Chapter 11

Getting Vitamin D from the Sun

In This Chapter

Exposing yourself to sunlight

Exposing yourself to sunlight

Determining how much vitamin D you make

Determining how much vitamin D you make

Figuring out the whens and wheres of getting some sun

Figuring out the whens and wheres of getting some sun

Balancing benefit and risk from sun exposure

Balancing benefit and risk from sun exposure

For about five billion years, the sun has beamed down on the Earth, providing warmth and energy for all life. Fossil records suggest that for about six million of those years, something resembling man (and woman) has walked on the Earth. Just as plants developed photosynthesis to turn the energy of the sun into energy for growth and replication, animals developed the ability to create vitamin D in the skin to provide all the functions described in the second part of this book — and maybe others that we don’t yet know about.

Sunlight is the best source of vitamin D, for many reasons. Consider the most important:

Sunlight is free. You don’t have to buy anything. Your skin makes its own vitamin D, and I’ll tell you how to take advantage of this in this chapter.

Sunlight is free. You don’t have to buy anything. Your skin makes its own vitamin D, and I’ll tell you how to take advantage of this in this chapter.

You can’t overdose on vitamin D made in your skin from sunlight. There’s a limit to how much vitamin D your body can make each day because of mechanisms that kick in to break down vitamin D or limit its production. It doesn’t matter how much time you spend in the sun, you can’t overdose. People who spend all day in the sun, such as construction workers, never get vitamin D toxicity.

You can’t overdose on vitamin D made in your skin from sunlight. There’s a limit to how much vitamin D your body can make each day because of mechanisms that kick in to break down vitamin D or limit its production. It doesn’t matter how much time you spend in the sun, you can’t overdose. People who spend all day in the sun, such as construction workers, never get vitamin D toxicity.

However, today you hear a lot about the dangers of exposing your skin to too much sun. After all, no one wants to develop skin cancer or look older than they really are. So, can you get vitamin D from the sun without risking cancer and wrinkles? I believe you can, and I show you how in this chapter.

Catching Some Rays

The sun is the star of our solar system. All the planets revolve around the sun, but this giant ball of energy is especially important to us because it determines our climate and permits life on Earth. Every second, the sun produces about 386 billion megawatts (million watts) of energy in the form of sunlight. At about 93 million miles from the Earth, it takes about 8 minutes for the light energy of the sun to reach us. The sun deposits about 1,000 watts of energy per square meter of Earth that is directly exposed to sunlight. This is like the energy of ten 100-watt bulbs. A petawatt (PW) is a quadrillion watts. The total energy of sunlight that strikes the Earth’s atmosphere is 174 PW. To give you an idea of how much energy that is, the largest nuclear plant in the world produces 8,200 megawatts.

In the following sections, I explain the different types of ultraviolet rays and give you important information about getting these rays from the sun or from tanning beds.

Checking out ultraviolet rays

The energy of the sun comes to us in the form of visible light, ultraviolet rays, and infrared (heat) rays. The ultraviolet rays concern us because, in addition to creating vitamin D, they can cause sunburn and damage the skin, as well as lead to premature aging, wrinkling, and skin cancer.

Light travels in the form of waves, just like the waves on the ocean. The distance between the tops of two waves is the wavelength. Remember the acronym for the colors of the rainbow? ROY G BIV is for red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet. These colors are all in visible light with red being the longest wavelength color and violet being the shortest. Ultraviolet rays get their name because their wavelength is shorter than the shortest visible light color, violet. We can’t see or feel ultraviolet rays.

Ultraviolet light comes in three types:

Ultraviolet A (UVA) has the longest wavelength of the three types of UV light. Ninety-five percent of the ultraviolet light that reaches the Earth’s surface is UVA. It is present during daylight hours year round. UVA is the wavelength that causes aging of the skin. It can also worsen the skin cancer caused by another form of ultraviolet light, UVB. UVA penetrates deeper into the skin and causes more damage to nuclear material in the cells than UVB. Also, it’s harder to protect yourself from UVA light; whereas both UVA and UVB are blocked by a good sunscreen, UVA is present all year long and passes through windows and some clothes.

Ultraviolet A (UVA) has the longest wavelength of the three types of UV light. Ninety-five percent of the ultraviolet light that reaches the Earth’s surface is UVA. It is present during daylight hours year round. UVA is the wavelength that causes aging of the skin. It can also worsen the skin cancer caused by another form of ultraviolet light, UVB. UVA penetrates deeper into the skin and causes more damage to nuclear material in the cells than UVB. Also, it’s harder to protect yourself from UVA light; whereas both UVA and UVB are blocked by a good sunscreen, UVA is present all year long and passes through windows and some clothes.

Ultraviolet B (UVB) is the middle wavelength of the UV spectrum. It’s thought to be the main cause of skin cancer, but it’s also the wavelength that produces vitamin D (flip to Chapter 1 for details on how your body uses sunlight to create vitamin D). The atmosphere absorbs most of the UVB from the sun, so little gets to the Earth. UVB penetrates only through the outer layer of the skin; it can’t penetrate through glass either, so you can’t get any UVB light indoors even on the brightest day. People with dark skin are less able to make vitamin D because the melanin in their skin blocks UVB just like sunblock. During winter, and in the morning and evening during summer, the angle of the Earth to the sun is such that no UVB reaches the ground. The farther you live from the equator, the less UVB reaches you in the winter.

Ultraviolet B (UVB) is the middle wavelength of the UV spectrum. It’s thought to be the main cause of skin cancer, but it’s also the wavelength that produces vitamin D (flip to Chapter 1 for details on how your body uses sunlight to create vitamin D). The atmosphere absorbs most of the UVB from the sun, so little gets to the Earth. UVB penetrates only through the outer layer of the skin; it can’t penetrate through glass either, so you can’t get any UVB light indoors even on the brightest day. People with dark skin are less able to make vitamin D because the melanin in their skin blocks UVB just like sunblock. During winter, and in the morning and evening during summer, the angle of the Earth to the sun is such that no UVB reaches the ground. The farther you live from the equator, the less UVB reaches you in the winter.

Ultraviolet C (UVC) has the shortest wavelength of the three types of UV light, but the ozone layer that surrounds the Earth absorbs practically all of the UVC, so it has no effect on the skin.

Ultraviolet C (UVC) has the shortest wavelength of the three types of UV light, but the ozone layer that surrounds the Earth absorbs practically all of the UVC, so it has no effect on the skin.

A cautionary word about tanning and tanning salons

Tanning is an American obsession. As a group, Americans are so interested in tanning that about 30 million people use tanning salons every year, (mostly Caucasian females between the ages of 16 and 49). Some argue that it’s not tanning per se that’s bad, but burning. But the more time spent in the sun means more skin damage due to UVA and UVB radiation.

Tanning salons are heavily advertised as a way to “have a healthy color that makes the body seem slimmer.” The picture that accompanies the words is generally of a gorgeously bronzed man and woman. Who wouldn’t want to look like that and/or attract a significant other who looks like that? If only it were so easy!

The ultraviolet rays that tanning salons use are mostly UVA but newer tanning beds also have UVB. As a result, when misused, tanning beds can cause burns. Unfortunately, many people who regularly tan feel that they must go through a damaging burn to set a “good base” for achieving the bronze Adonis look. But this is exactly the kind of damage that leads to skin cancer!

People who frequent tanning salons should protect their eyes or risk developing cataracts (opaque areas in the lens of the eye). Regardless of where you tan, all that sun exposure over years leads to premature aging of the skin and wrinkles.

Seeing How the Skin Responds to the Sun

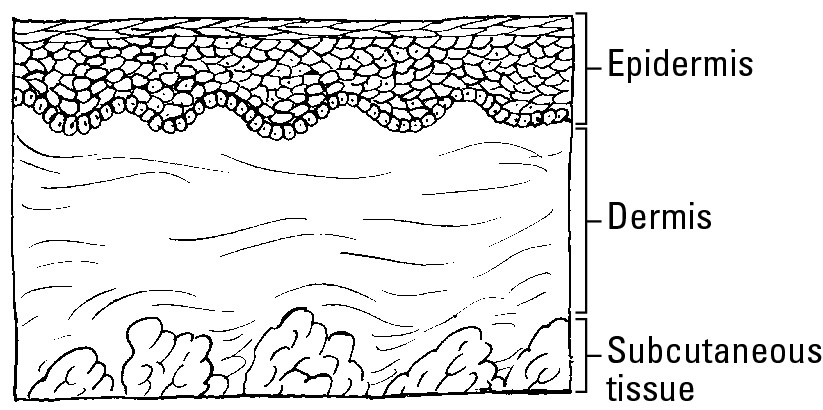

Skin consists of three layers: the epidermis, the dermis, and the subcutaneous tissue (see Figure 11-1).

Figure 11-1: The skin is made up of three layers.

The epidermis is the outer layer and acts as a barrier to the external environment. Cells from the most internal layer of the epidermis — the basal cells — move toward the surface and form a thick outer shell. When they reach the surface, they flake off. If they grow too rapidly and fail to flake off, the skin has a scaly appearance, like psoriasis.

The dermis is the second layer and contains the connective tissue that gives structure to the skin. Within the dermis are these types of connective tissue:

Collagen, for strength

Collagen, for strength

Proteins, for rigidity

Proteins, for rigidity

Elastin, for elasticity

Elastin, for elasticity

The subcutaneous tissue, the third layer, contains the fat cells, providing insulation and filling out the skin.

The sun produces vitamin D in the skin, but it also can cause tanning, burning, premature aging, and skin cancer. This section explains how these changes come about.

How skin wrinkles

As you age, your collagen breaks down and the elastin wears out. The fat cells get smaller. The skin wrinkles and sags. The sweat glands decrease, resulting in dryness. UVA rays, which penetrate the deepest into the skin and can reach to the dermis and beyond, cause more rapid breakdown of collagen and loss of elastin, resulting in premature aging and wrinkles.

How skin tans (and eventually burns)

Tanning is the skin’s attempt to protect itself against too much sunlight. As the skin detects that too much exposure is taking place (scientists don’t know how it actually detects excess exposure), the UV rays cause the release of a brown-colored pigment called melanin from cells in the skin called melanocytes. The melanin combines with oxygen to create the tan color in the skin. Melanin is the same pigment that accounts for the difference in skin color among different racial groups. When melanin is present, it acts as a natural sunscreen and can lengthen the time it takes for skin to burn. (Yes, even deeply black skin eventually burns!)

UVB rays also cause the melanocytes to make more melanin. Something else UVB does is damage the genetic material in our cells called DNA. In extreme cases this will kill skin cells, which appears on the skin surface as burning. But for the cells that live, they may or may not be able to correct the damage to DNA. If you remember from Chapter 6, when certain genes (which are made of DNA) become damaged, cancer can develop. This doesn’t happen immediately, but it does occur over many years.

Knowing How Much Vitamin D You Can Make from the Sun

To know how you can safely use the sun to make vitamin D in your skin, you need to know a few things like your skin type, the time of day, the time of year, and your geographic location in latitude and longitude.

Figuring your minimal erythemal dose

The threshold dose of sun that may produce sunburn is known as the minimal erythemal dose, or MED. If sun exposure continues longer than the MED, a sunburn occurs, with the possibility of long-term damage to your skin.

MED varies from person to person because the amount of pigment you have in your skin plays a part in how quickly your skin burns (see the next section). Your MED also depends on the time of year, the time of day, and the latitude where you live (see the section “The Whens and Wheres of Getting the Right Amount of Sun”).

Assuming you have 25 percent of your skin showing, exposing your skin for slightly less than the length of a MED provides enough time to make about 4,300 IU of vitamin D3. If you were less modest and exposed 90 percent of your skin you could make 17,000 IU of vitamin D3 during the same time period!

You don’t need to cut it that close, though. You can expose your skin for about 20 percent of the time to the MED and still end up with up to 1,000 IU for the day. (To find out how much vitamin D you need to stay healthy, flip to Chapter 2.)

Determining your skin type

The type of skin you have determines how fast you reach a minimal erythemal dose and whether you can produce vitamin D sufficiently.

Dr. Thomas Fitzpatrick at Harvard Medical School created this categorization of skin types in 1975:

Type 1 skin is extremely fair, pale white skin. Eye color is usually blue or hazel, and hair color is often red or blond. These types have numerous freckles; they never tan, but just burn. These people have the highest risk of skin cancer. The group includes true redheads and albinos.

Type 1 skin is extremely fair, pale white skin. Eye color is usually blue or hazel, and hair color is often red or blond. These types have numerous freckles; they never tan, but just burn. These people have the highest risk of skin cancer. The group includes true redheads and albinos.

Type 2 skin is fair, and eye color is blue. These people may tan a little but usually burn. This group includes Northern Europeans and some Scandinavians. Hair color is usually brown although blond hair isn’t uncommon.

Type 2 skin is fair, and eye color is blue. These people may tan a little but usually burn. This group includes Northern Europeans and some Scandinavians. Hair color is usually brown although blond hair isn’t uncommon.

Type 3 skin is a darker shade of white. These people are sensitive to the sun and burn sometimes. They can tan to a light brown. This group includes darker Caucasians. Hair color is brown, as is eye color.

Type 3 skin is a darker shade of white. These people are sensitive to the sun and burn sometimes. They can tan to a light brown. This group includes darker Caucasians. Hair color is brown, as is eye color.

Type 4 skin is a light brown. It doesn’t burn easily, but instead tans to a medium brown. This group is the largest and includes American Indians, Hispanics, Mediterraneans, and Asians. These people have brown or black hair and brown eyes.

Type 4 skin is a light brown. It doesn’t burn easily, but instead tans to a medium brown. This group is the largest and includes American Indians, Hispanics, Mediterraneans, and Asians. These people have brown or black hair and brown eyes.

Type 5 skin usually isn’t sensitive to the sun. This type doesn’t burn easily, but instead tans to a medium or dark brown. This group also contains Hispanics, Middle Easterners, and some African Americans. They have black hair and brown eyes.

Type 5 skin usually isn’t sensitive to the sun. This type doesn’t burn easily, but instead tans to a medium or dark brown. This group also contains Hispanics, Middle Easterners, and some African Americans. They have black hair and brown eyes.

Type 6 skin isn’t sensitive to sun and rarely burns. Pigmentation is very dark. This group includes African Americans and dark-skinned Asians. These people have the lowest risk of skin cancer. Their hair is black and eyes are brown.

Type 6 skin isn’t sensitive to sun and rarely burns. Pigmentation is very dark. This group includes African Americans and dark-skinned Asians. These people have the lowest risk of skin cancer. Their hair is black and eyes are brown.

The Whens and Wheres of Getting the Right Amount of Sun

After all of this talk about the advantages of making vitamin D from the sun, are you ready to grab your towel and head to the nearest pool or beach for a few hours of sun worship? Not so fast. Chances are that you need to spend less than 30 minutes in the sun to give your body enough time to generate the vitamin D you need.

In the following sections, I provide information on calculating the amount of time you need to spend in the sun to get a healthy dose of vitamin D. (That’s really what you want to know, right?) Then I explain the different factors you need to consider when you’re trying to maximize your body’s vitamin D production. These considerations include the time of year, your geographic location, altitude, and the time of day.

Calculating optimal sun-exposure times for making vitamin D

Ola Engelsen, a scientist at the Norwegian Institute for Air Research, has developed an online tool (http://nadir.nilu.no/~olaeng/fastrt/VitD_quartMEDandMED.html) to allow you to calculate how much time you need in the sun to get any dose of vitamin D3.

This calculator lets you enter all the factors that could influence your UVB exposure. These factors include

Latitude

Latitude

Day of the year

Day of the year

Time of day

Time of day

Skin type

Skin type

Ground surface type

Ground surface type

Altitude

Altitude

Using this calculator I calculated the amount of time a person would need to get 1,000 IU of vitamin D from the sun as well as the MED for the six skin types. These calculations are for someone at 39.5 degrees N latitude (Indianapolis, Indiana) on a clear day, wearing shorts and a T-shirt (25 percent skin exposure).

Table 11-1 shows vitamin D and MED values for people with different skin types in Indianapolis, Indiana, at midday on June 22 and December 22.

I recommend that you try this calculator (http://nadir.nilu.no/~olaeng/fastrt/VitD_quartMEDandMED.html) to see how the sun affects you where you live. Just remember that this calculator hasn’t been carefully evaluated to prove that its results are accurate. And like I said before, skin damage from the sun can occur even before you reach the MED.

Enjoying the sun in different seasons

Unless you live near the equator, getting vitamin D from the sun is a moving target. In the summer you need only a little time; in the winter you need a lot, and in fall and spring the time you need increases and decreases, respectively. Why is that? It’s not simply because you wear more clothes in the winter and less in the summer.

In the Northern Hemisphere of the Earth, the sun shines directly down during the summer season of June, July, and August. This is the season when you get the most sun and UV penetration. In the Southern Hemisphere, their summer season is December, January, and February. This direct exposure is why you need so little time in the sun to make vitamin D.

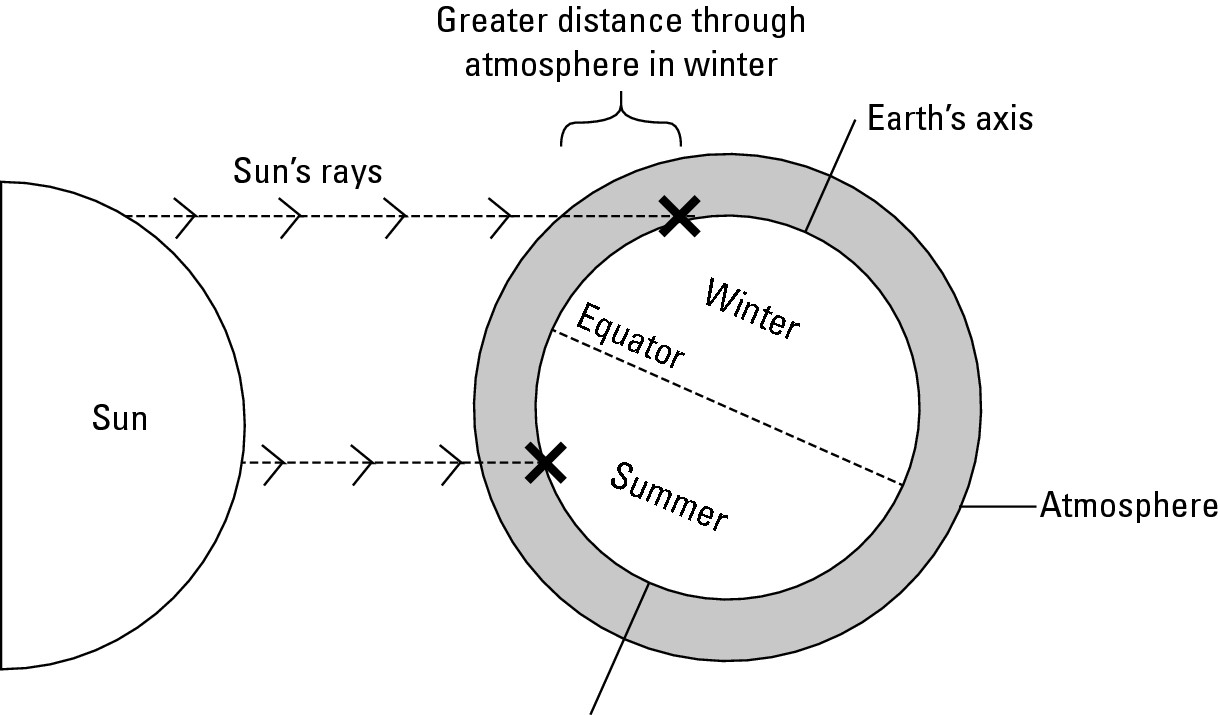

During the winter, the Northern Hemisphere is tilted away from the sun, and the angle that sunlight passes through the atmosphere is more oblique. (See Figure 11-2.) As a result, the sunlight passes through more atmosphere and very little UVB light reaches the ground. You would need to increase the amount of time you spend in the sun to get the same amount of vitamin D. But how many people in Chicago want to spend an hour or more outside in shorts and a T-shirt in December? (Refer to Table 11-1.) Conversely in summer, the Northern Hemisphere is tilted toward the sun, the angle that sunlight passes through is closer to 90 degrees, and so the sunlight has to pass through a shorter distance of approximately the height of the atmosphere.

Figure 11-2: The amount of UVB rays that hit the ground depends on the Earth’s tilt.

Enjoying the sun at different latitudes

The seasonality I just told you about is partly determined by the latitude where you live. The sun shines directly down at the Earth in the tropics, but it comes in at an angle in more temperate latitudes, especially in winter. As a result, the atmosphere absorbs more of the UVB in the winter than when the sun shines directly down in the summer.

For example, type 3 skin in mid-June requires only about 5 minutes of exposure in both Indianapolis (39.5 degrees N latitude) and Acapulco, Mexico (16.5 degrees N latitude), to get 1,000 IU vitamin D (assuming shorts and a T-shirt). In mid-December, it’s another story. Whereas type 3 skin requires 25 minutes of exposure in Indy, in Acapulco the same person would need just 10 minutes (and that 10 minutes would actually be warm and enjoyable!).

Enjoying the sun at different times of day

It’s a no-brainer that the day is hottest at noon or shortly after, and cooler in the morning and evening. Around noon, the rays of the sun come in more directly, and less UVB is lost by absorption as they pass through the atmosphere. However, as the day wears on, the UVB light comes in at a greater angle and the intensity of sun lessens.

To give an example, on a clear day in San Francisco in mid-June, type 3 skin takes 5 minutes at noon to get the 1,000 IU of vitamin D, but type 3 skin needs 15 to 20 minutes at 7 p.m. to get the same amount of vitamin D.

The amount of time needed to get enough sun exposure at different times of day also depends on your latitude and the season. Days shorten as summer ends, so the absolute amount of time available for getting UVB exposure shortens, too. For example, in mid-June there’s still enough sun at 8 p.m. in San Francisco to make some vitamin D, but by mid-August there isn’t enough.

The role that altitude and atmosphere play

There’s one other factor that influences how much UV light reaches your skin — the elevation of where you live. The basic idea here is that the higher your elevation, the closer you are to the sun and the less you’re protected by the atmosphere. If where you lived magically moved from sea level to the top of a mountain 18,000 feet above sea level, you would get 25 percent more UVB. That’s not so much when you’re thinking about a single 1,000 IU dose of vitamin D, but it’s a lot over a lifetime.

The atmosphere isn’t a perfect sphere around the Earth but instead it bulges around the equator, such that the atmosphere is about twice as tall at the equator than it is at the poles. So too, the ambient cloud cover is greater at the equator than it is at the poles. These effects offset the sharp angle of the sun at the equator by reducing the amount of UV that penetrates, whereas at latitudes further from the equator, these effects allow more UV to penetrate to the ground. This is why it isn’t a simple equation to say that there’s less UV penetration the farther you are from the equator. In fact, during summer months the same amount of UV light reaches the ground over 24 hours at the equator as it does at the latitudes and pole that are in summer.

Blocking Out the Sun

We’ve certainly come a long way from the days when our mothers or grandmothers sat with aluminum reflectors concentrating the light on their faces to get a tan. Thanks to repeated exhortations from organizations like the Skin Cancer Foundation, most of us avoid the sun like our ancestors used to avoid the plague.

Obviously, clothing prevents sunlight from reaching your skin, so your skin can’t absorb the UVB rays that cause damage. When used correctly, sunscreen also creates an invisible barrier to UV rays.

Sunscreen was developed during World War II to protect the soldiers in the South Pacific from the burning rays of the sun. Since then, dermatologists have promoted the use of sunscreen to prevent both skin cancer and aging of the skin.

In the following sections, I explain how sunscreen works and tell how to choose and apply it for best results.

Maybe you’re wondering why I’m including information on using sunscreen when I’ve been saying throughout this book that the sun is the best source of vitamin D. When you’re in the sun, you want to expose your skin for the required amount of time to generate vitamin D production, but when that time is up, you want to slather on the sunscreen to protect yourself from all the bad things sun can do like premature aging, wrinkles, and skin cancer.

Seeing how sunscreen protects your skin

The purpose of sunscreen is to block the UVA and UVB rays to prevent sunburn and skin cancer. Benjamin Green was the airman who tried to develop a cream to help the men stationed in the South Pacific in World War II avoid sunburn. After the war, he developed the product further, and it became the basis of Coppertone Suntan Lotion, the first major product of its kind. (Today we call that lotion sunscreen.)

Broad spectrum sunscreens physically block UVA and UVB rays. They can’t pass through to the skin if sufficient sunscreen has been applied. Be careful though because some sunscreens do not block UVA rays.

To compare different sunscreens, Franz Greiter introduced the idea of the Sun Protection Factor (SPF). SPF relates to the amount of UVB radiation required to cause sunburn with the lotion on, compared to the time it takes to get a burn without the lotion. For example, it takes 25 times as much UVB to produce sunburn when a product with an SPF of 25 is on the skin than it does with no lotion at all. That means that if it takes 20 minutes of sun exposure to get a burn without sunscreen, assuming that the strength of the sun doesn’t vary over time, it takes 500 minutes, or more than 8 hours, to get a burn when the lotion is applied correctly. These values are approximate, and of course if you take a swim and much of it washes off, your protected time is significantly reduced.

Choosing and using sunscreen

Make sure the sunscreen you choose is a broad-spectrum sunscreen that protects you against both UVA and UVB. The Skin Cancer Foundation recommends that you should use a sunscreen with at least a 15 SPF.

The American Academy of Dermatology recommends that some combination of the following ingredients be included in a satisfactory sunscreen:

Avobenzone

Avobenzone

Cinoxate

Cinoxate

Ecamsule

Ecamsule

Menthyl anthranilate

Menthyl anthranilate

Octyl methoxycinnamate

Octyl methoxycinnamate

Octyl salicylates

Octyl salicylates

Oxybenzone

Oxybenzone

Sulisobenzone

Sulisobenzone

Titanium dioxide

Titanium dioxide

Zinc oxide

Zinc oxide

Check the label of your product and look for one or more of these ingredients.

The effectiveness of the sunscreen depends on several factors:

The person’s skin type: People with lower-number skin types burn much more quickly than those with higher numbers. A person with type 1 skin takes 16 minutes to burn in mid-June. In theory, with an SPF 25, he has more than 6 hours of protection; however, no sunscreen lasts that long, so this person would need to reapply it several times to get this protection.

The person’s skin type: People with lower-number skin types burn much more quickly than those with higher numbers. A person with type 1 skin takes 16 minutes to burn in mid-June. In theory, with an SPF 25, he has more than 6 hours of protection; however, no sunscreen lasts that long, so this person would need to reapply it several times to get this protection.

The latitude, the season, altitude, and the time of day: Each of these changes the amount of time it takes to burn, greatly changing the amount of time that the sunscreen protects you. Burns will happen faster the closer you are to the equator, in summer, during midday, and the higher above sea level you happen to be.

The latitude, the season, altitude, and the time of day: Each of these changes the amount of time it takes to burn, greatly changing the amount of time that the sunscreen protects you. Burns will happen faster the closer you are to the equator, in summer, during midday, and the higher above sea level you happen to be.

The amount of lotion applied: Sunscreen works only when you put enough on. Unfortunately, the tendency is to apply as little as possible. Obviously, this reduces the effectiveness of the lotion. You can check the label to make sure you use the recommended amount but the Sun Cancer Foundation recommends one ounce for your body (two tablespoons).

The amount of lotion applied: Sunscreen works only when you put enough on. Unfortunately, the tendency is to apply as little as possible. Obviously, this reduces the effectiveness of the lotion. You can check the label to make sure you use the recommended amount but the Sun Cancer Foundation recommends one ounce for your body (two tablespoons).

The activity you’re involved in: If you’re sweating a great deal or swimming, the lotion will come off a lot quicker than if you’re just sitting on the beach. Keep reapplying sunscreen regularly to get the most protection.

The activity you’re involved in: If you’re sweating a great deal or swimming, the lotion will come off a lot quicker than if you’re just sitting on the beach. Keep reapplying sunscreen regularly to get the most protection.

The amount of the sunscreen that the skin absorbs: If the skin absorbs it, the lotion is no longer protective. You want a protective coating on top of your skin.

The amount of the sunscreen that the skin absorbs: If the skin absorbs it, the lotion is no longer protective. You want a protective coating on top of your skin.

Considering the Risks of Sun Exposure

The major negatives for sun exposure that dermatologists emphasize time and time again are premature aging of the skin and the potential for skin cancer, including melanoma. There’s no strong evidence that these abnormalities occur if you limit yourself to a level of sun exposure below the level that causes tanning, and definitely below the level that causes burning.

Premature aging

No proof shows that exposing your skin for a total of 45 minutes a week to the sun increases the risk of premature aging, such as wrinkles of your face in your twenties and thirties. Such a proof would require decades of study and will probably never be attempted. You’re not going to expose your face to the sun, in any case.

This “study” is somewhat unscientific, but ask the next ten people you meet who exhibit premature aging of the face whether they used sunscreen during their life. Most likely, they’ll tell you that they allowed their skin to bake in the sun for hours at a time.

Skin cancer

Skin cancer is the most common of all cancers. It’s also the most easily detected because it arises on the surface of the skin. Despite the large numbers of cases, few people die of skin cancer because it’s detected so early and, with the exception of melanoma, is highly treatable. I mentioned skin cancer briefly earlier in this chapter, but I want to tell you a little more about this disease.

Skin cancer forms in the epidermis, and there are three major types:

Basal cell carcinoma: The mildest form of cancer but also the most common. Eighty percent of skin cancers are basal cell carcinomas. This forms in the basal cells that are the innermost part of the epidermis. UVB light exposure increases the risk of this type of cancer.

Basal cell carcinoma: The mildest form of cancer but also the most common. Eighty percent of skin cancers are basal cell carcinomas. This forms in the basal cells that are the innermost part of the epidermis. UVB light exposure increases the risk of this type of cancer.

Squamous cell carcinoma: This forms in the middle part of the epidermis and is also caused by UVB light. Twenty percent of cancers are squamous cell carcinomas. This form of cancer is more dangerous because it is more likely to spread beyond the skin, a process called metastasis.

Squamous cell carcinoma: This forms in the middle part of the epidermis and is also caused by UVB light. Twenty percent of cancers are squamous cell carcinomas. This form of cancer is more dangerous because it is more likely to spread beyond the skin, a process called metastasis.

Malignant melanoma: This form of skin cancer starts in the melanocytes that produce the pigment melanin. This is the most lethal form of skin cancer, and it accounts for about 5 percent of skin cancers and 75 percent of skin cancer-related deaths. Melanoma isn’t as closely linked to sunburns (which are caused by UVB) as other forms of skin cancer — it may be more sensitive to UVA exposure.

Malignant melanoma: This form of skin cancer starts in the melanocytes that produce the pigment melanin. This is the most lethal form of skin cancer, and it accounts for about 5 percent of skin cancers and 75 percent of skin cancer-related deaths. Melanoma isn’t as closely linked to sunburns (which are caused by UVB) as other forms of skin cancer — it may be more sensitive to UVA exposure.

Skin cancer is found in about two million Americans each year. Because many have more than one cancer on their skin, 3.5 million skin cancers are detected each year. This number is greater than the combined total of annual breast, prostate, lung, and colon cancers. Thankfully most skin cancers aren’t fatal. If you take malignant melanoma cases from the total, fewer than 1,000 deaths a year result from 1,935,000 skin cancer cases.

Non-melanoma skin cancers

Non-melanoma skin cancers are either basal cell carcinoma, named after the type of cell from which it arises, the basal cell in the skin, or squamous cell carcinoma, also named after the type of cell from which it arises. Both usually have no symptoms, such as pain. Basal cell carcinomas have the following characteristics:

They usually appear on the face, where they can cause destruction or disfigurement.

They usually appear on the face, where they can cause destruction or disfigurement.

They occur in people over the age of 50.

They occur in people over the age of 50.

A third of basal cell carcinomas occur on non-sun-exposed areas.

A third of basal cell carcinomas occur on non-sun-exposed areas.

They don’t spread and don’t usually cause death.

They don’t spread and don’t usually cause death.

Treatment with surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation is often successful.

Treatment with surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation is often successful.

Squamous cell carcinomas are much less common than basal cell carcinomas. They have the following characteristics:

They occur in the seventh decade of life.

They occur in the seventh decade of life.

They occur in males more than females.

They occur in males more than females.

They appear on sun-exposed areas, especially the face.

They appear on sun-exposed areas, especially the face.

They do spread, but very rarely, and are just as treatable as basal cell tumors with surgery and sometimes topical medication.

They do spread, but very rarely, and are just as treatable as basal cell tumors with surgery and sometimes topical medication.

Malignant melanoma skin cancer

Malignant melanoma arises from the cells that produce pigment in the skin, the melanocytes. Most of the deaths from skin cancer are the result of malignant melanoma. Malignant melanoma begins as a mole. It’s suspected to be a tumor when it has the following characteristics:

Asymmetry, without a nice round appearance

Asymmetry, without a nice round appearance

Diameter greater than 6 millimeters (but not always)

Diameter greater than 6 millimeters (but not always)

Enlarged size over time

Enlarged size over time

Irregular borders

Irregular borders

Variegated color, instead of one color throughout

Variegated color, instead of one color throughout

Sun exposure is a risk factor for melanoma, but melanoma may occur in areas of the body not exposed to sun too, so other factors are at play. Heredity seems to play a role; you’re more likely to develop a melanoma if other family members have had one. People with a compromised immune system, such as individuals with AIDS, also develop melanoma more often.

Studies indicate that the incidence of melanoma is much more common in people who use tanning salons. Yet people who work outside have melanoma less often than indoor workers. The explanation for these contradictory findings isn’t clear, although people who use tanning salons are exposed to a heavy dose of UVA radiation.

Treatment of malignant melanoma depends on the stage when it’s found. Local melanomas that haven’t spread are removed by surgery and are highly curable. Melanomas that have spread require chemotherapy.

Is There Such a Thing as Safe Sun?

The dermatology community believes that there is no such thing as safe sun. They point out that any exposure to UV rays damages the skin.

I think that’s too conservative for two reasons. The cells of your skin have protective mechanisms that allow it to correct minor damage caused by UV. Also, I believe the argument made by others that using sun for vitamin D is simply a matter of balancing health risks. They point out that high vitamin D status might be involved in the prevention of cancers of the breast, prostate, lung, and colon. Because these are far more deadly than skin cancer, the net benefit of preventing these forms of cancer may outweigh the increased risk of skin cancer that comes with the modest amount of sun you need to make 600 to 800 IU of vitamin D each day in your skin. Let me explain.

About 8,700 deaths will result from malignant melanoma in 2010. How many of the cases originated from sun or tanning salon exposure and how many originated from other sources is impossible to say. Regardless, avoiding the sun won’t eliminate all deaths from malignant melanoma.

In contrast, breast cancer will claim 40,000 lives, prostate cancer 32,000 lives, lung cancer 157,000 lives, and colon and rectal cancer 51,000 lives, for a total of 280,000 deaths in 2010 from cancers. The high-end estimates are that high vitamin D status will reduce the risk of these cancers by 50 percent. If only 20 percent of these cancers can be prevented by a little sun exposure, the benefits of short-term sun exposure (56,000 lives saved) clearly outweigh the risks (8,900 lives lost to melanoma).

These calculations don’t take into account the benefits of improved vitamin D status for your bones and the possibility that vitamin D could help prevent immune diseases, protect your heart, reduce high blood pressure, and prevent diabetes. However, as mentioned in the respective chapters, the nonbone benefits of vitamin D remain unproven at the moment.

Given the uncertainty of the cause of malignant melanoma and the safety of short-term exposure to sunlight, I feel that the positive results from limited sun exposure far outweigh the negatives. Still, this recommendation isn’t meant to give you carte blanche to spend hours of unprotected time in the sun. For most people, the short amount of time needed to get your vitamin D needs met from the sun is worth the risk. You might feel otherwise. Of course, if you’re at high risk for skin cancer because you have type 1 skin or a family history of the disease, or even if you prefer to be more cautious, you should meet your vitamin D needs with diet or supplements (see Chapters 12 and 13).