Pests in the garden are among the most annoying and difficult problems. No matter the growing method, pests can infect the garden. Pests travel on clothes and pets. This is a good reason not to allow animals in the grow room. Additionally, pests can also arrive on the wind, though no fault of people or pets.

Make sure that the planting mix is composed of inert or pasteurized ingredients. Planting mix that is not sterile or pasteurized can contain bugs.

The larger an insect infestation, the harder it is to eradicate, and, greater the chances that it includes pests that are resistant to chemical warfare.

This section provides information that allows you to recognize and eradicate pests that affect Cannabis plants. As with the nutrients, the pests are listed in alphabetical order, but the ones that are most likely to attack cannabis are aphids; fungus gnats; mealybugs; scale; broad, russet, spider and hemp mites; and whiteflies.

A description of each pest is provided so that you can detect it and the damage it does. Preventive and control methods are provided to keep the pest away from the plants and get rid of an infestation.

Ants are abundant both indoors and outdoors. Most of the species that affect marijuana use it for grazing their herds of aphids and mealybugs.

Ants are made up of three main body parts: the head, thorax and abdomen. All six legs are attached to the thorax. The eyes and the jaw and antennae are connected to the head. Ants are generally quite small, usually only about 0.1 to 0.2 inch (about 2 to 5 mm) long. While sexually reproductive ants have wings, the worker ants do not. The worker ants will be the ones you are most likely to see in your garden.

Ants can be found in the soil or planting medium, where they nest. They climb the stalk and graze their herds of aphids and mealybugs on the leaves.

They make their homes in underground colonies and must burrow to travel, thus causing damage to roots and root hairs. The aphids and mealybugs they herd are severe threats to plants because they suck vital juices and are vectors for disease.

Ants are attracted to plants that already have aphids, whiteflies, mealybugs and scale. Then they take these pests to new grazing areas. First they spread out on the plant and then move the herd to new plants. They will defend the herd from predators and parasitoids like ladybugs and parasitoid wasps. They hang out (in moving streams) on the plant and in and around the soil/medium.

Aphids, mealybugs and whiteflies secrete a sticky substance known as “honeydew,” which consists of a sugar concentrate made from the plant’s sap. Ants adore this honeydew, but this sticky annoyance causes sooty mold. Even if the plants do not have infestations of other pests, it is important to exterminate ants because of their ability to carry pests to the plants.

Depending on the pests trying to be controlled, select one or more species of beneficial nematodes. ARBICO Organics offers a large variety of nematodes, including Heterorhabditis bacteriophora, Steinernema feltiae and Steinernema carpocapsae. Mixed with water applied into the soil, applications should ideally be done twice yearly, in spring and in fall before pests overwinter.

Reproduction rate and life cycle: Ants are social creatures, living in colonies of queens and supported by workers. Some species have only one queen per colony, while others may have several. The adult’s life cycle begins with an egg laid by a queen, then progresses through a larval stage, a pupal stage and finally to adulthood. In many species only the oldest adults work outside the colony, while 90% of the ants work in the nest. Colonies reproduce when a newly hatched queen selects several males and either walks or flies to a new location.

Ants regulate their reproductive rates depending on conditions in the colony and the outside environment. They do this partly by varying the length of the pupal stage and partly by selecting certain larvae or pupae to be transformed into queens and drones. If weather is suitable and there is ample food and water for the size of the colony, they will reproduce faster, then slow down reproduction when conditions become less favorable. What this means to the gardener is that it is not enough to destroy only the ants you see. You need to eliminate the colony itself because lost workers are rapidly replaced.

There are many ways to deter ants from wandering into the grow area and getting to the plants.

Aphids in multiple life stages Photo by W. Cranshaw, CSU, Bugwood.org

Aphids are a common pest.

Aphids are small, pear-shaped soft-bodied insects about 1 to 3 mm long. Like all insects, they have six legs, a pair of antenna, and three body segments: head, thorax and abdomen. There are thousands of species that vary in color from green to yellow, black or brown. Some have wings, some are covered with wax or “wool” made from webbing they secrete and others have unique distinguishing features.

Common to all aphids, distinguishing them from all other insects, are a pair of “cornicles” which extend like tailpipes from their abdomen. These can vary in length and color.

Aphids colonize the stems and undersides of plant leaves. Some species, such as the black bean aphid, are quite noticeable because their color stands out from the plant. Others, such as the green peach aphid, are often colored spring green and blend in with young leaves.

Aphids are true bugs. Like all bugs, they live on plant juices by puncturing leaves using a straw-like mouth called a proboscis to suck sap from stems, branches and leaves. In order to obtain enough protein, aphids suck a lot of juice, extract the protein and excrete the concentrated sugar solution that is referred to as “honeydew.” The aphid excrement attracts ants that herd the suckers, protecting them from predators. Honeydew is a growth medium for sooty fungus, which causes necrosis of leaf parts.

Heavy aphid infestations cause leaf curl, wilting, stunting of shoot growth and delay in production of flowers and fruit, as well as a general decline in plant vigor.

Aphid Photo by W. Cranshaw, CSU, Bugwood.org

Aphids are vectors for hundreds of diseases and can quickly cause an epidemic. They transfer viruses, bacteria and fungi from plant to plant.

Aphids are true “bugs,” sucking insects in the order Hemiptera. Most aphid species have a complex life cycle. Many species overwinter as eggs, but during most of the season they are nonsexual and deliver nymphs pathogenically. These nymphs are live-birthed and born pregnant. A single species produces populations that differ depending on the season. For instance, seasonally, when infestations become dense, some populations have wings and colonize new plants by traveling on air currents. Each live-birth generation exists for only 7 to 14 days. If left unchecked, aphid populations rapidly grow to thousands.

SoluNeem is NOT neem oil. A highly concentrated, organic water soluble neem powder, SoluNeem needs no emulsifiers or detergents and can cover 1,000 sq ft with one tsp in one gallon of water OMRI certified organic, SoluNeem leaves no sticky residue while eliminating aphids, thrips, white flies, caterpillars, and more. Use as a foliar spray as well as root drench in irrigation and hydroponics up to the day of harvest with no phytotoxicity.

Sexual populations appear in the fall, resulting in eggs that overwinter. All species have temperature-dependent rates of reproduction. But even at the same temperature, aphids may reproduce at different rates based on nutrition from the host plant.

Most aphids live only in the plant canopy. Root aphids, most commonly the rice root aphid, live in the planting medium and feed on the roots, making early detection and treatment much more difficult.

Indoors, with no predators to keep them in check, aphids can overrun a garden in short order.

Air Filtration: Aphids are airborne for part of their life cycle. Use a 340 micron mesh or filter to keep them out of the grow space. A thrips screen should be used in the garden. It works on aphids as well.

Monitoring: Check the plants regularly for aphids—at least twice weekly when plants are growing rapidly. Most species of aphids cause the greatest damage when temperatures are warm but not hot (65-80°F). Inspect root zones and around the tops of pots for aphids in the media. Shaking a container can dislodge some aphids from bottom of the container. Use this technique to spot occurrence.

Catch infestations early. Once their numbers are high and they have begun to distort and curl leaves, aphids are hard to control because the curled leaves shelter them from insecticides and natural enemies.

Aphids tend to be most prevalent along the upwind edge of the garden and close to other sources of aphids, so make a special effort to check these areas. Many aphid species prefer the undersides of leaves, or tender terminating stalks, so check there.

Aphids usually feed on the underside of leaves or on stems. Colors include black, green and red. Once aphid infestation is identified, investigate its extent, then treat aggressively. Dead aphids leave white remains of their exoskeletons. These are sometimes mistaken for other organisms.

Outdoors, check for evidence of natural enemies such as lady beetles, lace-wings, syrphid fly larvae and the mummified skins of parasitized aphids. Look for disease-killed aphids as well: they may appear off-color, bloated, flattened or moldy. These observations should be considered when evaluating treatment strategies. Substantial numbers of these natural control factors can mean that the aphid population may be reduced rapidly without the need for treatment.

Some species of ants farm aphids, carrying them to fresh grazing areas and protecting them from predators. They collect the honeydew, the concentrated sap excreted by the aphids. If you notice ants in the picture, you will have to control to control the aphids.

Sometimes aphids must be controlled outdoors. Often this can be accomplished by spraying them off with water. Spraying several days apart will knock down the population considerably, reducing plant stress. If aphids remain a problem, consider one of the controls listed in the indoor section. Check for ants: when they are present aphids are much more difficult to control, so they must also be eliminated.

Control over 300 insect species with AzaGuard. Labelled for drench and foliar applications to target pests such as root aphids, fungus gnats, mites and thrips. AzaGuard’s food grade, no residue formula is an ideal solution for your garden. OMRI Listed for organic production.

Indoors and in the greenhouse aphids have an easy life. Without threats from weather and by living in a relatively predator-free area, they don’t suffer losses to these relentless killers. Without the pitfalls they suffer in nature, aphid population growth reaches exponential proportions quickly.

Since the balance of nature isn’t operative indoors, the gardener must intervene before an outbreak has reached epic proportions. There are a lot of choices:

Aphid Parasitoids: Professionals often use parasitoids when there is an outbreak that hasn’t reached epic proportions. Predators are recommended for heavy infestations. However, this may reflect profressionals’ preference for aggressive predators over subtle parasites. The predators spend a portion of their life eating aphids, and close-up their actions can be as vicious and dramatic as an alligator’s. The parasitoids inject an egg into the aphid. The egg hatches and the parasitoid larvae feast inside. Most aphids die within one to two hours of this egg-laying. The body of the aphid undergoes a dramatic change as it becomes a “mummy” changes color and bloats. Each larva emerges as an adult Alien-style from the mummy. Not quite as dramatic, except when the adult crawls out of the corpse, but every bit as effective. The old mummy remains stay on the leaf.

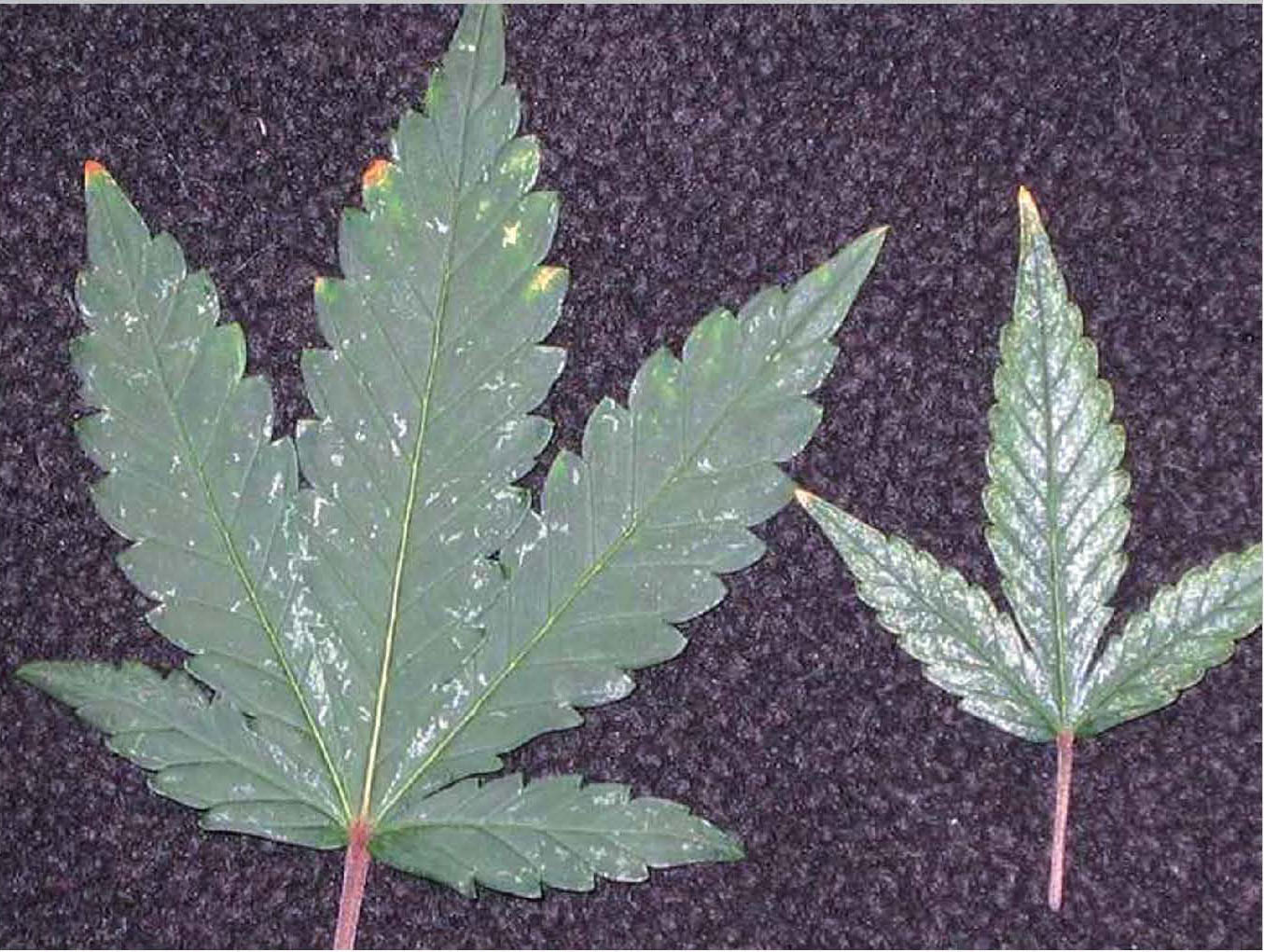

Aphid leaf damage

Among the most important natural enemies are various species of parasitoid wasps (such as Aphidius colemani, Aphidius matricariae and Aphidius ervi) that lay their eggs inside aphids. The generation time of most parasitoid wasps is quite short when the weather is warm, so once mummies begin to appear on the plants, the aphid population is likely to be reduced substantially within a week or two. These wasps are tiny and do not have stingers so they pose no threat to people or pets.

Many predators also feed on aphids. The most well known are the common lady beetle (Hippodamia convergens), green lacewing (Chrysopa rufilabris) and predatory flies (Aphidoletes aphidimyza, Aphidius colemani, Aphelinus abdominalis, Aphidius ervi). Naturally occurring predators work best, especially in small backyards. Commercially available lady beetles may give some temporary control when properly handled, although most of them disperse away from the yard within a few days. They are most effective in protecting large areas rather than small plots, which they are likely to leave in search of dense prey infestations.

Aphids are very susceptible to fungal diseases when it is humid. Whole colonies of aphids can be killed by these pathogens when conditions are right. Look for dead aphids that have turned reddish or brown; they have a fuzzy, shriveled texture unlike the shiny, bloated, tan-colored mummies that form when aphids are parasitized. Make a pesticide by taking these dead aphids, blending them with water (1-3 teaspoons of aphids per quart) and spraying the solution on plants.

Photo by W. Cranshaw, CSU, Bugwood.org

In spring and summer, caterpillars are common outdoors but rare indoors.

Caterpillars are the larval stage of butterflies and moths. They have soft, segmented bodies with a head, thorax and abdomen. The thorax contains three pairs of jointed legs that have hooks, and the abdomen has five pairs of stumpy legs. Caterpillars are often the same color as the leaves so they are hard to spot.

There are many species of caterpillars that feed on cannabis. They have different seasons of activity, rates of growth and developmental strategies that can make them more challenging depending on when and where cannabis is growing.

For example, “budworms” such as the tobacco budworm (Helicoverpa armigera) burrow into flower, often at an early stage, so they are very resistant to treatments that require direct contact. Sometimes called cutworms, armyworms, such as the fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda), feed on foliage in a more conventional way but are known to “cut down” smaller plants early in their development. Finally, tortricid moth larvae are leaf eaters. They curl leaves with silk in order to feed and skeletonize nearby leaves. This also protects them against contact treatments.

Caterpillars that feed on cannabis are generalists. Eggs are laid on the foliage. When they hatch the larvae (caterpillars) feed on the plant and its nearby neighbors. Limiting access to the plants is easier inside a structure or by using row covers. The moths don’t have easy access on the host plant to lay their eggs and the caterpillars are less likely to find access if they are crawling.

It’s a good idea to familiarize yourself with the species that you observe so that you can prevent or treat future infestations.

In addition to this general outline, here are some specifics on the types of caterpillars that commonly infest cannabis:

Cabbage worms: Also called cabbage loopers. The adults are gray-brown moths with a wingspan of about 1.5 inches (4 cm). The caterpillars are green, usually with narrow white stripes along the body, and may grow up to 1.5 inches (3.75 cm) long. A distinctive feature of the cabbage-worm and other loopers are the way they move: arching its back to bring its hind legs forward, then extending its body. Eggs are ridged and dome-shaped and usually laid singly on the undersides of leaves.

Corn borers: The adults are yellow or tan-colored nocturnal moths with wingspans of about 1 inch (2.5 cm). The caterpillars are about 1 inch long; light brown in color with a brown head and spots on each segment. Eggs are white to pale yellow, laid in clusters of 20 to 30 on the undersides of leaves. As their name states, they often bore into the stalks. This destroys the liquid pathways, and all vegetation above the bore hole quickly wilts from dehydration.

Cutworms: The adults are gray to dark brown moths with wingspans of 1.25 to 1.75 inches (3 to 4.5 cm). The caterpillars grow to 1 to 1.5 inches (2.5 to 3.75 cm) long, plump and sturdy, ranging in color from brown to pink, green, gray and black. Eggs vary widely by species but are usually laid on the stems or the upper sides of leaves.

Leaf eaters: Many different species. The adults are usually moths, varying widely in color and with wingspans ranging from 1 to 1.75 inches (3 to 4.5 cm). The caterpillars are usually green but sometimes range from gray to brown, and are up to 1.5 inches (3.75 cm) long. Some leaf eaters are “wooly bear” caterpillars, their bodies covered with long hairs that look much like fur. The eggs may be found anywhere on the plant, depending on the species.

Photo by W. Cranshaw, Bugwood.org

Some caterpillars eat leaves. Others bore into the stem and eat the pith, the stem’s soft inner tissue. Cutworms feed at night and spend the day in shallow burrows near the plants. Some caterpillars pupate in cocoons in the foliage, others move to the soil to pupate underground.

Caterpillars eat both leaves and the soft stems. Borers pierce the stem and eat the soft inner tissue. The branches and leaves above the caterpillar wilt, since they receive no water or nutrients. If it is a main stem, the whole plant dies. If it is a side stem, only that branch succumbs. In addition to the direct damage they cause, caterpillars leave behind damaged tissues that are more vulnerable to infections, especially gray mold.

Caterpillars are voracious eating machines and can savage plants very quickly. They chew continuously to support their high growth rate. Caterpillars can destroy a tray of seedlings overnight.

There are hundreds of species of caterpillar that attack cannabis. They vary widely in size, color, lifestyle and feeding habits. You’ll know leaf-eaters and cabbage worms by the large holes that they leave in the plants’ leaves. The size of the holes indicates caterpillar damage and not that of smaller pests. Cabbage worms also infest buds: a bud that turns brown and wilts may house a cabbage worm consuming it from within.

Cutworms are perhaps the most obvious of all caterpillars: Plants damaged by cutworms are literally chewed through at the soil line, causing the plant to topple. Seedlings and young plants are completely consumed.

Corn borers attack mature plants—they need a stem large enough to hold their bodies. They lay eggs in clusters on the leaves. After hatching, they eat the leaves around the eggs for two weeks to a month, leaving close clusters of tiny holes. To catch borers early, look for these small holes. Later in the season look for small holes in the plant stalks, possibly covered with thin silky webbing. After borers have been at work for a while, they sometimes cause the stalk to develop “fusiform galls.” These are bulges in the plants’ stalks that widen in the middle and taper at both ends. The borers may leave visible trails on the stalks leading to the galls.

Reproduction rate and life cycle: the moths and butterflies lay one or two batches of eggs each year, though some species may produce up to six generations per year in warm climates. Each female lays several hundred eggs. Depending on the species, they mate in spring to early summer, and the caterpillars emerge in the early summer to fall. They feed until they are ready to enter the pupal stage, when they spin cocoons or dig burrows and hibernate until they emerge as adult moths. Those species that emerge in late summer and fall often overwinter as caterpillars; emerging in early spring to begin feeding again (this is especially common with cutworm species).

In general, butterflies and moths reproduce slowly compared to many pests, but they have large appetites and a single caterpillar can cause a lot of damage.

Because caterpillars vary so widely in their habits, the prevention methods vary widely as well. Planting indoors all but eliminates caterpillars. If you do plant outdoors, keep seedlings indoors as long as possible before transplanting, to prevent caterpillars from wiping them out. Clear the garden of weeds, grasses and plant debris throughout the year, but especially at the end of the growing season. Use electric “bug zappers” with blue or ultraviolet light to attract and destroy nocturnal moths. Tilling before planting brings caterpillars to the surface where they are eaten by birds and other predators.

Use netting or screening to cover outdoor plants. Make sure the screen is small enough to prevent moths from dropping eggs.

Cabbage worms: Use row covers in spring, when the adult moths breed, to prevent them from laying eggs on the plants.

Corn borers: Destroy stalks and other plant debris after harvest.

Cutworms: Plant seedlings as large as possible. Turn the upper 2 inches of soil two weeks before planting and destroy any larvae you find. Put a “cutworm barrier” around each seedling. Easy to make is a metal can with top and bottom removed. Place it around the seedling so it goes at least 1 inch (2.5 cm) into the soil and 4 inches (10 cm) above the soil.

Garlic: Repels egg-laying moths.

Leaf-eaters: Use row covers to block egg-laying adults. Wrap stems with aluminum foil above and below major branches and apply a layer of Tanglefoot or similar stick-um to the foil. These barriers block caterpillars moving along the stems. Turn the soil before planting, especially in the spring, to destroy overwintering larvae and pupae.

Quite a few nontoxic and least-toxic methods can be used to eliminate caterpillars.

Special note on stem borers: If you do not control stem borers quickly, your yield will be greatly decreased or even nonexistent. Before they bore into the stalk, you can eliminate them using the same techniques as for caterpillars.

It is a different story once they are situated in the stem’s enclosure. Sometimes you can yank the borers right out of the holes they’ve chewed. Another method is to bore a hole in the stem above the borer and inject one of the recommended caterpillar insecticides into the stem using either a syringe or an eye-dropper.

Deer populations vary widely, both geographically and by habitat. They favor light forest and grasslands near forested areas and dislike getting more than a few hundred yards from cover. Gardens in suburban areas built near forest often have problems with grazing deer. Garden plots set up in wild or rural areas are very likely to be visited by deer if the habitat supports them.

Deer are grazers with graceful bodies, thin legs and long necks. They vary greatly in size depending on species, age and sex, but they usually fall between 4 feet and 6 feet (1.2 and 1.8 m) long and weigh 80 to 220 pounds (35 to 100 kg). Deer in southern areas are smaller than northern deer. The males carry antlers beginning in late summer, shedding them usually in very late winter through spring. Northern deer are heavier than southern deer.

Deer emerge from forest cover at night to browse on plants but flee quickly when approached. They have excellent senses so most of the time the gardener knows them only by their tracks and the damage they leave. However, deer that have become accustomed, or attenuated to humans often graze during the day.

Deer prefer fresh leaves, fruit and other rich plant matter. In the marijuana garden they strip plants of leaves and buds and even tear up small plants and eat them whole.

Marijuana evolved cannabinoids in part as protection against herbivores. Most mammals find the leaves and flowers unpleasant. Deer are among the few exceptions. Deer may be attracted to your garden simply because it’s a food supply that most other herbivores leave alone. They prefer young, tender plants. As marijuana plants mature and cannabinoid levels increase, deer find the plants less palatable.

Deer damage is fairly easy to spot. They lack upper incisor teeth so a deer takes hold of leaves with its lips and lower teeth, then tears them off. This creates ragged browse damage, very different from the neatly clipped leaves left by rodents. Also, look for deer tracks and droppings near the garden.

Reproduction rate and life cycle: Deer follow a normal mammalian life cycle. They mate in the late fall through midwinter, and the female gives birth to one or sometimes two fawns in late spring to early summer. Deer usually mature in one to two years and live for 10 to 20 years if not killed by predators or disease, usually about five years in the wild. Their life span in the wild is usually fewer than five years.

Naturally, deer pose little threat to plants grown indoors. Any outdoor garden near deer habitat is vulnerable, however.

The only effective option to prevent deer damage is to keep them away from the plants. There are two main ways of doing this: repellents and fences. Repellents are less expensive and may be the only option if discretion is important. But fencing is more certain when it is practical.

Deer find the odors of garlic, capsaicin and rotten eggs offensive, and commercial repellents containing these ingredients are available under several brands. Other materials also repel deer by smell:

If you are not certain that a repellent is safe for use on food plants, then surround the marijuana plants with other plants that you don’t plan to eat. Replace the repellent according the manufacturer’s instructions, or every few days for the other scent repellents listed above.

Scent isn’t the only way to repel deer. Anything that startles or frightens them is effective. Buy several home motion detectors at a hardware store and set them up in a perimeter around the grow site. Depending on the resources at the site, motion detectors can be rigged to trigger high-pressure water sprinklers (these are sold as “scarecrow sprinklers”), bright lights, battery-powered radios or ultrasonic noise when a deer approaches. Remember to set up lights to point away from the plants.

A final word about repellents: Deer become attenuated to most sounds, sights or smells. Once they realize that the repellent isn’t harming them, they learn to ignore it. To reduce attenuation, change the repellent regularly, not just from one brand to another, but by using different ingredients and/or methods. Combining methods is also useful. For example, setting up an odor repellent and a scarecrow sprinkler together.

Even with repellents, the chance of predation grows with water and food stress. Deer will choose sources where there is less stress. As food or water become stressed, deer will take more risks [to find it]. In that case the only way to protect the garden is to fence it.

Fencing must be constructed with the abilities and habits of deer in mind. A deer can jump any fence less than 8 feet (2.4 m) high, if it can get close enough. Fences must also be built tight to the ground, or deer can slip under them. One alternative to an 8-foot fence is an electrified fence. Deer prefer to slip through a barrier rather than jump over it if that looks possible. So a standard electric fence built from two or three strands of 20-gauge smooth wire on insulated posts often deters them. Once they try to slip between the strands and get shocked, they generally keep several feet away from the fence—too far for them to jump it. A variant called a “Minnesota fence” actually uses an attractive bait such as peanut butter to get the deer to lick the fence or a foil tag attached to the fence. The deer gets a mild shock and avoids the fence completely after that.

There is no practical means of controlling deer, in the sense of eradicating them, and this would not be a good option even if there were such a means. The outdoor marijuana gardener should leave the deer’s natural predators (mainly coyotes and wild dogs) alone, as these provide some check on the deer population. However, aside from that, prevention is your best choice.

Perimeter fencing is one method of controlling deer invasions.

Fungus gnat

Fungus gnats are common indoors. They are found outdoors in moist warm areas.

Fungus gnats are flies about 3-4 mm in size and dark grayish black. They have a slender build with delicate long legs, a small round head with long antenna and two long wings. They look similar to a mosquito. The maggots are clear to creamy white in color with a shiny black head and can be up to .25 inch (6 mm) long but are usually smaller. The most common ones, found in gardens and house plants are in the Bradysia species, known as dark winged fungus gnats.

Adults fly close to the soil level and through the plant lower canopy. Fungus gnat larvae live at the root level, usually from 1 to 3 inches (2.5 to 7.5 cm) below the soil line. In shallow containers the maggots may be found wiggling in the drain tray after watering.

Fungus gnats’ maggots eat roots, root hairs and organic matter, which weakens the plant. They tunnel into the plant stem, causing the stem to collapse. The maggots are also vectors for various diseases such as Pythium, Fusarium and Verticillium. Adult fungus gnats do not have mouths. The live only to reproduce.

Outdoors, adults and larvae live in moist, shady areas. The adults hover near the soil surface. The larvae live at the root level. Fungus gnat larvae attack plant roots growing in planting medium, rock wool and other planting media. Indoors, females are attracted to moist planting mix, including rockwool.

Fungus gnat larvae

Reproduction rate and life cycle: The adult females lay eggs at the surface of moist soil, near the plant stem. The larvae hatch out in four to ten days, depending on temperature, and feed off fungus and plant matter (including plant roots), then pupate in the soil and emerge as adults. The total time from egg to reproductive adult is about four weeks, and each female may lay several hundred eggs in small batches. Indoors, they breed continuously throughout the year and reproduce very rapidly.

Fungus gnats, particularly those in the genus Bradysia, are very common pests to encounter. Despite their common name, larvae feed on both fungal and plant matter, and they can be vectors for several plant pathogens, including Fusarium. Fungus Gnats reproduce well in moist, organically rich substrates, and can sometimes be a sign of poor irrigation management, especially over watering.

If plants are outdoors, check the soil for adult gnats or larvae before bringing them indoors.

Prevent indoor entry of gnats by keeping screens on all open windows. Place a barrier over the soil so the gnats have no place to lay their eggs. A piece of cloth, cardboard or a layer of sand all work.

Fungus gnats need moist soil near the surface to reproduce. Avoid overwatering soil and let the soil dry between watering as much as the plants will tolerate (usually to a depth of about 1 inch (2-3 cm). A layer of light, well-draining planting media ingredients such as sand, vermiculite, perlite, or diatomaceous earth at the top helps with this. This disrupts the larval gnats’ food supply and makes it difficult for an infestation to take hold.

In hydroponic gardens, fungus gnats can be an issue for rockwool specifically. The green algae that likes to grow on rockwool that’s exposed to light and moisture is an environment the gnats thrive in. To prevent its culture on your rockwool or any other media, cover it to remove the light. The algae need light to live. No algae, fewer gnats. Hydrogen peroxide at a 10-20% dilution can be used to clean the surface areas. A drench at 1% can be fed to infected root zones in dire measures.

Keeping the top of the growing substrate dry decreases the attraction and subsequent incidence of fungus gnats. This may simply require a strategic watering plan. Predatory soil mites like Hypoaspis miles or Stratiolaelaps scimitus are preventive biocontrol agents that can be established in the crop. The insect-killing fungus Beauveria bassiana can also be applied to growing substrates to help control populations.

Gopher

Gophers are a very occasional problem in the garden. They are found mainly in the central and western United States, in Florida, and in Mexico.

Gophers are medium-size rodents ranging from about 5 to nearly 14 inches (13 to 36 cm) long (not including tail). Their fur is very fine and ranges in color from nearly black to pale brown. The forepaws have strong claws. The head is small and flattened, with small ears and eyes and very prominent incisor teeth.

Gophers tunnel underneath gardens and lawns.

Gophers feed on plants in three ways:

Gophers are prey to badgers, which eat them. Badgers can cause considerable damage when digging for their food.

When gophers are suspected, the first task is to make sure that they aren’t moles. Moles cause little direct damage to gardens, and as a result they’re seldom worth the trouble to eradicate. It is rare to see either one on the surface, so the best way to distinguish them is by observing the signs they leave behind.

First, check their diggings: A molehill is usually a rough cone with a hole or an earthen “plug” near the center. A gopher mound is more fan-shaped, with the hole or plug near one edge.

Next, look for damage. Moles generally cause very little damage. Gophers may chew the plants’ roots, causing them to wilt and making it possible to pull them up with just a slight tug. If plants are chewed off completely at the soil line, or completely gone, roots and all, then chances are good that there is a gopher problem.

Reproduction rate and life cycle: Gophers mate once a year, in the spring, and produce a litter of up to five young in late spring to early summer. They live for up to 12 years.

Containers, indoor gardening and hydroponic systems offer complete protection against gophers. In the field minimize weeds, as they are likely to attract gophers. If you are planting directly in the soil, line the planting hole on the bottom and sides with hardware cloth. Anecdotal evidence suggests a border of oleander plants around your garden repels gophers. Any of several commercial gopher repellents (most include castor oil, garlic or capsaicin) placed in the mouth of the mound may drive them off.

It is best to try repellents first, as they are by far the easiest way to deal with gophers. However, sometimes the only solution is to eliminate them.

The simplest means of exterminating gophers is fumigation. However, this will poison the soil for marijuana cultivation so it should not be used. Do not use this method. Commercial fumigants are generally paper or cardboard cartridges filled with charcoal and potassium nitrate.

Carbon dioxide (CO2) gassing is a safer method of fumigation. The simplest way of getting it into the gopher’s tunnel is either direct from a CO2 tank (place the delivery hose in the tunnel opening) or as dry ice. Drop 8 to 16 ounces (225 to 450 grams) of dry ice into the tunnel, or deliver a similar amount of CO2 from the tank. Rather than poisoning, CO2 suffocates the pests.

Fumigation is not always effective. If not, then trapping is the only way. Suitable traps are available at garden shops, both box traps and lethal forms.

Water in and wipe out damaging insects with SNS-209™ Organic Systemic Pest Control. Made from 100% pure botanical extracts that are water soluble and food grade, it is FIFRA section 25(b) exempt.

Leaf miners

Leaf miners are not common in indoor marijuana gardens. Outdoors leaves are occasionally attacked, but they are not usually a threat to the plant or yield. The three most common are in the genus Liriomyza, commonly known as the pea leaf miner, the American leaf miner and the vegetable leaf miner.

Leaf miners in cannabis are usually the larval form of various species of flies, though a few species of moths and beetles also produce leaf-mining larvae. These larvae are very small maggots—seldom more than 3 mm long—ranging in color from white to pale green. The adult flies resemble tiny houseflies, about 2 mm long.

Leaf miner flies get their name from their larvae, which exist between the top and bottom margins of a leaf, feeding on the interior tissue. Adults reproduce rapidly and are prolific.

Leaf miners are found in the leaves, under the surface in the tissue. These flies are common pests of ornamental plants like Gerbera daisies and Chrysanthemums as well as vegetable crops such as Cucumber. The presence of these plants allows a nearby population to infect cannabis.

These little creatures are a pain to get rid of. While the maggots eat and dig squiggly lines into your leaves, the adults take small dot shaped meals from the leaves. No hole is left behind, but the plant cells are damaged. The adults lay eggs into the remaining tissue. When the eggs hatch, the larvae feed off the leaves. They look like carved scribble lines. The scribble lines get bigger as the maggots grow. They chew a hole to emerge to pupate. This occurs in the soil. Once they emerge they repeat this cycle creating a larger infestation.

Leaf miners wound the leaves and open them to infection by bacteria and fungi. Leaf damage reduces yields. When the females dig to lay eggs, plants secrete a sap that attracts ants and flies, thus inviting more infestations and problems.

Leaf miner maggots eat their way through leaves creating tunnels. Adults puncture the leaf to feed and oviposit. This damage is milder than the damage done by the maggot.

There are many varieties of leaf miners, but it requires an expert to distinguish between species by the characteristic appearance of their tunnels. They have evolved their unique form of attack as a means of avoiding predators and chemicals harmful to them such as THC.

Leaf miners

Reproduction rate and life cycle: Female leaf miners implant eggs in leaves—one at a time but often in close batches. Females lay 200-300 eggs depending on species. Eggs hatch in two to six days, and larvae begin tunneling. In about a week the maggots exit the leaf to pupate for about a week. The pupa is reddish brown, about 1.5mm. The pupae develop into adults and the cycle repeats. Expect two to six generations per year outdoors, but indoors a single generation can take as little as a month, and they reproduce year-round. In warm tempurature the cycle can be as little as 15 days, or up to 25 days in cooler weather. They are rare outdoors during cold seasons.

Outdoors, insect repellent plants such as lamb’s quarter, columbine or velvet leaf can be planted near cannabis to deter the leaf miners.

When it comes to control, the adults should not be the main target because most adults have already mated and laid their eggs.

Leaf miner larvae are tricky to deal with, however, as they cannot always be directly contacted with spray applications of contact-kill products, and the puparia are often resistant to the chemistry.

Biocontrol agents including the parasitic wasps Diglyphus isaea or Dacnusa sibirica are common commercial choices in farms, and naturalized populations may already be associated with leaf miner populations already present.

Remove the lower canopy of cannabis plants because these flies prefer lower leaves. You can also use trap plants such as cucumber, soy bean, peas, melons, and various Solanaceae plants.

If only a few leaves are affected, remove and discard them. Naturally occurring parasitic wasps usually help control the population.

Mealybugs and scale occasionally attack cannabis.

These pests are true bugs of the insect order Hemiptera and use their proboscis, a straw-like mouth to pierce plants and suck their juices. Mealybugs and scales are closely related to one another but take their names from their appearance. Mealybugs are named for the white, “mealy” wax that covers their bodies. On plants they look like tiny puffs of cotton, usually in crevices and joints between branches. The adult female insects beneath the wax are 0.1 to 0.2 inch (2 to 4 mm) long, with flat, oval, segmented bodies. Males are tiny flying insects that do not have the females’ waxy covers.

Adult female scales produce hard shells that resemble tiny “scales” or bumps on the stems and leaves of the plants. Scales vary widely within this general model: from round to oval in shape, from white to dark brown in color and from 0.1 to 0.5 inch (3 to 15 mm) in diameter. As with mealybugs, adult male scales resemble tiny flies.

Female mealybugs plunk themselves at the nodes. Scales are found on leaf surfaces (especially the undersides), on stems and in crevices. Occasionally, scales or mealybugs colonize the stem right at the soil level, where the stem joins the roots. Mealybugs and other scale insects share several common traits. Adult males are very rarely present. Females produce hundreds of eggs over a lifetime. Once they set down, they remain in a single place for life. They exude honeydew, concentrated plant sap, just like aphids. This promotes the growth of sooty mold. Armored scales have a hard exoskeleton structure for protection that soft scales lack. Instead, soft scales and mealybugs produce copious amounts of wax for protection. This makes them somewhat resistant to the application of some sprayed treatment compounds.

Female scales and mealybugs feed on plant sap. The males, on the other hand, are short-lived, and as adults, they do not feed at all. They live only to mate with the females. Some species have developed a symbiotic relationship with ants similar to that of aphids. Ants protect and herd them to collect the honeydew, concentrated sugars that they exude as waste. If there are no ants to eat it, it’s quickly colonized by sooty mold. Plants are weakened by the insects’ leech-like action on their vital juices, and the honeydew droppings create mold infections on the stems and leaves. Scales and mealybugs are often vectors for plant diseases.

Mealybugs are considered a specialized scale. Both are in the same order as aphids and whiteflies, and are true bugs in the biological sense. Like all true bugs, they have specialized probing and sucking mouthparts, the proboscis that they use to drain plant juices.

Female scales and mealybugs do not move much as adults. They attach themselves to the plant and produce a protective layer to ward off predators while they suck the plant juices. Mealybugs cover themselves with a web of cottony wax that some potential predators avoid. Scales produce hard shells that armor them against their enemies.

Reproduction rate and life cycle: The overall life cycle is the same for both mealybugs and scales. The females produce 200 to 1,000 tiny eggs that they shelter either on or beneath their bodies. When the eggs hatch (in one to four weeks), the very small (less than 1 mm) nymphs spread out over the plant and begin to feed. In a few weeks they develop into either winged males or stationary, shelled females. The entire generation takes one to two months. Depending on the species, they produce one to six generations in a year.

Mealybugs are relatively easy to eliminate on marijuana plants because the plant’s structure does not offer easy places for them to hide and protect themselves.

Because of their slow rate of reproduction, they rarely cause a threat to the garden indoors or out.

Hand-wipe with sponge or cotton swab. Mealybugs tend to locate in plant crevices and other hard-to-get-to spots. A cotton swab moistened with isopropyl alcohol is an ideal tool for reaching them.

Mealybug life cycle

Spider mites congregating

The term “mite” encompasses thousands of different arthropod species, most of them well under one millimeter in length — roughly the size of the head of a pin — and the largest mite common to cannabis is roughly half that size.

Three types of mite account for almost all infestations of cannabis: Broad mites, Hemp Russet Mites and Two-Spotted Spider Mites. They range from difficult to impossible to spot without magnification and reproduce rapidly. This means, with the smaller species particularly, the damage is what you see first and by then there are already multiple generations of mites inhabiting and destroying your plant. It’s more or less impossible to control a full-blown mite population bloom, so it’s especially crucial to maintain preventative conditions and regularly inspect plants so action can be taken as early as possible if mites do appear.

When it comes to greenhouse grows the primary source of mites is infected clones, so in addition to proper sanitation, great care must be taken when sourcing new genetics. Biocontrol of a mite infestation needs to be established before flowering, otherwise the reduced light times will cause a clustering response in the mites, rendering predatory mites all but useless. If mites are detected early enough, before too much damage has been done to the affected plants, their numbers can be effectively thinned by spraying plants with water, but additional control methods are required to fully eliminate them.

The broad mite or, Polyphagotarsonemus Latus, is a new pest in cannabis gardens and sightings are becoming more common.

The most notable thing about the broad mite’s appearance is its diminutive size. They are so small that a 60x loop or stronger is recommended to properly identify them. With the naked eye you will only notice a large infestation, clusters of egg sites and the telltale broad mite damage. Up close the broad mite has a structure and appearance similar to larger mite species. Its coloration can vary, but often it looks like a pale yellow or clear dewdrop with tiny legs. Broad mites have a large cephelathorax, two pairs of small front legs, one pair in the middle of its body, and a wispy pair of back legs; which are more pronounced in the smaller males. Under a microscope they have a medium-size head with a definitive mandible structure. Broad mite eggs are translucent, round and with white spots. These are actually tuffs of spine-like hair, but appear as spots. They are 0.08mm in diameter.

To target Spider Mites, Clover Mites, Broad Mites and Cyclamen Mites, Neoseiulus Californicus from Biotactics, is a hearty and effective Type II predator that will lay one egg for every 4-6 units of food (spider mite adult/ nymph/egg). Effective on almost every plant from roses to strawberries to cannabis and alfalfa.

Broad mites lay eggs on the undersides of leaves. They prefer newer growth and the crevices of the cannabis plants. Always inspect the damaged growth areas with magnification, paying close attention to the ribbing of the veins on the underside of the leaves.

Broad mites cause two types of damage that are great clues for identifying them. The first is often “stipling,” which is a pattern of yellow dots on the leaves. These are the tiny feeding sites from the infestation. Often stipling is inconspicuous, but the leaves turn darker. As time passes after the initial wounding the sites become yellow to gray or even necrotic. These yellow speckled leaves as well as a twisting and/or yellowing of new growth are the second signs of damage. This is a result of the mites feeding. If you see these two signs in a garden, use a 60x loop to look for broad mites.

Mites are vectors for infections, but their main damage is the sucking out of nutrients from the plants’ leaves, which interferes with photosynthesis. Draining liquids and nutrients from the leaves slows down the plants’ growth. This, along with vectors they can carry, and excrement and secretions lead to telltale damage in new growth.

Prevention of broad mites can be tricky. It’s difficult to surmise where they came from in many instances. Often they come in the wind, infected plant material, or are deposited by animals. One of the most likely sources of infection is importing infected clones. For this reason, many growers start plants only from seed. A good integrated pest management program is always recommended. A periodic spray with an herbal pesticide is a good start.

A product called Nuke Em produced by flying skull is effective at eradicating broad mites. It contains potassium sorbate and yeasts.

Debug, a product described in aphid treatment and control, can be used to combat broad mites. Neem oil can be effective, but this concentrated formulation is much more effective.

Azamax and other azadirachtin-concentrated amendments are also effective and allowed in most regulated states.

Attack Spider mites, Clover Mites, Broad Mites, and Bank’s Grass Mites in the vegetative state or bloom state with Neoseiulus Fallacis, a cousin of Californicus. From Biotactics, this is hearty and aggressive predatory mite and will overwinter in the soil and cover crop in hibernation and is used on tens of thousand of acres of coastal California strawberry farms and min farms in Southern Oregon.

Adult russet mite

Aculops cannabicola first appeared in Serbia and Hungary in the 1960s. This cannabis specific mite is still not common but is spreading quickly through the country.

They are smaller than conventional spider mites but larger than the broad mite so a 30x or larger magnification may be necessary to fully identify an infestation. They are built slightly differently than the spider or broad mites as well, having an elongated body, often described as carrot shaped. They have a clear to milky color makes them almost look like larvae of some other pest. Russet mites have only four legs instead of eight like other mites.

Like the other mites, they will be located on the undersides of leaves. Russet mites work their way up plants, preferring the younger soft terminal leaves, so they are found on leaves just above damaged leaves and stems.

The mites suck precious sap and nutrients from the leaves and petioles of the plant. This causes a type of stippling that often turns orange or yellow “russeting.” Soon the infected leaves die and drop off from the damage. As the colony progresses up the plant it inevitably weakens and dies.

All mite populations have the potential to increase numbers quickly when environmental conditions are favorable. For the three species of mites listed in this book that mostly pertains to rises in temperature. As air temperature reaches favorable conditions for cannabis growth, it also increases the mites’ rates of metabolism and reproduction. A space that peaks at 85°F decreases the mites’ time to sexual maturity as well as their gestation time. They do not multiply quickly compared to other mites.

Sometimes a clean-out and a replacement crop is better than fighting them as they multiply logarithmically.

To treat Spider Mites and Russet Mites, apply Galendromus Occidentalis during the vegetative Bloom stage. This Western Predatory mite can withstand hot arid summers and can be applied with crop dusters and drones for precise application.

The russet mite works its way up plants from the bottom. So remove damaged leaves. Quarantine and treat the infected plant.

Russet mite damage

The damage mites can cause in a hot grow room can easily be so substantial during the first three weeks of flowering that starting over in a clean room with new plants maybe an economically better option. Russet mites have been reported to be particularly resistant to neem and other horticultural oils so this throw-’em-out and start-over mentality may prove doubly in order instead of a pitched chemical battle.

In hemp fields the introduction of predatory mites can prove effective. Using biological control measures outdoors can have it’s issues, but if its timed right and multiple applications of predatory mites are used in intervals of four to seven days, the damage can be minimized enough to have a successful yield. Russet mites remove cell content from the leaves with piercing, sucking mouth parts.

Azadiractin

Citric acid

Herbal oils: Cinnamon, Clove, Geranium, Peppermint, Rosemary, Thyme

Potassium salts of fatty acids

Sulfur: Micronized sulfur applied as directed.

Spider mite Photo by Biotactics

Spider mites are very common. They are the most serious pests in the cannabis garden.

Spider mites are barely visible with the naked eye since they are only 0.06 inch (1.5 mm) long. They are arachnids (relatives of spiders), and like other arachnids, they have four pairs of legs and no antennae. Like spiders, they have two body segments. Their colors range from red, brown and black to yellow and green depending on the species and the time of year. Spider mites are so tiny though that most of these details are visible only with a magnifier. Spider mites make silk, hence the name spider mite.

The two-spotted spider mite, the spider mite most likely to attack cannabis gardens, has two dark spots visible on its back when it is an adult.

They live on the plants, mostly on the underside the leaves, but can be found on the buds. They can also be found moving along their silvery webbing, from leaf to leaf and even plant to plant.

Spider mites pierce the surface of the leaves and then suck the liquids from cells. These punctures appear on the leaves as tiny yellow/brown spots surrounded by yellowing leaf.

Identify infestation by tiny spots on the leaves. They can be seen as colored dots on the leaf undersides. As the population grows they produce webbing that the mites use as a protective shield from predators, a nursery for their eggs and a pedestrian bridge between branches or plants.

Spider mites pierce cells and suck their liquids. They are more of a threat than most pests because of their high rate of reproduction.

Spider mites are by far the most fearsome of all plant pests. They suck plant juices, weakening the plants. Spider mites multiply quickly. They are most active in warmer climates than cold ones

Reproduction rate and life cycle: Newly hatched mites are 3:1 female: male, and each female lays up to 200 eggs, 1 to 5 per day, as an adult. This life cycle can repeat as often as every eight days in warm, dry conditions such as a grow room. Spider mites spread through human transport as well as by wind in outdoor gardens.

Targeting Spotted Spider Mites and Pacific Mites, Mesoseiulus Longipes is the rarest predatory mite species in the world and is perfect for high elevation growing as well as dry desert areas, and is available from Biotactics.

1) Spider mites and mite eggs on a leaf; 2) Spider mite webbing; 3) Mites congregating; 4) Spider mite damage; All photos by W. Cranshaw, CSU, Bugwood.org

Because of their rate of reproduction and the short time from egg to sexual maturity, a spider mite population can explode with shocking speed.

Almost all spider mite infestations enter the garden on an infested plant, through the ventilation system or by gardeners who carry the hitchhikers into the garden. Use a fine dust filter (at least 300 microns) in the ventilation system, and never enter the grow space wearing clothing that has recently been outdoors, especially in a garden. Best practice is to keep pets out as well.

Use Persimilis, the first predatory mite ever used as a pest management product, to attack Two Spotted Spider Mites and Pacific Spider Mites in both Vegetative and Bloom State. These Type I predators only have one prey and can eat 35 food unites (a spider mite egg or adult) per day while laying 4-7 of their own eggs. They are extremely ravenous but need 70% relative humidity for their eggs to hatch, making them a great predator for hot spots with larger infestation problems. Find them at Biotactics.

Neem oil is often used as a preventive, but always look out for webbing and for the yellow-brown spots mites leave when feeding. Infected mother plants transmit mites on their clones, so it is especially important to watch for mites in a mother room. When you spot mite symptoms take action immediately.

Growing from seed in an indoor environment is a great start to prevention in an indoor grow space.

Don’t introduce plants from other spaces or quarantine new plants for several weeks.

Spider mites thrive in dry climates. Increasing humidity in the vegetative and early flowering stages can slow population increase.

Predator mites: There are many varieties of predator mites. Get those best suited to the environment of the garden. Apply predator mites at the earliest sign of infestation. Most predator species reproduce faster than spider mites, but if the mites get a good head start, the predator population can never catch up. Even in optimal conditions, control with predator mites is very difficult. Four effective species are Phytoseiulus persimilis, Amblyseius swirskii, Amblyseius fallacis and N. californicus.

In warm indoor gardens, things can get out of hand quickly. If the infestation is noticed on a new crop, it may be more advantageous to cull that crop and clean the grow room with a light bleach solution. Additional measures include waiting 10 or more days and recleaning in case of a substantial outbreak. When treating plants, it is always advisable to remove lower leaves that contain large amounts of eggs. This along with repetitive spraying may be necessary.

Spider mite infected cola

Moles are common in temperate rural areas, less so in cities and suburbs. They may gravitate to outdoor cannabis fields because cultivation loosens the soil and makes it more hospitable to the insects that moles eat.

Moles are burrowing mammals about 5 to 7 inches long, weighing 3 to 4 ounces. They have soft dark fur, very small eyes, pointed snouts and strong digging claws on their front feet. Moles seldom appear on the surface, though. The gardener usually notices their burrows instead.

Moles build tunnel complexes in rich soil. They eat insects and earthworms and therefore favor moist soils with a lot of soil-dwelling insect life.

Moles seldom damage plants directly. However, their tunnels and mounds may allow plant roots to become dry, and their holes create a hazard for careless walkers.

The most important consideration in dealing with moles is distinguishing them from gophers, which are much more destructive. The marijuana farmer has little to worry about from moles, once she or he is sure they are moles. The clearest distinction between them and gophers is the shape of their diggings: a molehill tends to be a rough cone with a hole or an earthen “plug” near the center. A gopher mound is more fan-shaped, with the hole or plug near the narrow end.

Reproduction rate and life cycle: Moles generally have one litter of two to five pups per year, in mid to late spring. Except for the spring breeding period, they tend to be solitary and highly territorial. They fight other moles even to the death if one invades another’s tunnel system.

If you are planting directly in the soil, line the planting hole on the bottom and sides with hardware cloth. Repellents may work in outdoor gardens. A number of manufacturers sell devices that they claim repel moles by sending irritating vibrations through the soil. However there is some controversy over whether they work consistently. Odor repellents such as predator urine may be more effective, but the best-attested repellent is castor oil, sold in various brand-name formulations.

If moles aren’t causing root damage then there is really no need to get rid of them. However, if it is necessary to rid the garden of moles then the methods are the same as for gophers: fumigation or trapping. The commercial fumigant cartridges sold for gophers also work against moles, as does carbon dioxide from dry ice or a tank. Garden supply shops sell many kinds of mole traps, both the live-trap and lethal kind.

Rats are not common pests in marijuana gardens, but they sometimes kill plants by gnawing or digging. They are a very environment-specific problem, as they view cannabis as a target of opportunity.

Rats are rodents ranging from 10 to 16 inches (25 to 40 cm) in length, not including their long tails. They weigh 6 to 12 ounces (170 to 340 grams) and have dark fur ranging from brown to black. Their heads are long and taper to a snout with long whiskers, and their ears are rounded and prominent.

Rats are common wherever humans live, although they are not always visible. Some rats live in the wild, feasting on insects, other small animals, nuts, fruits and nature’s detritus. They lair in burrows, walls, piles of trash, dense brush, attics—wherever they can build a secure nest.

Marijuana is not a primary food source for rats. In fact, they may not eat it at all. Instead, rats like to chew the woody stalks of plants, cutting the plants down. The rats usually simply leave it at that, not eating the rest of the plant. A rat’s teeth grow constantly throughout its life, and this gnawing behavior is instinctive to keep the teeth from getting too long.

Rats do not look for marijuana plants; they go after them only if they’re convenient. So rats are a problem for the marijuana garden only when the grow site is close to something that they do like to eat. Gardens are at risk for damage by rats near cornfields, orchards, food warehouses, areas with nuts or berries growing wild and similar places. Food at campsites draws rats close to the garden, so secure all food and destroy or remove all food scraps.

Reproduction and life cycle: Rats are prolific breeders that breed year-round if they have adequate food and a warm place to keep their young. Each female can produce four to nine litters a year (of which anywhere from 12 to 60 young live to adulthood). They adjust their population automatically to the local food supply.

An ounce of prevention is worth many pounds of cure with rats. They do their damage in a matter of minutes, and a single rat can destroy several plants in one night. By the time you know you have a rat problem, it is often too late. Humans have been fighting rats for thousands of years, and if numbers are any guide, then the rats are at least holding their own.

Minimize the amount of rat tasty food in the area. Clear away brush and trash and plant as far as you can from attractions such as fruit trees or berry bushes. If you know of stray cats in the neighborhood of your garden, put out food to attract them. Rats avoid areas that smell of cats.

Aside from cats, the most effective prevention is a physical barrier to keep the rats away from the plants. Because cannabis isn’t a primary food for rats, they won’t try as hard to get it as they would if they actually liked to eat it.

An effective barrier needs to be at least 18 inches (45 cm) high and have no opening larger than 0.5 inch (12.5 mm). A simple way to meet these requirements is to wrap a tomato cage in chicken wire or hardware cloth and put one of these around each of the plants when you set them out. Another is to buy coarse steel wool (sold in bulk at hardware stores) and wrap it around the stalk of each plant, securing it with twist ties.

Traps and poison provide protection. Hardware and garden stores carry a variety of effective rat traps. Place traps around the plant cage, using an attractive bait such as peanut butter. Once a few rats have been trapped, predators may come to enjoy the carrion, making the area unattractive to the rodents.

Rats have begun to develop resistance to warfarin, the classic anticoagulant “rat poison.” Another problem with this poison is that it can kill predators that eat the dead rats. A newer poison is cholecalciferol (vitamin D3). Another is zinc phosphide. Both are available in various brand-name rodent baits. Place any such poison bait in a tamper-proof bait station.

Slugs and snails occasionally attack outdoor gardens. They are rare indoors.

Slugs range in color from pale gray to tan and grow to as long as 2 inches (5 cm). Their bodies are soft and fleshy, and glisten with a clear slime that they secrete to retain moisture and help their movement. Two small “horns” atop the slug’s head are actually the slug’s eyes. These sense light; slugs have no of sight of objects.

Snails are slugs with shells. They are built almost identically to slugs, except for a coiled shell of calcium carbonate that protects most of a snail’s body. A snail can withdraw completely into its shell when threatened. The shells of common garden snails can reach up to 1.5 inches (3.75 cm) in diameter, and come in various shades of gray, brown, and black, sometimes with markings, depending on the species.

Slugs and snails are found on the leaves and edges of leaves and flowers. During the day they rest in moist cool areas such as under debris or wood.

They eat leaves. Holes in leaves and/or clipped edges of leaves and flowers, accompanied by a silvery, slimy trail, indicate snail or slug damage. A single snail can savage several small plants in one night.

They thrive in moist, dark environments. They hide in mulch, in short and stubby plants, under boards, and in soil, and they avoid sunlight, so they are seldom seen during the day but come out to feast at night.

Banana slug

There is one particular kind of snail that you should leave alone. So-called decollate snails sometimes attack plants, but their main food is other snails and slugs. The fastest way to tell a “good” snail from a plant-eating pest is the shape of the shell: common garden snails usually have round shells that coil in a simple spiral. Most species of decollate snails have cone-shaped shells. If these are the only snails you ever see in your garden, then go ahead and get rid of them, because they eat plants if there is no other food in their habitat. But if you have other snails as well, then the decollate snail is your friend.

Reproduction rate and life cycle: Slugs and snails are hermaphroditic and can fertilize themselves if no mate is available. They lay clutches of 30 to 120 eggs 1 to 2 inches (2.5-5 cm) deep in moist soil. When conditions are suitable (not too dry or too cold), slugs and snails can lay eggs as often as once a month, so their numbers can increase rapidly during damp spring and fall weather.

The best way to prevent and kill snails and slugs is with iron phosphate, sometimes called ferric phosphate. It is completely effective and requires little effort. It comes as a powder or granules and is not harmful to plants, pets or humans. Sprinkle on the ground as directed. Many brands are available.

Diatomaceous earth sprinkled around the base of the stems helps keep out slugs and snails, but it can also hinder beneficial insects.

A number of methods can be used to prevent snail or slug damage. Reduce damage dramatically by watering in the morning instead of the evening. The soil has time to dry out and become less attractive to the pests.

Place copper wire, tape or mesh around the garden or at the base of the plants. Copper shocks the pests and deters them (dimes and quarters work as well). When enclosing the garden or plants with copper, make sure not to trap the snails inside.

Slugs love beer! Bury a container of beer in the garden, leaving it just barely above the ground so they can drink it and drown. Salt causes their bodies to shrivel up.

Predators including firefly larva, toads, frogs, fireflies, snakes, birds and black iridescent beetles like snails. Firefly larvae eat slugs and snails viciously. Snails and slugs can be trapped. Construct a cool moist area for them to retreat to during the heat of the day.

Made from food grade essential oils, Ed Rosenthal’s Zero Tolerance Omri pesticide attacks all soft- bodied insects, repeals infections before they even start and will leave you with products that test clean, since it completely dissolves and leaves no residue.

Thrip infestation Photo by W. Cranshaw, CSU, Bugwood.org

Thrips are not commonly considered pests of marijuana outdoors. However, in greenhouses they can be serious pests.

Thrips are tiny, no more than 0.06 inch (1.5 mm) long, but can still be seen by the naked eye, often compare to a grain of rice. Adults have wings but do not fly well; they jump or fall when startled. The head and body range from yellow to dark brown and even black and white stripes. The larvae are about half the size of adults, lighter in color, and wingless. One of the most common species on cannabis is the onion thrips, (thrips tabaci). Another common species is the western flower thrips (Frankliniella occcidentalis).

Thrips attack the leaves and are usually found on the top surface of the leaf.

Thrips use a saw-like structure to pierce and scrape the flesh until sap begins to flow. They then suck up the juices and leave a surface of patchy white or silvery scrapes. The leaf surface looks scarred or scabby. Eventually, the leaves look like all the chlorophyll has been drained, and they turn white. Thrips leave behind greenish black specks of poop on and under leaves. Thrip damage can resemble that of spider mites or leaf miners at first, but more severe cases result in the color-stripped leaves.

Damaged leaves can’t be healed and their ability to absorb light is compromised. If thrips are not controlled, the plants die. Thrips also carry pathogens including botrytis and yellow dwarf virus that they transfer from plant to plant.

Thrips pierce the leaves, then suck out its contents. Thrips lay eggs on the plants. The larvae hatch and feed for several days before dropping down to the soil to pupate.

Outdoors, thrips hibernate over the winter in soil and plant debris. They become active when the temperature climbs above 60°F (16°C). The warm, stable temperatures of indoor gardens allow them to be active year-round. Thrips are a more serious problem indoors because of this, and also because a natural soil-dwelling fungus that infects thrips pupae is not present indoors.

Reproduction rate and life cycle: Females lay eggs (anywhere from 40 to 300 depending on species) in plant crevices or actually insert them into the leaves and stems. The larvae feed until they enter the pupal stage, when they fall to the ground, where the soil fungi provide some biocontrol outdoors. Depending on the species and temperature (optimum is 77 to 82°F [26 to 28°C], the larval thrips hatch, pupate and mature to egg-laying adults in 7 to 30 days.

Out of the 5,000+ thrips species that have been documented, there are only a select few that are problematic, mainly the western flower thrips (Frankliniella occidentalis), which attacks many plants species. Thrips damage is unique: preferring to live on the underside of the leaf where they feed, small white or silvery dotting can be observed on the top side. Thrips themselves have a very specific body, often referred to as “cigar-shaped”; larvae have a long abdomen that tapers to a point, and are often cream-colored. Adults have feathery wings and though they have a similar body, are larger than the larvae.

Clockwise from top left: 1) Thrips congregating; 2) Single thrip; 3) A thrip curtain at Harborside Farms; 4) Thrip damage

Photos 1-3 by W. Cranshaw, CSU, Bugwood.org. Photo 4 by Ed Rosenthal

Western flower thrips populations have become resistant to many pesticides.

Several biological control organisms have been used effectively in other crops for population control, such as various predatory mites, as well as the minute pirate bug (Orius insidiousis) and predatory mites A. swirskii and A. cucumeris.

Thrips are drawn to the colors blue and yellow, so it’s best to avoid having yellow walls or items around your cannabis gardens. Yellow and blue sticky cards can be used as indicator traps to detect an infestation of thrips. Use garlic in outdoor gardens to deter/repel thrips.

BioCeres WP spores adhere to the insect’s body, germinating then penetrating the cuticle and growing inside, causing white muscardine disease. It will kill insects within 72 hours of application. Targets thrips, whiteflies and aphids. OMRI Listed for organic production. Perfect tank mix partner with AzaGuard.

Voles are common in temperate areas, especially those adjacent to large fields or wooded areas. Unlike their relative, the house mouse, they prefer the outdoors and staying low.

The vole is a small rodent that has a brownish to grayish coloration with small ears, eyes and tail. The vole has seven toes on his front paws and five toes his rear.

A great indicator of a vole problem is the presence of the trails they build as they go to and fro. Droppings and nests with a litter of young are frequently found along their routes.

Voles can wreak havoc on young plants by gnawing the stalk near the base. They also can tunnel through root systems, causing plants to die back or lean over.

Voles are known as meadow mice or field mice in North America. There are approximately 155 species of voles. They are small rodents measuring from 3 to 9 inches in average length. They are mostly known for girdling or eating around the base of plants but may also attack root systems.

Voles like to hide in low vegetation or garden refuse so keep a clean garden floor free from weeds and waste. Remove places where they can hide such as piles of garden supplies or wood piles.

A cat in the garden deters voles.

Predator urine is an effective deterrent.

Place live traps perpendicular to the most trafficked routes or near nesting sites.

Mouse traps baited with peanut butter work as well.

Encircling plant stems with light-colored tree guards or wire mesh helps save large plants from damage.

Whiteflies

Whiteflies are a common pest indoors and outdoors.

Whiteflies resemble tiny white moths but are neither moths nor true flies. They are true bugs, relatives of aphids and scales. They are 0.04 inch (1 mm) long and their soft bodies are covered in a powdery wax which gives them protection and their white color. Whiteflies share similar traits with aphids and mealybugs. They all feed on plant sap and produce honeydew (the substrate necessary for sooty mold). Whiteflies differ from scale bugs regarding mobility. The females of scale bugs are stationary. However, only non-adult stages of whiteflies stay virtually anchored to a single place. The adults fly. Wax production is minimized in comparison to aphids and scale insects only existing either on their bodies or around eggs, which are sometimes arranged in a circular pattern. Whitefly larvea are small insects that look like green or yellow scales adhered to a leaf or stem, and are white-winged as adults, usually preferring the undersides of leaves. Large populations can severely stunt growth and grow to hundreds if given enough time.

Whiteflies infest the undersides of leaves. If the plant is disturbed, they take wing and a mass of tiny white flies can be seen fluttering around the plant.

They suck sap from the plants and are vectors for broad mites and powdery mildew. The plants release sticky honeydew, which can contribute to mold problems on the plants. Leaves appear spotty, droop and lose vigor.

Whiteflies are sap-feeders, like their relatives, aphids and scales.

Correct pest identification is critical for a successful IPM program. ARBICO’s Yellow Pest Insect Traps can be used to attract, trap and monitor pest insects as well as to monitor infestations and to know your pest thresholds and are waterproof for potted plants, greenhouses, or outdoors.

Whiteflies in various life stages

Whiteflies are a pest in big numbers but are not difficult to get rid of. If you think the plants might have whiteflies but are unsure, shake them. You’ll see them flying off, then settling right back onto the leaves.

Reproduction rate and life cycle: Females each lay about 100 tiny eggs on the undersides of leaves. Eggs hatch in about seven to ten days, and the larvae drain sap from leaves. Larvae mature in two to four weeks and the adults live for four to six weeks after that. The reproductive rate is temperature dependent: most whitefly species do best in a temperature range of 80 to 90°F (27 to 33°C).

Keep the temperature of the garden below 80°F (27°C) to slow whitefly reproduction. Clear out plant debris quickly. Install a fine dust filter, at least 400 micron, in the air intake for the grow space to prevent whiteflies from entering through the vents.