The engine is Spring, the fuel is beauty. All of those resolutions promised in the sleepy grip of New Year’s wintery fug can now be realized, because we have a new gear to throttle forward into.

There are all kinds of budding and blossoming and buzzing happening everywhere. Birds, animals and plants unfurl, unfold and burst into life. Look at it all:

- • swallows and herons and wrens and skylarks

- • toads and adders and lambs and butterflies

- • daffodils and primroses and crocuses and violets

- • wild garlic and hawthorn

and lovely lovely snowdrops, which always indicate the return of Spring. ‘Our Lady of February’ the early Catholics called them in monastery gardens. My granny called them ‘Fair Maids of February’. I call them snowdrops.

The grass is just that bit greener, the blue sky is proper BIG blue, all the colours gather strength, and the wonderful light just promises EVERYTHING, doesn’t it? Somehow it’s so … hopeful. It’s all a bit sexy. Even the toads. No wonder there’s a Spring in our step!

More and more as I grow older, I come to realize that we are bound to the seasons in so many ways. Even climate change hasn’t altered that in any significant way. Yet.

Being aware that so many seasons have ebbed and flowed ages before us, and will continue to do so ages after us, serves to remind us how held we are by them, how inevitable they are. How quickly time trickles past.

Our lives are really seasons too, in the bigger sense. Our lifespan chimes with them. Spring is the first twenty-five years, Summer is twenty-five to fifty years, Autumn is fifty to seventy-five years and Winter is seventy-five to … well … the end, the forever end.

So, Spring is the beginning really, the birth, the very start of life. From babyhood, through infancy, that whole first lap into our mid-twenties, such a hugely formative part of our story. This is the abundant time. When life gives us so much, when we have to think and feel so quickly because time is galloping on. These are the years when life is happening TO us, it’s later that we get the chance to consider it and wrestle it into shape. From zero to twenty-five years, we are receptors. That’s why I believe that massive luck comes into play. It’s luck if you find yourself in a loving family, if your parents stay together, if no-one bullies you or hurts you or makes you feel small, if you live in a safe country, if you have good teachers, if you don’t experience the early death of someone you love, if you make enduring friendships, if you have grandparents, if you have good health, if you have good eyesight, if you enjoy your own company, if you don’t have wide hobbit-like feet, if your hair doesn’t fall out… just luck. There’s pretty much nothing you can do about any of the above and yet they prescribe a large part of how you turn out. It don’t seem fair.

For me, it’s obvious that the biggest part of who we become is… who really made us. We are made of everyone around us when we are little, and we are shaped by who we choose to have around us when we are adults. I look at who made me, and although I stand short and steady like a Weeble here in my own shoes today, I walk in the footsteps of all who went before me. Mainly family, but also friends. I am made of all of them. Even the dodgy ones.

Here’s my list of key players:

GOOD GRANNY MARJORIE

A tiny woman made entirely of cake and powerful, unquestionable goodness. She taught ballroom dancing in her youth and had a phenomenal collection of dolls in her loft. Dolls from all around the world, in national dress, all colours and sizes. Some had eyes that shut. All had pants, because if they arrived without, she’d make some to preserve their dignity. Granny hadn’t travelled, but the dolls had. Us grandchildren cuddled up to her in the warm bed in her cold front bedroom to have stories. There was a Camberwick spread on the bed and condensation dripping down the window. She wore size 3 shoes. Some were gold and had a heel for dancing. I could fit into them perfectly when I was about nine. It was THRILLING. She was the only family member other than my bro and mum that I told about the adoption of my daughter, because she was the most TRUSTWORTHY person I ever knew. I felt safe and loved around her, and she taught me how to be a granddaughter. I will always, always miss her.

EVIL GRANNY LILLIAN

Known to our side of the family as ‘Fag Ash Lil’. She was a handful, a tricky ol’ broad with a colourful history, a sharp tongue and a short fuse. She loved rabbit-skin fur coats, sparkly bling and clacky shoes. She loved gin and arcades and the British Legion and bookies and darts. I often slept in the same room as her when I was a child, on what she called the ‘cot’ (a pull-out bed). She would leave her teeth in a glass on her bedside table overnight and set an alarm to wake her at intervals so that she could drink from a flask in the night. She SAID it was water …

She showed me how to play cards and she taught me not to be ashamed of, or deny, our working-class background. She had a formidable eff-off attitude that I admired, though could never quite emulate. She wasn’t the most naturally maternal of women, but that didn’t have to matter to me because she wasn’t MY mother. For me, she was as bold as brass, ballsy and fearless, a consummate survivor.

MY DAD

He took his own life when I was nineteen, so my memories of him are limited to only those nineteen years. I feel cheated I didn’t know him adult to adult. Mind you, do we ever know our parents as such, I wonder? Perhaps we are always stuck in the amber of the child–parent relationship to some extent. I CERTAINLY am when it comes to him. Such an important significant, influential person in my life … ripped away just as I might have been starting to understand him. I realize that I lionize him to some extent. I don’t care. He gave me that armour of confidence by reminding me often how much I mattered and how beautiful I was in his eyes. When you’re a curious little dumpy girl, your dad’s eyes are the main ones you see yourself reflected in. They are your mirror, and in that mirror I saw and believed I was bloody gorgeous. I knew, because he told me, that I was NOT to accept second best when it came to boys, that I was NOT to be grateful for their attentions, that I was deserving of kindness, humour and respect, that I was a prize worth cherishing, that I absolutely knew how to love another, because look how well I loved my family. He told me to protect my reputation and my dignity. He told me I was truly, resolutely, undeniably loved. And I knew it to be fact. I knew it in my blood and bones, and no-one could ever persuade me otherwise. Not ever.

Here’s a thing I know FOR SURE, and something we need to tell all the dads. Know this, and be in NO doubt about it, your daughters, your darling daughters, will measure every significant male in their lives by you. So, sorry to say it, but you’d better be a tip-top enough example of a proper man. Be someone to aspire to. Be decent and kind and cheerful and understanding and generous and funny and selfless. No pressure then …

My dad was a gentle chap, a bit too sensitive for the macho world he inhabited, I suspect. He was easily embarrassed in the company of those he didn’t know so well, but at home he was certainly not. He was funny and silly. Interesting, considering the fact that from the age of sixteen, and most likely before, he suffered crippling depression, and in a time when it was shameful to have such an illness he, of course, attempted to hide it. From colleagues, friends, family, and, I guess, from himself. I didn’t know my dad was mentally unwell. I knew he had bouts of ‘migraine’ and took to his bed with ‘piles’. We would sometimes tiptoe about the house so as not to wake him if he was in a darkened room, ‘getting some rest’. I didn’t know he was in seven kinds of hell at those times, fighting off the black dogs that were ravaging him.

His suicide imploded our family and drenched us in sadness. That is undeniable and a massive part of my history … BUT, here’s the more important thing … we SURVIVED it. Ironically, I think one of the reasons our little four-sided square of a family became a strong, solid triangle after he was gone was because of him, and all he taught us about how to look after each other. That’s exactly what we did, right from the off, from the dark minute when we discovered what he’d done, that awful minute, so pitifully different to the minute before … when we had a dad. A lovely dad.

So there I was, aged nineteen, having had a childhood full of safety, nurture and plenty of adventures, teetering on the edge of adulthood and loaded with grief. All I knew was that, true to the memory of my dad, I needed to step forward. Just like when he taught me to swim as a nipper living in Cyprus, where he was posted with the RAF. I was six when we moved there, and as so much time was spent by the sea, I really needed to know how to swim. He coaxed me into the water, deeper and deeper. He caught me when I leapt from rocks into the darker blue water. Never once did I think he wouldn’t catch me. He was the one holding me carefully when I discovered that if you kick like this and that and flail this way and that, you do eventually remain buoyant, you breathe, you swim, you survive. Very quickly I wanted a snorkel and flippers. I sorta believed I had gills. I spent hours under the water, closely inspecting the phenomenon of magnified skin pores on the back of my hand, my toes, sand, rocks, fish. All of it was wondrous. The regular sound of my own breathing underwater through the amplification of the plastic breathing tube was comforting and became the soundtrack of my private, splendid submarine life. I had no fear.

Above water is equally exhilarating, because that’s where hours and pruney-skin-hours of delight happen when Dad pretends to be my own personal dolphin, whilst I hang around his neck and he speeds through the water faster than any human surely can. How strong and broad and brown are his shoulders and how lovely is it to feel the water splashing on my face? How safe do I feel when he tosses me in the air and I splash into the water nearby only to be scooped up by my dolphin dad who is, by now, even making the required dolphin noises?!

However cruelly short my time was with my father – after all it only existed in the Spring of my life – it couldn’t have been more potent. I remember so much, and it all sticks. I try to live my life as a tribute to him. I always have him with me, as my energy and my engine. I go steady. Left foot. Right foot. Breathe.

If there can be anything learnt from such a disaster, it is this for me – it’s really OK to fail. Nothing in life should matter so much that it trumps our will to live. Let’s risk failure and be as brave as we can for as long as we can. And let’s choose to live.

MY MUM

Of course, literally made me.

I started like a lot of us, as a baby. A red-spotted lump of a baby, with scarlet fever, apparently. My two-year-old brother thought Mum had given birth to a giant screaming strawberry. It was a lengthy, complicated birth, Mum liked to remind me. She also wanted me to know that in those days of poor dental care, little info about calcium, and no fluoride in the water, she donated her top teeth to my bro, and her bottom teeth to me. When I think about it now, how strange it must have been to have entirely false and ill-fitting teeth from your twenties onwards.

There was a rod of steel running right down my mum’s spine. Although she suffered plenty of self-doubt, she was pretty much fearless and tackled everything head-on. Sometimes she was so caught up in her valour, she lost sight of how audacious she might have become on occasion. She was a ferocious advocate for the underdog. A powerhouse. Extremely loving but quite strict. You would want her on your team. A monster love truck with eight reserve tanks if you should have need of them, plenty for everyone.

A working-class woman, she always felt that she was being looked down on, and so she shook off her natural West Country burr and adopted a faux posh Mrs Bouquet-type accent. I think lots of people did that in the fifties, there was a kind of received pronunciation of the Queen’s English that newsreaders and broadcasters used, and that was the ideal. Occasionally, usually when ruddy angry, Mum would slip up and we would hear her familiar Plymouth accent flood back. Both she and my dad were born and raised there. Janners, we call ’em, and proud.

Since Dad was in the RAF and consequently our family were regularly moved around the country and abroad to different bases, Mum had to find work wherever we ended up. She re-invented herself so many times, adapting and surviving at every turn. She was a serial truth-shifter, re-telling and re-framing situations to suit her purpose and her moral compass.

I loved the smell of her and, though she’s been gone nigh on five years, I can still summon it if I close my eyes and conjure her up. It’s a mixture of stew, lily of the valley, smoke, washing powder, coffee, bosoms and pasties. Unmistakably Mum.

GARY

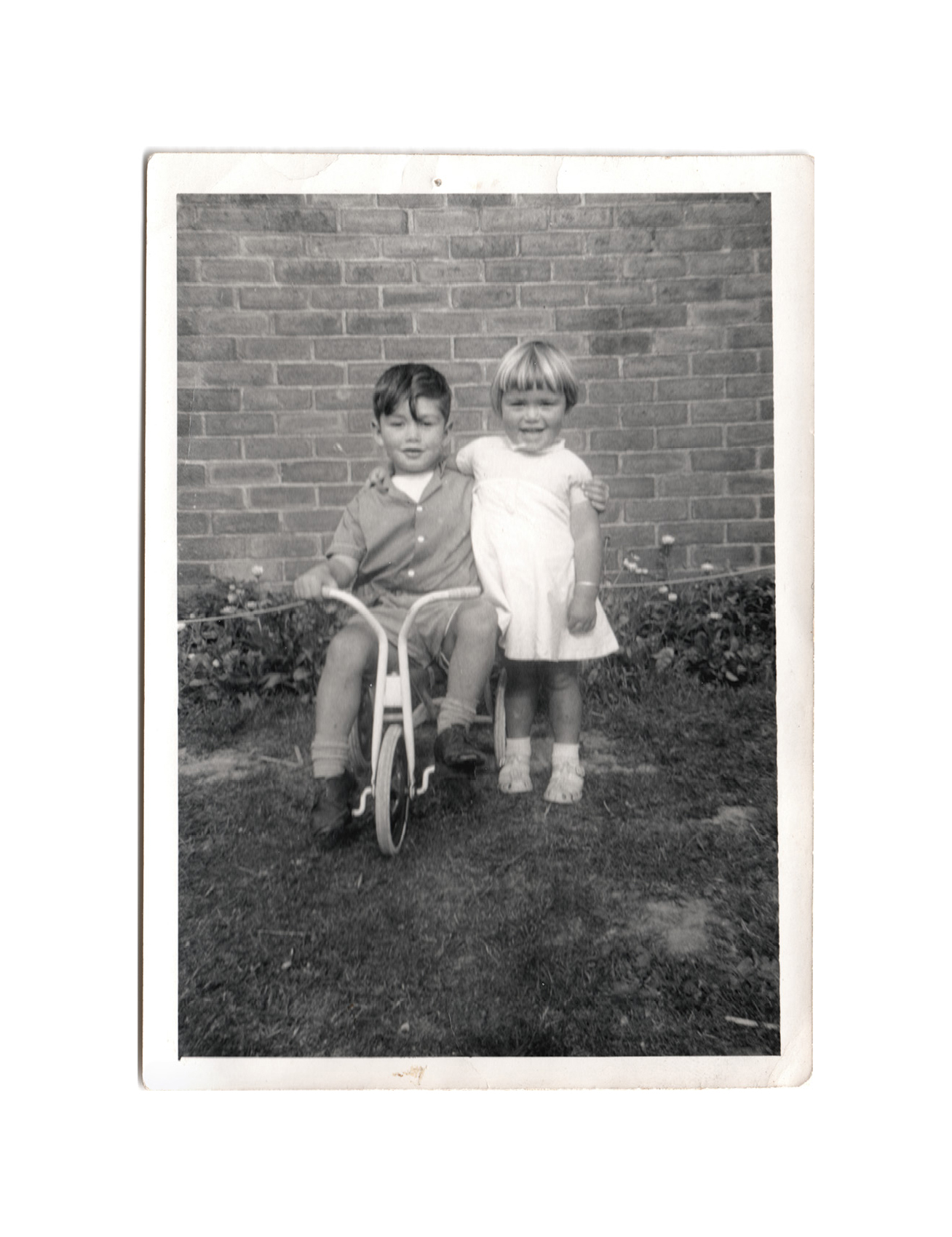

Those are the folk who taught me how to be a granddaughter and a daughter, and it was Gary who taught me how to be a sister. Having an older brother is a blessing and a curse when you’re younger, for both of you. He once beat up some boys who threatened to pull my pants down when I was five, so I always knew he had my back. On the other hand, he did regularly pin me down with his knees on my shoulders and dribble on my face. He did also explain to me on various occasions throughout our childhood that I was the only person he could gleefully actually murder, and I think he may have had good reason. I knew full well how to annoy him and, inexplicably, I couldn’t stop myself doing those very things AD NAUSEAM until I wound him up tighter than a coiley-coiled coil, then I would stand back, watch him explode and then loudly complain to Mum and Dad that he had shouted at me. Evil little sis, born to torture him. The fact is, throughout our entire lives we have looked out for each other, as taught by Dad, and to this day, he is the first person I call when big stuff happens. He has known me my WHOLE LIFE, every living minute of it. Not only has he known me, he knows me, and I really know him. He is my blood and I love the bones of him and his family. Plus – he’s a great dad, so for me, that means he’s a great man.

Safe in the surety of the love of these five, my passage through childhood into spotty young adulthood was pretty smooth. I didn’t realize that the relative plain-sailing was in actuality a chance for me to load up my knapsack of confidence in readiness for the tornado that would buffet us all when Dad died. On reflection, I now know that all the life provisions that were carefully, thoughtfully packed away in those early years are what have provided me with sustenance ever since.

Every positive experience, however small and everyday it may seem, is another unit of provisions for the knapsack, which gets fuller and heavier. You never mind carrying it if it’s chock-full o’ good stuff. In fact the weight helps to remind you of it, of what family feels like, of what shared responsibility and mutual concern are. Oh, Mum and Dad are laughing – I’ll have that. Now they’re kissing – have that. Now they are arguing – not sure if I want that. Oh I see, now they’re making up and forgiving each other – yep, I’ll have that. They’re teasing me – I’ll have that. We’re all going to see the latest James Bond film together – definitely have that. We’re singing Beatles songs in the car – yep. And on, and on … Unfortunately, the opposite is also true of course. That knapsack can be very heavy indeed if it’s full of hurt and shame and anger. So heavy, in fact, that it can prevent you from moving forward, it can drag you to the ground and collapse you.

The learning is happening in such huge dollops in these early years, it’s easy to be overwhelmed and consequently make tons of mistakes. Of course. There’s no problem with that so long as you can recognize that’s what they are. That’s ALL they are. You are young, it’s all reversible, all salvageable. No guilt necessary. Little do we know that actually, in this strangely elastic stage of our youth, we are forming our own template over which we will trace many moments of our lives thereafter, honing and adjusting all the time, altering the settings.

Does time pass differently in these formative years? I’m only thinking of the lazy, long, long summers right next to the yearly birthdays that seem to occur every other week, too fast, too fast.

For some, those years of birth to twenty-five contain babyhood, school, college (or not), relationships, work, marriage and babyhood again (or not). A whole huge cycle happens. It’s in these years that our passions are fierce, our bodies are ripe, we believe we are invincible and we KNOW we are RIGHT. Why on earth wouldn’t we make tons of mahoosive decisions? Yes, I will get engaged at nineteen. Yes, I will have a tight curly perm. Yes, I will have careless sex with an entirely unsuitable boy without a condom and worry myself sick for six weeks. Yes, I will spend more money than I earn on a piece of Monty Don jewellery and get into big, fat debt.

And anyway, this is when we are asked to make choices. We are constantly measured and when we are sixteen, we are expected to decide our workplace future by beginning the cull of subjects that we may not excel at. We start to focus on who we think we are and who we might turn out to be. If we are very lucky, these choices will be nearly right. If we are even luckier, those older and wiser around us will remind us that they too are still trying to work it out and that any possibly misguided choices made at this lovely young age can be rectified anytime later.

- OK to try.

- OK to make mistakes.

- OK to not know.

- OK to try again.

- OK to make better mistakes.

- OK to know a tiny bit more.

It’s Spring. The sap is rising. The buds are opening. It’s a time for HOPE and OPTIMISM. Pull your knapsack on tight and bring it on …