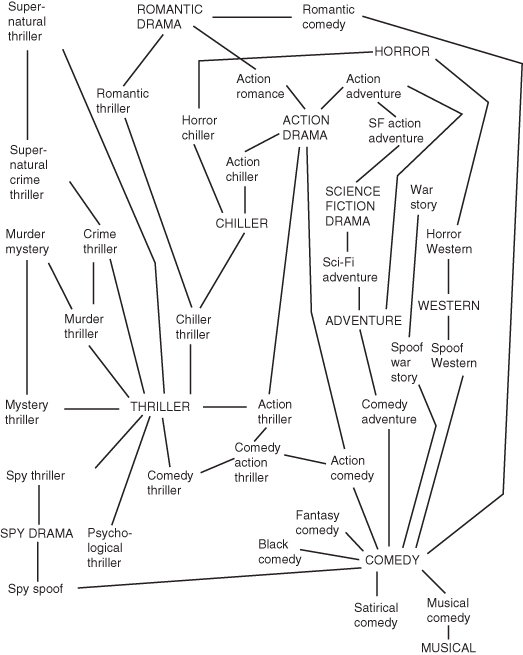

Figure 2.1 Film genre map.

(Courtesy of Daniel Chandler, Aberystwyth University.)

Chapter 2

Genre

Computer game publishers, game magazines, game review sites on the web, any text that discusses games, and millions of players around the world all love to put games in genres. You come across genre labeling all the time: games are shelved in shops by genres, and magazines label games in this way throughout their pages. It seems as if games have to belong to a genre.

It might seem that genres are the idiosyncratic manufacture of game reviewers and the marketing departments of publishers. This of course does happen on a regular basis and we found 389 genre names in current use, either frequently or spasmodically, by professional online game reviewers alone. But for a genre to become established as part of popular game culture it needs to go through a process of cultural acceptance so that all participants in a particular subculture—the players and industry professionals in this case—reach a collective agreement.

This collective conventionalization of genres is part of the general cultural and social construction of meaning systems; systems which allow us to understand and create within complex and often abstract communications systems that humans constantly invent and update. Computer games are just one example of such systems. So to better understand computer games, and for a number of other reasons which will become apparent as this chapter develops, genres are very interesting to study. But the foremost reason for starting our investigation into games with a discussion of game genres is the clear relationship genres have to the game development and publishing industry itself. We start where it starts; or rather, we start where the industry has gotten itself so far.

If you are a first-person shooter (FPS) fan then you will most likely be happy to play a new game loosely classified within that genre. You will find that the controls for the new game will be much the same as for other games of that type. You will use the same keyboard keys; WSAD to move and left mouse button to fire on the PC, for example, and similar control pad buttons to pick up and discard objects, and if there are differences they will be slight and easy to work out for players adept in the genre.

Genres are also one of the ways players can demonstrate that they are part of the computer gaming world. If you know what MMORPG 1 or RTS 2 stand for then you’re on your way. Game players themselves are pretty obsessed with genres in other ways too. Many students in Clive’s Games Futures class only played games from a small number of, often closely related, genres by choice; but they would recognize and be able to name games from many more. For the people who distribute and market games this seems great. Put a game in a genre and an established body of fans are ready and willing to try the game out just because it’s in a genre they love.

Of course one of the big complaints about genres is that they constrain publishers and make it difficult for new types of games and styles of gameplay to emerge. There are also other problems cited for genres.

Sometimes genres don’t seem to be quite as straightforward as players or the industry would like. Wreckless: The Yakuza Missions is a driving game, right? But Wreckless: The Yakuza Missions and Colin McRae Rally 2005 seem quite different despite the fact that you have to drive in both of them. They are very different games despite being in the same genre. How can that be? Maybe there is more to a driving game than driving. We’ll take a closer look at the driving genre later.

Perhaps we have become anesthetized to the notion of genre and have come to view it as some kind of marketing-speak that in the end is not very useful. But that does not have to be the case. There is a whole field of genre theory devoted to a wide range of communications media which attempts to understand what genres are and therefore the media themselves. Genre theory will be the first of the theories we study and apply to computer games.

The word “genre” comes from the French for “kind” and was used to refer to particular types of poetry, prose, and drama. Drama could then be classified as comedy or tragedy, for instance. Shakespeare referred satirically to classifications as “tragedy, comedy, history, pastoral, pastoral-comical, historical-pastoral, tragical-historical, tragical-comical-historical-pastoral …” (Hamlet, act 2, scene 2). The joke is well made but it also might give us an insight into the nature of genres. Is it possible to invent a completely new genre that doesn’t draw on an existing one? Can we find an instance in the history of the feature film, for instance, where a film was made which was then identified as being the first ever in a new genre? Or do new genres always adapt or amalgamate existing ones? In an established medium such as film, the latter is almost certainly the case these days. In the early days of film the former might have been possible.

Maybe games are new enough as a medium that new genres can still be invented. The rhythm action genre is perhaps the newest major genre to emerge from the games industry; a genre that is enabled, in some cases, by peripheral technology. Perhaps platforms such as the Nintendo Wii and the Xbox 360 Kinect system will make it easier to create new game genres, or will they simply be used to adapt existing ones?

We use genres extensively in everyday life. Research has shown that young children very soon learn to use genres in their conversations about the world around them (Jaglom and Gardner, 1981). Film and TV guides use genres extensively. The vast majority of us would have a pretty clear idea whether a film we were watching for the first time should be classified as a western, or a comedy, or a romantic-comedy, or a romantic-comedy-western; sounds familiar, doesn’t it. This also goes for TV programs that are new to us; most of us would have a clear idea of what a game show, a sitcom, or a soap opera should be like. What about reality TV as a TV genre? If reality TV is a TV genre, then what characterizes it?

Genres are a pretty powerful form of abstraction. They are a form of theory we employ in everyday life on a constantly recurring basis. So the first thing about genre is that it is a great example of a theory that we all use easily and understand in our everyday lives. It is no surprise then that we have come to use genres to classify games.

So, if it’s so easy and natural to use genres as a way of making sense of the mass of media surrounding us, it should be easy to define them? Now the trouble starts. Let’s further consider film genres. How do you define the “western” genre in feature films? You might say, all the films about cowboys. But there are films about cowboys that are not westerns. The Horse Whisperer and Midnight Cowboy are just two examples of many that come to my mind. I am sure you can think of your own.

We can try to refine our definition. Westerns are about cowboys, in the nineteenth century, in the United States. But lots of westerns aren’t about cowboys. They might be about building railroads, crossing and settling the Great Plains, wars between settlers and Native Americans, and so on. In fact, most characters in westerns aren’t cowboys at all.

The real point here is that we easily recognize genres but find it very difficult to define them. This is almost certainly because genres are just one example of the way our brains make sense of the world by finding patterns in the overload of stimuli that bombard us all in every waking moment. The pattern matching part of genres is not something that involves rational and conscious thought. This means that while we can work with genres and pretty easily identify examples of films that belong to them, most of the time we don’t actually know how we do it.

There is more to it than this. We have chosen the type of genres you might find in a TV film guide but there are other classifications for films that we would readily recognize as film genres. There is the “Hollywood” genre as opposed to “art movies” and “Bollywood,” for instance. This type of genre classification is not based on a theme or story type but on particular ways of making films. It means that the same film can be in several different genres. It all depends on your purpose in categorizing them. Not only are genres easy to recognize but difficult to define, they are also very much dependent on who is using the genre and what their purpose is in doing so. In film or in computer games, the genres we recognize and use were not just invented by a single person. They arise from a sort of dialogue that happens between people who make games and people who are entertained by them. The film genres most of us are familiar with have arisen over time by directors and critics using them and the film-going public accepting some and not others. So the fact that genres are a social construction is not a weakness but a strength. It means that genres in common use have a social value and are not just the arbitrary invention of a critic, well meaning or otherwise. In other words, the genres we recognize and use say something about how cultures view particular types of communications media. Therefore, game genres are fully rooted in culture and are not just marketing spin.

There are other strengths of genres. Despite the fact that they seem difficult to define in any rigorous sense there are some general principles we can establish for them. They are about both repetition and difference. It is the repetition of known features that allows us to establish which genre a film belongs to but it is the way that particular film differs from others in the same genre that makes it worth watching. It has to have the right type of things in common but has to be different in other respects. A film can’t just be a copy. It has to be different enough to be worth watching. Jurassic Park and its two sequels were so alike as to be more or less the same film, not just the same genre, and, to some of us, the sequels are less watchable for that very reason.

So when categorizing a film in terms of genre it is how that film differs from other films in the same genre that is perhaps most interesting about it, rather than the similarities it shares with them. And yet, to make sense of a particular type of action sequence, for example, we need to recognize it in terms of all the others we have seen.

In a film, we would all recognize the rescue sequence with alternating clips of, for instance, the cowboy on his galloping horse, the heroine clinging to a branch hanging over a cliff or waterfall. It only makes sense because we associate the cowboy’s haste with the heroine’s predicament. We don’t see the two scenes as being entirely separate. We instantly recognize this type of rescue scene because it is part of a general theory of film that we have learned over the years. This is not even specific to westerns. We recognize the type of scene but would expect all such rescue scenes to be different but similar. It’s part of the language of feature films.

The balance between repetition and difference in game genres is vital to game developers and players alike. It is one of the things we are going to try to use genre theory to identify. Although genres are so elusive in terms of definition we can still make good use of them.

Studying the genres people recognize can lead to insights concerning how they view a particular communications medium and what is important to them. Every genre positions those who participate in a particular medium as listener, reader, viewer, user, or player, each implying different possibilities for response and for action. Each genre provides a reader/player position for those who participate, a position constructed by the maker for the “ideal” reader or user. Computer games can do this very well (good games, that is). Part of the pleasure of games is that users feel they fit snugly into the “ideal player” position, as if the game developers had each one of them specifically in mind when they made it.

Such systems of genres can be seen as a practical way to help those who work in any mass medium to produce new content consistently and efficiently and to relate this production to the expectations of customers and users. Since the genre system is also a practical device for enabling individual media users to plan their choices, it can be considered as a mechanism for ordering the relations between the two main parties to mass communication: in our case, developers and players.

Recognizing a film as belonging to a particular genre identifies the viewer with other people who know enough about films to assign genres to them. The same is true with computer games genres; probably more so. Almost everyone watches films on TV even if they don’t go to the cinema. Fewer people play computer games and one way of identifying yourself as a member of this more select grouping is to know and use genres appropriately. One of the pleasures of game playing is being adept at particular genres. This has more significance to games and gamers than with many other communications media because to be fully adept with a game genre means you have to have certain skills and knowledge particular to it. Anyone can watch a film but you have to develop skills to play particular games effectively. Because of this, knowing and using game genres effectively acts as a sort of badge of membership of the games community.

In a straw poll conducted among Clive’s Games Futures students we asked everyone to put up their hand if they felt adept at one game genre. Not surprisingly, everyone put a hand up. We asked people to keep their hand up if they played games from two genres, then three, then four, five, six seven, eight, nine … by nine or ten we stopped the survey because no one still had a hand up. After six or seven the number of hands fell away dramatically. People seemed happy with up to about six or seven genres. Compare that to the genre map of TV films, and the picture is quite different. Although many people would have a number of favorite film genres almost everyone would be able to recognize and watch films in all the genres. With computer games, all the class would be able to recognize most if not all genres if they saw someone else playing them or saw them advertised on the television. But they only see themselves as adept at games from a relatively small number of genres. What does this tell us about game genres and can we use this to our advantage? Can this observation lead to a theory of game genres that will in turn lead to some insight into the nature of games? Yes, because the difference between recognizing a game genre and being an adept in it makes games genres very different from film genres.

As we already pointed out, a game genre will posit an “ideal player” and many players are happy to be able to recognize themselves as that ideal player. By choosing to play a particular game we are identifying ourselves with the kind of person the game maker was designing the game for. I believe the link between game developer and player is far more potent than the link between film director and film viewer. I don’t need new skills to watch a film from an unfamiliar genre but I certainly do to play a game in a genre I am unfamiliar with for the first time. It’s our first clue on the road to understanding games.

Before looking at computer game genres in detail, here is a technique we can make use of. For a given communications medium we can build up a genre map which charts the relationship between the main genres of a particular medium. Figure 2.1 is a map of film genres as found in TV listings magazines in 1993 (Chandler, 1997). It lists the genres of films that would be shared by film critics and TV viewers.

An important point about the genres that make up the map is that they are not just made up but drawn from actual TV film running schedules, so are socially recognized genres. Consider for a moment the nature of the genres represented in the map. The categorization implicit in the map is based on the notion of content, on the type of story being told and the conventions concerning the way the film should be made. The former relates to particular character types and plots while the latter are to do with the photography, lighting conventions, and so on that go with them.

The map also illustrates the point we made earlier about genres, and how new ones are made from existing ones. In other words, we can take the “science fiction” and “comedy” genres and make up a new one of “science fiction comedy” of which there are actually many examples (even though this genre does not appear in the map). No genre map such as this will ever be complete. There will always be films we had forgotten about or which haven’t been made yet. But as with genres in general, the genre map for a given communications medium can be a very useful tool. In fact, the genre map is a model, an approximation which helps us to visualize the theory of genres at work. There are things the model misses and maybe even gets wrong but it is useful nevertheless.

It’s actually quite difficult to work out what the underlying theory for this model is. Is it story type, or styles of camera work and lighting and acting? It is most likely a combination of all these and more. Again, we see how we understand and make use of the genre model without knowing exactly what the underlying theory is. Are game genres as elusive? If you take a look at a typical discussion, such as the one at Wikipedia (Game Genres) you would think so; but we know different.

We can try to build up a similar map for computer games genres by simply making a list of all the named genres we can find in, say, the online magazine IGN.com, and then working out the relationships between them; in other words, what genres appear closely related. Presumably we would end up with a similar map to the film one above. In fact, this is what we tried to do in my Games Futures classes. Making the list wasn’t too difficult but it wasn’t always easy to agree what was an “official” genre and what was not. It was all too tempting to just add in a genre or two of your own.

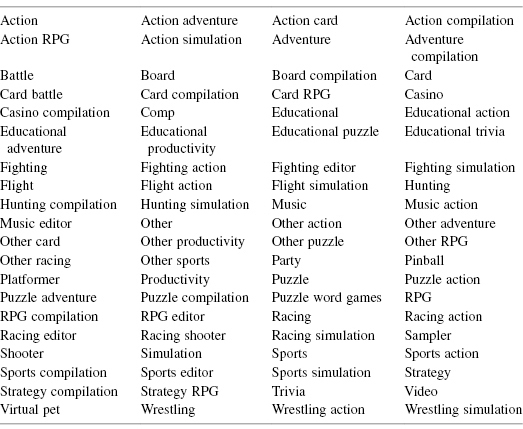

So what genres does the game industry recognize? Table 2.1 shows a fairly typical list of genres used by major game review sites. Most of the genres included seem reasonable but there are one or two oddities. For instance, racing is there but driving is not; not all drivers are racers nor are all racers drivers. Sneak-’em-ups are not mentioned, as are not a number of other genres we’ll use in this book. We’re sure you can all think of other omissions and anomalies.

Table 2.1 Game Genres

Now here are a couple of lists of game genres drawn up by people in the industry. First of all, we will include Steven Poole’s list of game genres from chapter 2 of his excellent book Trigger Happy (2004), which, incidentally, was the set book for the Games Futures module before we wrote this one; his genres are:

Andrew Rollings and Ernest Adams, in their equally excellent book on game design (2003), discuss the following genres in some depth:

The games “press” as a whole seem to recognize a lot more genres than these two writers on games. Why should this be so? The main reason is that the press is largely concerned with the way games are marketed and sold. Most games are designed to be in a particular genre because that is a major part of the way they will be reviewed and thus feed sales through to the major, mostly online, retailers. On the other hand, the game writers are trying to make some sense out of all these genres and whittle them down to a small, manageable set that seem coherent for the purposes of discussion and capture something of the nature of games. Is there a way we can make some useful sense out of all this?

We already noted an apparent difference between TV film genres and game genres. People were able to watch any number of film genres but were only adept at playing a few, typically six or seven, game genres. It is easy to see that this is because of the investment in knowledge and in particular skills that is required in order to become adept at a particular game. Very often being such an adept makes it fairly easy to play other games in the same genre. You will recognize the underlying logic of the game, how to progress and win. The interface will most likely be very similar, even down to the keyboard or game pad controls, and so on. Game genres are different from film genres.

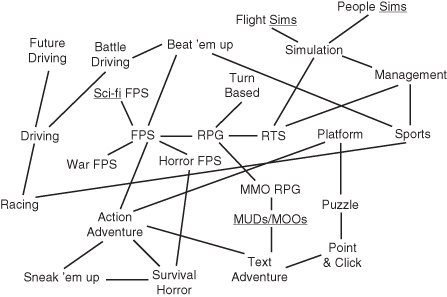

The kind of map we saw for TV film genres, Figure 2.1, did not appear to exist for games. Trying to build such maps begins to make the difference between game and film genres clearer. In Clive’s Games Futures classes building a genre map for games was one of the initial tasks for students. Figure 2.2 is a synthesis of some of the maps built by students and uses some of the genres they suggested. This one is much simplified but does exhibit some of the general ideas and some of the main problems encountered.

Figure 2.2 Genre map for games.

We should emphasizes that there is no correct genre map for computer games, but that certainly doesn’t mean that trying to make one isn’t interesting and useful because it certainly is.

You will find many of the genres in this map used by the games press, but student maps typically included far more genres than even the games press commonly uses. One of the reasons for this is that Clive did not require the students who constructed these genre maps to restrict themselves just to genres cited in published media. They created genres of their own to best reflect the way they categorized computer games. This led to much discussion concerning whether or not some of the entries in their maps were actually genres at all.

Looking at Figure 2.2 we might question the difference between horror–FPS and survival–horror. The latter is a recognized subgenre of action adventure but the former is an invention. Similarly, we could ask, are the two genres war–FPS and future–FPS from the map of game genres at all? We came to the conclusion that these were more like film genres and were just instances of FPS in general. So what is the difference?

Film genres are all to do with the type of story the film is based around and along with such stories come ideas about the style of lighting, camerawork, and a host of other things. Game genres are all concerned with activity: what does the player actually do in order to progress the game? This is why future–FPS and war–FPS are not actually game genres because the gameplay would be almost identical, and exactly what you would do in an FPS in general.

Here is an easy way to focus in on game genres. Pick a game genre or three—preferably ones closely related to one another as on one of the genre maps above—and try to write down a few verbs (six or so) which appear to capture the main activities which characterize the genre. In particular write down “doing words,” present participles, that attempt to characterize what you can expect to be doing at any one moment in a game of a given genre. This seems to break the rule we stated earlier that genres are easy to recognize but hard to define. Well, the idea here is not to define computer game genres precisely—we’ll do that in the next chapter—but rather to build a model that gives us some insights into the nature of these genres and thus, perhaps, the nature of computer games themselves.

Table 2.2 lists a range of game genres and the present participles associated with them. Basically, we have put forward a theory that activity characterizes game genres. Not all of the “ings” are action words; some are thought and emotion type words. Thinking and feeling are just as much central to game activities as more obvious actions. They are all at the heart of the pleasure of game playing and will lead us into the subject of aesthetics (in Chapter 4).

Table 2.2 A Basic Set of Genres

| Genre | Activities |

| FPS | Shooting, killing, moving, collecting, ambushing, camping |

| Stealth | Shooting, moving, attacking, collecting, waiting, hiding, puzzle solving, sneaking |

| 3D adventure | Moving, puzzle solving, collecting, speaking |

| Point and click | Moving, puzzle solving, collecting, speaking |

| Platform | Moving (scrolling), jumping over, jumping on (killing), avoiding, puzzle solving |

| RPG | Fighting, developing/training, exploring, traveling, investigating, story building, empathizing (with character) |

| Beat-’em-up | Fighting, tactics, countering, making moves |

| RTS | Building, commanding, fighting, planning, scouting, collecting (money, wood, etc.) |

| Driving | Steering, accelerating/decelerating, overtaking, avoiding, skidding, cornering, maneuvering, making pit stops, crashing |

| God games | Building, planning, strategizing, predicting |

| Retro | (No common activity words) |

However, for the moment we are interested in the way different gameplay activity profiles, that is, patterns of activity, not only characterize genres but also allow us to compare and contrast games in new ways. We can begin to make some interesting observations about certain game genres and the relationships individual games have with them. We already saw how this theory of game genres allows us to eliminate some of the instances in Figure 2.2 because they didn’t have distinct sets of activities. You should be able to go through the diagrams and eliminate or, rather, amalgamate more genres.

It is very interesting to consider the links between genres. Take a look at the links around the puzzle genre in Figure 2.2. Are we happy about these, for they would seem to imply a very strong link between puzzle and platform, action adventure, point and click, and text adventure? The problem here is the puzzle genre at the center of the relationship. All of these games have puzzling as a major activity but puzzle games are a lot simpler than the other four; there is a confusion between activity and genre.

The other four do cohere in terms of activity, particularly action adventure and platform, then text adventure and point and click, but all are realized in differing gameplay modes.

Notice there is no link between action adventure and RPG although there is a strong link between these two genres, particularly with games like Fable: The Lost Chapters. Basically, an RPG is an action adventure with significant character development skill enhancement as gameplay activities.

A further question: did RPGs evolve from from text-adventure as Figure 2.2 would seem to suggest? After text-adventure there were MUDs 3 and MOOs 4; the latter having significant character development—along with other forms of development—and both were certainly very influential on today’s MMORPGs, the temporal incarnations really differing on gameplay modes more than activity sets.

Other links in this vicinity would not seem to be quite as strong. That between RPG and RTS, for instance, does not seem right. The links between RPG and its various sub-genres do seem fair. It also seems clear that closely related genres on the map can have significantly different gameplay; sneak-’em-up/stealth and FPS are good examples of this.

The retro or classic genre doesn’t have any common activity words. It is not a genre in this classification. It could possibly be a genre if we were looking at genres concerned with the development of games over time, but not based on gameplay. However, characterizing some retro games can be interesting; for instance, “genre-ing” Lemmings puts it in the RTS genre, and it is therefore the ancestor of all RTS games.

We can also observe that genres evolve over time—genres as memes5—and this is clear if we observe the changing names of common genres. When Thief and similar games were first released they were termed sneak-’em-ups by the games press and the term was recognized and used by game players. Such games are now referred to as stealth games and the term sneak-’em-up seems to be largely forgotten and indeed unrecognized by younger players.

We can begin to think about subgenres. If you list a set of activities for a typical survival horror game such as Resident Evil 4 and an RPG action adventure game such as The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess, you will find the activities are much the same; it is the back-story that is distinct to Resident Evil and the addition of RPG elements that characterizes this version of Zelda. Perhaps game subgenres are about limited variations in either activity profiles or differences in other things such as back-story, rendering style, and so on.

It is interesting to look at another action adventure game in terms of genre to illustrate that genres are not as straightforward as the previous table would seem to suggest. As an action adventure game, Shenmue will indeed be characterized by the verbs exploring, puzzling, traveling, investigating, and so on, but it is also characterized by developing/training and high levels of confronting which are characteristic of RPG; in other words, genre-mixing. But at various stages in the game the genre switches to driver or beat-’em-up, among others. In this game we have differing activities to undertake at different stages in the game. Such genre switches mean that we can only fight people when it is appropriate to the story line. In Shenmue this is more than reasonable as it prevents us fighting old ladies and other innocent citizens who just happen to be passing while we are exploring or investigating. So Shenmue as an action adventure mixes in elements of RPG but is also a multi-genre game and employs genre-switching to vary the types of activity, the gameplay mode, required of the player at particular stages in the game.

Now let’s look at the driving genre and see how identifying the activities that characterize such games will lead us to new insights about this popular genre. Take the two games Wreckless: The Yakuza Missions and Colin McRae Rally 2005. They are obviously both drivers. The main activity is driving fast vehicles. But they are quite different games. In Wreckless we play either a spy or a police officer attempting to bring down the head of the Yakuza in Hong Kong. As the name suggests, the player’s objective is to thwart various Yakuza bosses by wrecking their transportation using the playable vehicle. This is not its only feature; it also includes strategy and action adventure activities in particular missions. For example, one case requires the player to rescue a hostage from a massive dump truck, but this cannot be done by simply ramming the vehicle. The player has to detonate explosive barrels the truck is carrying by launching the playable vehicle off various points around the construction site.

The verbs that describe this game are investigating, planning, and attacking, but these belong to the RTS genre and certainly don’t apply to Colin McRae Rally 2005. This is much more of a rally simulation and requires great driving skill on all sorts of terrains, following a codriver’s routing instructions, working within time constraints, and all sorts of other skills that belong to rally driving.

We have two drivers that have some of the same verbs but one, Wreckless, has some from another genre. Wreckless is a kind of strategy game, a driving–strategy perhaps? Perhaps the driving genre is really some kind of meta-genre in which we have the basic activity type of driving but to which can be added other activity types to arrive at specializations of it. Think of other drivers and see what specializations might apply to them: some are beat-’em-up–drivers, some are stealth–drivers, RPG–drivers, and so on.

The driver genre is indeed a meta-genre. Rollings and Adams have an even more inclusive meta-genre called vehicle-simulations which would include flight-sims, boat-sims, ship-sims, train-sims and many more. Some of the games in the retro or classic genre, Lunar Lander for instance, can also belong in this genre.

Genres are helpful and confusing all at the same time. Writers on games seem to want/need to adopt fewer, more generic genres in order to make sense of games as a phenomenon. It may well be that there is a trend here that has something to do with the evolution of games over time. In the beginning there were no genres. There was only a small number of games, most of which looked very different. As more games appeared you could perhaps begin to classify them: spaceship games, collect-’em-ups, and so on. Perhaps the first real genre was text adventure; but after that came the platform genre and suddenly everything before that was retro or classic. Platform was the first recognizable genre for graphics-based games. Now, with hindsight and a little genre analysis, we can see that even classic and retro games mostly belong to currently recognizable genres and that platform may well be an instance of adventure constrained by the technology of its time.

In games, gameplay activity is king! So, instead of starting with the genres the games press use, why not start with a small number of activities and classify games according to the patterns of activity that are important to them. We have done just this in an informal way in this chapter but even so have come up with some interesting insights into the nature of games by analyzing genres. We considered:

In the next chapter we are going to pick up on these ideas and develop a more practical approach by using software to analyze gameplay activities, allowing us to work with games and their genres in a far more rigorous manner and in far greater numbers.

If you would like to follow up on genre theory and discussions of game genres then here are a few starting points. The best introduction to genre theory I have found is Daniel Chandler’s An Introduction to Genre Theory (1997) which is part of his excellent “Semiotics for Beginners” site which we will be referring to again in Part II of this book. Good discussion of game genres, but not from a genre theoretic point of view, can be found in Steven Poole’s excellent Trigger Happy (2004, p. 29) and the whole of part II of Andrew Rollings and Ernest Adams’ excellent book (2007).

Here are some tasks to try for yourself:

Solutions to all tasks and exercises throughout this book can be found on the associated web site.

Notes

1 Massively multiplayer online role playing game.

2 Real-time strategy.

3 Multi-user dungeon.

4 MUD-object orientated.

5 This refers to cultural evolution of a classification over time.