His wife, Evelyn Nesbit, was, by age sixteen, New York City’s most famous model. Photographs of her dressed in skimpy virginal attire, with auburn hair cascading down her bare shoulders, began to appear on penny postcards and in national periodicals. Her innocence and beauty captivated millions of men and one in particular, Stanford White, who had a penchant for virtuous adolescent girls and a wallet large enough to attain them. He first spotted her performing a bit part in a Broadway musical. Since Evelyn was a minor, White befriended her mother. He convinced Mrs. Nesbit that he only had her daughter’s best interests in mind and began to shower her with gifts. Evelyn soon became smitten by her much older, married benefactor, whom she affectionately called “Stanny.”

Meanwhile, Harry K. Thaw, a younger and more wealthy suitor, began vying for Evelyn’s attention. Thaw wanted desperately to marry her. When White learned of their budding relationship, he warned Evelyn that Thaw had experienced several psychotic episodes in the past that his family fortune had made disappear. But Thaw kept that side of himself hidden from Evelyn. Shortly before her eighteenth birthday in 1903, he squired her, along with her mother acting as a chaperone, on a grand tour of Europe. Thaw’s plan was to get Evelyn away from White to determine the extent of their romantic involvement.

Stanford White and Harry Thaw both vied for the attention of Evelyn Nesbit, considered to be one of the most beautiful women in America in the early 1900s. Penny postcards bearing her image were purchased by the thousands.

Halfway through the monthlong sojourn he persuaded Mrs. Nesbit to return home. When she did, he rented a secluded castle for himself and Evelyn in the German countryside. Once they were alone, Thaw convinced Evelyn to open up about her relationship with White. She reluctantly admitted that White had taken her virginity during a night of heavy drinking. Thaw became so unhinged by her disclosure that he violently raped her. In the months that followed their return to America, Thaw begged Evelyn to forgive him and that he was a changed man. She finally believed him. The two were married in April 1905 and settled down in his family mansion in Pittsburgh. Although they were far away from New York City, Thaw could not get past the fact that White had defiled his bride. He began to formulate a plan to make White pay for what he had done.

Thaw took to carrying a pistol, ostensibly for his own protection, but he had other ideas for it. He made arrangements to take Evelyn on a voyage to Europe in the summer of 1906. The night before boarding the ocean liner, Thaw agreed to take Evelyn to see a new show at Madison Square Garden. A combination of happenstance and bad timing put White and Thaw on a collision course that evening. Thaw noticed White’s arrival and immediately excused himself. The chorus had just finished singing the song “I Could Love a Thousand Girls” when Thaw walked up behind White and fired his revolver three times. White keeled over on the table. Silverware and wineglasses crashed to the floor. During the pandemonium, Thaw casually made his way to the elevator, where he was arrested by Patrolman Debes.

Stanford White, New York City’s most prominent architect, had a penchant for young women… and also the money to get them.

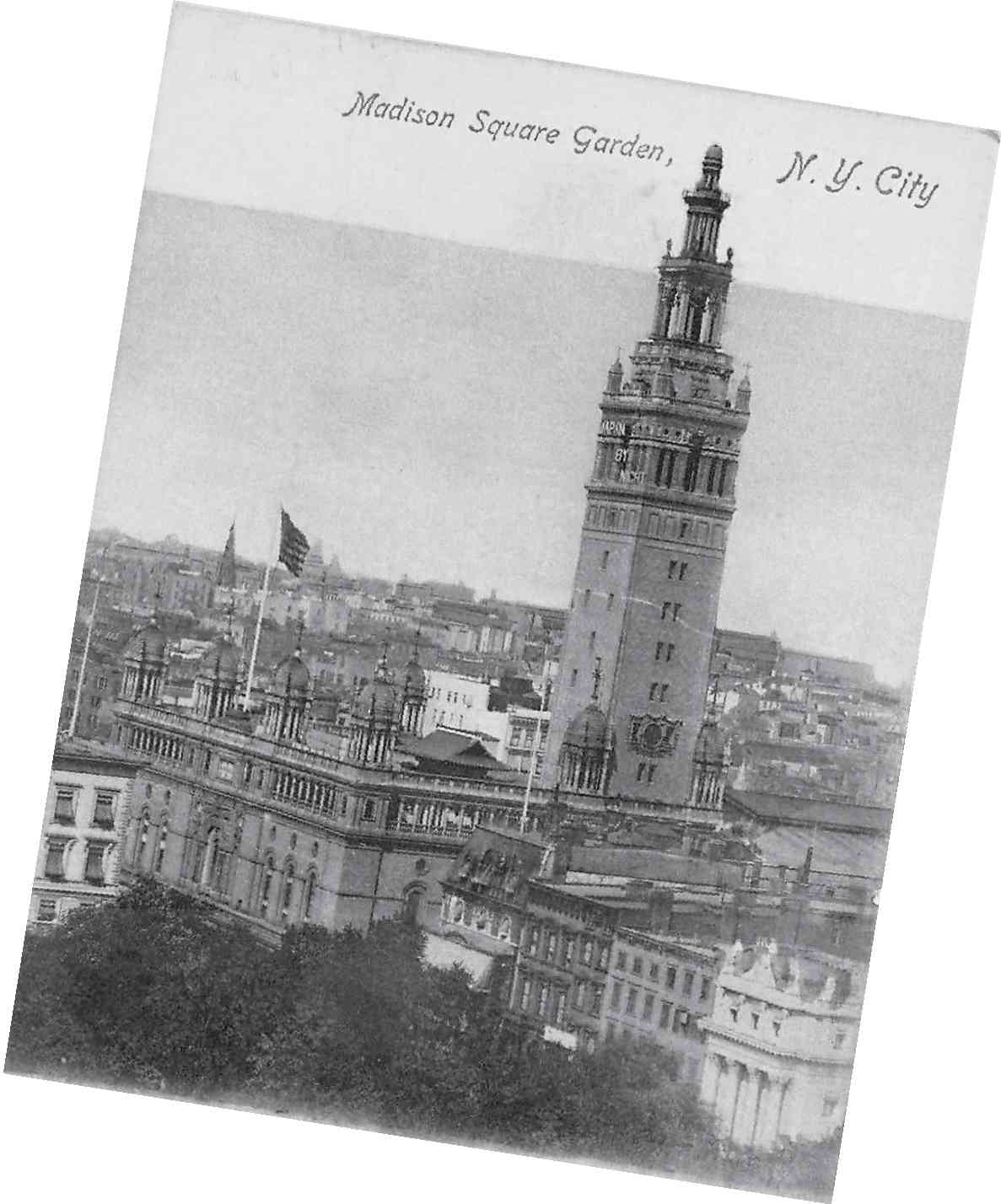

The Stanford White–designed Madison Square Garden in 1906.

Thaw pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity. He was remanded to the Tombs prison, where his wealth insured that he would dine on steak from Delmonico’s washed down with the finest Scotch money could buy.

The newspapers proclaimed Thaw’s 1907 murder trial “the Trial of the Century.” The star witness was his beautiful wife, Evelyn. The entire country was riveted to her testimony; unbeknownst to most of them, Thaw’s mother had made financial arrangements with Evelyn to insure she portrayed her schizophrenic son in the best possible light. The first trial resulted in a hung jury, the second in a verdict of not guilty by reason of insanity. Thaw spent the next several years in a sanitarium, where he enjoyed regular conjugal visits with Evelyn. Security was so lax that at one point he escaped and made his way to Canada. Eventually he was captured and returned to the United States.

On July 15, 1915, his lawyers finally won Thaw’s freedom. One of the first things he did upon his release was divorce his wife. Thaw would go on to have many run-ins with the law. As for Evelyn, her ex-husband’s penny pinching ways made her life miserable. Before she passed away in 1967 at age eighty-one, Evelyn told a reporter, “Stanny was lucky he died. I lived.”

Harry Thaw’s fortune allowed him perks that other inmates could only dream of. Here he is seen in his prison cell enjoying a steak from Delmonico’s.

Most murder investigations start with the police finding a body. Police began using photography at the beginning of the nineteenth century to document crime scenes.

Fourth Deputy Police Commissioner Arthur Woods was a Harvard graduate who studied special methods of policing abroad before accepting a position with the NYPD in 1906 at the behest of Police Commissioner Theodore Bingham. In 1908 the police commissioner charged him with reorganizing the Detective Bureau. As part of that mission Woods formed the nation’s first police squad to specialize solely in homicide investigations. New York cops dubbed the unit “the Murder Clinic” for its reliance on the scientific method to solve crimes.

Prior to that, detectives worked on whatever case their captain assigned them to. Woods believed that the public would be better served by detectives devoted to investigating a specific type of crime. He went on to create other specialty units to deal with pickpockets, missing persons, narcotics, radicals, and safecrackers.

Captain Arthur Carey, a seasoned detective, was placed in command of the new unit. But right from the start his handpicked team was hindered by the fact that under the law, nobody—including police officers—could disturb a dead body until the coroner examined it first. Valuable clues necessary to determine the time of death were lost after blood dried and rigor mortis set in.

In addition, detectives assigned to branch offices in the outer boroughs did not like being told how to do their jobs by specialists from Headquarters and were reluctant to share information with their colleagues.

Nevertheless, Carey set out to teach his subordinates all he knew about the art of murder. To better understand what type of injuries were fatal, he had his men study the effects of bullets (by firing rounds into the shaved heads and bodies of hog and calf carcasses to simulate gunshot wounds), burns, lacerations, punctures, poisonous substances, including chemicals and acids, explosives, and telltale ligature marks.

Although Carey’s detectives became experts in their field, they fell back on the Third Degree whenever their scientific methods failed to identify a suspect. This caused the naysayers in the Department to whisper that they were no better at their craft than any other detective on the force.

With a change in administration in 1910, and twenty-two unsolved homicides on the books, the Homicide Squad was disbanded, and Captain Carey was transferred from plainclothes back to uniform. But four years later Woods returned to the Department, this time as police commissioner, and undid all of the changes made by his predecessor. Carey returned to command the re-formed Homicide Squad and remained in command until he retired in 1928 as an inspector. He went on to write a book about his experiences, Memoirs of a Murder Man.