CHAPTER 2

Corporate and Municipal Debt Securities

Corporate Bonds

Corporations will issue bonds in an effort to raise working capital to build and expand their business. Corporate bondholders are not owners of the corporation; they are creditors of the company. Corporate debt financing is known as leverage financing because the company pays interest only on the loan until maturity. Bondholders do not have voting rights as long as the company pays the interest and principal payments in a timely fashion. If the company defaults, the bondholders may be able to use their position as creditors to gain a voice in the company's management. Bondholders will always be paid before preferred and common stockholders in the event of liquidation. Interest income received by investors on corporate bonds is taxable at all levels, federal, state, and local.

Types of Bond Issuance

Bearer Bonds

Bonds that are issued in coupon or bearer form do not record the owner's information with the issuer and the bond certificate does not have the legal owner's name printed on it. As a result, anyone who possesses the bond is entitled to receive the interest payments by clipping the coupons attached to the bond and depositing them in a bank or trust company for payment. Additionally, the bearer is entitled to receive the principal payment at the bond's maturity. Bearer bonds are no longer issued within the United States; however, they are still issued outside the country.

Registered Bonds

Most bonds now are issued in registered form. Bonds that have been issued in registered form have the owner's name recorded on the books of the issuer and the buyer's name will appear on the bond certificate.

Principal-Only Registration

Bonds that have been registered as to principal only have the owner's name printed on the bond certificate. The issuer knows who owns the bond and who is entitled to receive the principal payment at maturity. However, the bondholder will still be required to clip the coupons to receive the semiannual interest payments.

Fully Registered

Bonds that have been issued in fully registered form have the owner's name recorded for both the interest and principal payments. The owner is not required to clip coupons and the issuer will send out the interest payments directly to the holder on a semiannual basis. The issuer will also send the principal payment along with last semiannual interest payment directly to the owner at maturity. Most bonds in the United States are issued in fully registered form.

Book Entry/Journal Entry

Bonds that have been issued in book entry or journal entry form have no physical certificate issued to the holder as evidence of ownership. The bonds are fully registered and the issuer knows who is entitled to receive the semiannual interest payments and the principal payment at maturity. The investor's only evidence of ownership is the trade confirmation, which is generated by the brokerage firm, when the purchase order has been executed.

Bond Certificate

If a bond certificate is issued, it must include:

- Name of issuer

- Principal amount

- Issuing date

- Maturity date

- Interest payment dates

- Place where interest is payable (paying agent)

- Type of bond

- Interest rate

- Call feature (if any or noncallable)

- Reference to the trust indenture

Bond Pricing

Once issued, corporate bonds trade in the secondary market between investors similar to the way equity securities do. The price of bonds in the secondary market depends on all of the following:

- Rating

- Interest rates

- Term

- Coupon rate

- Type of bond

- Issuer

- Supply and demand

- Other features, i.e., callable, convertible

Corporate bonds are always priced as a percentage of par and par value for all bonds is always $1,000, unless otherwise stated.

Par Value

Par value of a bond is equal to the amount that the investor has loaned to the issuer. The terms par value, face value, and principal amount are synonymous and are always equal to $1,000. The principal amount is the amount that will be received by the investor at maturity, regardless of the price the investor paid for the bond. An investor who purchases a bond in the secondary market for $1,000 is said to have paid par for the bond.

Discount

In the secondary market, many different factors affect the price of the bond. It is not at all unusual for an investor to purchase a bond at a price that is below the bond's par value. Anytime an investor buys a bond at a price that is below the par value, they are said to be buying the bond at a discount.

Premium

Often market conditions will cause the price of existing bonds to rise and make it attractive for the investors to purchase a bond at a price that is greater than its par value. Anytime an investor buys a bond at a price that exceeds its par value, the investor is said to have paid a premium.

Corporate Bond Pricing

All corporate bonds are priced as a percentage of par into fractions of a percent. For example, a quote for a corporate bond reading 95 actually translates into:

A quote for a corporate bond of 97¼ translates into:

Bond Yields

A bond's yield is the investor's return for holding the bond. Many factors affect the yield that an investor will receive from a bond such as:

- Current interest rates

- Term of the bond

- Credit quality of the issuer

- Type of collateral

- Convertible or callable

- Purchase price

An investor who is considering investing in a bond needs to be familiar with the bond's nominal yield, current yield, and yield to maturity.

Nominal Yield

A bond's nominal yield is the interest rate that is printed or “named” on the bond. The nominal yield is always stated as a percentage of par. It is fixed at the time of the bond's issuance and never changes. The nominal yield may also be called the coupon rate. For example, a corporate bond with a coupon rate of 8% will pay the holder $80.00 per year in interest.

Current Yield

The current yield is a relationship between the annual interest generated by the bond and the bond's current market price. To find any investment's current yield, use the following formula:

For example, let's take the same 8% corporate bond used in the previous example on nominal yield and see what its current yield would be if we paid $1,100 for the bond.

In this example, we have purchased the bond at a premium or a price that is higher than par and we see that the current yield on the bond is lower than the nominal yield.

Let's take a look at the current yield on the same bond if we were to purchase the bond at a discount or a price which is lower than par. Let's see what the current yield for the bond would be if we pay $900 for the bond.

In this example we see that the current yield is higher than the nominal yield. By showing examples calculating the current yield for the same bond purchased at both a premium and a discount, we have demonstrated the inverse relationship between prices and yields. That is to say, prices and yields on income-producing investments move in the opposite direction. As the price of an investment rises, the investment's yield falls. Conversely, as the price of the investment falls, the investment's yield will rise.

Yield to Maturity

A bond's yield to maturity is the investor's total annualized return for investing in the bond. A bond's yield to maturity takes into consideration the annual income received by the investor along with any difference between the price the investor paid for the bond and the par value that will be received at maturity. It also assumes that the investor is reinvesting the semiannual interest payments at the same rate. The yield to maturity is the most important yield for an investor who purchases the bond.

Yield to Maturity: Premium Bond

The yield to maturity for a bond purchased at a premium will be the lowest of all the investor's yields. Although an investor may purchase a bond at a price that exceeds the par value of the bond, the issuer is only obligated to pay the bondholder the par value upon maturity. For example: An investor who purchases a bond at 110 or for $1,100 will receive only $1,000 at maturity and, therefore, will lose the difference of $100. This loss is what causes the yield to maturity to be the lowest of the three yields for an investor who purchases a bond at a premium.

Yield to Maturity: Discount Bond

The yield to maturity for a bond purchased at a discount will be the highest of all of the investor's yields. In this case, the investor has purchased the bond at a price that is less than the par value of the bond. In this example, even though the investor paid less than the par value for the bond, the issuer is still obligated to pay them the full par value of the bond at maturity or the full $1,000. For example: An investor who purchases a bond at 90 or for $900 will still be entitled to receive the full par amount of $1,000 at maturity, therefore, gaining $100. This gain is what causes the yield to maturity to be the highest of the three yields for an investor who purchases a bond at a discount.

Calculating the Yield to Maturity

When an investor purchases a bond in the secondary market at a discount, the discount must be accreted over the remaining life of the bond. The accretion of the discount will result in a higher yield to maturity. When an investor purchases a bond in the secondary market at a premium, the premium must be amortized over the remaining life of the bond. The amortization of the premium will result in a lower yield to maturity.

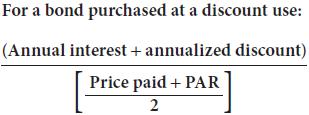

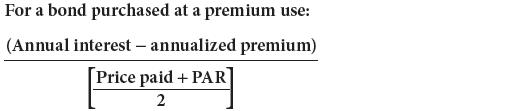

In order to calculate the bonds approximate yield to maturity, use the following formulas:

The annualized discount is found by taking the total discount and dividing it by the number of years remaining until maturity. For example, let's assume an investor purchased a 10% bond at $900 with 10 years until maturity. The bonds approximate yield to maturity would be found as follows:

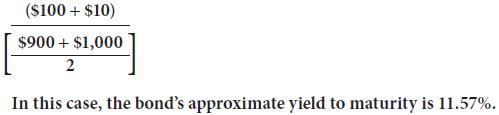

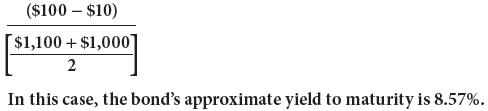

The annualized premium is found by taking the total premium and dividing it by the number of years remaining until maturity. For example, let's assume an investor purchased a 10% bond at $1,100 with 10 years until maturity.

The bond's approximate yield to maturity would be found as follows:

Calculating the Yield to Call

In the event that the bond may be called in or redeemed by the issuer under a call feature, an investor may calculate the approximate yield to call by using the approximate number of years left until the bond may be called.

Realized Compound Yield Returns

Portfolio managers can determine how changing interest rates will affect a bond's yield to maturity by calculating its realized compound yield. A bond's realized compound yield measures a bond's annual return based on the semiannual compounding of coupon payments. The bond's realized compound yield will largely depend on the purchase price of the bond and the rate at which the interest payments are reinvested. Investors with longer holding periods will have higher total dollar and percentage returns.

Yield Spreads

Investors must look at the competing yields that are offered by a wide variety of bonds. The difference in the yields offered by two bonds is known as the yield spread. Many bonds are measured by the relationship between the bond's yield and the yield offered by similar term Treasury securities. This is known as the spread over Treasuries. As perceptions about the issuer and the economy change, yield spreads will change. During times of uncertainty, investors will be less likely to hold more risky debt securities. As a result, the yield spread between Treasuries and more risky corporate debt will widen. An increase in the spread can be seen as an indication that the economy is going to go into a recession and that the issuers of lower quality debt will likely default. Alternatively, a decrease in the spread will be seen as a predictor of an improving economy.

The Real Interest Rate

Investors must calculate the effect inflation will have on the interest they receive on fixed-income securities. The interest rate received by an investor, before the effects of inflation are considered, is known as the nominal interest rate. The real interest rate is what the investor will receive after inflation is factored in. For example, if an investor is receiving an 8% interest rate on a corporate bond when inflation is running at 2%, the investor's real interest rate would be 6%. The investor's nominal interest rate consists of the real interest rate plus an inflation premium. The inflation premium factors in the expected rate of inflation during various bond maturities.

Bond Maturities

When a bond matures, the principal payment and the last semiannual interest payment are due. Corporations will select to issue bonds with the maturity type that best fits their needs, based on the interest rate environment and marketability.

Term Maturity

A term bond is the most common type of corporate bond issue. With a term bond, the entire principal amount becomes due on a specific date. For example, if XYZ corporation issued $100,000,000 worth of 8% bonds due June 1, 2025, the entire $100,000,000 would be due to bondholders on June 1, 2025. On June 1, bondholders would also receive their last semiannual interest payment and their principal payment.

Serial Maturity

A serial bond issue is one that has a portion of the issue maturing over a series of years. Traditionally, serial bonds have larger portions of the principal maturing in later years. The portion of the bonds maturing in later years will carry a higher yield to maturity because investors who have their money at risk longer will demand a higher interest rate.

Balloon Maturity

A balloon issue contains a maturity schedule that repays a portion of the issue's principal over a number of years, just like a serial issue. However, with a balloon maturity, the largest portion of the principal amount is due on the last date.

Series Issue

With a series issue, corporations may elect to spread the issuance of the bonds over a period of several years. This will give the corporation the flexibility to borrow money to meet its goals as its needs change.

Types of Corporate Bonds

A corporation will issue or sell bonds as a means to borrow money to help the organization meet its goals. Corporate bonds are divided into two main categories: secured and unsecured.

Secured Bonds

A secured bond is one that is backed by a specific pledge of assets. The assets that have been pledged become known as collateral for the bond issue or the loan. A trustee will hold the title to the collateral and, in the event of default, the bondholders may claim the assets that have been pledged. The trustee then will attempt to sell off the assets in an effort to pay off the bondholders.

Mortgage Bonds

A mortgage bond is a bond that has been backed by a pledge of real property. The corporation will issue bonds to investors and the corporation will pledge real estate, owned by the company, as collateral. A mortgage bond works in a similar fashion to a residential mortgage. In the event of default, the bondholders take the property.

Equipment Trust Certificates

An equipment trust certificate is backed by a pledge of large equipment that the corporation owns. Airlines, railroads, and large shipping companies often will borrow money to purchase the equipment that they need through the sale of equipment trust certificates. Airplanes, railroad cars, and ships are all good examples of the types of assets that might be pledged as collateral. In the event of default, the equipment will be liquidated by the trustee in an effort to pay off the bondholders.

Collateral Trust Certificates

A collateral trust certificate is a bond that has been backed by a pledge of securities that the issuer has purchased for investment purposes or they could be backed by shares of a wholly owned subsidiary. Both stocks and bonds are acceptable forms of collateral as long as another issuer has issued them. Securities that have been pledged as collateral are generally required to be held by the trustee for safekeeping. In the event of a default, the trustee will attempt to liquidate the securities, which have been pledged as collateral, and divide the proceeds among the bondholders.

It's important to note that while having a specific claim against an asset that has been pledged as collateral benefits the bondholder, bondholders do not want to take title to the collateral. Bondholders invest for the semiannual interest payments and the return of their principal at maturity.

Unsecured Bonds

Unsecured bonds are known as debentures and have no specific asset pledged as collateral for the loan. Debentures are only backed by the good faith and credit of the issuer. In the event of a default, the holder of a debenture is treated like a general creditor.

Subordinated Debentures

A subordinated debenture is an unsecured loan to the issuer that has a junior claim on the issuer in the event of default relative to the straight debenture. Should the issuer default, the holders of the debentures and other general creditors will be paid before the holders of the subordinate debentures will be paid anything.

Income/Adjustment Bonds

Corporations, usually in severe financial difficulty, issue income or adjustment bonds. The bond is unsecured and the investor is only promised to be paid interest if the corporation has enough income to do so. As a result of the large risk that the investor is taking, the interest rate is very high and the bonds are issued at a deep discount to par. An income bond is never an appropriate recommendation for an investor seeking income or safety of principal.

Zero-Coupon Bonds

A zero-coupon bond is a bond that pays no semiannual interest. It is issued at a deep discount from the par value and appreciates up to par at maturity. This appreciation represents the investor's interest for purchasing the bond. Corporations, the U.S. government, and municipalities will all issue zero-coupon bonds in an effort to finance their activities. An investor might be able to purchase the $1,000 principal payment in 20 years for as little as $300 today. Because zero-coupon bonds pay no semiannual interest and the price is so deeply discounted from par, the price of the bond will be the most sensitive to a change in the interest rates. Both corporate and U.S. government zero-coupon bonds subject the investor to federal income taxes on the annual appreciation of the bond. This is known as phantom income.

Guaranteed Bonds

A guaranteed bond is a bond whose interest and principal payments are guaranteed by a third party such as a parent company. The higher the credit rating of the company who is guaranteeing the bonds the better the guarantee.

Convertible Bonds

A convertible bond is a corporate bond that may be converted or exchanged for common shares of the corporation at a predetermined price known as the conversion price. Convertible bonds have benefits to both the issuer and the investor. Because the bond is convertible, it usually will pay a lower rate of interest than nonconvertible bonds. This lower interest rate can save the corporation an enormous amount of money in interest expense over the life of the issue. The convertible feature will also benefit the investor if the common stock does well. If the shares of the underlying common stock appreciate, the investor could realize significant capital appreciation in the price of the bond and may also elect to convert the bond into common stock in the hopes of realizing additional appreciation. As an investor in the bond, they maintain a senior position as a creditor while enjoying the potential for capital appreciation.

Converting Bonds into Common Stock

All Series 65 candidates must be able to perform the conversion calculations for both convertible bonds and preferred stock. It is essential that prospective representatives are able to determine the following:

Number of shares: To determine the number of shares that can be received upon conversion, use the following formula:

Parity Price

A stock's parity price determines the value at which the stock must be priced in order for the value of the common stock to be equal to the value of the bond that the investor already owns. The value of the stock that can be received by the investor upon conversion must be equal to, or at parity with, the value of the bond. Otherwise, converting the bonds into common stock would not make economic sense. Determining parity price is a two-step process. First, one must determine the number of shares that can be received by using the formula: par value/conversion price. Then it is necessary to calculate the price of each share at the parity price.

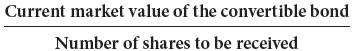

To determine parity price, use the following formula:

In this example, the convertible bond was quoted at 120, which equals a dollar price of $1,200. We determined that the investor could receive 40 shares of stock for each bond so the parity price equals:

If the question is looking for the number of shares or the parity price for a convertible preferred stock, the formulas are the same and the only thing that changes is the par value. Par value for all preferred stocks is $100 instead of $1,000 par value for bonds.

Advantages of Issuing Convertible Bonds

Only corporations may issue convertible bonds. Some of the advantages of issuing convertible bonds to the company are:

- Makes the issue more marketable

- Can offer a lower interest rate

- If the bonds are converted, the debt obligation is eliminated.

- The issuance of the convertible bonds does not immediately dilute ownership or earnings per share.

Disadvantages of Issuing Convertible Bonds

There are some disadvantages to issuing convertible bonds for the company such as:

- Reduced leverage upon conversion

- Conversion causes the loss of tax-deductible interest payments

- Conversion dilutes shareholder's equity

- Conversion by a large holder may shift control of the company

Convertible Bonds and Stock Splits

If a corporation declares a stock split or a stock dividend, the conversion price of the bond will be adjusted accordingly. The trust indenture of a convertible bond will state the maximum number of shares that the corporation may issue while the bonds are outstanding, as well as the minimum price at which the additional shares may be issued.

The Trust Indenture Act of 1939

The Trust Indenture Act of 1939 requires that corporate bond issues in excess of $5,000,000, that are to be repaid during a term in excess of one year, issue a trust indenture for the issue. The trust indenture is a contract between the issuer and the trustee. The trustee acts on behalf of all of the bondholders and ensures that the issuer is in compliance with all of the promises and covenants made to the bondholders. The trustee is appointed by the corporation and is usually a bank or a trust company. The Trust Indenture Act of 1939 only applies to corporate issuers. Both federal and municipal issuers are exempt.

Bond Indenture

Corporate bonds may be issued with either an open-end or closed-end indenture. Bonds issued with an open-end indenture allow the corporation to issue additional bonds secured by the same collateral and whose claim on the collateral is equal to the original issue. A closed-end indenture does not allow the corporation to issue additional bonds having an equal claim on the collateral. If the corporation wants to issue new bonds, their claim must be subordinate to the claim of the original issue or secured by other collateral.

Ratings Considerations

When the rating agencies assign a rating to a debt issue, they must look at many factors concerning the issuer's financial condition such as:

- Cash flow

- Total amount and type of debt outstanding

- Ability to meet interest and principal payments

- Collateral

- Industry and economic trends

- Management

S&P and Moody's are the two biggest ratings agencies. In order for a corporation to have their debt rated by one of these agencies, the issuer must request it and pay for the service. One of the main reasons a corporation would want to have their debt rated is because many investors will not purchase bonds that have not been rated. Additionally, if the issuer receives a higher rating, they will be able to sell the bonds with a lower interest rate.

Exchange Traded Notes (ETNs)

Exchange-traded notes sometimes known as equity-linked notes or index-linked notes are debt securities that base a maturity payment on the performance of an underlying security or group of securities such as an index. ETNs do not make coupon or interest payments to investors during the time the investor owns the ETN. ETNs may be purchased and sold at any time during the trading day and may be purchased on margin and sold short. One very important risk factor to consider when evaluating an ETN is the fact that ETNs are unsecured and carry the credit risk of the issuing bank or broker dealer. Similarly, principal protected notes (PPNs), which are structured products that guarantee the return of the investor's principal if the note is held until maturity, carry a principal guarantee that is only as good as the issuer's credit rating and therefore are never 100% guaranteed.

Euro and Yankee Bonds

A Eurobond is a bond issued in domestic currency of the issuer but sold outside of the issuer's country. For example, if Virgin Plc sold bonds to investors in Japan with the principal and interest payable in British pounds, this would be an example of a Eurobond. A Eurobond carries significant currency risk should the value of the foreign currency fall relative to the domestic currency of the purchaser. If the foreign currency fell, the interest and principal payments to be received in the foreign currency would result in the receipt of fewer units of the domestic currency upon conversion. A Eurodollar bond is a bond issued by a foreign issuer denominated in U.S. dollars and sold to investors outside of the U.S. and outside of the issuer's country. Eurodollar bonds are issued in barer form by foreign corporations, federal governments, and municipalities. Eurobonds trade with accrued interest and interest is paid annually.

A Yankee bond is similar to a Eurodollar bond, except, Yankee bonds are dollar denominated bonds issued by a foreign issuer and sold to U.S. investors. If Virgin sold the same bonds to U.S. investors but the bond's interest and principal were denominated in U.S. dollars rather than in British pounds, the bonds would be a Yankee bond. The advantage of a Yankee bond over a Eurobond for U.S. investors is that the Yankee bond does not have any currency risk.

Variable Rate Securities

The two main types of variable rate securities are Auction Rate Securities and Variable Rate Demand Obligations (VRDO). Auction Rate Securities are long-term securities that are traded as short-term securities. The interest rate paid will be reset at regularly scheduled auctions for the securities every 7, 28, or 35 days. Investors who buy or who elect to hold the securities will have the interest rate paid on the securities reset to the clearing rate until the next auction. Should the auction fail due to a lack of demand, investors who were looking to sell the securities may not have immediate access to their funds. VRDOs have the interest rate reset at set intervals daily, weekly, or monthly. The interest rate set on the VRDO is set by the dealer to a rate that will allow the instruments to be priced at par. Investors may elect to put the securities back to the issuer or a third party on the reset date. Variable rate securities may be issued as debt securities or as preferred stock offerings.

Retiring Corporate Bonds

The retirement of a corporation's debt may occur under any of the following methods:

- Redemption

- Refunding

- Prerefunding

- Exercise of a call feature by the company

- Exercise of a put feature by the investor

- Tender offering

- Open market purchases

Redemption

Bonds are redeemed upon maturity and the principal amount is repaid to investors. At maturity, investors also will receive their last semiannual interest payment.

Refunding

Many times corporations will use the sale of new bonds to pay off the principal of their outstanding bonds. Corporations will issue new bonds to refund their maturing bonds or call the outstanding issue in whole or in part under a call feature. This is known as refunding corporate debt. Refunding corporate debt is very similar to refinancing a home mortgage.

Prerefunding

A corporation may seek to take advantage of a low interest rate environment by prerefunding their outstanding bonds prior to being able to retire them under a call feature. The proceeds from the new issue of bonds are placed in an escrow account and invested in government securities. The interest generated in the escrow account is used to pay the debt service of the outstanding or prerefunded issue. The prerefunded issue will be called in by the company on the first call date. Because the prerefunded bonds are now backed by the government securities held in the escrow account, they are automatically rated AAA. Once an issue has been prerefunded (or advance refunded), the issuer's obligations under the indenture are terminated. This is known as defeasance.

Calling in Bonds

Many times corporations will attach a call feature to their bonds that will allow them to call in and retire the bonds, either at their discretion or on a set schedule. The call feature gives the corporation the ability to manage the amount of debt outstanding, as well as the ability to take advantage of favorable interest rate environments. Most bonds are not callable in the first several years after issuance. This is known as call protection. A call feature on a bond benefits the company, not the investor.

Putting Bonds to the Company

As a way to make a bond issue more attractive to investors, a company may attach a put feature or put option on their bonds. Under a put option, the holder of the bonds may tender the bonds to the company for redemption. Some put features will allow the bondholders to put the bonds to the company for redemption if their rating falls to low or if interest rates rise significantly. A put option on a bond benefits the bondholder.

Tender Offers

A company may make a tender offer in an effort to reduce its outstanding debt or as a way to take advantage of low interest rates. Tender offers may be made for both callable and noncallable bonds. Companies usually will offer a premium for the bonds in order to make the offer attractive to bondholders.

Open-Market Purchases

Issuers, in an effort to reduce the amount of their outstanding debt, may simply repurchase the bonds in the marketplace.

Municipal Bonds

State and local governments will issue municipal bonds in order to help local governments meet their financial needs. Most municipal bonds are considered to be almost as safe as Treasury securities issued by the federal government. However, unlike the federal government, from time to time an issuer of municipal securities does default. The degree of safety varies from state to state and from municipality to municipality. Municipal securities may be issued by:

- States

- Territorial possessions of the United States, such as Puerto Rico

- Legally constituted taxing authorities and their agencies

- Public authorities that supervise ports and mass transit

Types of Municipal Bonds

General Obligation Bond

General obligation bonds (also known as GOs) are full faith and credit bonds. The bonds are backed by the full faith and credit of the issuer and by their ability to raise and levy taxes. In essence, tax revenues back the bonds. GOs often will be issued to fund projects that benefit the entire community and the financed projects generally do not produce revenue of any kind. General obligation bonds would be issued, for example, to fund a local park, a new school building, or a new police station. General obligation bonds that have been issued by the state are backed by income and sales taxes while GOs that have been issued by local governments or municipalities are backed by property taxes.

Voter Approval

General obligation bonds are a drain on the tax revenue of the state or municipality that issues them. The amount of general obligation bonds that may be issued must be within certain debt limits and requires voter approval. The maximum amount of general obligation debt that may be issued is known as the statutory debt limit. State and municipal governments may not issue general obligation debt in excess of their statutory limit.

Property Taxes

General obligation bonds issued at the local level are mostly supported by property tax revenue received from property owners. A property owner's taxes are based on the assessed value of the property, not on its actual market value. Towns will periodically send an assessor to inspect properties and determine what the properties' assessed values are.

Overlapping Debt

Taxpayers are subject to the taxing authority of various municipal authorities. Municipal debt that is issued by different municipal authorities that draws revenue from the same base of taxpayers is known as overlapping debt or coterminous debt.

Revenue Bonds

A revenue bond is a municipal bond that has been issued to finance a revenue-producing project such as a toll bridge. The proceeds from the issuance of the bond will construct or repair the facility, and the debt payments will be supported by revenue generated by the facility. Municipal revenue bonds are exempt from the Trust Indenture Act of 1939, but all revenue bonds must have an indenture that spells out the following:

- Rate covenant

- Maintenance covenant

- Additional bond test

- Catastrophe clause

- Call or put features

- Flow of funds

- Outside audit

- Insurance covenant

- Sinking fund

Industrial Development Bonds/Industrial Revenue Bonds

An industrial revenue bond or an industrial development bond is a municipal bond issued for the benefit of a private corporation. The proceeds from the issuance of the bond will go toward building a facility or toward purchasing equipment for the corporation. The facility or equipment then will be leased back to the corporation and the lease payments will support the debt service on the bonds. Interest earned by some high-income earners on industrial development bonds may be subject to the investor's alternative minimum tax. States are limited as to the amount of industrial revenue bonds that may be issued, based on the population of the state.

Lease Rental Bonds

A lease-back arrangement is created when a municipality issues a municipal bond to build a facility for an authority or agency such as a school district. The proceeds of the issue would be used to build the facility that is then leased to the agency and the lease payments will support the bond's debt service.

Special Tax Bonds

A special tax bond is issued to meet a specific goal. The bond's debt service is paid only by revenue generated from specific taxes. The debt service on special tax bonds is, in many cases, supported by “sin” taxes, such as taxes on alcohol, tobacco, gasoline, hotel and motel fees, and business licenses. Keep in mind that special tax bonds are revenue bonds, not general obligation bonds.

Special Assessment Bonds

A special assessment bond will be issued in order to finance a project that benefits a specific geographic area or portion of a municipality. Sidewalks and reservoirs are examples of projects that may be financed through issuance of special assessment bonds. The homeowners in the area that benefit from the project will be subject to a special tax assessment. The assessment then will be used to support the debt service of the bonds. Homeowners that do not benefit from the project are not subject to the tax assessment.

Double-Barreled Bonds

Double-barreled bonds are bonds that have been issued to build or maintain a revenue-producing facility such as a bridge or a roadway. The initial debt service is supported by the user fees generated by the facility. However, if the revenue generated by the facility is insufficient to support the bond's interest and principal payments, the payments will be supported by the general tax revenue of the state or municipality. The debt service on double-barreled bonds is backed by two sources of revenue. Because the tax revenue of the state or municipality also backs them, revenue bonds are rated and trade like general obligation bonds.

Moral Obligation Bonds

A moral obligation bond is issued to build or maintain a revenue-producing facility such as a park that charges an entrance fee or a tunnel that charges a toll. If the revenue generated by the facility is insufficient to cover the debt service, the state legislature may vote to allocate tax revenue to cover the shortfall. A moral obligation bond does not require that the state cover any shortfall; it merely gives them the option to. Some reasons why a state may elect to cover a shortfall are to:

- Keep a high credit rating on all municipal issues

- Ensure that interest rates on their municipal issues do not rise

New Housing Authority/Public Housing Authority

New housing authority (NHA) and public housing authority (PHA) bonds are issued to build low-income housing. The initial debt service for the bonds is the rental income received from the project's tenants. Should the rental income be insufficient to cover the bond's debt service, the U.S. government will cover any shortfall. Because the payments are guaranteed by the federal government, NHA/PHA bonds are considered to be the safest type of municipal bond. NHA/PHA bonds are not considered to be double-barreled bonds because any shortfall will be covered by the federal government, not the state or municipal government.

Short-Term Municipal Financing

States and municipalities, like other issuers, need to obtain short-term financing to manage their cash flow and will sell both short-term notes and tax-exempt commercial paper. Short-term notes are sold in anticipation of receiving other revenue and are issued an MIG rating by Moody's investor service. The MIG ratings range from 1 to 4, with a rating of MIG 1 being the highest and a rating of MIG 4 being the lowest. The types of short-term notes a state or municipality may issue are:

- Tax anticipation notes (TANs)

- Revenue anticipation notes (RANs)

- Bond anticipation notes (BANs)

- Tax and revenue anticipation notes (TRANs)

Municipal tax-exempt commercial paper matures in 270 days or less and usually will be backed by a line of credit at a bank.

Taxation of Municipal Bonds

The interest earned by investors from municipal bonds is free from federal income taxes. The doctrine of reciprocal immunity, established by the Supreme Court in 1895, sets forth that the federal government will not tax the interest earned by investors from municipal securities and that the states will not tax interest earned by investors on federal securities. The decision that established this doctrine was repealed in 1986 and allows for the federal taxation of municipal bond interest. This, however, is highly unlikely.

Tax-Equivalent Yield

It's important for investors to consider the tax implications of investing in municipal bonds. Because the interest earned from municipal bonds is federally tax free, municipal bonds will offer a lower rate than other bonds of similar quality. Even though the rate is oftentimes much lower, the investor may still be better off with the lower rate municipal than with a higher rate corporate bond. Investors in a higher tax bracket will realize a greater benefit from the tax exemption than investors in a lower tax bracket. To determine where an investor would be better off after taxes, look to the tax-equivalent yield that is found by using the following formula:

For example, take an investor considering purchasing a municipal bond with a coupon rate of 7%. The investor is also considering investing in a corporate bond instead. The investor is in the 30% federal tax bracket and wants to determine which bond is going to give the greatest return after taxes.

In this example, if the corporate bond of similar quality does not yield more than 10%, then the investor will be better off with the municipal bond. However, if the corporate bond yields more than 10%, the investor will be better off with the corporate bond.

Purchasing a Municipal Bond Issued in the State in Which the Investor Resides

If an investor purchases a municipal bond issued within the state in which he or she resides, then the interest earned on the bond will be free from federal, state, and local income taxes.

Triple Tax Free

Municipal bonds that have been issued by a territory such as Puerto Rico or Guam are given tax-free status for the interest payments from federal, state, and local income taxes.

Original Issue Discount (OID) and Secondary Market Discounts

Purchasers of original issue discount bonds, as well as those that have been purchased in the secondary market, are required to accrete the discount over the number of years remaining to maturity. That is to say, the investor must step up their cost base by the annualized discount each year.

Amortization of a Municipal Bond's Premium

Investors who purchase municipal bonds at a premium are required to amortize the premium over the number of years remaining to maturity. That is to say that the investor must step down their cost base by the annualized premium each year.

Bond Swaps

An investor from time to time may wish to sell a bond at a loss for tax purposes. The loss will be realized when the investor sells the bond. The investor may not repurchase the bond, or a bond that is substantially the same, for 30 days after the sale is made. The investor may purchase bonds that differ as to the issuer, the coupon, or maturity, thus creating a bond swap and not a wash sale. A wash sale would result in the loss being disallowed by the IRS, because a bond swap does not affect the investor's ability to claim the loss.

Analyzing Municipal Bonds

The quality and safety of municipal bonds vary from issuer to issuer. Investors who purchase municipal securities need to be able to determine the risk that may be associated with a particular issuer or with a particular bond.

Analyzing General Obligation Bonds

The quality of a general obligation bond is largely determined by the financial health of the issuing state or municipality. General obligation bonds are supported through the tax revenue that has been received by the issuer. The ability of the issuer to levy and collect tax revenue varies from state to state and from municipality to municipality. It is important that the fundamental health of the issuer be examined before investing in municipal bonds. Just as an investor would read a company's financial reports before purchasing their stock or bonds, an investor should read a state or municipality's reports before purchasing their bonds.

Duration

In a normal interest rate environment, longer-term bonds will pay investors a higher interest rate than short-term bonds of equal quality. As interest rates change, the price of existing bonds will move inversely to the change in interest rates. A bond's duration is a measure of the bond's price sensitivity to a small change in interest rates and is stated in years. Longer-term bonds and bonds with low coupons will generally have a higher duration than shorter-term or higher-yielding bonds. The higher the bond's duration, the greater the bond's interest rate risk and the greater its price volatility. Duration allows investors to compare the interest rate risk associated with bonds of different maturities, quality, and coupons. The bond's duration may be stated as either modified duration or effective duration. Modified duration assumes that a change in interest rates will not affect the bond's expected cash flow. Effective or call-adjusted duration assumes that a change in interest rates may affect the bond's cash flow if the bonds are callable or have other options for early retirement. Call-adjusted duration is lower than the bond's duration to maturity. All bonds that make regular interest payments will have a duration that is lower than the number of years to the bond's maturity. Because a zero-coupon bond does not provide any cash flow other than its principal payment at maturity, a zero-coupon bond's duration will be equal to the number of years to maturity. For example, a 20-year zero-coupon bond would have a duration of 20. To determine a bond's duration, use the following formula:

Convexity

A bond's convexity measures its price volatility to large changes in interest rates. A bond's price will not respond equally to both an increase and decrease in interest rates. As interest rates fall, bonds tend to increase in price more than they would fall if interest rates were to rise by an equal amount. Bond prices tend to rise faster in response to a fall in interest rates and fall slower in response to a rise in interest rates. Bonds whose prices react in this way are said to have positive convexity. Mortgage-backed and callable bonds tend to have negative convexities. A fall in interest rates increases both mortgage prepayments and the likelihood that the bonds will be called. Convexity is a better risk management tool than duration in volatile interest rate environments or when interest rates are low.

Bond Portfolio Management

Bond portfolios may be either actively or passively managed to meet the needs of different investors. Active portfolio management tends to seek an above-average total return for the portfolio. The portfolio's total return includes:

- Coupon return: the total of all interest payments received by the portfolio plus accrued interest earned during a specific holding period

- Reinvestment return: the total interest earned from the reinvestment of interest payments during a specific holding period

- Price return: the total of the portfolio's appreciation or depreciation during a specific holding period

For long-term holding periods, the portfolio's reinvestment return will be the most important factor when determining the portfolio's return. For holding periods between two to 10 years, the coupon return and reinvestment return will be the most important factors. For short-term holding periods, the price return will be the most important factor.

Passive bond portfolio management includes both indexing and buy-and-hold strategies. Portfolio managers who use indexing try to match the performance of a given bond index by purchasing bonds that are included in the index. Advantages of indexing include lower management fees, diversification, and more predictable performance. Buy-and-hold managers tend to purchase bonds in the primary market and hold them for long periods of time or until maturity. By consistently purchasing new issues of bonds, the portfolio manager can maintain diversification of terms and coupon rates.

Pension and insurance company portfolio managers often will try to manage the portfolio's income to meet the current cash obligations of the pension plan or the insurance company's guaranteed investment contracts. Two methods used to match the portfolio's income with current cash liabilities are dedicated portfolio management and bond immunization. Dedicated portfolio management matches the portfolio's monthly income with the monthly cash liabilities. Bond immunization creates a portfolio designed to generate a specific return during a known time horizon. Portfolio managers using bond immunization will match the bonds' maturity dates with the known time when a lump sum payment is due. Because the portfolio's maturity dates match the time when the payment is due, the portfolio is said to be immunized from interest rate risk.

Chapter 2

Pretest

Corporate and Municipal Debt Securities

- An investor has purchased 10 corporate bonds at a price of 135. At the end of the day, the bonds are quoted at 136.25. How much have the bonds risen in dollars?

- $125

- $12.50

- $1.25

- $.125

- Which type of bonds require the investor to deposit coupons to receive their interest payments but have the owner's name recorded on the books of the issuer?

- Registered bonds

- Bearer bonds

- Book entry/journal entry bonds

- Principal-only bonds

- In response to a customer's request for information on how inflation will affect their return realized from their semiannual coupon payments, you would look at the:

- real interest rate.

- adjusted interest rate.

- interest conversion rate.

- current interest rate.

- Which bonds are issued as a physical certificate without the owner's name on them and require whoever possesses these bonds to clip the coupons to receive their interest payments and to surrender the bond at maturity in order to receive the principal payment?

- Registered bonds

- Book entry/journal entry bonds

- Principal-only registered bonds

- Bearer bonds

- All of the following are reasons a corporation would attach a warrant to their bond, except to:

- save money.

- make the bond more attractive.

- increase the number of shares outstanding when the warrants are exercised.

- lower the coupon.

- The type of bond that is secured by real estate is called:

- Real estate trust certificates

- Mortgage bond

- Equipment trust certificates

- Collateral trust certificates

- Collateral trust certificates use which of the following as collateral?

- Real estate

- Mortgage

- Stocks and bonds issued by the same company

- Stocks and bonds issued by another company

- An investor holding an 8% subordinated debenture will receive how much at maturity?

- $1,000

- $1,080

- $1,040

- Depends on the purchase price

- An ABC corporate bond is quoted at 110 and is convertible into ABC common at 20 per share parity. Price for the stock is:

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- An investor buys $10,000 of 10% corporate bonds with 5 years left to maturity. The investor pays 120 for the bonds. The approximate yield to maturity is:

- 5.45%

- 11.1%

- 6%

- 9.2%

- XYZ has 8% subordinated debentures trading in the market place at $120. They are convertible into XYZ common stock at $25 per share. What is the parity price of the common stock?

- 29

- 31

- 30

- 28

- Which one of the following debt securities pays interest?

- Commercial paper

- T-bill

- Industrial revenue bond

- Banker's acceptance

- An investor would expect to realize the largest capital gain by buying bonds that are:

- long term when rates are high.

- short term when rates are low.

- short term when rates are high.

- long term when rates are low.