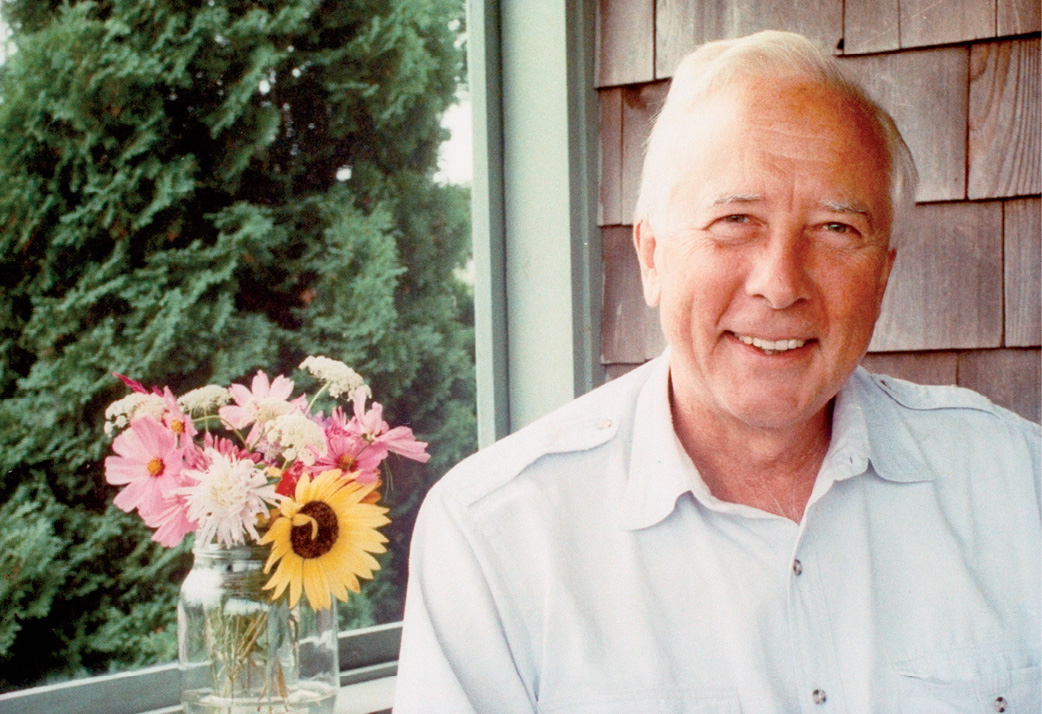

ALFRED EISENSTAEDT

McCullough very much at home on the Vineyard in 1990 in a portrait made by his friend and neighbor, LIFE’s famed alfred Eisenstaedt.

Foreword

“A Death in the American Family”

A Conversation with David McCullough

The historian helps us understand why John Fitzgerald Kennedy still matters—and why he mattered greatly to McCullough himself, 50 years ago.

THE PREEMINENT AMERICAN HISTORIAN OF our time is David McCullough. Some critics might put forth a second or third nominee, but we’re in McCullough’s camp. Twice a Pulitzer Prize winner and also the recipient not only of a National Book Award but also our nation’s highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the 80-year-old native of Pittsburgh has for years spent the nice months living and writing on the island of Martha’s Vineyard, just across the sound from the Kennedy compound in Hyannis Port, Massachusetts.

Particularly when it comes to John F. Kennedy, McCullough is well suited to set the stage for us. It’s not that he is a JFK biographer or a chronicler of the family—he isn’t, at least not yet—but he has analyzed and thought for many years about the grand sweep of American and presidential history, and also, when he was a younger man, he himself was swept up by the Kennedy aura. In fact, he found his calling after having been influenced by Kennedy’s deep personal interest in history. Moreover, here at Time Inc., the parent company of LIFE Books, McCullough is not only a proud alumnus, but was working for the firm when JFK went to the White House. McCullough, too, quickly went to Washington and likewise found employment in the government (albeit in a position of different scope and scale). Told that LIFE is commemorating the life and legacy of John Fitzgerald Kennedy, 50 years on, McCullough says he is happy to help, and, remembering the magazine’s coverage of the time, adds graciously, “It’s great you’re doing this. It’s wonderful. You’re the right ones to do it.”

McCullough is at home today on a pleasant day in late May, as rising temperatures are finally chasing away a chilly spring. He is asked to begin with the professional perspective: What is it about Kennedy? Why, a half century on, is such attention still paid to him, who after all had such a relatively brief residence at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue?

“Well, I think there are several reasons really,” he answers. “There are three things I would put at the head of the list for why Kennedy is remembered. One thing is, and this is pretty obvious, Kennedy was glamorous in a way that no President has been in the lifetimes of most Americans. He might have been the most glamorous President ever. His wife and children were glamorous. He had tremendous personal charisma. He had a phenomenal gift for using the language to lift the country’s spirits, and in this he wasn’t unlike FDR. I loved that he loved books, he loved culture; he was eloquent as very few leaders ever have been. In these ways, he was approaching the same type of leader as Winston Churchill.

“On the same point, he was the first President to really use television, particularly of course with his inaugural address but also his subsequent addresses and his spectacular press conferences. He knew how to use humor, a self-deprecating humor, not unlike Reagan, that was very appealing. We remember that.

“Most of us knew nothing about his private excesses, I never even heard gossip about it. Things went on that people never knew back then.” So the image was intact and for some permanently so: fine-looking family man. Churchgoer, too.

That’s the second thing, says McCullough: “He broke the religious barrier. This was very important; it might be hard for some people today to realize how important. And he did this by never apologizing for or dismissing the importance of Catholicism in his life. He took the issue head-on.

“And he said we would go to the moon. That was a vastly important objective he set for us.” It was important, McCullough asserts, not only in terms of the cold war battle with the Soviets that had the country on edge, but in terms of America’s own spirit and sense of achievement and aspiration. “He knew life was unfair and said so,” McCullough continues, “but he was an optimist. The people liked that in him; they loved it.” Sending a man to the moon would be a perfect and perfectly outrageous accomplishment—symbolic, metaphoric, but actual—for a nation forming itself in their leader’s can-do spirit.

So there were those three large issues and aspects at work—the glamour and youth and vitality, the forcing of his country to overcome prejudice, the encouraging of his countrymen to join him in daring to dream—and then he was murdered. “The way he looked, he was always so photogenic,” says McCullough. “He really was perfect for the hero part. And of course he had the actual heroism of his war service. So: the handsome one who was killed. The hero was sacrificed.” Such a narrative as that will never be forgotten.

At this point the discussion with McCullough turns to a judgment of the man and his time in office: He had the Bay of Pigs disaster but then the successful outcome of the Cuban missile crisis, he initiated policies that would lead to the civil rights achievements of President Lyndon Johnson’s term but also to the mire that would be the Vietnam War. “I don’t think you could say he was a great President,” says McCullough. “His time in office was a little bit too short. A good part of the time, that last year or so, he was in the soup. There was a lot of criticism. I don’t think [the fault-finding] was of him personally so much as simply for the way things were going [in the country].

“Truman said that you need 50 years of time to go by in order to pass judgment, and I think that’s right. You can’t say he was a great President. But [Kennedy] is among our most remembered Presidents, and I think he always will be.”

MCCULLOUGH IS A GOOD HISTORIAN—he’s a great one—and this is herein confirmed because there’s an inference on the part of his listener that McCullough wishes he could give Kennedy a complete, and better, grade. As a chronicler being asked his opinion, however, he cannot; he’s got a job to do.

“Whatever I say about him, I’m speaking from the bias of having been swept away by his candidacy.

“I was young, I was working for Time Inc., I had a very good job. I had been there six years, had started out at Sports Illustrated as a trainee, and I was a huge enthusiast for architecture and had gone to work for The Architectural Forum as a writer, and then I went over to Time, and now I was nearing 30. I had a family and we had income, but right then Kennedy began to run and I got swept up with it. I quit my job and went down to Washington having no inside [angle] on any job. I went to the United States Information Agency [a government service] and the man who interviewed me was Don Wilson, who had been the head of the LIFE bureau in Washington. Don had worked on the campaign and was very close to the administration. He knew Kennedy well. He was made number two at USIA, second to Edward R. Murrow. I didn’t know Don, but Don checked my credentials back in the home office, and he hired me and put me in charge of a magazine for the Arab world. I had never run a magazine, I didn’t know anything about the Arab world, I knew nothing about the Arabs, and I told him so. ‘How much do you know about the Arabs?’ ‘Mr. Wilson, I don’t know anything about the Arabs.’ ‘Well,’ he said, ‘you’re gonna learn a lot.’ Those were terrific times, it was so exciting.”

It all trickled down from Kennedy and the energy—the vibe—of the White House: “As I say, I’m not a Kennedy scholar, but I experienced some of the effect he had on people and the country. I was so emotionally and personally involved in that story at that point in time, and I was so excited, and the thing was: We young, like him, were having a chance at failure. That was encouraged by him. At the beginning I was thinking, ‘I’m in so over my head,’ but six months later: ‘Maybe I’m not in over my head, and this is my job. Maybe I can do this.’ That was him.

“And we put out a very good lifestyle magazine for the Arab world—produced in Washington, translated into Arabic in Beirut—very good, if I do say so.”

“Years later, I met Barbara Tuchman at a party and she told me how much she admired my work, and I thought I was about to go soaring off through the ceiling.”

AS WILL BE ASKED OF many others later in this LIFE commemorative, McCullough is asked: “Where were you when you heard?”

“On the day he was shot,” McCullough begins, and then he goes down a tangential road briefly. “Well, I should tell you, people don’t appreciate this enough today: There was great worry when he announced he was going to Dallas. I really think people don’t know that today. Back in that time, many people in Washington were saying, ‘Oh, God, he shouldn’t go there.’ There really was that feeling of dread.

“I was having lunch with Don Wilson at a restaurant called, ironically, the Black Saddle, right around the corner from our offices at 1776 Pennsylvania, near the White House. And at one point an associate—I can’t remember his name, it’s not important—came in just as we were about to order lunch, and leaned over and whispered something in Don’s ear, which I couldn’t hear. And Don looked up and said, ‘The President’s been shot! Which President?’ He couldn’t accept that this had happened to his President. They had been good friends. I remember that after Kennedy was killed, Don left and went back to LIFE.

“From that moment on, we were working virtually night and day, as you might imagine, trying to put things out to explain to the world what had happened, and not only do justice to the fallen President but to tell the world something about Lyndon Johnson, the new President.

“For me, it was the most wrenching experience I had ever gone through, and I think the most wrenching experience I’ve gone through since—both emotionally, and [because of] the tremendous pressure that was put on us with the work.

“In a way, the work was a blessing, because for those of us who [cared about] Kennedy, it helped take our minds off what had happened.

“For us, who were excited at the time, to have the whole thing blow up like that: We were all saying, ‘Oh, God!’”

But of course it wasn’t just earthshaking for the young: “It was a national heartbreaker—a national heartbreaking experience,” says McCullough. “It was not just a death in the family, it was a death in the American family.”

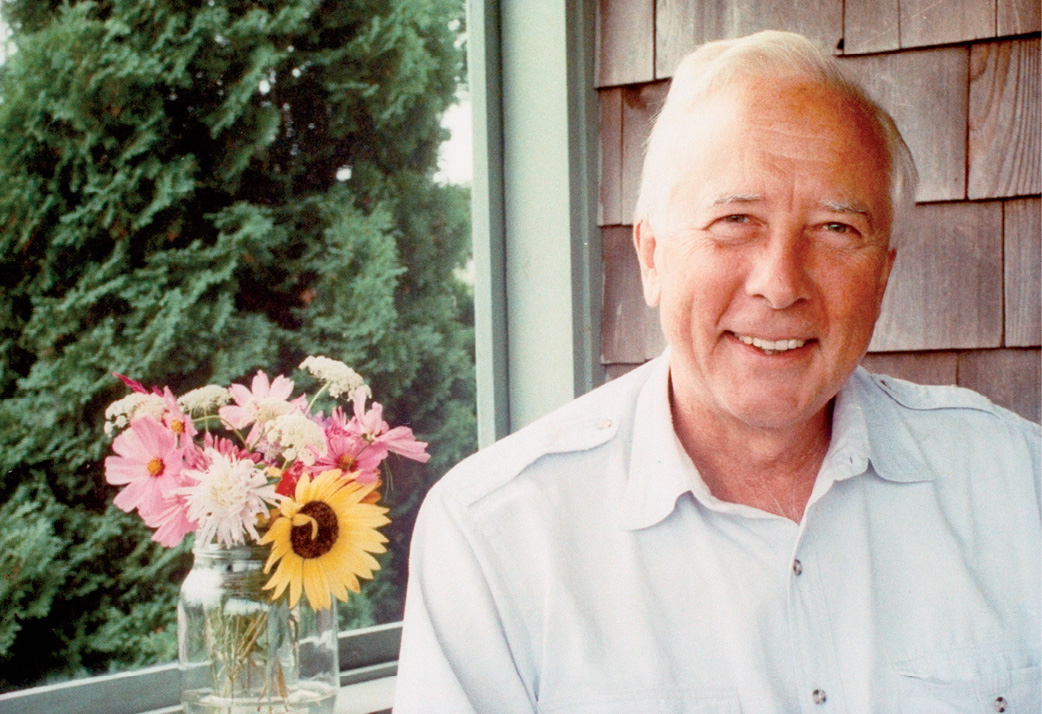

ALFRED EISENSTAEDT

McCullough very much at home on the Vineyard in 1990 in a portrait made by his friend and neighbor, LIFE’s famed alfred Eisenstaedt.