Understanding the laws of gravity does not make us free of gravity … it means we can use it to do other things. Until we have informed mankind about the way our brains function, of the way we use them … until we acknowledge that it has been to dominate others, there’s little chance anything will change.

—Henri Laborit (Mon oncle d’Amérique)

Give me a place to put my lever and I will move the world.

—Archimedes

Surely, no one would reasonably dispute that we are the product of how our brains and bodies operate. While this may not be the whole story, it is a reasonable working approximation. However, at the same time it would be hubris to say that all of subjective experience is precisely explained by the anatomy and physiology of the brain, just as it would be absurd to believe that everything we feel and know is understandable by how the brain functions. In the final analysis, for better or for worse, we cannot escape the fact that we are constrained by the brain’s influences and operations on our bodies. To know ourselves is to know our brains, and to know our brains is to know ourselves—more or less.

Following the visionary and experiential work of William James in the early twentieth century, there followed a shift in emphasis on the study of brain function. While James focused on the subjective experience of emotion, the research that followed involved stimulating and excising animal brain tissue and then correlating those sites with observed emotional behaviors (such as rage and fear). First, Walter B. Cannon, the preeminent physiologist of his times (1920s–40s), along with William Bard, underscored the control of emotion in the brain rather than (its experience in) the body.* Their central theory was furthered by James Papez, an obscure physician and neuroanatomist working independently in his small-town office in upstate New York. In his landmark 1937 article titled “A Proposed Mechanism of Emotion,”123 Papez described an “emotional circuit” that was centered upon the upper part of the brain stem, the thalamus. Surrounding the thalamus was a circle, or “limbus,” of nuclei including the hippocampus, hypothalamus and cingulate. The cingulate is an important intermediary, as we shall see, between emotion and reason. Notably, Papez did not include the amygdala (now recognized as an important mediator of emotions, particularly those associated with novelty and threat) in his papers on emotional circuitry.

Papez gave his circuit the catchy title, “the stream of feeling.” Today this region is known as the limbic system, or the emotional brain. The latter descriptive title was coined by the well-known brain researcher Joseph LeDoux. It should be noted that these twentieth-century students of the brain concerned themselves exclusively with the expression of emotion while ignoring subjective emotional experience altogether. Freud’s metaphoric framework and James’s introspective focus on sensations and feelings had been eclipsed by research technology and a fascination with the concrete neural mechanisms and behavioral components of emotional expression. And yet, one might take the liberty here to speculate that Freud (originally a neurologist) would have been delighted, at least, with the locus of emotions. After all, it sat at the core of the brain where he believed that the instincts (or what he dubbed the “id”) resided, well out of range of the “ego” and deliberate consciousness. However, as we shall see, while there may be no direct connection between the instincts (id) and rational consciousness (ego), there are vitally important two-way conduits between the id (instincts) and self-awareness.

Our most primitive instincts reside at the root of the limbic system, in the most ancient, no-frills portion of the brain. There a core of barbed neurons meanders along the brain stem. It is this archaic system that serves the functions of maintaining constancy in the internal milieu and modulating states of arousal. One little nick in this sloppy web of twisted barbed wire, and we find ourselves in an irreversible coma. When it was announced that President Kennedy had been shot and had sustained an injury to his brain stem, my group of research assistant colleagues in James Old’s neurophysiology lab wept as we sat by the television in the University of Michigan student union, realizing that the end had come to our Prince of Camelot.

The neuroanatomist Walle Nauta aptly called the primal brain stem regulation of arousal “the posture of the internal milieu.” With this descriptive connotation, he acknowledged, validated and updated the prophetic work from the previous century of the father of modern physiology, Claude Bernard. Bernard had shown how the primary requirement of all life is the maintenance of a stable internal environment. Whether one is considering a cell, an amoeba, a rock star, a custodian, a king, an astronaut or a president, without this dynamic internal stability in the face of an ever-changing external environment, we would all perish. For example, the oxygen levels and ph (acidity) of the blood must be kept within a very narrow range for life to remain viable. It is the brain stem, through a myriad of complex reflexes, that is “control central” responsible for the minutiae of constant adjustments that are required for the basic maintenance of life. This also includes the regulation of our basic states of arousal, wakefulness and activity. And as messy and primitive as the brain stem reticular activating system is, it does its assigned job of preserving life magnificently.

When compared with the obsessively neat, six-layered columnar organization of the grand cerebral cortex, the brain stem appears a lowly chaotic mess. However, it is just this primitive organization that allows it to carry out its assigned function. It quickly and efficiently gathers diverse sensory data from both inside and outside of the body and keeps the inside relatively stable in the face of a restless and capricious external milieu. At the same time, it collects and summates these various sensory channels to augment the overall state of arousal. This is why the noise of a passing truck can abruptly rouse us from slumber, or why stimulating a comatose patient with music, smells and touch may help return him to the land of the living. Nature has discovered that the modulation of arousal is best served through the nonspecific synesthesia of sights, sounds, smells and tastes in addition to the specific function of the various sensory channels.

Pre-mental consciousness remains as long as we live the powerful root and body of our consciousness. The mind is but the last flower, the cul-de-sac.

—D. H. Lawrence, Psychoanalysis and the Unconscious

The apparent opposition and dominance by the military order of the intricate six-layer cerebral cortex, over the messy anarchistic networks of the “simple- minded” brain stem, was upset by the great Russian-born neuropathologist Paul Ivan Yakovlev. In a seminal 1948 paper, this protégé of Ivan Pavlov challenged the hierarchical (top-down) Cartesian worldview and proposed that just as phylogeny begets ontology, the central nervous system structures, and by implication our increasingly complex behaviors, have evolved from within to outward, from below to above.

The innermost and evolutionarily most primitive brain structures in the brain stem and hypothalamus (the archipallium) are those that regulate the internal states through autonomic control of the viscera and blood vessels. This most primitive system, Yakovlev argued, forms the matrix upon which the remainder of the brain, as well as behavior, is elaborated.

The next level, the limbic system (the paleopallium or paleomammalian brain in terms of evolution and location), is a system related to posture, locomotion and external (i.e., facial) expression of the internal visceral states. This stratum manifests in the form of emotional drives and affects. Finally, the outermost development (the neopallium or neo-cortex), an outgrowth of the middle system in YakovIev’s schema, allows for control, perception, symbolization, language and manipulation of the external environment.

Though we identify primarily with the later, more sophisticated elaboration, Yakovlev emphasized that these brain strata (residing concentrically one within the other—much like Russian nesting dolls) are not functionally independent. Rather, they are overlapping and integrated parts that contribute to the organism’s total behavior. The limbic system and neocortex are rooted in the primitive (visceral) brain stem and are elaborations of its function. It was Yakovlev’s contention that the appearance of the more complex and highly ordered cerebral cortex is an evolutionary refinement—ultimately derived from emotional and visceral functions including ingestion, digestion and elimination. One could say that the brain is a gadget evolved by the stomach to serve its purposes of securing food. Of course one could also argue that the stomach is a device invented by the brain to provide it with the energy and raw materials it needs to function and stay alive. So whose game is it, body or brain? Of course, both arguments are equally true, and this is how organisms function. The brain implies the stomach and the stomach implies the brain; they are mutually intertwined in this democratic web of reciprocity. This organismic view turns on its head the Cartesian, top-down model where the “higher” brain controls the “lower” functions of the body, such as the digestive system. This difference in perspective is not just wordplay; it is rather a wholly different worldview, an entirely different outlook on how the organism works. It is here that Yakovlev has provided a map that modern-day neuroscientists could do well to incorporate into their thinking—that of a deeper appreciation for the organismic welding of a body-brain.

In summary, then, the tendency toward encephalization (according to Yakovlev) is a refinement of the evolutionarily primitive needs of visceral function. Thoughts and feelings are not new and independent processes divorced from visceral activity; we feel and think with our guts. The digestive process, for example, is originally experienced as physical sensations (pure hunger), then as emotional feelings (e.g., hunger as aggression) and finally as cortical refinements in the form of assimilating new perceptions and concepts (as in the hunger for and the digestion of new knowledge). Less flattering to our egocentrism, this (r)evolutionary “bottom-up” perspective focuses on an archaic, homeostatic, survival function as the template of neural organization and consciousness. Our so-called higher thought processes, of which we have become so enamored, are servants rather than masters.

The matrix of function and consciousness, Yakovlev’s sphere of visceration, is in the primitive reticular formation. His methodical analysis of thousands of slices of brain tissue (histology) yielded a poetic vision in the great traditions of his countrymen, Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky. Yakovlev delicately summarized his meticulous, lifelong investigations with the single encompassing statement, “Out of the swamp of the reticular system, the cerebral cortex arose, like a sinful orchid, beautiful and guilty.” Wow … wow … wow!

When I first encountered the ideas of Yakovlev, I registered the truth of his hypothesis viscerally. My gut rumbled in recognition; my emotions soared in excitement. And intellectually, I yearned to digest and savor the exquisite essence of this man’s genius.† I wanted to devour him alive—that is, if he was still alive. It took several days of persistent phone calls to locate him. He was indeed alive and well. This coming-of-age odyssey mutated to locating and meeting with some of my other key intellectual heroes. After finally receiving my doctorate from University of California–Berkeley in 1977, I sent copies of my thesis on stress to several scientists who were my intellectual mentors. This list included Nikolaas Tinbergen, Raymond Dart, Carl Richter, Hans Selye, Ernst Gellhorn, Paul MacLean and Yakovlev himself. I was on my way …

Yakovlev’s lab was in the basement of a dark cavernous building belonging (I believe) to the National Institutes of Health. I proceeded toward the door described to me by the receptionist. It was ever so slightly ajar. As I poked my head in, I was startled by the panoramic vision of shelf after shelf filled with bottles of pickled brains. An impish figure called out, motioning me to his desk. This octogenarian of small stature had a quiet and gentle presence belying his truly expansive character. With twinkling blue eyes and genuine enthusiasm, Yakovlev warmly invited me to sit down. He proceeded to ask me about my interests and was curious why I might have chosen to come so far to visit him.

When I told him about my interest in instincts and about my ideas concerning mind-body healing, stress and self-regulation, he jumped up, grabbed my arm excitedly and took me from jar to jar sharing with me his vast variety of specimens, demonstrating the basic anatomical building blocks of the brain. From there he led me back to his desk and microscope; together we looked at slides of minutely thin slices of brain tissue. He narrated this viewing, waxing lyrical in his elaborate reasoning, as I imagined Darwin might have done in his laboratory a mere hundred or so years earlier. For me, the thrill was so intense that I felt as though I could not contain my pressing urge to jump up and shout, “Yes!” I knew that I was on the right track, that we truly are, to the last of our neurons, just a bunch of animals—and that’s really not so bad.

At one o’clock, after sharing an egg salad sandwich, Yakovlev drew me an intricate map to guide me to my next appointment, which was about forty miles into the Maryland countryside. He did this task in anatomical detail, meticulously employing a set of brightly colored pencils and dissecting, with exacting precision, the best route and its distinguishing landmarks. He offered that if I had time at the end of the day, I was welcome to return by the same route.

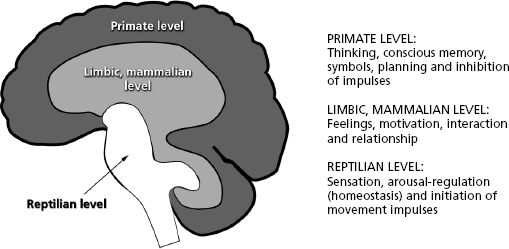

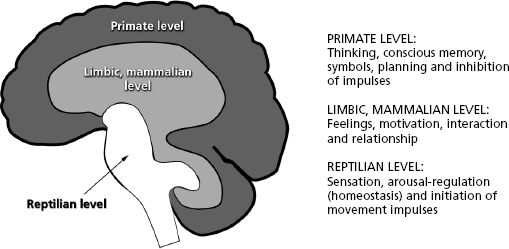

I arrived at my destination right on schedule. Paul MacLean greeted me politely but without the exuberant warmth that had been lavished upon me at my prior appointment. He did, however, ask me the very same question—why I had come so far to see him. I repeated the same answer. MacLean looked at me with a puzzled expression, combining both curiosity and a seemingly paternal concern. “That’s all very interesting, young man,” he offered, “but how do you expect to support yourself?” Feeling somewhat dejected, I asked him many questions about his twenty years of rigorous experimental study of what is now called the triune brain theory. MacLean had associated many specific behaviors suggested by the neuroanatomical pathways laid down by Yakovlev, Nauta and Papez. Although these fundamental brain types show great differences in structure and chemistry, all three intermesh and are meant to function together as a unitary (“triune”) brain. MacLean demonstrated methodically that not only did our neuroanatomy evolve as an elaboration, from the most primitive to the most refined and sophisticated, but (as Darwin would have predicted) so did our behaviors. The implications of this are beyond profound. They tell us that as much as we may not want to admit it, most primitive forms of our ancestral past dwell, latently, deep within us today (see Figure 11.1).124

The Paul MacLean Triune Brain Model

Figure 11.1 This figure illustrates the basic functions of the reptilian (brain stem), paleomammalian (limbic) and primate (neocortex) levels.

The eminent psychiatrist Carl G. Jung presciently recognized the need for the integration of our instinctual layering through the process of psychological individuation. He believed that in the assimilation of what he called the collective unconscious, each person moves toward wholeness. Jung understood that this collective unconscious was not an abstract and symbolic notion, but rather a concrete physical/biological reality:

This whole psychic organism corresponds exactly to the body, which, though individually varied, is in all essential features the specifically human body [and mind] which all men have. In its development and structure, it still preserves elements that connect it with the invertebrates and ultimately with the protozoa. Theoretically, it should be possible to “peel” the collective unconscious, layer by layer, until we came to the psychology of the worm, and even of the amoeba.125

Jung’s mentor, Sigmund Freud, also struggled with the implications of our phylogenetic roots in his seminal work, The Ego and the Id. With disarming honesty and ruthless self-examination, he challenges the basic assumptions of his life’s work. He states that “with the mention of phylogenesis, fresh problems arise, from which one is tempted to draw cautiously back … But there is no help for it,” he bemoans. “The attempt must be made—in spite of the fact that it will lay bare the inadequacy of our whole effort.” Clearly, Freud was questioning the basic validity and premise of his entire psychoanalytic foundation in the light of our phylogenetic heritage. Here he acknowledges the need to incorporate an understanding of our animal roots into the therapeutic process—but how? Yakovlev and MacLean give us just this underpinning.

As did Yakovlev before him, MacLean divided the mammalian brain into three distinctly organized strata, corresponding roughly to the reptilian archipallium, the paleomammalian and the neomammalian epochs of evolutionary development. MacLean developed this map to include the hypothalamus as nodal in the relations between the three brain regions—a driver at the wheel of the brain stem, regulating autonomic nervous system outflow. Drawing on the earlier work of W. R. Hess126 (who shared the 1949 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with the Portuguese neurologist, and ambassador to Spain, Egas Moniz), MacLean and Ernst Gellhorn127 argued that this primitive, pea-sized organ, the hypothalamus, organizes alternative courses of behavior. It directs the behavior of the organism as a whole, a job conventionally ascribed to the neocortex. As we shall see, the control of behavior is shared by various systems throughout the brain—there being no single locus of control. We have not a tripartite brain (containing three separate parts) but a triune brain, as MacLean called it, emphasizing the holistic integration of its parts. With our three brains (actually four if you include the aquatic—homeostatic—component we share with fish), we are presented with the Herculean task of being “of one mind,” a challenge that is both confining and liberating.

The striving and territorial protectiveness of the reptile,

the nurturing and family orientation of the early mammal,

the symbolic and linguistic capacities of

the neo-cortex may multiply our damnation or grace our salvation.

—Jean Houston (The Possible Human)

MacLean’s triune brain has a delicate balancing act to navigate in its triune rather than tripartite role. If you were to face the side of the head and slice the brain in half (providing what is known as the midsagittal view), you would observe a “mind be-lowing” fact. The very front of the brain, the prefrontal cortex, responsible for the most complex functions of human behavior and consciousness, curves all the way around the cranium, making a near U-turn and abutting, with intimate proximity, the most archaic parts of the brain stem, hypothalamus and limbic system. Neuroscience teaches that generally when two parts of the brain are in close anatomical closeness, it is because they are meant to function together. This makes it even more likely that the electrochemical signals will be reliably transmitted.

Descartes might have been utterly flabbergasted at such an intimate relationship between the most primitive and the most refined portions of the brain. Here we have the highest pinnacle of what it is to be human “in bed” (cheek to cheek) with the most primal and archaic vestiges of our animal ancestry. Descartes would have found no rhyme or reason to this physical arrangement. Had he ever speculated in real estate, where value is all about “location, location, location,” he might have been even more perplexed. In addition, as next-door neighbors, brain stem, emotional brain and neocortex must find a common language with which to communicate. Maintaining such an intimate relationship is analogous to the task of interfacing a Craig or IBM supercomputer at MIT with an ancient abacus at the Chinese grocery so that they operate together as one unit. Likewise, the lizard’s rudimentary brain and Einstein’s genius brain (the neocortex) must cohabitate and communicate in a coherent harmony. But what happens when this coexistence between instinct, feeling and reason becomes disrupted?

Phineas Gage, a railroad supervisor in 1848, was the first well-documented case of such a violent divorce. While he was blasting a tunnel near Burlington, Vermont, a three-foot-long spike called a tamping iron was propelled, bullet-like, through his skull. It entered near his eye socket, penetrating his brain, and exited through the crown on the opposite side of his head. To everyone’s amazement, Mr. Gage, minus one eye, “recovered fully.” Well, not quite … While his intellect functioned normally, the injury altered his basic personality. Before the accident, he was well liked by his employers and employees (the ideal middleman). However, the “new” Mr. Gage “was arbitrary, capricious, unstable and considered by those who knew him to be a foul-mouthed boor.” Lacking in motivation, he was unable to hold down a job and ended up drifting, including time spent in a carnival sideshow.‡ One longtime associate observed that “Gage was no longer Gage.” In addition, a Dr. John Harlow, his physician, poignantly, described him in this manner: “Gage has lost the equilibrium or balance between his intellectual faculty and [his] animal propensities.”

Fast-forward one hundred and forty years to Elliot, a patient of the eminent neurologist Antonio Damasio.128 This poor man was at the end of his rope, having burned bridge after bridge in his personal and professional life. Unable to hold a job, bankrupted by various business ventures with disreputable partners and slammed by a rapid succession of divorces, Elliot had sought psychiatric help. His referral to Damasio provided the opportunity for a thorough neurological workup. He passed one cognitive/intellectual test after another and even scored normal on a standard personality inventory. Even on a test purporting to measure moral development, he scored high and was still able to reason through a variety of complex ethical questions. However, something was clearly not “normal” with this man. Yet in his own words Elliot said, “And after all of this I still wouldn’t know what to do.” While being able to “think through” all manner of complex intellectual and moral dilemmas, he was unable to make choices and act accordingly. His moral computers were working, but his moral compass was not.

Eventually, Damasio designed some clever tests that were able to pinpoint Elliot’s deficit and provide clues as to why his life was such a disaster. One of these tests was a type of card game where strategies of risk and gain were played off against one another. When needing to shift his strategy from high risk–high gain (with a probable overall loss) to moderate risk–modest gain (with ultimate gain), Elliott was unable to learn and sustain the transition. Just like the overall outcome in his life, Elliot was an abject failure; he simply could not learn when it mattered. Damasio speculated that his patient was unable to emotionally experience the consequences of his decisions or acts. He could reason perfectly well, except when something of importance was at stake. Essentially, Damasio reasoned that Elliot had lost the ability to feel and to care. He was therefore unable to make (e)valuations, integrate them into meaningful consequences and then act upon them. He was emotionally rudderless.

Damasio puzzled about the possibility that Elliot was a contemporary Phineas Gage. Both physicians, Harlow and Damasio, though separated by more than a century, speculated that their patients had lost their capability to balance instinct and intellect. However, rather than idly pondering this possibility, Damasio and his wife, Hannah, set out on a medically oriented archeological expedition. They located Gage’s preserved skull, ignominiously gathering dust on a shelf in an obscure museum at Harvard Medical School. In a study more like a suspenseful TV crime scene investigation replete with dramatic forensic analysis than a stodgy academic experiment, the Damasios were able to borrow the pierced skull and subject it to sophisticated computer-driven analysis. Using powerful imaging techniques, they were able to predict precisely where the wayward projectile would have ripped through his brain, throwing him to the ground and forever mutilating his personality. With breathtaking anticipation, Gage’s resurrected “virtual brain” revealed devastating destruction of the same tract of nerve cells as were malfunctioning in Elliot’s brain. The mystery was solved! The severing of the brain pathway between the emotional circuits and reason, though extreme in one case and apparently more subtle in the other, was dreadfully injurious to the person’s function and spirit, turning them into wastrels. Their brains were no longer triune but rather tripartite, cut off from the vital communication networks that link up the brains into a coherent whole.

Sandwiched between the frontal lobes and the adjacent limbic regions (the site of both Gage’s violent lobotomy and Elliot’s dysfunctioning neurons) is a folded structure called the cingulate gyrus. This region is pivotal in the integration of thought and feeling.129 Said another way, it is the structure that connects the primitive, rough, raw and instinctual underbelly with the most complex, refined, computational lobes of the neocortex. The cingulate and its associated structures, such as the insula, are what may hold the key to being a fully human animal—in being of one mind, though with three brains.

Both Gage and Elliot lacked a functioning connection between their instinctual and their rational brains. As a consequence of this, they were both lost. Without instinct and reason (warp and weft) woven together on the enchanted loom of the brain, they lacked what it means to be a wholly human being.

The picture of Gage, painted by Harlow, was of a man enslaved by his instinctual whims, “at the same time both animal and childlike.” Then, in 1879, a neurologist named David Ferrier added an experimental perspective to this condition by removing the frontal lobes of monkeys. He discovered that “instead of showing interest and actively exploring their surroundings [as before], curiously prying into all that came within the field of their observation, they remained apathetic, dull, or dozed off to sleep.”130

Unfortunately, Ferrier’s primate research was not headed by the Portuguese neurologist Egas Moniz, who later devised a similar operation on humans, which he called a prefrontal leucotomy. With the advent of this procedure, the scandalous field of “psychosurgery” was birthed. However, these “cures” were usually worse, far worse than the “disease.” And this procedure created multitudes of irreversible zombies. Moniz, as I mentioned earlier, shared the Noble Prize for his horrendous and blatantly pseudo-scientific, freakish work, which “docilized” tens of thousands of patients worldwide. The procedure was most popular in the United States, where Walter Freeman (ironically, the father of one of my graduate advisors, Walter B. Freeman Jr.) invented a procedure called a prefrontal lobotomy. Bizarrely, this treatment, according to the senior Freeman, “was simple enough to be conducted in the offices of any general physician.” Basically, in his own words, his method consisted of “knocking them out with an electric shock” and then (in a “medical procedure” reminiscent of Phineas Gage’s accidental lobotomy by tamping iron) “thrusting an ice pick into the crease of the eyelid and into the frontal lobe of the brain and making the lateral cut by swinging the thing from side to side … an easy procedure, though definitely a disagreeable thing to watch.” (Note Freeman’s curious and callous use of “them” and “thing,” as well as his choice of “surgical instrument”—an ice pick!)

It may seem contradictory that this procedure can produce, as in the case of Phineas Gage, “an individual both animal and childlike”; while Ferrier’s monkeys lacked curiosity and exploration; and, with Damasio’s patient Elliot, the capacity to make valuations and to choose appropriate options was permanently destroyed. Unfortunately, the trend that followed created a Frankensteinian group of tens of thousands of lobotomized patients (and hundreds of thousands more who were zoned out on doctor-prescribed Thorazine and Hadol). Without the animal in the human and without the human in the animal, there is little we can recognize as being a vitally engaged and alive person. It is interesting that many people struggling with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), as well as many violent offenders, appear to exhibit hypo-arousal of their instinctual brains, together with a shutdown in their prefrontal cortex. In this regard the maladaptive behaviors associated with both may be attempts to stimulate themselves in order to feel more human. Unfortunately, the cost of these impulse disorders may be disastrous to both the individual and society.

On the other hand, people who are chronically flooded by emotional eruptions can be just as limited in life. While they are less inhuman (like the Gage-Elliot zombie “body-snatchers”), their explosions can be just as corrosive to the maintenance of intimate and professional relationships, and—it goes without saying—to a coherent sense of self. Traumatized individuals are imprisoned with the proverbial worst of both worlds. At one moment, they are flooded with intrusive emotions like terror, rage and shame, while alternately being shut down, alienating them from feeling-based instinctual grounding, rendering them incapable of a sense of purpose and inept in finding a direction. These may be our clients, relatives, friends or acquaintances who are caught in either extreme, endlessly swinging between emotional convulsion and coma (blandness/shutdown). As such, they are unable to make use of their emotional intelligence. To some degree they represent, when we are under the influence of chronic stress or trauma, the Phineas Gages in all of us.

As above, so below. As below, so above.

—Kybalion

We are more than speaking animals; we are language creatures. However, whether we are confined by the tyranny of language, or liberated by it, is a question that is up for grabs. How we use, or abuse, language has a good deal to do with how we live our lives. Words, in and of themselves, are of little importance to an infant when it is upset. Language needs to be accompanied by close physical soothing in the form of holding, rocking and gentle sounds such as coos and ahs. It is our use of nonverbal tone and cadence that gives language its power to calm and dulcify a baby’s upset. As children develop, they begin both to understand the actual words and to be soothed by the mode in which they are uttered.

However, words must still have a physical context in order for them to be healing and salubrious. You may recall a young boy named Elian Gonzalez, who became the pawn in an outrageous political battle in the state of Florida. Elian’s distant cousins (Cuban exiles living in Miami), supposedly concerned for the boy’s welfare, fought vehemently against Elian’s own father (who was living in Cuba) for custody of this young child. As in Bertolt Brecht’s play The Caucasian Chalk Circle, they were literally pulling this bewildered six-year-old child apart. Eventually, the Supreme Court interceded and blocked Governor Jeb Bush’s efforts to keep Elian in the United States as a “model anti-Castro citizen” and returned him to the custody of his father.

National Guard soldiers were ordered to remove and guard Elian against a hostile, placard-wielding mob as a female federal agent snatched him from the cousins and angry onlookers, holding him securely to her body. Clearly, this unexpected and unwanted embrace from a stranger terrified the already frightened, disoriented and brainwashed child. But then something quite remarkable happened. The agent held him firmly enough to not be ripped away by the angry mob, yet gently enough for her embrace to match the words she calmly recited in Spanish: “Elian, this may seem scary to you right now, but it soon will be better. We’re taking you to see your papa … You will not be taken back to Cuba [which was true for the time being] … You will not be put on a boat again [he had been brought to Miami on a treacherous boat ride]. You are with people who care for you and are going to take care of you.”

These words were carefully scripted, as you might have suspected, by a child psychiatrist who had known of Elian’s history and plight. They were designed to alleviate the boy’s uncertainty and terror. It worked. However, the words alone would not have sufficed without what was obvious in the body language, presence and tone of the female FBI agent. She either instinctively knew (and/or was perhaps coached) how to hold Elian only as tightly as was necessary to protect him but loosely enough so that he wouldn’t feel trapped. With a very gentle rocking, brief eye contact and a gentle calm equipoise, she spoke—with one voice—to Elian’s reptilian, emotional and frontal brain, all at the same time. This unity of voice and holding most likely helped to prevent excessive traumatization and scarring to this child’s delicate and vulnerable psyche. In different ways and in various forms, this is what good trauma therapy does, as we saw in Chapter 8.

Some years ago, I witnessed another example of the instinctive use of human touch with soothing words to ameliorate suffering. I was in the Copenhagen flat of my friend, Inger Agger. Inger had been the chief of psychosocial services for the European Union during the carnage in the former Yugoslavia and was no stranger to trauma and humanitarian catastrophe. So, when the BBC World News, which was on in the background, announced coverage of the East Timor conflagration, we turned to see images of refugees who were clearly dazed and disoriented as they wandered aimlessly into a refugee camp. Posted at the entrance to the camp were a group of rotund Portuguese nuns dressed in white habits.

It was clear to both Inger and me that the alert nuns were instinctively scanning and “triaging” for the refugees, particularly children, who were the most disoriented and in shock. The nun closest to that person would move swiftly, though noninvasively, to that dazed individual and take him into her arms. We watched, with tears streaming down our faces, as the nuns gently held and rocked each one, seemingly whispering something into their ears. And we imagined what they might have been saying—in all likelihood something similar to what the FBI agent had told Elian. However, in stark contrast to what these images were portraying, the BBC commentator pronounced that “these unfortunate souls would be scarred for life,” implying that they would be sentenced to live forever with their traumatic experience. He was missing the point graphically being made by the body language of the nuns and the refugees who were fortunate enough to be enfolded in the goodness of these compassionate women.

This powerful scene illustrates just what it takes to help people thaw, come out of shock and return to life—to set them on their journey of recovering and coping with their misfortune. The work of my nonprofit organization, the Foundation for Human Enrichment, whose volunteers responded in the aftermath of the devastating tsunami in Southeast Asia and Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in the United States, was a more immediate and personal example.131 Here again, it was the weaving of the most immediate and direct physical contact, together with the simplest of words spoken at the right moment, that helped people move out of shock and terror so that they could retain their sense of self, thereby beginning the process of dealing with their terrible losses.

In all of these examples, the brain stem’s reptilian and rhythmic needs, the limbic system’s need for emotional connection, and the neo-cortex’s need to hear consistent calming words converge were all met. We are reassured that whatever we are feeling now, it will pass.

A counterexample was clearly illustrated when the world saw graphic images of dozens of dead and mutilated women’s and children’s bodies carried out of bombed Beirut buildings in the dreadful 2006 Israel-Hezbollah war. Following the televised photos, U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice spoke mechanically in legalese, instead of words of compassion and sorrow, only compounding an already dreadful report. With these visual and auditory images, a metaphorical metal spike is launched, searing through the cingulate gyrus, splitting the (once) triune brain into contradictory shards reminiscent of Phineas Gage. What a pity, when gentle, kindhearted words could have been offered instead, imparting a sense of hope and help unknown already on its way.

The preceding chapters have all skirted around the phenomenon of instinct. However, in this chapter, we have no longer neglected this lodestar, finally giving instinct its due.

* Cannon also mounted a well-reasoned critique of James’s theory by arguing that feedback from the viscera would be too slow and not specific enough to account for different emotions. (These questions will be addressed in Chapter 13.)

† In psychology, appetitive means acquiring.

‡ For an authoritative memoir see M. Macmillan, “Restoring Phineas Gage: A 150th Retrospective,” Journal of the History of the Neurosciences (2000), 9, 42–62.