That Day in Dallas

He had been warned not to go by those in his administration who simply didn’t like Texas. He had been urged to go by his Vice President and others who either loved Texas or knew how important Texas would be to his reelection. In the event, he went.

DEALEY PLAZA. OF ALL OF the domestic place-names that resonate in American history—Concord and Lexington, the Alamo, Gettysburg, Ford’s Theatre, Pearl Harbor, the Twin Towers—this is perhaps the most prosaic. It’s a city park in Dallas, but a small one, nothing like the Dealey Plaza that has grown immense in the national imagination. It was born of a Works Progress Administration project in the late 1930s on the west edge of downtown because there was a bit of donated land and a man, newspaper publisher George Bannerman Dealey, lobbying for a cleanup. Main Street, Elm Street and Commerce Street came together there and, sharing a triple underpass, passed beneath a railroad bridge. Let’s prettify this place, thought Dealey.

Two decades later—50 years ago—John F. Kennedy’s presidential motorcade cruised down into the plaza, and the events of the next few moments bequeathed to this site—and city—the kind of fame, or infamy, none would ever seek.

Why was Kennedy in Dallas? There are short and long answers to that question, but the shortest, perhaps, is this: He wasn’t well loved there. No one realized this better than the canny JFK, raised a politician on Joe Sr.’s knee, and JFK’s Vice President, Lyndon Johnson, who was as representative of Texas as the state flag. “The trip was presidential politics, pure and simple,” wrote LBJ in his 1971 book, The Vantage Point. “It was the opening effort of the 1964 campaign. And it was going beautifully.”

The Kennedy-Johnson ticket had won delegate-rich Texas by only a slim margin in the 1960 election and had done poorly in Dallas. The state was growing increasingly divided between liberals (spearheaded by Senator Ralph Yarborough) and conservatives (whose figurehead was a Democrat of a different stripe, Governor John Connally). The Texas salvo in 1963, baldly in search of financial and electoral support, would include motorcades in five cities—San Antonio, Houston, Fort Worth, Dallas and Austin. Air Force One landed in San Antonio with not only JFK aboard but the road show’s surprise star attraction, Jacqueline Kennedy. She didn’t often accompany her husband on political trips, and this would be her first series of official appearances since her infant son, Patrick, had died shortly after his birth on August 7.

On the 21st, Jack wowed them in San Antonio, where he was cheered during the dedication of an aerospace medical center, and Jackie thrilled them in Houston, where she addressed an audience in Spanish. They arrived in Fort Worth before midnight, and then the President was up early, walking the street in the rain, greeting his fans. From there, on to Dallas, where the barnstorming tour was greeted by yet more rapturous fans at Love Field airport—and also a full-page advertisement taken out that morning in The Dallas Morning News by the so-called (and, in truth, nonexistent) “American Fact-Finding Committee” that read in part: “Welcome Mr. Kennedy to Dallas,” a city that was victim of “a recent Liberal smear attempt” but that had risen above, “despite efforts by you and your administration to penalize it for nonconformity to ‘New Frontierism.’” The ad went on to link Kennedy and his brother Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy to communists, “fellow-travelers, and ultra-leftists,” and to efforts to “persecute loyal Americans.”

President Kennedy had many more friends in Dallas than he had enemies. But he did have enemies, including others not at all affiliated with the American Fact-Finding Committee.

HARVEY GEORGES/AP

Final rituals in Washington: It was late November, and so there would be a photo-act at the White House (above) with a 40-pound turkey. Standing at center is Senator Everett Dirksen of Illinois, and in the assembly are turkey farmers and the president of the National Turkey Federation. Kennedy sent the gobbler back to its farm, saying, “We’ll just let this one grow.”

BETTMANN/CORBIS

Jackie, the guest superstar of the Texas tour, waves goodbye before boarding Air Force One in Washington.

11/21/63

San Antonio

ARTHUR RICKERBY

The Kennedys are in San Antonio on the 21st, joined in the limo by their formal hosts in Texas, Governor John Connally and his wife, Nellie.

ARTHUR RICKERBY

The Kennedys are joined on stage at the aerospace center by the über-Texan, Vice President Lyndon Baines Johnson. Kennedy’s relationship with both these Lone Star Staters was complicated, and probably would have been nonexistent were it not for the political circumstance of being ambitious members of the same party. Connally had supported Senator Lyndon Johnson for President in 1960, going so far as to try to undermine Kennedy’s candidacy by calling a press conference to discuss JFK’s Addison’s disease and the drugs he took to stay alive. Nevertheless, Kennedy made his fellow World War II veteran secretary of the Navy, a post Connally would relinquish to run for governor. Connally’s politics were far to the right of Kennedy’s, and in fact in 1973 he would switch to the Republican side; he would serve as secretary of the Treasury under President Richard M. Nixon. As for Johnson, his problems with the Kennedys could fill—and have filled—volumes; if he didn’t like Jack overly much, he liked his brother Bobby much less. But JFK, upon receiving the nomination at the convention in Los Angeles in 1960, realized he needed Southern Democratic support in the general election in order to prevail, and offered—over the protests of aides—the number two spot on the ticket to Johnson, who accepted with teeth clenched. But everyone was smiling in San Antonio.

11/21/63

Houston

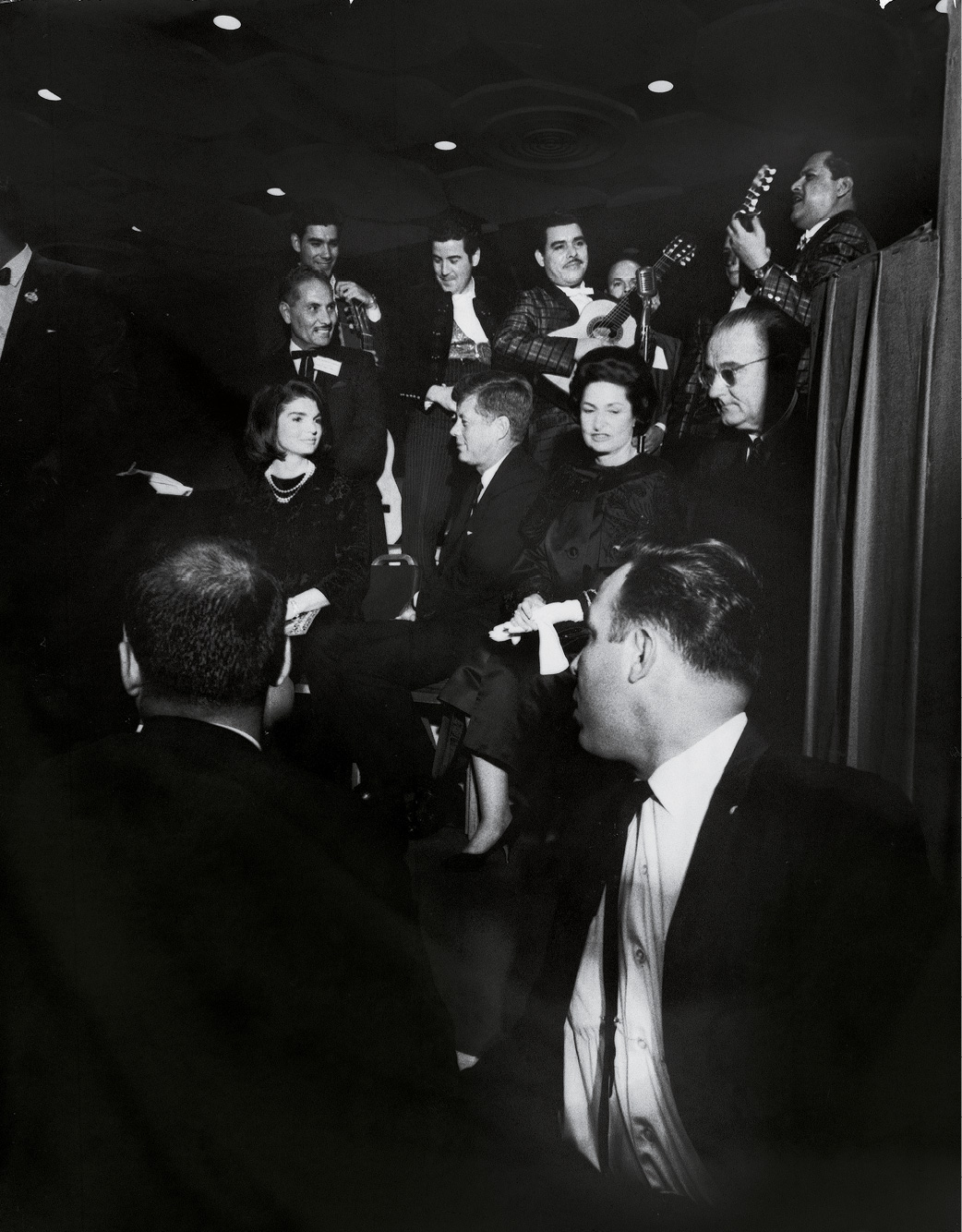

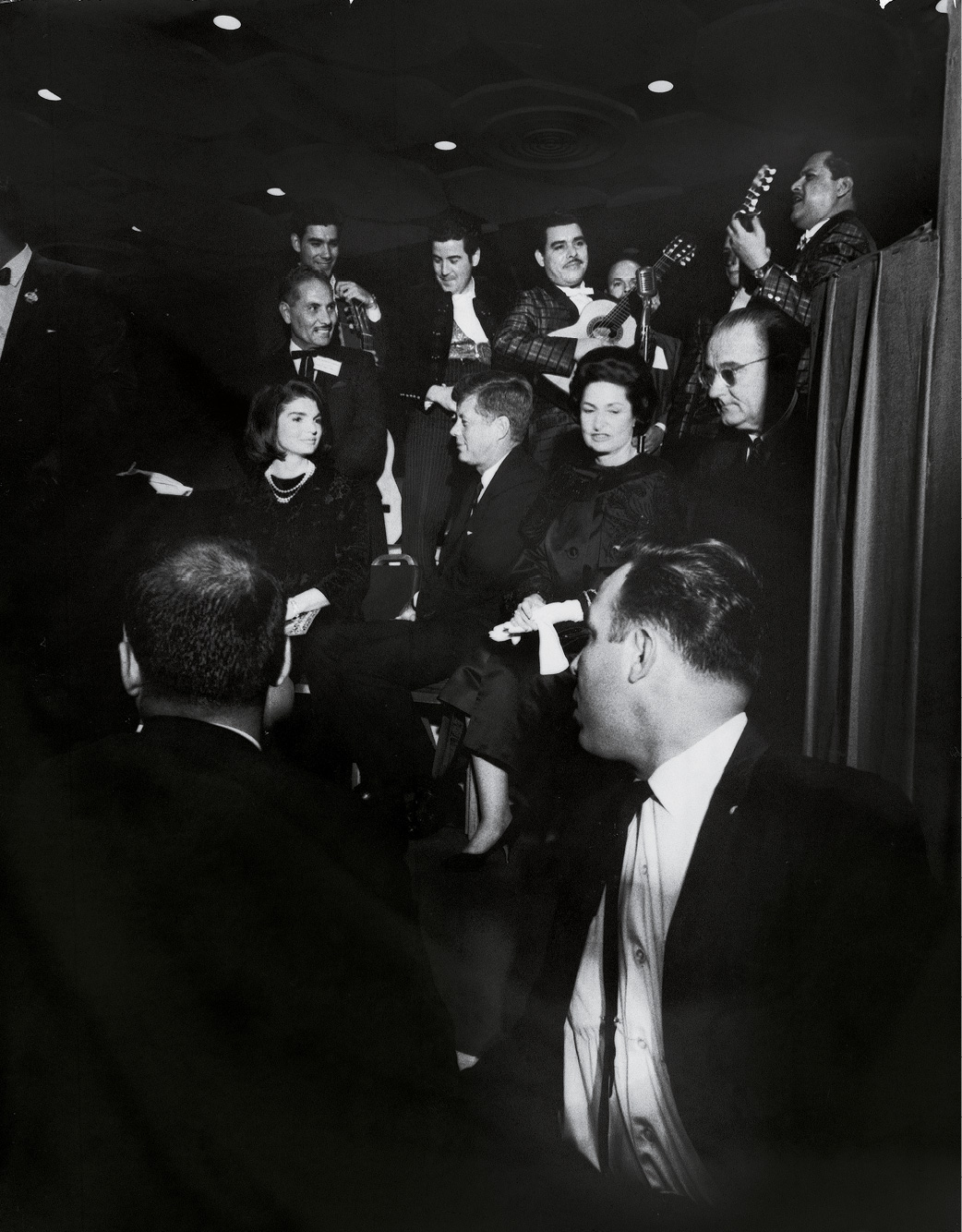

ARTHUR RICKERBY

Today in Houston there is a John F. Kennedy Elementary School and a boulevard named for the late President; on the boulevard is a store called JFK Liquors. On November 21, 1963, when these photos were made in that city, such future commemorations for this alien being from Massachusetts were unimaginable. It’s not that things didn’t go well on the 21st for Kennedy; they in fact went splendidly. But if Houston feted Kennedy, no one suspected Houston loved him. The motorcade, with heavy security after careful planning, came off fine, as did the speech at the Rice Hotel, as did the dinner in honor of local U.S. congressman Albert Thomas at the Sam Houston Coliseum (above).

MICHAEL QUAN/ZUMA

The appearance at a meeting of the League of United Latin American Citizens, where Jackie broke out her Spanish, also went well. The Kennedys seemed to be making all the right moves in Texas, and with each city checked off the list, everyone in the entourage breathed more easily.

ARTHUR RICKERBY

As Lyndon Johnson, who was proudly showing off his native state (in dark glasses, with his wife, Lady Bird, at the LULAC dinner), later wrote, not without lament, the tour was going beautifully indeed.

11/22/63

Fort Worth

OWEN DAY/DANA DAY HENDERSON COLLECTION

Day one of the Texas swing wound up in Fort Worth. At about 11:50 p.m. the Kennedys checked in to Suite 850 of the Hotel Texas. Of course it was nicely arrayed (above), but the President and First Lady could not help but notice a relatively extraordinary display of artwork on the walls: not home-on-the-range paintings at all, but a thoughtfully assembled selection including modernists such as Lyonel Feininger (his “Manhattan II”) and Franz Kline. This had obviously been planned—a small group of local art lovers had curated—and the Kennedys were impressed, even touched. On the morning of the 22nd, JFK made several phones calls from his suite, and it is now believed the last call he made in his life was to Ruth Carter Johnson to thank her for her and her friends’ extra effort with the art. This is one of the small stories—which are not really small at all, but human—that have endured because of what happened later that day. In the run-up to the 50th anniversary of the assassination, the Dallas Museum of Art has sponsored an exhibit of the paintings; and Suite 850, in what is today the Hilton Fort Worth, is represented just as it was when a tired President and his wife, both happy with the trip so far, caught 40 winks.

CORBIS

Later in the morning, when the Kennedys left the hotel and walked to a borrowed convertible, Jackie was sporting what has become perhaps the most famous suit ever worn by anyone, ever—male or female. She had in fact already featured it numerous times on public occasions, and chose it again this day at her husband’s request; it was one of his favorites. These days, everyone knows it was pink, but in 1963 most of the public didn’t, because very few newspapers or magazines ran color photography. Yes, it was a Coco Chanel design—her 1961 autumn/winter collection—but no, it was not a Chanel; Jackie’s was a high-end reproduction by Chez Ninon, a New York salon, using fabric and buttons supplied by Chanel. (These days, it would be called a knock-off.) Much of the rest that you think you know about the suit is true: Jackie refused to change out of it until the next morning in the White House, so people could see what had happened through the bloodstains. The suit is today in the National Archives, unwashed, having been deeded by Caroline Kennedy in 2003 and is now kept in a secret location with the provision it not be seen by the public until 2103. The whereabouts of the pillbox hat are today unknown.

CECIL STOUGHTON/REUTERS/LANDOV

“Where’s Jackie?” That’s what the crowd in a parking lot on Eighth Street in downtown Fort Worth wants to know, and the President points, indicating that she’s still upstairs and will be down in a minute.

ARTHUR RICKERBY

At the Forth Worth Chamber of Commerce breakfast that follows the outdoor rally and brief speech, the main attraction is applauded by Vice President Johnson and President Kennedy—and 2,500 other distinguished guests in the hotel ballroom. The morning in Fort Worth is a constant bustle: phone calls, up and down and up the elevator, the weather starting drizzly and turning sunny for the final motorcade through downtown en route to Carswell Air Force Base, where, at 11:25 a.m., the latest plane to be designated Air Force One, a Boeing 707, will take the party for the very short hop to Dallas. It’s busy and sometimes damp, this now-well-parsed morning in Fort Worth, but overall: festive. For one reason or another, probably having nothing to do with Kennedy’s visit but rather with rushing the shopping season, the city’s Christmas decorations are already up along the motorcade route, adding to the gaiety.

CLINT GRANT/THE DALLAS MORNING NEWS

Two more photos from the rally in Fort Worth: Kennedy, accompanied by Texan politicians Senator Ralph Yarborough (above, at far left) and Representative Jim Wright, eschews a raincoat as he crosses Eighth Street from the hotel to the parking lot just before nine a.m., and then shares the love with the damp but not dampened people who have come to see and hear him. Also alongside the President all morning and throughout the rest of the day, including on Air Force One on its way back from Dallas to Washington, is Cecil Stoughton, the first photographer to be hired as an official White House documentarian and a man responsible not only for several photographs in this book (many of which first appeared in LIFE magazine, a favorite outlet for the Kennedys) but for some of the most famous Kennedy photos ever (such as John-John and Caroline playing in the Oval Office; Jackie present, as we will see later in this chapter, at the hastily assembled swearing in of Lyndon Baines Johnson). Stoughton, a native Iowan born in 1920, enlisted in the Army Air Corps even before the U.S. entered World War II and, after Pearl Harbor, was assigned to take a LIFE magazine photography training course, then helped document the fighting in the Pacific Theater. He determined, postwar, to continue with photography in the military, and in 1961 was working at the Pentagon, assigned to shoot pictures of Kennedy’s inauguration. He did a good job, and it was suggested to Kennedy that it could be useful to have such a man as Captain Stoughton on hand full-time. Surely there had been photographers close to Presidents before, including several on LIFE’s staff, but Stoughton was given an office at the White House. Thus was born a post that today seems as integral a part of any administration as that of the press secretary.

CECIL STOUGHTON/THE WHITE HOUSE/JFK LIBRARY/REUTERS

11/22/63

Dallas

CECIL STOUGHTON /JOHN F. KENNEDY PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY, BOSTON

These photographs are, as earlier ones were, by Cecil Stoughton: of the President and First Lady arriving at Love Field in Dallas only minutes after leaving Fort Worth and less than an hour before the assassination. The thorough, accurate and eloquent archivist Richard B. Trask, who has delved deeply into such subjects as the long-ago Salem witch trials and the 20th-century killing of Kennedy, talked to Stoughton before his death and writes in his book, which happens to have the same title as this chapter in our own volume: “Stoughton recalls that the press expected a hostile atmosphere in conservative Dallas, but that ‘it sure didn’t spin off into the Love Field crowd. My pictures show dozens of flags, hand-painted welcome signs, a lot of warmth...I did not feel nor see any hostility, certainly not during the whole time we were there.’ Stoughton later recalled the scene as ‘just a beautiful reception, a bright, warm, sunny day and thousands of people cheering—screaming like they had at Fort Worth, Houston and San Antonio.’”

Of course, there were factions not represented at the remarkably named Love Field: Those behind that day’s advertorial in The Dallas Morning News; those in the streets with the sign that will be seen on the following pages; and, in a warehouse on Dealey Plaza, a man with a rifle.

CECIL STOUGHTON /THE WHITE HOUSE/JFK LIBRARY/REUTERS

JESSICA RINALDI/REUTERS/CORBIS

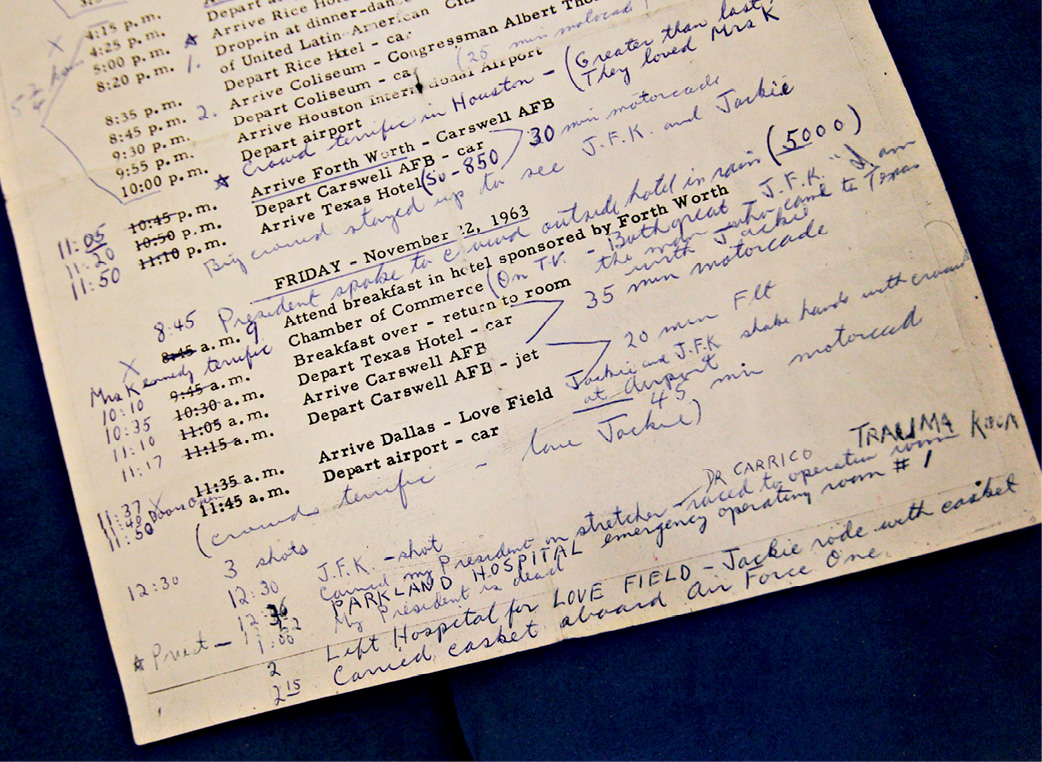

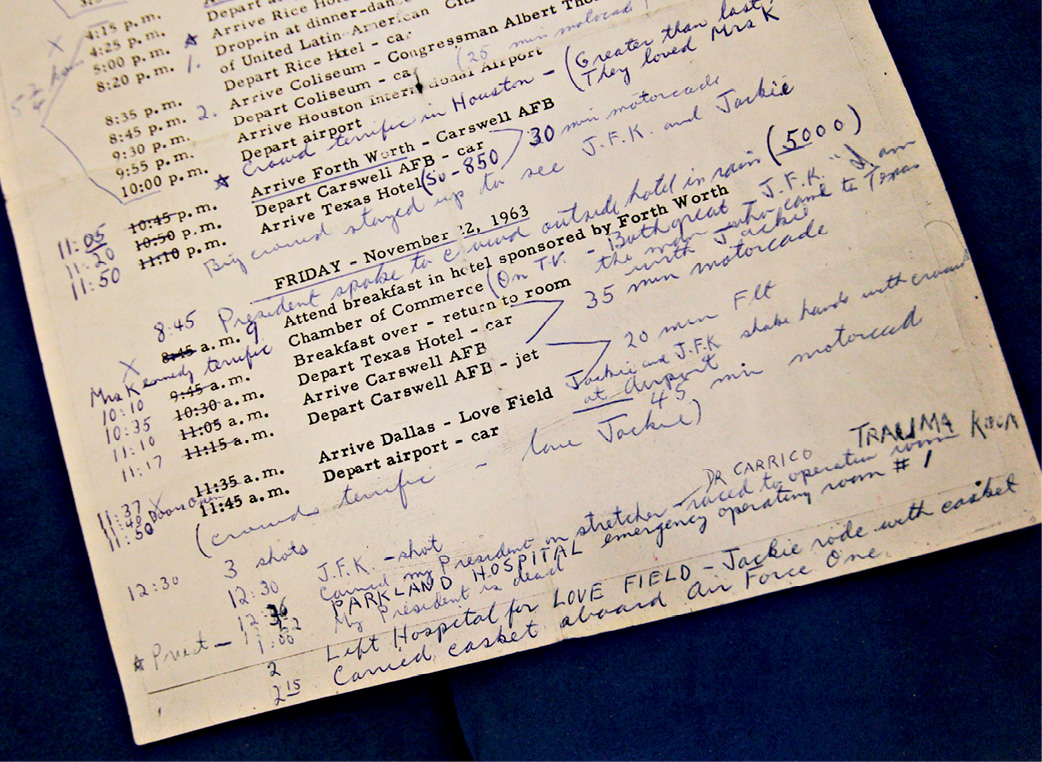

The handwritten notes are by Kennedy assistant David Powers.

TOM DILLARD/THE DALLAS MORNING NEWS

As you can tell from the timeline unfolding in this chapter, everything was coordinated to the nth degree and was happening very fast—this was as quick a multipurpose tour as could be staged in 1963. Dallas, a city of nearly a million people then, was the largest effort, but still the schedule there would be lightning fast: an open motorcade from Love Field through downtown, winding up at a luncheon for 2,600 close friends (and others) at the Trade Mart, which was north of downtown—just beyond Dealey Plaza. As Dallas had grown in those years, it had seemed to grow more conservative and, in its expanding weave, had seen “groups” spring up or burgeon. The John Birch Society and the Indignant White Citizens Council didn’t pretend to be strangers in Dallas, but whether the larger sign in the photo above, which bade Jack and Jackie farewell from Love Field, was wielded by members of one of those organizations is uncertain. For the younger among us: The “Barry” for “bury” refers to Arizona senator Barry Goldwater, a thoroughgoing conservative, who would indeed run against (and lose to) Lyndon Johnson in the 1964 presidential election.

BETTMANN/CORBIS

John F. Kennedy and Governor John Connally in the motorcade not long before bullets would hit the two men, fatally wounding the President. In the “Where Were You When You Heard?” chapter in our book, Jim Lehrer, then a reporter for the Dallas Times Herald, has a fascinating story about why the bubbletop shell was not in place on the limousine. There are also reports that, whatever the input of others, JFK himself insisted the car proceed without a roof once the weather turned from misty to sunny.

JAMES W. ALTGENS/AP

These images are not from the Zapruder film; that is dealt with extensively elsewhere in our book. There were certainly other still and film photographers paying attention to the motorcade as it proceeded into, then sped away from, Dealey Plaza. Moorman, Muchmore, Bronson and other names are attached to the evidence files, as is Zapruder. It’s interesting: The Dal-Tex building, seen above with the fire escapes prominent, is where Abraham Zapruder had his offices; this photo can imply the casual stroll he had to the pergola atop the grassy knoll.

Seen through the Lincoln Continental limousine’s windshield as it proceeds along Elm Street past the Texas School Book Depository at 11 miles per hour in this image, President Kennedy appears to raise his hand toward his head. Mrs. Kennedy holds his forearm in an effort to aid him. At just about this moment, the sound has registered with motorcycle police escort Bobby Hargis, who thinks to himself, Lord, let it be a firecracker. The picture was made within seconds of the President’s being fatally shot. Governor Connally, in the jump seat just ahead of JFK, is hit, too, and shouts, “Oh, no, no, no.”

RICHARD BOTHUN/THE DALLAS MORNING NEWS/CORBIS

In this photograph, the Newman family is on the ground in Dealey Plaza immediately after the shooting. Who were they? At the time Bill and Gayle—who are shielding their two- and four-year-old sons, Clayton and Billy—were a struggling young couple barely in their twenties. They had driven out to Love Field to see the President earlier, then had dashed back to town and wound up being the very closest eyewitnesses to Kennedy when the shots rang out. The father initially hoped, as had Officer Hargis, that he had heard firecrackers, then when the third bang issued he shouted, “That’s it. Get down!” and he and Gayle dove and shielded their boys. The elder Newmans, now in their seventies still live near Dallas.

BETTMANN/CORBIS

An NBC cameraman stands at the left as the Newmans hug the ground in those same moments after the assault. The last of the motorcycles are rushing away at speeds that will approach 80 miles per hour, and the President’s story is now moving to Parkland Memorial Hospital. Behind, in the Book Depository, Lee Harvey Oswald is on the move; on the plaza a frantic, scattered, confused and scared search ensues. Oswald, for a time, blends in to the city.

ARTHUR RICKERBY

Outside Parkland Memorial Hospital, a nurse is in tears.

ARTHUR RICKERBY

The scene is jammed with cars from the presidential motorcade and people anxious for news, while hospital employees try to focus on their duties.

TOM DILLARD/THE DALLAS MORNING NEWS

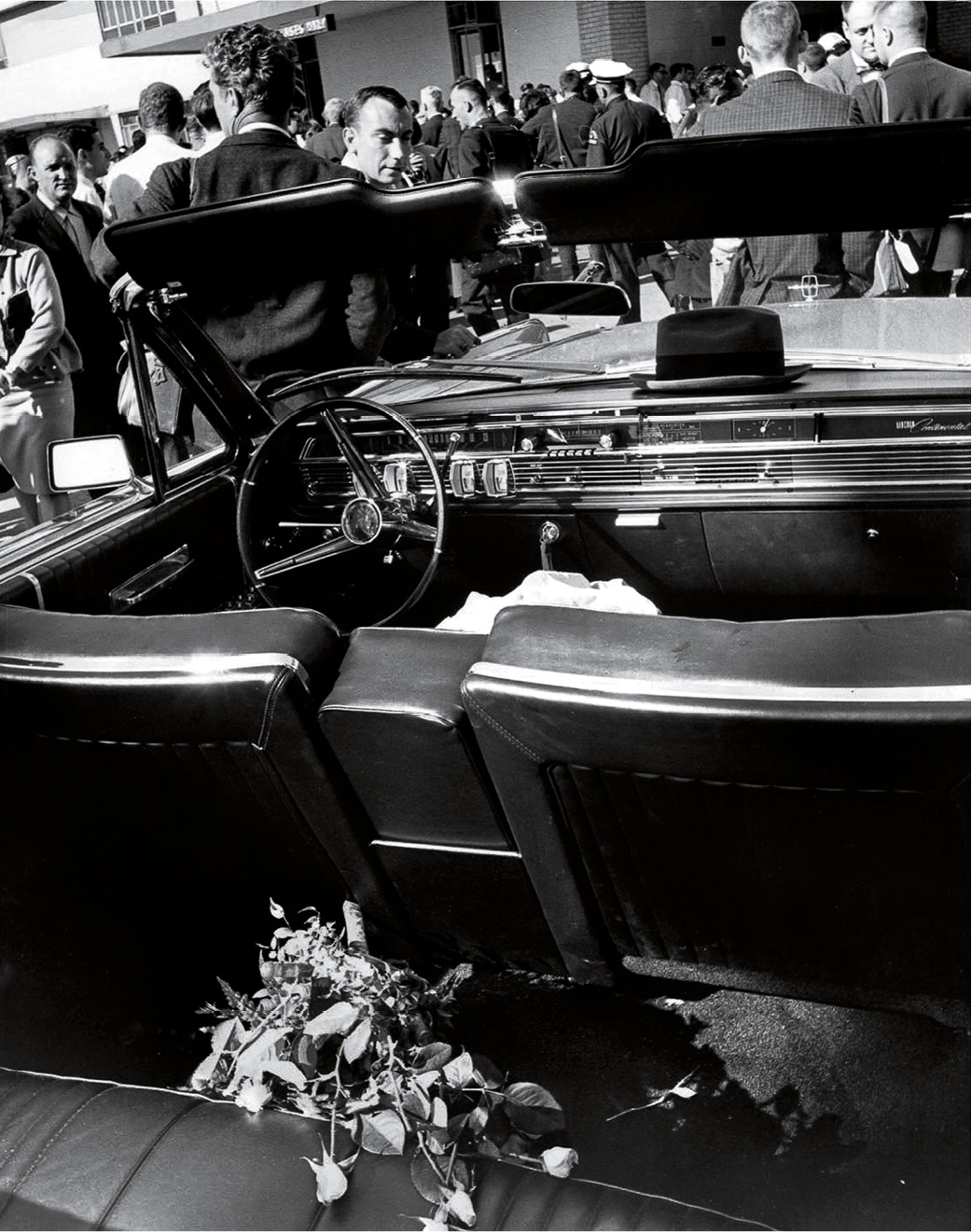

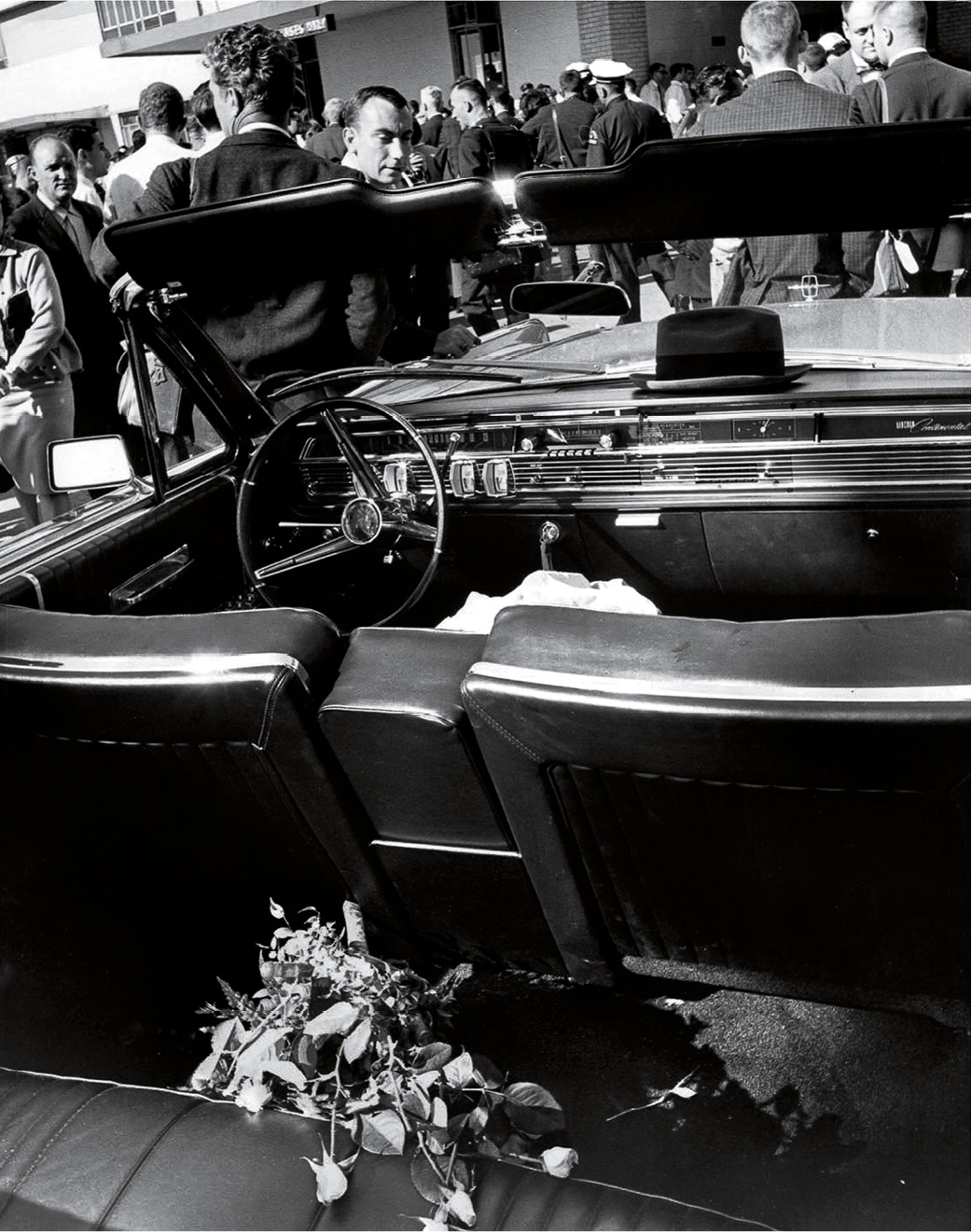

A bouquet of yellow roses lies on the floor of the limousine that transported the Vice President and his wife. This was and is an extremely poignant photograph, but the limousine has sometimes been misidentified as the President’s. The roses tell a tale: Some of the wives had been given yellow roses at Love Field airport, but Jackie’s were red. Jackie herself told Theodore White how three times that day she had been given a bouquet of the yellow roses of Texas. But in Dallas they gave her red roses. And she’d thought, How funny—red roses. As is recounted elsewhere in our pages, after the doctors pronounced her husband dead, Jackie spent time with the body, and subsequently put her wedding ring on her husband’s finger.

THE SIXTH FLOOR MUSEUM/THE DALLAS MORNING NEWS/DALLAS TIMES HERALD COLLECTION/AP

In this photograph, Hurchel Jacks (at left, in the cowboy hat), who was Vice President Lyndon Baines Johnson’s driver in the motorcade, listens with others to news accounts on the car radio outside the Parkland Hospital emergency entrance. By this point, the whole world is frantically tuning in on radios and television sets, many people desperately unbelieving.

DALLAS TIMES HERALD/AP

Johnson, flanked by Secret Service agent Rufus Youngblood (left) and U.S. representative Homer Thornberry, leaves Parkland Hospital after the death of Kennedy and heads to Love Field airport.

CECIL STOUGHTON/THE WHITE HOUSE/GAMMA

The late President John F. Kennedy’s casket is brought onto Air Force One—aides and agents struggling with the nearly 600-pound load on narrow metal stairs—which will fly back to Andrews Air Force Base in Maryland from Dallas. The widow Jacqueline Kennedy stands amid members of JFK’s Irish American coterie—Larry O’Brien, Kenny O’Donnell and Dave Powers are there—in the crowd at the bottom of the steps. Kennedy’s staff, with the Secret Service assisting, have, essentially, spirited the body out of Parkland before a proper autopsy can be performed. There was even a scuffle inside the hospital between his staff and local officials over who had jurisdiction over Kennedy’s body.

CECIL STOUGHTON/CORBIS

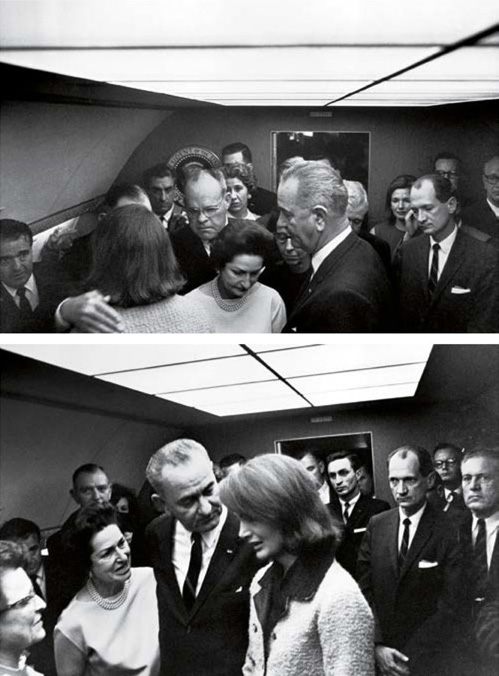

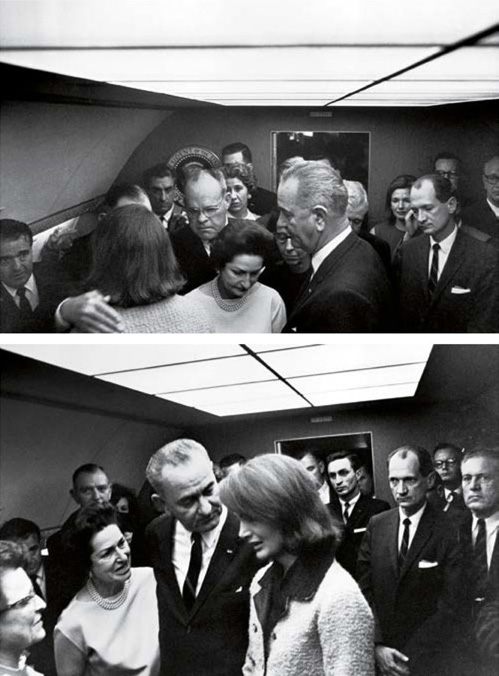

There is so much going on in this sequence of photographs by Cecil Stoughton. First, when Lyndon Johnson had been told about President Kennedy’s death at one p.m., he had been urged to return to Washington immediately in case there was a wider conspiracy functioning in Texas. The military placed the country on red alert. LBJ would not let Air Force One leave Dallas without Jacqueline Kennedy, and she wouldn’t board any plane without her husband’s body—and that’s where the arguing with the officials at Parkland over the autopsy, which the local and state authorities had a legal responsibility to perform, came in. Johnson was taken to the airport in advance, and eventually the Kennedy entourage, having forced the point, arrived, along with the casket. Several histories indicate that Jackie was reluctant to take part in the swearing in, but Johnson was ultimately persuasive. LBJ wanted a photo record of the moment and the transfer of power. The White House photographer Cecil Stoughton urged that a Dictaphone recording be made as well, and in the stateroom of the airplane—the largest open space in the cabin—Stoughton was forced, as he told the writer Trask, to “flatten himself against the rear bulkhead of the compartment” to make the shot.

He positioned Lady Bird Johnson and Jacqueline Kennedy on either side of President Johnson, and photographed over the shoulder of Federal Judge Sarah T. Hughes. The images were disseminated as quickly as humanly possible to show that the United States was moving forward in something approaching an orderly and democratic fashion.

CECIL STOUGHTON/GETTY

11/22/63

Washington, D.C.

UNIVERSAL HISTORY ARCHIVE/GETTY

An altogether extraordinary and unprecedented (and hopefully never to be repeated) scene rendered in these rarely seen photographs: The late President of the United States arriving back in Washington along with the newly inaugurated one—the 35th ceding to the 36th. In this photograph, Kennedy’s casket is brought to an ambulance at the airport.

BOB GOMEL

President Johnson and his wife arrive at the White House by helicopter. The autopsy on Kennedy’s body was executed between eight p.m. and roughly midnight, now Eastern time, at the end of this long and awful day, at the Bethesda Naval Hospital in Maryland by pathologists who didn’t even know that the tracheotomy performed earlier in Dallas had obliterated the exit wound. The rest has become part of a conspiratorial morass that has forever enshrouded the President’s murder—a topic discussed elsewhere in our book.

BETTMANN/CORBIS

Later, a military honor guard marches in front of the ambulance bearing the late President John F. Kennedy’s casket as it is returned to the White House, where it will lie in repose in the East Room, awaiting burial at Arlington National Cemetery.