BOOK XXI

The Trial of the Bow

And now the goddess, clear-eyed Athene, put in the mind of Icarius’ daughter, heedful Penelope, to offer to the suitors in the hall the bow and the gray steel, as means of sport and harbingers of death. She mounted the long stairway of her house, holding a crooked key in her firm hand,—a goodly key of bronze, having an ivory handle,—and hastened with her slave-maids to a far-off room where her lord’s treasure lay, bronze, gold, and well-wrought steel. Here also lay his curved bow and the quiver for his arrows,—and many grievous shafts were in it still,—gifts which a friend had given Odysseus when he met him once in Lacedaemon, —Iphitus, son of Eurytus, a man like the immortals. At Messene the two met, in the house of wise Orsilochus. Odysseus had come hither to claim a debt which the whole district owed him; for upon ships of many oars Messenians carried off from Ithaca three hundred sheep together with their herdsmen. In the long quest for these, Odysseus took the journey when he was but a youth; for his father and the other elders sent him forth. Iphitus, on the other hand, was seeking horses; for twelve mares had been lost, which had as foals twelve hardy mules. These afterwards became the death and doom of Iphitus when he met the stalwart son of Zeus, the hero Hercules, who well knew deeds of daring; for Hercules slew Iphitus in his own house, although his guest, and recklessly did not regard the anger of the gods nor yet the proffered table, but slew the man and kept at his own hall the strong-hoofed mares. It was when seeking these that Iphitus had met Odysseus and given the bow which in old days great Eurytus was wont to bear, and which on dying in his lofty hall he left his son. To Iphitus, Odysseus gave a sharp-edged sword and a stout spear, as the beginning of a loving friendship. They never sat, however, at one another’s table; ere that could be, the son of Zeus slew godlike Iphitus, the son of Eurytus, who gave the bow. Royal Odysseus when going off to war in the black ships would never take this bow. It always stood in its own place at home, as a memorial of his honored friend. In his own land he bore it.

Now when the royal lady reached this room and stood on the oaken threshold,—which long ago the carpenter had smoothed with skill and leveled to the line, fitting the posts thereto and setting the shining doors,—then quickly from its ring she loosed the strap, thrust in the key, and with a careful aim shot back the door-bolts. As a bull roars when feeding in the field, so roared the goodly door touched by the key and open flew before her. She stepped to a raised dais where stood some chests in which lay fragrant garments. Thence reaching up, she took from its peg the bow in the glittering case which held it. And now she sat down and laid the case upon her lap and loudly weeping drew her lord’s bow forth. But when she had had her fill of tears and sighs, she hastened to the hall to meet the lordly suitors, bearing in hand the curved bow and the quiver for the arrows, and many grievous shafts were in it still. Beside her, slave-maids bore a box in which lay many a piece of steel and bronze, implements of her lord’s for games like these. And when the royal lady reached the suitors, she stood beside a column of the strong-built roof, holding before her face her delicate veil, the while a faithful slave-maid stood upon either hand. And straightway she addressed the suitors, speaking thus:

“Listen, you haughty suitors who beset this house, eating and drinking ever, now my husband is long gone; no word of excuse can you suggest except your wish to marry me and win me for your wife. Well then, my suitors,—since before you stands your prize,—I offer you the mighty bow of prince Odysseus; and whoever with his hands shall lightliest bend the bow and shoot through all twelve axes, him I will follow and forsake this home, this bridal home, so very beautiful and full of wealth, a place I think I ever shall remember, even in my dreams.”

37So saying, she bade Eumaeus, the noble swineherd, deliver to the suitors the bow and the gray steel. With tears Eumaeus took the arms and laid them down before them. Near by, the cowherd also wept to see his master’s bow. But Antinouäs rebuked them, and spoke to them and said:

“You stupid boors, who only mind the passing minute, wretched pair, what do you mean by shedding tears, troubling this lady’s heart, when already her heart is prostrated with grief at losing her dear husband? Sit down and eat in silence, or else go forth and weep, but leave the bow behind, a dread ordeal for the suitors; for I am sure this polished bow will not be bent with ease. There is not a man of all now here so powerful as Odysseus. I saw him once myself and well recall him, though I was then a child.”

He spoke, but in his breast his heart was hoping to draw the string and send an arrow through the steel; yet he was to be the first to taste the shaft of good Odysseus, whom he now wronged though seated in his hall, while to like outrage he encouraged all his comrades. To these now spoke revered Telemachus:

“Ha! Zeus the son of Kronos has made me play the fool! My mother,—and wise she is,—says she will follow some strange man and quit this house; and I but laugh and in my silly soul am glad. Come then, you suitors, since before you stands your prize, a lady whose like cannot be found throughout Achaean land, in sacred Pylos, Argos, or Mycenae, in Ithaca itself, or the dark mainland, as you yourselves well know,—what needs my mother praise?—come then, delay not with excuse nor longer hesitate to bend the bow, but let us learn what is to be. I too might try the bow. And if I stretch it and send an arrow through the steel, then with no shame to me my honored mother may forsake this house and follow some one else, leaving me here behind; for I shall then be able to wield my father’s arms.”

He spoke, and flung his red cloak from his neck, rising full height, and put away the sharp sword also from his shoulder. First then he set the axes, marking one long furrow for them all, aligned by cord. The earth on the two sides he stamped down flat. Surprise filled all beholders to see how properly he set them, though he had never seen the game before. Then he went and stood upon the threshold and began to try the bow. Three times he made it tremble as he sought to make it bend. Three times he slacked his strain, still hoping in his heart to draw the string and send an arrow through the steel. And now he might have drawn it by force of a fourth tug, had not Odysseus shook his head and stopped the eager boy. So to the suitors once more spoke revered Telemachus:

“Ah! Shall I ever be a coward and a weakling, or am I still but young and cannot trust my arm to right me with the man who wrongs me first? But come, you who are stronger men than I, come try the bow and end the contest.”

So saying, he laid by the bow and stood it on the ground, leaning it on the firm-set polished door. The swift shaft, too, he likewise leaned against the bow’s fair knob, and once more took the seat from which he first arose. Then said to them Antinouäs, Eupeithes’ son:

“Rise up in order all, from left to right, beginning where the cupbearer begins to pour the wine.”

So said Antinouäs, and his saying pleased them. Then first arose Leiodes, son of Oenops, who was their soothsayer and had his place beside the goodly mixer, farthest along the hall. To him alone their lawlessness was hateful; he abhorred the suitor crowd. He it was now who first took up the bow and the swift shaft; and going to the threshold, he stood and tried the bow. He could not bend it. Tugging the string made sore his hands, his soft, unhorny hands; and to the suitors thus he spoke:

“No, friends, I cannot bend it. Let some other take the bow. Ah, many chiefs this bow shall rob of life and breath! Yet better far to die than live and still to fail in that for which we constantly are gathered, waiting expectantly from day to day! Now each man hopes and purposes at heart to win Penelope, Odysseus’ wife. But when he shall have tried the bow and seen his failure, then to some other fair-robed woman of Achaea let each go, and offer her his suit and court her with his gifts. So may Penelope marry the man who gives her most and comes with fate to favor!”

When he had spoken, he laid by the bow, leaning it on the firm-set polished door. The swift shaft, too, he likewise leaned against the bow’s fair knob, and once more took the seat from which he first arose. But Antinouäs rebuked him, and spoke to him, and said:

“Leiodes, what words have passed the barrier of your teeth? Strange words and harsh! Disturbing words to hear! As if this bow must rob our chiefs of life and breath because you cannot bend it! Why, your good mother did not bear you for a brandisher of bows and arrows. But others among the lordly suitors will bend it by and by.”

So saying, he gave an order to Melanthius, the goatherd: “Hasten, Melanthius, and light a fire in the hall and set a long bench near, with fleeces on it; then bring me the large cake of fat which lies inside the door, that after we have warmed the bow and greased it well, we young men try it and so end the contest.”

He spoke, and straightway Melanthius kindled a steady fire, and set a bench beside it with a fleece thereon, and brought out the large cake of fat which lay inside the door, and so the young men warmed the bow and made their trial. But yet they could not bend it; they fell far short of power. Antinouäs, however, still held back, and prince Eurymachus, who were the suitors’ leaders; for they in manly excellence were quite the best of all.

Meanwhile out of the house at the same moment came two men, princely Odysseus’ herdsmen of the oxen and the swine; and after them came royal Odysseus also. And when they were outside the gate, beyond the yard, speaking in gentle words Odysseus said:

“Cowherd, and you too, swineherd, may I tell a certain tale, or shall I hide it still? My heart bids speak. How ready would you be to aid Odysseus if he should come from somewhere, thus, on a sudden, and a god should bring him home? Would you support the suitors or Odysseus? Speak freely, as your heart and spirit bid you speak.”

Then said to him the herdsman of the cattle: “O father Zeus, grant this my prayer! May he return and Heaven be his guide! Then shall you know what might is mine and how my hands obey.”

So prayed Eumaeus too to all the gods, that wise Odysseus might return to his own home. So when he knew with certainty the heart of each, finding his words once more Odysseus said:

“Lo, it is I, through many grievous toils now in the twentieth year come to my native land! And yet I know that of my servants none but you desires my coming. From all the rest I have not heard one prayer that I return. To you then I will truly tell what shall hereafter be. If God by me subdues the lordly suitors, I will obtain you wives and give you wealth and homes established near my own; and henceforth in my eyes you shall be friends and brethren of Telemachus. Come then and I will show you too a very trusty sign,—that you may know me certainly and be assured in heart,—the scar the boar dealt long ago with his white tusk, when I once journeyed to Parnassus with Autolycus’ sons.”

So saying, he drew aside his rags from the great scar. And when the two beheld and understood it all, their tears burst forth; they threw their arms round wise Odysseus and passionately kissed his face and neck. So likewise did Odysseus kiss their heads and hands. And daylight had gone down upon their weeping had not Odysseus stayed their tears and said:

“Have done with grief and wailing, or someone coming from the hall may see, and tell the tale indoors. So, go in one by one, not all together. I will go first, you after. And let this be agreed: the rest within, the lordly suitors, will not allow me to receive the bow and quiver. But, noble Eumaeus, bring the bow along the room and lay it in my hands. Then tell the women to lock the hall’s close-fitting doors; and if from their inner room they hear a moaning or a strife within our walls, let no one venture forth, but stay in silence at her work. And, noble Philoetius, in your care I put the court-yard gates. Bolt with the bar and quickly lash the fastening.”

So saying, Odysseus made his way into the stately house, and went and took the seat from which he first arose. And soon the serving-men of princely Odysseus entered too.

Now Eurymachus held the bow and turned it up and down, trying to heat it at the glowing fire. But still, with all his pains, he could not bend it; his proud soul groaned aloud. Then bitterly he spoke; these were the words he said:

“Ah! here is woe for me and woe for all! Not that I so much mourn missing the marriage, though vexed I am at that. Still, there are enough more women of Achaea, both here in sea-encircled Ithaca and in the other cities. But if in strength we fall so short of princely Odysseus that we cannot bend his bow—oh, the disgrace for future times to hear!”

Then said Antinouäs, Eupeithes’ son: “Not so, Eurymachus, and you yourself know better. Today throughout the land is the archer-god’s high feast. Who then could bend a bow? No, quietly lay it by; and for the axes, what if we leave them standing? Nobody, I am sure, will carry one away and trespass on the house of Laeärtes’ son, Odysseus. Come then, and let the wine-pourer give pious portions to our cups, that after a libation we may lay aside curved bows. Tomorrow morning tell Melanthius, the goatherd, to drive us here the choicest goats of all his flock; and we will set the thighs before the archer-god, Apollo, then try the bow and end the contest.”

So said Antinouäs, and his saying pleased them. Pages poured water on their hands; young men brimmed bowls with drink and served to all, with a first pious portion for the cups. And after they had poured and drunk as their hearts would, then in his subtlety said wise Odysseus:

“Listen, you suitors of the illustrious queen, and let me tell you what the heart within me bids. I beg a special favor of Eurymachus, and great Antinouäs too; for his advice was wise, that you now drop the bow and leave the matter with the gods, and in the morning some god shall grant the power to whom he may. But give me now the polished bow, and let me in your presence prove my skill and power and see if I have yet such vigor left as once there was within my supple limbs, or whether wanderings and neglect have ruined all.”

At these his words all were outraged, fearing that he might bend the polished bow. So Antinouäs rebuked him, and spoke to him and said: “You scurvy stranger, with not a whit of sense, are you not satisfied to eat in peace with us, your betters, unstinted in your food and hearing all we say? Nobody else, stranger or beggar, hears our talk. It’s wine that goads you, honeyed wine, a thing that has brought others trouble, when taken greedily and drunk without due measure. Wine crazed the Centaur, famed Eurytion, at the house of bold Peirithouäs, on his visit to the Lapithae.

38 And when his wits were crazed with wine, he madly wrought foul outrage on the household of Peirithouäs. So indignation seized the heroes. Through the porch and out of doors they rushed, dragging Eurytion forth, shorn by the pitiless sword of ears and nose. Crazed in his wits, he went his way, bearing in his bewildered heart the burden of his guilt. And hence arose a feud between the Centaurs and mankind; but the beginning of the woe he himself caused by wine. Even so I prophesy great harm to you, if you shall bend the bow. No kindness will you meet from any in our land, but we will send you by black ship straight to king Echetus, the bane of all mankind, out of whose hands you never shall come clear. Be quiet, then, and take your drink! Do not presume to vie with younger men!”

Then said to him heedful Penelope: “Antinouäs, it is neither honorable nor fitting to worry strangers who may reach this palace of Telemachus. Do you suppose the stranger, if he bends the great bow of Odysseus, confident in his skill and strength of arm, will lead me home and take me for his wife? He in his inmost soul imagines no such thing. Let none of you sit at the table disturbed by such a thought; for that could never, never, be!”

Then answered her Eurymachus, the son of Polybus: “Daughter of Icarius, heedful Penelope, we do not think the man will marry you. Of course that could not be. And yet we dread the talk of men and women, and fear lest one of the baser sort of the Achaeans say: ‘Men far inferior sue for a good man’s wife, and cannot bend his polished bow. But someone else,—a wandering beggar,—came, and easily bent the bow and sent an arrow through the steel. This they will say, to us a shame indeed.”

Then said to him heedful Penelope: “Eurymachus, men cannot be in honor in the land and rudely rob the household of their prince. Why then count this a shame? The stranger is truly tall, and well-knit too, and calls himself the son of a good father. Give him the polished bow, and let us see. For this I tell you, and it shall be done; if he shall bend it and Apollo grants his prayer, I will clothe him in a coat and tunic, goodly garments, give him a pointed spear to keep off dogs and men, a two-edged sword, and sandals for his feet, and I will send him where his heart and soul may bid him go.”

Then answered her discreet Telemachus: “My mother, no Achaean has better right than I to give or to refuse the bow to any as I will. And out of all who rule in rocky Ithaca, or in the islands off toward grazing Elis, none may oppose my will, even though I wished to put these bows into the stranger’s hands and let him take them once for all away. Then seek your chamber and attend to matters of your own,—the loom, the distaff,—and bid the women ply their tasks. Bows are for men, for all, especially for me; for power within this house rests here.”

Amazed, she turned to her own room again, for the wise saying of her son she laid to heart. And coming to the upper chamber with her maids, she there bewailed Odysseus, her dear husband, till on her lids clear-eyed Athene caused a sweet sleep to fall.

Meanwhile the noble swineherd, taking the curved bow, was bearing it away. But the suitors all broke into uproar in the hall, and a rude youth would say: “Where are you carrying the curved bow forth, you miserable swineherd? Crazy fool! Soon out among the swine, away from men, swift dogs shall eat you,—dogs you yourself have bred,—will but Apollo and the other deathless gods be gracious!”

At these their words the bearer of the bow laid it down where he stood, frightened because the crowd within the hall cried out upon him. But from the other side Telemachus called threateningly aloud: “Nay, father! Carry on the bow! You cannot well heed all. Take care, or I, a nimbler man than you, will drive you to the fields with pelting stones. Superior in strength I am to you. Ah, would I were as much beyond the others in the house, beyond these suitors, in my skill and strength of arm! Then would I soon send somebody away in sorrow from my house; for men work evil here.”

He spoke, and all burst into merry laughter and laid aside their bitter anger with Telemachus. And so the swineherd, bearing the bow along the hall, drew near to wise Odysseus and put it in his hands; then calling aside nurse Eurycleia, thus he said:

“Telemachus bids you, heedful Eurycleia, to lock the hall’s close-fitting doors; and if a woman from the inner room hears moaning or a strife within our walls, let her not venture forth, but stay in silence at her work.”

Such were his words; unwinged, they rested with her. She locked the doors of the stately hall. Then silently from the house Philoetius stole forth and at once barred the gates of the fenced court. Beneath the portico there lay a curved ship’s cable, made of byblus plant.

ba With this he lashed the gates, then passed indoors himself, and went and took the seat from which he first arose, eyeing Odysseus. Now Odysseus already held the bow and turned it round and round, trying it here and there to see if worms had gnawed the horn while its lord was far away. And glancing at his neighbor one would say:

“A sort of expert or con-man with the bow this fellow is. No doubt at home he has himself a bow like that, or means to make one like it. See how he turns it in his hands this way and that, ready for mischief,—rascal!”

Then would another rude youth answer thus: “Oh may he always meet such luck as when he is unable now to bend the bow!”

So talked the suitors. Meantime wise Odysseus, when he had handled the great bow and scanned it closely,—even as one well-skilled to play the lyre and sing stretches with ease round its new peg a cord, securing at each end the twisted sheep-gut; so without effort did Odysseus string the mighty bow. Holding it now with his right hand, he tried its cord; and clear to the touch it sang, voiced like the swallow. Great consternation came upon the suitors. All faces then changed color. Zeus thundered loud for signal. And glad was long-tried royal Odysseus to think the son of crafty Kronos sent an omen. He picked up a swift shaft which lay beside him on the table, drawn. Within the hollow quiver still remained the rest, which the Achaeans soon should prove. Then laying the arrow on the arch, he drew the string and arrow notches, and forth from the bench on which he sat let fly the shaft, with careful aim, and did not miss an axe’s ring from first to last, but clean through all sped on the bronze-tipped arrow; and to Telemachus he said:

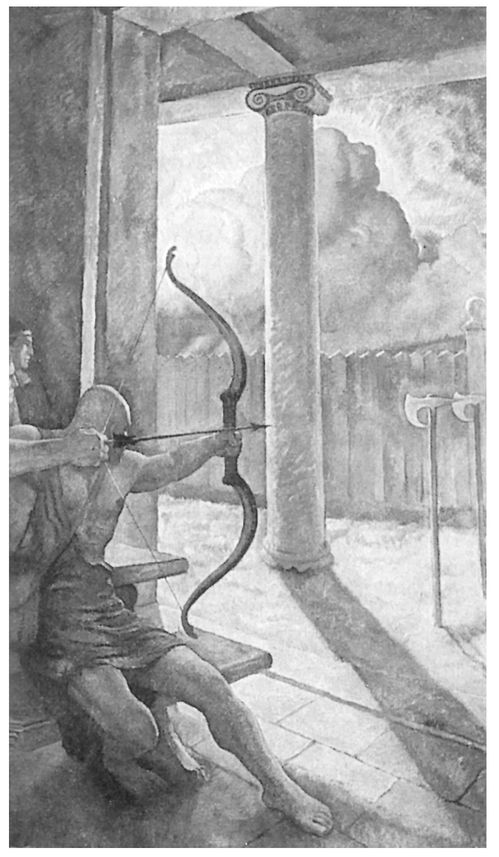

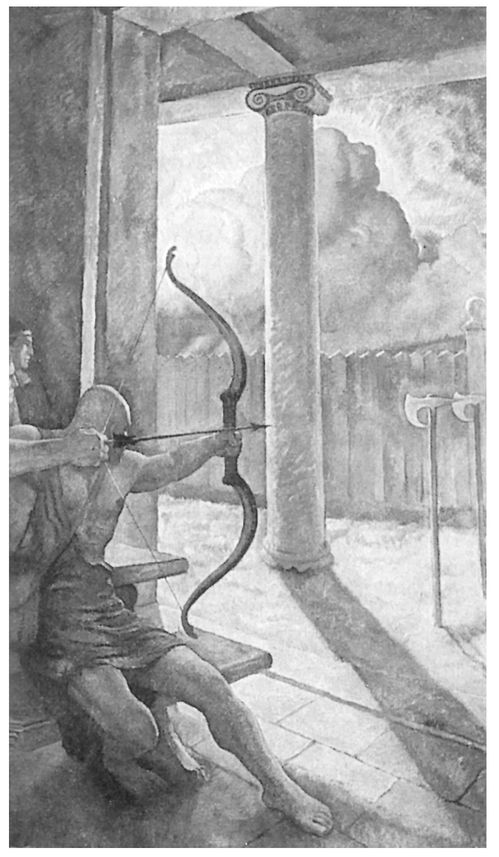

The Trial of the Bow—from a painting by N.C. Wyeth

“Telemachus, the guest now sitting in your hall brings you no shame. I did not miss my mark, nor in the bending of the bow make a long labor. My strength is sound as ever, not what the mocking suitors here despised. But it is time for the Achaeans to make supper ready, while it is daylight still; and then for us in other ways to make them sport,—with dance and lyre; for these attend a feast.”

He spoke and frowned the sign. His sharp sword then Telemachus girt on, the son of princely Odysseus; clasped his right hand around his spear, and close beside his father’s seat he took his stand, armed with the gleaming bronze.