DAVID WOO/THE DALLAS MORNING NEWS

In a photograph from 2010, the strange shapes of one of the peristyles in Dealey Plaza, near where people scrambled or cowered after the shots rang out. Today, the structure gleams brightly in the sun.

Today in Dallas

Fifty years on, a desire to remember still wars with a desire to forget. GREGORY CURTIS has lived in Texas for many years; he recently returned to Dealey Plaza for our book and offers this essay. And then: a photographic portfolio of poignant reminders from The Sixth Floor Museum, photographed by Darren Braun for LIFE in April 2013.

OVER TIME I’VE HAD VARIOUS occasions to take visitors to the place in Dallas where President Kennedy was murdered. I always park several blocks away and then, without saying that I’m doing so, walk the route of the motorcade. We head west down Main Street, turn right onto Houston, and proceed toward the Texas School Book Depository, which stands at the next corner. If not for its place in history, this blocky, unremarkable building would have been torn down long ago. In fact the Depository is so bland that the visitor and I are usually at the corner of Houston and Elm waiting for the light to change before my visitor lets out a surprised, “Oh, my God! That’s it!” I watch as without fail the visitor’s eyes search out the sixth floor window where Oswald had his sniper’s nest and then go from there down to the street and then back up to the window again. And that’s when my visitor will says something like, “It’s not that far.”

No, it’s not. And although the trees are larger today than they were 50 years ago, their branches still don’t interfere with the line the fatal bullet took that day. I doubt that any busy corner in any American city has changed so little in the last half century. Anyone who has read or watched anything about the assassination finds the rest of the landscape by the Depository so familiar it can be eerie. Everything is still there more or less just as it was—Elm Street curving slightly downhill away from the Depository; the grassy knoll leading up to the white, cement pergola with its shafts and ledges; the stockade fence; the open space across Elm from the knoll; and the triple underpass a short way down the road. These landmarks all have their important places in the mythology that has grown up year after year around the assassination. You can even make your way behind the grassy knoll to the stockade fence, concealed behind trees, where some conspiracy theories have placed a second assassin. The wooden stockade is covered with poems, sayings, drawings and tributes—and not just for JFK; there are a few sympathetic phrases for Lee Harvey Oswald as well. Some of the slats are broken off, presumably by souvenir hunters. The fence looks authentic, but it’s not. The pickets have to be replaced every couple of years.

There is little else besides the graffiti to help the visitor know where he is—that he is, in fact, there. One small plaque in the ground says that this site has been commemorated by the federal government, but it doesn’t say what for. Some local folks think that kind of willful obfuscation is nonsense, and others think it’s for the best.

In front of the Depository and along both sides of Elm, there are usually knots of curious people poking around. They wander here and there taking photographs and pointing. Occasionally, though less often now than in the past, you can still see dogged conspiracy researchers bustling about importantly making measurements or lying on their backs to take a picture of the Depository from a particular spot at a particular angle. And then there are the hawkers selling grisly newsprint publications or books or DVDs about the assassination, complete with photographs of the autopsy. These blots on the landscape are generally loquacious, friendly men—sometimes a bit too friendly—whose tawdry presence around the Depository drives official Dallas crazy. The deans of this ragged group are Robert J. Groden and Don J. Miller. Since he arrived from the East Coast in 1995, Groden has been ticketed over 80 times for various minor offenses and has beaten every charge. Peaceful free speech and the right not to be harassed are his defense. On the other hand, Don J. Miller, who describes himself as a historian, has been coming to Dealey Plaza to sell his wares for as long as Groden and has never been ticketed. He says Groden, as an East Coaster, just doesn’t know how to handle the typical Dallas policeman.

Groden, Miller and their lesser rivals around Dealey Plaza are an annoyance to proper Dallas because they are a reminder of what Dallas feared the site would become: a cheap, sensational tourist attraction. Then again, Dallas might have worked against that with some kind of substantial monument. But that wasn’t going to happen, at least not out of doors. In the stunned aftershock of the event, Dallas was blamed for the assassination as much as Oswald was. The city leaders, a paternalistic and exclusive crowd in those days, knew that any hint that the city was trying to exploit this tragedy would doom the city’s reputation forever. They commissioned Philip Johnson to create a memorial to President Kennedy on a site a couple of blocks from the School Book Depository. Unfortunately, it turned out to be bare, passive and emotionless—as well as in the wrong place.

They were always able to squelch any dubious plans for Dealey Plaza itself. The Texas School Book Depository changed hands a few times until Dallas County acquired the building in 1977 and renovated the bottom five floors for county offices. The sixth and seventh floors were preserved, and this made some folks curious, even wary. They were transformed into a museum, which opened in 1989, and this upset some people. The old railroad yards next to the Depository were paved over to make part of it a parking lot, the only really substantial change in the appearance of the area since 1963.

Called simply The Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza, it presents the events of the President’s visit to Texas, the motorcade, the murder and the aftermath, clearly and without embellishment. There is also a savvy presentation of the cultural context of the early 1960s, an era that saw the appearance of music and literature that, like the assassination itself, remain important today: Silent Spring, The Fire Next Time, The Feminine Mystique, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and To Kill a Mockingbird. Oswald’s sniper’s nest is reconstructed exactly, although it’s protected by walls of glass. Interior walls enclose a small room where black-and-white newsreels of the funeral play continually. Some moments like the riderless horse with the boot stuck backward in its stirrup and young John Kennedy making his salute to his father’s casket stir the heart even after 50 years.

The seventh floor is also part of the museum. It’s simply a large, open space used for meetings, lectures and other events. Most of the time, however, it’s empty and a visitor can wander up there and stand solitary and uninterrupted at the corner window right above the sniper’s nest below on the sixth floor and look down, much as Oswald must have done, on Elm Street and the grassy knoll and the triple underpass. Even before November 1963, Dealey Plaza was an odd little corner of Dallas. Right on the western edge of downtown and near land that was used for the Dallas County Criminal Courts Building and other official structures, it was nevertheless unsuitable for development and historically subject to floods from the Trinity River, which flows through Dallas. But George B. Dealey, one of the leading citizens of early 20th-century Dallas, thought this area could become a stirring entranceway to the city and began buying parcels of land that he hoped would become a massive city park. The triple underpass was originally conceived as the gateway into that park, which would both awe and welcome visitors to Dallas. During the ’30s a reflecting pool, some planter boxes and the pergola got built, and in 1949 a statue of Dealey was erected looking inward toward Dallas rather than outward toward the west. But otherwise his project languished, perhaps from simple lack of interest. And in time, Dealey’s grand vision gradually transformed into a peculiarity. What was that reflecting pool doing on the edge of Dallas? Why was that odd pergola standing next to a warehouse full of schoolbooks? By November 1963, Dealey Plaza was just the visible remnant of a failed dream. For the Kennedy motorcade it was just a way of getting from here, Main Street, to there, the Trade Mart, where a luncheon would be held. After November 1963, Dealey Plaza became and still remains the unchanging setting for a tragedy of many, many other lost dreams. Almost hidden away, there is a museum, a very good one, that tells the stories.

GREGORY CURTIS, a native of Corpus Christi, Texas, and former editor of Texas Monthly magazine, is the author most recently of the book The Cave Painters.

DAVID WOO/THE DALLAS MORNING NEWS

In a photograph from 2010, the strange shapes of one of the peristyles in Dealey Plaza, near where people scrambled or cowered after the shots rang out. Today, the structure gleams brightly in the sun.

MIKE THEISS/NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

The X (above) does indicate where Kennedy’s car was when he was mortally wounded, but it is a highly unofficial marking, put in place and maintained by the people who work in the area as unaffiliated guides.

LARRY W. SMITH/EPA/CORBIS

In The Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza, the most poignant display is certainly the sniper’s nest, where Oswald took aim, recreated just as it was when the investigators found it.

Today in Dallas

Words Unsaid

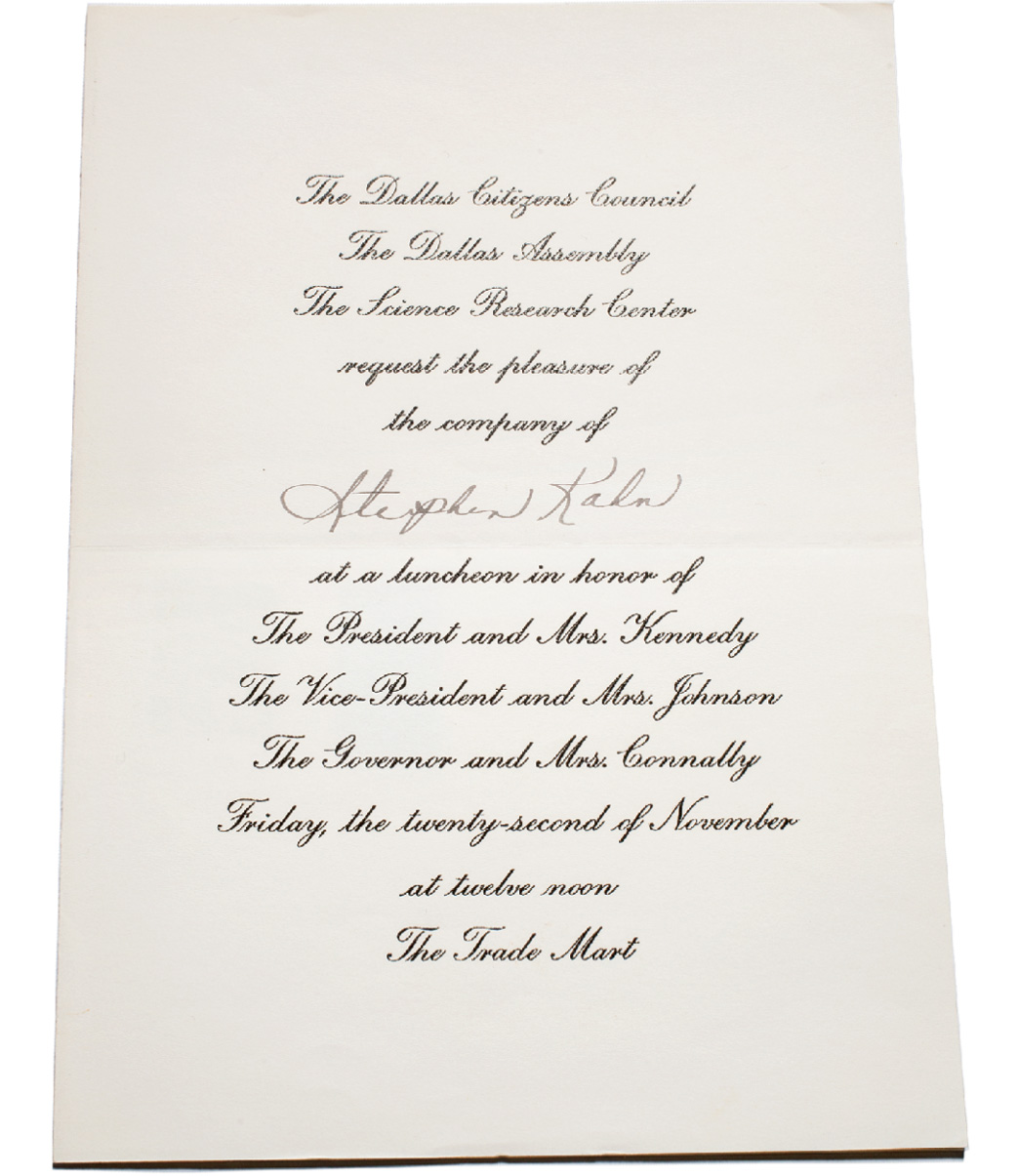

STEPHEN KAHN COLLECTION/COURTESY THE SIXTH FLOOR MUSEUM AT DEALEY PLAZA

Few museums in the world are as hushed as The Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza. Places that commemorate the Holocaust, certainly, and spaces in lower Manhattan preserving the memory of what happened on September 11, 2001. Exhibits in Normandy remembering D-Day.

Here, too, in The Sixth Floor Museum, everyone seems to realize the focus is on a tragic act. There is audio that takes us back to the day, and there are docents to explain things. But time and again, as you round a turn on your inevitable way to the sniper’s nest, you quietly come across something that gives you pause, or even makes you draw a deeper breath.

On these pages, items associated with the final appearance on the Dallas schedule—the lunch that didn’t happen. Above: Stephen Kahn and 2,599 others were invited to the event in the cavernous courtyard of the Trade Mart, where Kennedy was due to enjoy lunch and give a speech.

COURTESY HARLAN CROW FAMILY

The President’s unused place setting.

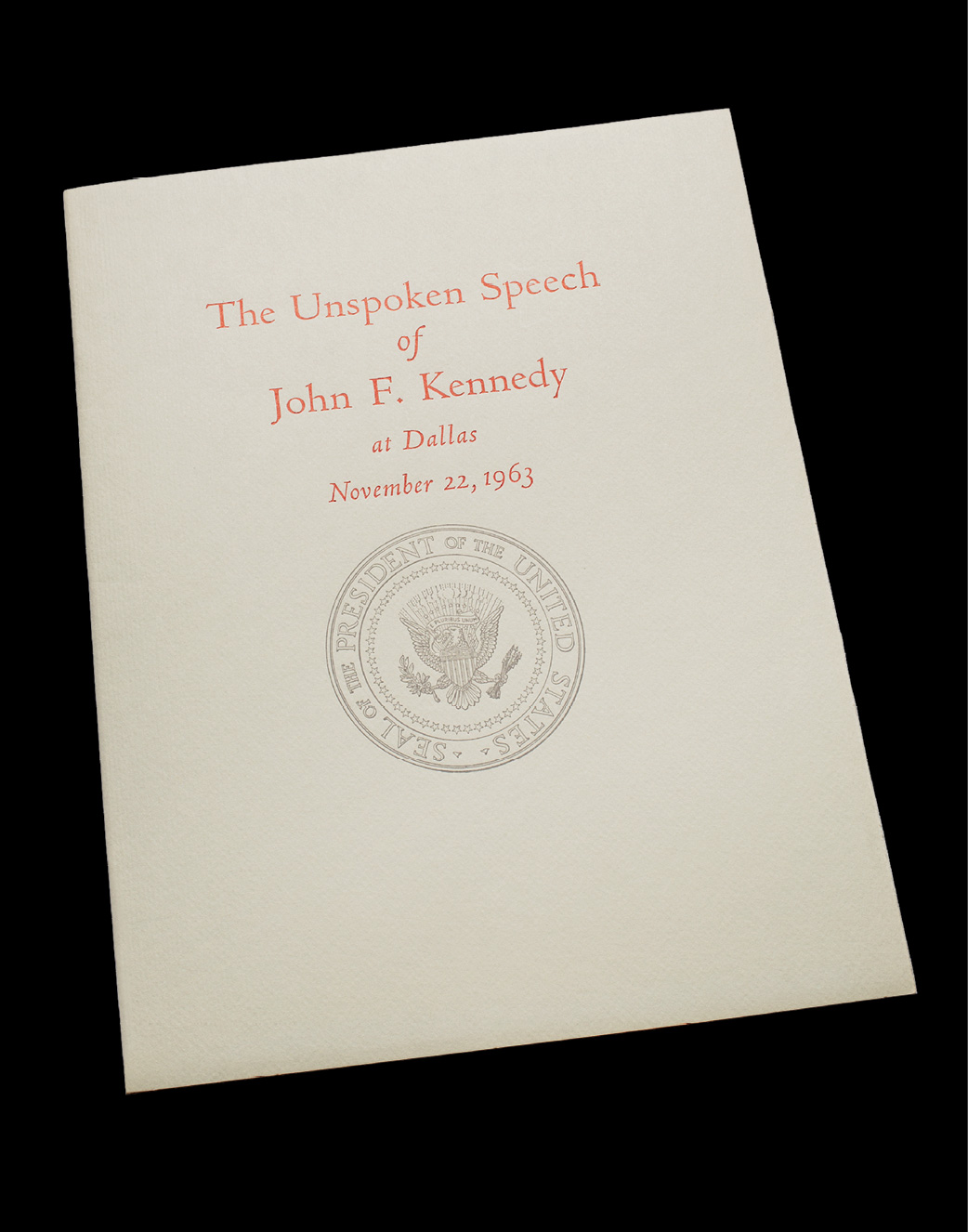

STANLEY MARCUS COLLECTION/COURTESY THE SIXTH FLOOR MUSEUM AT DEALEY PLAZA

His never-to-be-delivered remarks. Among the things he would have said: “There will always be dissident voices heard in the land, expressing opposition without alternatives, finding fault but never favor, perceiving gloom on every side and seeking influence without responsibility. Those voices are inevitable.

“But today other voices are heard in the land...”

Today in Dallas

Postmortems and Condolences

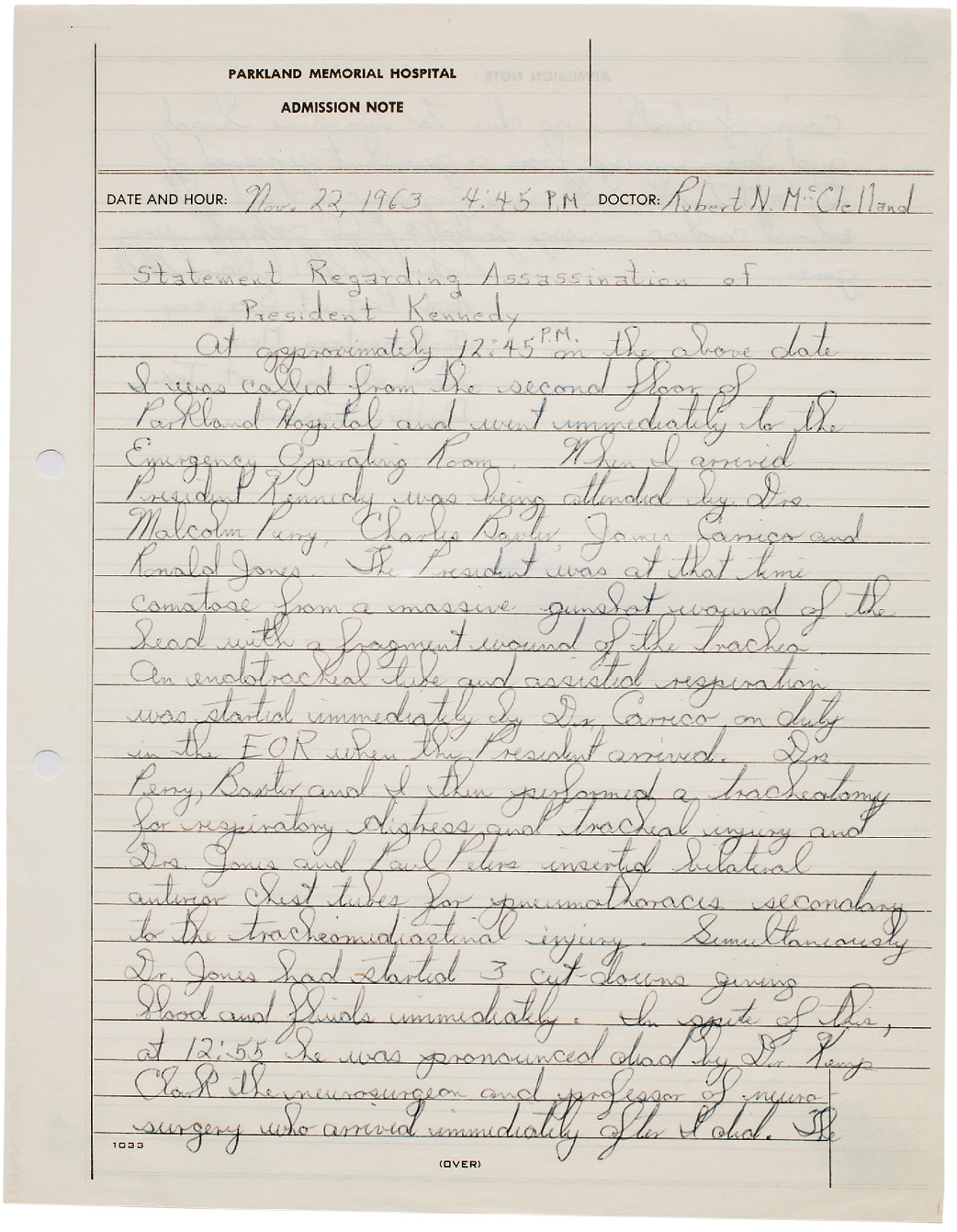

PARKLAND HOSPITAL COLLECTION/COURTESY THE SIXTH FLOOR MUSEUM AT DEALEY PLAZA

The afternoon had already been long when Dr. Robert N. McClelland, who had presided in Trauma Room One after Kennedy had been admitted to Parkland Memorial Hospital at 12:38 p.m., signed off on the Admission Note above. He and his colleague surgeons had known immediately upon examining the President that he was going to die. “[H]is head was...so greatly damaged,” McClelland later told the Warren Commission. After death was officially pronounced, all of the other drama that ensued at Parkland—the fight over the right to do the autopsy, the Kennedy faction’s successful scuffle for quick possession of the body—was all finished well before the Admission Note was clocked at 4:45; in fact the body was already being flown east. Back there would come the memorial services, the opening of thousands of letters of sympathy, the sending out of gracious notes of thanks in Jackie’s name (following page). It was over, except for the writing and remembering of it, things that continue a half century later.

From the Estate of Sanford Fox/Courtesy of the Sixth Floor Museum at Daley Plaza