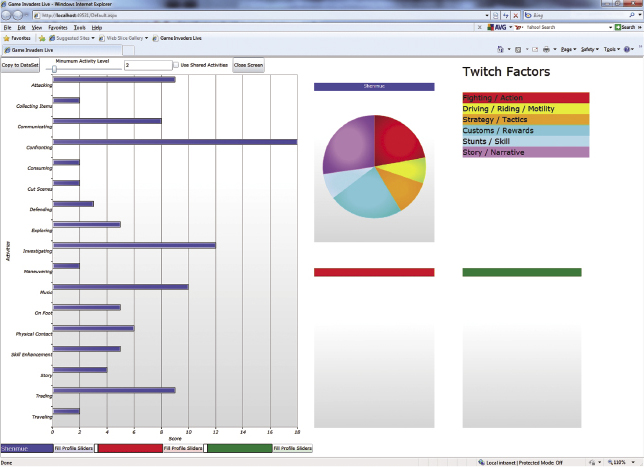

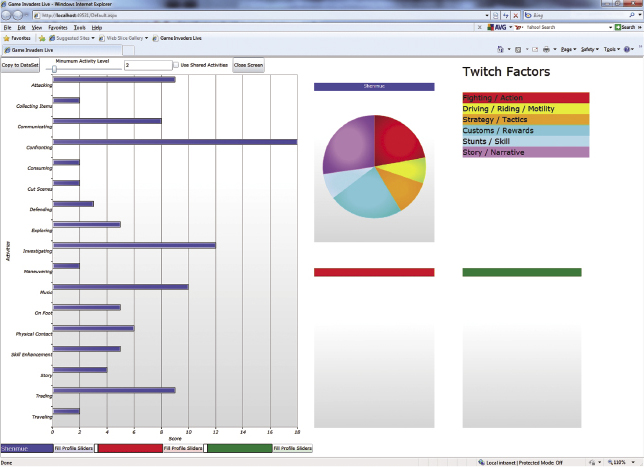

Figure 9.1 Activity profile for Shenmue on the Dreamcast.

Chapter 9

Time to Visit Yokosuka

Time now to travel to Yokosuka, in Japan, and visit someone Clive got to know quite well. His name is Ryo Hazuki; he is sixteen and has been having a rough time lately. Recently some people broke into his father’s dojo, where he taught a particular form of martial arts, and killed his father. Ryo was left alone in the world except for his ageing grandmother and has been on the trail of his father’s killers ever since. Clive has been helping Ryo out, as have tens of thousands of other people, most of whom, like Clive, have never been to Japan.

Yokosuka is across the bay, a very large bay, from Tokyo. It is also on the Dreamcast, which means it’s time to analyze one of our favorite games. We’ll use all the theories and models studied so far to analyze the game from various viewpoints and see what we can find out and how to put it all together.

On the back of the box—containing no less than three CDs for the game itself and a fourth for the online extras—we find the following: “Open your eyes to the most compelling form of interactivity ever experienced outside the real world. Shenmue is a passionate and gripping story, captured in a beautifully rendered 3D world, brought to life using ‘Magic Weather’ and ‘Time Control’ technologies. Interact with a huge cast of characters with movements as intricate as a twitch of a finger, experience real-time fighting and discover the host of online features available. This is clearly not a game but an experience never to be forgotten.”

This sounded great to Clive who, for one, certainly did find the experience memorable, and he is most definitely not alone. Of course we want to find out more about how the game works, why it works, and how it does and doesn’t differ from other games. Does it live up to its publicity blurb?

Shenmue is a quest in which the hero, Ryo Hazuki, has to find his father’s killers. To do this he becomes an amateur detective and must find out who knows anything about the events surrounding the murder. No one knows anything in great detail but there are lots of clues to be gathered by talking to the local people who all know Ryo very well. He is part of a very close-knit community who respected his father and family. Later in the game, Ryo’s investigations take him away from his local community and out into the big, bad world of Yokosuka and beyond.

The development of the game was produced and directed by Yu Suzuki who coined the term “full reactive eyes entertainment” (FREE) for the generic gameplay mode. In other words, the player should be able to do pretty much anything they would in the real world. You can follow the quest, or go shopping, talk to people, play on your Dreamcast, go to the amusement arcade, and so on.

From time to time Ryo comes up against baddies who are in some way connected with those who committed the murder and has to fight them in order to survive. All the clues Ryo uncovers and the contacts he makes are added to a notebook which can be referred to when necessary. He can also collect objects for later use, in true adventure fashion. There are many more activities for you to get Ryo to do in the game but we will go into those in detail when we consider agency.

Let’s first see how the press deals with Shenmue in terms of genre. Mostly they seem to classify it as action adventure but they encounter problems because of its genre-switching features; we discussed these in Chapter 2. So in some of the reviews you would think the game was an RPG; while in others you would think it was just a beat-’em-up and that all you did was wander around town until the next fight came along. Of course the fights do come along and you cannot avoid them but you won’t get anywhere in Shenmue if you just wait for them and do nothing else. In fact, if you don’t get out and about and talk to people the fights will not come along at all. Then there are also driving sequences and a lot of watching cut scenes. How does Shenmue match up as action adventure or an RPG even? Let’s check its activity profile, presented in Figure 9.1.

Figure 9.1 Activity profile for Shenmue on the Dreamcast.

The highest scoring activity is confronting, which is the only one to get a maximum score. There are then five middle ranking scores, in descending order: investigating, music, attacking, trading, and communicating. This is an interesting mix to say the least. Investigating, trading, and communicating all belong to strategy and tactics and are not only more measured activities but also very much what you do in the main FREE mode we just discussed. Attacking is of course very twitchy and quite in keeping with Shenmue’s fighting mode. It is, however, unusual for music to score so highly in this type of game, but it does make sense because music in Shenmue is tied in so closely to cut scenes, changes of time of day, mood changes, and so on.

This is interesting, as confronting and investigating are actually quite separate in the game. The main exploration and puzzle solving mode is very definitely action adventure or RPG: you can talk to people, collect items and information, and perform a whole range of other non-twitchy activities, but you can’t fight anyone. In other words, it is not action adventure. The action only comes out through the genre switching, which moves you to beat-’em-up or driving or a whole host of Quick Time Events (QTEs): Resident Evil also uses the latter, as we saw in Chapter 6. When you are going about town you cannot be aggressive. Later in the game we have to go to work and we are suddenly playing a driver—a forklift-truck-driver, to be exact. We gain agency typical of the driving genre at the expense of that offered by the adventure.

The lower-medium scoring activities, physical contact, exploring, on foot, skill enhancement, story, and defending, follow a similar pattern. We have physical contact and skill enhancement for the beat-’em-up sequences and communicating and trading for the predominant adventure/RPG sequences. In the adventure mode in particular there are lots and lots of things to do. Apart from exploring and talking to people, we have examining and purchasing inanimate objects; interacting with active objects such as doors, telephones, game consoles, and so on; buying food for and feeding a lost kitten; martial arts training; QTEs; watching cut scenes; and much more. The score of 4 for story supports this.

Finally, there are five activities scoring 2 that fill out the profile: collecting items, consuming, cut scenes, maneuvering, and traveling; all of which support the predominant adventure/RPG mode.

In fact, watching cut scenes is a very important part of the gameplay of Shenmue and we are often presented with this most passive of all activity types. We basically sit back and watch for seconds and even minutes at a time. There are no levels as such in Shenmue. The further aspects of the game open up when we have gathered enough information and defeated the requisite baddies in battle. Cut scenes come along depending on the point we have reached in progressing through the game, and often the time of day, for instance. We are switched into and out of the movie genre as we are the other genres that make up the game.

It is not surprising given the mix of activities in its profile and the importance of the switching in and out of the movie genre that Shenmue has a twitch factor of 0.8, which means its gameplay is quite measured even though the player is switched into very twitchy fight modes from time to time.

So Shenmue is an action adventure–beat-’em-up–driver–RPG–movie; that’s pretty clear, isn’t it? In fact, that is pretty clear. Shenmue combines a whole set of traditional, game-based activities in a classic quest using genre-switching. That makes for a very interesting package.

In Shenmue we, the player, direct the principal protagonist, Ryo Hazuki, in his endeavors to find his father’s murderers. Shenmue is a vast, interactive 3D virtual environment within which we have to search out clues that help Ryo in his amateur detective work. Aesthetically it is a very rich environment indeed so we will have much to discuss. There are also going to be some surprises; there have already been two: genre switching and movie watching.

First, of course, we consider agency and in particular intentions and perceivable consequences. We already noted in the section on genre that Shenmue employs genre switching which means that the nature of agency will depend on the genre or mode we are currently switched to. Our inclusion of the movie genre is also going to be substantiated as we study agency in Shenmue.

Imagine for a moment that we are in the main adventure genre, which offers us exploring, examining and purchasing inanimate objects, interacting with active objects such as doors, talking to people, and training. In the latter we practice moves for the times we are switched to beat-’em-up. The majority of agency in Shenmue is concerned with the first four. Despite the slight differences in their means of interaction, these four share a very interesting characteristic; they all reward our exercising agency with a prescripted action sequence (PSAS) which effectively, temporarily, removes the user’s ability to exercise agency.

For instance, in the basic act of opening a door we have the following sequence of events:

on the controller appears close to or over the door,

on the controller appears close to or over the door,There are several interesting points to note here. It is quite unusual for the physical interface, the controller in the form of a graphic representing the red A, to be represented within the game itself. It should be a shock that reminds us we are in an artificial environment. It would normally remind players that this world is mediated and that button presses are analogous to walking and running, for instance. This technique is used extensively in Shenmue and extended in the QTEs where agency is very simplified, an obvious abstraction of the real world. The fact that for the vast majority of players the red A is not a shock but an enhancement of gameplay points once again to the positive role unrealisms often play in games. The encroachment of the red A into the game world is also used to highlight possibilities for agency that are not obvious from the game logic the player has so far encountered.

We do not always know the PSAS we are to get. If the door is locked we might get Ryo’s thoughts; he might not want to knock because it is late and he does not want to disturb people. We might hear a request to “go away” from the other side of the door. This uncertainty of the outcome of exercising agency is used to great dramatic effect in Shenmue. Perceivable consequences and rewards are not always what we would desire or expect. False attractors can be great for gameplay.

Most interesting of all, though all from the above sequence, is that the perceivable consequence of exercising agency when in adventure mode—apart from when we are training—is always a prescripted, sometimes a prerendered, sequence. For instance, if we want to talk to someone, the perceivable consequence of pressing the red A when close to that person will be a question from Ryo followed by some sort of response, not necessarily helpful or polite, from the person he is speaking to. The conversation can often be continued by another press of the red A—after agency has been given back—which will result in another question and response.

Why is this so interesting? Well, in most computer games we would trigger a sensor or touch a switch and the door would open and we would walk through. We would type a question and wait for the response. But all this would be under our own volition and if we got in the way of the door we might accidentally stop it opening properly and perhaps be injured in the process. In Shenmue we lose control of the details of the act. Exercising agency is rewarded by removal of agency. The perceivable consequence is a cut scene.

As we have seen in the “opening door” sequence above, agency and POs are very closely linked. Let’s jump straight into POs at this point and investigate Shenmue’s strange form of agency further. Later on we will look at the wider ramifications.

What do we look for in Shenmue? What kinds of attractors tempt us into forming intentions? The main attractors are:

And all these are often associated with the red A. In fact, the strongest attractors in Shenmue are complex attractors where an attractor of the kind just listed is juxtaposed with a red A; there is always a strong element of mystery or fear or desire associated with these.

In a game such as Shenmue we would expect a range of connectors to help us stay focused, remind us of what our principal intention currently is, remind us what objects we currently possess, and so on. Shenmue is no exception. There is a clock that is always in the bottom right of the screen and shows Shenmue time—part of the “Time Control” system lorded on the back of the box. We often have to meet people at particular times and Ryo has to return home at a sensible time each night. Remember, he is a dutiful grandson. The clock is very useful. Shenmue time has some interesting characteristics, but more on that later.

We can always open Ryo’s notebook when in adventure mode and this lists clues we have discovered, phone numbers and addresses, questions we need to ask, appointments we need to keep, and so on. This comes in very handy; a great connector. Ryo also has a rucksack where he keeps a whole bunch of stuff he has collected or bought in the local shops; a typical adventure connector.

Another useful connector is the moped which Ryo can use to get around town faster and which also gives us another example of genre-switching, to driver this time. This saves time and keeps current intentions fresh in the mind. Otherwise we would have a lot of running around to do. Later on Ryo has to get the bus to the docks. Public transport is supposed to make connections, after all. Apart from these major connectors there are also the more usual ones of streets and pavements, shops, and other landmarks that guide and help us around town.

Let’s move on to rewards. We already mentioned these when we discussed the “opening door” sequence. Rewards result from the perceivable consequences of trying to satisfy our intentions. In Shenmue they can be:

Many of the rewards in Shenmue are social; the game is a highly social space and one which is far more complicated than the “physical” space of the various neighborhoods of Yokosuka. But rewards are not the PSAS themselves, though they can be if the perceivable consequence is an extended cut scene. Rewards are what we make of perceivable consequences, what we find significant in them, and what leads us to select a new attractor to set the cycle off again.

We have not finished with POs or aesthetics for that matter yet. We will deal with choice points, challenge points, narrative potential, co-presence, and so on a little later after we have considered PSAS and cut scenes as perceivable consequences and their influence on gameplay a little more.

Let’s make the distinction between PSAS and cut scenes clear. A PSAS is a short, prescripted action sequence, up to a few seconds long, that results from our exercising agency. It could be Ryo opening a door, or a question and answer session, for instance. Traditionally, a cut scene is a longer, usually prerendered sequence that offers information that will progress the storyline. They are similar but play different roles in Shenmue. PSAS are so integrated within the exercise of agency in Shenmue that many players do not realize they exist until they are explicitly pointed out. The only times that we are offered direct action in Shenmue are when:

On a historical note PSAS were not new to Shenmue. They are actually the basis of the gameplay in standard beat-’em-ups where particular button press combinations trigger particular martial arts moves. In this way, PSAS go way back into the history of games.

Perhaps the opportunities for direct action are included as a kind of temporary respite from the PSAS and cut scenes. They give us more direct control but only when the Shenmue game logic allows it. Perhaps Shenmue is saying therefore that agency and narrative do not mix. This observation has been made by a number of people. The game is a story after all. We do not share that observation, as will quickly become clear.

There is another view. Perhaps what we have got in Shenmue is agency with integrated micronarrative components (PSAS) and that these support the more normal use of cut scenes proper, as is the case with other game types exemplified by Driver, Thief, and Unreal. All these games use cut scenes in a traditional videogame manner to put levels in context and tie in the next level or major level subsection, as is the case with Driver. The makers of Unreal 2, for instance, state quite categorically that “the story line is not allowed to get in the way of the action.” In that game each level is introduced by an “interactive cut scene” in which we have to talk to our support staff on the spaceship and find out about our next mission. When the level starts we are straight back into the FPS.

However, this is not the case with Shenmue. Cut scenes are activated at the user’s command as a result of navigation and agency in general. There are many cut scenes in Shenmue but they are integrated into the gameplay which does not have recognizable levels. In fact, Shenmue leads us on a subtle dance, which involves offering agency and then taking it away—by a PSAS—because we exercised it. We are allowed to explore in our own time and, usually, to choose when and whether or not to exercise agency, but the perceivable consequence is a PSAS. There are other times when a cut scene is imposed on us, because of the game logic, rather than a direct response to agency. For instance, we get to a particular warehouse in the docks after trying to find it and then finding a way to sneak past the security guards and are rewarded by a beautiful cut scene in which we meet someone we have only spoken to on the phone. This person passes on a lot of very useful information. The scene is prerendered, using the game engine, and lasts quite a long time. We are switched to movie.

There are also little cut scenes where nothing much happens, which are very filmic, which we do not initiate but which tell us for instance that night has arrived—a tracking shot of the skyline at night, perhaps with the rain falling if that is part of the current “Magic Weather” pattern.

In fact, PSAS and these little interludes build up suspense as we anticipate new revelations regarding the protagonists. In this sense PSAS and miniature cut scenes can be seen in some way as analogous to the variety of shots which build up scenes in films. We are happy to sit back and watch a major cut scene because we are used to watching PSAS and mini cut scenes. This is the way narrative and agency actually work together in Shenmue.

Shenmue also makes use of interactive variations on the PSAS idea. Quick Time Events (QTEs), for instance, occur in certain situations and require us to recognize an icon representing a particular button on the game controller flashed up on the screen, and then press the actual game controller button within a fraction of a second. We usually get several goes at this until we get it right. Examining, picking up, and buying objects also works in a similar way to an interactive PSAS.

There are several forms of interactive PSAS:

The various forms of PSAS are thus:

There is even a game in the amusement arcade where we can practice our rapid response skills for QTEs.

We can see that PSAS, miniature cut scenes and cut scenes proper play an important role in the gameplay of Shenmue. Now we will think more about Shenmue as a story.

In Shenmue, narrative is at the very heart of the basic units of gameplay as we have clearly demonstrated in the previous sections of this chapter. Agency is rewarded with narrative fragments. Multiple acts of agency are rewarded with the buildup of more and more of these fragments all of which in their own way contribute to the narrative potential of the game. Unlike typical shoot-’em-ups and sneak-’em-ups, narrative components are not simply used to frame individual levels or major subsections of levels. Narrative components are integrated into the game through the exercise of agency.

One of the consequences of this interplay of agency rewarded by narrative fragments is that the game can use extended cut scenes to introduce more substantial narrative material without interrupting the flow of the game. We are simply getting a bigger reward. Cut scenes can also be introduced for other reasons than agency.

The ambiguity of the meaning of the red A in the game space is part of Shenmue. Although it always indicates an opportunity to exercise agency, the reward for exercising that agency is not predictable. It is also an unrealism—a specifically designed infidelity. The red A attractors offer interesting possibilities, which help to establish narrative potential.

The streets and byways of Dobuita, for instance, offer a spatial maze, in much the same way as does a traditional shoot-’em-up, but the true conceptual labyrinth (Murray, 1997) of Shenmue is a social one. There is an entangled web or rhizome of social interconnections that we have to uncover in order to progress and make sense of the quest Ryo has embarked on. There are a number or beneficial routes through this social maze and a subset of the opportunities offered by the red A act as way-finders, which only become apparent through social interaction. At any moment we are offered a number of potential red As, constant and multifarious choice points.

Narrative potential arises from the juxtaposition of POs, the basic units of agency. In Shenmue we are constantly confronted by choice points. We are almost overwhelmed by choices and spend a lot of time in the beginning knocking on doors and talking to everyone before we realize that our interactions need to be more structured. The only people worth talking to once we have gotten going in the game are the people whose names we are given as maybe having something useful to say to us.

We also eventually come up against challenge points—problems we have to solve in order to progress with the quest. Finding the phoenix mirror is a classic example:

A classic challenge point, but did the extra light from the light bulb cause the scratch marks on the floor to become visible? However, scrutinizing the scratch marks on the floor enables a red A which offers a PSAS if the red A is pressed.

Co-presence is a major aesthetic pleasure of Shenmue. Talking to people and discovering the different characters, as well as the information they may or may not have, is a major pleasure of Shenmue. It is also one of the main reasons for the rich levels of connotation in Shenmue because conversations and therefore language play a central role in the information space of the game.

How closely do we associate ourselves with Ryo? As a player one feels more distance between oneself and Ryo than one does with the characters we take on in Unreal or Thief. In Shenmue it is not really the player but the player in the sense of Gibson’s “sensorium” (Gibson, 1984) or in the film Being John Malkovich. The player is not Lara Croft, nor is he/she Ryo. Somehow the player is more of a puppet master who is going to help and enable Ryo to achieve his quest. This is a clear case of transformation. How will Ryo think? How would he behave in this culture, which is so alien to most English players, but not to Ryo? This is not the player pretending to be Luke Skywalker but trying to put him/herself in Ryo’s shoes in order to try and see the world from his point of view. In this sense Ryo, or rather his character traits, become a sort of filter on the world of the game we perceive and on our ability to exercise agency in it. Ryo’s character is a prosthetic consciousness that is our only way of perceiving this alien world. There is thus a dramatic difference between the character we play in Shenmue and the character we play in Unreal. We are truly role-playing in Shenmue. However, because we do not develop the character ourselves this is not an RPG in the video game tradition.

In general, there appear to be two types of transformation:

In Thief, the player is the protagonist as a human who has strapped on a cyborg, steampunk exoskeleton. In Shenmue the player is not Ryo but Ryo’s motivational essence. Ryo is the protagonist, not the player.

Despite the extensive reliance on agency, Shenmue has many of the characteristics of narrative. We have a plot based around the quest, a film genre (the detective story), we have characterization, and we have a beautiful evocation of not only the architecture of neighborhoods but also of the extensive social relationships which are the true heart of those neighborhoods. In Shenmue we have all these characteristics of narrative existing side by side with agency.

Clive has never been to Japan and so exploring a “typical” Japanese neighborhood was fascinating for him. Yamanose actually reminded him of the kind of rural sprawl you find in many parts of Spain, for instance the areas just back from the coast near Gandia or Valez-Malaga.

Another of the pleasures of Shenmue is that it can also be a family or group experience; one person has the controller but everyone joins in with problem solving and exploration. Immersion/presence do not mean you have to be directly in control, just that you know this is happening right now and what happens next is up to you.

Learning is an important aesthetic pleasure of games in general. In Shenmue learning is of course important:

We also have to learn:

The guy who runs the hotdog stand is helpful with directions. Some people are more likely to help us with the current question of “Where can I find a bar where sailors go?” There is a small risk involved in talking to people, many of whom do not want to talk and can be quite rude. This is actually quite amusing and actually constitutes a realism but our reaction to it is different from what our reaction would be in real life.

A few thoughts on shocks and unrealisms. Conversations are segmented and triggered by pressing the red A. The physical interface intrudes into the game space in a way which is quite unusual. One would think, for instance, that the intrusion of the red A into the perceptual space of the game would be counterproductive for presence—reminding us of the mediated nature of our actions—but this does not appear to be so.

Time passes far more quickly than in real life, an unrealism because it helps the gameplay. Depending on how quickly the player gets through the game or when they have certain conversations they may have to wait for considerable amounts of time. Wasting time can be best achieved by practicing fight moves, shopping, or playing in the games arcade. In these situations time passes even faster in Shenmue time.

Realisms abound in Shenmue:

There are also definite shocks in Shenmue:

The fact that Ryo always asks the current question—or a version of it—can be strange, a shock, because there are times when you want to ask someone a previous question that you didn’t get a chance to ask before. In a similar manner, there is a point at which you would like to thank Nazumi for the flowers but are not able to because of the encounter with the drunk and the problems at the Asis Travel Agency.

One of the interesting things about new communications channels such as videocassette or DVD is the way in which they change existing artifacts. The film Blade Runner achieving its cult status as a result of its release on videocassette is a fascinating example. Why? Because its release on videocassette gave the viewer agency, which allows the viewer to interrupt the director’s flow of scenes and cuts and thus investigate the film at his or her leisure, speed, and ordering. Such agency disrupts the original narrative form and turns it into an interactive mystery. The viewer can try and find out about the origami unicorn and other such figures, and can observe the mysterious red-eye effect seen in replicants and wonder whether Deckard therefore is a replicant. There are levels of meaning which remain largely inaccessible if we cannot disrupt the directorial narrative flow. But this does not invalidate the film as a film. We can and do always go back to view the film as the director intended in real time.

Blade Runner the film gave rise to Blade Runner the game, a classic point-and-click adventure that is a predecessor to Shenmue. The authors believe that Shenmue did in turn redefine the computer game by finding a way to integrate agency and narrative so successfully. We may well be talking about the virtual storytelling genre in the very near future. In its way, Shenmue raises the same questions as Rez, for instance, “Can computer games appeal to more sophisticated aesthetic pleasures than those offered by an FPS or a beat-’em-up?” I believe the answer is the same, “Yes!”—but for differing reasons.

One further point before finishing this chapter. At the end of the previous chapter we made the point that much of what we have been talking about here remains unanalyzed by the methods and theories we are working with. Toward the end of the previous chapter we observed that much of what allows us to make sense of a game like Driver relies on what we already know about the United States, organized crime, and so on. Of course, much of what we know will come from TV and films and not from any direct knowledge of or contact with gangsters. The same is true for Shenmue for Clive, who has never been to Japan. In order to make sense of such things, to make meaning out of them, we bring into play the knowledge and meaning-making strategies we use in the real world. It will be interesting to investigate the relationship between these and the theories introduced so far. That is the subject of the next two chapters; a significant further outcome will be an overall theory for video games. Read on.

All the references for POs and so on were given in the previous two chapters. As for tasks? We are sure you know what to do now. Continue with the SimCity Classic case study:

We will return to the OpenCity case study at the end of the next chapter.