BOOK V

The Raft of Odysseus

Dawn from her couch by high Tithonus rose to bring light to immortals and to men;

20 and now the gods sat down to council. With them was Zeus, who thunders from on high, whose power is over all; and to them Athene, ever mindful of Odysseus, told of his many woes; for she was troubled by his stay at the dwelling of the nymph.

“O Father Zeus, and all you blessed gods that live forever, never again let sceptered king in all sincerity be kind and gentle, nor let him in his mind heed righteousness. Let him instead ever be stern and work unrighteous deeds; since none remembers princely Odysseus among the people whom he ruled, kind father though he was. Upon an island now he lies, deeply distressed, at the hall of the nymph Calypso, who holds him there by force. No power has he to reach his native land, for he has no ships fitted with oars, nor crews to bear him over the broad ocean-ridges. Now, too, men seek to slay his darling son, as he sails home. He went away for tidings of his father, to hallowed Pylos and to sacred Lacedaemon.”

Then answering, said cloud-gathering Zeus: “My child, what word has passed the barrier of your teeth? For was it not yourself proposed the plan to have Odysseus crush these men by his return? As for Telemachus, aid him upon his way with wisdom,—as you can,—that he may come unharmed to his own native land, and the suitors in their ship may be turned back again.”

He spoke, and said to Hermes, his dear son: “Hermes, since you in all things are my messenger, tell to the fair-haired nymph our steadfast purpose, that hardy Odysseus shall set forth upon his homeward way, not with gods’ guidance nor with that of mortal man; but by himself, beset with sorrows, on a strong-built raft, he shall in twenty days reach fertile Scheria, the land of the Phaeacians, who are kinsmen of the gods. There shall they greatly honor him, as if he were a god, and bring him on his way by ship to his own native land, giving him stores of bronze and gold and clothing, more than Odysseus would have won from Troy itself, had he returned unharmed with his due share of spoil. Thus, then, it is his lot to see his friends and reach his high-roofed house and native land.”

So he spoke, and the guide, the killer of Argus, did not disobey; forthwith under his feet he bound his beautiful sandals, immortal, made of gold, which carry him over the flood and over the boundless land swift as a breath of wind. He took the wand with which he charms to sleep the eyes of whom he will, while again whom he will he wakens out of slumber.

21 With this in hand, the powerful killer of Argus began his flight. On coming to Pieria, out of the upper air he dropped down on the deep and skimmed along the water like a bird, a gull, which down the fearful hollows of the barren sea, snatching at fish, dips its thick plumage in the spray. In such a way, through the multitude of waves, moved Hermes. But when he neared the distant island, there turning landward from the dark blue sea, he walked until he came to a great grotto where dwelt the fair-haired nymph. He found she was within. Upon the hearth a great fire blazed, and far along the island the fragrance of cleft cedar and of sandal-wood sent perfume as they burned. Indoors, and singing with sweet voice, she tended her loom and wove with golden shuttle. Around the grotto, trees grew luxuriantly, alder and poplar and sweet-scented cypress, where long-winged birds had nests,—owls, hawks, and sea-crows ready-tongued, that ply their business in the waters. Here too was trained over the hollow grotto a thriving vine, luxuriant with clusters; and four springs in a row were running with clear water, making their way from one another here and there. On every side soft meadows of violet and parsley bloomed. Here, therefore, even an immortal who should come might gaze at what he saw, and in his heart be glad. Here stood and gazed the guide, the killer of Argus.

Now after he had gazed to his heart’s fill on all, straightway he entered the wide-mouthed grotto, and at a glance Calypso, the heavenly goddess, failed not to know it was he; for not unknown to one another are immortal gods, although they have their dwellings far apart. But sturdy Odysseus he did not find within; for he sat weeping on the shore, where, as of old, with tears and groans and griefs racking his heart, he watched the barren sea and poured forth tears. And now Calypso, the heavenly goddess, questioned Hermes, seating him on a handsome, shining chair:

“Pray, Hermes of the golden wand, why are you come, honored and welcome though you are? You were not often with me before. Speak what you have in mind; my heart bids me to do it, if I can do it and it is a thing that can be done. But follow me first, and let me give you entertainment.”

So saying, the goddess laid a table, loading it with ambrosia and mixing ruddy nectar; and so the guide, the killer of Argus, drank and ate. But when the meal was ended and his heart was stayed with food, then thus he answered her and said:

“Goddess, you question me, a god, about my coming here, and I will truly tell my story as you bid. Zeus ordered me to come, against my will. Who of his own accord would cross such stretches of salt sea? Interminable! And no city of men at hand to make an offering to the gods and bring them chosen hecatombs! Nevertheless the will of aegis-bearing Zeus no god may cross or set at naught. He says a man is with you, the most unfortunate of all who fought for Priam’s town nine years and in the tenth destroyed the city and departed home. They on their homeward way offended Athene, who raised ill winds against them and a heavy sea. Thus all the rest of his good comrades perished, but wind and water brought him here. This is the man whom Zeus now bids you send away, and quickly too, for it is not ordained that he shall perish far from friends; it is his lot to see his friends once more and reach his high-roofed house and native land.”

As he said this, Calypso, the heavenly goddess, shuddered, and speaking in winged words she said: “Hard are you gods and envious beyond all to grudge that goddesses should mate with men and take without disguise mortals for lovers. Thus when rosy-fingered Dawn chose Orion for her lover, you gods that live at ease soon so begrudged him that at Ortygia chaste Artemis from her golden throne attacked and slew him with her gentle arrows. Again when fair-haired Demeter,

u yielding to her heart, met Jason in the thrice-ploughed field, not long was Zeus unmindful, but hurled a gleaming bolt and laid him low.

22 So again now you gods grudge me the mortal tarrying here. Yet it was I who saved him, as he rode astride his keel alone, when Zeus with a gleaming bolt smote his swift ship and wrecked it in the middle of the wine-dark sea. There all the rest of his good comrades perished, but wind and water brought him here, I loved and cherished him, and often said that I would make him an immortal, young forever. But since the will of aegis-bearing Zeus no god may cross or set at naught, let him depart, if Zeus commands and bids it, over the barren sea! Only I will not aid him on his way, for I have no ships fitted with oars, nor crews to bear him over the broad ocean-ridges; but I will freely give him counsel and not hide how he may come unharmed to his own native land.”

Then said to her the guide, the killer of Argus: “Even so, then, let him go! Beware the wrath of Zeus! Let not his anger by and by grow hot against you!”

So saying, the powerful killer of Argus went his way, while the potent nymph hastened to brave Odysseus, obedient to the words of Zeus. She found him sitting on the shore, and from his eyes the tears were never dried; his sweet life ebbed away in longings for his home, because the nymph pleased him no more. Yet being compelled, he slept at night within the hollow grotto as she desired, not he. But in the daytime, sitting on the rocks and sands, with tears and groans and griefs racking his heart, he watched the barren sea and poured forth tears. Now drawing near, the heavenly goddess said:

“Unhappy man, sorrow no longer here, nor let your days be wasted, for I at last will freely let you go. Come, then, hew the long timbers and fashion with your axe a broad-beamed raft; build a high bulwark round, and let it bear you over the misty sea. I will supply you bread, water, and the ruddy wine you like, to keep off hunger; I will provide you clothing and will send a wind to follow, that you may come unharmed to your own native land,—if the gods will, who hold the open sky, for they are mightier than I to purpose or fulfill.”

As she said this, long-tried royal Odysseus shuddered, and speaking in winged words he said:

“Some other purpose, goddess, you surely have in this than aid upon my way, when you thus bid me cross on a raft that great gulf of the sea—terrible, toilsome—which trim ships cannot cross, although they speed so fast, glad in the breeze of Zeus. But I will never, notwithstanding what you say, set foot upon a raft till you consent, goddess, to swear a solemn oath that you are not meaning now to plot me further woe.”

He spoke; Calypso, the heavenly goddess, smiled, caressed him with her hand and spoke thus, saying:

“A cunning rogue you are, never inclined to folly! How could you think of uttering such words! Hear this, then, Earth, and the broad Heaven above, and thou down-flowing water of Styx,—which is the strongest and most dreaded oath among the blessed gods,—I am not meaning now to plot you further woe. No, I have that in mind, and that I here propose, which I would seek for my own good were such need laid on me. Indeed, my thoughts are upright: no iron heart is in my breast, but one of pity.”

So saying, the heavenly goddess led the way in haste, and he walked after in the footsteps of the goddess. And now to the hollow grotto came the goddess and the man, who sat him down upon the chair whence Hermes had arisen. The nymph then set before him all food to eat and drink which are the meats of men, and took her seat facing princely Odysseus, while maids set forth for her ambrosia and nectar; then on the food spread out before them they laid hands. So after they were satisfied with food and drink, then thus began Calypso, the heavenly goddess:

“High-born son of Laeärtes, ever-scheming Odysseus, do you so wish to go at once home to your native land? Farewell, then, even so! But if at heart you knew how many woes you must endure before you reach that native land, you would remain with me, become the guardian of my home, and be immortal, despite your wish to see your wife, whom you are always longing for day after day. Yet not inferior to her I count myself, either in form or stature. Surely it is not likely that mortal women rival the immortals in form and beauty.”

Then wise Odysseus answered her and said: “O lady goddess, be not wroth at what I say. Full well I know that heedful Penelope, compared with you, is poor to look upon in height and beauty; for she is human, but you are an immortal, young forever. Yet even so, I wish—yes, every day I long—to travel home and see my day of coming. And if again one of the gods shall wreck me on the wine-dark sea, I will be patient still, bearing within my breast a heart well-tried with trouble; for in times past much have I borne and much have toiled, in waves and war; to that, let this be added.”

As he thus spoke, the sun went down and darkness came; and going to the inner chamber of the hollow grotto, they stayed together for the happy night.

Soon as the early rosy-fingered dawn appeared, quickly Odysseus dressed in coat and tunic; and the nymph dressed herself in a long silvery robe, finespun and graceful, she bound a beautiful golden girdle round her waist, and put a veil upon her head. Then she prepared to send forth brave Odysseus. She gave him a great axe, which fitted well his hands; it was an axe of bronze, sharp on both sides, and had a beautiful olive handle, strongly fastened; she gave him too a polished adze. And now she led the way to the island’s farther shore where trees grew tall, alder and poplar and sky-stretching pine, long-seasoned, very dry, that would float lightly. When she had shown him where the trees grew tall, homeward Calypso went, the heavenly goddess, while he began to cut the logs. Quickly the work was done. Twenty in all he felled, and trimmed them with the axe, smoothed them with skill, and leveled them to the line. Meanwhile, Calypso, the heavenly goddess, brought him augers, with which he bored each piece and fitted all, and then with pins and crossbeams fastened the whole together. As when a man skillful in carpentry lays out the deck of a broad freight-ship, of such a size Odysseus built his broad-beamed raft. He raised a bulwark, set with many ribs, and finished with long timbers on the top. He made a mast and sail-yard fitted to it; he made a rudder, too, with which to steer. And then he caulked the raft from end to end with willow withes, to guard against the water, and much material he used. Meanwhile, Calypso, the heavenly goddess, brought him cloth to make a sail, and well did he contrive this too. Braces and halyards and sheet-ropes he set up in her and then with levers heaved her into the sacred sea.

The fourth day came, and he had finished all. So on the fifth divine Calypso sent him from the island, putting upon him fragrant clothes and giving him a bath. A skin the goddess gave him, filled with dark wine, a second large one full of water, and provisions in a sack. She put upon the raft whatever delicacies pleased him and sent along his course a fair and gentle breeze. Joyfully to the breeze royal Odysseus spread his sail, and with his rudder skillfully he steered from where he sat. No sleep fell on his eyelids as he gazed upon the Pleiads, on Booätes which sets late, and on the Bear which men call Wagon too, which turns around one spot, watching Orion, and alone does not dip in the Ocean-stream; for Calypso, the heavenly goddess, bade him to cross the sea with the Bear upon his left. So seventeen days he sailed across the sea, on the eighteenth there came in sight the dim heights of Phaeacia, where nearest him it lay. It seemed a shield laid on the misty sea.

But now the mighty Earth-shaker, coming from Ethiopia, spied him afar from the mountains of the Solymi;

v for Odysseus came in sight as he sailed along the sea. And Poseidon grew more angered in spirit, and shaking his head he muttered to his heart:

“Aha! so then the gods have changed their plan about Odysseus, while I was with the Ethiopians! And here he is close to the land of the Phaeacians, where he is destined to escape from the ending of the woe that follows him. Yet still I hope to plunge him into sufficient ill.”

So saying, he gathered clouds and stirred the deep, grasping the trident in his hands; he started tempests of wind from every side, and covered with his cloak both land and sea; night broke from heaven; forth rushed together Eurus and Notus, hard-blowing Zephyrus, and sky-born Boreas,

w rolling up heavy waves. Then did Odysseus’ knees grow feeble, and his very soul, and in dismay he said to his stout heart:

“Ah, woe is me! What will become of me at last? I fear that all the goddess told was true, when she declared that on the sea, before I reached my native land I should have my fill of sorrow. Now all is come to pass. Ah, with what clouds Zeus overcasts the outstretched sky! He stirred the deep, and tempests wind hurry from every side. Swift death is sure! Thrice, four times happy Danaaäns who in the time gone by fell on the plain of Troy to please the sons of Atreus! Would I had died there too, and met my doom the day the Trojan host hurled at me bronze spears over the body of the son of Peleus! Then had I found a burial, and the Achaeans had borne my name afar. Now I must be cut off by an inglorious death.”

As thus he spoke, a great wave broke on high and madly plunging whirled his raft about; far from the raft he fell and sent the rudder flying from his hand. The mast snapped in the middle under the fearful tempest of opposing winds that struck, and far in the sea canvas and sail-yard fell. The water held him long submerged; he could not rise at once after the crash of the great wave, for the clothing which divine Calypso gave him weighed him down. At length, however, he came up, spitting from his mouth the bitter brine which plentifully trickled also from his head. Yet even then, spent as he was, he did not forget his raft, but pushing on amid the waves laid hold of her, and in her middle got a seat and so escaped death’s ending. But her the great wave drove along its current, up and down. As when in autumn Boreas drives thistleheads along the plain, and close they cling together, so the winds drove her up and down the deep. One moment Notus tossed her on for Boreas to drive; the next would Eurus give her up for Zephyrus to chase.

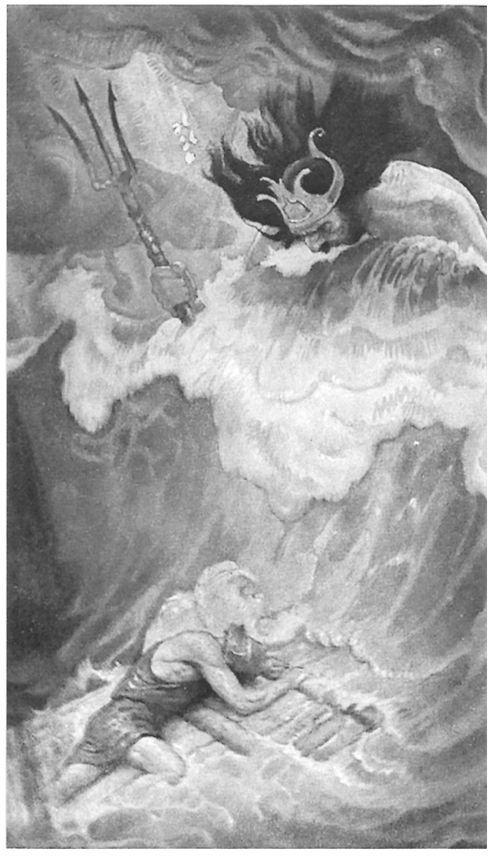

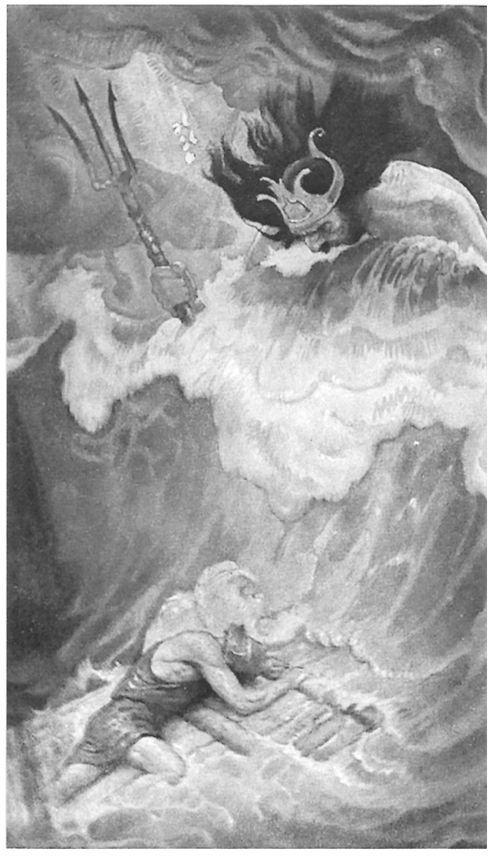

The Raft of Odysseus—from a painting by N.C. Wyeth

But the daughter of Cadmus saw him, fair-ankled Ino, that goddess pale who formerly was mortal and of human speech, but now in the water’s depths shares the gods’ honors.

23 She pitied Odysseus, cast away and meeting sorrow, and like a sea-bird on the wing she rose from the sea’s trough, and lighting on his strong-built raft spoke to him thus:

“Unhappy man, why is earth-shaking Poseidon so furiously enraged that he makes many ills spring up around you? Destroy you shall he not, however furious he be! Only do this,—you seem to me not to lack understanding. Strip off these clothes, and leave your raft for winds to carry. Then strike out with your arms and seek a landing on the Phaeacian coast, where fate allows you safety. Here, spread this veil underneath your breast. It is immortal; have no fear of suffering or death. But when your hands shall touch the shore, untie and fling the veil into the wine-dark sea, well off the shore, yourself being turned away.”

Saying this, the goddess gave the veil, and she herself plunged back into the surging sea, in likeness of a sea-bird. The dark wave closed around. Then hesitated long-tried royal Odysseus, and in dismay he said to his stout heart:

“Ah me! I fear that here again an immortal plots me harm in bidding me leave my raft. I will not yet obey; for in the distance I saw land, where it was said my safety lies. This I will do, for best it seems: so long as the beams hold in the fastenings, here I will stay and bide what I must bear; but when the surge shatters my raft, then I will swim. There is no better plan.”

While he thus doubted in his mind and heart, earth-shaking Poseidon raised a great wave, gloomy and grievous, and with arching crest, and launched it on him. And as a gusty wind tosses a heap of grain when it is dry, and some it scatters one way, some another, so were the long beams scattered. But Odysseus mounting a beam, as if he rode a steed, stripped off the clothing which divine Calypso gave, spread quickly the veil underneath his breast, and plunged down headlong in the sea, with hands outstretched, ready to swim. The great Earth-shaker spied him, and shaking his head he muttered to his heart:

“Thus, after meeting many ills, be tossed about the sea until you join a people who are favorites of Zeus; but even then, I trust, you will not laugh at danger.”

Saying this, he lashed his full-maned horses and came to Aegae, where his lordly dwelling stands.

And now Athene, daughter of Zeus, formed a fresh project. She barred the pathway of the other winds, bade them to cease and all be laid to rest; but she roused bustling Boreas and before it broke the waves, that safely among the oar-loving Phaeacians might come high-born Odysseus, freed from death and doom.

Then two nights and two days on the resistless waves he drifted; many a time his heart faced death. But when the fair-haired dawn brought the third day, then the wind ceased; there came a breathless calm; and close at hand he spied the coast, as he cast a keen glance forward, upborne on a great wave. As when the precious life is watched by children in a father, who lies in sickness, suffering great pain and slowly wasting,—for a hostile power assails him,—and then the one thus prized the gods set free from danger; so precious in Odysseus’ eyes appeared the land and trees. Onward he swam, impatient for his feet to touch the ground. But when he was as far away as one can call, he heard a pounding of the ocean on the ledges; for the great waves roared as on the barren land they madly dashed, and all was whirled in spray. There was no harbor here to hold a ship, no open roadstead; only projecting bluffs, ledges, and reefs. At this Odysseus’ knees grew feeble, and his very soul, and in dismay he said to his stout heart:

“Alas! when Zeus now lets me see unlooked-for land, and forcing my way along the gulf I finally reach its end, no landing anywhere appears out of the foaming sea. Outside are jagged reefs; around thunder the surging waves, and smooth and steep rises the rocky shore. To the edge the sea is deep, and impossible it is to get a footing with both feet and so escape from harm. If I should try to land, great sweeping waves might dash me on the solid rock; useless would the attempt be! But if I swim still farther, hoping to find a sloping shore and harbors off the sea, I fear a sweeping storm may bear me yet again along the swarming sea, loudly lamenting; or God may send upon me a monster of the deep,—and many such great Amphitrite breeds,—for I know how angry is the great Land-shaker.”

While he thus doubted in his mind and heart, a huge wave bore him onward toward the rugged shore. There would his skin have been stripped off and his bones broken, had not the goddess, clear-eyed Athene, given him counsel. Struggling, he grasped the rock with both his hands and clung there, groaning, till the great wave passed. That one he thus escaped, but the back-flowing water struck him again, still struggling, and swept him out to sea. And just as, when a polyp is torn from out its bed, about its suckers clustering pebbles cling, so on the rocks pieces of skin were stripped from his strong hands. The great wave covered him. Then miserably, before his time, Odysseus would have died, if clear-eyed Athene had not given him ready thought. Rising beyond the waves which thundered on the coast, he swam along outside, eying the land, in hopes to find a sloping shore and harbors off the sea. But when, as he swam, he reached the mouth of a fair-flowing river, there the ground seemed most fit, clear of all stones and sheltered from the breeze. As he felt the river flowing forth, within his heart he prayed:

“Listen O lord, whoe’er thou art!

24 Thee, long desired, I find, when flying from the sea and from Poseidon’s threats. Respected even of immortal gods is he who comes a fugitive, as I here now come to thy current and thy knees through weary toil. Show pity, lord! I call myself thy suppliant.”

He spoke, and the god straightway stayed the stream and checked the waves, before him made a calm, and brought him safely into the river’s mouth. Both knees hung loose, and both his sturdy arms, for by the brine his power was broken. His body was all swollen, and water gushed in streams from mouth and nostrils. So, breathless and speechless, in a swoon he lay and dire fatigue engulfed him. But when he gained his breath, and in his breast the spirit rallied, then he unbound the veil of the goddess and dropped it in the river running out to sea; and back a great wave bore it down the stream, and Ino soon received it in her friendly hands. But he, retreating from the river, lay down among the rushes and kissed the bounteous earth, and in dismay he said to his stout heart:

“Ah me! What shall I do? What will become of me even now? If by the stream I watch throughout the weary night, may not the bitter frost and the fresh dew together after this swoon end my exhausted life? The breeze from off a river blows cool toward early morning. But if I climb the hill-side up to the dusky wood and sleep in the thick bushes,—supposing that the chill and weariness depart and pleasant sleep come on,—I am afraid I may become the wild beasts’ prey and prize.”

Yet on reflecting thus, this seemed the better way: he hastened therefore to the wood. This he found near the water, with open space around. He crept under a pair of shrubs sprung from a single spot; the one was wild, the other common, olive. These no force of wind with its chill breath could pierce, no sunbeams smite, nor rain pass through, they grew so thickly intertwined with one another. Under them crept Odysseus, and quickly with his hands he scraped a bed together, an ample one, for a thick fall of leaves was there, enough to shelter two or three men in winter-time, however severe the weather. This long-tried royal Odysseus saw with joy, and lay down in the midst, heaping the fallen leaves above. As a man hides a brand in a dark bed of ashes, at some outlying farm where neighbors are not near, hoarding a seed of fire not otherwise to be lighted, even so did Odysseus hide himself in leaves, and on his eyes Athene poured a sleep, quickly to ease him from the fatigue of toil, letting his eyelids close.