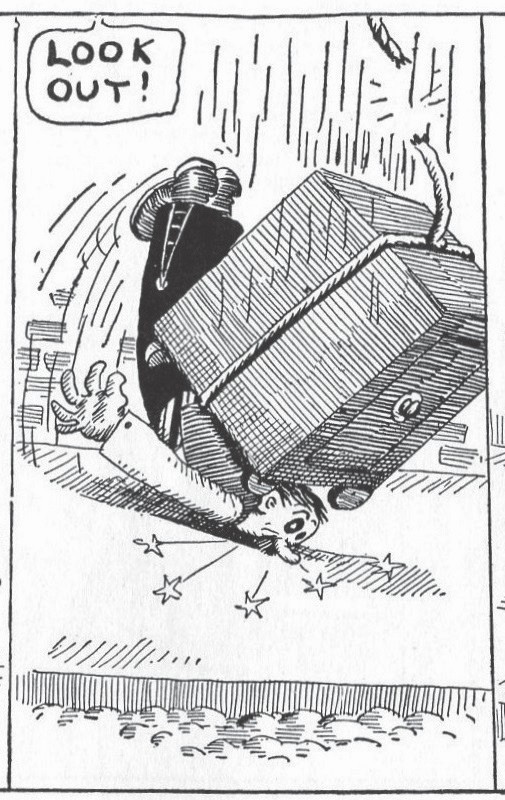

TO JUDGE BY old comics, safes became a standard feature of modern office buildings before elevators did, and so a common urban sight was a massive, heavy safe being hoisted to its roost by a pulley or crane. This was back in the age of recklessness, before seat belts, bicycle helmets, or flame-retardant pajamas, and sometimes the rope holding the safe would snap or slip. Old comics give the sense that that was an everyday occurrence, but it would need only to have happened once, on a busy Manhattan sidewalk, for cartoonists everywhere to register it as one more cartoonishly funny mishap they could inflict on their characters. And unlike the falling ANVILS in old Warner Bros. cartoons, the safes had a sensible reason to be way up there, suspended in midair, hundreds of feet overhead, and so offered a magnificent slapstick payoff without the suspension of disbelief required by Road Runner cartoons.

Fig. 134 From Mutt & Jeff, 1910

According to Don Martin, the sound of Superman failing to catch a falling safe filled with Kryptonite is “McPWAF!” As for the sound of an ordinary safe falling on ordinary mortals, that’s “FOOMP!” Basil Wolverton hears it differently: “Few people realize that the noise of a safe falling on a man is invariably ‘JWORCH!’” With so many safes dropping from the skies of Cartoonland, it’s lucky that in cartoons a direct hit by a falling safe is seldom fatal. It can even prove an inspiration: “A safe falls on the head of Professor Butts, and knocks out an idea,” says Rube Goldberg, in the era when he not only attributed his mad inventions to a mad inventor, but also specified the mind-clouding circumstances of each brainstorm. In this case—one of the few where the circumstances and the content of the brainstorm have any discernible connection—the idea is an elaborate fly-swatting machine.

I don’t have to look up my family tree, because I know that I’m the sap.

—FRED ALLEN

There are nineteen words in Yiddish that convey gradations of disparagement, from a mild, fluttery helplessness to a state of downright, irreconcilable brutishness. All of them can be usefully employed to pinpoint the kind of individuals I write about.

—S. J. PERELMAN, IN AN INTERVIEW FOR THE PARIS REVIEW

THE PROCESS OF writing this guide has gotten me thinking hard about taxonomies of human folly. Humorists have always been drawn to such taxonomies, with stage comedy in particular relying heavily on stock characters like the senex, meretrix, and parasitus of Roman comedy; the Harlequin, Pantaloon, and Pulcinella of commedia dell’arte; or the fops, rakes, and wits of Restoration comedy. And of course this reliance on comedic stereotypes continues up to our time in Hollywood, though now that we’re all such wised-up postmodern sophisticates, those stereotypes are sometimes openly subverted or lampooned, as in Not Another Teen Comedy (2001), whose characters are identified by their clichéd roles: the Token Black Guy, the Best Friend, the Pretty Ugly Girl.

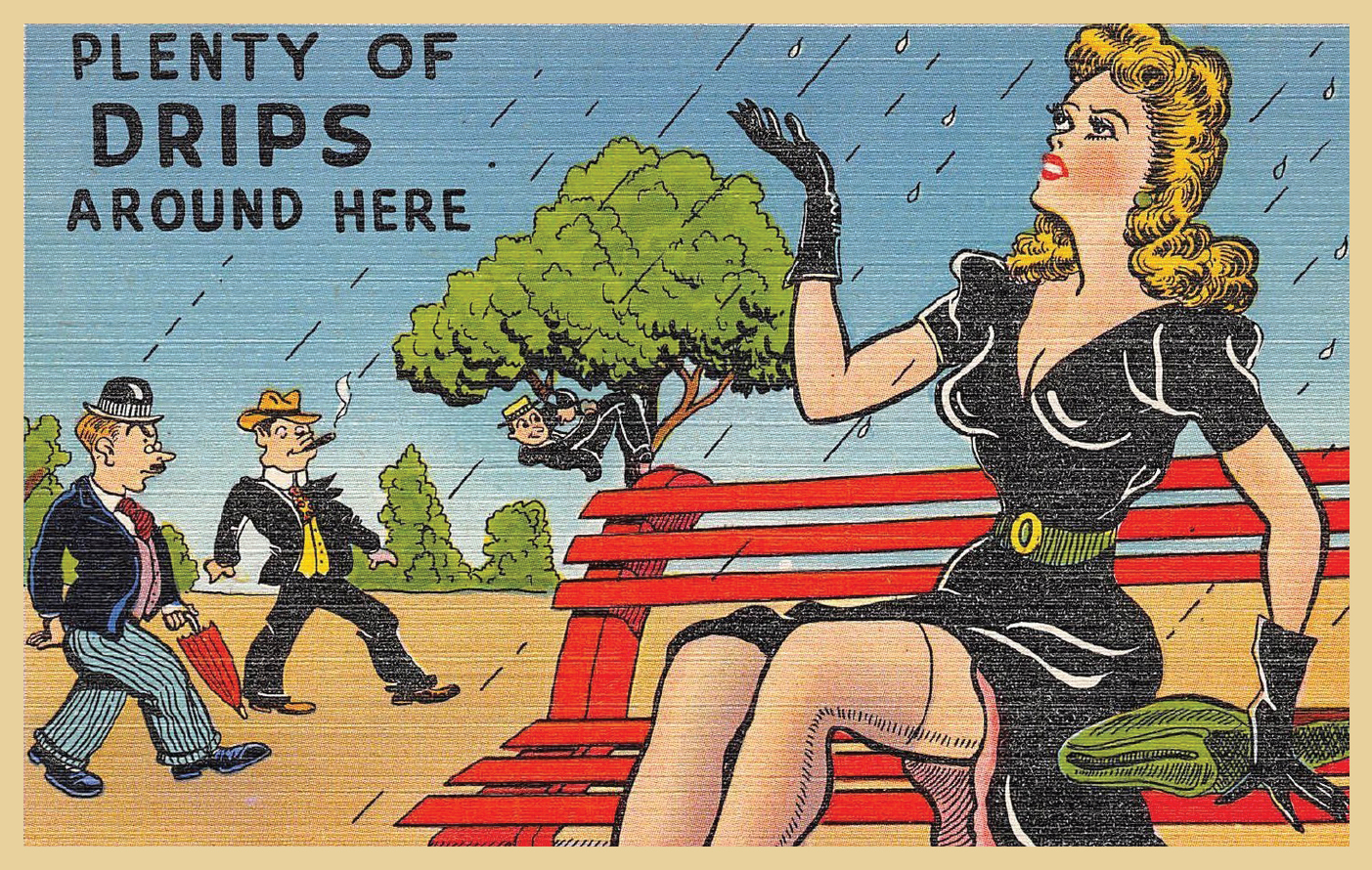

Fig. 135 Saps = drips. See also PRETTY GIRLS.

Since I want this book to be in some sense comprehensive without being dauntingly long, I’ve thought a lot about the stock characters of American humor. Just how many are there? How many different types must I describe in order to do justice to the human comedy as it appeared to our grandfathers? Which are dispensable? Clearly there must be BLOWHARDS, TIGHTWADS, GOLD DIGGERS, MOTHERS-IN-LAW—but must we also have separate entries for Dips, Clucks, Drips, and Saps? Can the obsolescence of those terms be taken as proof that they were redundant all along—that they never represented distinctive patterns of human behavior meriting names of their own?

Linguists assure us that words drop out of the language only when no longer needed, but that isn’t always true. There’s no one-word synonym for yonder, and we have as much need as ever to say what it says so tidily (“way over there”), but the word is vanishing, as are hither and thither. So we shouldn’t assume, from that fact that people no longer refer to one another as “saps,” that saps are extinct. Saps are as plentiful as ever, in this observer’s opinion, but old insults are dying off: the kudzu-like spread of a few invasive species, like asshole and loser, has crowded out many more-delicate epithets, leading to a catastrophic loss of logodiversity.

What or who exactly is or was a sap? Of the few surviving terms, loser probably comes closest, but not close enough. All it takes to qualify as a loser is bad luck, but to be a sap you need a bad attitude, too. (Job in the Old Testament was a loser, not a sap.) A sap is a loser who loses through stupidity, so maybe chump or sucker are closer to the mark, except that both reflect a heartless and almost eugenic contempt for the bad luck of a low IQ, just as loser reflects a heartless contempt for bad luck tout court. A sap is a loser who loses due to wrongheadedness; his behavior (and the term was pretty much confined to men) represents a sort of elective stupidity, rather than expressing a genetic limitation.

Whatever they were, saps were everywhere in the Jazz Age. They were as common as FLAPPERS in that era, to judge by the movies the era produced: The Fighting Sap (1924), Two Gun Sap (1925), The Sap (1926), The Perfect Sap (1927), The Sap (1929), Singing Sap (1930), The Sap from Syracuse (1930). Of course, no flapper worthy of the name would give a sap the time of day.

I’ve knuckles of pigs

And tails of oxen,

And if the prospect should leave you glum,

Cheer up, for the Wurst

Is yet to come.

—PHYLLIS MCGINLEY, “CHANT OF THE OPTIMISTIC BUTCHER,” 1945

IN “DOG FACTORY” (1904), a short film by Thomas Edison, we glimpse an invention that Edison never perfected: a Dog Transformator. This amazing machine, basically a box with a hopper on top and a door in the side, can almost instantaneously turn a live dog into links of sausage. Draped on pegs on the wall behind the machine are coils of sausage labeled by breed—Poodle, Spaniel, Pointer, Setter, and so on. But this factory is more than just a butcher shop; it’s a pet store, too, because the transformator also works in reverse. If you want a dachshund, you point to the corresponding sausage, which the clerk drops into the machine, and out scampers a living wiener dog. If the customer changes her mind, as lady shoppers proverbially will, back into the hopper goes the dachshund, returning to its low-maintenance sausage state. Apparently I’m not the first pet owner to daydream about putting my beloved pets in suspended animation whenever I need a vacation from them.

Except perhaps for wiener dogs, the similarity between true dogs and hot dogs is slight at best. But the fact that we refer to one unaccountably popular sausage as a “hot dog” has given rise to a lot of verbal and visual punning. A recurring sight gag in Felix the Cat cartoons involved hot dogs behaving like normal dogs. When Felix wants to go to Alaska, he harnesses six hot dogs to a sled.

But dogs are not what hot dogs are most often compared to. Freud saw phallic symbols in places where most of us see nothing of the sort, but sometimes they’re hard not to see. Unless you’re so pure-minded that you could browse in a dildo emporium without seeing a phallic symbol, you’ll agree that the resemblance of hot dogs and sausages to PENISES exists not just in the dirty minds of Freudians, but in the dirty mind of popular culture. There are borderline cases—we may never know how much of a smirk we’re entitled to during the Patty Duke theme song (“But Patty goes for rock and roll, / A hot dog makes her lose control”)—but sometimes it takes an act of willful piety to miss it. Foot-long wienies are funny because men are obsessed about the length of their own wienies. As for the endless hot dog invented by Pansy Yokum in a 1955 episode of Li’l Abner (“As the customer chomps one end o’ th’ endless hot dog,” reads a hand-lettered sign in Pansy’s hotdog stand, “the machine is manufacturin’ t’other end—and since this machine don’t never stop, the hot dog is endless—as any fool kin plainly see!!”)—I don’t know where to begin.

When Irvin S. Cobb made his pronouncements on the relative funniness of various foods, he asserted that “a sausage is positively uproarious.” A good example of an uproarious sausage occurs in Some Like It Hot, when thirteen young women join “Daphne” (a cross-dressing Jack Lemmon) in his sleeper berth for drinks and innocent horseplay. Many of the guests bring refreshments of one kind or another—cheese and crackers, Southern Comfort, peanut butter—but the salami brandished by one of the lady musicians is indisputably a dick joke. After all, what makes the scene so memorable is that one of the fourteen girls is actually a boy. The salami is a metaphor (though so crudely obvious it barely counts as one) for the secret subtext of the scene—a secret that Jack Lemmon had been preparing to expose (so to speak) to Marilyn Monroe when a dozen party crashers ruined his tête-à-tête, and a secret all too likely to expose itself when a sexually excited man is crammed into a tiny sleeper berth with thirteen grabby gals. That’s the real reason Jack pulls the emergency brake.

Some Like It Hot was notoriously racy for its time, its country, and its medium—but that’s not saying much. Off camera, offstage, off the air, and off the record, ordinary Americans were telling rawer jokes than Hollywood could stomach. My favorite dirty sausage joke is one that Gershon Legman heard in New York City in 1936 and classified, in his flabbergasting typology of dirty jokes, as one about “Traces of the Other Man”:

The day before marrying for money, a girl has one last fling with the man she really loves. He has no condom and they use the scooped-out skin of a bologna, which slips in during intercourse and cannot be retrieved. On her wedding night it comes out on her husband’s penis. When he asks what it is, she says it is her maidenhead. “Well that’s the first one I ever saw with a government stamp on it!”

When they aren’t reminding us of penises, sausages may remind us of turds, a resemblance Mad magazine’s Al Jaffee exploited so effectively in a 1975 feature called “Mad Solutions to Big-City Doggie-Do Problems.” Jaffee’s own doggie-do problem as a cartoonist was how to illustrate his fanciful solutions—such as coating each dog turd with quick-drying acrylic—without picturing actual turds. (Even Don Martin shrank from drawing recognizable turds, though he did give us some good turd humor, usually involving the telltale sound effect “GLITCH!”). Jaffee drew chubby little links of sausage instead.

The sausage/stool resemblance may explain why a string of sausages is the single most common form of meat for a dog to steal in old cartoons, though there are all sorts of other funny and delicious things in butcher stops, like HAMS. The angry butcher shaking his fist at the mutt reminds us that dogs are thieves who eat what isn’t theirs. The string of little sausage links reminds us that the other end of the implacable canine digestive tract is equally lawless.

Or maybe it’s just that anything is funnier when you involve a sausage. Steve Allen, in a stunt prefiguring by several decades those of David Letterman, once rushed out of his TV studio dressed as a policeman and holding a big salami. He put the salami in the back of a cab and told the driver: “Get this to Grand Central Station as quick as you can!” The driver obeyed.

No McTavish / Was ever lavish.

—OGDEN NASH, “GENEALOGICAL REFLECTION”

IN 1935, THE Exhibit Supply Company of Chicago published a series of humorous photographic postcards called “Your Future Husband and Children.” Strictly speaking, these were arcade cards—the size of postcards, but printed on heavier card stock, with blank backs (because they weren’t intended to be sent, and some of the racier series would have been unsendable), and sold from vending machines in penny arcades. The “Future Husband” series, like several similar series of arcade cards from that era, was a precursor of Mystery Date, that 1960s board game in which little girls were taught a typology of possible beaux, some more desirable than others. Because the arcade cards were sold to bigger girls, they acknowledged more of the variety and complexity of prospective mates. You could end up with a dashing aviator, or a rich but tyrannical geezer, or a dumpy but good-natured gas station attendant, or a fast-talking, skirt-chasing salesman, or any of a dozen or so other destinies.

One of the least desirable husbands was the Scotsman, pictured in a tam-o’-shanter and full lowlands regalia, and smiling drunkenly above this caption:

YOUR FUTURE HUSBAND will be a tight Scotchman, in fact he will be tight most of the time. Every time he opens his pocketbook, the moths fly out. He will be so cheap that he will squeak, and he will pinch the pennies until the Indians howl. He will love his grog and his eight little Scotties [the future children, also pictured], who will show you a good time by all playing bagpipes at the same time.

Aside from the howling Indians—clearly an old joke by 1935, since Indian-head pennies were discontinued in 1909—the only witty thing about that clumsy caption, with its awkward repetitions of “time” (was the writer a clock-watcher paid by the hour?), is the punning use of “tight.” IRISHMEN are also proverbially drinky, and Jews proverbially stingy, but only Scotsmen unite these two traits, which otherwise are as immiscible as oil and water.

In the popular imagination, Scotsmen even are stingier than they are drinky. “Genealogical Reflection” is the second poem of Nash’s first collection, and shows that in 1931, it was still okay to imply that the Scottish have an innate predisposition to miserliness. You won’t find a chapter of Darky Jokes in Louis Untermeyer’s Treasury of Laughter48 (1943), but you’ll find a chapter of jokes about Scotsmen and their stinginess. In one joke, MacDonald reminds his wife to make their son take off his glasses whenever the lad isn’t looking through them. In another, MacPherson buys a single spur, reasoning that if one side of his horse goes, the other will too. In a third, Sandy grieves that his wife has died before she had time to finish the pills the doctor made her buy.

Because of their proverbial frugality, Scotsmen were a natural choice for toy banks. One made in Germany in the 1930s was designed with a protruding tongue that withdrew when a coin was placed on it: the Scotsman swallowed the coin. Another old tin bank portrayed the Scotsman as drunk as well as miserly, with a head that bobbed when coins were inserted.

“The Irish gave the bagpipes to the Scots as a joke,” wrote Oliver Herford about a century ago, “but the Scots haven’t got the joke yet.” The Scottish are supposed to be humorless, too, as are TIGHTWADS in general. No doubt this is unfair to Scots, but is it fair to tightwads? Is pathological solemnity itself a form of stinginess? That would make humor a form of generosity and not, as Freud contended, a form of parsimony: “The pleasure in the comic [arises] from an economy in expenditure of ideation . . . and the pleasure of humor from an economy of expenditure of feeling.” In other words, we laugh as a way of expending less thought and feeling on events that otherwise would be prohibitively thought-provoking and upsetting. So it makes perfect sense that a tightwad like Jack Benny would also be—where humor is concerned—a spendthrift. It makes less sense, if you swear by Freud, that certain nationalities (the Dutch are another) should be proverbial for both lack of humor and lack of generosity. But economic metaphors are only metaphors.

THOUGH MANY MISTAKE him for nothing but a lowly bus driver, Ralph Kramden is also the treasurer of the International Order of Loyal Raccoons, the lodge to which his buddy Norton also belongs (just as, on that shameless Honeymooners rip-off The Flintstones, Fred and Barney belong to the Loyal Order of Water Buffalo). All the hubbub on the show about lodge activities was one of its more inspired features, perfectly summing up Ralph’s pitiable need to feel important.

The producers of The Honeymooners weren’t the first humorists to find such lodges funny, or to see the poignancy of their appeal to losers in nowhere jobs and nowhere lives—and indeed to any man whose sense of self-importance far outstrips his importance in the eyes of his spouse, employer, and neighbors. One such figure was BLOWHARD par excellence Major Hoople from Our Boarding House, the great one-panel newspaper cartoon from the 1920s and ’30s. In a 1927 installment, Hoople explains the appeal of the lodge: “Hmf! To a nettlehead, this costume would provoke coarse guffaws and rude gibes, but in my lodge, it is the symbol of dignity and power. I . . . am the Exalted Prince of the Mystic Ruby.” (“What do they call th’ guy with th’ next reddest nose?” asks one of the wisecracking boarders who function as a sort of pitiless Greek chorus puncturing the major’s hubris.)

Laurel and Hardy’s best movie, Sons of the Desert (1933), is the locus classicus for all subsequent humor about lodges. It involves a plot that became de rigueur in any radio or television sitcom with lodge-related episodes: husbands want to go to big lodge convention in big wicked city (usually Chicago); wives forbid them, rightly or wrongly suspecting that convention is pretext for all kinds of male misbehavior; husbands use deceit to go anyhow; wives get wind of deceit. Both Stan and Ollie play severely HENPECKED HUSBANDS whose wives routinely throw crockery to enforce decrees (at one point, Ollie wears a pot on his head as a helmet). Comedy husbands who belong to secret societies are almost always henpecked, because that’s the obvious way to deflate the adolescent male fantasy of power and importance that lodges cater to.

It was a fantasy that appealed to many men, and to many scriptwriters who made light of male grandiosity at its most endearingly silly. It goes without saying that self-aggrandizing buffoons like Fibber McGee and Chester A. Riley (star of The Life of Riley) belonged to lodges, but who’d have guessed that Andy Griffith would, or Gomez Addams? On Amos ’n’ Andy, both the title characters belonged to the Mystic Knights of the Sea. On the immensely popular radio show Vic and Sade (1932–46), Victor Gook was by day a mild-mannered accountant for the Consolidated Kitchenware Company, but when the sun went down Vic had a secret life as Exalted Big Dipper of the Drowsy Venus Chapter of the Sacred Stars of the Milky Way—and whole episodes were devoted to his lodge regalia (“boots, sword, tunic, plume hat, robe”), lodge outings, lodge speeches, and lodge library.

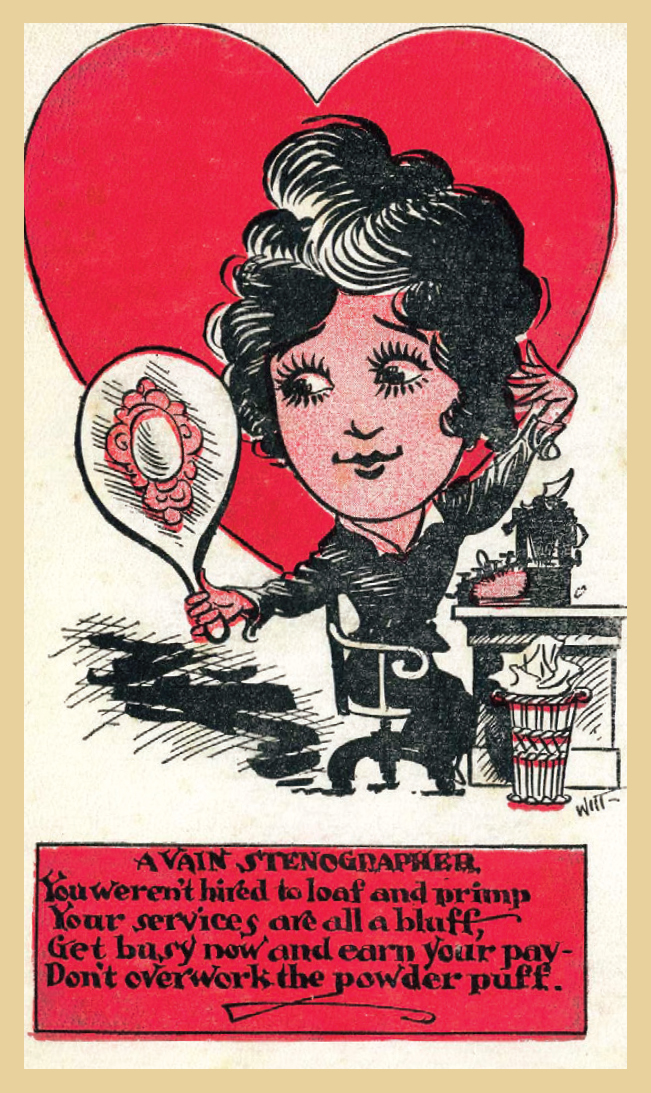

This Month’s Drawing Account: The Boss drew the cork, the stenog drew the curtains and the office boy drew his conclusions!

—CAPTAIN BILLY’S WHIZ BANG, c. 1930

When the struggling stenographer quits struggling, she discovers she doesn’t have to be a stenographer.

—HENNY YOUNGMAN

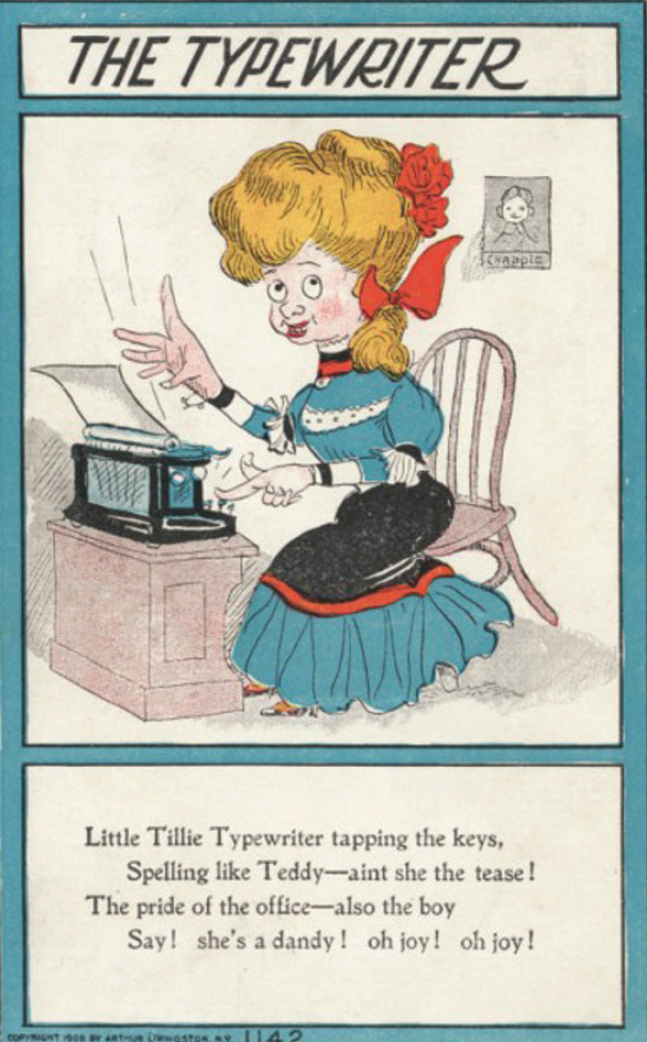

THE TYPEWRITER AS we know it, or knew it, was developed in the 1860s—Mark Twain, an early adopter, used one for Life on the Mississippi—and almost at once a new stock character joined the Central Casting department of our culture’s collective consciousness: the Typewriter, named for the machine she operated. In the early days, in fact, typewriter was more likely to mean the operator than the machine, but its very ambiguity was exploited by humorists. In a cartoon dating from around 1910, a young male job applicant stands before an elderly boss and his cute young typist. “I see you can write shorthand,” says the boss, “but are you familiar with the typewriter?” “No,” replies the applicant, staring at the typist, “but I can soon manage that.”

As the cartoon implies, typing wasn’t thought of as strictly women’s work. When Henry James bought a typewriting machine in 1897, his first typist was male. In 1901, James replaced the man with a woman, for reasons that suggest why the corporate world was soon to kick the men out of the typing pool: “I can get a highly competent little woman for half. It’s simply that I don’t want to put so much more money into dictating than I need.”

There was of course another reason: unlike Henry James, most of the men employing stenographers and typists were attracted to the opposite sex, and even happily married bosses preferred to share their corner offices with pretty young women rather than surly young men. As the phrase implies, “taking dictation” demands submissiveness, a trait that our culture encouraged in women in a way it never did in men.

By the 1930s, typist had become the standard term for the operator, though as recently as 1953, typewriter could still mean the person and not the machine, to judge by a risqué joke published that year: “Confucius say, ‘Typewriter not permanent until screwed on desk.’” By then, of course, typists were usually female, as stenographers had been for several decades—had been, indeed, ever since that term emerged. (The word derives from stenos, Greek for “narrow” or “close”—stenogamous insects are ones requiring no nuptial flight to mate—and means a writer of shorthand.)

And it’s easy to pinpoint the nation’s fascination with stenographers so designated. The Internet Movie Database lists fourteen films with stenographer in the title, and twelve of them date from between 1910 and 1916: The Stenographer’s Friend, Mutt and Jeff and the Lady Stenographer, Oh! You Stenographer, The New Stenographer, Stenographer Wanted, The Ranch Stenographer, Dad’s Stenographer, The Substitute Stenographer, The Stenographer, The New Stenographer (again), Mr. Jack Hires a Stenographer, and The Good Stenographer. Though the Mutt and Jeff title might suggest otherwise, stenographers were almost always women, at least in popular culture; that was of course the secret of their fascination. Not that there’s anything especially female about the work; until the twentieth century, in fact, scribes were usually male, like Bartleby the Scrivener, the unwilling office drudge in Melville’s 1853 novella.

The word and the job were still around in the 1920s, but so taken for granted that the title was often abbreviated, as in His New Steno, a film from 1928. Somebody’s Stenog, an A. E. Hayward comic strip that debuted in 1924, starred a ditzy blonde named Cam O’Flage, and ran until 1940, when its increasingly archaic title may have contributed to its demise. (Public Stenographer, the only other movie title turned up by my IMDB search, came out in 1934.)

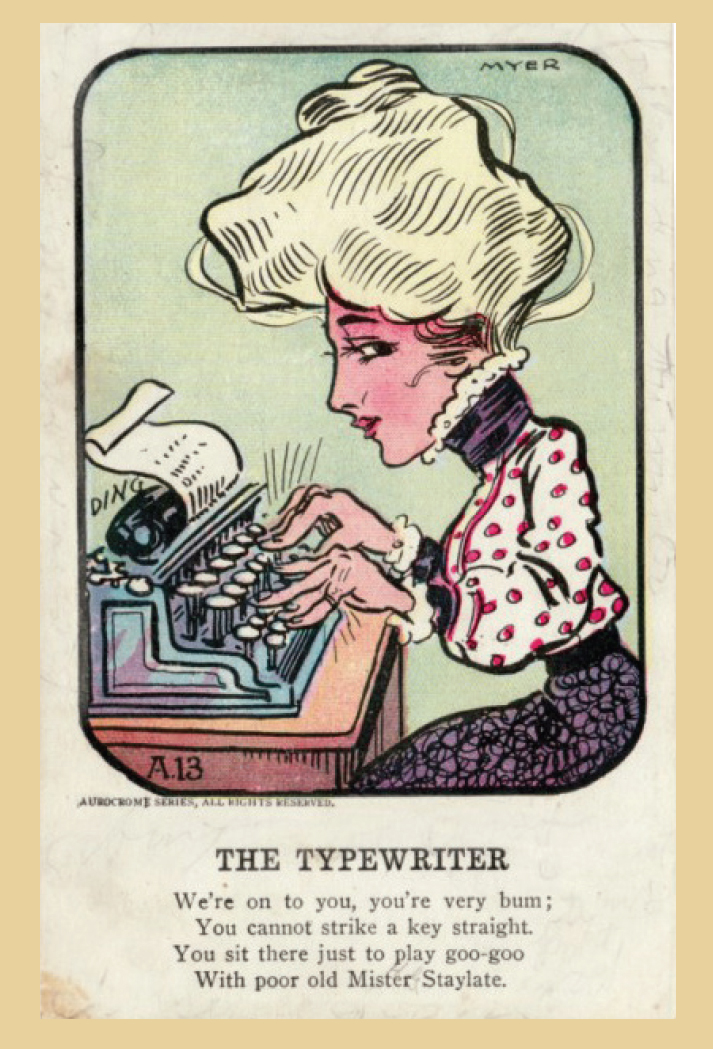

Fig. 136

Fig. 137

Fig. 138

Fig. 139

In the American workplace, secretary began as a pretentious synonym for typist or stenographer (itself originally a pretentious euphemism), and was subjected to the sort of ridicule later heaped on other occupational grandiloquisms like mortician, custodian, and sanitary engineer. Whatever you call her, the stereotype of the inept, airheaded office worker who owes her job to sex appeal has been around for more than a century now. An insult postcard dating from 1907 showed a pretty BLONDE typing above this caption:

THE TYPEWRITER

We’re on to you, you’re very bum;

You cannot strike a key straight;

You sit there just to play goo-goo

With poor old Mister Staylate.

It was a common joke in lowbrow humor magazines like Captain Billy’s Whiz Bang, which in the 1920s and ’30s entertained those who found The New Yorker’s sense of humor too uppity. “The faster a stenographer is, the more likely she is to stay in one place,” observed Captain Billy in 1927. Six years later, lamenting the high unemployment, he complained that “jobs have been scarcer than a stenographer on the Virgin Islands.” Decades later—long after anyone still described herself as a stenographer—Diana Vreeland wrote of Coco Chanel, “Her first customers were princesses and duchesses and she dressed them like secretaries and stenographers.” With so many slurs against the profession, it’s no wonder stenographers decided to stop calling themselves that.

You want to fall in love with a shoe, go ahead.

A shoe can’t love you back, but, on the other hand, a shoe can’t hurt you too deeply either.

And there are so many nice-looking shoes.

—ALLAN SHERMAN

LESSON #6 IN the Pocket Cartooning Course (1943) was devoted to Shoes, either because cartoonists as a class are shoe fetishists, or because shoes are funny. Shoes are funny. Maxwell Smart’s shoe phone appears in the very first scene of the pilot episode of Get Smart (1965), ringing in Symphony Hall during a stuffy Beethoven concert—as real-world cell phones wouldn’t do for several decades. Shoes are a key ingredient in Kickapoo Joy Juice, the almost lethally intoxicating beverage brewed by two denizens of Li’l Abner’s Dogpatch.

And clearly shoes are also fun to draw. In Rube Goldberg’s elaborate machines, the single most common component, not counting standard machine parts like pulleys and gears, is a heavy-looking shoe or boot, usually used either to kick or to step on the next item in the unlikely chain of causation. In Goldberg’s orange-juicing machine, a diving boot stomps on the head of an octopus who then mistakes the orange for the diver’s own head and squeezes it in anger. Goldberg’s portable fan, on the other hand, involves six shoes mounted on a sort of paddle wheel in such a way that when the wheel turns, the shoes kick a little bear in the rump repeatedly, though several more steps intervene between the maltreated bear and the waving fan.

Old shoes as well as TIN CANS were sometimes tied to the back bumper of the newlyweds’ getaway car. Tin cans and old shoes: a very common pairing in old comics. Goats eat shoes when no cans are available. Hapless cartoon fishermen tend to snag one or the other; indeed, the old shoe (or boot) is the single most common non-piscine object for a cartoon fisherman to catch, and the tin can the second-most common. Dr. Seuss included two cans and a boot in his cutaway view of McElligot’s Pool (“‘Young man,’ laughed the farmer / ‘You’re sort of a fool! / You’ll never catch fish / In McElligot’s Pool!’”), along with a teakettle, a milk bottle, a whiskey bottle, and a busted alarm clock. Since fishermen keep their worms in a can (was it once possible to buy canned earthworms?), it figures that some of those cans would end up in the water, but boots are just a funny form of litter. A trash-strewn cartoon alley is sure to feature both, not just because both are thrown at ALLEY CATS and songful DRUNKS, but because back in the good old days, when civilization was only beginning to be poisoned by its own excretions, these mass-produced and inconveniently durable objects must have been just troubling enough to laugh about.

Fig. 140 From Li’l Abner, 1949

{Li’l Abner © Capp Enterprises, Inc. Used by permission.}

Shoes were also thrown at newlyweds by the groom’s fun-loving friends, if the groom’s friends were drunken assholes. Dagwood Bumstead is beaned by a flung shoe on his wedding day as he leaves the church with Blondie. The custom was so common—if not in real life, at least in comedy—that Ira Gershwin wrote a song about it:

You may throw all the rice you desire,

But please, friends, throw no shoes.

For ’twill surely arouse my ire,

If you cause my wife one bruise.

—“YOU MAY THROW ALL THE RICE YOU DESIRE,” 1917

There is something expressive, almost touching, about a discarded shoe—maybe because we know it did a dirty job for years and now is tossed aside ungratefully. Not everyone, of course, could afford to throw away old shoes. Because many victims of the Great Depression blamed their poverty on Herbert Hoover, shoes with holes in them were referred to in the 1930s as “Hoover shoes” (just as newspapers used for warmth were “Hoover blankets,” wild rabbits used for food were “Hoover hogs,” and pockets turned inside out to emphasize their emptiness were “Hoover flags”). No other article of clothing is so often used to indicate the poverty of its wearer, be he a HOBO with his toes protruding, or a HILLBILLY with holes in the soles of his clodhoppers. But better old shoes than no shoes at all.

Everything is funny as long as it is happening to someone else.

—WILL ROGERS

IT IS USUALLY portrayed as a HILLBILLY custom: some outsider—generally a city slicker, often a TRAVELING SALESMAN—has dallied with Paw’s nubile daughter and either been caught in the act or made the mistake of returning to the same hills a year later, when the evidence of his transgression is unignorably present in the shape a swaddled infant. And now Paw and his shotgun are going to make the young man do the honorable thing. Not that the young man needs to impregnate the hillbilly gal to seal his fate; in some parts, the Code of the Hills dictates that even a kiss has the binding force of a formal marriage proposal.

Sometimes the gag is varied by making the father something other than a hillbilly, and his persuader something other than a shotgun. A 1963 cartoon showed the young man, his sweetheart, and her angry father all dressed in swimsuits, goggles, and flippers, and still dripping from the ocean; the couple stands before a justice of the peace, and the father holds a harpoon gun at the groom’s back. A 1947 cartoon by William Standing, a Native American artist, sets the scene on a reservation. The priest and the middle-aged groom are white; the bride is a Native American, and her father makes do with a bow and arrow. A Charles Addams cartoon showed a pith-helmeted explorer being wed at blowgunpoint to a bare-breasted pigmy.

Fig. 141 Invitation to a wedding. See also HILLBILLIES, YOKELS AND HICKS.

A related joke of the same vintage is the breach-of-promise lawsuit—the shotgun wedding’s hifalutin city cousin, so civilized that it furnishes the premise of a Henry James story (“The Bench of Desolation”), as well as a musical (We’re in the Money), a Mae West comedy (I’m No Angel), and an episode of Amos ’n’ Andy where Andy avoids the suit by faking SUICIDE. Robert Benchley was thinking of such lawsuits when he wrote, in 1930, “Sand is also a good place on which to write, ‘I love you,’ as it would be difficult to get into court after several years have passed.”

Three more years and our encyclopedia will be finished.

Let’s not bog down in the middle of the letter S.

—GARY COOPER, BALL OF FIRE, 1941

“THE FOX KNOWS many things, the hedgehog one big thing,” wrote Archilochus, invoking two animals insufficiently funny to merit entries in this guide (though a truly unabridged encyclopedia of humor would have to say a word or two about the hedgehog). The skunk, too, knows one big thing, and it’s so different from what most animals know as to muddle our notions of physical courage. A 1940s issue of World’s Finest Comics shows Superman, Batman, and Robin fleeing in panic from a skunk. We can debate whether it’s brave or merely foolhardy to stand your ground when faced with a hostile rattlesnake or rottweiler or redneck, but when the hostile critter is a skunk, there’s no argument. Reckless courage flourishes in shame cultures where the prospect of losing face is more daunting than that of death or grievous bodily harm. If skunk spray were lethal, manly men would be more likely to risk the creature’s wrath. As it is, there’s no glory in killing a skunk, and if it beats you to the draw, you end up stinking for a week.

Fig. 142

Since skunks are proverbially smelly, one way to insult someone is to suggest that he is even smellier than a skunk. In “Tokio Jokio,” a virulently anti-Japanese cartoon made by Looney Tunes in 1943, we see a panicky Japanese general running through a forest in search of somewhere to hide during an air raid. He finally dives into a hollow log that proves already to harbor a skunk; with a look of horror, the skunk hastens to put on a gas mask.

The most famous cartoon skunk is Pepé Le Pew, and what makes him funny is comic obliviousness: not only does he persist is misconstruing unambiguous sexual rejection as mere coyness, but he repeatedly mistakes cats for skunks. Depending on which of these misunderstandings we focus on, the Pepé cartoons can be viewed either as devastating satires on male sexual aggressiveness or as sinister anti-miscegenation fables. Or of course as neither. However you interpret them, you must admire their creator, Chuck Jones, for his ingenuity in devising one way after another for a cat to wind up looking like a skunk. Only once, in “Really Scent,” is the unlucky feline simply born with a white stripe. More often she acquires it by accident in the course of the cartoon (as in “A Scent of the Matterhorn,” where she happens into the path of a street-painting machine), or on purpose (as in “Heaven Scent,” where a cat paints a stripe down her back to ward off dogs), or as part of someone else’s scheme (as in “Two Scents Worth,” where a bank robber paints a stripe on a black cat in order to clear out a bank).

In “Private Ralph Skunk,” the third episode of Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C., Gomer finds and adopts a skunk, predictably annoying Sergeant Carter, and names the critter fondly after his uncle Ralph. Only someone as stupid as Gomer, you’d think, would name a skunk in tribute to someone, and yet Walt Kelly modeled Mam’selle Hepzibah—the sexy French skunk in Pogo—on his French mistress, who became his second wife. In her case, the choice of comic-strip avatar may have been determined by the comic French accent and difficulty with English that the second Mrs. Kelly evidently shared with Pepé Le Pew (who predated her), as Mam’selle Hepzibah certainly does. “Never dark on my door again!” she exclaims at one point to a fickle boyfriend.

And in fact, it makes sense to draw your adorably cute mistress as a skunk, since cartoonists usually do portray skunks as adorably cute. But also as pitiable: Caspar the Friendly Ghost was constantly befriending them. With the exception of Le Pew, cartoon skunks are usually juvenile and, like paintings of big-eyed waifs, designed to tug at heartstrings. Their stink is a metaphor for a baby’s dirty diaper as well as for social stigmas of every kind.

THIS JOKE IS seldom encountered except in single-panel magazine cartoons. In one from 1950 by a not-yet-famous Mort Walker, two Indians regard a distant mushroom cloud; one says to the other, “Whoever it is, he sure uses big words.” Most of the cartoons, though, involve the transposition of some aspect of telephony into a low-tech, pre-electric, Native American key; an “original” smoke signal cartoon is one that adapts a feature of phone communication that we haven’t seen adapted in previous cartoons. In a 1959 cartoon from Boy’s Life, for example, an Indian couple stands at the edge of a bluff above a huge heap of flaming timber. As the woman uses a blanket to send smoke signals, her husband says, “I hope you realize what these long distance messages cost!” Even at their best, such cartoons are ingenious rather than funny; if we laugh, it is a laugh of admiration—at Peter Arno’s ingenuity, for instance, in imagining a cliff-dwelling Indian couple responding to distant puffs of smoke. The husband has built a little signal fire in front of their dwelling, but his squaw calls down to him from a higher ledge where she too has a fire: “Never mind. I’ll take it up here.”

Sometimes an analogy is made with letters rather than phone calls. In a wartime Charles Addams cartoon, one Indian produces dark puffs of smoke and another Indian perched on a higher cliff uses a stick to disperse certain puffs. Looking on, one squaw remarks to another: “They’re censoring everything now.”

Since an inveterate bore can bore you by semaphore, hand signing, or even body language, it’s not surprising that smoke signals too can be boring. In a 1966 cartoon by Charles Rodrigues, two Indians stand by a small campfire, one holding a blanket of the sort used to send signals, and both watching an enormous cluster of separate smoke puffs from another, distant campfire. Says one Indian to another, “You never should have asked him about his operation.”

I am pretty sure that, if you will be quite honest, you will admit that a good rousing sneeze, one that tears open your collar and throws your hair into your eyes, is really one of life’s sensational pleasures.

—ROBERT BENCHLEY

THE FIRST MOTION picture copyrighted in the United States, “Edison Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze” (1894), was a five-second film of a man taking a pinch of snuff and sneezing. The man, Fred Ott, was an employee of Thomas Edison known for his sense of humor and the violence of his sneezes. Since the birth of cinema, then, sneezes have been associated with humor, though seldom as closely as in Robert Benchley’s pseudoscientific 1937 essay “Why We Laugh—Or Do We?,” which asserts that “all laughter is merely a compensatory reflex to take the place of sneezing.” After all, Benchley points out, when we say that something is “nothing to sneeze at,” we mean it is nothing to laugh at. “What we really want to do is sneeze, but as that is not always possible, we laugh instead. Sometimes we underestimate our powers and laugh and sneeze at the same time.”

The most common cause of sneezing in American cartoons is ground pepper. Like onion tears, pepper sneezes are especially funny because of the impressive reaction to a purely mechanical trigger. But all sneezes are funny. As mentioned elsewhere in this guide, NOSES often stand for PENISES, and no other physiological phenomenon is as similar to an orgasm as a sneeze: the gradual excitation, the point of no return, the violent release, and even the ejaculate.

Sloppy serial orgasms of uncontrollable sneezing were the main symptom of sitcom allergies, back in the golden age before we came to associate allergies with anaphylactic shock. As a rule, the allergy was—or seemed at first to be—to another character, the funniest one for the sufferer to be allergic to. So of course it’s Dennis who makes Mr. Wilson sneeze in a 1963 installment of the Dennis the Menace show. Skipper develops an allergy to Gilligan, and then, just in case that’s not funny enough, so do all the other castaways. Meanwhile, on The Patty Duke Show, Patty seems to be allergic to her identical cousin, Cathy, while over on The Dick Van Dyke Show, Rob fears that he’s allergic to his wife, Laura. On Petticoat Junction, Steve Elliott is banned from his own house because his baby seems to be allergic to him. Luckily things almost always work out in the end, when it turns out the allergy isn’t to the person per se, but to some nonessential aspect of the person, like the papaya oil in Gilligan’s new hair tonic.

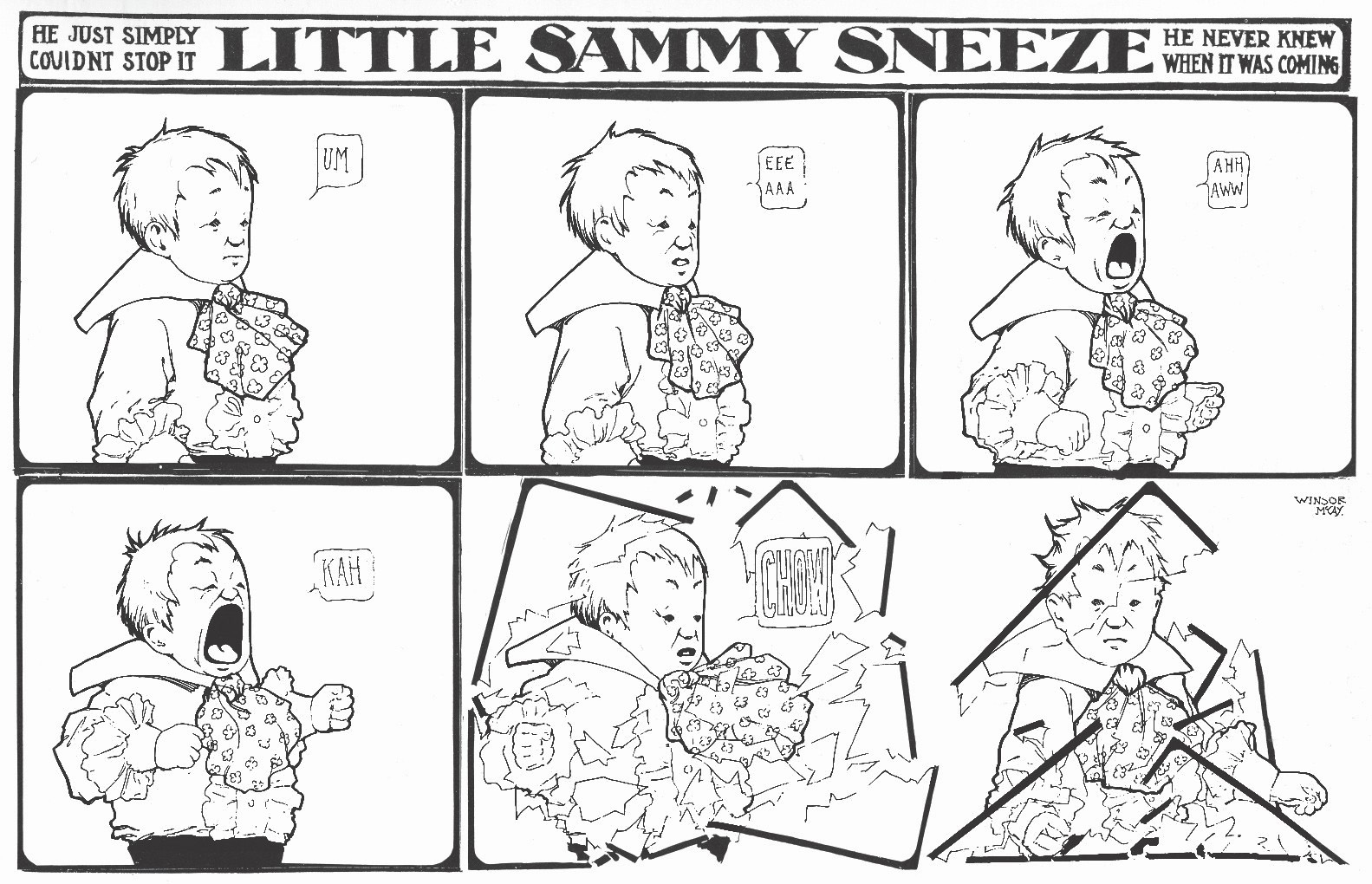

Fig. 143 One of Winsor McCay’s many one-joke strips: Little Sammy Sneeze, 1904

Another funny thing about sneezes is that they also occur among nonverbal beings like cats and dogs and mutes. Harpo never says a word in any of the Marx Brothers movies, but he sneezes audibly in At the Circus. Scooby Doo’s sneezes are a running gag, especially likely to occur when he and Shaggy are hiding and need to keep silent, and though no funnier than the rest of the show, they usually elicit a laugh from the laugh track. (And it is funny when animals sneeze. YouTube has many videos of sneezing animals, always with human laughter in the background.)

Like joy buzzers, sneezing powder was a favorite weapon of bad guys on the old Batman show. In one episode, when the dynamic duo raid an apothecary shop, one of the villains incapacitates them with a handful of sneezing powder, evidently something apothecaries keep in stock. Batman should have taken precautions, as he did in another episode from earlier in the same year (1966), when the Joker tried the same form of chemical warfare. “No use, Joker,” says Batman impassively. “I knew you’d employ your sneezing powder, so I took an Anti-Allergy Pill! Instead of a sneeze, I’ve caught you cold!”

There are also jokes about the art of sneezing. “Contrary to the prevalent fallacy, sneezing into the gas mask is to be avoided rather than practised,” advised Wally Walgren, a cartoonist and Marine, in the caption to a cartoon that appeared in Stars and Stripes during World War I. The drawing shows a doughboy blowing off his gas mask, and incidentally his helmet, with a thunderous “KAH-CHOW.” “If a sneeze is absolutely unavoidable, let it be through the ears . . . as the ears are not covered and afford a free air passage.” And about fifteen years later, Dr. Seuss—or rather a Seuss character, Dr. Farquarharson Fohsnip—declared that “not one child in a hundred can sneeze with grace.” Dr. Fohsnip conducts sneezing tutorials, where children listen to phonograph recordings of world-class sneezers like Sinclair Lewis, Mussolini, and Lydia Pinkham.

THE MOST ANNOYING snore in all of twentieth-century humor probably belongs to John Bickerson, the harried husband played by Don Ameche on the radio comedy The Bickersons. For its time (1946–51), the program was striking, even scandalous, in its portrayal of a marriage gone sour—a portrayal that foreshadowed the vision of marriage offered by The Honeymooners and, much later, Married with Children. In an era of model couples like Ward and June or Ozzie and Harriett, The Bickersons voiced a dissenting opinion of America’s most sacred institution. When they’re both awake, John’s shrewish and carping wife, Blanche, is more annoying by far, but when he manages to falls asleep, John gets his own back with a deafening, mucusy snore punctuated by high-pitched giggles (convincing Blanche that John is dreaming about their sexy next-door neighbor, Gloria Gooseby). Most of their fights are provoked by Blanche waking John in the middle of the night—and insisting on talking—in retaliation for his snoring.

Like MIDNIGHT SNACKING, snoring was a handy metaphor for sexual incompatibility, in an era that couldn’t talk about sex as directly as ours does. “Ma—he snores!” says the bride to her mother in an emergency wedding-night phone call (on the front cover of a racy 1956 Ace paperback collection entitled Love and Hisses), as her new husband sleeps in the bed behind her and a suitcase labeled JUST MARRIED stands by for clarification.

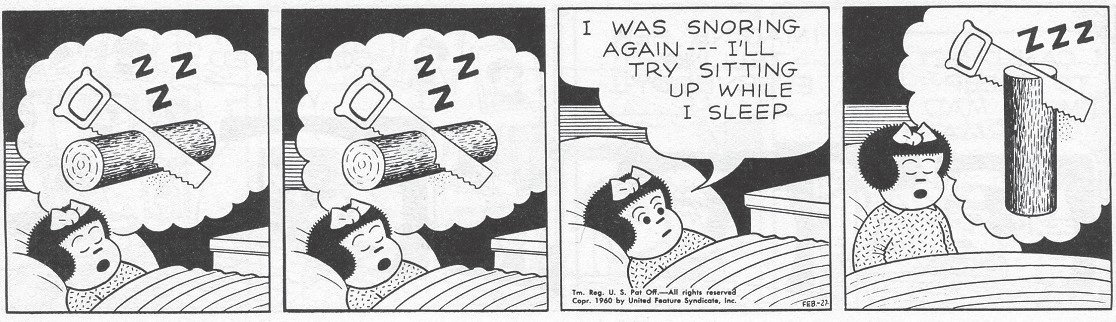

In comic strips, the standard way to indicate snoring is with a handsaw cutting a log in two. Usually the saw and log are tidily enclosed within an ordinary speech balloon, though sometimes the cartoonist will make the balloon more nebulous, to acknowledge the fact that the “speaker” is sleeping and the contents of the balloon is not a word or even an onomatopoeia, but an image. Given how common the “sawing logs” convention was in early comics—Barney Google alone must have snored his way through a cord of firewood per annum—it’s odd that cartoonists almost always felt the need to accompany the image with at least one “zzz” or “bzz,” a redundancy suggesting a mistrust of strictly visual storytelling. One of the quaintest things about early comics is the cartoonists’ obvious uncertainty as to how much could be told through pictures alone.

Why a saw? Why a log? The cliché dates back to an era when wood-stoves were more than just a cozy and nostalgic way for suburbanites to pollute, and when handsaws were not just for handymen and carpenters. The sawing of wood was an everyday sound, and a handy approximation of an everynight one. But a poor approximation, one that understates how funny, loud, and irritating real snoring can be. (Arguably, it’s not approximation at all, but rather the substitution of a funny image for a funny noise—a sight gag for a sound gag, as befits a medium whose real glory has always been visual, not verbal.)

Fig. 144 Nancy, 1960

{Nancy © 1960 Guy and Brad Gilchrist. Reprinted by permission of Universal Uclick for UFS. All rights reserved.}

No cartoonist was fonder of sight gags than Ernie Bushmiller, the mastermind we have to thank for Nancy, and no cartoon child snored more than its title character. In one strip, Nancy saws right through the log and wakes up when its end drops off. In another, she falls asleep sitting up and her snore is symbolized by a saw cutting lengthwise through an upright log (Fig. 144). In a third, she goes to sleep with a clothespin on her nose to muffle her snores, and the saw in the log is replaced by a pocketknife cutting through a pencil.

You seldom see comic-strip characters sawing through logs nowadays, though we continue to find logs per se funny—certainly funnier than boards or trees or sawdust. (Think of the Log Lady on Twin Peaks, or of Ren and Stimpy’s singing commercials for Log.) As for animated cartoons, the saw-in-the-log gag was never as common there. With a soundtrack there’s no need for symbols to indicate snoring, and animators have found other sight gags, better suited to the medium, to accompany the sound: the sleeper’s belly rising and falling massively, as Fred Flintstone’s does when he naps in his hammock, or the blanket over a supine snorer’s chest furling and unfurling with each breath.

Recalling the thunderous snorts and long descending whistles that comprise Fred’s snores, I’m reminded of exactly how inadequate “zzz” is as a written notation for snoring. Suppose you wanted to convey the sound more accurately in print. How would you transcribe it? On a comic postcard dating from 1911, a wife is shown sitting up in bed scowling at her sleeping husband, whose snores are spelled out “Z-Z-Z-Z-R-R-R-R-Z-Z-Z-Z-R-R-R-R”—a transcription that at least acknowledges that snoring is a two-part sound like sneezing in its rhythmic alternation of inhales and exhales. Don Martin, whose ear was prodigious as his eye, came as close as anyone to the quiddity of snoring—especially the hiccupy or apneac variety—with onomatopoeias like “ONNNNNGHK FWEEEEEEEEE” and “ZZZZ ZZT-ZNIK SNUFFLE SNORK.” Don Martin is dead, though, and no one has stepped forward to fill his giant floppy SHOES.

Fig. 145 No soap radio?

ALL PERSONAL-HYGIENE ITEMS are funny—mouthwash, toothpaste, toilet paper, and so on—but soap may be the funniest. Cartoon HOBOES exhibit a phobic reaction to the substance, and all-American boys aren’t too fond of it either, especially when having their mouths washed out49 or being told to wash behind their ears. In a 1941 episode of Nancy, the title character uses a bar of soap to scare the HICCUPS out of Grimy Gregory (her strip’s forgettable answer to Pig-Pen). The soap in the bathtub is probably the second-leading cause of indoor comic PRATFALLS, after the roller skate on the stairs.

Over the decades, the Johnson Smith Company has offered a product variously labeled as Dirty Soap, Sucker Soap, and Forget-Me-Not Trick Soap, which looks and feels like ordinary soap (and claims to smell like it, too: “gardenia scented”) but contains a water-activated dye that will blacken the face and hands of anyone who uses it. “Exceptionally good for BOARDING HOUSES,” claims one 1940s ad; and one reason I’m glad I don’t live in a boardinghouse is that they’re just the kind of place where you’d encounter practical jokers who shop from the Johnson Smith catalog.

In taking any liquid either from a spoon or drinking vessel, no noise must ever be made.

—EMILY POST, ETIQUETTE, 1922

“SOUP IS STILL funny, but not as funny as it was a few years back,” pronounced Irwin S. Cobb, author of Eating in Two or Three Languages (1919). It’s safe to say that many people have agreed with Cobb about the basic funniness of soup, including the several cartoonists for whom a favorite last-panel sight gag is a bowl of soup upended on somebody’s head. What bricks are to Krazy Kat, and pies to the Three Stooges, soup is to Mutt and Jeff; Jeff often works as a waiter, and more often than not, when someone orders soup, someone will be wearing it before the meal is over.

Why is soup funny? Because it’s messy? Because it’s neither meat nor drink? Because it often serves (or did in my house when I was a kid) as a punitive or penitential surrogate for more substantial food? Because, like SAUSAGE, it’s a way to use up leftovers and parts that no one would otherwise eat?

One reason is that it’s noisy. “The soup sounds good,” observes the Great McGonigle in The Old-Fashioned Way (1934), on hearing a meal in a BOARDINGHOUSE. In a pre-Popeye episode of Thimble Theatre, Olive Oyl makes soup for herself and her boyfriend, Ham Gravy, but he makes so much NOISE eating it—not slurping but slupping, to judge by the “slup slup slup” sound he makes—that she flounces off in disgust, abandoning her bowl to a roaming hog that makes the same slupping noise. Soup is an ambiguous food, neither solid nor liquid, too thick to be sipped from a cup but too thin to be forked into the mouth. Especially when it’s piping hot, it almost demands to slupped, pace Olive Oyl and Emily Post. And here—I announce it beforehand for the sake of readers who prefer to skip such things—is a scatological limerick:

There was an old fellow from Roop

Who’d lost all control of his poop.

One evening at supper

His wife said, “Now Tupper,

Stop making that noise with your soup!”

Its noisiness was so proverbial a hundred years ago that Guy Wetmore Carryl, in his retelling of “Little Boy Blue,” compares the sound of rogue cows tramping around in mud to the sound of schoolboys eating soup, instead of the other way around. In a 1934 New Yorker cartoon by William Steig, a sort of field guide to different types of eaters (the Slow Careful Masticator; the Jackal who raids the icebox in his pajamas; the Pseudo-Correct, who extends the pinky on her crumpet hand as well as the one on her teacup hand), the Beast is a fat man slurping his soup. “You can get all the noise you want out of a tramp and a bowl of soup,” reads the caption to one of Rube Goldberg’s simpler cartoon inventions, a New Year’s Eve noisemaker consisting of a chair tied to a reveler’s back with what looks like a piece of ordinary kite string; a tramp sits in the chair noisily spooning up a big bowl of soup with a ladle, and a sort of giant hearing trumpet mounted on the chair collects the ensuing noise and broadcasts it to the world at large.

And what exactly is the noise of a man eating soup? Slup slup slup? No, “GURGLE GURGLE GURGLE,” according to Goldberg. Don Martin hears it differently: “SLURK GLURKLE GLUP SLOOPLE GLIK SPLORP SHPLIPLE DROOT GLORT.” The soup dripping back into the bowl from the spoon gets its own sound effect: “DRIPPLE BLIT.” (According to Martin’s precursor as Mad’s Maddest Artist, Basil Wolverton, the sound of a glass eye falling into a bowl of tomato soup is “PLOOP!” while that of a glass eye falling into heavy syrup is “PLOFF!”) Martin found the sound of soup so funny that in a Mad cartoon entitled “Last Week in a Freensville Diner,” we see a man eating soup for three successive panels, surrounded by those trademark slurping sounds. In the third panel, the hefty cook asks, “How’s the soup, pal?” In the fourth, the man stops eating and replies “Too noisy!!” while the soup itself continues to make noises: “GLIP SHPIKKLE GLUP GAPLORK.”

We associate soup with poverty and illness—with charity kitchens and sickrooms. When, in a famous early sequence of Blondie strips, Dagwood goes on a hunger strike to protest his millionaire parents’ refusal to let him marry lowborn Blondie Boopadoop, the latter suggests squirting soup down his throat with a bicycle pump, and a week later takes the liberty of injecting hot soup into his arm with a hypodermic needle. Toward the end of the strike, when Dagwood’s condition is critical, his millionaire parents resort to force-feeding, which involves an elaborate array of tubes and tanks and motors and two nurses bearing giant vats labeled CONCENTRATED CLAM BROTH and CONCENTRATED CHICKEN BROTH.

Some old jokes about bad restaurants emphasized the thinness of the soup du jour, which sometimes contained little more than water and the occasional housefly. In “The Soup Song,” a zany 1931 cartoon, Flip the Frog works as a waiter and cook in a cheap eatery. In one scene, we see him make soup by dipping various items briefly in a pot of boiling water—first a bunch of carrots, then a CABBAGE, then a wedge of Swiss, then an old boot, and finally a plucked chicken that is resurrected by immersion just long enough to towel off like a bather (a faintly naughty joke, since after all a plucked chicken is a naked female).

Soup is a funny place to find things that don’t belong, whether the thing is a fly, the tip of an old man’s beard, the overalls in Mrs. Murphy’s chowder, or the camera that Maxwell Smart, posing as a butler, hides in the bowl he serves to a criminal in an episode of Get Smart. In an episode of Leave It to Beaver (“In the Soup”), the Beav gets trapped in a giant steaming bowl held by a giant Mom after climbing a billboard to see if there’s actually soup in the bowl (there isn’t). He is rescued, in the end, by the fire department.

Mothers who raise

A child by the book

Can, if sufficiently vexed,

Hasten results

By applying the book,

As well as the text.

—W. E. FARBSTEIN

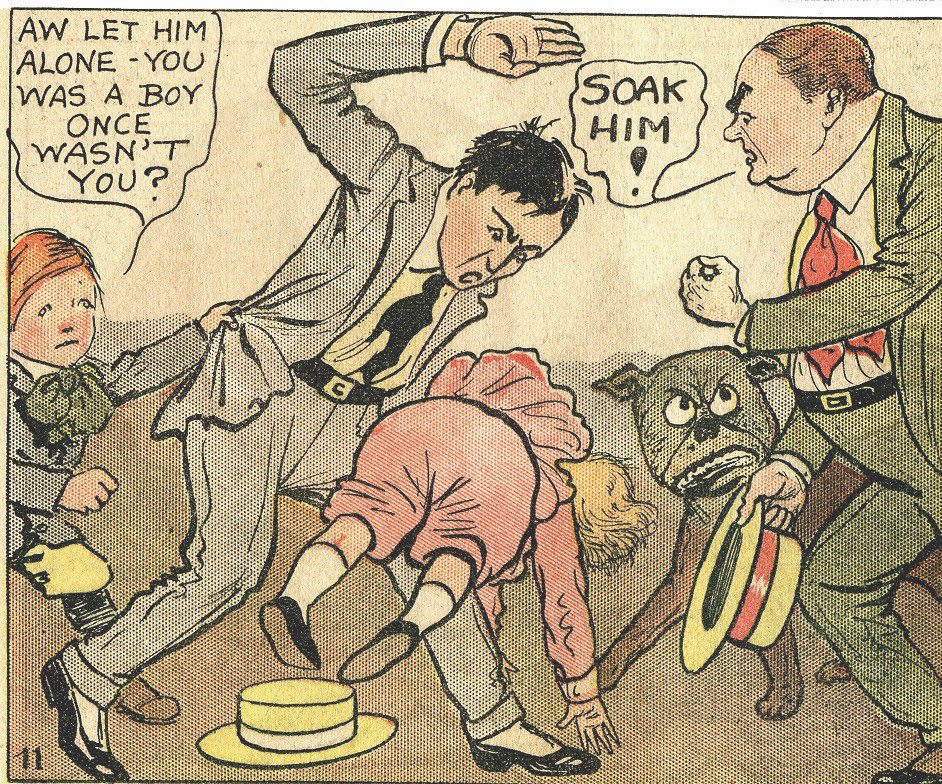

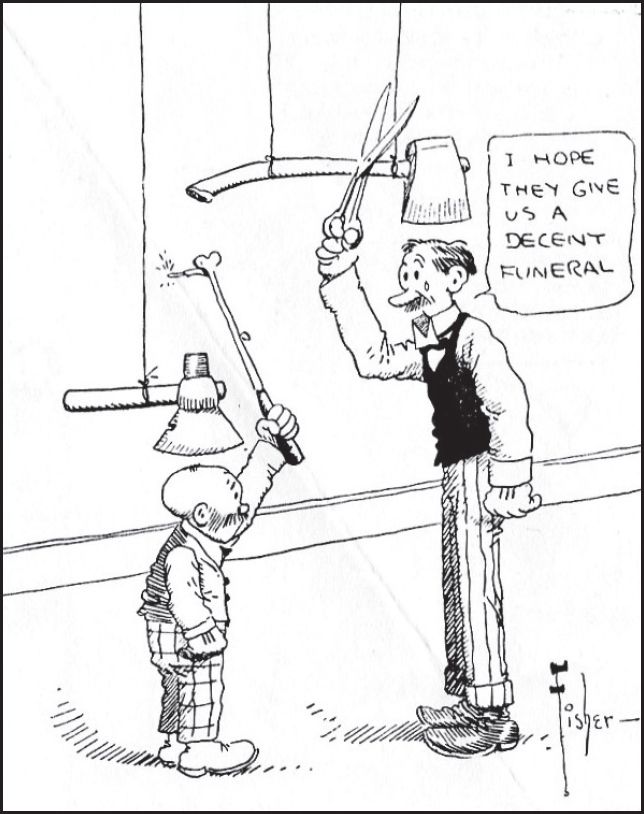

THE KATZENJAMMER KIDS began in 1897, when its creator, Rudolph Dirks, was nineteen years old. It was the first comic strip to appear regularly in color, and it racked up all sorts of other firsts as well: Dirks, for example, pioneered the saw-in-the-log ideogram to indicate SNORING. He also established most of the conventions regarding corporal punishment in comics—not surprisingly, since almost every day his strip ended with young Hans and Fritz getting spanked. Their long-suffering mother delivered so many spankings that the activity changed her musculature; at least, that’s how I explain her presence on the short list of comic-strip characters (the only others who come to mind are Alley Oop and Popeye) with forearms bigger than their upper arms.

We’re so used to the conventions established by Dirks that we may fail to notice how stylized the standard comic-strip spanking is. We never see a hand or hairbrush striking a bottom, for instance, but always raised to strike. If there’s only one authority figure on the scene to administer two spankings, we are always shown the second; the first malefactor is already crying.

Few later comic-strip tots were quite as demonic as Hans and Fritz. Dennis the Menace (1951–present) wreaked just as much havoc, but never maliciously. As with Bill Watterson’s Calvin (clearly indebted to Dennis), most of his mischief was due to the dissonance between his worldview and the grownups’, as when Dennis soaks his business-suited father with a garden hose because he thinks his dad looks too hot. Like Calvin, Dennis is punished not with spankings but with what we now call “time-outs.”

Fig. 146 Buster Brown, 1916

Why is spanking so much more common in old comics than in old movies? Mainly because comic strips allow and encourage all kinds of outrageousness that wouldn’t work in any other medium, not even the related one of animated cartoons. Just imagine how many aspects of Krazy Kat—the absurdly changing backgrounds, the constant violence against the most lovable character, the carefully maintained uncertainty as to that character’s gender and sexual orientation, the Joycean wordplay, the sheer oddness of the humor—would have to be lost or dialed down to convert Herriman’s vision into watchable cartoons. Not even Peanuts made the leap from comic strip to cartoon specials without signs of strain. As for the constant spankings in early comics, what might be unpleasant on film for all but the fetishists (who admittedly are legion) is merely amusing on the funnies page.

We tend to assume that our objections to real-life spanking never occurred—and would have made no sense—to the parents of a hundred years ago, but in fact the debate about corporal punishment goes way back, further than the hindsight of this book. Strips like The Katzenjammer Kids show a world where spanking was taken for granted, but also one where it accomplished nothing, and served no other purpose than sheer retaliation. If it had any deterrent value, why would Hans and Fritz reoffend day after day, every day, for decades? In one strip, as they watch their latest prank unfold, Hans says, “Something tells me we are going to get a licking,” and Fritz replies “Vat do we care? We’re used to it!” Decades later, Red Skelton made the same point with his “Mean Widdle Kid” routine: “If I dood it, I dit a whippin’ . . . I DOOD IT!”

The old phrase “Spare the rod, spoil the child” (which dates back to the 1600s in that form, and ultimately to the Old Testament) shows that some people have always inclined to spare the rod. Dickens pointed out in several of his novels the needless cruelty of school floggings, and a little earlier Wordsworth had gone further, implying that if floggings aren’t needless in the classroom, so much the worse for classrooms. At least that seems to have been one reason he and his fellow Romantics bore such a grudge against traditional pedagogy: a sense that there must be something unnatural about a learning process that needs to inflict so much bodily pain. A century later, Orwell wrote, “I doubt whether classical education ever has been or can be successfully carried out without corporal punishment,” though out of context that could pass for a pro-spanking sentiment.

In a 1909 installment of The Dingbat Family, a pre–Krazy Kat comic strip by George Herriman, Mrs. Dingbat returns from a meeting of her woman’s club just as her husband is about to spank their rotten son Cicero for disrupting his nap. Like a governor phoning in a last-minute stay of execution, she tells Mr. Dingbat that “the Mothers’ Council have just decided that spanking destroys the sub-conscious spirituality of the child.” (“Well,” replies her husband, “he had no consideration for my sub-conscious spirituality.”)

Of all the topics in this guide, spanking was the easiest to research online, because I soon found that a horde of spanking fetishists had already done the spadework, and more lovingly than a mere student of humor ever could. Thanks to this anonymous but public-spirited network of pervs, I can say with confidence that in the 1940s, right around the time that wartime labor shortages were giving women a chance to work in munitions factories, a great change took place in American comics: after decades of standing by sweetly while their brothers were spanked, little girls had their turn. Art, as Cocteau said, is forever looking for the fresh spot on the pillow, and comic artists found one such fresh spot on the bare or panty-clad buttocks of such tykes as Little Audrey, Little Dot, Little Iodine, and Little Lulu (the earliest of the four—she received her first spanking in 1935). Their exploits took place for the most part not in wholesome family papers but in comic books, as befits a fad that often verged on fetish porn. If the daily spankings of Hans and Fritz were primitive morality tales of crime and punishment, the spankings in the little-girl comic books were ends in themselves. There wasn’t even always the pretext of misbehavior before the baring of the little girl’s buttocks; sometimes a bully would administer a wholly gratuitous spanking, not in loco parentis but rather on behalf of the deviants who clearly made up an important part of the readership.

The fad for little-girl spankings was oddly predated by a fad, in superhero and adventure comics of the 1930s, for big-girl spankings. Manly men like Mandrake the Magician, Price Valiant, and the Phantom often dealt with spoiled socialites and other difficult young women the same way the mother of Hans and Fritz dealt with their mischief. Like the little-girl spankings of the 1940s, these retributions often suggested a fetish on the part of cartoonist and reader alike, though sometimes corporal punishment was a simple assertion of male prerogatives, like Ricky Ricardo’s spankings of Lucy. Lucy is more spirited and more articulate than her spouse, but Ricky is the man in a world where men are in charge, and when all else fails he can put his wife in her place as surely as a parent does a misbehaving toddler, by spanking. (The same solution is advocated in our own time by stern proponents of the school of wife-rearing called Christian Domestic Discipline.)

Spanking, of course, wasn’t the only form of parental or quasi-parental beating practiced in that era (though, for reasons that deserve a closer look, it’s the one that fascinates our culture). In Nize Baby, Milt Gross’s illustrated hörspiel of immigrant life in the mid-1920s, little Isidor receives hundreds of carefully transcribed smacks in the course of his father Morry’s tirades:

So, Isidor!!! Benenas you swipe from de pushcar’, ha? (SMACK!) A Cholly Chepman you’ll grow opp, maybe, ha? (SMACK!!) I’ll give you. (SMACK!) Do I (SMACK!) svipe? (SMACK!!) Does de momma (SMACK!!!) svipe? (SMACK!!!) From who you loin dis? (SMACK!)

Speaking of Cholly Chepman: in Tillie’s Punctured Romance (1915), Charlie spanks a tiger rug after it trips him—but considering that earlier in the same film we’ve seen him throw a brick at Marie Dressler’s head, the tiger gets off pretty easy. (In a Moon Mullins strip from 1934, Mullins spanks a pet parrot after its abusive language earns its owner a black eye from a passerby.) Buster Keaton began his showbiz career as a battered child in the family vaudeville act, the Three Keatons. Billed as “The Little Boy Who Can’t Be Damaged,” young Buster would provoke his father into throwing him across the stage or even into the audience. To facilitate this rough handling, Buster had a suitcase handle sewn onto his clothing. And people paid to watch.

AFTER DITZINESS AND bossiness, the trait most often imputed to wives in the mainstream humor of the early and mid-twentieth century was prodigality. The classic emblem of that trait was the wife returning from a shopping expedition with a big stack of parcels, and saying something cute to her shocked or fuming spouse. Invariably one of the boxes was a big round hatbox—because nothing better emblematizes the frivolity of women’s spending habits (as seen by their husbands) than women’s hats.

In the middle of the last century, binge shopping was depicted as a strictly female addiction. In a gag cartoon from a 1960 compilation called Thimk, the whole joke is that the husband comes home with the parcels: “Got feeling low—bought a new hat, new suit, couple of ties.” Real men didn’t care what they wore.

In the racier humor of the era, the most common failing of wives was infidelity. Women were often portrayed as GOLD DIGGERS—as de facto prostitutes auctioning their bodies to the highest bidder. Was the compulsive-shopping gag a cleaned-up, G-rated expression of deeper male anxieties about the unbridled appetites and mercenary nature of the female?

One man’s poison ivy is another man’s spinach.

—GEORGE ADE

This would be a better world for children if the parents had to eat the spinach.

—GROUCHO MARX IN ANIMAL CRACKERS, 1930

WILL ROGERS SAID, “An onion can make people cry but there’s never been a vegetable that can make people laugh.” He was wrong. People have been laughing at veggies for ages, just as they’ve been laughing at HASH and other unpopular foods. Admittedly, there’s no consensus as to which vegetable is funniest. Potatoes are surprisingly funny despite the fact that no one seems to hate them. CABBAGE has inspired enough mirth to merit its own entry, but just barely. Turnips, too, might have merited an entry, if the root-vegetable vote weren’t split by parsnips, rutabagas, mangel-wurzels, and beets. For Will Cuppy, beets were funniest:

Fig. 147 “It’s broccoli, dear.” “I say it’s spinach, and I say the hell with it.”

Fig. 148

I dare say that pickled beets, with their deadly, soul-sapping monotony, have torn more fond hearts asunder, broken up more happy homes and caused more crimes of passion than any other three vegetables chosen at random. . . . pickled beet relish with all its brood of quarrels, flatirons and BRICKS.

—HOW TO BE A HERMIT, 1929

But the vegetable most often maligned by humorists is spinach, largely because it was the one most often forced on reluctant children. Spinach was the wonder food of the early twentieth century, a food believed to be ridiculously healthy, like pomegranate juice in our own time. One reason the Popeye cartoons got away with their unprecedented violence is that they were such effective pro-spinach propaganda. (Spinach never played as big role in Thimble Theatre, the Popeye comic strip, which originally attributed his strength not to eating a vegetable but to rubbing the head of an animal, the fabulous Whiffle Hen.)

In 1928, or just a couple of years before Popeye started campaigning for spinach, a New Yorker cartoon by Carl Rose showed a mother arguing at dinner with an adorable curly-headed little girl: “It’s broccoli, dear,” says the mother. “I say it’s spinach and I say to hell with it,” replies the girl. The answer became proverbial, and for the next twenty years or so, spinach was a synonym for bullshit. In 1938, a former fashion designer published a tell-all book about the fashion business with a title that no longer makes sense: Fashion Is Spinach.

The nationwide obsession with spinach and spinach-bashing seems to have peaked around 1930 (Popeye, whose first deployment of the stuff occurred in 1931, seems to have been as much a symptom as a cause of that obsession). A 1930 installment of a comic strip called Now You Tell One—a spoof of Ripley’s Believe It or Not—features “the wonder child of Cedar Carpets, Iowa. Loves to have his face washed (especially behind the ears), likes to go to school, hates school vacation and is particularly fond of eating SPINACH!”

Since then, spinach has become—like most of the laughingstocks considered in this guide—less and less lafftastic. That it was still a little funny in 1955 may be deduced from the menu at the vegetarian restaurant in The Seven Year Itch, which offers Spinach Loaf, along with such dishes as Soybean Sherbet, Dandelion Salad, and Sauerkraut Juice. In a 1958 Sunday episode of Hi and Lois where Hi (who was zanier in this youth) decides to do everything backward for one day, we see him at the dinner table happily eating chocolate ice cream while his wife and kids face platefuls of spinach.

Nowadays, people are more likely to joke about broccoli. I’ve never met anyone who named spinach as his or her least favorite vegetable, but of course it’s been a while since parents were zealous about ramming it down children’s throats. And Americans—especially the ones most likely to worry about healthy eating—have gotten better at preparing veggies. Eighty years ago, when the first Popeye cartoons appeared, most people got their spinach out of cans, like Popeye himself—and nothing makes a vegetable less appetizing than a stint in a TIN CAN.

When you consider what a chance women have to poison their husbands, it’s a wonder there isn’t more of it done.

—KIN HUBBARD

Ricky to Lucy: And as I recall, it was till death do us part.

That event is about to take place right now!!

—I LOVE LUCY

I’VE NEVER BEEN married, and I don’t know what to make of all the cartoons, sitcom episodes, and other works of humor involving murderous spouses. Do people joke about uxoricide because it’s so unthinkable, or because it’s a universal fantasy of long-suffering husbands and wives alike? How many spouses, on an average night, drift off to sleep with a smile on their lips and an ingenious fantasy of murdering the person SNORING next to them in the dark?

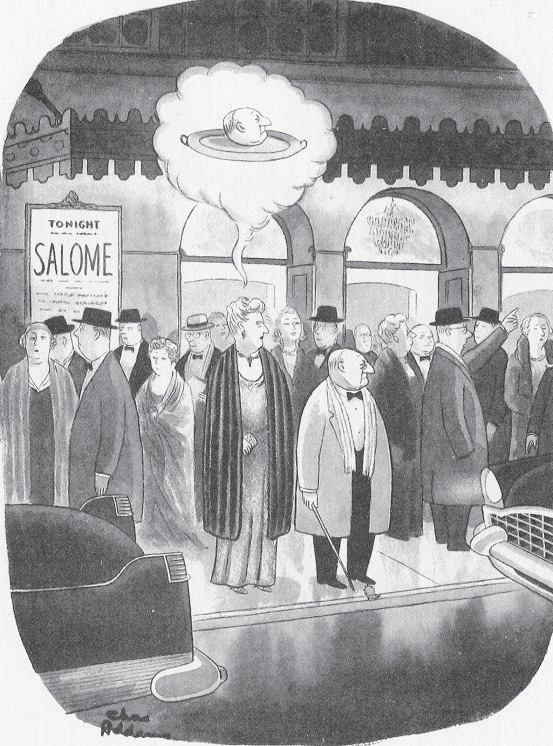

If Charles Addams were alive, we could ask him. No one was fonder of spouse-killing gags, though his favorite couple, the oddballs Morticia and Gomez, were too happily married to dream of such a thing. Actually, there is one cartoon from 1943 in which a tall, dark-haired woman who could be Morticia asks a bookstore clerk: “Do you have one in which a wife murders her husband in a very ingenious way?” As a rule, though, the domestic murderers in Addams’s famous cartoons were seemingly normal people: the plainly HENPECKED HUSBAND who parks his car and its wife-bearing trailer at the edge of a cliff and says, “Oh, darling, can you step out for a moment?”; the ultrarespectable OPERA-going society lady who emerges from a performance of Salome picturing her husband’s head on a platter. My favorite example, though, of Addams’s deceptively normal murderers is the brand-loyal wife who explains to the police:

. . . and then I disconnected the booster from the Electro-Snuggie blanket and put him in the deep-freeze. In the morning, I defrosted him and ran him through the Handi Home Slicer and then the Jiffy Burger Grind, and after that I fed him down the Dispose-All. Then I washed my clothes in the Bendix, tidied up the kitchen, and went to see a movie.

It’s notable how much spouse-killing humor there is in old sitcoms, since one purpose of those early-evening shows was helping married couples coexist by giving them something besides each other to look at. They can always read, of course, but they’d better stay away from murder mysteries, since—at least on sitcoms—those books have a way of convincing suggestible readers that their spouses are trying to kill them. Or of spooking the reader’s spouse. That’s what happens on “Dial S for Suspicion,” the Flintstones episode in which Wilma’s fondness of the mystery she’s reading, and her sudden eagerness for Fred to get life insurance, convince him that she’s about to murder him.

Is that really one of the fundamental comic misunderstandings—the delusion that your spouse is trying to kill you? I Love Lucy—an encyclopedia of comedic misunderstandings—had been airing for less than a month before it got around to a spouse-killing episode, “Lucy Thinks Ricky Is Trying to Murder Her.” Lucy is already jumpy from reading The Mockingbird Murder Mystery when she overhears and misunderstands a phone conversation, then finds what proves to be a fake gun in Ricky’s desk. She takes to carrying a garbage can lid as a shield, but then becomes convinced that Ricky has poisoned her orange juice, and heads to his club with that gun to shoot him.

Fig. 149 Charles Adams, 1956

{© Charles Addams. With permission Tee and Charles Addams Foundation.}

Juice also comes under suspicion in “Suspense,” the Honeymooners episode in which Ralph becomes convinced—after overhearing Alice and Trixie rehearsing a play about a murderous wife—that Alice plans to kill him. When he then sees her put a vitamin pill in his breakfast juice, Ralph accuses her of trying to poison her, then panics when she drinks the juice herself, as if she were that desperate to escape her marriage one way or another.

More often than not, the suspicion has its origin in a book or play or movie involving spouse-killing—in a character’s sudden and endearingly dumb conviction that life is imitating art, or that he or she is involved in the kind of story where people commit murder. Sitcom characters, of course, never do kill their spouses, though sometimes the producers will, when the actor quits the show while it’s still going strong. The first such casualty in television history was Margaret, the wife on The Danny Thomas Show, who was killed off in 1956 when the actress who played her (Jean Hagen) left the show.

It’s a truism that our culture is more comfortable with violence than with sex; in the days when that was even truer—when TV could show a double homicide but not a double bed—spouse-killing was sometimes easier to joke about than infidelity. So when I tell you that “So You Don’t Trust Your Wife” is a short comic film from 1955, you won’t be surprised to hear that the issue in question is not whether the wife of Joe McDoakes is sleeping with another man, but whether she is planning to murder her suggestible mate, who for no good reason begins to suspect the worst when she innocently asks him if his insurance policy is paid up. He doesn’t even want to let her rub his neck.

THE FIRST PUBLIC screening of motion pictures was held in 1895 by Louis Lumière, who showed ten very short films directed by him. Most of these were microdocumentaries, but there was also a comic anecdote entitled “L’arroseur arrosé” (“The Sprinkler Sprinkled”). This forty-four-second movie, which has been called the first comic film, involves a middle-aged man and an adolescent boy. The man is watering a lawn when the youth steps on his hose, interrupting the flow of water and causing the man to peer into the nozzle with a stupidity that foretells the whole future of film comedy. Then the boy removes his foot from the hose, which squirts the man in the face.

Fig. 150

{Nancy © Guy and Brad Gilchrist. Reprinted by permission of Universal Uclick for UFS. All rights reserved.}

If you think the symbolism Freud saw everywhere was just a figment of his filthy imagination, a good look at the humor of his era—the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—will convince you that he wasn’t the only one with a dirty mind. We all have dirty minds, in the sense of thinking a lot about sex; and when a culture forbids people to discuss or represent sex directly, they don’t think about it any less. They just discuss and represent it indirectly. There’s no other way to account for the bewildering profusion, in old humor, of jokes about squirting and soaking.

Garden hoses, seltzer bottles, squirting flowers, dunking stools, water balloons, plumbing disasters, puddles, brimming buckets above doorways—an intelligent being from a planet with humor but not water might conclude from earthling humor that there is something uniquely funny about that substance. In Snoopy’s first appearance, in the third-ever Peanuts strip (October 5, 1950), he gets drenched as he walks below Patty’s window with a flower affixed to his head just as she is watering the flowers in her window box. Chekhov famously wrote that if you show a gun above a mantelpiece in Act 1, the gun has to go off in Act 3. And it’s the same with squirt guns, hoses, and the like: if you show one in the first scene of a slapstick comedy, or the first panel of a comic strip, it has to soak somebody by the last.

If we grant that a train going into a tunnel can stand for intercourse, and a burst of fireworks for orgasm, we should at least be willing to entertain the proposition that the water squirting at people in a zillion comic strips, cartoons, and live-action comedies—and in real life from a zillion trick flowers and other squirting novelties—sometimes stands for urine or semen. Every baby pisses on its parents, and the urchins who squirt grownups in old comics are asking to return to that beatific state when such deeds were allowed because all was allowed. As for semen, men have been ejaculating in other people’s faces as long as oral sex has been around, and it’s safe to say that in any era where they couldn’t joke openly about such things, humorists have joked about them covertly.

Mad’s maddest artist, Don Martin, was especially fond of squirting flowers, and used them in many of his Mad cartoons. In one, a doctor attending to the owner of Irving’s Trick and Novelty Store is squirted in the face—with a “SHKLITZA”—by a vase of flowers at the convalescent’s bedside. In another, a man buys a squirting flower from Hal’s Novelty Shop and then tries it on a pedestrian, but the rubber bulb bursts messily in his pocket with a “SKLOOSH . . . glik glik glik glik.” (Anyone who doubts that the real gag with squirting flowers is about piss should reflect that the water is kept in a rubber bladder in the prankster’s pocket, close enough to his penis that if the bladder bursts, it looks like he’s wet himself.) In another, two men are walking on a beach when one is squirted in the eye with a “SHKLIKSA!” by something buried in the sand that turns out to be a clam. They stroll on, with the unique double-jointed gait of all Don Martin characters, until the other man gets squirted with a “SHKLIZICH!” by what proves to be a buried squirting flower. Nor should we forget the one where an Old Testament practical joker comes up to Moses and says, “Hey . . . get a load of my new boutonniere.” When the joker tries to squirt him, Moses parts the waters with a “GASHKLITZ.”

Flowers are the classic squirting novelty, but by no means the only one. The 1929 Johnson Smith catalog also offered a Squirt Pencil (“It is a good joke to play upon the inquisitive person who insists on looking to see what you are writing”), a Squirt Cigar Case, a Squirt Cigar Cutter, a Squirt Pipe, a Squirt Electric Button (which looks like a doorbell but squirts the caller rash enough to push it), a Squirt Pocket Mirror (“If charged with scent instead of water it will probably prove less objectionable to the ladies”), a Squirt Rubber Heart (imprinted with the words “Wiedersteht jedem Eindruck”—a suspicious number of laff-getters originated in Germany), a Squirt Rubber Snake, and a Squirt Mouse. By the 1940s, the company had added several new squirting gags, and anyone who doubts that the real joke has do with bodily fluids should consider the ad, in the 1942 catalog, for the Squirt Chocolate Bar: “‘Say, sweetie, have a piece of chocolate!’ This is the one all the girls ‘bite’ on. The chocolate bar is temptingly peeled open. As they reach for a piece, give the bar a gentle squeeze, and out shoots a stream of water.”

There are people who think that everything one does with a straight face is sensible.

—GEORG C. LICHTENBERG

There’s nothing that starts the adrenaline of a humorist going faster than a humorless man in power.

—WILLIAM ZINSSER

THE SIMPLEST DEFINITION of “stuffed shirt” might be “the sort of dignitaries made indignant by the Marx Brothers’ antics”: diplomats, mayors, COLLEGE PROFESSORS, judges, cabinet ministers, OPERA managers, and the like. (Their favorite victim was Margaret Dumont, but when the shirt in question is stuffed with a heaving BOSOM, its wearer is not a stuffed shirt but a DOWAGER.) The essence of Marx Brothers humor is deflating the pompous, shocking the prudish, outraging the respectable, toppling anyone who stands on ceremony, and generally refusing to play the game by other people’s rules, thereby revealing the absurdity and artificiality that govern so much of civilized life.