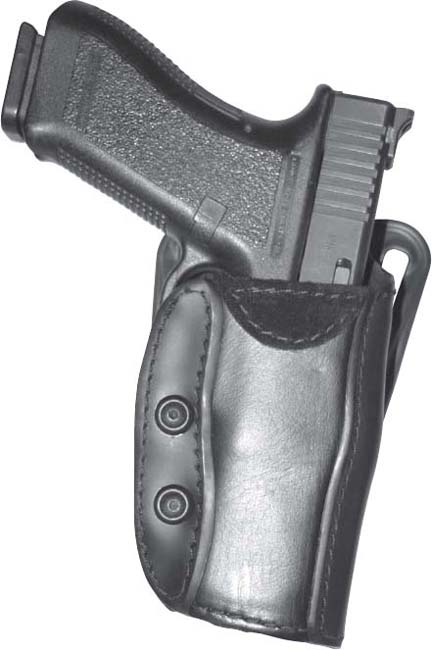

Safariland 567-83 Model hip holster rides low, carries Glock 17 in this example.

The strong-side hip – i.e., the gun hand-side hip – is the odds-on choice for weapon placement for most of those who carry concealed handguns today. It is also the standard location for law enforcement officers in uniform. This is probably not coincidental.

Many ranges, police academies, and shooting schools will allow only strong-side holsters. The theory behind this is that cross draw (including shoulder and fanny pack carries) will cause the gun muzzles to cross other shooters and range officers when weapons are drawn or holstered. Some also worry about the safety of pocket draw and ankle draw. There are action shooting sports – PPC and IDPA, to name two – where anything but a strong-side belt holster is expressly forbidden. Once again, safety is the cited reason.

It is worthwhile to look at other such sports where cross draw holsters are allowed…but are seldom seen. In the early days of IPSC, cross draws actually dominated the winner’s circle for a while. Ray Chapman wore one when he captured the first world championship of the sport. Today, however, even though it’s still allowed, the cross draw has all but disappeared from that sport. A little history is in order. In the mid-1970s, a common IPSC start position was standing with hands clasped at centerline of the torso. With a front cross draw, this allowed the gun hand to be positioned barely above the pistol grip at the moment the start signal went off. IPSC started to go more toward hands-shoulder-high start positions (to give everyone a more level playing field, and to better allow range officers to see if a hand went prematurely to the gun), and the last such match I shot used mostly start positions with hands relaxed at the sides. These positions favored a gun on the same side as the dominant hand. In any case, a strong-side holster brings the gun on target faster because, standing properly, the weapon is already in line with the mark and does not have to be swept across the target.

We saw the same in NRA Action Shooting. Mickey Fowler for many years had a monopoly on the Bianchi Cup, using a front cross draw, specifically an ISI Competition Rig he and his colleague Mike Dalton had designed with Ted Blocker. However, in later years, the Cup has always been won with a straight-draw hip holster.

Quality concealed-carry hip holsters aren’t new. This one, carrying a period S&W Model 39 9mm…

…and was made by the great Chic Gaylord, whose timeless designs are now reproduced by Bell Charter Oak.

Because they begin at the academy with handguns on their dominant hand side, cops tend to stay with the same location for plainclothes wear. Habituation is a powerful thing. Master holster maker and historian John Bianchi invokes Bianchi’s Law: the same gun, in the same place, all the time. It makes the reactive draw second nature.

We saw this in action in the IPSC world in the late Seventies. The second American to become IPSC world champion was the great Ross Seyfried. Ross shot a Pachmayr Custom Colt Government Model 45 from a high-riding Milt Sparks #1AT holster that rode at an FBI tilt behind his right hip. He was a working cattleman in Colorado and a disciple of both Elmer Keith and Jeff Cooper. It was a time when the serious competitors mostly either went cross draw, or wore elaborate speed rigs low on the hip. One who chose the latter was a multimillionaire for whom IPSC was purely sport. Frustrated that Ross had beaten him at the national championships in Denver, this fellow hired a sports physiologist to explain to him how Seyfried had managed to beat him. “I don’t understand it,” the frustrated professional told the wealthy sportsman in essence after viewing tapes of Seyfried. “Your way is faster than his. The way this Seyfried fellow carries his gun is mechanically slower.”

What physiologist and rich guy alike had missed was one simple fact: the multi-millionaire only strapped on his fancy quick-draw holster on match day and at practice sessions. Ross Seyfried wore a #1AT Milt Sparks holster behind his hip every day of his life, though in the saddle on the ranch he carried a 4-inch Smith & Wesson Model 29 44 Magnum. Ross and that holster had developed a symbiotic relationship. Reaching to that spot had become second nature, and made him faster from there than a part-time pistol packer with a more sophisticated, more expensive “speed rig.”

Designed by the late Bruce Nelson, these rough-out Summer Special IWB holsters were produced by Milt Sparks. Left, standard version for Morris Custom Colt 45 automatic. Right, narrow belt loop model to go with corresponding thick but narrow dress belt for suits, also by Sparks, here with Browning Hi-Power.

If the navel is 12 o’clock, a properly worn concealment hip holster puts a right-handed man’s gun at 3:30. In this position, just behind the ileac crest of the pelvis, clothing comes down in a natural drape from the latissimus dorsi to cover the gun without bulge. On a guy of average build, the holstered gun finds itself nestled in a natural hollow below the kidney area. With the jacket opened in the front, the gun is usually invisible from the front. Being just behind the hip, a holstered gun in this location does not seem to get in the way of bucket seats nor most furniture, and doesn’t press into the body when the wearer leans back against a chair surface.

Because of its proximity to the gun hand, and because the gun can come directly up on target from the holster, the strong-side draw is naturally fast. For males, simply bringing the elbow straight back brings the hand almost automatically to the gun.

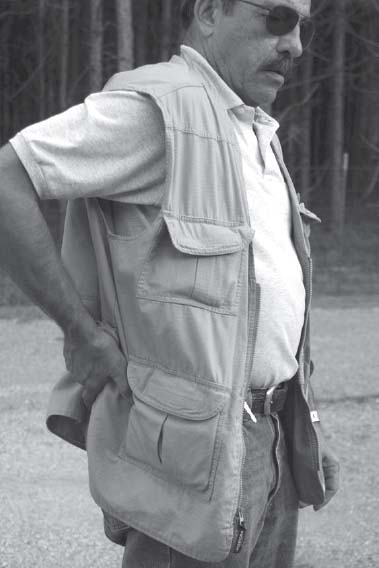

Women’s hips don’t adapt well to male-oriented holsters. Note where Julie Goloski carries her S&W M&P 9mm as she pauses while winning 2006 National Woman IDPA Champion title..

The hip draw does not lend itself to a surreptitious draw – that is, starting with the hand already on the gun, unnoticed – unless the practitioner can get the gun-side third of his body behind some concealing object or structure. Because of the higher, more flaring pelvis and shorter torso, women don’t find this carry nearly as comfortable or as fast as men. As noted elsewhere in this book, cross draw and shoulder carry seem more effective for many women.

Christine Cunningham, an instructor and competitor in the Pacific Northwest, is also a holster-maker. She specializes in “by women, for women” concealed carry gear. Her stuff is tops in quality and function, and very well thought out. You’ll find much good advice, as well as many useful products, at her website, www.womenshooters.com.

The gun behind the hip is positioned so as to be sensitive to exposure and bulge when the wearer bends down or leans forward. This simply means the practitioner has to learn different ways to perform these motions in public.

Exotic leathers have become a status symbol among CCW people. This ParaOrdnance SSP 45 automatic lives in this sharkskin OWB holster/belt combo by Aker.

Continuing with the “clock” concept, let’s look at different spots on the belt for holster placement. 12 o’clock, centerline of the abdomen, will be comfortable only with a small, short-barrel gun. It’s a quick and natural position, particularly for women thanks to their relatively higher belt-lines. My older daughter, tall and slender, prefers to carry her S&W Model 3913 9mm here, in an Alessi Talon inside the waistband holster, or a belly-band. It disappears under an untucked blouse, shirt, or sweater, but provides very fast access.

1 o’clock to 2 o’clock becomes the so-called “appendix position.” An open front garment must be kept fastened to keep it hidden, but a short-barrel gun works great here for access during fighting and grappling. A top trainer who is still active in undercover police work and teaches under the nickname “Southnarc” favors this location, with his retired cop father’s hammer-shrouded Colt Cobra 38 snub-nose inside the waistband at the appendix. It is very fast. Some top IPSC speed demons, such as Jerry “the Burner” Barnhart carry their competition guns in speed rigs at the same location. A small gun conceals well here under untucked closed-front garments. However, the appendix carry causes all but the shortest guns to dig into the juncture of thigh and groin when seated, and the muzzle is pointing at genitals and femoral artery. There are those of us who find this incongruous with our purposes for concealed carry, one of which is to prevent weapons being pointed at such vulnerable parts of our bodies.

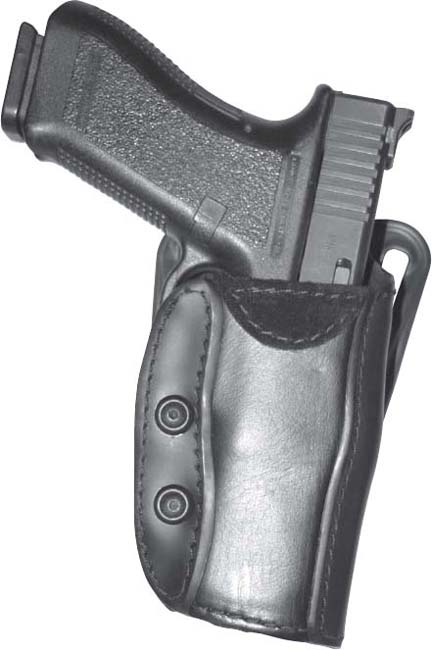

STREET TIP: When you feel the gun butt moving to the rear and “printing,” DON’T adjust it like this. It will be obvious to anyone in line of sight that you’re “carrying.” INSTEAD…

…use your forearm behind your back to push the gun forward, stretch back a little, and you look to the world like someone with a sore back, not someone carrying a gun.

Moving more to the side, the true 3 o’clock position is not ideal for all day concealed wear. Riding on the protuberance of the hip, the gun protrudes accordingly, calling attention to itself even under big, heavy coats. The holstered gun at 3 o’clock will grate mercilessly on the hip-bone. Cops get away with it in uniform because their holsters have orthopedically curved shanks, and the weight is distributed on their wide Sam Browne belts. Neither mitigating factor will be at work in a concealment holster.

3:30, just behind the hip, seems to be optimum for comfort, concealment, and speed. It’s where most professionals end up parking their holsters.

By the time you hit 4 o’clock, there is more likelihood of the butt protruding. When you hit 6 o’clock, the true MOB (middle of back) or SOB (small of back) position, you’re getting into dangerous territory. The SOB is an SOB in more ways than one. While accessible to either hand, it can be mercilessly uncomfortable when you are seated. The rear center hem is the first part of an outer garment that lifts when you bend forward or sit down. The gun butt can catch the hem and completely expose the holstered gun. You can’t see it and usually can’t feel it, meaning you’re the only one in the shopping mall who won’t know that your weapon is exposed.

Another extreme danger of this carry is that any fall that lands you flat on your back will be the equivalent of landing on a rock with your lumbar spine. Very serious injury can result.

Yet another problem with SOB carry is that you can’t exert any significant downward pressure to hold the gun in place when trying to counter a gun snatch attempt. Moreover, biomechanically, you are pretty much putting yourself in an armlock when drawing. As a rule of thumb, any technique that requires you to put yourself in an armlock when defending yourself is a technique you should probably re-evaluate.

Concealment Rig by Ted Blocker makes this full-size Glock 17 concealable for its average-size male owner.

An inside-the-waistband (IWB) holster will conceal the gun better. Simple as that. The drape of the pants from the waist down blends the shape of the holstered gun with that of the body. The hem of the concealing garment has to rise above the belt to reveal the hidden weapon. This carry allows average size guys like me to carry full-size service handguns concealed under nothing more than an opaque, untucked tee or polo shirt, one size large. Held tight to the body by belt pressure, this design minimizes bulge.

Some have tried IWB and found it uncomfortable. This is because their pants were sized for them, and now contain them – plus a holstered gun. For preliminary comfort testing, unbutton the pants at the waist and let out the belt a notch, and try it again. If it’s comfortable now, nature is telling you to let out the pants if possible, or start buying trousers two inches larger in the waist. As noted elsewhere here, this practice “keeps you honest” (i.e., keeps you carrying) because now the pants won’t fit right without the gun in its IWB holster.

Belt clips don’t secure as well as leather loops, for the most part. There are exceptions, such as the appropriately named Alessi Talon, the clips used by Blocker on their DA-2, and the modular Kydex clips on the Mach-2 Honorman holster. Cheaper IWB holsters are notorious for their poor clips.

The IWB holster stays in place largely through belt pressure, so you want a rigid holster mouth to keep the opening from collapsing and interfering with re-holstering. The classic Bianchi #3 Pistol Pocket, a Richard Nichols design, used stiff leather reinforcement for this. Most others followed the lead of the late Bruce Nelson in his famous Summer Special design, and used leather-covered steel inserts to keep the holster mouth open. On rigid Kydex, of course, the material does this by itself.

Inside the waistband, slimness becomes more important, one reason the flat Browning Hi-Power and 1911 pistols are so popular with those who prefer this carry format. The fatter the gun, the more the belt is pushed out from the body. This allows the pants to start sliding down in the holster area, causing frequent need for readjustment.

Because the gun is tight to the body, sometimes against bare skin or sweat-soaked shirts, many makers have built “shielding” into the design to protect the gun from sweat, and bare skin from sharp edges. This works pretty well, but can slow the thumb’s access to a perfect pre-draw grasp, depending on gun design and hand size.

I’ve only designed two holsters in my life. Both were IWB. The first, designed with Ted Blocker, is the LFI Concealment Rig. It’s comprised of a dress gun belt lined with Velcro, and your choice of open top or thumb-break safety strap holster with coordinated Velcro tab. This lets the concealing garment ride all the way to the top edge of your belt without revealing anything, and perhaps more important, lets you adjust the holster almost infinitely for your particular needs: high, low, exact degree of rake (orientation of muzzle) and tilt (orientation of butt) that you want. High versus low is important if, like me, you have to switch between suit pants and uniform pants that tend to ride at the waist, and jeans/cords/BDUs that tend to ride slightly lower at the hips. Now the gun is in exactly the same where-you-want-it spot no matter what you’re wearing. The combination of Velcro shear factor and belt tension holds it in place. It’s very secure, and I’ve taught weapon retention classes with one without it coming loose. Matching magazine pouches are available, and the LFI Concealment Rig also works as a cross draw.

The other was designed for Mitch Rosen, at his request. He wanted an open-top rig that would carry a heavy, full-size fighting handgun without the weight of the loaded magazine in its butt tilting it backward to “print,” or expose itself through clothing. I designed an FBI-tilt IWB scabbard with a single strong belt loop at the rear, behind the gun, where the loop’s bulk wouldn’t add to the holster’s. In this position, the holster “levered” the gun forward and prevented it from tilting backwards. I called it the Rear Guard, because the loop at the rear guarded against rearward holster shifting. Mitch was kind enough to call it the Ayoob Rear Guard. It was shortened to ARG, which I’ve always pronounced as Ay-Arr-Gee. Unfortunately, folks started pronouncing the acronym in one syllable, which sounded like “Arrgghh.” I suppose I should just be glad I didn’t name it Super Holster Inside Trousers. After 9/11/01, Mitch changed the name to American Rear Guard. Still the same excellent holster, though.

The belly-band is a variation of inside-the-waistband carry, approximately four inches of elastic strapping with a gun pouch. It is worn best at belt level, “over the underwear and under the over-wear.” The first of these I ever saw was a John Bianchi prototype in Gun World magazine, circa 1960. Bianchi didn’t bring it out back then, but in a few years, a firm in Brooklyn named MMGR did. I wore an MMGR belly-band to my grad school tests one hot summer day when I was 21, and noticed the day I got home that the beautiful blue finish of my S&W Model 36 Chief Special had turned brown on the side next to my body. Some later belly-band designs, such as the Gould & Goodrich, used a separate plastic shield on the gun pouch to protect the weapon from this, but expect some degree of sweat exposure with this type of carry. The Tenifer finish of the Glock pistols seems to stand up to this best, followed by the similar Mellonite finish used on S&W M&P autos, followed by industrial hard chrome finishes and stainless. The Glocks will discolor after long carry in this fashion, but won’t actually rust.

While I prefer the belly-band in the front cross draw position for a 2-inch 38, larger guns work best behind the hip. They’re a great alternative under a tucked-in shirt for those who work in business suit environments and must take the suit coat off in the office, but can’t afford for the gun to become visible. A “Hackathorn rip” movement is the best drawing option here. I also know medical professionals in gun-free zones in high crime areas, who wear small handguns this way under their scrubs.

There are many good belly-bands. My personal favorite has always been the unfortunately discontinued Bianchi Ranger, with built-in money belt. It has been my companion all over the world. I’ve carried S&W 4-inch 44 Magnums in it, perfectly concealed on the streets in cities from South Africa to Europe.

Since they offer little protection against sharp edges, belly-bands work best with edge-free guns. That said, properly adjusted they can be incredibly comfortable. One downside to them, though, is that you practically need a shoe-horn to get the gun back in. The near-impossibility of quickly reholstering means that regular range practice is out of the question, and you have to have an action plan that includes putting the gun away in pocket or waistband after making a belly-band draw on the street.

The “tuckable” is a different breed, the latest development in this area and one of the most widely copied. It goes back to Dave Workman, a holster-maker who is also a leading Second Amendment advocate and gun author. For those with office dress codes, Dave came up with an inside the waistband holster that had a separate paddle that secured on the belt, creating a deep “V” between the holster and that securing portion, into which a dress shirt could be tucked. Worn at 3:30, or in the appendix position, or at 11 o’clock in a front cross draw, it hid the gun perfectly. The snap-on belt loop could be disguised as a key holder simply by putting a small key ring in the loop. When he looked for a larger manufacturer to handle the design, I steered Dave to Mitch Rosen, who introduced it to the world as The Workman. It instantly became the most copied new rig in the holster field. This style also functions perfectly well as an ordinary inside the waistband holster.

Another IWB variation that goes deep inside the waistband is the Pager Pal. A flat semi-disk of leather contains a small revolver or auto that rides inside the pants and below the belt, hooked onto the belt by a camouflaged pager, cell phone carrier, knife pouch, etc. When carried cross draw, the support hand grabs the pager or whatever and pulls upward, exposing the holster for the gun hand’s draw. I found that if you don’t have a large butt, you can carry it on your strong side behind the hip and knife the hand down inside the pants to get at the gun. Not my first choice, but an interesting option that some have found useful.

The Yaqui Slide is extremely popular for concealed carry. Here, the Galco version carries a custom .40 cal. Glock 23 with Caspian slide, BoMar sights, and Hybrid-Port recoil reduction system.

Outside-the-waistband (OWB) is more comfortable, but requires more effort for concealment. The most concealable designs copy to some degree the Pancake holsters of Roy Baker. Rounded, thus their eponymous shape, Baker’s holsters and some of today’s copies have three belt slots, one in the rear and two in the front. This allows the shooter to set up for forward “FBI” tilt, straight up hip-draw, or straight up cross draw. With the belt tensioning the holster fore and aft of the actual scabbard body, the gun is pulled in tighter to the hip for better concealment.

The Yaqui Slide holster, a “skeleton” design popularized by Milt Sparks, is handy in that it fits a number of different barrel length guns with the same frame. Points to note with it, though: 1) If sitting in an armchair and the arm of the chair bumps the gun muzzle, the whole gun can be pushed up and out of the holster. 2) Carbon and dirt on the gun after firing can, while it’s holstered, transfer to the underlying trousers. 3) Sharp-edged sights, or deep Picatinny-style rails on the dust cover (lower front of frame) of some modern military style auto pistols, can snag on the bottom edge of the Yaqui Slide, dangerously stalling the draw. 4) Back in the ’70s, a selling point of this design was that it could stay on the belt with the gun removed, and would often go unrecognized as a holster. This is probably not the case today. The Don Hume version is certainly a best buy for quality vis-à-vis price today, and a key objectionable point to this particular style is removed with models that have thumb-break safety snaps, as offered by Bianchi, Ted Blocker, and others.

With any strong-side hip holster, a 4-inch barrel revolver or 5-inch barrel auto pistol are about the max in overall length that will carry comfortably before the muzzle hits the chair or seat when you sit down, causing some awkwardness and discomfort factor. Larger men, with larger butts and higher beltlines, can perhaps get away with longer handguns.

An outside-the-belt holster is particularly vulnerable to the gun leaning outward because of the butt portion’s weight. Each generation of pistol packers seems to discover that a 3-inch or particularly 4-inch revolver, or a similar size auto, may actually conceal better because the longer barrel bears lightly against hip or leg, pushing the butt in toward the torso to better maintain concealment.

For some, at least in some circumstances, the most viable option is a gun carried ITB, or in the belt, that is, between the belt and the trousers. This allows the user to wear trousers that fit him normally, but the belt pressure pulls the gun in tight as on IWB. However, the IWB advantages of allowing the bottom of the garment to rise higher without revealing the gun, and of breaking up the outline of the holstered gun, are lost. Mitch Rosen’s appropriately titled “Middleman” is one holster designed expressly for this purpose. Another that is perfectly adaptable to this is the Quad Concealment from Elmer MacEvoy’s company Leather Arsenal. Its name comes from the fact that this ingenious and extremely useful rig can be worn outside the belt or between belt and trousers, and can be worn either way ambidextrously.

Author explains why he doesn’t like paddle holsters, but why they can work for some people in some situations. This is one of the best of the breed, by Aker, carrying Ruger GP100 357 Magnum.

Some belt holsters are made with a paddle that goes inside the waistband, securing on the belt and holding the holstered gun outside the pants. The one strong point of this design is convenience: easy on, relatively easy off. I don’t care for them for the following reasons. 1) I’ve seen too many fail to secure, resulting in the holster coming out with the gun. It’s funny at a match or a class, but on the street, it would get you killed. The only thing that would save you would be if your opponent was laughing at you too hard to shoot straight. 2) Since the belt is securing on the paddle rather than the holster itself, guns carried in this fashion tend to lean out away from the body, compromising concealment. 3) The juncture of paddle and holster body is, by nature, weak. I’ve seen even the best brands break here, yielding the holstered gun to the “attacker,” in weapon retention drills. 4) The convenient on/off nature of this holster fosters an “I’ll wear it when I need it” mentality, causing the gun to be left behind and to not be present when, unpredictably, it is needed.

There are many companies that make high quality paddle holsters, but none can get past these inherent weaknesses in the paddle concept. Go to the same maker, turn the page of their catalog, and order one of their holsters that properly secures to a good dress gun belt.

Replaceable belt-clip modules of Kydex IWB holster by Mach 2, the Honorman, “flex” and help conceal this Glock 27 without shifting. Note also “body shield” to keep sweat away from gun, and sharp gun edges away from underlying skin and clothing.

Leather or synthetic? Leather is the classic, and so long as it gets an occasional application of neatsfoot oil or other leather treatment, won’t “squeak.” Cowhide is by far the most common. Horsehide has its fans: it is thinner and proportionally more rigid, but seems to scratch more easily. Sharkskin is expensive, but extremely handsome and very long-lasting and scuff-resistant. It may last you longer than it did the shark. (I often wear sharkskin belts in court. Doesn’t ward the lawyers off or anything, but seems appropriate, especially during some cross-examinations.) Elephant hide? Hellaciously expensive, but certainly tough, and predictably thicker than you probably need. Alligator and snakeskin holsters seem better suited to “show” than “go.” For the most part, cowhide and horsehide are where it’s at.

Rough-out or grain-out? The latter rules with outside-the-waistband carry. The only guy who ever seemed to like rough-side-out belt scabbards was John Wayne, who wore a personally-owned rig of that kind in many of his cowboy movies. It tends to hold sand and dust. The guy who popularized rough-out holster design in concealed carry was the late, great Bruce Nelson, whose Summer Special design was hugely popularized by another departed giant of the industry, Milt Sparks. They found that inside-the-waistband, the rough outer surface had enough friction with clothing to help keep the holster from shifting position; early versions had only one belt attachment loop, and were less stable than the later, improved two-loop Summer Special variations. As a bonus, the smooth grain of the leather was now toward the gun, less likely to trap sand and dust and cause wear on the finish. Some theorized that this also made the draw smoother. However, sweat tended to rapidly migrate through these holsters to the gun, much more so than grain-out IWB holsters that seem to repel perspiration better.

Plastics, particularly Kydex, do not loosen with age like leather, nor do they tend to start out too tight and need a break-in, again a common thing with good leather. Kydex certainly provides more sweat protection to the gun. However, I’m not persuaded that they’re longer lasting. The reason is that their belt attachments are more likely to break. In retention training, with constant struggles for the neutralized guns between two men moving full power, I’ve seen a lot more Kydex and generic plastic holsters break than leather ones. The most secure of the Kydex holsters are the inside-the-belt variations. A genuine tactical problem with Kydex is that it makes a distinctive noise when the gun is drawn or holstered. Sometimes, the concealed handgun carrier wants a surreptitious draw, in which the weapon is slipped out of the holster unnoticed. This is much more difficult with Kydex and requires aching slowness. Score a point for traditional leather in that situation.

However, one advantage of Kydex holsters is that the better ones come with spacers in their belt loops to allow the wearer to adjust the holster to properly fit belts of different widths. For the person switching between casual pants and dress pants, the latter generally mandating narrow belts due to fashion pressure or belt loop size, this can be an advantage. The better Kydex holsters today, such as the Blade-Tech, can ride sufficiently tight to the body for good concealment. They also lend themselves better than leather to carrying a pistol already mounted with flashlight, with reasonable concealment.

There are very few fabric holsters, i.e., ballistic nylon, which will stand up. Most make it difficult to re-holster. For the most part, the “cloth” holsters are at their best as cheap “belt-mounted gun bags” that hold the gun for plinking sessions at the range, and not for daily carry in what might become a dangerous tactical environment.

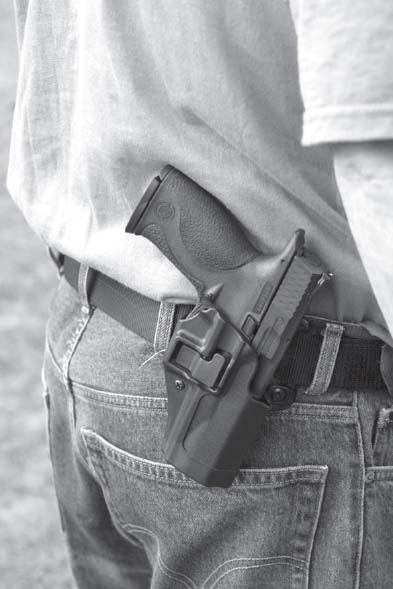

Blackhawk SERPA is a snatch-resistant, concealable rig that effectively hides this S&W M&P 9mm under a coat. It has been adjusted to desirable forward tilt angle. Finger paddle is easily released by owner’s safely extended trigger finger when draw begins.

“Snatch-resistant” concealment holsters are discussed in the Open Carry chapter. However, they should not be neglected in concealed carry. People who haven’t learned to properly activate retention devices call them “suicide straps,” and prefer open top. They will tell you, “It’s concealed, so you don’t have to worry about someone grabbing it.” Rubbish! Your attacker may know from previous contact with you that you carry a pistol, and even where you carry it. He may have spotted it when scoping you out. Or you might get into a fight and the other guy wraps his arms around your waist for a bear hug or throw and feels the gun, at which time the fight for the pistol is on.

It is good to have at least one “level of security,” that is, one additional thing the suspect has to do to shoot you with your gun in addition to the obvious movement of pulling it out of the holster. An on-safe pistol should count as one level of security. So should a thumb-break safety device. A hidden or “secret” release device may count as two levels. A holster requiring a push in an unusual direction to draw is another level. It’s not a bad idea for the holster to have at least one “level of security.”

A safety strap can also keep the gun in the holster when something other than a hand pulls at it. The gun butt can catch in brush when sliding down a hillside, or on a counter you’re pushed against in a physical fight, or simply come out if you take a tumble butt-over-teakettle. There have been cases of guns falling out of holsters on amusement park rides that put the rushing riders upside-down.

Some, like me, justify the occasional wear of open-top holsters with their extensive experience in handgun retention training. However, even we are likely to have at least a safety strap when out in the brush or performing other strenuous physical activity, or when “open carrying” as police investigators at the station or other environments that increase the likelihood of a gun-snatch attempt.

With practice and proper technique, the difference between open-top and thumb-break in drawing speed is a very thin fraction of a second, a fair price to pay for the added security.

Ayoob designed the LFI Concealment Rig with Ted Blocker, whose namesake company now in other hands still finds it a good seller. Velcro tab on holster (and spare mag carrier, shown) mates with Velcro lining inside the dress gunbelt to secure solidly, and allow wide options to wearer as to height, angle, and location. Pistol is SIG P220 ST 45, with Hogue stocks.

Holsters and belts are as symbiotic as automobiles and tires. We firearms trainers can tell you ad nauseum of students who come in with expensive guns in holsters that should have a Fruit of the Loom label, or may be proof incarnate that you can skin a chicken and tan its hide and make a holster out of it. However, we can also tell you about the students who come in with fine guns in top quality holsters that are hanging off crappy, floppy, narrow little belts whose institutional memory is probably the words, “Attention K-Mart shoppers!”

Even the best holster will, on a poor belt, hang outward from the body. It will shift its position constantly, violating the twin needs of discretion and comfort. There may be so much slop between the belt and the holster’s belt loops, and so much undesirable flexibility in the belt itself, that you can exert the drawing movement for an inch or more and the gun has not begun to leave the holster.

The belt should be fairly stiff, and should be fitted tightly to the holster loops. Often, the easiest way to achieve this is to use a “mated” gun and dress gun belt from the same maker. This also gives a certain pride of ownership. Looks great at an open carry barbecue. Of course, we carry them concealed for the most part, so it’s not really a fashion statement, just a matter of personal satisfaction. I personally don’t care who made the belt and the holster, I care that they go together.

You wouldn’t save up to buy a Volvo or a Mercedes to keep your family safe, and then put on two-ply retread tires. Counterproductive. Ditto a good gun in a crappy holster, or a good gun in a good holster on a crappy belt. I would rather have a $300 police trade-in handgun in a good holster on a good belt, than a $3000 custom pistol in an inappropriate holster on an inappropriate belt. The man with the latter combination will inevitably lose a quick-draw contest to the equally skilled man armed with the former.

For those who don’t care for leather, top-quality nylon dress gun belts such as the defining Wilderness Instructor’s Belt will work fine with casual clothing, and companies like Blackhawk make narrow faux leather belts with matching-loop holsters that will work well in concealment. “Armed and green,” as it were.

A larger gun in a well-selected holster will carry more comfortably and in more discreet concealment than a smaller gun in a poorly-selected holster on an inappropriate belt. Gun, holster, and belt are all part of a system, and if any of those links fail, the whole chain will fail. We’re talking about life-saving emergency rescue equipment here. Failure is unacceptable.

Spent casings are inches apart from ex-SWAT cop Steve Denney’s new SIG P250 9mm as he tests it with a fast double tap.

I’ve been carrying concealed firearms since 1968, which was my first year as a sworn law enforcement officer. I was finishing the last year of my Criminology Degree at Florida State University and joined the Tallahassee Police Department as a Reserve Officer. Since then, I’ve learned a few lessons about concealed carry by trial and error, but my knowledge about firearms has been improved immensely by reading what the experts were saying. In the early 1970s, besides reading articles by people with names like Cooper, Gaylord, Askins, Skelton, etc., I started reading articles from a guy by the name of Massad Ayoob. I began to wonder, who was this Ayoob guy and, more importantly, why did what he wrote actually make sense, based on my own experience? My relationship with Mas’ writing was strictly one-sided (he wrote and I read) from then until 1999, when I finally had the chance to take my first LFI course. Since then we have become good friends and I have become an instructor with him for his Lethal Force Institute. That has given me a precious opportunity to see how he acquires and uses the knowledge that he shares with others in his training classes, his writing and his case work as an expert witness. So when he said he was writing a book about concealed carry, I thought: “This has got to be good!”

Well, it is. I have been poring over the manuscript for the past week and I am happy to report that Mas has put together a winner. And a timely winner, at that. Concealed carry has been a hot topic in the world of gun ownership for the past two decades or so. More and more opportunities for decent, law abiding citizens to protect themselves by legally carrying concealed firearms have emerged as State after State has adopted more realistic concealed carry laws. Even so, only about two percent of the people eligible for a concealed carry permit actually apply for one. That is starting to change, however. Of course, September 11, 2001 started folks thinking more seriously about the subject. And most recently, the mass murder of students at Virginia Tech, the shootings in malls in Omaha and Salt Lake City and the armed attacks on religious centers in Arvada and Colorado Springs are causing people to reassess their vulnerability as they go about their daily lives. As more and more people come to the conclusion that they need to take realistic precautions against violent attack, the need for sensible concealed carry advice will continue to expand.

One of the things that has always impressed me about the way Mas works is that he is not just a teacher and not just a writer. He is a true student of firearms, their history and their use. This book reflects his serious research of the subject, as well as his ability to communicate with his audience. The references to many of the legendary names in the firearms world and many of the real-world case studies are not just academic. Mas has known most of the greats. And anyone who knows Mas also knows that he is always asking questions, always analyzing other people’s views and always seeking more and more knowledge. It’s not just the “names” either. I have been with him when he asked the ordinary man or woman what their impressions were on a particular gun or piece of gear. “How do you like that Beretta,” he asked a young highway patrolman we were sharing a gas pump with during a fuel stop on a trip across the Great Plains. “How’s that holster workin’ for ya,” to a Sheriff’s Deputy we met at a convenience store. “What do you think they should do to improve that” is a common question we hear when he calls on us to help evaluate some gun or other gear that has been sent to him to “T & E.” Beyond the equipment, Mas gathers real-life information about the use of firearms for self defense. Certainly his case work as an expert has given him unique access to incidents from the streets. Some of them are high profile, some rather ordinary. Except to the people involved. Every case has its lessons. And, very often, his students have their stories. Stories that can make the hair on the back of your neck stand up, or bring a tear to your eye. Like the female student who had been the victim of two violent sexual assaults. The first time her attacker succeeded in raping her. The second attacker did not. The difference? The second time she was armed and prepared to defend herself. Or the Roman Catholic priest, who grew up in a foreign country known for its civil strife. He has been shot five times and stabbed once, all in separate incidents. He now lives in the United States, carries every day, and when he quietly relates his story, he simply says: “Never again.”

These are the sort of people Mas spends time with as both a teacher and as a student of the human experience. And that experience is what he willingly and skillfully shares with his students and his readers. In this book, he has compiled decades of experience in not just the carrying of firearms, but the shooting of firearms. Mas has been a competitive shooter since the old PPC days. He was a “regular” at the Bianchi Cup and other national matches. He still competes regularly in law enforcement competitions and International Defensive Pistol Association (IDPA) matches. In fact, Mas was one of the first IDPA Four Gun Masters and became the first Five Gun Master, when an additional revolver category was established by IDPA a couple of years ago. He is also an avid researcher of the history of carrying firearms and their use by police and ordinary private citizens alike. As such, he was a guest lecturer at a conference of writers and historians in Tombstone, Arizona, assembled to discuss probably the most famous gunfight ever, the shootout at the OK Corral. And, on a more contemporary note, he was requested to represent the “expert witness” point of view on a panel of American Bar Association legal experts who were making a Continuing Legal Education training tape for attorneys. The tape specifically addresses the investigation, prosecution and effective defense of people who have had to use deadly force to protect themselves or others.

In this book, Mas discusses both WHY we carry and HOW to carry. Mas explains the concepts behind the two styles of holsters he has designed, the LFI Rig and the Ayoob Rear Guard, and why holster selection is such an important part of your carry “system.” He also explains the need to practice drawing from concealment, in order to quickly respond to any threat. He explains the rationale behind two drawing methods that he developed: using the StressFire “Cover Crouch” to draw from an ankle rig and the Fingertip Sweep (he calls it “reach out and touch yourself”) used to positively clear an open front garment for a smooth same-side draw. Mas began developing his “StressFire” shooting techniques back in the 1970’s. By late 1981, at the suggestion of world champion shooter Ray Chapman, he established the Lethal Force Institute and has been instructing “certified card carrying good guys” there ever since. The Chief of Police of the department where Mas serves as a Captain, Russell Lary, has entrusted his son to Mas’ tutelage to the extent that he has attended all of the LFI classes, LFI-I, II & III, and he just recently completed the most advanced class, LFI-IV. Yes, Mas really is a Captain in the Grantham, NH Police Department. I know the Chief, and he is delighted to have such a true “human resource” available to the residents of his community.

A lot has changed in the nearly 40 years since I started in this field. A lot happened before that, of course, but I see the next major steps coming in the immediate future. People are tired of being victimized by people who use guns and other weapons illegally. And people are tired of being victimized by anti-gun advocates and the laws and rules for which they are responsible. They have been shown to be worse than ineffective. They have put decent people unnecessarily at risk in “Gun-Free Zones,” that are only gun-free to the law abiding. They continue to attempt to thwart efforts to make concealed carry by law abiding people a nation-wide reality. They have made people vulnerable at a time when they should be seriously thinking about, and preparing for, their own self protection. Not to become “vigilantes,” but to be able to hold the line against violence, until the professionals can respond. And, make no mistake, you are your own “First Responder.” Just as you would have a fire extinguisher in your home or car, or take a course in first aid and CPR, you need to consider how well you are prepared for the other kind of deadly threat that may suddenly present itself: a violent, criminal attack on you or those who depend on you. In this book, Massad Ayoob has brought together all the essential elements that you need to know if you are currently carrying concealed firearms or if you are considering doing so. This is your opportunity to take advantage of all of the research, knowledge and experience that Mas has accumulated over more than four decades. I can’t think of a better teacher.

This eShort is an excerpt from the Gun Digest Book of Concealed Carry. To learn more about guns, gear and tactics for concealed carry, visit gundigest.com.