A bloodthirsty enemy struck in London on June 3, 1982. His Jewish victim was the Israeli ambassador to the U.K., Shlomo Argov, shot through the head by a lone assailant as he left a dinner at the Dorchester hotel. The injury left him mentally and physically incapacitated for the rest of his life.

The attack was perpetrated by the Abu Nidal group, headquartered in Baghdad. Abu Nidal, or Sabri al-Bana, broke away from the PLO years before and was a virulent foe of Yasser Arafat, the PLO chairman, whom he called “the Jewess’s son” and had tried in the past to assassinate.1 But none of that was of any interest to the cabinet, which convened in emergency session the next day. “Abu Nidal, Abu Shmidal,” Chief of Staff Eitan retorted to the intelligence briefings. “They’re all PLO. We need to f—k the PLO.”2 He was out of line, but he perfectly expressed the sense of the meeting.

Prime Minister Begin preferred not to grace Palestinian terrorists with any name or initials. They were all hamenuvalim, the swine. No country on earth would fail to respond to an attack like that, he said. Israel had desisted for long enough from hitting the PLO in Lebanon. To continue to desist would be absurd.3 But Begin did not propose the invasion of south Lebanon at this stage. His decision was to bomb PLO bases and depots in south Lebanon and in the Beirut suburbs. The PLO’s response would determine whether Israel would make do with that or launch its long-planned ground assault.

The Israeli warplanes hit nine targets, including a sprawling sports center in south Beirut that served the Palestinian fighters as a training camp. The PLO “signed its own death warrant,” in the words of Ambassador Lewis, by responding with a massive artillery barrage all across the Israeli border zone. Interestingly, neither Arafat nor Sharon was involved in this preliminary round of hostilities. The PLO leader was in Jeddah, on a mediating mission to end the Iran-Iraq War.4 Sharon was on a discreet official visit to Romania.

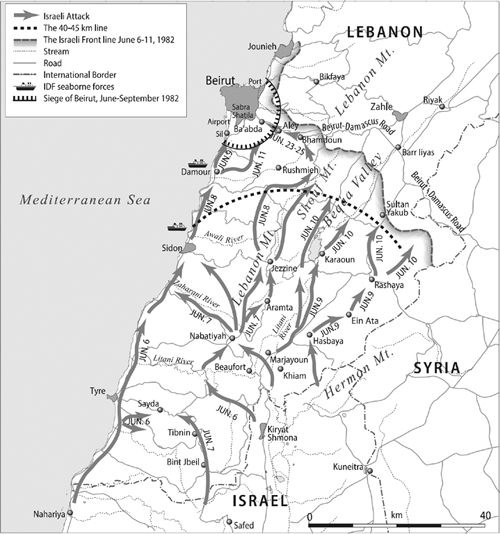

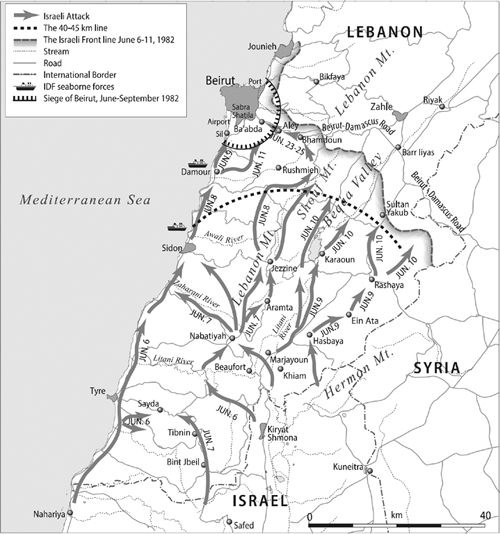

When the cabinet met again, on Saturday night, June 5, in Begin’s official residence, Sharon was back, and the shelling in the north had continued unabated for twenty-four hours. Begin made it clear that he would ask the ministers to approve the ground assault. “It is our fate in Eretz Yisrael to fight and sacrifice. The alternative is Auschwitz.” He asked the minister of defense to take them through the details of the proposed operation once again, “as though for the first time.” Sharon and Eitan described a short, multipronged incursion designed to clear the entire border region of the PLO. The army would advance some forty to forty-five kilometers, they said, the farthest range of the PLO’s artillery. “What about Beirut?” the always-skeptical Ehrlich asked. “Beirut’s out of the picture,” Sharon replied.

Begin acknowledged Ehrlich’s question by saying, “In war, you know how it begins, but you never know how it ends. But let me state very clearly: nothing will be done without a cabinet decision.” Ehrlich was unconvinced and abstained, as did his fellow Likud-Liberal the energy minister, Yitzhak Berman. “You know Sharon,” Ehrlich whispered, as they walked out together. “He’ll dupe everyone. He’ll take us much farther than 40–45 km.”5 The communiqué, meticulously edited by Begin himself, informed the waiting world that

1. the cabinet has decided to instruct the IDF to place all the civilian population of the Galilee beyond the range of the terrorists’ fire from Lebanon, where they, their bases, and their headquarters are concentrated;

2. the name of the operation is Peace for Galilee;

3. during the operation, the Syrian army will not be attacked unless it attacks our forces; and

4. Israel continues to aspire to the signing of a peace treaty with independent Lebanon, its territorial integrity preserved.

This language, and the fraught exchanges leaked from inside the cabinet room, were immediately subjected to the most intense parsing and speculation by Israeli and foreign commentators. Did the reference to the PLO’s “headquarters”—everyone knew they were in Beirut—mean that the IDF was headed for Beirut after all? And what would happen if the Syrians did attack “our forces”? Would there be war between Israel and Syria? What was the reference to a “peace treaty with independent Lebanon”? Did that mean Israel would stay and intervene in Lebanese politics in order to install its ally the Maronite Christian leader Bashir Gemayel as the country’s new president? There was no explicit mention of the forty- to forty-five-kilometer line that ostensibly was the limit of the IDF’s intended advance.

In many ways, this ongoing exegesis was a microcosm of the months to come and indeed of the years of political and historical argument that followed. The same questions resounded: What did Sharon say? And what did he conceal? How much did Begin know? Were the ministers misled?

For Sharon, Begin’s state of mind was crucial. If the defense minister left the prime minister out of the loop, then he was guilty, in effect, of a sort of putsch. If, on the other hand, Sharon acted in close concert with Begin, then the awareness or understanding of the other ministers at any given point was less important in terms of constitutional propriety. In wartime, after all, a small cabal of ministers led by the prime minister always runs things, to the exclusion of others.

Moshe Nissim, who was minister of justice under Begin, insisted years later that the ministers were fully informed at all times. “I’ve got a very great deal against Sharon,” said Nissim, who was to become a bitter political foe of Sharon’s in the decade following the war. “But those who say he duped us and misled us are simply distorting. They’re trying to justify themselves, to escape criticism, to pretend they didn’t know or didn’t see when things began to go wrong. I was actually among the few who opposed the war that first Saturday night. I spoke against it. I said the casualties would be too high. But I said, ‘I can see there is a large majority in favor, so I will vote in favor, too, though with a heavy heart.’ ”

The critics claimed that Sharon presented the cabinet, time after time, with faits accomplis on the ground and then argued that unless additional forward movements were approved, the troops would be in danger. Nissim did not deny this dynamic. But he insisted that the ministers, himself included, were open-eyed participants in it, not blind dupes. They visited the battlefields or studied the maps. “Let’s be honest … I’m not going to change my tune to the media’s rhythm, to the media attacks on Sharon.”6

Begin’s attitude during the buildup to the war was, as we have seen, implacably belligerent toward the PLO and expansively supportive of the Christians. There is overwhelming evidence that this remained the case throughout. Once again, as so often in his career, Sharon was the executor of the policy; despite his new eminence, he was not its conceiver or its instigator. Begin’s apologists, however, among them his son, Benny, subsequently charged Sharon with misleading Begin, and Sharon fought them for years after to clear himself of that charge.

From the start, Israeli ground forces were never able to bring their considerably superior firepower fully to bear.a Four IDF armored columns streamed across the border into Lebanon. In the west, the Israeli tanks and artillery pushed up the heavily populated coastal strip toward Beirut, battling entrenched and determined PLO defenders all the way. At first, the advancing columns swung around the coastal towns of Tyre and Sidon and the large Palestinian refugee camp at Ein Hilwe near Sidon. Palestinian forces there were to be mopped up subsequently. But the “mopping up” proved tougher and much bloodier than had been envisaged. Civilian casualties mounted; fleeing refugees clogged the roads.

The world media, fed by the Palestinians—the IDF ill-advisedly barred reporters from covering the battles from the Israeli side—relayed horrific accounts of mass death and dislocation in perennially war-torn Lebanon. The figures widely quoted—Anthony Lewis, the noted columnist, cited them in The New York Times—10,000 killed and 600,000 made homeless, were later debunked. There weren’t 600,000 people living in the entire area that the IDF had taken at this time. But the damage to Israel was deep and lasting. As the war dragged on into the summer, few in the world’s chanceries were disposed to listen to Sharon’s or Begin’s justifications.

In the east, two divisions fought together as a corps under the command of Avigdor “Yanosh” Ben-Gal. An initial advance on the first day drew Syrian fire. PLO artillery embedded within the Syrian lines was also firing sporadically across the border onto Israeli villages.7 Sharon ordered the army to prepare an advance along the west of the Beqáa Valley, in a movement demonstratively designed to outflank the Syrian deployment in the valley. This, he told the cabinet that night, would hopefully persuade the Syrians to withdraw northward—and take the PLO with them. Begin extolled this tactic as a “Hannibal maneuver.”

During the night, meanwhile, the crack reconnaissance company of the Golani Brigade succeeded in storming the most symbolic stronghold in south Lebanon: the ruined Crusader castle of Beaufort. Towering over the surrounding country, this fortress for years had given PLO gunners an unrivaled view toward their targets across the border while affording them, with its massive stone walls and underground chambers, effective protection from even the most furious Israeli bombing.

Sharon and Eitan’s critics argued that the advancing armored units could have skirted the Beaufort and left it to fall later without a fight. In the event, the PLO defenders put up a spirited fight, and six Golani men died, including the company commander. To make matters much worse, Begin and Sharon, who arrived by helicopter on Monday afternoon and clambered about the fortress while the television cameras whirred, were not properly briefed on the battle and, in Sharon’s words, “expressed our happiness that there had been no losses. In so doing we inadvertently caused great pain to the families of the soldiers killed in this battle.”

This macabre episode fed a by-now-nagging feeling of discomfort among the few skeptical ministers about the way the “twenty-four- to forty-eight-hour, forty- to forty-five-kilometer operation” against the PLO in south Lebanon was being conducted. It already seemed to be evolving into running battles between sizable armored formations of the Israeli and Syrian armies. Sharon’s “Hannibal maneuver” did not succeed. Not only did the Syrian units in the Beqáa fail to withdraw, but other units were quickly brought in from the north to confront the Israeli armor advancing gingerly along the narrow, winding mountain roads. During Monday, large-scale battles developed at several points across the central and eastern sectors.

The sense of unease deepened and spread in the wake of Begin’s speech in the Knesset the next day, Tuesday, June 8. By the time he spoke, Israeli units converging on the strategic mountain town of Jezzine were engaged in pitched battles with the Syrian defenders. Yet Begin proclaimed, “We do not want war with Syria,” employing all his rhetorical theatricality. “From this rostrum, I call on President Assad to instruct the Syrian army not to harm Israeli soldiers, and then nothing will happen to them. We do not want to harm anyone. We want only one thing: That no-one harm our settlements in the Galilee any more … If we achieve the 40 kilometer line from our northern border, the job is done, all fighting will cease. I make this appeal to the Syrian President.”

The Syrian president and his soldiers in the field must have been bemused if they were listening. The Israeli prime minister was plainly out of touch with events on the ground. As the day wore on and the true situation emerged from the battlefield fog, awkward questions began to surface among Israeli politicians and pundits. Did the prime minister know what was going on in real time? Were Sharon and the army keeping things from him? Did he understand the risk of a full-fledged war with the Syrians, a war that might spread from south Lebanon to the Golan Heights?

Sharon, to his credit, spoke without Begin’s glib certitude. “I cannot say to the cabinet that there will not be a clash with the Syrians,” he warned on Saturday night. “There is that danger, because of the terrain in Lebanon and the proximity of the various forces and lines. But we will make every effort, and we will tell the Syrians that we harbor no hostile intention against them.”8

The critics, whose numbers grew as the war dragged on, accused Sharon and Begin of deliberately courting the fight with Syria as part of their plan to install Bashir Gemayel as Lebanon’s new president and weaken the Syrians’ hold over his country so that he would sign a peace accord with Israel. Sharon and Begin insisted that these were not their war aims but only ancillary benefits that might accrue from the principal war aim, which was to uproot the PLO from the south.

Begin did have an additional war aim that he did not conceal, though neither did he proclaim it publicly as an “official” part of his policy. The war in Lebanon, he believed, would heal the nation from the trauma of the Yom Kippur War.9 Yom Kippur had been “a darkening of the lights,” Begin told Eitan when he visited the chief of staff’s forward headquarters on Monday, June 7, before they flew on together to the Beaufort. “But that was a long time ago,” the prime minister continued, waxing euphoric. “We are coming out of that trauma. Now [with this war] we are coming out of it.”10 Two days later, he asserted proudly that “in Operation Peace for Galilee the nation of Israel has overcome the trauma of the Yom Kippur War.”11

To be fair, Begin delivered that exultant verdict on Wednesday, June 9, at the moment of Israel’s undeniably momentous success against the Syrians—and at the moment before the war in Lebanon began to go grievously wrong.

On Tuesday, one Israeli column advanced north, to within striking distance of the Beirut–Damascus road. If the road were cut, the Syrian force in Beirut, some seven thousand men, would be effectively cut off. With the Christian Phalange’s Lebanese Forces holding the territory north of Beirut, moreover, the Palestinian fighters holed up in the city and all those fleeing there from the fighting in the south would find themselves trapped. Israel’s paramount interest in reaching and cutting the road was now both strikingly evident and tangibly feasible.

But the Syrians were not done for yet. They had their anti-aircraft missiles, deployed thickly in the Beqáa. On the basis of the Yom Kippur War experience, the Syrian commanders were confident that the SAM-6s and SAM-3s gave their ground forces reliable protection against the Israeli Air Force. In early dogfights over the border region the Syrians had lost six MiGs. The IAF was intact. But now the fighting was moving toward the areas covered by the missile umbrella. Sharon urged the cabinet to approve a concerted aerial attack on the missile batteries. His rationale, as so often in this war, was unarguable: soldiers’ lives were on the line.

At 2:00 p.m. on Wednesday, June 9, the IAF struck. Within an hour, nineteen of the twenty-three Syrian batteries were smoldering wrecks and the other four badly damaged. The IAF was still entirely intact. The Syrian commanders sent up, by their own account, a hundred MiGs to challenge the Israeli warplanes. Twenty-nine of them were downed before the day was over. Israeli losses were still nil.b

For the IAF, it was “a sensational triumph, one which can be compared only with its successes on the morning of 5 June 1967 … or its successful bombing of the Iraqi nuclear reactor on 7 June 1981.”12 The Israeli success against the Soviet-supplied missiles prompted discreet jubilation among intelligence experts and aerial and electronic warfare officers in Washington and serious ripples of concern in Moscow.13 For Syria, the results of the air battle may have influenced its decision not to extend the land engagements to the Golan Heights.14

Despite the aerial victory, the land battles with the Syrians over the next two days were tough, and the IDF sustained painful losses. In the central sector, the Israeli armor ran up against strongly entrenched units of Syrian commandos equipped with antitank missiles and fighting hard to prevent the tanks breaking through to the road. Syrian attack helicopters joined the fray, to deadly effect.

On the night of June 10, an Israeli tank battalion, apparently losing its way, found itself entrapped in a narrow defile near Sultan Yakub, fired on from all sides by Syrian infantry dug into the hills. Due to administrative snafus and lapses in communications, the large IDF forces in the area were not directed to relieve the hard-pressed battalion. Finally, under cover of artillery fire, the surviving tanks and APCs retreated to the IDF lines. Twenty Israeli soldiers died at Sultan Yakub, and another thirty were injured. Six more were left on the battlefield.c

All in all, during the first week of the war the Syrians lost close to three hundred tanks compared with barely over a tenth of that figure on the Israeli side. On paper, then, especially when joined with the destruction of the ground-to-air missiles and the totally lopsided outcome of the aerial dogfights, Israel had scored a convincing victory over Syria. Nevertheless, the stinging defeat at Sultan Yakub, exacerbated by the lingering uncertainty surrounding the MIAs, cast a pall for Israelis even over this relatively brief, relatively successful part of “Operation Peace for Galilee.”

In the west, too, the first week’s fighting against the PLO had proved harder and more costly than had been anticipated. Calls by the IDF to civilians in Tyre and Sidon to flee to the beaches were heeded in part, but the numbers of dead and wounded among noncombatants were still very high, and damage to civilian buildings and infrastructure was extensive. As they labored up the coast toward Beirut, the Israeli columns encountered ever tougher Palestinian resistance. Palestinian boys barely in their teens wielded rocket-propelled grenade launchers to devastating effect. IDF casualties mounted daily. At the village of Sil, just south of the capital, Syrian commando units took part in the battle alongside the PLO fighters. From Sil, part of the Israeli force veered east, toward the suburb of Ba’abda on the southeastern edge of Beirut, where the Lebanese Ministry of Defense and the official presidential residence were situated.

On the morning of Thursday, the tenth, Sharon explained to the cabinet that IDF forces from the west and from the center would try to reach the road at Aley and cut it there. It was hard going, Sharon stressed, not a picnic at all. The roads were steep and narrow and frequently mined. The advancing columns came under attack from close range.d

The troops would be close to Beirut, Sharon continued, but were explicitly instructed not to advance into the city itself. Dealing with Beirut, as he put it, would be better left to the Lebanese government and the Lebanese army. As to the IDF linking up with the Christian Phalange forces, “We won’t initiate it, but if they approach us, we won’t reject them out of hand.”15

Click here to see a larger image.

This last was blatantly disingenuous: a Phalange liaison officer was already stationed with the IDF forward command post at Ba’abda. Bashir Gemayel himself had visited Northern Command headquarters at Safed on June 8, the third day of the war, and conferred there with Eitan.16 But the Phalange forces’ involvement in the war thus far had been peripheral and ineffective. Their leader, carefully nursing his presidential ambitions, made it clear to the Israelis that he must avoid the perception of being in cahoots with their invasion of his country.

By this time, the Soviets’ concern for their Syrian client was producing anxious Soviet pressure on Washington. The situation was growing “extremely dangerous,” Leonid Brezhnev wrote to Ronald Reagan, and was rife with “seeds of escalation.” The United States itself was growing hourly more anxious over the fate of Lebanon and the repercussions of the widening war throughout the Arab world. Vice President George Bush and Defense Secretary Weinberger had urged tough measures from the outset to rein in Israel. But Secretary of State Haig, traveling in Europe with the president, had held, with Reagan, to a more sympathetic line. The U.S. special envoy Habib rushed back to the region at the outbreak of the war. He tried to convey Begin’s message of reassurance to Hafez Assad in Damascus. Now he was urging stern U.S. diplomacy to procure a cease-fire.

“As for Begin,” Haig recalled, “he was not inclined toward a cease-fire until Israeli objectives had been achieved. But what were these objectives? Were they the ones we had heard earlier in the war or were they now the more ambitious goals of the Sharon plan?” In fact they were the latter, and always had been.e Begin was entirely supportive as Sharon explained to the ministers that the army needed a little more time to take the road. He warded off direct demands from Reagan to put a cease-fire in place on Thursday. Finally, with the troops close to Aley, although not there yet, he could resist no longer. He ordered the end of hostilities at midday on Friday.

Had the cease-fire held, Habib might have succeeded at this stage in peaceably negotiating the PLO’s withdrawal from Beirut. The United States supported this Israeli demand. The deal would presumably have entailed Israel’s withdrawal, too. “Habib was trying to work out an arrangement which would have the PLO evacuate Beirut and would have brought the conflict to an end,” Sam Lewis recalled.17

But the cease-fire collapsed and, though reinstated, continued to collapse again and again as all the while IDF units pushed steadily forward until they reached the road and clamped tight their ring of steel around Beirut. Instead of peaceable negotiations, seventy days of siege ensued, amid incessant bombardment and hardship for the people of the city—and deepening opprobrium for Israel in the world—until a deal was finally struck and Yasser Arafat and his men were evacuated under the close protection of American, French, and Italian troops.

The casualties that the IDF sustained—some three hundred soldiers dead and more than fifteen hundred injured by the end of this period—and the enormous damage to the American relationship and to Israel’s international standing clearly outweighed any benefit obtained from driving the PLO from Beirut. All that was true, moreover, before the massacre at Sabra and Shatila in September. But neither Begin nor Sharon had the statesmanship to break out of the vortex of their own swirling, arrogant ambitions. Together they were sucked down into the morass of murderous Lebanese strife.

On June 22, with Begin on a visit to Washington (and Ehrlich standing in as acting prime minister), the IDF launched a concerted attack eastward along the road, supported by artillery and airpower. Sharon was determined to broaden Israel’s grip on the road, making the siege of the city impermeable. The Syrians fought back hard with their antitank commando units, and it was only after sixty hours of battle that the stretch of road from Bhamdoun to Aley was clear of them. The cost to Israel of that battle alone: another 28 soldiers killed and 168 wounded.18

In the cabinet, ministers demanded of Ehrlich that he put a stop to the renewed fighting. Ehrlich admitted that he had had no prior knowledge of it. Again, Sharon and Eitan resorted to their soldiers-in-danger and enemy-violations arguments. But increasingly these were losing their credibility. Ministers were being assailed by complaints from relatives and friends in the reserves who felt the war was dragging on needlessly, at mounting cost in life and limb. Some brought reports depicting Sharon, on the front lines, mocking his cabinet colleagues. “In the morning I fight the terrorists,” he was heard to say, “and in the evening I go back to Jerusalem to fight in cabinet.”

Begin appeared to emerge from the White House more or less unscathed, despite a deepening distrust and animosity toward him and Sharon among many senior U.S. officials. “Reagan Backs Israel” was The Washington Post headline the next morning. “Reagan and Begin Appear in Accord,” The New York Times reported. But the newspapers were reading it wrong, as was Begin himself. “The President’s anger with Begin, fed by the greater anger of Weinberger (who was reportedly exploring ways to cut off military deliveries to Israel) and others, seemed to grow by the day,” Alexander Haig wrote. And with Haig himself about to leave office, Israel’s war aims would lose their only advocate in the Reagan administration.

Haig believed with Begin and Sharon that sustained, relentless Israeli pressure in Lebanon would bring about the PLO’s departure. The secretary designate, George Shultz, was not convinced.

Begin, however, relished the moment. Addressing the Knesset on June 29, he insisted that the IDF was “near Beirut … at the gates of Beirut” but absolutely not in Beirut. “I’ve said all along that we don’t want to enter Beirut, neither west Beirut nor east Beirut. We totally didn’t want to. And we still don’t want to today. But, for God’s sake, you are all experienced people; I appeal to you as a friend to friends, as a Jew to other Jews.… [A]s a result of developments … we are deployed today alongside Beirut, and the terrorists are trapped within.… Mr. Speaker, happy and fortunate is the nation that has such an army; happy and fortunate is the army that has such a general as Raful as its commander; and happy and fortunate is the state that has Ariel Sharon as its defense minister. With all my heart I say this.”19

Habib was working on a package that was to include a U.S. Marine presence in Beirut to ensure—and also protect—the PLO’s departure. Sharon inveighed against this on the grounds that even after the evacuation some PLO men would be left behind and would need to be flushed out. But the marine presence would prevent or impair that necessary activity.20

The PLO for its part, gradually acquiescing in the eventual likelihood of its being forced out, demanded Israel’s withdrawal, too, and the deployment of a multinational force in Beirut to defend the Palestinian communities living in the sprawling refugee camps in the south of the city after the fighters had left.f

A cabinet communiqué at the end of July proclaimed that “Israel is willing to accept a cease-fire in Lebanon, with the explicit condition that it be absolute and mutual.” With breathtaking chutzpah, it went on to announce that “the Government of Israel is of the view that measures should begin, through the Lebanese government, to provide accommodation for refugees in Lebanon, in preparation for the winter months,” and that “the cabinet decided to establish a ministerial committee … to elaborate principles, ways and means for a solution of the refugee problem in the Middle East through their resettlement. The committee will be aided by experts and will submit its recommendations to the cabinet.”

By the first week of August, Israel was facing the full fury of an American president who felt his friendship had been betrayed. On August 2, in the Oval Office, a somber foreign minister Shamir listened while Reagan railed over television footage from Beirut “of babies with their arms blown off.” The previous day, Israel had bombed the southern suburbs of Beirut for ten straight hours. “ ‘If you invade West Beirut, it would have the most grave, most grievous, consequences for our relationship,’ the president told Shamir and added, ‘Should these Israeli practices continue, it will become increasingly difficult to defend the proposition that Israeli use of U.S. arms is for defensive purposes.’ ”21

The crisis escalated further that same night when Habib called the State Department, as Shultz recalled,

screaming in rage…[that] the IDF shelling was the worst he had seen in eight weeks of war … Begin was calmly denying that any shelling was taking place; this had just been confirmed by Defense Minister Ariel Sharon … The United States was being fed hysterical, inflated reporting, Begin said.

[Charles] Hill [a foreign service officer] relayed this to Habib. “Oh, yeah?” Habib said, and held his tacsat earpiece out the window so that we could hear the Israeli artillery firing. Hill counted eight shells within thirty seconds from IDF artillery batteries located just below Habib’s position … Meanwhile, back in Israel, Ariel Sharon was on the phone to Bill Brown [the deputy chief of mission], heaping scorn on our reports: they are false, hysterical, unprofessional; the IDF has done nothing like what is being claimed, Sharon said.22

Sam Lewis picks up the story. “Shultz’s U.S. Marine Corps background kicked in at that point; his face turned almost purple as he told Shamir just what Habib was personally watching; he also told him to set the Prime Minister straight and see to it that the bombardment ceased forthwith.” Reagan wrote to Begin warning that the relationship between their two nations hung in the balance.

Begin’s gushing reply, comparing Arafat holed up in West Beirut to Hitler in his bunker in 1945, left Reagan cold. Begin for his part was heard to mutter in regard to the American president, “Jews bend the knee only before God.”23

IDF troops were dispatched to Jounieh on August 8 deliberately to harass and disrupt the landing of the first units of the multinational force (MNF), which was to comprise American, French, and Italian troops. American helicopters tried to ferry the French troops ashore, but Israeli jeeps raced around the designated landing pad to prevent them from doing so. Presumably, this was Sharon’s way of underscoring his continued objection to the MNF deploying in Beirut before the PLO had left.

Habib had managed to find safe havens for the PLO men in Tunisia and several other Arab countries. On August 10, Israel received a draft of Habib’s proposed “package deal” for finally ending the war. In a compromise between Israeli demands and Palestinian fears, it provided for the evacuation by sea of part of the PLO a few days before the deployment of the MNF. After that, the remainder of the PLO and the Syrian troops in Beirut would be evacuated from Lebanon under MNF supervision. The PLO was to be allowed to carry its small arms, but heavy weapons would be handed over to the Lebanese army. The MNF would remain in Beirut for one month.

Sharon was unhappy with the timetable and wanted assurances that if the evacuation stopped, the MNF would be withdrawn. The cabinet decided to accept the package “in principle.” But in defiance of the cabinet’s decision in principle, the air force was ordered to prepare another massive bombardment of Beirut. In addition, large forces of long- and medium-range artillery were deployed around Beirut. They were instructed to prepare to lay down a “rolling screen of fire” on the Palestinian southern suburbs, a bombardment more concentrated and devastating than even the air force could deliver. On August 12, this vast firepower began to rain down on the city. The IAF flew more than a hundred bombing sorties. Civilian casualties mounted by the hour.

Reagan called Begin and spoke, deliberately, of a “holocaust.” Begin instinctively bridled. Reagan did not back off and gave Begin an “ultimatum” to stop the bombardment forthwith. Begin reported back to the president that the bombing had stopped at 5:00 p.m. The cabinet had also decided, he said, that any further use of the air force would require the prime minister’s personal approval. Sharon was no longer empowered to bomb Beirut.

Begin’s public clipping of Sharon’s wings reflected a bitter debate inside the cabinet room, the angriest and bitterest since the war began. Minister after minister accused Sharon of deliberately seeking to upend the American-mediated package deal.

There had been earlier signs of a weakening in Sharon’s all-powerful position. On July 30, the housing minister, David Levy, pointedly asked Begin at cabinet if he knew about certain troop movements around the Beirut airport, and Begin replied: “David, I always know about everything. Some things I know about before, and some things after.” Sharp-eared ministers discerned a note of exasperation in his voice.24

A week later, Minister of the Interior Burg asked Begin about the call‑up of a reserves paratroop brigade (his son’s) at short notice. He feared it meant the army was preparing to storm West Beirut, with the inevitably high loss of life that that would entail. He warned the prime minister that his party, the National Religious Party, would leave the coalition if that happened. Begin said he knew nothing about the call‑up and hadn’t approved it. He called Sharon, who readily confirmed that he had approved it. After all, he explained, the two of them had discussed the prospect of storming the city, albeit as a last resort if the diplomacy failed, and calling up reserves for this eventuality was “obvious.” “Obvious? What do you mean obvious? How can you do that without [my] approval? So many people know and the prime minister doesn’t know!” Sharon apologized profusely.25

Outrage over the bombings put paid to any lingering solidarity in the Labor opposition with the government at war. Yitzhak Rabin, Labor’s premier defense spokesman, had supported the siege of Beirut, including the cutoff of water, much to the chagrin of his own party doves. Now the doves called for Sharon’s dismissal and for a commission of inquiry to be set up to investigate the war.26 Sharon for his part began accusing the opposition of cynically exploiting the war for political ends. Labor was “marshaling all its great media strength and international resources … to unseat the government—and all this while Israeli forces were in the field in mid-battle. It was unprecedented and, to anyone with a sense of Israeli political history, unbelievable.”27

On August 21, the evacuation of Beirut began. It lasted for twelve days, and by the end 14,298 armed men had been ferried out of the city. More than 8,000 of them were PLO men and the remainder Syrian soldiers. Another 664 women and children were evacuated with them. Some 8,150 of the evacuees were taken out by sea, to Tunisia and seven other Arab countries (Syria, North Yemen, South Yemen, Algeria, Sudan, Iraq, and Jordan). The rest went overland, along the Beirut–Damascus road, with Israeli soldiers shouting obscenities at them from the hillsides.

Whether the Israeli military pressure or the dogged American diplomacy was the primary reason for Arafat’s agreement to go, Sharon felt vindicated. “This mass expulsion was an event whose importance could hardly be exaggerated. Here was the first step in what I saw as a process that would lead to a peace treaty between ourselves and the new Lebanese government. Hardly less significant, the PLO’s defeat [opened] the possibility of a rational dialogue between ourselves and Palestinians not dedicated to our destruction.”28

Even the evacuation occasioned a furious altercation between Israel and America, an altercation that, incredibly, almost turned violent. The casus belli was a number of jeeps that the departing Palestinians had loaded onto a ferry that was part of the evacuation fleet. Sharon ordered the evacuation stopped until the jeeps were off-loaded: the agreement permitted personal weapons, not jeeps.

“Sam Lewis approached Begin about it,” Shultz writes, “and the prime minister exploded: ‘They are not an army! They are rabble! Let Bourguiba [the president of Tunisia] take them in and buy them Cadillacs.’ We told the Israelis that the ship was going to leave … The Joint Chiefs of Staff instructed our naval assets in the area to prepare to defend the car ferry, and themselves, against Israeli attack … Lewis told Begin we would give the order to sail, and we hoped that Israel would not try to block the ship’s departure … The ship sailed.”g

On Monday, August 30, Arafat embarked on a Greek freighter, escorted by the Greek warship Croesus. The Sixth Fleet provided air cover. Israeli marksmen stationed on nearby rooftops had the PLO chairman in the sights. But Begin was personally committed to Reagan to let him sail unharmed.

Meanwhile, on August 23, Bashir Gemayel was elected president of Lebanon by the parliament. He made a point of declaring, both before and after his election, that he had not colluded with the Israeli invaders and that he did not propose to sign a peace treaty with Israel.29 This left the Israelis still divided along the lines that had evolved over the previous two years. Many of the army commanders had little faith in Gemayel and his Phalange. They felt their view was amply borne out by the Christians’ stolid reluctance to take any serious role in the fighting over the past three months or even to say anything publicly that would sound like support for the Israeli goals (which were, after all, their own goals, too). Key members of the Mossad, however, as well as Begin and Sharon and Chief of Staff Eitan, continued to believe that once Gemayel was firmly installed, he would conclude a formal peace accord with Israel that would have important political and economic repercussions throughout the Arab world. They suspected that the Americans, and specifically Habib and his deputy, Morris Draper, were advising Gemayel to avoid openly friendly relations with Israel.30

Begin’s—and Gemayel’s—painful awakening came on the night of August 31, in the northern border town of Nahariya, where Begin and his wife were briefly vacationing in a pointed demonstration of how quiet and peaceful the border area was now. Gemayel arrived for a meeting with the prime minister at a nearby military base. It ought to have been an occasion for mutual congratulation and heartfelt, if discreet, celebration. Instead, the president-elect encountered a cold and sullen Begin, who barely returned his embrace and immediately launched into a grudging congratulatory speech replete with heavy hints about the need now to pay outstanding bills.

They then retired to a separate room, with only a handful of advisers on each side. But Begin’s tone and tenor did not change. “Where do we stand regarding the peace treaty?” he began truculently. Gemayel tried to answer discursively, explaining that he absolutely did want “real peace, in the long term” but that he wasn’t the sole decision maker. There was a government and a parliament. It would not do to rush things, either politically or militarily.

Gemayel spoke about an “order of priorities” that he had discussed with the Americans. The main thing now was to get the Syrians and the Palestinians out of the Beqáa and out of the north of the country. Begin interrupted. He wanted a firm deadline for signing a peace treaty. He suggested December 31. Gemayel balked. He would need at least a year, he said.

“From the moment Gemayel was elected,” Yitzhak Shamir recalled years later, “he no longer wanted to be an ally. He evaded and equivocated, and ever since then Begin was not the same man. It was a grievous blow for him to see that after all our help, the man was disloyal.”31

Both Sharon and Eitan (separately) visited Gemayel during the following fortnight in an effort to patch things up. Sharon dined at the Gemayel family estate at Bikfaya on the evening of August 12. “The atmosphere was especially warm,” he wrote. “I knew the first item of business was to allay the hard feelings that had developed between Bashir and Begin at … Nahariya. The chemistry that night had not been good.” It was different now. “Bashir and his wife, Solange, were happy and obviously excited about the inauguration, and a feeling of intimacy pervaded the room as Bashir and I sat down to talk over the steps he planned to take as president.”

The ironic truth is that it wasn’t Gemayel’s extreme caution—not to say his pusillanimity, or even infidelity—that blackened Begin’s mood on that fateful night in Nahariya. That had occurred earlier in the day, in a terse meeting with Ambassador Lewis, who arrived in Nahariya to deliver in letter form and verbally an entirely unexpected American plan for Israeli-Palestinian peace. The bottom line was that Israel must eventually cede much of the West Bank and Gaza and in the meantime must stop its settlement building. “It was as if he had been hit in the solar plexus with a sledge hammer,” the Foreign Ministry director, David Kimche, recalled, describing Begin’s reaction.32 Begin himself muttered through clenched teeth, “The battle for Eretz Yisrael has begun.”

Almost as if to mock Begin, or to take revenge on him, the American plan stressed repeatedly that it sought to build on “the opportunity” offered by the Lebanon War. The war had demonstrated two key things, Reagan wrote:

First, the military losses of the PLO have not diminished the yearning of the Palestinian people for a just solution of their claims; and, second, while Israel’s military successes in Lebanon have demonstrated that its armed forces are second to none in the region, they alone cannot bring just and lasting peace to Israel and her neighbors…

Palestinians feel strongly that their cause is more than a question of refugees. I agree. The Camp David agreement recognized that fact when it spoke of “the legitimate rights of the Palestinian people and their just requirements …”

The United States will not support the use of any additional land for the purpose of settlements during the transitional period. Indeed, the immediate adoption of a settlement freeze by Israel, more than any other action, could create the confidence needed.

This, ironic perhaps in terms of American politics, signaled Reagan’s endorsement of the plain, straightforward reading of the language of Camp David, the reading of his unloved predecessor, Jimmy Carter. And now—most ironic of all in hindsight—Reagan offered his solution: no Palestinian state; no Israeli annexation; but Palestinian self-rule under Jordan. The irony lies in the sad fact that a Likud-led government in Israel today, let alone a more dovish government, would grab at these terms with both hands—if only they were still available.

Begin rejected them with both hands. He cut short his holiday and convened the cabinet for a somber session ending with a bitterly truculent communiqué. “The positions conveyed to the Prime Minister of Israel on behalf of the President of the United States consist of partial quotations from the Camp David agreements, or are nowhere mentioned in that agreement or contradict it entirely … Were the American plan to be implemented, there would be nothing to prevent King Hussein from inviting his new-found friend, Yasser Arafat, to come to Nablus and hand the rule over to him.”

Instead of concocting this casuistry, designed to perpetuate the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, a more farsighted leader would have been devising urgent plans to end the IDF’s occupation of Lebanon, and most especially of Beirut. As Chaim Herzog writes, the terrible and tragic events that were now to take place in Beirut

totally overshadowed [Israel’s] achievements in the war, which had ended with the PLO and the Syrians ousted from Beirut. If the government of Israel had had the good sense to leave Beirut after the evacuation of the terrorists was completed Israel would have avoided sinking into the mire of Lebanese politics, it would not have entered west Beirut and it would thus not have become involved in any way with the massacre of Palestinians by the Phalange. The IDF’s remaining in Beirut after the [PLO’s] evacuation proves the validity of the ancient rabbinic adage: “Grab too much—and you grab nothing at all.”33

A wholly different view of the war thus far, predominant by now in opposition circles but also troubling some of the ministers, was that the drawn-out hostilities had been, on balance, a disaster for Israel—in terms both of casualties and of the international (including American) opprobrium. Ousting the PLO in no way counterbalanced those setbacks. As for the Syrians, while they had been forced out of the Lebanese capital, they were still firmly entrenched in the northern Beqáa. The hope, moreover, of a peace treaty between Israel and Lebanon had been roughly crushed at the Begin-Gemayel meeting in Nahariya.

From that—negative—assessment of the war, too, the sensible thing for Begin and Sharon to do once the PLO had left was to cut Israel’s losses and get the IDF out, too. But Begin and Sharon were not ready to leave. “Even after the [Begin] meeting with Gemayel,” writes Begin’s biographer,

Sharon had no intention of giving up his aim—clearing out West Beirut, in other words destroying the arms stores hidden there and removing the Palestinian militants who had remained there, particularly in the refugee camps. Because of the heavy price in blood that Israel had already paid in this war, Sharon wanted the Phalange to finish this job, and he sent senior IDF officers and Mossad operatives to coordinate with them. Begin backed him … Sharon did not deviate from the guidelines that Begin laid down. When Begin read intelligence reports, after the PLO’s evacuation, which said that thousands of terrorists had remained in the city, he told the Knesset Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee that Israel still intended to drive out the “hostile elements” that had remained in West Beirut. Once again, Sharon acted to execute the policy goal that Begin determined.34

The intention, then, was for the IDF to stay put while the Lebanese—the Phalange forces, perhaps with the national army, too—cleansed West Beirut of remaining PLO men. But was that the true and full extent of the Israelis’—and Gemayel’s—intention? Or did they envisage, condone, and essentially encourage a much broader ethnic cleansing of Palestinians from Lebanon to be perpetrated, by the Lebanese Christians, by violent means?

The IDF chief of intelligence, Yehoshua Saguy, redoubled his warnings that the Phalange was likely to commit acts of revenge against the Palestinians and its other domestic enemies now that the Syrians and most of the PLO were gone from the capital. For this reason, he urged, the IDF would do well to distance itself from the scene.

On September 14, that option was finally, fatefully rejected. “I was driving toward Tel Aviv,” Sharon writes, “when I received word on the car radio to telephone the defense ministry as soon as possible. Stopping at an army base along the way, I phoned in and was told that an explosion had taken place in an East Beirut building. Our information was that Bashir Gemayel had been inside.” Eight hours later, with the death of the president-elect now confirmed, Begin, Sharon, and Eitan decided that the IDF must take over West Beirut forthwith.

Sharon’s purpose in ordering the IDF into West Beirut—and he confirmed this in his testimony to the Commission of Inquiry into the Events at the Refugee Camps in Beirut (the Kahan Commission)—was to ensure that the remaining PLO men were cleared out in the days ahead by the Lebanese Forces (the Phalange) as had been agreed before the assassination.35 In his conversation with Begin, though, on the night of the assassination, the stress was on the need for the IDF to prevent chaos in the city. Begin said to Eitan, too, on the phone that Muslims must be protected from the Phalange.36

Later that night, Eitan went to the Phalange headquarters at Karantina, where he explained to the stunned and grieving commanders that their leader’s assassination—which everyone attributed to Syrian agents—“had the potential of sparking a new round of violence” and that it could signal a Syrian-PLO effort to reverse the results of the war and get back into Beirut. “I asked them if their forces would be prepared to assist us, and, to my surprise, received an immediate affirmative answer. I asked … that they prepare to capture the Palestinian camps Sabra, Shatila and Fakahani.”37

Was the IDF’s entry, then, designed to ensure the “cleansing” of the Palestinians or to ensure their protection? An official announcement the following day reflected this ambivalence: “IDF forces entered West Beirut to prevent possible grave occurrences and to ensure quiet.”38

At dawn on the fifteenth, IDF troops took over key buildings, road arteries, and intersections in West Beirut, encountering scattered opposition. Sharon flew up later in the morning and met with Eitan and the other senior IDF commanders at a forward command post on a rooftop overlooking Sabra and Shatila. He discussed the plans to send in the Phalange “under the IDF’s supervision.” Then he, too, went to Karantina to talk to the Phalange officers and on to Bikfaya to offer his condolences to the bereaved father, Pierre Gemayel, and to his younger son, Amin.

The next day, Thursday, September 16, CO of Northern Command Amir Drori personally briefed the Phalange officers due to lead the assault on the Palestinian camps. “They were instructed to be careful in their identification of the PLO terrorists,” Sharon recalled. “The mission was only against them. Civilian residents, they were specifically instructed, were not to be harmed.” Brigadier Amos Yaron, the divisional commander, made the same point to Elie Hobeika, the Phalange intelligence chief, who came up to his rooftop command post for final coordination.39

In Jerusalem, meanwhile, Morris Draper, Habib’s deputy, and Sam Lewis were remonstrating vigorously but vainly with Sharon and Eitan over Israel’s cavalier violation of its solemn commitment not to enter West Beirut. Israel had undermined its own credibility, Draper said. Sharon replied there were between two and three thousand Palestinian terrorists left in the Beirut camps—“we’ve even got their names”—and the IDF had taken the western city in order to get them out. The day before, Draper had been treated to the other tack in Israel’s ambivalent—in fact, contradictory—explanation of its decision to enter West Beirut. Israeli forces had been ordered to make some minor positional adjustments—“limited and precautionary,” Begin told him, according to Secretary Shultz’s account. “This was in the interest of security in the city … Specifically, the Israelis said they wanted to prevent the Phalange militia from raiding the Palestinian refugee camps south of the city to avenge Gemayel’s death.”40

By the time the cabinet convened, at seven o’clock on Thursday evening, the Phalange units had entered Sabra and Shatila. “While I was speaking,” Sharon recalled, “a note came in that the Phalangists were now fighting inside the neighborhoods, and as I described this development, there was no negative reaction from any one of the assembled people.”41

This was a remarkably silly lie, given that almost every child in Israel knew by the time it was written, following the Kahan Commission Report, that Minister of Housing David Levy had voiced his grave concern. “When I hear that the Phalangists are already entering a certain neighborhood,” Levy said, “I know what the meaning of revenge is for them, what kind of slaughter. Then no one will believe we went in to create order there, and we will bear the blame.”42h

Levy’s warning went unheeded. The ministers—including the skeptical ones, not just the nodding heads—were more concerned about why the army had been sent into West Beirut without the cabinet’s knowledge, let alone approval, than about David Levy’s pontifications about oriental vendetta lore. The cabinet communiqué, drafted by Begin, rehearsed the ambiguous Israeli line: “In the wake of the assassination of the President-elect Bashir Gemayel, the IDF has seized positions in West Beirut in order to forestall the danger of violence, bloodshed and chaos, as some 2,000 terrorists, equipped with modern and heavy weapons, have remained in Beirut, in flagrant violation of the evacuation agreement.”

The next day, Friday, was Rosh Hashanah eve, the saddest day of the year for Sharon. With Lily and the boys, his mother, and a few friends, he held his annual graveside memorial ceremony for his dead son, Gur. Then he drove to Jerusalem and, together with Shamir, met again with Draper. “I pressed Draper to use his influence to get [the Lebanese government] to order the Lebanese army into the Palestinian neighborhoods.”43

In the Palestinian neighborhoods, meanwhile, unarmed people were being butchered. No IDF personnel had accompanied the Phalangists into the camps, and there was no direct line of vision from the forward command rooftop into the warren of streets and alleys below. But the Phalange operation had proceeded through the night by the light of illumination shells thrown up by an IDF mortar unit, at the request of the Phalange liaison officer.44

And IDF intelligence was not entirely in the dark. One intelligence officer, according to the Kahan Commission, “received a report that the Phalangists’ liaison officer had heard via radio from one of the Phalangists inside the camps that he was holding 45 people. That person asked what he should do with the people, and the liaison officer replied, ‘Do the will of God,’ or words to that effect.”45 Another officer, Lieutenant Elul, “heard a Phalangist officer from the force that had entered the camps tell Elie Hobeika (in Arabic) that there were 50 women and children, and what should he do. Elie Hobeika’s reply over the radio was: ‘This is the last time you’re going to ask me a question like that, you know exactly what to do’; and then raucous laughter broke out among the Phalangist personnel on the roof.”46

Despite these early indications, it took the whole night and half of the day of unhurried paper pushing between Beirut, Northern Command, and Tel Aviv before the senior IDF officers finally decided that, in General Yaron’s words to the commission, “something smelled fishy.” Drori phoned Eitan at noon to say he would end the Phalange operation. “He informed me that they were mopping up houses without removing the civilians,” Eitan writes in his memoirs, “and were shooting at people randomly. I immediately notified the minister of defensei and left my home for Northern Command. I was extremely upset.”

But not upset enough to ensure the operation was shut down at once. “I reached the Phalange headquarters at 3:30 … When I asked for an update on their progress in the camps I was told that all was well and that they had completed the capture of Sabra and Shatila. They told me they had suffered several wounded and killed and requested that we provide them with tractors, so they would be able to destroy the tunnels and trenches they had discovered.”47

Sharon went back to his ranch to celebrate the festival-eve meal quietly with his family. “At 9 p.m. I received a call from Raful Eitan. He had just returned from Beirut, he told me, and there had been problems. During the operation the Phalangist units had caused civilian deaths. ‘They went too far,’ he said.”

Sharon went to bed early, but at 11:30 an Israeli television journalist (and colonel in the reserves), Ron Ben-Yishai, phoned him with a fuller account of what had been going on. As initial rumors of the carnage filtered out, journalists stationed in Beirut began filtering into the camps. Soon, their reports, television footage, and still photographs started flooding the airwaves. The world’s media were swamped with coverage and with commentary, almost all of it unreservedly condemnatory of Israel. All the criticism—of the initial invasion of Lebanon, of the killing of civilians and destruction of property in the coastal towns, of the months-long siege and bombardment of Beirut, of the blatant manipulation of Lebanese domestic politics, and, beneath all this, of Israel’s occupation of the Palestinian territories and denial of Palestinian rights—fed a great wave of fury and revulsion against Israel, against Begin, and most especially against Sharon.

President Reagan voiced horror, too, and demanded that Israeli forces withdraw from West Beirut immediately. “We also expect Israel thereafter to commence serious negotiations which will, first, lead to the earliest possible disengagement of Israeli forces from Beirut and, second, to an agreed framework for the early withdrawal of all foreign forces from Lebanon.”

Begin’s initial, instinctive reaction was the usual mix of forensic polemics and defiant self-righteousness. “A blood libel was plotted against the Jewish state and its government, as well as against the IDF, on Rosh Hashanah,” the cabinet pronounced after an emergency meeting on the night of September 19. “In a place distant from an IDF position, a Lebanese unit entered a refugee camp where terrorists took shelter, in order to arrest them. That unit attacked the civilian population, resulting in many losses of lives … All the accusations—direct or hinted—claiming that the IDF has any responsibility whatsoever for the tragedy in the Shatila camp are groundless. The Cabinet rejects them with disgust … No one will preach to us values of morality and respect for human life.”

The government won a vote of confidence in the Knesset. But the confidence was a splintering facade. Inside the coalition itself there was a growing realization that the opposition’s demands were inescapable: a judicial inquiry would have to be established, and Sharon would have to go. The alternative, political pundits wrote, was that the government itself would implode. One minister, Yitzhak Berman, didn’t wait. He voted in the Knesset in favor of the opposition motion and announced his resignation the same day.

On Saturday night, September 25, Kings of Israel Square in downtown Tel Aviv was thronged with protesters in what the organizers—Peace Now and other groups—claimed was the largest demonstration ever held in Israel: 400,000 people. There had been earlier, smaller protests against the war in the same square during the summer. Naturally, those were seen as associated with the opposition. This one, despite its provenance, was simply too big for such comfortable categorization.

Sharon tried, nevertheless. “We’ve got nothing to hide,” he fulminated on television the following night. “Nothing! Let everything be investigated! Let everyone be investigated! We didn’t want to harm the civilian population. We don’t fight civilians. We weren’t involved.” Israelis needed to understand that behind the calls for an inquiry were “far-reaching political aims. Certainly there is anti-Semitism involved. And there are certain plans that people are trying to impose on us. They’re not after Sharon’s head or Begin’s head. What they’re after is Jerusalem! They’re after Hebron! They’re after Beit-El, they’re after Elon Moreh! And I say this without any intention whatsoever of covering up or minimizing the ghastly outrages that were perpetrated. But we have to understand: We’re up against the whole world.”48

It was a desperate attempt to depict the crisis in political hues and thereby rally the Right. But when the president of the state, Yitzhak Navon, hinted that he would resign if the government did not set up a commission of inquiry, Begin realized the fight was lost. He tried one last wriggle, sending the justice minister, Nissim, to the president of the Supreme Court, Yitzhak Kahan, with a proposal that Kahan personally investigate the massacre rather than appoint a full-fledged commission of inquiry with statutory powers to subpoena witnesses and order discovery of documents. Kahan dismissed that gambit out of hand.49

Begin was able to convince the commission that he did not know in advance that the Phalange forces were being sent into the camps. This proved the key to his exoneration by the commission, which presented its report on February 8, 1983.

The tasks of the Prime Minister are many and diverse, and he was entitled to rely on the optimistic and calming report of the Defense Minister that the entire operation was proceeding without any hitches and in the most satisfactory manner.

As for David Levy’s warning at cabinet,

According to the Prime Minister’s testimony, “no one conceived that atrocities would be committed … simply, none of us, no minister, none of the other participants supposed such a thing …” The Prime Minister attached no importance to Minister Levy’s remarks because the latter did not ask for a discussion or a vote on this subject. When Minister Levy made his remarks, the Prime Minister was busy formulating the concluding resolution of the meeting, and for this reason as well, he did not pay heed to Minister Levy’s remarks.

The commission rejected Begin’s claim that he was “absolutely unaware” of the danger inherent in sending the Phalangists in. After all, Begin himself had explained that the decision to send the IDF into West Beirut was “in order to protect the Moslems from the vengeance of the Phalangists.”

The Prime Minister’s lack of involvement in the entire matter casts on him a certain degree of responsibility … It is sufficient to determine responsibility and there is no need for any further recommendations.

In effect—an acquittal, albeit Begin said when he first read the report that he felt he ought to resign. But he was quickly talked out of that idea by Minister of Justice Nissim and the cabinet secretary, Dan Meridor. The two of them focused Begin on the real political hot potato that emerged unequivocally from the report: the need to fire Sharon.50

The Minister of Defense bears personal responsibility. In our opinion, it is fitting that the Minister of Defense draw the appropriate personal conclusions arising out of the defects revealed with regard to the manner in which he discharged the duties of his office—and if necessary, that the Prime Minister consider whether he should exercise his authority under Section 21-A(a) of the Basic Law: The Government, according to which “the Prime Minister may, after informing the Cabinet of his intention to do so, remove a minister from office.”

Sharon’s guilt was that he should have known.

Responsibility is to be imputed to the Minister of Defense for having disregarded the danger of acts of vengeance and bloodshed by the Phalangists against the population of the refugee camps, and for having failed to take this danger into account when he decided to have the Phalangists enter the camps. In addition, responsibility is to be imputed to the Minister of Defense for not ordering appropriate measures for preventing or reducing the danger of massacre as a condition for the Phalangists’ entry into the camps.

Sharon claimed, like Begin, that no one had imagined that the Phalangists would perpetrate a massacre. And, as with Begin, the commission dismissed that contention as implausible, even specious. Sharon could not claim, as Begin had, that he did not know the Phalangists were being sent into the camps, because it was he and Eitan who decided to send them.

The commission reached essentially the same conclusions regarding Chief of Staff Eitan. In addition, unlike Sharon, it found him guilty of failing to put a stop to the killings as soon as he became aware of them. The commission made it plain that it would have recommended Eitan’s dismissal had he not been at the end of his term as chief of staff anyway. It recommended that Yehoshua Saguy, the director of Military Intelligence, “not continue as director” and that Amos Yaron, the divisional commander, “not serve as a field commander” for at least three years. The Mossad, which had nurtured the alliance with the Phalange, got off scot-free.

No one on the Israeli side was found guilty of direct responsibility for the massacre, only of indirect responsibility. The sole direct perpetrators of the heinous crime were the Phalangists. The “hints and even accusations” that IDF personnel were present in the camps during the massacre were “completely groundless and constitute a baseless libel.” The charges of collusion were similarly specious the commission held.

Sharon demanded that the government reject the commission’s recommendations. When the cabinet convened on the evening of February 10 to discuss the report, the police had to force a path from Sycamore Ranch for Sharon’s car, which was beset by angry demonstrators, many of them from local kibbutzim. In Jerusalem, though, pro-Sharon loyalists were holding a raucous demonstration outside the prime minister’s office when he arrived for the cabinet meeting. “As I stopped for a moment to greet them, I was engulfed by a thousand hands reaching out to shake mine and a thousand expressions of warmth and encouragement. But these supporters were not alone. At the same moment another demonstration came marching through the streets, this one composed of Peace Now people yelling at the top of their lungs, ‘Sharon rotzeach (Sharon the murderer),’ their shouts mixing with ‘Arik, Arik, Arik’ from my supporters.”

In the tense debate, with the noise of the demonstrations wafting through the windows, Sharon warned his colleagues that if they accepted the commission recommendations, they would be “branding the mark of Cain on the foreheads of the Jewish people and on the State of Israel with your own hands.” If, on the other hand, they had the courage to reject the recommendation, which would mean new elections, the Likud would win its greatest victory ever.

By 16 votes to 1, Sharon’s, they voted to accept the recommendations. That meant either that Sharon now resigned or that Begin fired him. Sharon writes that the ministers had seemed upset and jealous at the “gigantic, spontaneous crowd of Likud supporters … It was such an irony, I thought, that these loyal people who had gathered there to help were in fact sealing my fate.”

Incredibly, in an omission more telling than any of the hyperbole, Sharon makes no mention in his book of the fact that a rightist fanatic (not one of the demonstrators in his support) threw a hand grenade into the Peace Now march, killing one prominent activist, Emil Grunzweig, and wounding seven others.

Grunzweig’s death, as well as the dramatic funeral the next day attended by many thousands, was in some way a fitting, tragic, traumatic end to the tragic national trauma of the Lebanon War. Grunzweig himself had served, dutifully if reluctantly, as a reservist in Lebanon.

That same day of the funeral, Friday, Sharon told Begin he had decided to resign. The attorney general had ruled that he could stay on in another ministry or as a minister without portfolio.51 “ ‘When do you want to do it?’ Begin asked. ‘I’ll do it on Monday,’ I answered. ‘Why,’ he said after a pause, ‘should it take so long?’ ”52

One effect of Sharon’s removal from the Defense Ministry was that Israel softened its stance in the ongoing, desultory negotiations with Lebanon—now under the presidency of Bashir Gemayel’s brother, Amin—over a much-watered-down draft peace treaty between the two countries. Sharon’s demand for IDF surveillance stations on Lebanese soil was dropped. Toward the end of April 1983, the U.S. secretary of state, George Shultz, embarked on a Kissinger-style shuttle to try to clinch a deal. Israel continued to dig in its heels over the future status of the South Lebanese Army (SLA), the Israeli-backed, mostly Christian militia under Major Sa’ad Hadad.j The Israeli negotiators insisted that the integrity of this force be maintained, even if it was formally incorporated into the Lebanese army.

Judicious arm-twisting by Shultz eventually persuaded “the Israelis, grudgingly, and the Lebanese, fearfully,” to sign, on May 17, 1983, an “Agreement on Withdrawal of Troops from Lebanon.” The title was deliberately unbombastic. Not a peace treaty, as Israel had originally wanted, but a more modest agreement that the Lebanese parliament could allow itself to ratify without incurring the wrath of Syria and the scorn of other Arab hard-line states. Israeli forces were to withdraw from Lebanon “within 8 to 12 weeks … consistent with the objective of Lebanon that all external forces withdraw from Lebanon.” This was as explicit a reference as could be made, given Lebanese sensitivities, to the unarticulated core of the agreement: that Israel would withdraw when Syria did, or at least when Syria had credibly committed itself to do so.

The two signatories undertook “to settle their disputes by peaceful means” and to create a “Security Region” in south Lebanon. They affirmed that neither would allow itself to be used as a staging ground for hostile activity against the other. Neither country would intervene in the internal affairs of the other or propagandize against the other.

It was a far cry from the full “normalization” that Israel had initially proposed, with embassies, open borders, and trade ties. But it was an undeniable move away from the official boycott of Israel that Lebanon, along with most Arab countries, had maintained until then. And the agreement held out the hope of a further thaw.

Press and public in Israel had not followed the negotiations with much interest. Expectations from the agreement were low, cynicism sky-high. This assessment was quickly vindicated when Syria, and also the Druze community in Lebanon, rejected and condemned the agreement. President Hafez Assad of Syria made it clear that he did not intend to withdraw his troops. President Amin Gemayel’s request that he do so was invalid, he argued. Only the Arab League could legitimately ask him to go. The Soviet Union’s strong backing of Syria meant that this was unlikely to happen.53

The agreement remained on paper only—and in fact not even that, for though it was ratified by his parliament, President Gemayel never actually signed it into law. The inter-confessional civil war gradually resumed in all its bloody and bewildering complexity, with the various armed militias in constantly changing alignments with each other and with the Syrian forces. The Lebanese army seemed powerless to impose the state’s authority. The multinational force had neither the mandate nor the political will to help it do so. Israeli troops, still deployed deep in Lebanon, sustained ever-mounting casualties, sometimes without knowing which of the local militias was shooting at them or why. Diplomats and Mossad emissaries maintained their largely fruitless contacts with the different factions.

The Druze began to make life difficult for the U.S. troops stationed in and around Beirut as part of the multinational force. Druze forces, based high in the Shouf Mountains, started drizzling fire onto the Lebanese army units and American marines on the coastal plain below. Israeli forces in the Shouf also came under attack from Druze guerrillas. An anomalous situation developed in which Israel wanted to withdraw unilaterally from the Shouf, while the Americans pressured it to stay.

Compounding the problem for Israel was the government’s reluctance to admit that it was delaying the withdrawal—and sustaining further pointless casualties—in deference to American demands. On September 4, the eve of Rosh Hashanah, the Israeli army was withdrawn from the Shouf Mountains and from the whole of the Beirut area, regrouping along the Awali River.

On October 23, 1983, a truck packed with dynamite rammed through the inadequately guarded fence of the marine compound in Beirut and blew up, killing 241 American servicemen. That same day, 58 French soldiers serving in the MNF were killed in another suicide attack. Reagan insisted he would not be driven out by terror. The marines were replaced, and American forces—including the aged battleship New Jersey, anchored off Beirut—started firing back at their various shadowy attackers. But Washington’s heart was no longer in this Lebanese misadventure. Weinberger wanted out, and Shultz did not have sufficient clout to gainsay him. Early in the New Year the U.S. Marines left. By March, the French and the Italians had gone too, and Lebanon was left to its internecine war.k

Israel made a second unilateral withdrawal in June 1985. The IDF pulled back all the way to the border, save for a lingering presence, varying over the following fifteen years from dozens to hundreds of soldiers, who operated alongside the South Lebanese Army militia in a narrow security zone.

Sharon blamed America for the failure of the treaty. “They don’t want to give Israel its full achievements from the war,” he told a party audience in Tiberias in April 1983, days before Shultz’s arrival on his shuttle mission. But he blamed Israel, too. “No nation can survive,” he pronounced, “if it kowtows to others; even to a superpower.”

At cabinet, where he now sat in the empty role of minister without portfolio, Sharon attacked his successor at Defense, Moshe Arens, for climbing down over the surveillance stations. When the draft agreement with Lebanon came up for approval, Sharon let loose such a stream of vituperation—“treachery” and “cowardice” were the milder epithets—that even the depressed Begin summoned the strength to upbraid him. He lashed out at General Abrasha Tamir, formerly his close military aide, who headed the Israeli military team at the talks with Lebanon. “You are bringing disaster upon this country,” Sharon shouted. Tamir ignored him. The cabinet voted 17 to 2 to endorse the agreement. Later, Sharon attacked the government for acceding to American requests that Israel delay withdrawing from the Shouf.

When Yitzhak Rabin, as defense minister in the 1984–1988 Likud-Labor unity government, proposed the June 1985 withdrawal, Sharon attacked again. The army should stay where it was on the Awali, he maintained, though with fewer troops. “Look Who’s Talking” was the columnist Yoel Marcus’s headline:

One might have expected Messrs. Shamir and Sharon to stand, heads bowed, tears in their eyes, at the funerals of the latest Lebanon victims. One might have expected them to do what Begin never had the guts to do—take a day in the week to comfort the thousands of disabled soldiers who gave their arms, legs, eyes to this war. But these two gentlemen don’t like standing face-to-face with the living or dead evidence of their acts and omissions … They stand on the ruins of their pointless, pathetic pipe dream, and they have the nerve to be dissatisfied with the efforts that Rabin and Peres are making to get us out of there.54

a The IDF force deployed in the central and eastern sectors comprised some 35,000 men and 800 tanks. Another 22,000 men and 220 tanks fought in the west. Syrian forces in Lebanon on the eve of the war, according to Bregman, numbered some 30,000 men, 600-plus tanks, and 300-odd artillery pieces. More troops were brought in after the fighting began. The PLO had 15,000 full-time fighting men and additional militiamen recruited from among the refugees. They had only 100-odd tanks but 350 artillery pieces.

b Air battles continued sporadically until the end of the week, and the Syrians lost another 51 planes, bringing the total to 87, all frontline fighters: MiG 23s, MiG 21s, and Sukhoi 22s. The IAF tally of air losses in the war was two helicopters and a Skyhawk jet downed by PLO rocket fire (Herzog, Arab-Israeli Wars, 338).

c One died, and his body was subsequently returned by the Syrians; another was captured by the Syrians and eventually returned; a third was captured and returned three years later as part of the prisoner deal with Ahmed Jibril’s Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine–General Command. Three more, Zechariah Baumel, Zvi Feldman, and Yehuda Katz, disappeared and were never found.

d In Warrior, Sharon wrote of “serious tactical mistakes and poor staff work” in the army that had resulted in episodes such as Sultan Yakub and had led to the “failure to keep the planned timetable” and reach the road before the Friday cease-fire.

e Eitan insists in his memoirs that the maps presented to the cabinet at the Saturday night meeting had arrows pointing clearly to the road. “We presented the ‘big plan,’ and the cabinet approved it. The plan explicitly included capturing a stretch of the Beirut–Damascus Road.” Eitan adds that the forty- to forty-five-kilometer line was “never part of the cabinet decision or the instructions of the General Staff to the commanders in the field … Everything was clear, and the ministers fully understood it.”

f Relations between Sharon and Habib steadily deteriorated. “As time wore on,” Sam Lewis recalled, “[Habib] became … increasingly an Israel critic, influenced no doubt by the continual Israeli shelling of Beirut. He must have been shaken at the continuing sight of smoke plumes from artillery shells and bombs from planes … The pattern of an anguished Habib reporting at great length to Washington, followed by some kind of démarche delivered either in Washington or in Jerusalem, began at the end of June and continued through the summer until the PLO finally withdrew.”

g Secretary of Defense Weinberger was far less cooperative with Shultz and Habib when it came to deploying the U.S. Marines on land. “The Palestinian forces under Syrian command wanted to turn over their positions to the Americans, not to the Lebanese army,” Shultz writes. “They feared that the Lebanese army would not be strong enough to stand up to the Khataeb, the Christian militia; they were afraid that the Khataeb would take over the PLO positions and attack the Palestinian civilians left behind … The Defense Department … did not want American forces exposed to danger in a situation of mixed command. ‘The U.S. Marines can’t just sit on their ass all the time,’ Habib howled.” Sharon wanted the MNF troops, and especially the U.S. Marines, confined to as narrow and brief an assignment as possible. Shultz could not overcome what he calls this “Sharon-Weinberger co-veto,” even though Habib warned ominously of the dangers ahead.

h Eitan, in his memoirs, acknowledges that there was “one inquiry” at cabinet “about the possibility that the Phalange would seek revenge. I responded that they [the Phalangist soldiers] appeared to be motivated to fulfill the objective of their mission, and that they had never displayed a tendency toward misconduct.” This, of course, was also a lie at the time it was purportedly said, and an even sillier lie at the time it was published, years after the Kahan Commission Report that condemned Eitan (inter alios) for precisely this disingenuousness.