335 S., size 14,5 × 21,0 cm, paperback with flaps

Euro 24,90 (D)/25,60 (A)

ISBN 978-3-667-10315-4

www.delius-klasing.de

E-book: 19,99 Euro

Of all possible titles, I almost decided to call this book “The Laotian Rat-Burger”. In order to explain, I must look back upon an experience in Laos, early spring 1999.

After having survived on little more than rice for weeks, I came across a small restaurant overlooking the Mekong River near the town of Vang Vieng. Advertised outside on a blackboard menu, I deciphered “Hamburgers”. For the culinary-challenged traveller spending years in remote parts of Asia, the mere mention of simple Western dishes can evoke unparalleled cravings … and so I ordered. The burger was delicious.

Upon leaving the restaurant I glanced upward to the tin roof of the establishment. There, neatly laid out in orderly rows, were dozens of large rat skins drying in the warm sun. Overcome by curiosity, I returned inside to question the waiter about the meaning of his odd rooftop collection. He replied with a single word: “Hamburgers.”

I might have felt nauseous, had they not been so irresistibly good. The following week I visited the restaurant daily to order my minced rat-in-a-bun.

The lesson learned is an important one: had I initially known the burger was rat, would I ever have ordered? Would you? Probably not. We are all severely conditioned by our upbringing and the media: Colombia is dangerous, America is the “Land of the Free”, Muslims are terrorists, “Aid for Africa” is good and rat-burgers cannot possibly be tasty. But how much of this, if any, is true? Travel has the ability to challenge your most fundamental ethical values and beliefs.

There are more risks lurking: not only will a traveller’s views of the “outer world” change, but he will spend a fair amount of his time on the road soul-searching … his own, as well as those of his fellow earthlings. Emotions become intensified, ranging from a state of blissful ecstasy to one of self-destruction. Upon returning “home”, NOTHING will appear the same as before.

This book is an account of more than eight years spent on the road in 100 different countries. My objective is to present you with questions, not answers. My hope is that you will seek these answers yourselves by undertaking your own world voyage. It’s worth it: we inhabit a wonderfully strange planet, and the days of exploration are not a thing of the past. They have only just begun.

Enjoy Your Laotian Rat-Burger. Bon Appetite!

If you prefer political correctness over observed reality, then you may find a few chapters disturbing. I call a spade a spade and let stupidity and ignorance shine where they merit mention. Thus, at times, countries and cultures – including our own – do not fare well in the following, though of course individual people will always sparkle brightly. Should your educated opinions differ from mine, they are just as valid, as long as they are based upon first-hand experiences abroad.

Important is not who is “right or wrong”, but that we express our personal truths openly and honestly. Hiding behind political correctness, patriotic dogmas, religious beliefs and social conventions will only smudge a traveller’s perspective and lead nowhere. And please also remember that this book describes our planet as I witnessed it, alongside many global events, in the time period between 2002 and 2010. It is possible that in the meantime, the world has changed – hopefully for the better.

Apropos: the “Rat-Burger” title did not tickle the taste buds of my publisher, and so my manuscript was renamed Left Beyond The Horizon. I borrowed this phrase from the tale of Peter Pan, who gave similar vague directions when asked for the route to Neverland. He points to the heavens with a smile and replies: “Second star to the right and straight on ’til morning”. Your GPS will have a hard time plotting a course with this information – as is precisely my intention. I want you to become lost. Turn right, turn left … it is of no importance. You are entering virgin territory, EVERYTHING you encounter will be new and fascinating, no matter where you turn.

Christopher Many

Winter 2015

Exploring the Zeroth Dimension

In the beginning it all seemed so ridiculously simple; there was never any doubt in your mind as to where you were in the global scheme of things. “Right there,” you had said, pricking the world map with a drawing pin slightly north of Inverness, Scotland.

…

The mathematician may classify your pinprick as a hypercube of zero dimension within Euclidean space. It resembles an infinitely small spatial point without width, length, height, edges, faces, volume, area or cells.

They can be denoted with the equation:

P = (a1, a2, …, an)

Whereby n is the dimension of the space in which the point is located.

Below is an image representing zero dimension as a point:

Curiosity (Matilda – 1 May 2002)

“This is it!” I exclaim from behind the cobweb-covered steering wheel. “I’ll buy it.”

Amidst the Scottish Highlands, near the quaint town of Fort William, stands a neglected Land Rover. The morning light on a rare rainless day does little to improve its appearance. Battered by the elements for three decades, this wonder of British engineering does not seem to be the ideal vehicle for a trip around the world. Yet, seated inside, gazing through the dusty windscreen, I hear a voice pleading: “Take me with you!”

Closer inspection reveals it will be less a matter of repair and more a question of resurrection. “Matilda”, as I named her – not in memory of a former girlfriend but after the Australian slang term for a sleeping bag – began her life as a 1975 long-wheelbase Series III military Land Rover with a 2286cc 4-cylinder petrol engine. As a member of the UK Parachute Regiment, she had been tossed out of the occasional aeroplane in her youthful years, though bombing the enemy with chute-less Land Rovers would have surely been more effective. By the mid-1980s Matilda was forced into retirement, no longer deemed fit to protect the British Isles from potential invaders. Auctioned off to a Scottish farmer, she was moved to a Highland croft; her years of “honour and glory” now rewarded with the prospect of hauling sheep between paddocks. No wonder I heard the pleading voice whispering into my ear: my first job would be to remove all the sheep shit from the rear. But for GBP 700 (around USD 1,000), what could I expect?

I quit my job with British Waterways two days after meeting Matilda. It’s a myth that a world trip requires long and careful preparation. I fail to understand why many travellers take years researching before they finally set off. One doesn’t spend months gathering information to prepare an Austrian skiing trip or a weekend in Paris – driving to Mongolia from Europe is no different. Yes, one might have a few additional borders to cross, but ultimately the procedure is identical.

“Do I have sufficient funds?” Hmm … yes. My savings should last a few years. “Passport and credit cards?” Yep, check. “Well, I guess that’s it then.” I chuck my pre-packed trekking rucksack into the back of the Landy, turn the ignition key, and leave the British Isles for Germany for final family visits and to make Matilda more “liveable”.

Sitting in my parents’ driveway, an hour south of Munich, I percolate coffee on my newly installed stove, the first of countless cups to come. Matilda’s appearance has changed considerably over the past month. With help from the local welding workshop, I’ve added a roof extension and various interior fittings. No longer is she the derelict wreck neglected in a farmer’s field, but a thing of great beauty – at least in my eyes. The only thing I seem unable to do, despite all cleaning efforts, is rid the vehicle from the lingering and pungent smell of Highland sheep. I give my parents the “Grand Tour” of my refurbished home.

“It’s a four-room house on six square metres,” I explain, folding down the hatch: “upstairs bedroom”; showing off the running water from my 40-litre tank: “kitchenette”; swivelling the collapsible table into place: “dining room”; and pointing towards the multiple storage compartments in the rear: “basement. So what do you think?”

“Where’s the bathroom?!” my mother asks bewildered. But I see by the twinkle in her eyes that she’s impressed. Matilda is approved.

Despite all intentions of making a clean break with society’s conventions, complete detachment is impossible. Medical insurance is wise to keep, likewise a postal address and Carnet de Passages for one’s vehicle in order to facilitate customs procedures worldwide. But otherwise, Matilda is neither taxed nor insured.1 I do hope I have no accidents on the road.

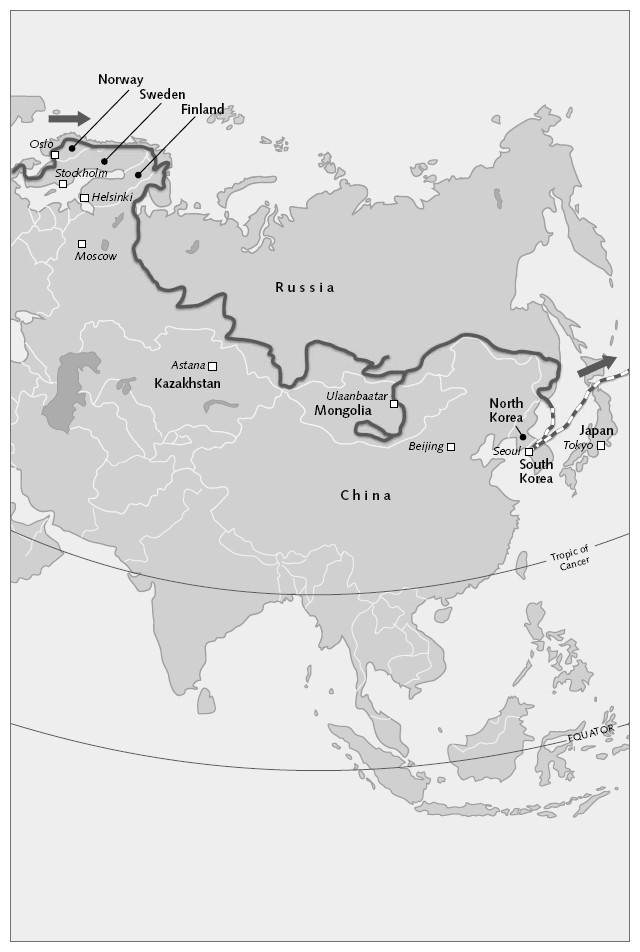

Though leaving Scotland marked the actual beginning of my trip, saying farewell to my loved-ones in Germany brought the first realisation of indefinite separation from all so dear to me. Unlike many other travellers, I’m not actually running away from Europe. I’m simply curious as to what lays beyond the horizon. I’ll be picking up Rob, a British friend of mine who’ll join me on the trip. Then we’ll turn north through Scandinavia for as far as the road will take us. Following the contours of the Norwegian coastline with its countless fjords and isles, we intend to enter Russia north of the Arctic Circle.

Standing atop a hill near Kirkenes, I have my first glimpse of Russia over the border. Grey smoke pours from a dystopian industrial site. Polluted air wafts between the cubistic concrete slabs of a grey housing project. I imagine grey people coughing their way to work, tired of a Soviet five-year plan gone horribly wrong. I pivot 180 degrees and look down at Norway. The sky is blue, homely red-painted cabins dot the beautiful scenery. “Why am I going to Russia?” I ask myself.

In the back of my head I hear the opening lines of every Star Trek episode, complete with melody, words slightly altered: “Europe – the Final Frontier. These are the voyages of the Land-Ship Matilda. Its multi-year mission: to explore strange new worlds. To seek out new life and new civilisations. To boldly go where I have not gone before.”

Comprehension (Russia Part One – 1 August 2002)

Russia is not merely big, but massive. Spanning 11 time zones,2 it is truly a country where the sun never sets. The UK, for example, would fit snugly 13 TIMES into the single Russian republic of Sakha, with room to squeeze Ireland in as well. Despite various former Soviet republics recently gaining independence, Mother Russia is still by far the largest country on the planet.

The border customs officer offers no welcoming greeting; his expression is as dour as the framed Putin hanging on the wall behind him. A few dozen forms in Cyrillic are signed, no questions asked, not that I could decipher them anyhow. For all I know I could have just conscripted myself to 10 years hard labour in some proverbial Siberian gulag. The barbed gate opens and we are waved through.

My first bleak impression of Murmansk had been from a viewpoint atop a Norwegian hill. My second impression is no better. All colours have drained from sight and greyness engulfs the entire city. A Murmansk documentary filmed in black and white would differ little from witnessed reality. Rob and I check in to the most central hotel, a drab megalith building seemingly constructed to confirm the notion that “size matters”. Its 500-plus rooms are as cubical as the building itself, and offer little more than a well-worn mattress, a naked light bulb, a stained sink and a flickering television set. We wipe a circular area clean of grime on the pane and peer through. So this is it: Welcome to Russia.

The whole idea of a Siberian vacation formed when Rob and I met for the first time in New Zealand on my previous world trip by motorcycle. It didn’t take long for us to realise how much we shared in common. Our hobbies, philosophies and interests were mostly identical. But it was our mutual passion for travel that became the strongest bond in our friendship, and when we heard that Russia was relaxing its tight control over tourism, we decided to join forces on a Russian overland journey. Prior to 2002, independent travel was difficult, with visitors restricted to a few weeks on a pre-planned itinerary with prebooked accommodation in government controlled hotels. A camping holiday was out of the question. With an atlas on our laps we had sketched a route from Murmansk to Vladivostok, deciding to avoid well-known and easy-to-visit cities such as Moscow or St Petersburg, and instead follow the northernmost route possible on a grand transit west to east. Choice of roads was made easy by the simple fact that Russia has very few once you’re passed the Urals. The thoroughfare generally follows the Trans-Siberian Railway, the main lifeline connecting remote areas to the outside world.

With an adventurer’s spirit akin to Britain’s Henry Morton Stanley, we wish to experience numerous encounters with Russia’s “natives”, previously secluded from direct contact with the West. We applied for, and received, a one-year visa for the heart of the former Soviet Union.

But first … a cup of tea. I turn the tap above the discoloured sink to watch only a rust-brown muck dribble out. Usually the first few days in a new country give you the preamble of what lies ahead. I sincerely hope this country will be an exception to the rule. Surely Russians in Murmansk have found a solution to the tea enigma. I doubt diluting the taps’ brew with vodka would make it drinkable. The answer to all our wishes sits in a hallway corner opposite the elevator door. She is massive and old, the aphorism of Mother Russia herself, and said to have a heart of gold: the maître d’hôtel and babushka responsible for our hotel’s seventh floor. She alone has the power to grant you tea, bread or clean towels. She may serve dinner and even allow prostitutes into your room. All of it depending on how much she actually likes you. My first lesson in Russia: be friendly to your babushka!

Babushkas are easy to recognise, for they all seem to have the same stocky appearance with arms the size of tree trunks and, often, a delicate moustache adorning their lips. We receive our tea in cracked cups from a sizeable samovar solely under her command

Late that night there is a persistent tapping on our door. I open to find two rather pretty girls standing outside our room, wearing very revealing clothing. I thank them profusely, decline their offer of intimate company, and return to bed with a smile on my face. It’s official: our seventh-floor babushka likes us. Murmansk itself is quickly explored. The dying Russian Fleet is sitting in the harbour, sunk not by capitalist warships but through neglect from the enemy within: a broke and corrupt government. A 40-metre-tall, reinforced-concrete statue of Alyosha – a colossal soldier commemorating the defenders of Russia’s arctic territories during the Second World War – proclaims Soviet immortality from atop a hill, waiting silently for the days of the empire to return. There is also a permanent amusement park which looks like it hasn’t amused anybody for decades. The few functioning fair rides creak precariously, perhaps too dangerous for children to enjoy, and paint is peeling form the horses of the merry-go-round. I feel a melancholic sadness sweep through me, but it’s readily replaced by euphoria once I purchase my first Russian Belomorkanal smokes: a pack of cigarettes sells for the equivalent of just seven US dollar cents in Murmansk.

We start the Landy and head south-east to the White Sea. Every town, regardless of size, has a police checkpoint at its city limits; sometimes we are waved through but more often than not we are stopped and asked to produce passports and driving licences.

“Where are you going?” they always ask.

“Vladivostok!” is always the answer.

An appreciative nod is the usual reaction. They know the distances we must cover and understand the hardships we might endure.

“Be careful,” we are warned. “Here you are safe. Once passed the Urals it becomes dangerous. The people are not like us …”

Solovetsky Island, in the White Sea, became famous through Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s book The Gulag Archipelago. The Russian novelist and historian was imprisoned at various labour camps for eight years and survived to tell the tale. We desperately want to visit the island, and after meeting an elderly Norwegian who has chartered a replica of one of Peter the Great’s sailing vessels, the Nikolai (complete with on-board cannon), we are offered a free one-way passage. How we return to the mainland will be our problem.

Setting sail from Kem harbour, we see Solovetsky Island slowly come into view. For the first time I glimpse the Russia of my dreams. Onion-domed Ortho dox Church steeples glitter golden in the sun. We spot a village of rustic log cabins and people toiling in their gardens, digging potatoes and cabbage. Fresh farm air wafts from the island’s shores over the last remaining mile of water. Soon we are sitting outside the walls of the monastery, indulging in some people watching. Gone are the dour Putinish faces of Murmansk, replaced by genuine smiles and waves of greeting. It may be true that people resemble the environment they live in.

A young stonemason, employed in restoring the monastery, invites us to his home for supper and a bottle of vodka. Or is it vodka with supper? For in Russia, vodka is the elixir of life – sometimes cheaper than water and considered the panacea for all ailments, without which life would be impossible to bear. We eat pasta and drink abundantly. Conversation held in a Russian-German-English hybrid becomes increasingly easier proportionate to the contents drained from the bottle. Unaccustomed to vodka, I feel my speech slurring, but I soldier on. If I am to spend a year in this country, I had better prepare my metabolism to cope with local customs. There is no alternative.

A few travellers have escaped Russian drinking sessions by proclaiming they are alcoholics. It works, but will also build a barrier between cultures. You will be pitied, looked upon as a sad curiosity, and never quite admitted to the inner sanctum of Russian friendship. Suffer. Get used to it. Soon enough your body will adapt. Moreover, one’s senses will belie reality, allowing Russian cities to blossom for a brief time into a multihued spring.

…

I find myself being whipped by naked sweaty monks with birch branches in a Soviet cellar. And no, this is not some perverse Russian fetish or an unorthodox orthodox method of purgatory for excessive consumption of vodka. All is completely as it should be. I’m in a Russian “banya”, the equivalent of a sauna. The fact that nudist monks – and not ordinary locals – are doing their best to exorcise my bodily demons by lashing my back with adolescent birch trees is only because we are camping at the Syktyvkar Monastery. But soon enough I can have my sweet revenge and whip my monk in return.

Visiting a banya regularly is Russian tradition, and Rob and I try to partake in the ritual at every opportunity. After some initial hesitations we find the visits rather cleansing. Birch leaves have a soothing aroma, and the whipping strengthens circulation, or so they say. And it definitely helps cure a vodka migraine! We often see women on the side of the road selling fistfuls of branches they’ve obviously picked from nearby forests. Choosing the right branches for your private banya is an art akin to inspecting a thoroughbred stallion. They should neither be too old nor the twigs too thick, or otherwise the whipping may turn sadistic.

Soon, I learn another significance of the banya. It is the epitome of the social-gathering place in most communities. One house in every dozen will usually have one, and all the neighbours communally share it. While sitting on wooden benches, stories are swapped, politics discussed and poetry recited. I assume, albeit without proof, that this is where potential built-up aggression towards annoying neighbours are vented. You just whip them harder than you usually would when it’s your turn to swing the cane. I fail to find any equivalent of community intimacy within the rest of Europe; even those of us who hold a weekly back-garden BBQ invite mostly friends, not every neighbour. Could this banya tradition work in, say, England? Would we then finally lose our hostility regarding petty issues such as “whose branches are hanging over whose fence” or “at what time our dear neighbour decides to mow his lawn”?

A few months into our journey, we are now following the Trans-Siberian Railway. Every diversion northward off the parallel running road has ended either in a dead end or peat bog. Sometimes we follow a sidetrack for hundreds of kilometres, only to find it peter out into a forestry road for timber-mill workers. But true to our initial intentions, we encounter Russians who have never met outsiders before.

On one such “road to nowhere” we cross a wide river by ferry. Our Russian has improved significantly, enabling a conversation with the ferryman. Rob has a vocabulary of 100 words, and I somewhat fewer, albeit different ones. By combined efforts, with the constant use of our dust-covered Land Rover as a drawing blackboard, we make ourselves understood.

Proudly, the ferryman shows us his ship. We descend into the bowels of the engine room, where the pistons noisily pump away, not quite camouflaging the unhealthy gnashing sound of worn ball bearings. “It’s all the fault of Gorbachev,” he explains. “He was the worst thing that could happen to Russia. We all hated him.”

This is new to me. The West considers Gorbachev an ambassador for peace, a hero, a Nobel-Prize winner – apparently, however, only because his actions were good for us, not for Russia.

“Perestroika, I know, I know. What do we have from Perestroika? Mafia, crime, corruption and no ball bearings for my ferry!”

When we reach the other side of the river, I pull out a few roubles to pay for the passage.

“No, no. For you it’s free. You’re guests in Russia; you mustn’t pay. But wait …” The ferryman disappears into his cabin and returns with a hard-boiled egg, his lunch for the day. “For you.”

The past months have humbled me to the point of humiliation. Wherever we travel, people shower us with presents, expecting nothing in return. A teenager knocks on our window at a non-functioning traffic light and hands us a cassette by the latest Russian rock band. “So you remember us,” he smiles, before turning away; a fisherman presents us with his catch of the day; a businessman from St Petersburg passes us a Russian street map CD-Rom … T-shirts, stickers and postcards are piling up in our storage boxes. When visiting someone’s home I have to be careful not to over-admire any household item as it might be offered later as a present. We give in return what we can, knowing the exchange is not in proportion. Many Russians have next to nothing. The T-shirt may be a week’s wages, the egg is more precious than a dinner invitation to the Savoy in Paris. Rural Russia only functions nowadays because the people have adapted a lifestyle of bartering. Essentially, it’s a moneyless society. Teachers are paid with farm produce from students’ families, the village mechanic might have his leaking roof repaired by a former customer and the doctor may find a pile of firewood delivered to his banya. The odd ones out are the police, disliked by all. They may not have received a government salary for months. With nothing to barter, they rely on traffic-fines and corruption as a source of income for their families.

We camp wild at roadsides behind bushes and eat our meals at “Stolovayas”, the Russian canteen-equivalent. Only two dishes are ever available, making a menu choice easy. It’s either a miniscule slab of dead cow with cabbage, or “borscht” surprise: a traditional stew with unidentifiable ingredients. Wash it down with a cup of watery Nescafé, and you are on your way again. We refill our water tanks from wells in the villages we pass through – there is always one in every street, because few houses have the luxury of running water – then head to the local kiosk to restock on edibles, an experience in itself for a first-time visitor to Russia. Entering any shop, you will find three queues of equal length. The few wares are shelved behind counters, out of a customer’s reach. At queue one, you point out the items you wish to purchase before queuing at queue two, where one is told the price and expected to pay. At queue three, you finally receive your goods. God forbid you forgot that tin of tuna; one would have to endure the whole procedure again.

Just beyond Perm-36, a former Soviet gulag and one of the last to close down in the late 1980s, an almost imperceptible incline leads through the forested Ural Mountains. Without a detailed map, we might have missed them completely. Only the slight decrease in Matilda’s speed indicates we are heading uphill. On the top stands a stone pillar: “ASIA” it reads, and on the far side “EUROPE”. We switch off the engine for a moment of solemn celebration. It seems we have already come so far, yet the distances deceive: we are still seven time zones from Vladivostok. Better get moving … a turn of the key and we roll onward, always towards the rising sun.

…

The sound of an approaching train breaks the evening silence. I watch as a long, regular row of passenger carriage lights briefly illuminates our campsite, a staccato flashing with glimpses of faces staring out from behind the windows. They too are going to Vladivostok, and in a week the passengers will be wetting their feet in the Pacific. For us, Vladivostok is still several months away.

“That was the Trans-Sib,” I tell Rob, who is busy cooking another delightful dinner from our meagre assortment of edibles. I don’t know how he does it. I look into our food box and see only potatoes, cabbage and salt. An hour of rustling in the kitchen, a call of “dinner is ready”, and behold: before me lies a vegetable lasagne complete with a starter and dessert. Magic. Either that, or Rob is wisely hiding all the goodies somewhere I can’t find them.

For days now we’ve been camping near the tracks laid over a century ago. It took 25 years for convicts and the military to complete the 9,441-kilometre line – their diaries reveal the suffering they endured:

1 No European motor insurance company provides worldwide coverage. Country-specific insurances can be taken out at every border en route. Outside of the West, this is seldom mandatory, and the traveller must decide if these insurances are worth the extra expense. Many companies in the Third World never pay out anyway if you have an accident, and even when they do, the maximum claim is often only a few hundred dollars.

2 Reduced officially from 11 to nine in 2010