Gorno-Badakhshan – 15 June 2014

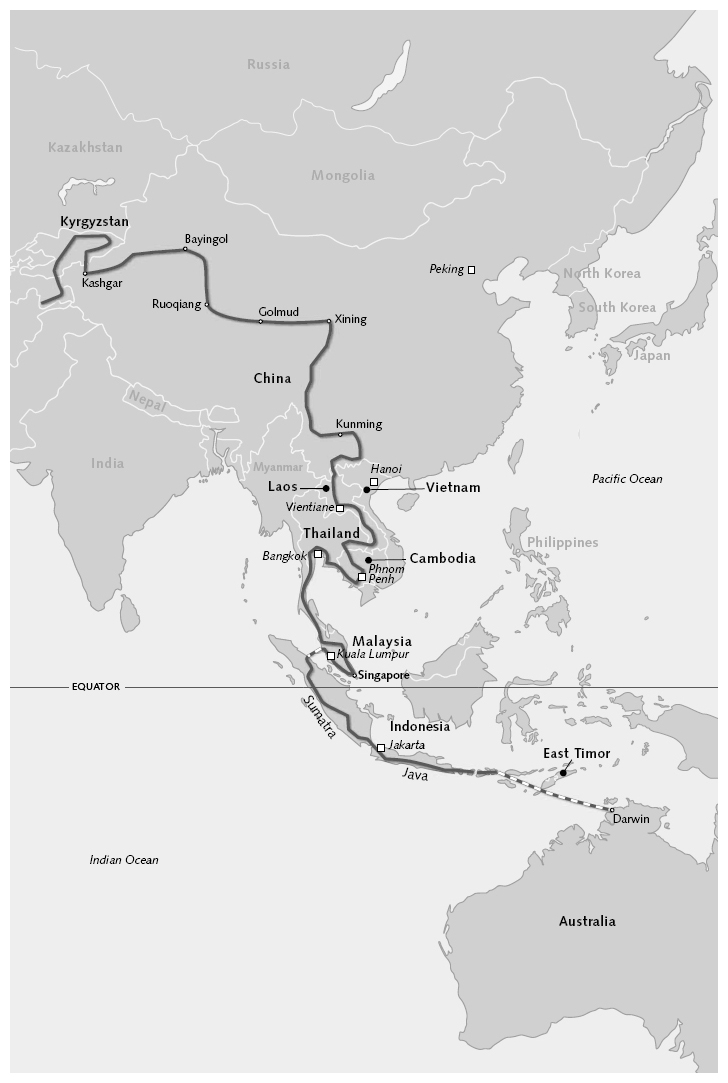

Not as old as the Silk Road, but nearly as famous, is one of its side branches: the Pamir Highway. A track of sorts had connected the remote Pamir mountain valleys with the outside world for many centuries, but its true birth date was in 1934, the year tarmac was ceremoniously laid between Khorog in Tajikistan and Osh in Kyrgyzstan, considered the end-points of this classic overland trail. Its reputation as one of our planet’s most scenic rides for cyclists, bikers and 4x4 enthusiasts is up there with other legendary routes such as the Karakorum Highway in Pakistan, the Manali to Leh road in India or the Ruta Nacional 40 in southern Argentina. To drive the Pamir Highway is the prime objective for many travellers to Central Asia. Laura and I wish to tackle it with Puck and Pixie to see if it’s really as beautiful as so many claim.

Even reaching the starting blocks in Khorog can be a challenge. Many alternative routes lead to Tajikistan’s Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region, home to the culturally distinct Pamiri people, towering Pamir peaks and a few Pamiri drug lords. We choose the Tavildara Road: the shortest by distance, but also the loftiest and least well-maintained. Soon after Laura and I leave the fertile valleys east of Dushanbe, we find ourselves toiling uphill along a dirt track between steep, ochre-coloured mountainsides, following the contours of a frothing river to its source. Initially, the gorge is wide enough to accommodate a few tiny settlements: clusters of houses surrounded by grazing pastures for goats and orchards for nut and apricot trees. The further we climb, the more the gorge narrows and the more hazardous the riding becomes. Large boulders have embedded themselves in the road’s surface, having fallen from great heights above our heads. We career around them, glancing suspiciously upwards at the weather-worn walls in case waylaying Titans are hurling more rocks at unsuspecting travellers. Of the rivers we are no less wary. In the absence of bridges, we need to ford them by plotting the shallowest course on foot, then taking the plunge with our bikes. The perpendicular surge of freezing water reaches our knees, fills our boots and almost knocks us off balance. Puck and Pixie are too heavy to be swept downstream by the strong current, but tipping over must be avoided at all cost. Unlike many 4x4s, motorcycles don’t have snorkels and the engines can flood when water enters the air-intake or exhaust pipe.

The ascent takes us above the tree and snowlines to 3,253 metres. Exhausted from our uphill jaunt, we dismount at the Sagirdasht Pass summit, heaving huge gulps of rarefied air. My lungs are noticing the altitude! Still, this pass is nothing compared to the ones we’ll encounter on the Pamir Highway. In the distance I can see the tangled knot of interlocked mountain chains of the Pamirs and the Hindu Kush in Afghanistan. For the first time since 1998, I lay eyes on a part of the world I grew to love, inhabited by people I learned to greatly admire, on my very first overland motorcycle journey. Sixteen years have passed since I toured the Pashtun-dominated provinces of Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan including Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (in the past known as the North-West Frontier Province).

Regrettably, I won’t be visiting either country this time around, to find out which of my old Pashtun acquaintances survived the invasions during the United States’ War on Terror, or War of Terror – as many civilians in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iraq see it. The American-led military campaign began three years after my visit and is still ongoing, 13 years after the attacks on the World Trade Center in New York City – the spark that ignited this tragedy and resulted in a political and humanitarian disaster. When a war lasts this long it’s sometimes forgotten by many in the West, but for those living amongst and beyond those mountains that I can glimpse from the pass, the war is still very, very real.

It strikes me as highly peculiar that everybody talks about the events of 9/11 (11 September 2001), the fateful day when 2,974 people died in the United States, but nobody acknowledges 7 October of the same year. This was when Operation “Enduring Freedom” commenced with a 44-hour non-stop aerial bombardment of Afghanistan to cripple the organisations held responsible for the terrorist act. Within the first few days of the war, 400 Afghan civilians were killed. By March the following year, the civilian death toll in Afghanistan surpassed the number of WTC casualties and reached 3,400. As we all know, the war didn’t stop there. No one knows the exact figure, but the Red Cross and Human Rights Watch agree that by April 2014 some 120,000 civilians had been killed in Iraq, 21,000 in Afghanistan and 35,000 in Pakistan. These conservative estimates don’t include indirect deaths due to inadequate healthcare, malnutrition and disease when the nations’ infrastructures fell apart. More than 176,000 individuals in total – that’s the equivalent of fifty-nine World Trade Center attacks – and yet the West memorialises the dead of 9/11 but not the civilians killed since then. Is it because they are just Afghans, Iraqis and Pashtun, not Westerners? I don’t get it. In my humble opinion, one cannot fight a War on Terror because war itself is terror.

I may not be entering Afghanistan this time around, but I can get to within a dozen metres of the border. Laura and I descend to Ishkashim in the Wakhan Valley. The village sits on the banks of the Panj, the river that demarcates the frontier between Tajikistan and Afghanistan, and then merges into the Amu Darya, once the southern inflow of the Aral Sea. We stand above the fast-flowing current and gaze musingly downstream. Aren’t rivers supposed to grow in volume over the course of their voyage? This one doesn’t. Even near its headwaters, the Panj is many times the size of the Amu Darya we camped next to in Uzbekistan’s cotton fields. On the opposite bank is Afghanistan’s Wakhan Corridor, another regional anomaly. It’s a land-bridge separating Tajikistan from Pakistan, some 300 kilometres long but in places only 16 kilometres wide. The corridor was created in the 19th century as a neutral buffer zone between Russia and British India to keep the two antagonistic empires apart.

The corridor is an annoyance for overlanders who wish to combine a Silk Road trip with a journey to India. If you could drive south from Ishkashim you’d reach the classic Hippie Trail on the southern slopes of the Hindu Kush Mountains in about an hour. Unfortunately, no road cuts directly through this remote and sparsely populated corner of Afghan territory. In order to reach Pakistan the traveller has three options: he could backtrack many thousands of kilometres and detour via Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Iran. Or he could transit China, and exit to Pakistan via the Karakorum Highway. Lastly, he could drive through Afghanistan further to the west in a military convoy to Kabul and then cross the Khyber Pass near Peshawar. It’s possible. Afghan visas and road permits are easily obtainable in Gorno-Badakhshan’s regional capital Khorog, but a transit of Afghanistan is never without risks. I’m glad I was able to experience the Hippie Trail to India when life in this region was more peaceful.

Laura and I pitch our tent in a secluded field on the side of the River Panj, take out our camping chairs, make coffee and spend the afternoon watching Afghans on the other side go about their daily business. Some Afghans are evidently doing the same, albeit seated on boulders near the embankment and presumably drinking tea instead of Nescafé. Every now and then we wave at each other and were it not for the possible mines midstream, I’d love to swim over for a chat.

The differences between this bank and the other are pronounced. Here, in contrast to the majority of Sunni Muslims in the rest of the country, we have a region inhabited by Pamiris following the Ismaili branch of Islam. This minor sect has neither clerics nor mosques, only multifunctional assembly halls and khalifas (stewards) who act as religious advisors. Women can chat freely with men on the street and the Koran’s theological interpretation is left largely up to the individual.

There, not a stone’s throw away, the situation is different. I can almost make out more minarets than private dwellings. Muezzins call loudly to prayer multiple times a day. Women walking the dusty streets are covered head to toe with burqas, and some men, with their flowing beards, look like Bin Laden’s doppelganger. Here, the political situation is wobbly, but holding. Gorno-Badakhshan enjoys a great deal of autonomy and serious revolts against the government in Dushanbe are – hopefully – now history. There, the political situation is at best unpredictable, even in the relatively peaceful Wakhan Valley.

The vista I enjoy today is one of blissful rural harmony. Locals are laying out colourful carpets on the rocks for a good wash, scrub and dry; others are toiling in the fields. Children are skinny-dipping in a shallow (and mine-free) pool, and old men wearing their woollen Pakol skullcaps are resting in the sun outside their mud-brick huts, watching the world go by. A group of Afghan youths wanders down to the Panj and casts a fishing line; I decide to follow suit from my bank and unpack my tackle from Puck’s side-box. None of us gets a bite and so, shortly after sunset, both the youths and I give each other a farewell wave, reel in our lines and call it a day. One by one, the lights go on in a nearby Pamiri village. There, in Afghanistan, all the houses remain dark: the huts and mosques have no electricity.

Our first night in the Wakhan Valley passes without any disturbances, which is surprising considering how the whole corridor is patrolled by military police on the lookout for drug-smugglers trying to cross the river under the cloak of darkness. The drug trade is a major source of income for people on both sides of the border. An estimated 100–300 metric tons of Afghan narcotics transit Tajikistan annually to meet the demands of Russia and Europe. Apparently, so we were told by Maxima and her family in Dushanbe, half a dozen lorries laden full to the brim with narcotics ply the Khorog–Russia route every year without government hindrance. If true, this might explain how the Tajik president and his mates can afford their collection of multimillion dollar dachas.

It’s not just the police who can rob you of a peaceful night’s rest when camping in the wild. The real troublemakers are intoxicated livestock herders who spot your tent at two o’clock in the morning, unzip your flap uninvited, stick their heads inside and spit slurred words into your face. That said, in all fairness to the shepherds, they’re mostly very amiable chaps when sober, more likely to share their loaf of bread and a sip of vodka with you than cause any hassle. At their best, they’ll join you for half an hour in an attempt to strike up a meaningful and friendly conversation, while their sheep, goats and cows continue to wander unaccompanied down the main road. At worst, they might plonk themselves down in front of you and your tent for an equal amount of time, and in utter silence bore their pupils into your brain without responding to greetings. My guess is that they’re bored stiff and merely want some entertainment – watching your girlfriend take a pee, for example. Poor Laura once had to wait a full hour on the verge of bursting before I was able to convince our shepherd audience to leave us alone!

During the day, unruly children are the greatest nuisance on the road. Further inland the Pamirs are effectively uninhabited, but here on the fertile banks of the Panj lies a long string of small villages where the average age of the local population seems to be about eight. When you travel by motorcycle you encounter all sorts of live and mobile road hazards, most of which display a highly predictable behaviour. Cows are safe. It seems that the processing speed of a cow’s brain is so slow it only registers your approach after you’re long gone. Horses tend to bolt, and occasionally kick out with their hind legs before they head into the fields. For this reason, bikers should pass in front of horses at all times. Sheep behave like … sheep. If the flock is divided by a road, rest assured one half will panic and dash in front of you to join their mates in the opposite field. Slow down to first gear. Canines chase bikes, but I’ve never seen a dog continue acting like a ferocious beast once coming to a halt – though it’s possible my tactic only works because I have a bag of doggie-treats in my saddlebag.

Kids – and especially boys – are a completely different ballgame. In this specific region, as soon as they hear our bikes approaching, children jump at us from behind parked cars or run screaming through garden gates into the middle of the road as if they want to get run over! Their movements are erratic and totally unpredictable. You can also never be quite sure if a child’s fist is about to open into a friendly wave or throw a rock at you. The Wakhan Valley is not Ethiopia or Lesotho, where throwing stones at foreigners is a major problem, but instances do occur here, as more than a few cyclists will attest.

The local teenage Ismaili girls, not bound by their interpretation of Islam to the same strict moral codes found in many other Islamic communities, often blow kisses towards me as I putter past schools and playgrounds. One girl, strolling through town with two of her friends in miniskirts (but all wearing headscarves), even blows Laura a huge pucker-lipped smooch, assuming at first she’s a handsome male on a motorcycle. To see the shock on her face when she realises her mistake is worth gold. While she turns crimson, her two friends crack up laughing – I can only imagine the lesbian jokes she’ll have to cope with over the coming months in class. Many aspects of Ismaili religion are relatively liberal, but same-sex relationships are not tolerated.

The remaining journey along the Afghan frontier is hassle-free. On our side we pass old forts built long ago to defend against Chinese and Afghan invaders, even older Buddhist temples and the occasional hot spring. On the far side we see Afghan youths racing us with their scooters and 100cc motorcycles. Most of the time Laura and I win – the road on our bank is in much better condition. Suddenly, our track veers away from the Wakhan Corridor and begins to rise. Ahead of us we see a gravel path winding its way upward towards imposing peaks. That’s our goal: the 4,344-metre-high Khargush Pass.

Finally, we’re out of civilisation and in the high Pamirs. No more police, no more drunken herders and no more screaming children – just mountains, nature and peace. A fox watches warily from a nearby cliff, dozens of obese marmots scuttle across a small plateau, and high above birds of prey ride the thermals. Ibex, saiga antelopes and snow leopards also roam the region but, due to illegal poaching for the Chinese market, are now exceedingly rare. Almost every part of every animal is believed to be a remedy for some ailment. The only area where the numbers of endangered animals are on the rise is in Tajikistan’s game-hunting parks. It’s no different from what I witnessed in Africa: as odd as it may sound, controlled hunting seems to be the best way to protect wildlife. When a wealthy foreigner pays $7,500 for the “privilege” of putting a bullet into a rare Marco Polo sheep, that money funds a whole array of initiatives to help the species recover – from hiring guards to deter poachers, to setting up special breeding programmes.

Just as we settle down for a lunch break, a dark cloud obscures the sun.

“That’s odd,” Laura comments, while preparing cheese sandwiches. “The cloud is reddish.”

“If we were in the Gobi I’d say there’s a sandstorm approaching,” I mumble between bites.

Looking around, I notice how the marmots are all retreating to their burrows. Perhaps it would be wise for us to do the same. At that precise moment a bolt of lightning streaks across the sky, followed by the echo of thunder between the summits. The cloud has wrapped itself around the mountains, the whispering breeze is now a wail and the temperature has dropped by a dozen degrees. Laura and I frantically pitch our tent, fighting the gale, which is trying to tear it from our grips. We’re not fast enough. Rain and hail begins to pelt us like machine-gun fire.

“Where did that come from?” Laura screams over the noise.

“Hurry!” I shout back, as water trickles coldly down the inside of my jacket. “Weigh down the pegs and stays with as many rocks as you can, then jump inside!”

Drenched to the bone we catapult ourselves into our shelter, remove our dripping socks and shirts, then zipper up into our sleeping bags. Hour after hour, Laura and I attempt to keep our home from collapsing under the pressure of the wind, sand and torrential rain, but in the end we admit defeat. All our tent’s ropes have torn from the outer cover, two of our aluminium poles have shattered and even the zips are no match for the storm.

We wait two full days before we dare to stick our heads out. All this time we can only munch on our picnic leftovers and raw instant noodles since it is impossible to ignite the stove. My very first thought as I emerge is about making a fat marmot sandwich. My second is about the condition of our tent. Inside, all our gear is covered in a thick layer of red dust; outside it looks like a snow leopard has gnawed on it. We patch up our tent as best we can, and as soon as the first hints of blue appear in the sky we attack the pass once again.

What we thought would be a leisurely ride up the Khargush turns into a trial for Pixie. Like humans, motorcycles need air to breathe, and Pixie apparently suffers from altitude sickness above 4,000 metres. On the straight she barely manages 30 kph; on an incline of more than a few degrees she stalls. You can easily rectify the problem on any engine with a carburettor by fitting smaller jets, thus restoring the proper air-petrol ratio – if you have smaller jets with you, that is. Another solution would be to remove the air filter, which apart from filtering also restricts the airflow, but on a dusty road like this I’d strongly advise against it. As if this wasn’t enough, Pixie develops a leak in her fuel system. The only way Laura can pump petrol into the engine is by – literally – giving Pixie a blowjob. Every few kilometres I see my girl leaning forward, sticking the large petrol-tank breather hose into her mouth, and giving it a mighty blow to increase the pressure in the fuel-line. It works … and I bet Pixie is happy, too.

At 4,200 metres, Pixie completely gives up and can barely hold her idling speed. For the final stretch up the pass I’ll need to give Laura a tow with Puck. Luckily, I still have the spare jets from my first world trip with me in my parts box. Back then, I took Puck to 5,359 metres on the Khardungla Pass in Ladakh, India, one of the highest motorable roads in the world.29

We finally manage to get up, over and down again, and soon reach the pristine tarmac of the Pamir Highway. Laura and I dismount to kiss it. In addition to local traffic, the route attracts a fair deal of tourism. In summer, not a day passes when one doesn’t encounter a dozen or so foreigners on bicycles, motorcycles and 4x4s overlanding to or from Europe via Central Asia. The reasons become immediately obvious: the Pamir Highway’s reputation as one of our planet’s most scenic rides is justified. Just as the Anzob Tunnel of Death was the worst, this is perhaps the most beautiful road I’ve ever seen. At an altitude never descending below 3,500 metres, it bisects barren deserts, wide plateaus and in summer, green alluvial plains dotted with yaks and yurts. Dramatic peaks, reaching more than double the height of the valley, surround the highway on all sides, feeding numerous lakes with glacial rivers.

It’s true that life here is not for the faint-hearted – even Marco Polo complained bitterly of the cold and desolation when he journeyed through the Pamirs in 1274. He deemed it highly unlikely that anybody in their right mind would ever want to settle here, but he was wrong. There is one town of significance along the highway. Murgab, a former military post established in 1893 so Russia could keep an eye on the Afghans and Chinese, today has 7,000 inhabitants. We need to stock up on food and fuel for the final few hundred kilometres to the Kyrgyz border. Both are available, but at inflated prices, of course. Not much grows at these altitudes and everything must be brought in, either from Khorog or imported from Osh in Kyrgyzstan.

In the remote parts of Tajikistan, filling up with petrol is rarely as simple as sticking a nozzle in your tank, paying and saying goodbye. Instead, one must first find a local with a barrel of diluted fuel and a bucket in his backyard, and then accept his invitation for lunch. The gentleman who owns Murgab’s petrol depot leads us behind his shed of fuel barrels into his humble abode, where his wife and mother are already setting the carpet. Laid out in front of us is a massive pot of rice pudding – or at least the Tajik equivalent – with a kilogram of semi-melted yak butter as a topping. There’s also some bread and a hot beverage the colour of greasy chicken-broth. It emits a slightly rancid smell and I recognise it immediately: it’s salty butter tea!

Putting it mildly, butter tea is a distinctly acquired taste. As with Vegemite and Marmite – the famous yeast-extract bread-spreads – many Europeans hate it. Butter is for bread and salt for sprinkling over fried eggs, right? Not here. I can’t wait to see Laura’s expression when she tries it for the first time. I know butter tea from Mongolia and, oddly, I love the taste. Maybe that’s not so strange after all: I’m also passionate about Vegemite.

Laura sips, her eyes grow wide, and to my surprise, she grins from ear to ear. “Chris! This is fantastic! Ask if we can pour ourselves more.”

Maybe her taste buds have been deprived of sensory input for so long, anything un-plov-like is a culinary delight. Either that or I have a very unusual Italian girlfriend.

Our bellies full of butter and our tanks full of fuel, we leave Murgab and steer due north. Ahead lie more passes, including the 4,655-metre Ak-Baital, which is higher than Monte Rosa on the Swiss/Italian border. Soon the road swings towards the Chinese frontier, protected by a barbed-wire fence stretching as far as the eye can see. We step through a gap in the mesh.

“We’ve made it to China!” both of us sing out in unison.

Our delight is short-lived. On our way to Kara-Kul, the highest lake in Central Asia, it begins to snow. Breathing out plumes of mist, I watch with disbelief as the display on my thermometer plummets far below zero. We set up camp on the shore, count the ice floes bobbing about in the water and dream of palm-studded beaches in Thailand. I have nothing against cold weather per se, but this is June. Having to scrape ice off your visor on the longest day of the year is just plain wrong. Enough is enough; time to descend to lower altitudes. The problem is we can’t, at least not in this part of the Pamirs. Kara-Kul, four kilometres above sea level, is as low as it gets.

We will be able to in Kyrgyzstan. The following morning we make a beeline for the border. A slow bee, admittedly, since Laura’s bike can’t accelerate past first gear. On the positive side, our pace allows us to enjoy the marvellous mountain scenery at leisure, one last time. It’s unlikely Laura and I will ever travel through the Pamirs again on a motorcycle. The border guards, dressed in full winter gear, are standing sentry behind the barrier with bemused smiles as I putter to a halt, Pixie in tow. Our passports are stamped, Laura impresses the officials with a (Pixie) blowjob, and we both set off past the flagpole and statue of an ibex that identify the frontier. From here onward it’s all downhill. A warm sun, a flush of green and a trickling brook welcome us in the valley – Laura and I dismount, kick off our boots and throw ourselves into the lush grass. Made it.

As Arthur C. Clarke wrote in Rama II: “Just being alive is not the most important thing. Life must have quality to be worthwhile. And to have quality, we must be willing to take a few risks.” I’d tend to agree. And on this note, farewell Tajikistan, and thanks for some quality adventures!

I may not have hooked dinner on the River Panj, but sitting for hours on its banks did give me time to think. Laura always seems slightly disappointed when I return trout-less after a whole day of casting and reeling, but for me, the fish itself is not central to the activity of fishing. What I really want to hook are thoughts (although a fat, tasty trout wouldn’t go amiss), and sitting immobile for hours – under the pretext of doing something useful – is a great way to meditate. All I really did that afternoon on the River Panj was allow my mind to wander as I gazed past my fishing float towards the Wakhan Corridor. Somehow, it wandered back to 1998 and my first encounter with the proud Pashtun people, whose demographic domain unfortunately lies along the troublesome Pakistan/Afghanistan frontier, stretching far into both countries.

Nowadays, if I were to tell my friends and family I was going there the reaction would be, “You’re going bloody where?!” For many, the Stan suffix alone is sufficient to conjure up in people’s minds images of suicide bombers, terrorists and drone strikes. It wasn’t always that way. Back in 1998, Pakistan hadn’t yet been stigmatised by the West as a terrorist-supporting state, and travel through the region was much safer than it is today. Even Afghanistan was doable with your own vehicle, if you were street-wise and knew which areas to avoid.30 One didn’t need armed military escorts between Taftan and Quetta or when crossing the Khyber Pass. Whether you were heading through the Chitral, Hunza or the Swiss-like Swat Valley to Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (formerly called the North-West Frontier Province), Gilgit or Skardu to hike around K2, tourism was written big! The only area where cyclists and motorcyclists ducked for cover was in the District of Kohistan along the Karakorum Highway, notorious – then and now – for rock-throwing children.

I wish I could show you what travel in the region was like before the War on Terror started. Maybe there’s a way. If you’re into reading science fiction you’re probably waiting for the day when somebody invents time machines and teleporters. I believe they already exist. In fact, right now you’re holding one such device in your hands: this book. Every travelogue or memoir sends the reader to a particular place at a specified time in history, and at this precise moment, you are sitting on the River Panj without a fish. Sorry about that.

Luckily, I still have all my diaries from my first overland journey. So if you care to join me, take a seat in the time machine. We’ll set the dial to June 1998, warp south of the Hindu Kush and see what happens.

When the dominant ethnic group of a region owns the copyright to “revenge is a dish best served cold”, I wouldn’t advise visitors to flirt with local women when passing through. I wrongly assumed this was a British saying, popularised by Gene Roddenberry who accredited the proverb to the warlike Klingons in Star Trek. Turns out it was first coined by the Pashtun tribe, and the border zone between Afghanistan and Pakistan, which I’m skirting on my motorcycle, is their home.

I needn’t have worried about offending jealous local men. Women are almost never to be seen on the whole ride from Quetta to Peshawar, a journey of more than 800 kilometres. Only on rare occasions do I catch sight of a few dark silhouettes peering out from behind half-open shutters or doorways, which tend to slam shut as soon as I putter by.

You see, Pashtun adhere to a code of honour called Pashtunwali, which is a strict set of tribal rulings permeating every aspect of daily life and is deeply embedded in their culture and history. The best-known of these laws in the West – the ones on which our media usually focuses – are those called purdah (from the Persian word for curtain), which govern gender boundaries. It’s no great secret that the severe requirements laid out for women imply that she’ll not be seen strutting down a catwalk at a Pashtun fashion show anytime soon. In this regard Pashtunwali resembles Sharia Law, albeit with the difference that the former is seen as a manmade construct that places emphasis on preserving family honour. Sharia, however, is viewed by many as a divine ruling one must follow to fulfil God’s will. Both require women to veil themselves, in some regions with a head-to-toe burqa, locally known as a “chaderi” or “parruney”. If she needs to run errands – for example to shop at the bazaar or visit the doctor’s – she may do so accompanied by a male relative or her husband. Otherwise, most of her life is spent indoors, and travellers to the Pakistani Tribal Areas will usually only glimpse female spectres. In this corner of the world, lady ghosts wear black or blue bedsheets.

Thus I’m surprised when I check into a locally run hostel near Peshawar, tired after a long day’s ride, and am immediately pounced upon by a young Pashtun girl, clad no differently from your average eight-year-old in Europe.

“What’s your name where do you come from why you alone do you have pen?” she babbles in one breath, in quite remarkable English, albeit without the use of punctuation. Luckily, the hotel owner Arman, the girl’s father, soon comes to my rescue. He’s a tall individual with stern features, dressed in a flowing grey garment – and he’s carrying a rifle.

“I see you have already met my youngest,” he smiles warmly from behind his fist-sized beard, a convention required of all Pashtun men. “She learned to speak English from all the foreigners who stay here. Welcome to my hostel.”

I want to ask what use this would be to her when she grows up, since the only profession – if any – she’ll probably be allowed to follow, is a job in the medical sector, but I decide not to question his society’s customs the moment I arrive. It’s not wise to argue with a man holding a gun – even more so when he’s an ardent Taliban supporter, as are many of the 50 million Pashtun.

The Taliban, in power now for two years in the neighbouring Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is receiving assistance in the form of money, arms and military training from many nations around the world, but first and foremost from Islamabad. Some sources claim that almost 40% of the Taliban’s regular militia is comprised of Pakistani Pashtun. This isn’t surprising. Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) helped found the Taliban in 1994, in order to create a government in Afghanistan favourable to Islamabad. From the beginnings until 1999, an estimated 80,000–100,000 Pakistanis fought in Afghanistan on the side of the Taliban against the forces of Ahmad Shah Massoud.

After 30 years of foreign invasions and the local warlords’ incessant infighting, people believe the Taliban might restore law, order and unity to “Pashtunistan”. These laws are extremely conservative, fundamentalist and harsh, and are neither open for debate nor always consistent with traditional Pashtun values, but maybe they can provide stability. This is, at least, Arman’s view. His loyalty is to God, his family, his clan and – if necessary – the Taliban.

I am a little worried about how stable this stability is, not just in Pashtun territory but in all of Pakistan. India recently developed and tested five nuclear warheads. In response, Islamabad detonated six home-grown atomic bombs at the Chagai testing site last week. Everybody in the country is still celebrating “Pakistan’s finest hour”, as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs describes it, for becoming the first Islamic state with nuclear weapons. Apart from me, that is. I don’t feel like rejoicing about an atomic bomb. So a few days later, after a scrumptious lamb dinner, I ask Arman for advice. We have a ritual of sharing meals in the hostel courtyard together with his friends and extended family – though, obviously, in an exclusively male environment. The only exception is his daughter, who jumps like a ping-pong ball from one foreign guest to the next, pestering them with questions and practising her English.

“Are we safe here?” I ask.

“Of course,” he nods, as if it’s the most obvious thing in the world. “Islamabad has nothing to say in the North-West Frontier Province, India is far away and Taliban issues do not affect you. Besides, here you are under my protection,” he adds, patting his rifle.

What he means is that everybody staying at the hostel would benefit from melmastia, the Pashtunwali principle of hospitality and asylum awarded to guests in need of help. If anything were to happen to us he would dish out badal, meaning revenge. And yes, it would be served cold. Strange that our media skips over this amazing aspect of the Pashtun value-system: how many hostel owners in the West would readily lay down their lives for a guest?

Reassured, I stay in Pakistan a total of 87 days. The weather is glorious, the scenery magical and the people – with a few exceptions – gems. From Peshawar I explore the hills, mountains and valleys to the north with my motorcycle, and visit Afghanistan via the Khyber Pass and Torkham. Almost everywhere I venture, villagers invite me for meals and bottomless cups of tea. As long as I adhere to a few simple rules of engagement (which equally apply, I believe, when visiting any culture), I’m treated like a khan. The most important is: “Foreigner, hold your tongue!” The Pashtun don’t take kindly to Westerners lecturing them. To criticise their ideologies, religion or customs is not advisable. In my experience, the best approach is to behave as a scholar in a classroom: listen, learn and show respect for your teachers. If you have a question, choose your words with caution in order not to offend. If you’re required to answer, be humble in your response. This doesn’t mean you need to lie; just be diplomatic.

When asked about your religion, the answer, “In my country, most are Christian, but I have the greatest respect for the teachings of Allah’s Prophet Mohammad,” fares better than, “I believe that we can only be saved by Jesus!”

When asked what you think of the Taliban movement, the answer, “Forgive me, but I am merely a guest in your beautiful country. Only you should decide what is best for your clan and your family,” is a wiser approach than to say, “I think they’re bloody terrorists!” This is especially advisable when your host supports the Taliban himself.

Every now and then I need to swallow hard, particularly in villages where the Taliban has greater influence and enforces a more severe form of Sharia Law. Here you can be publically beaten just for missing prayer times. To the dismay of many Pashtun – loyal to the Taliban or not – bans sometimes outlaw television sets, the playing of games or listening to popular music. The TVs and radios in some teahouses have now been replaced by bird cages, but in most areas I visit this remains the exception, never the rule.

One item not prohibited by the Taliban or the Pashtun is weaponry. Almost everyone I meet has a firearm. Gun ownership is a cultural requirement and a sign of honour. In good times and bad times, they have their uses. When riding through the province, I see groups gathered in the street, joyfully pumping ten rounds of ammunition into the sun. They are celebrating; perhaps a wedding, a nuclear bomb, the birth of a boy or simply because it’s such a beautiful day. You may also fire a bullet into the sky at the doorstep of a girl’s house while shouting out her name. This tradition, called ghagh, is a notification for the girl’s family that she can only be married to the person firing the shot.31 Some of these weapons are leftovers from the 1980s, when the United States sent nearly 65,000 metric tons of ordnance every year to those fighting the Soviets in Afghanistan, but most are locally made, crafted in a village just an hour’s ride south of Peshawar – Darra Adam Khel, which is devoted almost entirely to the gun trade.

Darra has a special aura. Locals and expats often come here to window shop, Afghans stock up on supplies for whatever conflict they’re currently involved in, and even a handful of tourists can usually be seen hanging about. Some visit out of curiosity, others for a burst of adrenalin, a few to have their photo taken holding a grenade launcher, and some to test-fire a Kalashnikov into the surrounding sandstone hills. Yet Darra is by no means an amusement park. Here they clone weapons meant for use, not for tourists wanting to impress friends at home with Rambo-style snapshots. Within a matter of days, a Darra gunsmith can manufacture a precise replica of almost any gun given to him. It’s joked that if you give them an atomic bomb, they will have a duplicate ready by week’s end.

Seated in a small workshop sipping tea, I watch with amazement as a boy no older than 12 operates a primitive lathe to drill out the barrel of a Beretta. When finished, it will sell for 20,000 Pakistani rupees, or about $200. If you don’t have that kind of money, you can purchase bargain revolvers for a tenth of that price. On the walls around me I see an assortment of ordnance sufficient to arm a battalion of mercenaries. In the corners near the workbenches lie haphazard piles of raw material: cut lengths of railway-track rails, car parts and iron rods. Darra is not a high-tech manufacturing facility, but consists of some 2,000 family-run businesses, operating from ramshackle arcades lining the town’s main street. The boy’s father passes me two Glock pistols, one original, one a facsimile. I can’t tell them apart.

“If you want some target practice, we can go outside. You don’t need to be afraid,” the boy offers.

I am, despite his reassurances. I don’t want to test a newly created weapon, just in case the craftsman made a booby.

Back at the hostel, I make preparations for my departure. Thanking Arman for his wonderful hospitality, I pass my warmest regards on to his wife – whom I never saw – and wish his family a bright future before we embrace with a huge bear hug. A tear is rolling down his cheek. Even Taliban loyalists sometimes cry.

“Wait,” he says. “I have a goodbye present for you.” A minute later he returns with a pen. “In case you are ever in danger, use this.”

At first I think he wants me to poke out an assailant’s eye with it, but no – the pen is actually a miniature pistol, like something out of a James Bond film. Arman shows me how to unscrew the body, remove the ink cartridge, insert the bullet and reassemble it. The firing pin is simultaneously the pen’s plunger. Instead of “clicking” it, you pull it out. The trigger is activated by pressing the shirt-clip. They come in three versions, I’m told: $10, $20 and $30 models.

“You don’t want the $10 one; they can explode in your hand. This is the quality model from Darra. And you can even write me a postcard with it.”

I never manage to say farewell to his daughter. One day she’s playing with guests and toying with the motorcycle keys strapped around my neck, the next she’s gone. Arman explains that she has “become a woman” and no longer wants to behave like a little girl. According to him, she’s now immensely proud that she can take on the responsibilities of a grown-up by joining her mother in the kitchen. I remain silent and keep my thoughts to myself. I’ll miss her giggling; in conservative Pashtun society it’s considered “unwomanly” for females to laugh out loud in public.

Welcome back to 2014 and a fishless evening in Wakhan Valley. Did you enjoy the time-travel? Admittedly, the atmosphere on the frontier was a bit Wild-Westish 16 years ago, but at least travellers didn’t need to fear drone strikes or local suicide bombers. Overall, I felt protected and safe. Today, one needs a special permit from the Pakistani Home Department to visit Peshawar, the Tribal Areas are effectively off-limits and even access to the serene Swat Valley was barred until recently due to a large-scale military offensive against the Taliban.

Maybe you understand my melancholy better now as I gaze southward. How sad that such remarkable people, with such an incredible culture, residing in such a harsh yet spectacular region, need to deal with so many hardships. It is their great misfortune that they live in an area that has been strategically significant in geopolitics throughout the ages, and that as a consequence of repeated invasions, the concepts of melmastia or badal as a means to survive evolved in the first place. How much nicer would life be if guests didn’t require protection and notions of revenge were obsolete?

Arman was wrong with his deluded belief that “everything will get better, now that the Taliban are in control.” The Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan ceased to exist in 2001 and became the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, with Hamid Karzai installed as president. Ever since, there have been insurgencies followed by drone strikes.32 Between 2007 and 2012 alone there were 186 suicide attacks in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. I do hope Arman, his daughter and all my other Pashtun acquaintances survived. Whatever personal views I might have on the political opinions some held at the time, I can’t help but think of them first and foremost as people … fathers and mothers with families who welcomed me into their homes.

This world is a fragile place and the pace at which it changes can be frightening. Little did Laura and I know on the last leg of our trip in Matilda that the Arab Spring was about to destabilise the whole region from Morocco to Yemen, and revolutions would topple many regimes. Neither did we envisage Syria descending into civil war when we passed through in May 2010. We were amongst the very last overlanders to have the privilege of visiting the amazing historical sites of ancient Palmyra, Aleppo’s Great Bazaar and Damascus Old Town Centre. Palmyra, with its 2,000-year-old temples and colonnades, was initially shelled and later saw iconoclastic destruction by the terrorist group known as Isis, Isil or Daesh. Aleppo’s Souq-al-Madina, the largest covered bazaar in the world, was destroyed. Damascus, the magical City of Jasmine, now lies in ruins.

Even in the last 22 months since we left Germany, the face of our planet has changed its expression. The Crimean Peninsula, formerly part of Ukraine, has been annexed by Russia. Iran’s new president, Hassan Rouhani, jump-started a new era of rapprochement with the West by phoning Washington: the first direct dialogue between American and Iranian heads of state in three decades. Meanwhile, the perception of India shifted into reverse after a spate of violent rapes, including many perpetrated against foreign tourists. Mohamed Morsi, the first democratically elected head of state in Egyptian history, was removed from office. Nelson Mandela died, as did Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez. Iraq has seen the rise of Isis jihadist insurgents, whose savage acts of violence make the Taliban seem like moderates. What appears not to have changed is the lack of international response to the actions of Israel against Palestine. In the latest offensive against Gaza, which started just days ago and is still ongoing, Israel has so far killed 1,657 Palestinian civilians, including 237 women and 438 children. The civilian death toll in Israel? Currently only two. Whether Palestine or Israel is ultimately responsible for this crisis, it’s still a bit like children throwing rocks at a tank: those living in the occupied territories don’t stand a chance.

In the end, there remains only one thing we as travellers can do: enjoy every wonder you see and every personal encounter you have to the fullest – for even if you decide to return to a much-loved destination or visit a group of people again in the future, you’ll probably never experience it in the same way.

Kyrgyzstan – 15 July 2014

It seems we made it out of Tajikistan in the nick of time. On 21 May, the day after we had left Khorog, the town witnessed a shootout between the police and three suspected drug traffickers. Two dealers were killed on the spot while the third, along with a police officer, was fatally wounded. It didn’t take long before supporters of the local drug baron and warlord Mamadbokir Mamadbokirov – who I assume has some standing in Khorog – marched on the town’s National Security Service building in protest over the police action and subsequent arrest of Mamadbokirov’s brother. The rest of the story is unclear. Witnesses loyal to Tajikistan’s government claim that the crowd, numbering about 50 demonstrators, immediately attacked the police station, lobbing a hand grenade inside, opening fire on the officers and setting the building alight. Mamadbokirov’s sympathisers state that the police initiated the violence by shooting into a crowd of 700 peacefully gathered locals. Whatever the case, Tajikistan’s central government decided to close the Pamir Highway to foreigners until peace returned.

Kyrgyzstan, often cited as the most tranquil of the “Stans”, also has its problems. On our way north from the Kyzylart border to Osh, and barely 24 hours into the country, we encounter a traffic jam stretching for many dozens of kilometres through an otherwise glorious mountain idyll. We carefully weave our way past the never-ending queue of lorries and cars. Their owners, napping in the shade of their vehicles or holding picnics on the tarmac, stare at us with envy. Towards the front of the back-up, the true nature of the disturbance reveals itself. A few hundred locals from the surrounding villages have plonked four yurts in the middle of the road along with a lorry-load of rubble for good measure. Nobody has been allowed to pass for three full days! The demonstrators are upset about the unlawful imprisonment of Akhmatbek Keldibekov, an opposition party MP native to this district. They refuse to budge until he’s released. A battalion of military police is standing guard nearby, awaiting further instructions from higher authorities. I hope the stand-off doesn’t turn ugly. Kyrgyzstan, just like every country we rode through since (and including) Azerbaijan, is essentially a pariah state. All the “Stans” have authoritarian presidents surrounded by personality cults, are reluctant to introduce economic reforms, restrict press freedom and marginalise (or ban) opposition.

Of course, I understand that nation-building isn’t an easy task, but it would be nice to see at least some real progress in the region. Most who came to power after independence are still ruling today. In Kazakhstan is President Nazarbaev, in office since 1990, presiding over a country ranking 126th out of 175 on the Corruption Perceptions Index 2014.33 His political rivals are said to have a dismal life expectancy: more than a few have been assassinated. Uzbekistan is no better off. The leader since 1991 is Islam Karimov. He’s the man ultimately responsible for the Andijon massacre in 2005, when several hundred civilians were killed by government forces during demonstrations. Emomalii Rakhmon, an alleged conspirator in the drug trade, has been the President of Tajikistan since 1994 thanks to rigged elections. Turkmenistan’s leader is Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow, who “won” re-election in 2012 with 97% of the vote. I wonder if that has something to do with his regime subsidizing electricity, natural gas and petrol. Car owners in Turkmenistan are entitled to 120 litres of free fuel a month. Hell, a pledge like that might even win you an election in the UK!

Here in Kyrgyzstan? Our current host nation is only exceptional in the sense that there have been a few leadership changes following a number of civil uprisings. These culminated in the “Osh Riots” of 2010 that left possibly more than 1,000 dead and displaced up to 400,000 people. Almazbek Atambayev is now at the helm, and if I judge him correctly, it would be sensible to give the demonstration a wide berth. But as this is the only road north from the border, we have to try and wiggle our way through. We switch off our engines and push our bikes towards the front line, where we are immediately beleaguered by the leaders of the protest. I smile politely at their speaker, a Valkyrie of a woman whose demeanour suggests she’d rather die in battle than allow us to cross.

“May we please continue to Osh? We’re tourists from Germany and very tired,” I plead.

“No! You can sleep here!” the Kyrgyz Brunhilde barks in perfect English. A grunt of approval resonates through the dense circle of onlookers. “Why do you come to our country anyway!?”

“We heard how welcoming and friendly the people of your beautiful country are towards guests, and wanted to meet you.” I see a smile or two amongst the bystanders and many nodding heads, but not the Valkyrie’s.

“No. The people do not want you to cross! You must wait until our demands are met by the government!”

I look at the crowd. It appears “pass/don’t pass” factions are slowly building, but it’s impossible to determine who’s in the majority. An elderly man gives me a pat on the back and speaks at length to the assembled. I cannot understand a word he says, but his speech has impact. Did he make an appeal to the people’s hearts and hospitality? Did he suggest that if it’s democracy they’re fighting for, one might as well begin here? Either way, the crowd parts – even the leader stands aside – and we are helped over the pile of rubble.

Thanking our lucky stars for the second time this week, we swiftly make our getaway. The best way to find tranquillity is to head into a region where the animal population exceeds that of humans – only people and their actions occasionally make life difficult and disappoint, but nature never does. When we spot the first yurts set against a backdrop of verdant hills and snow-capped mountains we know we’ve found our sanctuary. In Tajikistan the grazing season starts later, but here at lower altitudes the portable dwellings have already sprouted from the ground like poppies. In every direction there are more horses than I can count.

Still today, a thousand years after the first clans migrated into these mountains from the north, many maintain a largely nomadic lifestyle. The wandering herders drive their livestock from their winter abodes to the high pastures in May and tend to them there until late September. Few of the horses are kept for riding purposes; most are bred purely for milk and meat. It’s the nomads’ most prized animal: a good horse can fetch more than $300 at the local market. If a little extra cash is needed, a nomad’s family might provide accommodation, offer horse rentals or persuade passing tourists to hold a hunting falcon for a photo-op. During foaling season, they may sell kymys – fermented mare’s milk with an alcohol content of about 3%. It’s the national beverage and, like butter tea, an acquired taste. Laura and I pull over at a random yurt for a drink.

I’m familiar with the many customs a visitor to a nomad’s dwelling should be aware of. They’re no different from those of their distant cousins in Mongolia. Handle everything, especially food, only with the right hand; remove shoes upon entering; walk behind people sitting on the ground; when assuming your designated place on the carpet, never point your feet at anybody; and so forth. A woman of indefinable age with a chiselled, sunburnt face greets us holding a shallow piala (bowl). It’s almost as if she’d been expecting us: it already contains our desired kymys. The yurt itself is tidy and furnished with various chests, cushions and horse-tack. Fastened to the circular, wooden lattice-framework walls are many carpets and mats. They keep out the wind and cold, but also keep in the intense odours emanating from a huge pot-bellied stove positioned in the middle of the tent. As wood is scarce in the region, horse manure is used as fuel. Most of the smoke escapes through a vent in the yurt’s crown, but not all. The nomad’s abode feels like a cosy – albeit extremely smelly – canvas hobbit hole.34

We take a seat on the floor and drink. As long as one is an amiable guest, the kymys cup is bottomless – just like coffee in some American diners. It will be refilled ad infinitum, especially if you compliment the host on its wonderful taste – as every good guest should. A little dishonesty is always better than impoliteness. The woman is also keen to offer us food – two delicacies: kurat and mutton soup. The former is tooth-shattering, marble-sized balls made of strained and dried yoghurt. There’s much debate amongst overlanders whether these balls are really an edible snack for travellers – they do keep fresh for months, perhaps even years – or just a cruel culinary prank devised long ago by Genghis Khan to humiliate his enemies. Grated with a chainsaw, these marbles might suffice as a parmesan substitute in an extreme emergency, but in their current form I find them challenging to eat. I smile to our hostess as I suck on one, wondering if my gullet is sufficiently wide to swallow it whole.

The mutton soup is not as we would prepare it in Europe. It doesn’t contain any meat. Instead, pieces of sheep’s brain, tongue, offal and tail fat are swimming haphazardly in the pot. In Kyrgyzstan, they’re considered the tastiest morsels. Lean cuts are essentially dogfood, a difference also reflected in meat-market prices. A kilogram of fatty sheep tail costs multiple times the amount of a trimmed and fatless sirloin. Some of the cuts also have a symbolic meaning: it’s said that nibbling on a slice of tongue makes you a more eloquent speaker, sucking on an eyeball improves your sight, and if you want to impress your wife in bed, well …

I find one freezes less on a winter camping trip if one can focus one’s thoughts on the imagery of a tropical beach when tucking into a sleeping bag; at least this tactic of autosuggestion works for me. Hence, in a similar fashion, I conjure the taste of a divine Hungarian goulash in my mind, meditate briefly upon it and bite into a chunk of fat. Dammit! Didn’t work. I’ll have to resort to speed-eating: the less time I linger over my bowl, the less time I need suffer. In Mongolia the nomadic fare was better: there I enjoyed some of the best marinated-camel steaks on the planet. I strongly doubt a Kyrgyz restaurant will open in the West anytime soon. I’m greatly relieved once I’m allowed to perform an amin by raising my cupped hands and passing them in a downward fashion in front of my face. This is a sign of thanks and the gesture that the meal is – finally – concluded.

The locals not only do odd things with food, but also with their horses. Being a nomadic livestock herder may sound exotic to those in the West who are accustomed to a life where the only regular migration is between home and office. In reality, interspecies communication between human and sheep can be very tedious – herding is not the most exciting profession. Many nomads agree, and to alleviate boredom they’ve come up with a plethora of horseback games such as Ulak-Tartysh. Basically, this is rugby in the saddle with a decapitated goat as a ball. The general idea is to gallop full-speed towards the carcass at the beginning of the game, snatch it from the ground, carry it around a post and then dump it into a circle or old lorry-tyre. The sport never made it to the Summer Olympics. If playing with dead things is not your cup of butter tea, you could occupy the afternoon with Kyz Kuumai, an equestrian race between a boy and a girl. If he can catch her, his reward is a kiss. If he doesn’t, the girl in turn can chase him with a horsewhip. You also have Oodarysh, a wrestling match on horseback, where each contestant tries to throw the opponent from his saddle. As you can see, these are a rough people with rough customs.

Not that some of the things we do in the West would seem any less strange to the Kyrgyz nomad. Up until just over a decade ago, farmers in the Austrian region of Vorarlberg would sometimes use explosives to get rid of the bodies of cows that died on remote Alpine pastures. Fair enough, blowing up Daisy was not a fun game (though I do know some Austrian farmers who love to make things go “boom”), but a cheap and thorough means of disposing of cow carcasses. The only alternative was to airlift them by helicopter to an abattoir. Another oddity, “Cowpat-Bingo”, is played in rural areas of Germany, Austria and Switzerland. A grassy field is divided into squares, which are then marked and numbered. Participants place bets on squares by purchasing numbered tickets drawn from a hat. A cow is led into the enclosure and left to graze, while spectators watch and wait impatiently for Daisy to take a dump. The square where the first cowpat lands is the winner, and whoever holds the corresponding ticket gets the jackpot. Now explain that to a Kyrgyz nomad and see what he thinks!

What really sets the nomad and average Westerner more apart than culinary habits and sporting passions is the former’s ability to exist happily without the amenities and conveniences we take for granted. I’m not thinking of WiFi or dishwashers, but more basic requirements. Power, for example. Yurts don’t have any. Not too long ago there was a research project in Germany – “Eight Weeks Without Electricity” – that questioned the possible consequences of a long-term nationwide power failure. Could a Western country survive without international assistance? What would be the outcome if this happened in winter as opposed to summer? The result’s predictions were serious. According to the findings, our whole society would fall apart should our infrastructure, communications, banking and health systems collapse. Every societal aspect in the Western world is interconnected and ultimately dependent upon energy. Without it, our industries can’t supply petrol to filling stations and water to homes. Transport and food production/distribution would come to a halt, and emergency services such as the police, fire brigade and hospitals could not be reached by phone. Thousands upon thousands of people would probably die of exposure, illness, hunger or violence due to rioting – as well as a few teenagers who’d commit suicide when they can’t access Facebook. We’re all technology and energy addicts. The Kyrgyz nomad isn’t, and can feed himself and raise a family just fine without ever sticking a power cable into the wall. I’d be the last one to propose a full-scale return to nature – I love my laptop and the fact that I can write books with it – but it doesn’t hurt to know how to use a typewriter in an emergency.

Laura and I emerge from the yurt and return to our bikes, our clothes and hair impregnated with the aroma of horse sweat and dung smoke. Personally, I don’t find the mixture displeasing, presumably due to my love of animals and the great outdoors (or an absence of olfactory nerves). Perhaps a great business idea would be to create a line of eau de cologne body products for overlanders? Instead of Chanel No. 5, the “Traveller’s Collection” could contain batches of Engine Oil-Wet Sock Blend No. 7 or Stray Dog Drool-Campfire Blend No. 9. Even if you’re not a nomad, at least you could smell like one and enjoy a whiff of the open road.

This open road takes us to Issyk-Kul, the second largest salt-water lake in the world after the Caspian Sea, a major tourist attraction and an important location in the history of the Black Death. Most historians believe the Bubonic Plague started in China around 1330, then spread westwards to Issyk-Kul and beyond as a result of the movements of traders and the armies of Mongol khanates. Its arrival in Europe is often cited as coming from people fleeing the siege of the Genoese trading city of Caffa (today’s Feodosia) in the Crimea, during which the Mongols catapulted the corpses of those who had died from the disease into the besieged city. The consequences of this early form of biological warfare at Caffa were catastrophic. Unbeknown to the Genoese merchants who left the beleaguered city by galley, there were stowaways aboard: the Xenopsylla cheopis, or Oriental rat flea. The ships and their rats reached Sicily in 1347 and Genoa and Venice in early 1348. Over the next six years, around 45–50% of the European population died of the plague.

Today, the lake is a top tourist destination with numerous spas, resorts and hotels on its shores. Laura and I seek out a quiet spot on the northern coastline to sunbathe, wiggle our toes in the water and read a book in peace. This tranquillity is very short-lived. Barely two pages into my novel, five cars and a horse-cart pull up behind our camping chairs. Out of the vehicles emerge five families from nearby Kazakhstan: ethnic Russians on a weekend outing. They all place their beach towels within a ten-metre radius of our previously relaxing nook, stick umbrellas into the sand and begin to undress. If I may say so, there are few things on this planet less appetising than having half a dozen huge, beer-gut-bulging, hairy-backed Russian men in Speedos standing within touching distance of your chair, dripping sweat and suntan lotion on your favourite author’s novel. They are friendly chaps, though, that I will admit. One of the men offers us a bottle of Baltika-7 beer and his wife gives us a souvenir beach towel from their home city as a gift.

Those on the horse-cart are local Kyrgyz holding a picnic: three men, three women, four children and a live sheep. Why the sheep? It’s just a matter of differing customs. Americans and Europeans might take a few sandwiches and a fruit bowl on a day out to the beach; here they pack livestock. The family lays out a blanket, builds a fire-pit, pulls a woefully bleating “Dolly” from the cart, and slits its throat. Done. Now imagine trying to do THAT in Central Park in New York City when making a picnic on a Sunday! My God … envisage the mayhem: kids and teens would scream their lungs out, half the parents would die of a heart attack and the survivors would lynch you. Here, the behaviour is completely normal – the Kyrgyz kids are even having fun dissecting the carcass, looking forward to the BBQ. I’m inwardly torn between two states of mind: my left brain thinks logically, and tells me that there’s no difference between taking a sandwich stuffed with thin supermarket slices of some dead animal to the beach as opposed to doing the sandwich preparation from beginning to end on-site. The end results are identical. My right hemisphere desperately wishes they wouldn’t do the slaughtering directly behind our chairs. Guess which side wins the brain-battle? Laura and I pack up in search of less gory surroundings.

The roads in these parts aren’t the best, and the constant sand and washboard surfaces have worn away my tyres faster than I thought possible. They’ve done well – more than 20,000 kilometres since Germany – but when the inner tube appears thicker than the outer tyre it may be time for a swap. I’ve also suffered 12 punctures in the last two weeks. If I continue repairing my tube with vulcanised rubber patches it will become so thick it may be impenetrable to nails on the road.

Soon we’ll be heading to China, and getting Puck and Pixie into tiptop shape is vital. Since many repairs and purchases, such as new tyres, are only possible in a big city, we decide to return to Osh. Both of us are also in dire need of some social interaction – not with locals, no matter how friendly they are, but with people of our own tribe. It’s been a very long time since we last met travellers with whom we could philosophise over a glass of wine, chat to in our own language and laugh over jokes we understand. After extreme bouts of tribal-withdrawal, when Laura and I spot a European vehicle, we sometimes fling ourselves into the occupant’s arms, as if we were long lost relatives. In nearly every instance our warm greetings are reciprocated; this conduct is, amongst most long-term overlanders, the most natural thing in the world. Tourists on a brief holiday rarely behave in this manner. They’d be aghast if Laura and I suddenly jumped out of the bushes and embraced them while they were busy sightseeing.

We find our social watering hole at Biy Ordo Guesthouse. The place is chock-full with Western overlanders. Just as in South America or Africa, they are all dreamers with stars in their eyes and adventure in their soul. But Central Asia is still relatively new as a destination, and seems to attract a distinct breed of traveller. Dimitri, who is also staying at Biy Ordo, believes “this is where you meet all the crazy ones”. The irony is that he was referring to all the others, while in reality they don’t get much crazier than him. Dimitri is a French-American who’s on a mission to circumnavigate the globe completely under his own power. He cycles, walks and rows; buses, trains, boats and planes are not permissible. Neither are motorcycles, though we do try to convince him that Puck and Pixie could also be considered human-powered: without a twist of the wrist our bikes will go nowhere. Dimitri doesn’t buy our argument, but I think he’s just stuck on semantics. He’s doing his journey in stages over many years, and started by walking across the frozen Bering Strait from Alaska to Russia. Once he reaches Africa, Dimitri will paddle his inflatable kayak over the Atlantic: whether from Senegal to French Guyana or Namibia to Argentina remains yet to be seen. At the moment he’s waiting for the border to Tajikistan to reopen so he can cycle the Pamir Highway … with his kayak in tow!

I could tell you about the young guy who walked from Germany to Osh with his dog, and took even less time to cover the distance than we did. Or Gerome, who’s not only driving a Land Cruiser from Sydney to London, but is doing so despite the fact that he’s confined to a wheelchair. Then there’s Jordan and Magdalena who are riding Bala, their Royal Enfield, from India to Spain. Acquaintances on internet motorcycle forums keep telling them that the inherently problematic Indian-made bike will never make it. Barely a month into their journey and Bala already seems to be in her final death throes. But travel is about dreams and determination. With those two firmly in place, anything is possible. Every day in the guesthouse courtyard, all the mechanically inclined overlanders pool their combined skills together. Between beer, coffee and sandwiches, we somehow manage to jury-rig a repair so Jordan and Magdalena can set off again. Will they make it to Barcelona? Absolutely.

Within a very short period of time, we form a gang of sorts, always working together, cooking dinners for each other and sharing our opinions and intimate thoughts. Our Biker’s Club seems like a strange hybrid between Hell’s Angels and the Brady Bunch. Even some new arrivals, who initially come for a single night – such as Arjen from Holland (the only “sane” one in our group, riding a new BMW GS1200) – end up staying many weeks. The communal atmosphere is really that good. The parting, on the other hand, promises to be painful.

Michael rides into Osh on his Honda Africa Twin. Our friend from Denmark has finally caught up with us for our 60-day crossing of China. Mike’s arrival brings our Central Asian interlude to a close. It’s been a fascinating journey: environmentally beautiful, historically intriguing, culinarily disastrous and politically deplorable. Despite this, my heart desires a change of scenery. Beyond Naryn and the Torugart Pass is China, the Middle Kingdom, where everything – and I do mean everything – will be completely different.

17 76 journalists are sitting behind bars in Turkey in 2013 – more than in China or Iran. Many who were critical of the government have been charged with anti-state activities or insulting Islam.

18 McDonald’s and other international fast-food joints try to cater for local palates and offer some interesting variants to standard Western fare. Japan has McShrimp Burgers, Singapore Chicken SingaPorridge and India McAloo Tikki, a patty made of potatoes and vegetables. What you’ll never find in Islamic countries are pork-meat McRibs. And thank heavens Vietnam hasn’t created the McPuppy – yet.

19 A word of caution with regard to pasting country stickers to your motorcycle, as many travellers do. Though it’s fun to show everybody where you’ve been, make sure you never have the enemy’s emblem attached to your side-boxes. An Israeli sticker may be hazardous when riding through an Islamic country, as is often the United States’ Star-Spangled Banner. Inform yourself about your host country’s foreign relations. If you’re a football fan, the same rule applies: do not wear a yellow-red Galatasaray T-shirt when you’re in a Fenerbahçe neighbourhood in Turkey!

20 Chicken schnitzel and non-alcoholic beer to be on the safe side, just in case they are strict Muslims. If you’re from a Western country – may I ask you a favour? Next time you notice a Turkish vehicle at a motorway rest stop, offer the driver and passengers a free round of tea and sandwiches and see what happens. You might be surprised! So will they.

21 According to Sarkozy’s chief adviser, Jean-David Levitte, the discussion continued as follows:

“Hang him?” Mr Sarkozy asked.

“Why not? The Americans hanged Saddam Hussein.”

“Yes, but do you want to end up like Bush?” retorted the French President. Mr Putin was briefly lost for words, then replied, “Ah, you have scored a point there.”

22 Other sources say Juf in Switzerland or the ski-resort town of “El Pas de la Casa” in Andorra are higher. Khinalug in Azerbaijan is also a candidate, depending upon how one draws the line between Europe and Asia in the Greater Caucasus.

23 Whole books have been dedicated to this highly controversial issue. According to a survey conducted by American bathroom specialists in 2010, 74% prefer “over”. The biggest question for me remains: “Should we really care?”

24 They are fortunate not to live in Georgia with its double-Christmas celebrations.

25 Nullarbor means no trees (Latin: nullus+arbor). It’s occasionally referred to as the “Nulla-boring” by Australians due to the lack of visual stimuli when traversing the 1,200-kilometre-wide plain. One particular road section is 146 kilometres long without even the slightest kink.

26 Or virtually stationary. Polaris is not precisely north, but about 0.7 degrees out of whack. Hence, it circles the true Celestial North Pole just like every other star. However, for orientation purposes when crossing a desert, 0.7 degrees is really neither here nor there.

27 Why rough? Because the sun only rises exactly due east on two days a year: during the equinoxes. On all other days the sun will rise in a more northerly or southerly direction. Near Munich, for example, the disparity can reach ± 37°!

28 Information in this paragraph comes from the Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center, Environmental Sciences Division, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, TN; UK Consumer Council for Water; US Environmental Agency; UK Carbon Independent; UK Dept for Environment; Duke University, Durham, NC.

29 Many higher motorable passes exist in India and Tibet – for example, the 5,681-metrehigh Marsimik La or the 5,610-metre Mana Pass on the India/China border. Land Rover Matilda reached even loftier altitudes in Bolivia on the Uturuncu Mine Road. The saddle beneath the mine is at an amazing 5,768 metres, the mine itself 5,900 metres. For all record breakers, Uturuncu is currently believed to be the highest road in the world.

30 The last time Afghanistan was really safe was prior to the Soviet invasion of 1979. In the 1960s and 1970s Afghanistan was a focal point on the Hippie Trail.

31 If one introduced ghagh into our culture, it would certainly resolve all those fighting-over-girlfriend issues. However, I believe ghagh is not in line with Western legislation.

32 In case you are heading to the Pakistan/Afghanistan Frontier Zone, the US government has provided a few safety tips. If you see an aircraft circling overhead, DO NOT lie down on the ground, point at the aircraft or drop something on the road (this could be interpreted as an explosive). Any of these actions may result in the aircraft opening fire. Stay clear of anybody who might support the Taliban; they, too, will be targeted. And if you hear a buzzing noise like a lawnmower … that’s an approaching drone. The US safety tip list does not mention whether you are now allowed to lie down and cover your head or not.

33 Transparency International has published this index since 1995. New Zealand and Denmark are usually at the top (most trustworthy) with Somalia and North Korea bottom (most corruption).

34 The air vent is called a shanrak; the crownpiece is a tündük. For the Kyrgyz, the tündük symbolically represents their traditional lifestyle: it’s even depicted on their national flag. Should you fancy living in a yurt at home, you can order a locally made one for about $4,000. In some Western countries yurts are classified by the government as tents, not houses, and you might be allowed to sidestep stringent regulations and erect your dwelling on private properties not listed as building sites, such as within nature reserves.