Although we briefly introduced traceroute in Chapter 1, Introducing Networks and Protocols, it is worth revisiting in more detail.

While Ping can tell us whether a network path exists between two systems, traceroute can reveal what this path actually is.

Traceroute is used with one argument: the hostname or address you want to map a route to.

On Windows, traceroute is called tracert. Tracert works in a very similar way to the traceroute utility found on Linux and macOS.

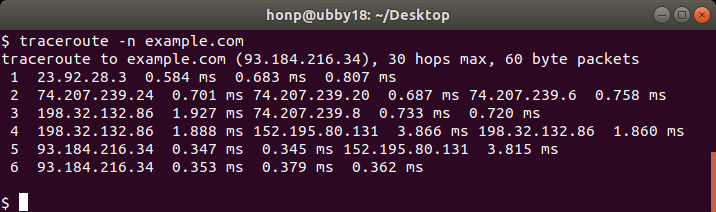

The following screenshot shows the traceroute utility printing the routers used to deliver data to example.com. The -n flag tells traceroute not to perform reverse-DNS lookups for each hop. These lookups are rarely useful and omitting them saves a bit of time and screen space:

The preceding screenshot shows that there are four or five routers (or hops) between us and the destination system at example.com. Traceroute also shows the round-trip time to each intermediate router.

Traceroute sends three messages to each router. This often exposes multiple network paths, and there is no guarantee that any two messages will take precisely the same path.

In the preceding example, we see that the message must first pass through 23.92.28.3. From there, it goes to one of three different systems, which are listed. The message continues until it reaches the destination at hop five or six, depending on the exact path it takes through the network.

This illustrates an interesting point: you shouldn't assume that two consecutive packets take the same network path.