LUCINDA HOLLOWAY, CARESSING BOOTH’S HAIR, HAD WATCHED him die: “[G]asping three times and crossing his hands upon his breasts, he died just as the day was breaking.” She twisted a curl of his hair between her fingers and caught Dr. Urquhart’s eye. She did not need to ask. The doctor looked up, watching for his chance when Doherty, Baker, and Conger, distracted, glanced momentarily away from the assassin’s corpse. Quicker than their eyes could detect, Urquhart’s hand, grasping a pair of razor-sharp surgical scissors, reached down for Booth’s head. In an instant he snipped a lock of the rich, black hair and pressed it into Lucinda Holloway’s palm. As quickly, she clenched her fingers around the black curl into a tight fist to conceal the precious memento. She was not a craven relic hunter who lusted morbidly, like so many others, for bloody souvenirs of the great crime. No, to her the lock was a private, romantic keepsake of the luminous, dying star. If the soldiers saw what she had done, they would have overpowered her, prying open her balled fist and confiscating her treasure.

Later, when the soldiers were gone, Lucinda entered the house and walked straight to the bookcase that held another prized relic—Booth’s field glasses. When no one was looking, she scratched her initials on the buckle of the shoulder strap, and then took the glasses to her mother’s house, a safe distance of several miles from Garrett’s farm.

THE GARRETT MEN STOOD BY AS MUTE WITNESSES TO THE drama they had helped author. By locking Booth and Herold in their barn, they made it impossible for the assassin to make a run for it when the Sixteenth New York arrived. Had they captured a notorious murderer or betrayed an injured, helpless man? Even more, a man who had come under their hospitality. Did they deserve honor or opprobrium? The Garretts feared judgment under the old Southern code. Soon, they tried to rewrite the events of this night to cast their actions in a positive light. Ignoring the fact that they evicted Booth from their home on the night of April 25, the Garretts claimed that he had declined the bed on his last night, and that it was Booth who insisted on sleeping under the porch with the sharp-toothed dogs, or in the barn on the hard, wood planks. Conveniently, they overlooked the part of the story about just who locked Booth inside that barn.

In the years ahead, they even invoked Edwin Booth’s name in defense of their family’s reputation. Edwin, a loyal Unionist, hated John’s deeds, but could not bring himself to hate his brother. Touched that the Garrett family took John in, and under the mistaken impression that they offered his misguided brother nothing but kindness and hospitality during the last two days of his life, Edwin wrote the Garretts a grateful letter: "Your family will always have our warmest thanks for your kindness to him whose madness wrought so much ill to us." If Edwin Booth had known the truth, that the Garretts had locked his brother in a barn like an animal, and helped prepare the funeral pyre, then Edwin, rather than lauding their kindness, might instead have wanted to come down to Port Royal and burn the rest of their farm down to the ground.

Edwin Booth might not have been the only one. The newspapers and the public demonized the Garrett farmhouse and gave it human characteristics, just as they had done to Ford’s Theatre. George Alfred Townsend’s lurid characterization spoke for many: “In the pale moonlight … a plain old farmhouse looked grayly through its environing locusts. It was worn and whitewashed, and two-storied, and its half-human windows glowered down upon the silent cavalrymen like watching owls which stood as sentries over some horrible secret asleep within … in this house, so peaceful by moonlight, murder had washed its spotted hands, and ministered to its satiated appetite.”

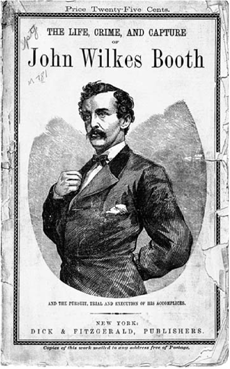

Journalist George Alfred Townsend’s

thrilling account of the manhunt.

Conger, Baker, and Doherty wanted to be absolutely certain, before they took the body back to Washington, that they had gotten their man, so they fished from their pockets carte-de-visite photos of Booth. Young Richard Garrett, mesmerized, watched the proceedings:

“I saw it done … our whole family saw it done. [H]e was a strikingly handsome man with a face one could scarcely forget. The detectives had a printed description of him which they proceeded to verify after his death. It agreed in every particular, height, color of hair, eyes, size of hand … I saw the initials J.W.B. just where they were said to be. I saw the detectives place … the photograph of John Wilkes Booth … beside the face of the dead man we had known for two days, and [nothing] in the world could not persuade me that God ever made two men so exactly alike.”

Lieutenant Doherty unrolled his scratchy, wool, regulation army blanket and ordered his men to lay Booth’s body upon it. He told the Garrett girls to go inside and bring him a thick sewing needle. Then he stitched the blanket around the assassin’s corpse, leaving one end open, like a sleeping bag, from which Booth’s feet protruded. They needed a wagon. Doherty’s men rustled up a local man and hired him to drive the corpse to Port Royal. The man brought the wagon to the Garretts’ front porch, where several soldiers heaved Booth in like a sack of corn. David Herold, whimpering, crying, pleading excuses that no one cared to hear, took it all in.

George Alfred Townsend offered his readers an unforgettable picture of Booth’s ersatz hearse:

A venerable old negro living in the vicinity had the misfortune to possess a horse. This horse was a relic of former generations, and showed by his protruding ribs the general leanness of the land. He moved in an eccentric amble, and when put upon his speed was generally run backward. To this old negro’s horse was harnessed a very shaky and absurd wagon, which rattled like approaching dissolution, and each part of it ran without any connection or correspondence with any other part. It had no tail-board, and its shafts were sharp as famine; and into this mimicry of a vehicle the murderer was to be sent to the Potomac river…. The old negro geared up his wagon by means of a fossil harness, and when it was backed to the Garrett’s porch, they laid within it the discolored corpse. The corpse was tied with ropes around the legs and made fast to the wagon sides…. So moved the cavalcade of retribution, with death in its midst, along the road to Port Royal…. All the way the blood dribbled from the corpse in a slow, incessant, sanguine exudation.

Booth’s funeral procession retraced the very route that he, David Herold, and their three young Confederate companions had followed from Port Royal to Garrett’s farm two days ago. No sobbing mourners watched this parade. The soldiers forced Herold to walk, but he complained mightily that his feet were killing him. They put him on a horse, tying his feet into the stirrups and his hands to the saddle. On the ride one of the soldiers chatted up Herold and scored a superb souvenir—he persuaded Booth’s companion to trade vests with him.

The jostling wagon disturbed Booth’s clotted wound, noted Townsend. “When the wagon started, Booth’s wound till now scarcely dribbling, began to run anew. It fell through the crack of the wagon, dripping upon the axle, and spotting the road with terrible wafers.” It was an eerie re-creation of the street scene in front of Ford’s Theatre the night of April 14, when drops of Abraham Lincoln’s blood and brains drizzled onto the mud underfoot. Townsend relished the phenomenon of Booth’s flowing blood as the stigmata of a cursed corpse: “It stained the planks and soaked the blankets; and the old negro, at a stoppage, dabbled his hand in it by mistake, he drew back instantly, with a shudder and stifled expletive, ‘Gor-r-r, dat’ll never come off in de world; it’s murderer’s blood.’ He wrung his hands, and looked imploringly at the officers, and shuddered again: ‘Gor-r-r, I wouldn’t have dat on me fur thousand, thousand dollars.’”

After Luther Baker and Ned Freeman crossed the Rappahannock, they drove Booth’s body from Port Conway toward Belle Plaine. Three miles north of that location, Baker haled the John S. Ide, which had transported the Sixteenth New York Cavalry to Belle Plaine on the twenty-fourth. There was no wharf above Belle Plaine, so Baker unloaded Booth’s corpse from Freeman’s wagon, put it in a small boat, and rowed to the Ide.

THOUSANDS AND THOUSANDS OF DOLLARS WERE EXACTLY what Conger, Baker, Doherty, and the men of the Sixteenth New York had in mind. Indeed, as news of the assassin’s death spread, manhunters across Virginia, Maryland, and the District of Columbia fantasized about the same thing: That War Department broadside dated April 20, 1865, and its astounding proclamation—“$100,000.00 REWARD! The murderer of our late, beloved President Is Still At Large.” Booth was dead. Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt, Sam Arnold, Michael O’Laughlen, Dr. Samuel A. Mudd, Ned Spangler, and David Herold had all been arrested. It was only a matter of time before the U.S. government began writing checks—to someone.

Conger’s plan worked. He had arrived in Washington before Booth’s body, and now he could claim the credit of being the first to tell Edwin Stanton the news. He rushed from the wharf to Colonel Baker’s office, where he broke the news. “He came into the back office,” Baker stated, “and said to me that he had got Booth.” Conger told the story of Garrett’s farm, unfolded his handkerchief, and showed Baker what he had—the effects taken from Booth’s body. The two detectives jumped in a buggy and, about 5:00 P.M., drove to the War Department to tell Stanton the news. But the secretary had left his office for the day. They drove on to Stanton’s home, leaped out of the buggy, and ran to the front door. They found Stanton in the parlor reclining on a lounge resting, but not asleep. “We have got Booth,” Baker told him. Stanton covered his eyes with his hands, paused, and stood up. Conger and Baker laid out Booth’s effects on a table. Stanton picked up the diary and, Baker recalled, “after looking at it for some time, he handed it back to me.” “Then,” continued Baker, Stanton picked up the “little pocket compass.” In the quiet of his parlor, Stanton had received the news—Booth had been taken, he was dead, and the manhunt for Lincoln’s assassin was over. The secretary of war wasn’t ready to celebrate yet. He wanted to be sure that the body being brought to Washington was really John Wilkes Booth. Conger unrolled the handkerchief containing the treasures he had stripped from Booth’s still living body and shared his booty with Stanton. Persuasive evidence, Stanton must have concurred, but he had to be absolutely certain. He decided to convene an inquest aboard the Montauk as soon as Booth’s body arrived in Washington. Witnesses would give notarized statements. An autopsy would be performed. Then Stanton could be sure.

In Washington, the steamer John S. Ide rendezvoused off the U.S. Navy Yard with an ironclad gunboat—the Montauk—the same vessel that Abraham and Mary Lincoln visited during their carriage ride on the afternoon of the assassination. Stanton took immediate steps to confirm the identity of the man killed at Garrett’s farm. At first glance, Booth was barely recognizable. He had shaved off his moustache, and his injury, the psychological stress of the manhunt, and twelve hard days of living mostly outdoors had taken their toll, reported Townsend, on his hitherto magnificent appearance. “It was fairly preserved, though on one side the face distorted, and looking blue-like death, and wildly bandit-like, as if bearen by avenging angels.” The War Department wanted to quash the birth of any Booth survival myths. Edwin Stanton had already scrutinized all of the personal effects collected at Garrett’s farm: the photos of the girlfriends; the pocket compass that pointed Booth south to imagined safety; the leather-bound pocket calendar. As Stanton turned the pages, he made a startling discovery—Booth had used the calendar as an impromptu diary, and in it he recorded his motive for killing Lincoln, and the turmoil of the manhunt. Only one man, Stanton knew, could have authored these fevered words: Abraham Lincoln’s assassin. Stanton announced the news to the nation:

WAR DEPARTMENT

Washington, D.C., April 27, 1865

Major General Dix, New York:

J. Wilkes Booth and Harrold were chased from the swamp in St. Mary’s county, Maryland, and pursued yesterday morning to Garrett’s farm, near Port Royal, on the Rappahannock, by Colonel Baker’s forces.

The barn in which they took refuge was fired. Booth, in making his escape, was shot through the head and killed, lingering about three hours, and Harrold taken alive.

Booth’s body and Harrold are now here.

EDWINM. STANTON

Secretary of War

News of the arrival of Booth’s body spread quickly through the capital, and hundreds of spectators rushed to the river for a glimpse of the dead assassin. “At Washington,” George Alfred Townsend reported, “high and low turned out to look on Booth. Only a few were permitted to see his corpse for purposes of recognition.” A Chicago Tribune correspondent confirmed, with palpable disappointment, that “it seems that the authorities are not inclined to give the wretched carcass the honor of meeting the public gaze.”

News of Booth’s death traveled across the nation by telegraph, and newspapers everywhere rushed to print with excited stories filled with the details of the manhunt’s climax at Garrett’s farm. As soon as the news reached Philadelphia, T. J. Hemphill of the Walnut Theatre knew what had to be done. When he called at Asia Booth Clarke’s home, she received him at once. Asia knew from the very sight of him what must have happened. “The old man stood steadying himself by the center table; he did not raise his eyes, his face was very pale and working nervously. The attitude and pallor told the news he had been deputed to convey.” Asia spoke first.

“Is it over?”

“Yes, madam.”

“Taken?” “Yes.”

“Dead?” “Yes, madam.”

Asia, pregnant with twins, collapsed onto a sofa. If one of her new babies was a boy, she had planned to name him John. “My heart beat like strong machinery, powerful and loud it seemed. I lay down with my face to the wall, thanking God solemnly, and heard the old man’s sobs choking him, heard him go out, and close the street door after him.”

On the Montauk, several men who knew Booth in life, including his doctor and dentist, were summoned aboard the ironclad to witness him in death. It was all very official. The War Department even issued an elaborate receipt to the notary who witnessed the testimony. During a careful autopsy, surgeons noted a distinctive old scar on his neck and the tattoo—“JWB”—that Booth had marked on his hand when he was a boy. The cause of death was easy to prove: gunshot via a single bullet through the neck. As proof the surgeons excised the vertebrae it had passed through and also removed part of Booth’s thorax and pickled the bone and tissue in a neatly labeled glass specimen jar. Booth’s vertebrae repose today in a little-known medical museum, one attraction among thousands in a hideous collection devoted to documenting the wounds of the American Civil War. The surgeon general’s handwritten autopsy report was clinical and brief, but betrayed the emotion of the hour. In his letter to Edwin Stanton, Dr. Barnes assured the secretary of war that John Wilkes Booth had suffered:

I have the honor to report that in compliance with your orders, assisted by Dr. Woodward, USA, I made at 2 P.M. this day, a postmortem examination of the body of J. Wilkes Booth, lying on board the Monitor Montauk off the Navy Yard.

The left leg and foot were encased in an appliance of splints and bandages, upon the removal of which, a fracture of the fibula (small bone of the leg) 3 inches above the ankle joint, accompanied by considerable ecchymosis, was discovered.

The cause of death was a gun shot wound in the neck—the ball entering just behind the sterno-cleido muscle—21½ inches above the clavicle—passing through the bony bridge of the fourth and fifth cervical vertebrae—severing the spinal chord [sic] and passing out through the body of the sterno-cleido of right side, 3 inches above the clavicle.

Paralysis of the entire body was immediate, and all the horrors of consciousness of suffering and death must have been present to the assassin during the two hours he lingered.

Stanton had decided that a written record of the autopsy was insufficient. He summoned the celebrated photographer Alexander Gardner, Mathew Brady’s rival and a favorite of President Lincoln’s, to photograph Booth’s corpse as it lay naked, stretched out on a board on the deck of the ironclad. Stanton also allowed Gardner to photograph the conspirators imprisoned on the ironclads Montauk and Saugus. Gardner took multiple images of Arnold, O’Laughlen, Spangler, Atzerodt, and Herold, each wearing an unusual type of handcuff called “Lilley irons,” joined by a solid bar that prevented the prisoners from bringing their hands together. They would see Gardner again soon, when he took their final portraits. Gardner took special interest in Lewis Powell, picturing him in a number of poses that he soon reproduced as cartes-de-visite for public sale. But, on Stanton’s orders, there would be no public viewing of the autopsy images. Harper’s Weekly based a single, discreet woodcut on one of the horrific images, but the original glass plates and paper prints of Stanton’s trophy photographs vanished 140 years ago, almost as soon as they were taken, and have never been seen again.

The prominent sculptor Clark Mills, who had recently fashioned a plaster life mask of Lincoln in March 1865, sought permission to make a death mask of his assassin. He wanted to come aboard the Montauk, slather Booth’s face with wet plaster and, once it dried, pry the mask from the assassin’s countenance. Mills went too far for the secretary of war. According to a newspaper account, “Mr. Stanton, not deeming him over loyal, replied: ‘You had better take care of your own head.’ “Death masks, Stanton perhaps reasoned, were best suited for honoring great men, not their murderers.

Stanton certainly hoped that, like the autopsy photographs, Booth’s body would vanish. Scoop-seeking reporters lusted to unearth the last great episode of the twelve-day manhunt, the disposal of the assassin’s remains.

“What,” Townsend probed Lafayette C. Baker, “have you done with the body?”

Colonel Baker uttered a typically portentous, self-dramatizing reply: “That is known to only one man living besides myself. It is gone. I will not tell you where. The only man who knows is sworn to silence. Never till the great trumpet comes shall the grave of Booth be discovered.”

“And,” Townsend confidentially advised his readers, “this is true.”

In the days following the close of the manhunt, all the major American newspapers damned John Wilkes Booth with parting epithets. The most vivid among them was penned by George Alfred Townsend:

Last night, the 27th of April, a small row boat received the carcass of the murderer; two men were in it, they carried the body off into the darkness, and out of that darkness it will never return…. In the darkness, like his great crime, may it remain forever, impalpable, invisible, nondescript, condemned to that worse than damnation,—annihilation. The river-bottom may ooze about it laden with great shot and drowning manacles. The earth may have opened to give it that silence and forgiveness which man will never give its memory. The fishes may swim around it, or the daisies grow white above it; but we shall never know. Mysterious, incomprehensible, unattainable, like the dim times through which we live and think upon as if we only dreamed them in perturbed fever, the assassin of a nation’s head rests somewhere in the elements, and that is all; but if the indignant seas or the profaned turf shall ever vomit his corpse from their recesses, and it receive humane or Christian burial from some who do not recognize it, let the last words those decaying lips ever uttered be carved above them with a dagger, to tell the history of a young and once promising life—USELESS! USELESS!

But Lafayette Baker had lied to Townsend. The second manhunt for John Wilkes Booth—the one for his corpse—had only begun. To prevent Booth’s grave from becoming a shrine, and his body a holy relic of the Lost Cause, sailors from the Montauk, accompanied by the Bakers, had pretended to row his body out to deep water and bury it at sea, so weighted down that it could never rise. The press swallowed the bait, and one newspaper, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated News, even published a front-page woodcut illustrating the faux, watery burial. What really happened was far less dramatic. Lafayette Baker, Luther Baker, and two sailors from the Montauk took Booth’s body from the gunboat and laid it on the floor of a rowboat. The sailors shoved off from the ironclad’s low-riding deck, and rowed away from the Navy Yard, down the Potomac’s eastern branch. Booth was on the river again, seven days after Thomas Jones led him to its banks. The sailors made for an army post at Greenleaf’s Point called the Old Arsenal, or the Old Penitentiary, a complex of substantial brick buildings and a courtyard surrounded by a high brick wall. They pulled in to a little wood wharf attached to the arsenal. Lafayette Baker stepped onto the wharf and, leaving his cousin in charge of the corpse, walked to the fort to find Major Benton, the ordnance officer Stanton had chosen to put Booth in the grave. Benton and Baker returned to the wharf, looked at the body, and, Luther Baker recalled, “talked the matter over.” Benton knew just the place to bury him.

Benton ordered some of his men to carry Booth’s body into the fort. They dropped it in a rectangular, wood musket crate, and screwed down the lid. Somebody wrote Booth’s name on top. Then they buried the assassin in a secret, unmarked grave at the Old Arsenal penitentiary, the site chosen by Edwin Stanton as the unconsecrated burial ground for John Wilkes Booth, and for several of his conspirators who would soon join him in the grave. Stanton kept the only key. “I gave directions that he should be interred in that place, and that the place should be kept under lock and key,” Stanton said. He wanted to be sure that “the body might not be made the subject of glorification by disloyal persons and those sympathizing with the rebellion,” or “… the instrument of rejoicing at the sacrifice of Mr. Lincoln.” Stanton wanted to keep the worshipers and relic hunters at bay: “The only object was to place his body where it could not be made an improper use of until the excitement had passed away.” Booth had escaped once before on assassination night, but he would not escape Stanton again.

Booth’s death did not end the manhunt for those who had come in contact with the assassin during his escape. If they thought Boston Corbett had saved them, they were wrong. Stanton wasn’t finished with them. His April 20 proclamation had made that clear: “All persons harboring or secreting the said persons … or aiding or assisting their concealment or escape, will be treated as accomplices in the murder of the President … and shall be subject to … the punishment of DEATH.” Stanton sent more patrols into Maryland and Virginia to track down everyone who he knew, or suspected, had seen or helped Booth during his twelve days on the run. Thomas Jones, Captain Cox, the Garrett sons, and many more were seized and taken to the Old Capitol prison. Then, curiously, within weeks, Stanton freed them all. He decided to put only eight defendants on trial—Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, David Herold, George Atzerodt, Samuel Arnold, Michael O’Laughlen, Edman Spangler, and Samuel Mudd. Not one person who helped Booth and Herold in Maryland or Virginia, aside from Dr. Mudd, was punished for aiding Lincoln’s assassin. They returned to their homes and families and, for years to come, whispered secret tales of their deeds during the great manhunt.

Several days after Booth’s burial, Luther Baker, in a coda to the manhunt, journeyed again to Garrett’s farm. It was after sunset. The charred remnants of the cedar posts, boards, and planks that had burned so brightly on the early morning of April 26 had cooled. Baker walked amidst the ruins: “Just before dark I went out to where the barn was burned, thinking I might find some remains … I poked around in the ashes and found some melted lead (it seemed he had some cartridges with him) and pieces of the blanket Herold had.”

Another hunt—the one for the reward money—began before Booth’s body cooled in the grave. With Booth dead, and his chief accomplices under arrest, awaiting trial for the murder of the president and the attempted assassination of William Seward, it was time to cash in. Hundreds of manhunters rushed to claim a portion of the $100,000 reward. Tipsters with the slightest—or no—connection to the events of April 14 to 26, 1865, angled for their rewards. Among the rival detectives, army officers, enlisted men, policemen, and citizens, the competition was brutal. Applicants exaggerated their roles, downplayed their rivals, and concocted fabulous lies to enhance their stake. In a long affidavit supporting his claim, Lafayette Baker boasted that he was the first to distribute photos of Booth, Herold, and Surratt. Lieutenant Doherty asked soldiers under his command to write affidavits to support his version of the events at Garrett’s farm.

At first, Lafayette Baker’s intrigues paid off handsomely—$17,500, an impressive sum considering that the salary of the president of the United States was $25,000. Colonel Conger got the same as Baker; Luther Baker got $5,000; and Lieutenant Doherty, commander of the Sixteenth New York Garrett’s farm patrol, got only $2,500. Together, the Baker cousins outmaneuvered their rivals and monopolized $22,500, nearly one-quarter of the entire $100,000 reward. Loud, indignant complaints forced Congress to investigate the matter. Claims were reevaluated, reports were published by the Government Printing Office, and all the while, the manhunters lobbied greedily for their money. Booth would have likely enjoyed the grotesque spectacle of this bickering for blood money over the bodies of a dead president and his assassin.

Congress adjusted the figures and finally, more than one year after the manhunt, the U.S. Treasury issued warrants to disburse the reward. Congress cut Conger’s share from $17,500 to $15,000 and raised Doherty to a more generous $5,250. But the Bakers suffered badly. Lafayette Baker, who was not present at Garrett’s farm, saw his share reduced from $17,500 to $3,750, while Luther Byron Baker’s share was cut from $5,000 to $3,000. God may have guided Boston Corbett’s hand at Garrett’s farm, but the Almighty did not intervene to line the eccentric sergeant’s pocket. He received the same payout as every enlisted man and noncommissioned officer there—$1,653.84.

Conger, Doherty, the Bakers, and the twenty-six men—two sergeants, seven corporals, and seventeen privates—from the Sixteenth New York Cavalry were not the only ones to enjoy a payday for Booth’s capture and Herold’s arrest. James O’Beirne, H. H. Wells, George Cot-tingham, and Alexander Lovett were awarded $1,000 each for their roles in the manhunt.

And then there were the other rewards. Nine men received bounties for the capture of George Atzerodt. Sergeant Zachariah Gemmill got the most—$3,598.54—and seven others won subordinate rewards of $2,878.78 each. James W. Purdum, the citizen whose tip contributed to the German’s arrest, was paid the same. Major E. R. Artman, 213th Pennsylvania Volunteers, received $1,250.

Ten claimants split the reward money set aside for the arrest of Lewis Powell. Compared with what some other manhunters received for less hazardous work, the bounty for capturing the dangerous Seward assassin was not generous. Major H. W. Smith got the most, $1,000, and the other participants—Detective Richard Morgan, Eli Devore, Charles H. Rosch, Thomas Sampson, and William Wermerskirch—were paid $500 each. Citizens John H. Kimball and P. W. Clark also received $500 each, and two women, Mary Ann Griffin and Susan Jackson—“colored”—received the smallest rewards paid to anyone who shared in the bounty, just $250 each.

The reward payments totaled $104,999.60, and the Treasury Department issued warrants “in satisfaction of all claims,” to the dissatisfaction of the many claimants—officers, soldiers, detectives, government officials, citizens, and crackpots—who dreamed of cashing in on Stanton’s April 20 proclamation, but who got nothing.

Richard Garrett also made a claim against the government, not for helping capture Booth and Herold, but for the damage that the MANHUNTERS did to his property. His inventory was extensive. Two thousand dollars for one “tobacco house … framed on heavy cedar posts, plank floor throughout … furnished with all the fixtures for curing tobacco, including prize-press and sticks for hanging tobacco.” Then there were the contents, for which Garrett demanded $2,670: “One wheat-threshing machine (150); two stoves (25); one set large dining room tables (mahogany or walnut) (50); ten walnut chairs, cushioned seats (40); one feather bed (15); one shovel (1); two axes (3); five bushels sugar-corn seed (7.50); five hundred pounds hay (10).”

In addition, Garrett wanted $21.00 for the fifteen bushels of corn and 300 pounds of hay consumed by the horses of the Sixteenth New York. The government actually considered his claim, issued an official report, and refused to pay him a cent, reasoning that he had, after all, been disloyal to the Union.

Boston Corbett did enjoy additional compensation—fame. The public celebrated him as “Lincoln’s Avenger.” Citizens deluged him with fan mail, and he faithfully answered their letters, sometimes offering biographical tidbits, religious counsel, or occasionally a coveted, firsthand account of the events at Garrett’s farm. To the delight of autograph seekers, Corbett made a point of signing these letters with his full name, rank, and unit. The following letters are typical.

Clarendon Hotel/Washington, D.C./May 61865 My dear young friend I must give you an answer for you ask so pretty. May God Bless And Protect You and keep you from the snares of the Wicked One Who so prevailed with him who took the life of Our President. The Scripture says, Resist the Devil And he will flee from you… Boston Corbett/Sergt. Co. L. 16th N.Y. Cav.

Lincoln Barracks/Washington D.C./May 11th 1865 Dear Sir, In answer to Your request I would say that Booth was Shot on the Morning of the 26th of April 1865 Near Port Royal, Virginia at which place we Crossed the Rappahannock in Pursuit. He lived but a short time after he was Shot, Perhaps 3 hours, and at about Seven O’clock that Morning he died. Yours Truly/Boston Corbett/Sergt. Co. L. 16th N.Y. Cavalry.

Incredibly, Corbett also corresponded with the assassin’s family. Corbett’s letter, long lost, its contents unknown, exists only as a shadow in Asia Booth Clarke’s memoir of her brother: “We regard Boston Corbett as our deliverer, for by his shot he saved our brother from an ignominious death…. I returned Boston Corbett’s letter to him; he did not request it exactly, but I thought it honorable to do so and safer at the time not to retain it…. He is still living, but I know he is not happy…. May he have no regret.”

Photographer Mathew Brady scored a coup over his rival Alexander Gardner. Although Gardner had won the right to photograph the conspirators in irons on the navy ironclads, and also Booth’s autopsy, Brady secured an exclusive sitting with the man of the hour. Always alert to the commercial possibilities of his art, Brady arranged Corbett in a variety of poses: seated and standing, reading a book and looking at the camera, armed and unarmed. Brady even persuaded Lieutenant Doherty to join the session for a standing, double portrait with Corbett, each man decked out in full cavalry regalia. The greater the number of poses Brady could induce Corbett to assume, the more cartes-de-visite he could sell to a besotted public. Some lucky fans even got Corbett to autograph his photo for their albums. When he appeared in public, reported one newspaper, “he has been greatly lionized, and on the streets was repeatedly surrounded by citizens, who occasionally manifested their appreciation by loud cheers.”

A few dissenting voices, including the editors of the Chicago Tribune, wondered why the men of the Sixteenth New York had to kill the assassin: “The general regret is that Booth was not taken alive, and the general disposition to complain that he might have been if a combined rush of twenty-eight men surrounding them had been made.”

The man of the hour, Booth’s killer, Boston Corbett (top). Blood money—Corbett’s share of the $100,000 reward (bottom).

Beyond the reward money, Corbett profited little from his fame. Relic hunters offered fantastic sums for his Colt revolver, up to $1,000, but he refused to part with it. It wasn’t his to sell: the weapon had been purchased by the War Department and issued to the sergeant along with his uniform, saber, and other equipment. Then, not long after he shot Booth, somebody stole it from him, and it hasn’t been seen since.

Boston Corbett was never punished for shooting Booth. He had violated no orders, and no one could prove that his true motive was anything other than protecting his men. He had the reputation of a good soldier. Luther Baker remembered that “he attended to his duties as a soldier very strictly, and seemed to have a good deal of dignity among the men.” But Baker also recalled something else about the eccentric, self-castrating, hard-fighting sergeant: “I noticed from the first that he had an odd expression.”

TWO AND A HALF MONTHS AFTER THE DEATH OF JOHN WILKES Booth at Garrett’s farm, at around 11:00 A.M. on July 6, 1865, the clock began ticking down on one of the most dramatic events in the history of Washington, the epilogue of the manhunt for Lincoln’s killers. It began when Major General Winfield Scott Hancock rode to the Old Arsenal Penitentiary, now Fort Leslie McNair, carrying four sealed envelopes from the War Department. They were addressed neatly in a clerk’s hand to four prisoners who had languished in solitary confinement at the arsenal.

Hancock handed the envelopes to Major General John F. Hartranft, commandant of the prison. Hartranft accepted the mail grimly. He suspected, without even breaking the seals, what the envelopes contained, and the unpleasant duty that awaited him. Together, Hartranft and Hancock marched to the prison building and, walking down a long corridor from cell to cell, delivered the envelopes to their recipients—Lewis Powell, Mary Surratt, David Herold, and George Atzerodt.

Torn open in fearful haste, the envelopes contained death warrants. Having been found guilty by a military commission of conspiring with John Wilkes Booth in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln and the attempted assassination of Secretary of State William Seward, the letters informed Powell, Surratt, Herold, and Atzerodt that they were to be put to death by hanging.

For the defendants, that news was bad enough, but the rest was equally shocking. By order of President Andrew Johnson, they would be hanged the next day, on July 7. Hartranft left the stunned prisoners, who had less than a day to live, to contemplate their fates. He had work to do. Did anyone at the fort know how to build a scaffold? Or how to tie a noose?

The rapid conviction, sentencing, and execution of the Lincoln assassination conspirators ended a trial that had meandered through May and June. The archfiend Booth was dead, but eight members of his supporting cast took center stage in his absence.

Johnson, under pressure by Edwin Stanton, had ordered that eight members of Booth’s supporting cast be tried by a military tribunal, a controversial move that provoked objections from Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles and Lincoln’s first attorney general, Edward Bates. The trial proceeded anyway and became the great focus for that spring and summer. By the time it was over, the commission had been in session for seven weeks, had taken the testimony of 366 witnesses and had produced a transcript of 4,900 pages.

On June 29, the commission went into secret session. After such a long and complicated trial, observers thought that it might take weeks to reach verdicts. But the end came more quickly. After deliberating just a few days, the tribunal presented the verdicts and sentences to Johnson on July 5. He approved them at once, and the next day Hancock carried the execution orders to the prison.

The residents of Washington did not know until the Evening Star came off the press on the afternoon of July 6 that four conspirators would hang the next day. Indeed, it was from the newspapers that Surratt’s attorneys learned their client would die. Newsboys rushed onto Pennsylvania Avenue, hawking the issue to eager readers: “Extra. Mrs. Surratt, Payne, Herold and Atzerodt to be Hung!! The Sentences to be Executed Tomorrow!! Mudd, Arnold, and O’Laughlin to be Imprisoned for Life! Spangler to be Imprisoned for Six Years!”

As evening passed and night fell, the news caused a flurry of activity throughout Washington. Reporters converged on the Old Arsenal, but Hartranft barred them from interviewing the condemned. Frustrated but refusing to be outwitted, the gentlemen of the press spied on the prisoners through cell windows, and recorded in their notebooks the last visits of family members and how the condemned behaved. In the courtyard, soldiers labored through the night building a scaffold while the hangman prepared four nooses from thirty-one-strand, two-thirds-inch Boston hemp, supplied by the Navy Yard.

Mrs. Surratt’s supporters, including her daughter, rushed to the Executive Mansion to beg Johnson for mercy. He would not see them or be swayed. In a daring, last-minute legal maneuver, the Surratt attorneys got a civil court judge to issue a writ of habeas corpus ordering the army to release her into civilian custody. Johnson ended her last hope by suspending the writ the next morning.

Elsewhere in Washington that night, others reveled at the news of the impending hangings. A pass to the execution—fewer than two hundred were printed—was the hottest ticket in town. Crowds besieged Hancock in the streets and at his hotel, the Metropolitan. According to the Evening Star, “his letterbox was filled with letters and cards that projected like a fan, and for a time the entrances to the hotel were completely blockaded.” Curiosity seekers needed no pass to surround Surratt’s boardinghouse on H Street. The house where the conspirators held their meetings became, in the words of one reporter, “the cynosure of hundreds of curious eyes.”

By order of President Johnson, the execution was scheduled to take place between 10:00 A.M. and 2:00 P.M., July 7. At exactly 1:02 P.M., the prisoners, with Surratt at their head, were paraded single file into the courtyard, past four pine boxes and four freshly dug graves, and up the scaffold steps. Terrified, and wearing a black alpaca dress and black veil that completely concealed her face, Mary Surratt could barely walk and needed soldiers and her priests to support her.

Lewis Powell strutted jauntily without fear, “like a king about to be crowned,” according to a reporter. David Herold and George Atzerodt shuffled along fretfully. It was a bright, blazing hot Washington summer day. Courteous officers shielded Surratt with parasols and placed a white handkerchief atop Atzerodt’s head to protect him from the sun.

The condemned were bound with strips of linen, had nooses looped around their necks and white hoods drawn over their heads. The hangman, who had come to admire Powell’s stoicism, whispered into his ear as he tightened the noose: “I want you to die quick.”

The giant who had nearly stabbed the secretary of state to death replied, “You know best.”

Surratt pleaded to those near her, “Please don’t let me fall.” When she complained that her wrists had been bound too tightly, a soldier retorted, “Well, it won’t hurt long.”

Moments before the drop, Atzerodt cried out, “God help me now! Oh! Oh! Oh!” His last word was still on his lips when, at 1:26 P.M., he and the others dropped to their deaths, a moment preserved forever by photographer Alexander Gardner, whose execution series remains the most shocking set of American historical photos ever made.

That night, a mob celebrated the execution by attacking Surratt’s boardinghouse to strip it of souvenirs, until the police drove them off. John Surratt, still hiding in Canada, read about his mother’s execution in the newspapers. He had fled the United States, arriving in Montreal on April 17. From there he traveled about thirty miles east to St. Liboire. A parish priest, Father Charles Boucher, gave sanctuary to the former Catholic seminarian, and Surratt remained there in hiding from mid-April through the trial, conviction, sentencing, and hanging of his mother. He followed the trial by reading the papers, and through secret correspondence with friends in Washington. In all that time, from the end of April to the first week of July, Surratt made no effort to save his mother from the gallows. Later, he blamed his friends for failing to inform him about the true peril that Mary Surratt faced.

Just hours after the hanging, as the bodies of the conspirators rested in the pine ammunition crates that served as coffins, the editors of the Evening Star pronounced their satisfaction with the day’s work: “The last act of the tragedy of the 19th century is ended, and the curtain dropped forever upon the lives of its actors. Payne, Herold, Atzerodt and Mrs. Surratt have paid the penalty of their awful crime…. In the bright sunlight of this summer day … the wretched criminals have been hurried into eternity; and tonight, will be hidden in despised graves, loaded with the execrations of mankind.”

Lewis Powell, David Herold, and George Azterodt, reunited in the grave with John Wilkes Booth, together again, just as they were that terrible Good Friday evening of April 1865, the night that the chase for Abraham Lincoln’s killer began.

BUT LINCOLN’S ASSASSIN HAD NOT REACHED HIS FINAL RESTing place. There remained one, final manhunt for him. February 1869 was the last month of Andrew Johnson’s troubled presidency. On March 4, the great hero of the Civil War, General Ulysses S. Grant, would take the oath of office. Soon Johnson’s name would be eclipsed, an ephemeral interlude between the old administration of the martyred Lincoln and the new one of the hero Grant. Whatever his reputation, Johnson still possessed the full executive authority of the presidency—including the pardon power—until his final day in office.

It had been almost four years since the assassination of Abraham Lincoln and the great conspiracy trial. The raw wounds of April 1865 had, at least in part, healed. Indeed, when John Surratt Jr., who had fled America after Lincoln’s murder, was captured in Europe in 1866 and brought back to the United States for trial in 1867, he was tried, not by the military tribunal that condemned his mother, but by a civil court. And, after a proceeding that produced a voluminous, two-volume transcript of 1,383 printed pages, he was freed. The passions of 1865 had subsided, and President Johnson’s thoughts turned to three of the convicted conspirators who had escaped hanging in July 1865—Dr. Samuel Mudd, Samuel Arnold, and Edman Spangler. The fourth, Michael O’Laughlen, had died in prison. Mudd and Arnold, serving life sentences, and Spangler, sentenced to six years, all languished in the American Devil’s Island, the faraway military prison at Dry Tortugas, Florida.

On February 8, 1869, President Johnson pardoned Mudd, and soon thereafter Arnold and Spangler. They had survived the manhunt, and now they were free. And, freed from the grave by an order of the president transmitted the same day, was the body of Mary Surratt. Her daughter, Anna, had her remains disinterred from the Old Arsenal and buried the next day at Washington’s Mount Olivet Cemetery.

In New York City, one man followed the news with keen interest. He had waited patiently for this day, for he, too, sought to redeem a loved one. He sat at his desk and began writing a letter to the president.

N.Y. Febry 10th, 1869

PRIVATE.

Dear Sir—

May I not now ask your kind consideration of my poor Mother’s request in relation to her son’s remains?

The bearer of this (Mr. John Weaver) is sexton of CHRIST CHURCH, Baltimore, who will observe the strictest secrecy in this matter—and you may rest assured that none in my family desire its publicity.

Unable to visit Washington I have deputed Mr. Weaver—in whom I Have the fullest Confidence, and I beg that you will not delay in ordering the body to be given to his care.

He will retain it (placing it in his vault) until such time as we can remove other members of our family to the BALTIMORE CEMETERY, and thus prevent any special notice of it.

There is also (I am told) a trunk of his at the National Hotel—which I once applied for but was refused—it being under the seal of the War Dept., it may contain relics of the poor misguided boy—which would be dear to his sorrowing mother, and of no use to anyone. Your Excellency would greatly lessen the crushing weight of grief that is hurrying my Mother to the grave by giving immediate orders for the safe delivery of the remains of John Wilkes Booth to Mr. Weaver.

Edwin Booth

Five days later, Andrew Johnson ordered the War Department, no longer the domain of the once all-powerful Edwin Stanton, to surrender the body of Lincoln’s assassin to his family. A Washington, D.C., undertaker, Harvey and Marr, picked up the body in a wagon and drove into town, and down a familiar alley to a shed behind the funeral establishment. The sturdy wood crate was unloaded and brought inside. John Wilkes Booth would have recognized the little shed. Once it was a stable, fitted out for him by a man named Ned Spangler. Booth had returned to Baptist Alley, behind Ford’s Theatre, where the manhunt began.

The Washington Evening Star remarked on the delicious irony: “It is a strange coincidence that the remains of J. Wilkes Booth should yesterday have been temporarily deposited in the stable, in the rear of Ford’s Theatre, in which he kept his horse, and fronting on the alley through which he made his escape on the night he assassinated President Lincoln. The remains were deposited in the stable by the undertakers … in order to baffle the crowd who had besieged their establishment, on F Street, to satisfy their curiosity by a sight of the body.”

From there, Edwin Booth had his brother whisked away to Baltimore, where the remains rested for the next four months in a vault at Green Mount Cemetery. On June 26, 1869, John Wilkes Booth was buried quietly in the family plot at Green Mount. No headstone marks his grave. He lies there still, his epitaph carved not on cold stone or marble, but in his sister’s forgiving heart. Asia Booth’s loving memoir to her brother closes with a graveside elegy:

“But, granting that he died in vain, yet he gave his all on earth, youth, beauty, manhood, a great human love, the certainty of excellence in his profession, a powerful brain, the strength of an athlete, health and great wealth, for ‘his cause’ This man was noble in life, he periled his immortal soul, and he was brave in death. Already his hidden remains are given Christian burial, and strangers have piled his grave with flowers.

“‘So runs the world away.’”