yoga sutra 2.30

ahi sā-satya-asteya-brahmacarya-aparigrahā

sā-satya-asteya-brahmacarya-aparigrahā yamā

yamā

The five yama are Nonviolence, truthfulness, not-stealing, maintaining priorities and non-grasping

The yama are the first of the eight limbs of yoga (a

ā

ā ga), presented in the second chapter of the Yoga Sūtra. They are five attitudes, or (literally) restraints, suggested by Patañjali to free our relationships with others. Together, they create the conditions needed to establish a relationship and allow it to deepen in healthy ways by setting certain boundaries. Furthermore, they bring insights to relationships that take us towards a universal wisdom that goes beyond any specific relationship.

ga), presented in the second chapter of the Yoga Sūtra. They are five attitudes, or (literally) restraints, suggested by Patañjali to free our relationships with others. Together, they create the conditions needed to establish a relationship and allow it to deepen in healthy ways by setting certain boundaries. Furthermore, they bring insights to relationships that take us towards a universal wisdom that goes beyond any specific relationship.

Desikachar often emphasized that yoga is relationship, and that the measure of our yoga practice lies in the quality of our relationships with the people around us. As we have seen, inherent in the word “yoga” is the idea of the relationship between two separate principles. Such a relationship is profound and dynamic and respects the independence and fundamental differences between the two principles. This is a model that can also be applied to our interpersonal relationships where the two principles are ourselves and another person.

The yama are simply listed in YS 2.30. There follows an additional sūtra outlining the results as each yama is mastered and put into practice. Examining the fruits gives insight into what practicing each yama might require.

When approaching the yama from a Western cultural perspective, it is easy to see them as moral commands that make us “good” people. This can bring a sense of guilt or failure when we don’t act well, or a tendency towards denial about our shortcomings. The approach of the Yoga Sūtra is eminently practical: cultivating the yama leads us towards greater freedom and clarity in our relationships. Furthermore, the yama are just one of the limbs of yoga to be practiced, and “practice” itself implies that we are in training and therefore not perfect. Perfection is, in this sense, less of a state than a direction.

Yoga requires disciplined practice, deep reflection and humility; embodying the yama requires the same. Fundamentally, we all need to live our own yoga, and to relate to those around us, as honestly and authentically as possible.

The yama are conventionally presented as five attitudes or virtues to be adopted as ethical principles. They set boundaries on our behavior. We can think of them as radiating from our center towards others.

However, although it is true that the yama are qualities that we are trying to cultivate within ourselves, it is more helpful to understand them as applying to how we participate in our relationships.

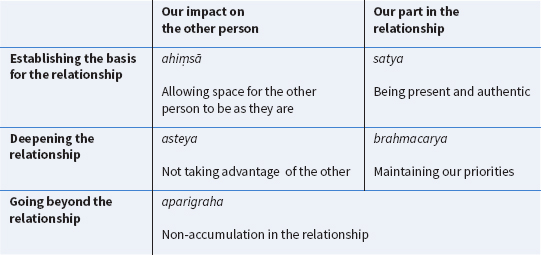

We can divide them into two pairs, with the fifth yama, non-grasping (aparigraha), as the fruit of the others. The first pair, nonviolence (ahi sā) and truthfulness (satya), establishes the basis of a relationship; ahi

sā) and truthfulness (satya), establishes the basis of a relationship; ahi sā concerns the space that we can offer another person, and satya our participation in the relationship. The second pair, not stealing (asteya) and maintaining our priorities (brahmacarya), explains how the relationship can deepen without becoming cluttered with unnecessary baggage. Here, also, asteya is more concerned with the other person and brahmacarya more with our participation. The last term, aparigraha, allows us to go deeper in order to discover truths that take us beyond any individual relationship.

sā concerns the space that we can offer another person, and satya our participation in the relationship. The second pair, not stealing (asteya) and maintaining our priorities (brahmacarya), explains how the relationship can deepen without becoming cluttered with unnecessary baggage. Here, also, asteya is more concerned with the other person and brahmacarya more with our participation. The last term, aparigraha, allows us to go deeper in order to discover truths that take us beyond any individual relationship.

In this way, we can further define the yama as follows:

sā and satya

sā and satya

yoga sutra 2.35

ahi sā-prati

sā-prati

hāyā

hāyā tat-sannidhau vaira-tyāga

tat-sannidhau vaira-tyāga

In the presence of one established in nonviolence, hostility diminishes

Ahi sā is literally “Nonviolence” and is common to all the spiritual disciplines of India (and indeed the world). As the first yama, ahi

sā is literally “Nonviolence” and is common to all the spiritual disciplines of India (and indeed the world). As the first yama, ahi sā is considered to be the foundation of the others—the rest should all be consistent with it and qualified by it. In some commentaries, the other yama are considered to be simply ways of strengthening and purifying ahi

sā is considered to be the foundation of the others—the rest should all be consistent with it and qualified by it. In some commentaries, the other yama are considered to be simply ways of strengthening and purifying ahi sā within us. Ahi

sā within us. Ahi sā is practiced at the levels of body, speech and mind. In other words, it is not only about physical action, but also how we communicate with, and even how we think about, another person.

sā is practiced at the levels of body, speech and mind. In other words, it is not only about physical action, but also how we communicate with, and even how we think about, another person.

In YS 2.35, it is said that hostility is abandoned in the vicinity of one who has mastered ahi sā. If your personal space is threatened, it is easy to become defensive; if there is no perceived threat, there is no need to be defensive. In light of YS 2.35, we could reframe ahi

sā. If your personal space is threatened, it is easy to become defensive; if there is no perceived threat, there is no need to be defensive. In light of YS 2.35, we could reframe ahi sā as concerning the space that we offer the other person such that the impulse to be defensive does not arise. Nonviolence in this sense means creating the conditions within a relationship for the other to simply be as they are, fully accepted and valued, with no desire on our part to change them. So often in relationships, particularly as they become more established or involve loved ones, it is easy for the agenda of change to creep in: “If only he/she would be more . . .” If we understand ahi

sā as concerning the space that we offer the other person such that the impulse to be defensive does not arise. Nonviolence in this sense means creating the conditions within a relationship for the other to simply be as they are, fully accepted and valued, with no desire on our part to change them. So often in relationships, particularly as they become more established or involve loved ones, it is easy for the agenda of change to creep in: “If only he/she would be more . . .” If we understand ahi sā in this way its scope is expanded. Nonviolence in a physical sense may be relatively easy to observe in our culture, but offering a nonjudgmental space of acceptance to others is a constant challenge.

sā in this way its scope is expanded. Nonviolence in a physical sense may be relatively easy to observe in our culture, but offering a nonjudgmental space of acceptance to others is a constant challenge.

A relationship of yoga implies space; sa yoga implies lack of space. We cannot practice ahi

yoga implies lack of space. We cannot practice ahi sā without giving the other both the space to communicate and the privilege of being heard. If we cannot offer another these, how can there be a genuine relationship?1 The great peacemakers of history have always been willing to give their adversaries the space to be heard without feeling judged or threatened. In such a space, it is easy to let go of hostility and this forms the basis for real dialogue and the possibility of lasting peace. There are also many stories of yogis who lived in the forests and around whom wild creatures displayed no fear. Whether we call this an aura, “vibe” or simply the atmosphere, animals seem intuitively sensitive to the quality of the space that surrounds individuals, just as the air seems charged with aggression that emanates from an angry or violent person.

sā without giving the other both the space to communicate and the privilege of being heard. If we cannot offer another these, how can there be a genuine relationship?1 The great peacemakers of history have always been willing to give their adversaries the space to be heard without feeling judged or threatened. In such a space, it is easy to let go of hostility and this forms the basis for real dialogue and the possibility of lasting peace. There are also many stories of yogis who lived in the forests and around whom wild creatures displayed no fear. Whether we call this an aura, “vibe” or simply the atmosphere, animals seem intuitively sensitive to the quality of the space that surrounds individuals, just as the air seems charged with aggression that emanates from an angry or violent person.

Hi sā (violence, the opposite of ahi

sā (violence, the opposite of ahi sā) begins with negative judgments about people. These often surface before any real contact or communication has taken place. Noticing the assumptions and judgments we make about people can be the starting point in developing a more open and accepting attitude to the world.

sā) begins with negative judgments about people. These often surface before any real contact or communication has taken place. Noticing the assumptions and judgments we make about people can be the starting point in developing a more open and accepting attitude to the world.

yoga sutra 2.36

satya-prati

hāyā

hāyā kriyā-phala āśrayatvam

kriyā-phala āśrayatvam

When established in truthfulness, words and actions are consistent

Next, we come to satya, related to the Sanskrit term sat, meaning “that which is real.” Satya is communication that reflects what is real or true, and is genuine and authentic. If ahi sā concerns the space that we can offer another in a relationship, satya is about the space that we occupy and the quality of the presence that we ourselves offer. Satya is concerned with our authenticity in the relationship, in being present, engaged and honest in our communication.

sā concerns the space that we can offer another in a relationship, satya is about the space that we occupy and the quality of the presence that we ourselves offer. Satya is concerned with our authenticity in the relationship, in being present, engaged and honest in our communication.

The first step in this is to be present, to put something of ourselves into the relationship, rather than hide behind some convenient mask. The second step is to communicate our truth rather than take refuge in superficial pleasantries. This is about authenticity, where there is congruence between our being and what we express. In stating our truth, however, there are limits. In counseling, we talk about “appropriate transparency”: that is, communicating honestly but bounded by a measure of appropriateness. What is this level of appropriateness? The Mahābhārata says, “Speak the truth which is pleasant. Do not speak unpleasant truths. Do not lie, even if the lies are pleasing to the ear.” Satya, in other words, is always tempered by ahi sā and should never arise from anger, frustration or a wish to harm the other person.

sā and should never arise from anger, frustration or a wish to harm the other person.

We should also remember that our truth is not necessarily the Truth. The B hadāra

hadāra yaka Upani

yaka Upani ad breaks down the word into three parts: sa, ti and ya: “The first and last syllables are the truth. In the middle is untruth. This untruth is enclosed on both sides by truth; thus truth prevails. Untruth does not hurt him who knows this.”2 In other words, our own partial or relative truth—truth with a small “t” if you like—is part of and contained by the larger, universal Truth. In the Yoga Sūtra this “eternal truth” is called

ad breaks down the word into three parts: sa, ti and ya: “The first and last syllables are the truth. In the middle is untruth. This untruth is enclosed on both sides by truth; thus truth prevails. Untruth does not hurt him who knows this.”2 In other words, our own partial or relative truth—truth with a small “t” if you like—is part of and contained by the larger, universal Truth. In the Yoga Sūtra this “eternal truth” is called  ta. In a practical sense, ahi

ta. In a practical sense, ahi sā and satya provide mutual limits to the empathic space that we can offer to another and the appropriately transparent expression of our truth.

sā and satya provide mutual limits to the empathic space that we can offer to another and the appropriately transparent expression of our truth.

When we express ourselves truthfully and appropriately, there is an energetic power to which those around us and the world itself seem to respond. YS 2.36 states that when we are established in satya, there is a positive correspondence between our actions and their intended consequences. It is as if our words and actions have power because they reflect something inherently true. Those around us recognize this and respond accordingly.

The space of ahi sā invites the other to feel accepted, their communication truly heard, with no need for defensiveness. The space of satya invites us to be authentically present and to communicate honestly and transparently, within the limits set by the principles of ahi

sā invites the other to feel accepted, their communication truly heard, with no need for defensiveness. The space of satya invites us to be authentically present and to communicate honestly and transparently, within the limits set by the principles of ahi sā and satya themselves. In such circumstances, the relationship may deepen, and the next pair of yama become more acutely relevant.

sā and satya themselves. In such circumstances, the relationship may deepen, and the next pair of yama become more acutely relevant.

yoga sutra 2.37

asteya-prati

hāyā

hāyā sarva-ratna upasthānam

sarva-ratna upasthānam

When established in not stealing, many treasures arise

As time passes in any relationship, things get more complicated. Perhaps we get to know someone better, we know more about their lives, and our interaction may become increasingly habitual. In couples, individuals can lose their independent identity outside of the relationship. What may have started as a relationship with clear boundaries, such as a working or professional relationship, can easily begin to overflow into other areas. Subtly, people can begin to manipulate or take advantage of one another, even if this happens on an entirely unconscious level. Familiarity, as the saying goes, often breeds contempt.

If we are not careful, we can become increasingly enmeshed and the relationship loses its vitality as its original purpose becomes compromised. This is a classic example of sa yoga, where a relationship becomes confused and there is a loss of freedom. Asteya and brahmacarya become increasingly relevant as an antidote to the potential for this sa

yoga, where a relationship becomes confused and there is a loss of freedom. Asteya and brahmacarya become increasingly relevant as an antidote to the potential for this sa yoga.

yoga.

Asteya is literally “non-stealing.” This has an obvious meaning in not stealing physical objects. But we must also consider the many ways we can take from another person what is rightly theirs: how we might steal their attention, their ideas, and even profit unfairly from their company and association.

Asteya may be understood as “not taking advantage of the other.” It is a development of ahi sā and particularly comes to bear as a relationship deepens. Like ahi

sā and particularly comes to bear as a relationship deepens. Like ahi sā, it is concerned with the quality of the space that we offer the other person in a relationship, a space in which they are not exploited or used in any way. According to the Yoga Sūtra, if we can really embrace asteya we will receive “treasures.” The metaphor of treasure, or precious gems (ratna), is commonly used in Indian philosophy to indicate the richness of life. So, in fact, through embracing asteya we have the possibility of receiving so much more—something that touches life itself, rich and fresh: the product of open and free interaction rather than of grasping and manipulation.

sā, it is concerned with the quality of the space that we offer the other person in a relationship, a space in which they are not exploited or used in any way. According to the Yoga Sūtra, if we can really embrace asteya we will receive “treasures.” The metaphor of treasure, or precious gems (ratna), is commonly used in Indian philosophy to indicate the richness of life. So, in fact, through embracing asteya we have the possibility of receiving so much more—something that touches life itself, rich and fresh: the product of open and free interaction rather than of grasping and manipulation.

yoga sutra 2.38

brahmacarya-prati

hāyā

hāyā vīrya-lābha

vīrya-lābha

For one who maintains priorities, tremendous energy develops

As the twin of asteya, brahmacarya is concerned with how we maintain our focus in the relationship as it develops. We understand brahmacarya as “not losing our priorities” in the relationship. Literally translated, brahmacarya means traveling towards brahma, the highest truth, reality or God.

In a traditional context, brahmacarya was a stage of life where young people studied the highest truths intensively with a teacher before they married and began family life. For monastic orders, the stage of brahmacarya was maintained throughout life. The focus in brahmacarya is realizing the highest truth, and thus avoiding any distractions or loss of vitality. The most powerful distraction and loss of vitality was considered to arise through sexual activity and hence brahmacarya became associated with sexual restraint and often celibacy. The spirit of brahmacarya is literally about moving towards the highest truth or, in a more general context, maintaining boundaries so that one does not lose sight of one's goal.

“The focus in brahmacarya is realizing the highest truth, and thus avoiding any distractions or loss of vitality.”

Over time, it is easy to find oneself drawn into aspects of a relationship that were not anticipated which can easily become distractions. Sometimes, they may be welcome and appropriate, but often they divert our focus and dissipate our energy.

In a similar way to asteya, failure to respect brahmacarya can lead to the space and clarity of the relationship becoming compromised. Particularly in professional relationships, such as with work colleagues or in teaching or therapeutic roles, the blurring of boundaries can have serious consequences.

Even for someone established in the other yama, they may find themselves manipulated, tempted or coerced into territory that is inappropriate or undesirable in a relationship. In such circumstances, restraint and discipline are needed to maintain appropriate boundaries. For the yoga teacher, Desikachar had some straightforward advice: “When teaching yoga, stick to yoga.”3

In any situation where we begin to become overwhelmed or consumed beyond what is appropriate (for example, becoming obsessed with our work), we could say that there is an issue with brahmacarya. The fruit of being established in brahmacarya is vitality and vigor. Brahmacarya helps us to channel our energy and prevents us from dissipating it unwisely. Whenever we feel low in energy, it would be advisable to consider brahmacarya, asking ourselves what are our priorities, what is dissipating our energy, and what boundaries need to be put in place or strengthened to protect ourselves.

Even in the West where attitudes towards sexuality may be very different from the traditional Indian context, we would still be wise to recognize the power of our sexual energy and the ways in which it may support us or be abused. This has been the downfall of many spiritual teachers.

yoga sutra 2.39

aparigraha-sthairye janma-katha tā-sa

tā-sa bodha

bodha

When non-grasping is established, the mysteries of life are revealed

Aparigraha means “non-grasping” or “non-possession.” At first glance, this might seem synonymous with non-stealing, but the scope of each is quite different. Aparigraha concerns the ability to keep a relationship fresh and uncluttered in a much more general sense. It recognizes our tendency to allow a relationship to accumulate baggage over time, so that it becomes increasingly defined by what has come before. This is a natural tendency in all relationships, but it fundamentally limits our vitality and freedom. Aparigraha is the ultimate antidote for sa yoga in relationships. As the last of the yama, it occupies a special place and has a profound significance.

yoga in relationships. As the last of the yama, it occupies a special place and has a profound significance.

Practicing aparigraha involves meeting a relationship consistently as if for the first time, letting go of expectations, prejudices and habitual patterns accumulated from the past. In the words of Peter Hersnack, “don't make your relationship into a photo album,”4 where memories invite constant expectation, comparison and disappointment.

“Nongrasping” involves letting go of what has been and living in the present. Aparigraha is related to vairāgya, and like vairāgya can be misunderstood in a way that limits, rather than opens us. Letting go and detaching can easily become an avoidance technique. We are detached, so nothing touches us; we don't hold on to anything, so we don't really care about anything and nothing really matters. Genuine aparigraha is none of these. We are present and open to the possibilities of the moment, in a way that allows us to feel and experience fully, but with sensitivity and respect for the other yama out of which it arises. It allows us to experience the full richness of life.

The fruit of aparigraha is one of the more curious claims of the Yoga Sūtra: by becoming established in aparigraha there is an awakening to the “how-ness of life” (janma-katha tā).5 This suggests that embodying aparigraha brings insight into the nature of life itself. This is universal and transcends any specific relationship. It opens our eyes to a universal truth that touches something of the mystery of life. The key to understanding this is to return to the fundamental principles of the yoga worldview—the relationship between spirit and matter: a mysterious relationship that gives rise to life and vitality within us (prā

tā).5 This suggests that embodying aparigraha brings insight into the nature of life itself. This is universal and transcends any specific relationship. It opens our eyes to a universal truth that touches something of the mystery of life. The key to understanding this is to return to the fundamental principles of the yoga worldview—the relationship between spirit and matter: a mysterious relationship that gives rise to life and vitality within us (prā a). When we live this relationship creatively, we are energized: engaged in life, but also in some sense always free. When we misidentify with this energy of life, crystallizing our hopes, fears, and sense of identity in an unhealthy way, we can become increasingly stuck. We also lose the ability to respond creatively to the changes and challenges that life presents.

a). When we live this relationship creatively, we are energized: engaged in life, but also in some sense always free. When we misidentify with this energy of life, crystallizing our hopes, fears, and sense of identity in an unhealthy way, we can become increasingly stuck. We also lose the ability to respond creatively to the changes and challenges that life presents.

āyāma of relationships”

āyāma of relationships”An important principle in yoga is the cultivation of the free flow of prā a, vital energy. Prā

a, vital energy. Prā a flows within the body governing all physiological and psychological processes, but also circulates outside the body in our perception and interaction with the world around us. As we have seen, in Ha

a flows within the body governing all physiological and psychological processes, but also circulates outside the body in our perception and interaction with the world around us. As we have seen, in Ha ha Yoga, prā

ha Yoga, prā āyāma is understood as a process by which blockages and restrictions in the body can be removed from the system of energetic channels called nā

āyāma is understood as a process by which blockages and restrictions in the body can be removed from the system of energetic channels called nā ī. The free circulation of prā

ī. The free circulation of prā a brings vitality, clear perception and stability of mind. Blockages in the system create illness, psychological issues and ignorance. Clearing the central channel by removing the fundamental blockage at its base, allowing prā

a brings vitality, clear perception and stability of mind. Blockages in the system create illness, psychological issues and ignorance. Clearing the central channel by removing the fundamental blockage at its base, allowing prā a to flow where normally it does not, is associated with profound wisdom and deep absorption.6

a to flow where normally it does not, is associated with profound wisdom and deep absorption.6

Relationships are also channels through which there is energetic interaction—and yama can be understood as the “prā āyāma of relationships.” Often, we create blockages which accumulate over time. The energy in such relationships becomes increasingly stuck and stagnant, and these relationships become subject to projection, manipulation and distortion. The yama, like prā

āyāma of relationships.” Often, we create blockages which accumulate over time. The energy in such relationships becomes increasingly stuck and stagnant, and these relationships become subject to projection, manipulation and distortion. The yama, like prā āyāma, help to free up the energetic channels and to keep them clear, so that the energy of a relationship (which is also seen as prā

āyāma, help to free up the energetic channels and to keep them clear, so that the energy of a relationship (which is also seen as prā a) can circulate freely, remaining vibrant and alive. Mastering aparigraha is like clearing the central channel in that it unlocks a far wider scope of experience and vitality.

a) can circulate freely, remaining vibrant and alive. Mastering aparigraha is like clearing the central channel in that it unlocks a far wider scope of experience and vitality.

In prā āyāma, unblocking the central nā

āyāma, unblocking the central nā ī requires considerable preparation; in a similar way, aparigraha arises as the fruit of the other yama. As the final yama, aparigraha allows us to establish freedom in all our relationships and for these relationships to remain vital and fresh as they develop. It is like the “magic key” that unlocks our experience of life. We should never forget that aparigraha, along with the other yama, is something that must be practiced. Understanding the yama can help, but only inasmuch as they inform our practice, a practice that must extend way beyond the confines of the mat to touch all areas of our lives, and help us to live more creatively and vibrantly.

ī requires considerable preparation; in a similar way, aparigraha arises as the fruit of the other yama. As the final yama, aparigraha allows us to establish freedom in all our relationships and for these relationships to remain vital and fresh as they develop. It is like the “magic key” that unlocks our experience of life. We should never forget that aparigraha, along with the other yama, is something that must be practiced. Understanding the yama can help, but only inasmuch as they inform our practice, a practice that must extend way beyond the confines of the mat to touch all areas of our lives, and help us to live more creatively and vibrantly.

Sādhana: Countering negative tendencies

yoga sutra 2.31

jāti-deśa-kāla-samaya-anavacchinnā sārva-bhaumā

sārva-bhaumā mahā-vratam

mahā-vratam

When yama are observed in all circumstances, irrespective of birth, place or time, it is like a Great Vow

Cultivating yama, and perhaps more importantly, addressing the negative tendencies that run counter to them, is a big challenge. In his commentary, Vyāsa acknowledges that under normal circumstances, observance of yama is conditional upon our livelihood and culture. A fisherman, for example, cannot observe ahi sā towards the fish that he catches and kills. Similarly, there are extreme situations that call for responses that contravene the yama.

sā towards the fish that he catches and kills. Similarly, there are extreme situations that call for responses that contravene the yama.

However, if the yama are observed in all conditions irrespective of our livelihood, culture or situation, this is considered a mahāvratam: a great vow, and a serious undertaking. This is a pathway only for the serious yogi; for most of us, however, it remains an ideal which can inspire us within the realities of our lives.

We should remember that in yoga and Indian philosophy in general, guidelines for conduct such as the yama are not simply about being good and morally superior. Nor are yama a selfish undertaking—they encourage relationships that are positive for all involved. It is also important to emphasize that yama are not imposed for their own sake, but because they are helpful in maintaining our clarity and peace of mind. They are designed to keep matters straightforward, reflecting the truth of how things are and to eliminate negative consequences of our thoughts and actions. The enlightened being does not have to practice yama: it is how they naturally are. For us mere mortals, however, very much on the path of practice, yama and the reduction of their opposite tendencies is something that we need to actively cultivate. But, as “trainees,” we should have compassion towards ourselves and others when we struggle or fail.

yoga sutra 2.33

vitarka-bādhane pratipak a-bhāvanam

a-bhāvanam

When we are trapped by (disturbing) thoughts, we can cultivate a different perspective

The Yoga Sūtra suggests a fundamental approach to working with thoughts that run counter to the yama, particularly when we feel stuck with such thoughts. The first stage is to recognize them, but even then, it is not always easy to stop them. It is as if they have their own energy, and reinforce each other, even if we want them to stop. This is the sense in which we can feel oppressed or trapped by our negative thoughts and feelings.

In such cases, we work with pratipak a bhāvana, literally: “cultivating the other wing.” We find a way to see things differently by deliberately cultivating thoughts or feelings opposite to those that are troubling us. It can also be helpful to remind ourselves of the consequences of negative thoughts and behavior. At the heart of the method lies a simple truth: we are creatures of habit, even in our emotional and psychological lives. We tend to live through repeated patterns of thought, feeling and behavior. By deliberately cultivating a different feeling, we are both undermining the existing habit and seeking to create a stronger positive one.

a bhāvana, literally: “cultivating the other wing.” We find a way to see things differently by deliberately cultivating thoughts or feelings opposite to those that are troubling us. It can also be helpful to remind ourselves of the consequences of negative thoughts and behavior. At the heart of the method lies a simple truth: we are creatures of habit, even in our emotional and psychological lives. We tend to live through repeated patterns of thought, feeling and behavior. By deliberately cultivating a different feeling, we are both undermining the existing habit and seeking to create a stronger positive one.

Thus, when we experience thoughts and feelings that run counter to the yama, we should cultivate alternatives which are more helpful. There are many ways that we can practice pratipak a bhāvana; for example, we might formally sit in meditation and imagine a problematic relationship. Then we may consciously generate positive feelings towards the other person that are consistent with the spirit of yama.

a bhāvana; for example, we might formally sit in meditation and imagine a problematic relationship. Then we may consciously generate positive feelings towards the other person that are consistent with the spirit of yama.

Another way to understand pratipak a bhāvana is to change our point of view. We might imagine relating to the other person from a neutral perspective, outside of the relationship. Or, we might imagine the situation from their point of view, as if we were walking in their shoes. These both take us out of our habitual orbits and enable a fresh perspective.

a bhāvana is to change our point of view. We might imagine relating to the other person from a neutral perspective, outside of the relationship. Or, we might imagine the situation from their point of view, as if we were walking in their shoes. These both take us out of our habitual orbits and enable a fresh perspective.

We might also differentiate between the facts of a situation and our story about it. The story is our own construction, and thus it is possible to change it: we could make a conscious effort to “reframe our story.” By understanding a situation in a new way, a new space for perception is cleared.

yoga sutra 2.34

vitarkā hi

hi sā-ādaya

sā-ādaya k

k ta-kārita-anumoditā

ta-kārita-anumoditā lobha-krodha-moha-pūrvakā

lobha-krodha-moha-pūrvakā m

m du-madhya-adhimātrā

du-madhya-adhimātrā du

du kha-ajñāna ananta-phalā

kha-ajñāna ananta-phalā iti pratipak

iti pratipak a-bhāvanam

a-bhāvanam

Disturbing thoughts, arising from desire, anger or delusion, whether acted upon or tacit, and of whatever intensity, will result in endless suffering and confusion. So: cultivate alternative perspectives

The Yoga Sūtra emphasizes the negative effects that accumulate when we indulge emotions that run contrary to yama. These are said to be du kha, personal suffering and a sense of dissatisfaction, and ajñāna, misunderstanding and confusion. It is in our own interests to practice the yama as a means to reduce distress and suffering in our relationships, and to live with greater clarity. Patañjali also identifies the root negative emotions that violate the yama: lobha (desire), krodha (anger), and moha (delusion). When these predominate, our actions cause distress and misunderstanding. By taking small steps to live in accordance with the yama, we work towards reducing such negative consequences. The more we can embrace the yama, the freer we become. No effort is wasted.

kha, personal suffering and a sense of dissatisfaction, and ajñāna, misunderstanding and confusion. It is in our own interests to practice the yama as a means to reduce distress and suffering in our relationships, and to live with greater clarity. Patañjali also identifies the root negative emotions that violate the yama: lobha (desire), krodha (anger), and moha (delusion). When these predominate, our actions cause distress and misunderstanding. By taking small steps to live in accordance with the yama, we work towards reducing such negative consequences. The more we can embrace the yama, the freer we become. No effort is wasted.