Farewell

There would not be a funeral train as there had been with Abraham Lincoln and would be again with Bobby Kennedy. And yet the whole country came out and joined in, differently. There was television now, so there could be communal mourning. Parents explained to children what the images meant, and why the grandparents were crying. The Kennedy family stood tall and straight, though that surely took a mighty effort.

FEW EVENTS IN THE 20TH century—indeed, few in American history—were as universally experienced as the mourning for John F. Kennedy. The historian Martha Hodes has helped explain that, and a host of world citizens have testified to that fact. And now, here, these pictures from Washington, D.C., Arlington National Cemetery and elsewhere confirm what everyone knows: This was a seminal national moment.

But imagine, for a moment, what it was like on the inside—a grief no camera could capture. We all experienced the enormous tragedy as a stunning thing, but for the Kennedys it was the latest: This family simply could not escape the firm grip of fate. There were all the earlier disasters and adversities of the 1940s and ’50s, already recounted. Since the great success of the 1960 election, there had been Joe, who had worked so vigorously and at times ruthlessly to see his sons triumph, having so little time to savor Jack’s ascension before he had suffered a massive, disabling stroke that would leave him partially paralyzed if mentally lucid for the rest of his days. The grace of cognition would be its own curse: Before dying in 1969, Joe would bear near silent—but tear-stained—witness to the assassinations of two of his sons as well as the incident at Chappaquiddick and other sad events.

In August 1963, as we have briefly alluded to, Jackie gave birth to a second son, their fourth child by the family’s reckoning—many were unaware that Jackie had given birth to a stillborn baby, a girl named Arabella, in 1956. The 1963 baby, Patrick Bouvier Kennedy, was born prematurely with a respiratory disease and lived less than two days. At the funeral, the presiding prelate had had to coax the heartbroken President away from the tiny casket. And then: On November 22 of that same year, the sword of Damocles fell once more.

If, on the inside, this was the latest unfathomable affliction, on the outside this was the one we were compelled to share in. World leaders made their way to Washington; the man and woman in the street made their way to the Capitol rotunda. Everyone who couldn’t pay respects in person gathered with friends or family around the television. At the time, this was the first great shared funeral (it predated Winston Churchill’s by 14 months). Americans had been trained to come together for a space launch, and now there was this: We knew what to do, we knew how to enter the room. Also, the great advances in still photography had been achieved, and so we have a record unlike any other up to that point in historic time.

There is always one image, though. An entire war can be fought, and there is one image—or two or three or four—to symbolize it: a flag raised on Iwo Jima, a sailor kissing a nurse in Times Square. John F. Kennedy was killed, the entire world bade farewell, but we remember the President’s son, saluting along with the military escort. It is a beautiful and painful image. It is from the outside, and from the inside.

ELLIOTT ERWITT/MAGNUM

Upon landing at Andrews Air Force Base on November 22, President Johnson had asked for his countrymen’s help in leading the nation. One who quickly offers assistance is the Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower, who only three years earlier had occupied the Oval Office. Johnson chooses to walk in the funeral procession, a gesture for which the widow Jacqueline Kennedy will thank him in a handwritten note.

HENRY BURROUGHS/AP

Members of the White House staff file past the flag-draped coffin, in which the late President is lying in repose (as opposed to the public “lying in state”) in the East Room of the Executive Mansion for 24 hours before being transferred by horse-drawn caisson to the U.S. Capitol—proceeding, fittingly, through the daylong rain.

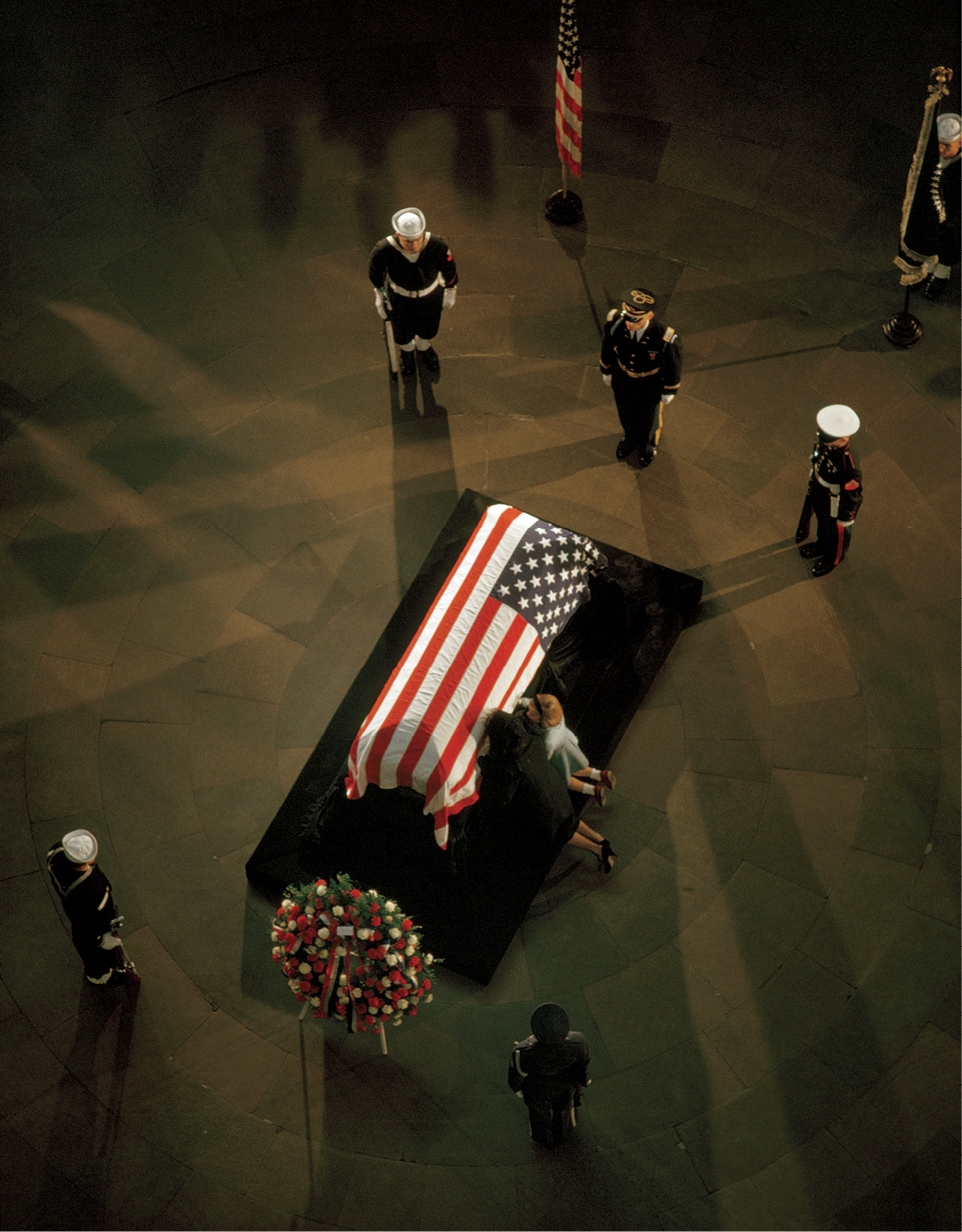

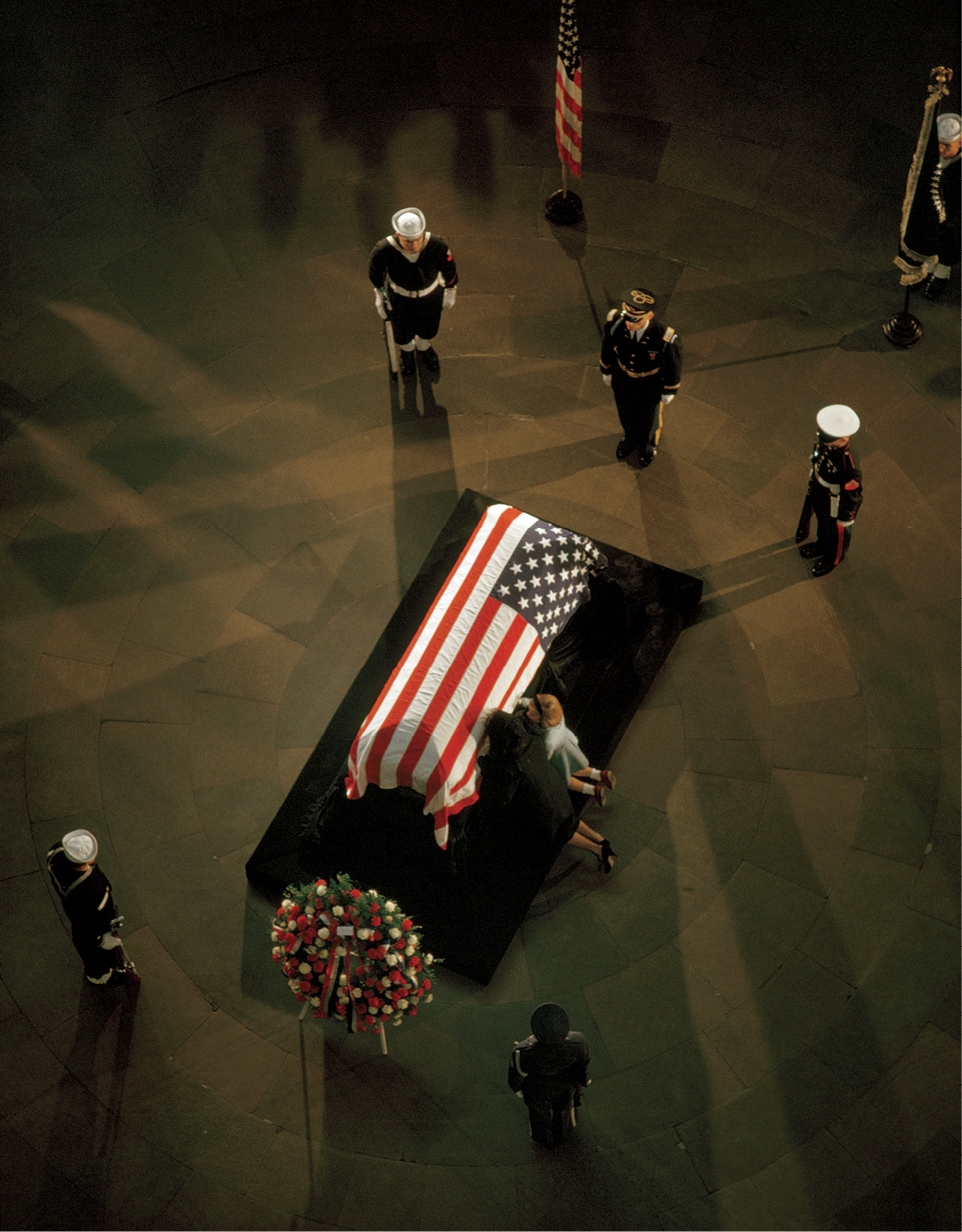

GEORGE F. MOBLEY/NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

In the Capitol rotunda, Jacqueline and Caroline Kennedy kneel and pray as the casket rests on the Lincoln Catafalque, upon which America’s first great martyr’s coffin had lain.

11/25/63

The Funeral Procession

HENRI DAUMAN

President Kennedy had been killed on a Friday; his state funeral in Washington would last the following three days. On Sunday, hundreds of thousands of Americans stood patiently in line, day and night, outside the U.S. Capitol, waiting a turn to file past the coffin and say farewell. Former Presidents Truman and Eisenhower had visited in the East Room, and now the citizenry came forth. On Monday morning there was a Requiem Mass at the Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle on Rhode Island Avenue, several blocks from the White House.

On the walk to St. Matthew’s cathedral from the White House, a stroll Jackie and Jack used to take when attending Sunday Mass, the President’s widow is accompanied on this day by (left to right) her brothers-in-law Stephen Smith (head down), Bobby Kennedy, Sargent Shriver (blue vest) and Ted Kennedy. More than 90 nations are represented by more than 200 dignitaries, including 19 heads of state at the Monday events, and Washington, so silent you can hear a pin drop, is as filled with witnesses as it might be for an inauguration.

BOB GOMEL

The caisson outside the church awaits the casket.

AP

Mrs. Kennedy enters the cathedral with Caroline and John Jr. to attend the Mass; Senator Edward M. Kennedy of Massachusetts trails behind.

BETTMANN/CORBIS

Outside St. Matthew’s cathedral, as the late President’s casket is placed upon the caisson, Jackie, just a moment earlier, has urged her son—whose third birthday is today, November 25—to salute his father, and the boy’s gesture is every bit as crisp as the color guard’s. In world history, there has never been a more visually indelible or heartbreaking salute.

BETTMANN/CORBIS

A sailor in the crowd of mourners is overcome. John F. Kennedy’s war service in the Navy permeates the state funeral: A sailor bears the presidential flag; the Navy Hymn, “Eternal Father, Strong to Save,” is played; separately, the Naval Academy Glee Club is enlisted for a requiem performance at the White House. An Army Special Forces unit has also been recruited by Robert F. Kennedy to attend the casket because Bobby knew of Jack’s particular interest in the special ops.

WALLY MCNAMEE/CORBIS

After the Mass at St. Matthew’s, the funeral cortege crosses the Memorial Bridge over the Potomac River to Arlington National Cemetery, where Kennedy will be buried. The riderless horse, Black Jack, symbolizes a fallen leader and trails the caisson carrying the casket—the same caisson that had borne the body of not only Franklin D. Roosevelt but also that of the Unknown Soldier.

AP

Meantime in New York City, a crowd assembles in Grand Central Terminal to watch a televised account of the proceedings. Some who were there remember that the great hall, with its cathedral-like vaulting and dim lighting, offered a proper, churchly atmosphere.

11/25/63

Burial

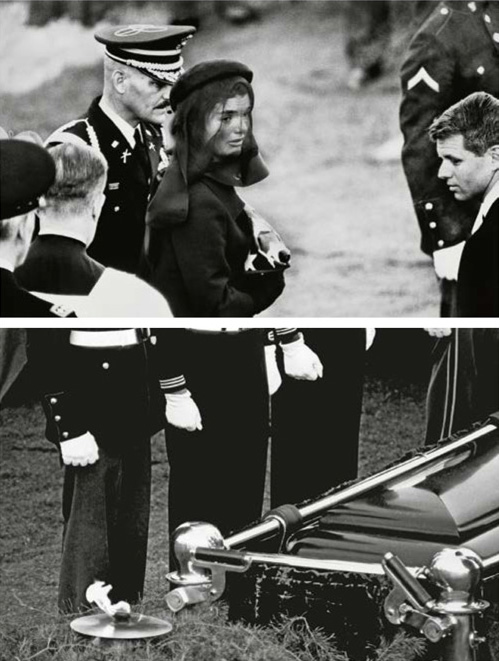

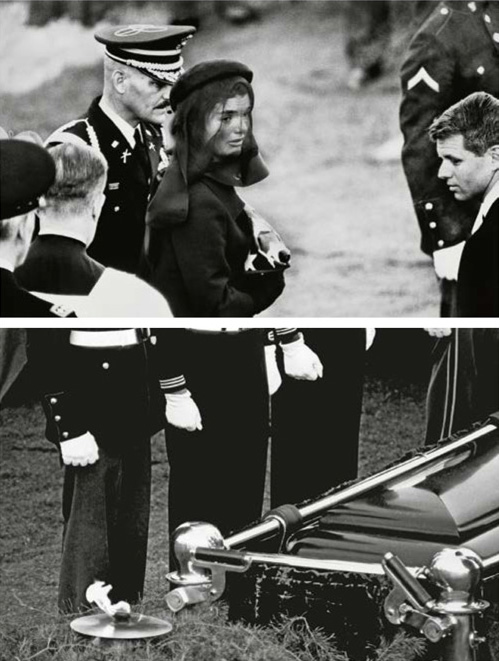

ELLIOTT ERWITT/MAGNUM

Three scenes from Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia, just outside the nation’s capital, where John F. Kennedy is buried on November 25 with full military honors: His widow, Jacqueline, and brother Bobby (top); the coffin about to be lowered (bottom); and servicemen standing guard over the flower-banked grave at dawn on the 26th, a white picket fence enclosing the area where the President is buried. Events of the long Monday, a national day of mourning as declared by President Johnson, are witnessed by perhaps a million people in Washington and, it is thought, nearly the entire remaining American population on television. (Coverage of events prior to the coffin being borne into the cathedral is transmitted to 23 additional countries, including the Soviet Union, via satellite.) The three major networks share 50 cameras, so that nothing—from the pipers of the Scottish Black Watch to the riderless horse to the minute movements of Mrs. Kennedy—is missed. Johnson has been urged by aides not to march in the funeral cortege, for safety’s sake, but he does so nonetheless, falling in behind the caisson. In his memoirs he will recall that, as he walked, “The muffled rumble of drums set up a heartbreaking echo.”

The limousine procession bearing foreign guests is so long from St. Matthew’s to Arlington that burial services begin before the last car arrives. The reason there are no pictures of the children at the graveside is because it had been determined by Jackie they were too young for that experience; they had said goodbye to their father shortly after John Jr.’s salute outside the church.

AP

Jackie herself lights the eternal flame that continues to burn at the grave, a flickering torchlight that meant so much to her during the remainder of her life (she died in 1994 at age 64), as she told the writer Theodore H. White. At 3:34 p.m. the casket is lowered into the ground.

As mentioned, the 25th was John Jr.’s third birthday. Two days later Caroline would turn six. Their party was postponed by their mother until December 5—the Kennedys’ last day in residence at the White House.