The world teems with clever tips about your financial life. But not all of them reveal secret loopholes in the ways businesses work. Some of the best are secret loopholes in the way you work.

Here are some of the best “self hacks” for getting more money—and spending less of it.

How to insure yourself—and save thousands

You know how insurance works, right? When you choose an insurance plan for your home, car, or health, you’re asked to choose a deductible: an amount of money you’ll have to pay in case of disaster, before the insurance kicks in. If you choose a $5,000 deductible on home insurance, then if a tree falls on your garage and causes $9,000 worth of damage, you pay the first five grand and the insurance covers the rest.

The higher the deductible you sign up for, the less the insurance costs you. Logical enough, right? If you agree to a $5,000 deductible, the homeowners insurance on a typical house might cost $2,000 a year. But if you’re willing to handle a $10,000 deductible, you’ll pay only $1,600 a year for the insurance.

Here’s the thing, though: You’ll probably never need your insurance. Most of the time, you pay and pay but get absolutely nothing tangible in return.

So here’s the tip: Call your insurance company and change your plan. Switch to a higher deductible. Pay less per month or per year.

So far, not rocket science.

The reason people don’t do that, of course, is that they’re terrified of a large deductible. They’re worried that in case of disaster, they won’t be able to afford that big chunk.

So here’s the beautiful trick: Open a new savings account. Fill it with enough money to match the higher deductible.

Now you can sleep at night, knowing that if something bad happens, you’ve got the money to cover your share.

And where do your contributions to that savings account come from? It’s from the money you would have paid to the insurance company for the more expensive plan! It’s just that now you’re paying yourself instead of the insurance company.

And if nothing bad happens? Then that money is yours to keep!

Here’s the best part: Every year or two, your “deductible savings account” will have piled up with so much money that you can revisit your policy and get an even higher deductible, and pay even less per month or year.

Basically, you’re saving money by saving money. —William Daily

Savings ballpark: $1,000 a year

$1,000 = Savings of increasing the deductible on a $1 million homeowner policy from $2,500 to $10,000

The 30-day cool-off rule

Here’s another psychological fake-out that really works: the 30-day cool-off rule.

It works like this: You’re out and about, and you see something you really want. “Wow, look at that cool Bluetooth speaker/Photoshop upgrade/cocktail dress/time-share condominium,” you might say. Your credit card hand involuntarily creeps toward your wallet.

Instead, you reach for your phone (or notepad). You don’t buy the thing; you write it down. The name of the thing, the store where you found it, the price, and the date.

You can post this growing list on your fridge, or leave it in your Notes app on the phone. And there it will sit—for 30 days.

After 30 days, if you’ve still got the urge (and the disposable income), then by all means take the plunge.

But by waiting 30 days, you’ve gained two beautiful money-saving perks:

• You’ve had the time to research the thing you wanted to buy. Maybe you’ll find a lower price or a better model. Or you’ll discover, by reading online reviews, that the product isn’t so great.

• You’ve given yourself time for the temporary aspects of the impulse to fade away: the attractively lit display in the store, the marketing exclamation points, the mood of temporary craving you were in that day.

So how is the 30-day rule different from just telling yourself, “I don’t really need that”? Because you’re much more likely to reach that conclusion if you believe that you’re just delaying the transaction instead of denying it.

As a result, the 30-day rule works. In many cases, you wind up talking yourself out of that expenditure, having realized, in the cold light of day, that it’s really not something you needed.

The overwhelming math of starting to save early

Frank is a planner. He decides to start saving for his retirement as soon as he gets his first real job, at age 25. He puts away $250 a month into a tax-deferred retirement account, like an IRA.

But 10 years later, his financial situation has changed. He doesn’t make enough to put away any more toward his retirement account. It appreciates 7 percent a year, but those 10 years of contributions—$30,000—are all he’ll ever add.

Sharon is far more diligent. She gets a late start—she starts putting away money at age 35—but she contributes the same amount ($250 a month) for the entire rest of her working life—to age 65. She contributes for 30 years—three times longer than Frank did!

By the time Frank and Sharon are 65, who do you suppose has more money stockpiled for retirement? The one who saved for only 10 years (Frank), or the one who saved for 30 (Sharon)? The one who put in $30,000 (Frank), or the one who put in $90,000 (Sharon)?

Incredibly, it’s Frank. He saved for only 10 years. But he did it early in his life.

That 10 years’ worth of money, when compounded every year (earning interest, then interest on that interest, then interest on that interest, and so on), winds up creating a nest egg of $353,259. Sharon, who saved for many more years but didn’t start until she was 35, winds up with less money to see her into her golden years—only $306,772.

This concept of compounding is unbelievably powerful—and a great incentive to start your saving young (or to start your youngster’s saving young). —Gregory Close

Performing the dollars-to-hours conversion in your head

As you know from here, we humans aren’t good at comprehending big numbers. We can picture and truly understand “three children,” or “six cans of beer,” or “$45.”

But once numbers get into the hundreds or thousands—forget it. We can intellectually compare two big numbers, but we can’t really picture them.

So when you’re considering buying something, one of the most useful personal psych-outs is to convert its price into the time it would take you to earn it.

Figure out what you make, in dollars per hour. If you make $20 an hour after taxes, and you’re torn about whether or not to buy something priced at $200, you realize that you’d have to work for 10 hours to pay it off.

That sort of calculation makes that $200 price tag far more personal—and gives your brain a chance to truly comprehend its actual cost.

Over 62? How to get 8 percent interest, guaranteed

As you may be painfully aware, the government has been cheerfully taking a chunk out of every paycheck you’ve ever received. You’ve been paying into America’s massive Social Security account, in readiness for the day you retire.

Once you turn 62, you can start withdrawing money from that vast treasure chest.

But here’s the thing: You don’t have to. If you’re healthy and you can afford to hold off on the withdrawals, the government will reward you handsomely: Your benefits go up by 8 percent a year.

Suppose, for example, that you retire at 62, and discover that your Social Security benefit will be $750 a month. You’ll get that for the rest of your life. Congratulations!

But if you don’t start collecting until next year, your monthly check will be $800 for the rest of your life. Wait till you’re 66, and you’ll get $1,000 a month for the rest of your life.

And if you hold out until you’re 70, your monthly check will be a stunning $1,320—almost twice as much every month as you would have received if you’d started collecting at 62.

The increases stop when you’re 70. At that point, withdraw away!

Earnings ballpark: $570 a month, forever

$570 = The extra payment you’ll get each month by waiting until you’re 70 ($1,320 per month vs. $750)

Why you shouldn’t grocery shop after work

Why is it a bad idea to run to the grocery store after work?

Because it’s right before dinner, and you’re hungry.

And science shows, over and over again, that when you’re hungry, you buy more. More than you intended to, more than you need.

You’ll pay more for the food than you would otherwise, too, because your sense of value is thrown off by hunger. And, amazingly enough, you’ll be inclined to buy junkier food—your brain will steer you toward the most caloric items in the store.

For example, Cornell University researchers observed 82 people grocery shopping. The ones who shopped between 1 and 4 p.m. bought lower-calorie, healthier groceries overall than those who shopped between 4 and 7 p.m.

It’s an evolutionary instinct, of course; when you’re hungry, your body’s primary drive is to survive, to ingest calories, at the expense of any other interests.

But now that you know, you can use wisdom to overcome biology.

Stop the tsunami of catalogs

Your life is probably filled with junk mail. Of two kinds, in fact: the electronic kind (spammy email), and the paper kind (in your mailbox).

This flood of advertising is bad for three reasons. First, it takes up time and space in your life. Second, most paper catalogs wind up in the landfill, further junking up the planet. (Only 22 percent of junk mail gets recycled.)

Finally, and most importantly for fans of money, catalogs present temptation. Out of every 100 catalog pages that people flip through, a certain percentage will actually order something. Catalogs work; otherwise merchants wouldn’t keep sending them.

Therefore, the simple act of cutting off your supply of catalogs leads to less spending. Without the option, without the temptation, you won’t be led to buy stuff you don’t actually need.

But how on earth do you turn off the spigot of catalogs?

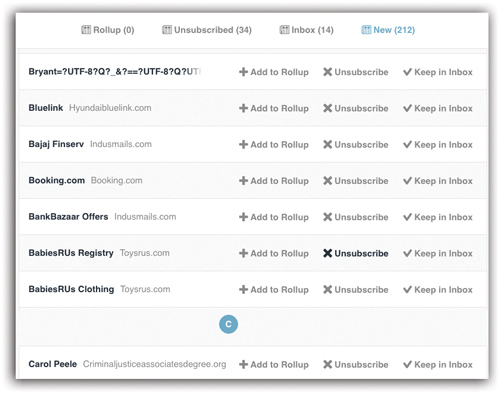

• Email subscriptions. Unroll.me is a free service that shows you a master list of everything you’ve subscribed to—whether you think you did or not. All those newsletters, coupon deals, bank pitches … basically, everything you receive that has a tiny “Unsubscribe” link at the bottom. Unroll.me frees you from all of them en masse, just by offering little Unsubscribe buttons.

To get going, visit Unroll.me (yes, that’s the actual web address). Click Get Started and enter your email address. Unroll.me works with Gmail, Google Apps, Yahoo Mail, AOL Mail, iCloud Mail, or any Microsoft email service (Outlook, Hotmail, MSN, Windows Live).

When you click Unsubscribe, the service begins hiding incoming email from those senders instantly, even if it takes a couple of days for the actual Unsubscribe command to register. Unroll.me doesn’t recognize every junky mailing, but it does an amazing job.

(Whatever marketing messages you don’t unsubscribe from get rolled up into a single daily digest, which is refreshing in its own way.)

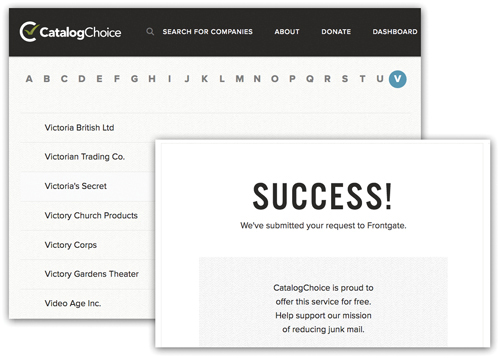

• Mailed catalogs. At CatalogChoice.org, you can rapidly take yourself off of one physical catalog mailing list after another. Alas, it’s not automatic and instantaneous, as with Unroll.me; you’re supposed to search for the name of each company who’s sent you a catalog and unsubscribe from it, one catalog at a time. But it sure beats having to call the 800 number of every catalog sender and give your name and address over and over again.

Savings ballpark: $150 a year

$150 = Two catalog impulse purchases of $75 each

How a shopping list fights back against grocery manipulation

“Never shop when you’re hungry” isn’t the only old saw about grocery shopping. There’s also “Never shop without a list.”

The first reason to work from a shopping list is to make sure you don’t forget something. The second is that a shopping list makes it less likely that you’ll buy stuff you don’t need. (Shoppers who tackle the grocery store without a list spend at least 60 percent more time at the store, pushing the cart aimlessly up and down the aisles; they wind up spending up to twice as much; and what they buy tends to be less healthy.)

Grocery stores know about psychology, too, you know. They’re rigged to get you to buy more, and buy worse. For example:

• The milk is all the way in the back, so you have to pass through aisles of other attractive stuff to get there.

• The healthy stuff (fruits, vegetables, chicken, fish) is always on the outer borders of the store, and the junkier stuff is always in the middle.

• There’s always music playing. It’s called the Milliman Effect, named after researcher Ronald E. Milliman. He discovered, in 1982, that people buy more when there’s slow, peaceful background music playing. (“The higher sales volumes were consistently associated with the slower tempo musical selections—$16,740.23 compared with $12,112.85,” he wrote.)

• The higher-priced options are generally placed on the shelves at eye level, where you spot them first.

In the end, that’s the other huge advantage of list shopping: Sticking to the list neatly defeats all of those grocery stores’ psychological tactics.

The “.99” brain trick

Have you ever wondered why so many prices end in “.99” or “.95”?

Everything costs $4.99 or $9.99 or $89.95—never $5, $10, or $90.

(Let’s not even talk about gas prices, which always end in nine-tenths of a penny. “That’ll be $33.21 and nine-tenths of a cent, sir.”)

The reason for this common practice is screamingly obvious: The stores think that we’re so stupid that we don’t look past the big number. We see $4.99 and we think—“Well, that’s basically four bucks!”

Come on. How insulting is that? Do they really think we’re that easily fooled? We know perfectly well that $4.99 is the same as $5. Actually, with sales tax, we know it’ll come out to be more than five bucks.

You can probably see this punch line coming up Sixth Avenue. The stores don’t price things that way because they think we’re stupid. They do it because we are stupid. We fall for that “.99” trick every time!

In fact, “9” prices increase sales an average of 24 percent over round-number prices. That’s the conclusion of author William Poundstone in his book Priceless: The Myth of Fair Value (and How to Take Advantage of It).

Why does this “psychological pricing” tactic work? Here are some theories:

• The reference-point theory. As you know from page 6, we frequently hunt for a point of reference when we try to gauge value. When we see “$19.95,” our brains jump to the reference point of $20 and say, “Hey! Sure beats $20!”

• The leftmost digit theory. The number before the decimal point is the big number, right? The little penny things after the decimal point don’t matter. We tend to ignore them.

• The “9 = sale” theory. For some reason, prices ending in 9 seem to trigger a “SALE!!!” button in our brains. “9” prices somehow seem like better deals.

In one study, run by researchers from Northwestern University and MIT, sales for a certain dress in a catalog shot up by one-third when they raised its price—from $34 to $39.

(And no, it wasn’t the “perceived value” effect, where people think that something’s more valuable because it has a higher price. When the same dress was priced at $44, there was no difference in demand.)

So how can you avoid falling into the “9” trap? Just by avoiding it. Round up in your head instead of down.

For married couples only: The IYM account

You’ll hear all kinds of advice when you get married. You know: Make time to be together. Don’t go to bed angry. Don’t sweat the small stuff.

Here’s something you may not hear: Don’t combine your bank accounts.

Money, as any married person knows, is the primary kindling for arguments (and divorces).

If you have one joint bank account, it means that the two of you have to agree on every single purchase. Realistically, that will never happen.

So here’s what you do: When you get married, open a new joint bank account—for joint expenses. The two of you fund it in proportion to your income. From this account, you’ll pay your mortgage or rent, utility bills, insurance, kids’ expenses, and so on. There won’t be any conflict, because you both know these are necessary expenses.

Meanwhile, each of you still has your own bank accounts, from which you’re free to spend however you like. If she wants to spend absurd amounts on shoes, she spends on shoes. If he wants to buy a ridiculous two-seater midlife-crisismobile, he goes right ahead.

There won’t be any arguments about money; you can both just shrug and say, “IYM! (It’s your money!)” —Jim Bellomo

The value of giving your money away

You might not expect to get advice on giving to charity in a book designed to give you an aggressive edge in amassing money.

First, of course, there’s an immediate selfish reason to give: a juicy tax deduction. But you also get a huge list of less tangible, more emotional benefits. Many a research study has observed the sense of purpose, inner satisfaction, and spiritual strength that you get by donating to charities. When you give to a cause you believe in, you wind up doing research and expanding your horizons and go to bed knowing you’ve done something to help the world.

But as with any other transaction, there are good and bad deals in charities.

And it’s not as easy to compare them as saying, “Oh, this one has lower overhead,” which is what we used to think. Charity experts argue that it’s impossible to build an effective charity without spending money—to advertise, build awareness, generate interest in the cause, and so on.

But there are thousands of charities. How do you choose?

You might start at CharityNavigator.com. Here you can enter a keyword, like water or cancer, and compare the results. Each charity’s star rating is calculated by a complete dossier of factors, including financial health (expenses, growth, fund-raising efficiency, and so on) and transparency (independence of board members, donor privacy policy, and so on). You can also read exactly what a charity does with its money and read comments from previous donors.

You might also want to visit GiveWell.org (lists only charities that it has already determined to be outstanding), the Better Business Bureau’s Wise Giving Alliance at Give.org (rates charities as Meets Standards, Did Not Disclose, and so on), and GuideStar.org (massive quantities of info on each charity, but not especially easy to use; no ratings).

Buy experiences, not things

What do you get the person who has everything? (Even if it’s you?)

What expenditure will bring the greatest happiness? A new TV? An expensive outfit? A nice car stereo?

According to a rising tide of new studies, the answer is: “Buy experiences, not things.”

The basic idea is that “it’s better to go on a vacation than buy a new couch,” according to the authors of a study published in The Journal of Consumer Psychology. (The paper is called “If Money Doesn’t Make You Happy Then You Probably Aren’t Spending It Right.”)

When it comes to giving or shopping, if your goal is buying happiness, then don’t think of possessions. Think of tickets to a concert, cooking classes, an afternoon at a zip-lining course, or a weekend getaway.

Reason number one: There’s a social component to most of these experiences, and social bonds are well-known factors in happiness levels.

Reason number two: Experiences create memories, which last forever. Mostly, they create good memories, even if the experience didn’t seem that great at the time.

Reason number three: Experiences last longer than the 15-minute period when you’re unboxing a new physical object and trying it out.

Reason number four: Experiences take time to plan—especially trips. And the longer you’re looking forward to something, the more joy you get from it.

This, then, isn’t a tip for spending less money. It’s about spending money better.