In early September 1920, a former mental patient and self-proclaimed psychic named Edwin Fisher warned friends to stay away from the Wall Street area because a bomb was going to blow it up. Whether he had inside information or true psychic powers was never determined, but his eerier prediction did come true. At noon on Thursday, September 16, 1920, a bomb exploded in the heart of New York’s Financial District, causing more than $2,000,000 ($25,000,000 today) in property damage. Thirty-nine people were killed and another two hundred maimed. It remained the single most deadly terrorist attack in the United States until April 1995, when a bomb in Oklahoma City claimed 168 innocent victims.

Within an hour, 1,700 patrolmen supplemented by a regiment of army regulars from Governors Island were on the scene to restore order. It took several hours for the police department, working in conjunction with the federal government’s Bureau of Investigation (forerunner to the Federal Bureau of Investigation) to actually decide whether or not the explosion was an accident or a bomb.

The corner of Wall Street and Broad Street, the location where the Wall Street bombing took place. JP Morgan Bank is on the right.

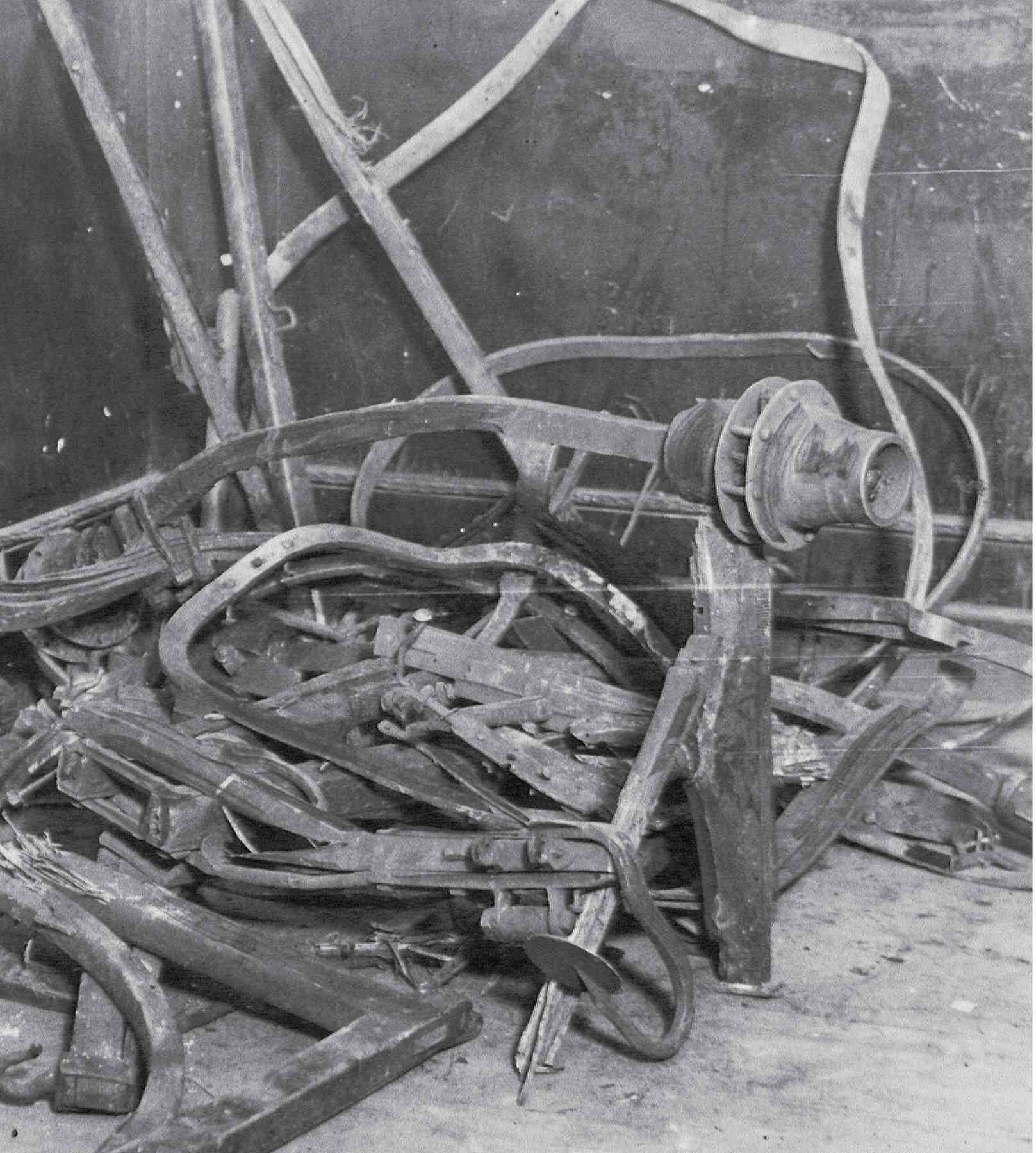

The twisted wreckage of the horse-drawn wagon after the bomb went off. Police tried to trace the wagon’s owner by questioning the blacksmith whose horseshoes were found still attached to the severed hooves of the horse.

According to several eyewitnesses, shortly before noon, an old, rickety, horse-drawn wagon, commonly used to ferry butter and eggs, pulled up to the curb in front of the Morgan Bank located at 23 Wall Street directly across from Federal Hall. The back bed contained a large wooden crate. Messengers and deliverymen were a constant presence in the area, so no one gave it a second thought when the driver and his helper climbed down and disappeared into the crowd.

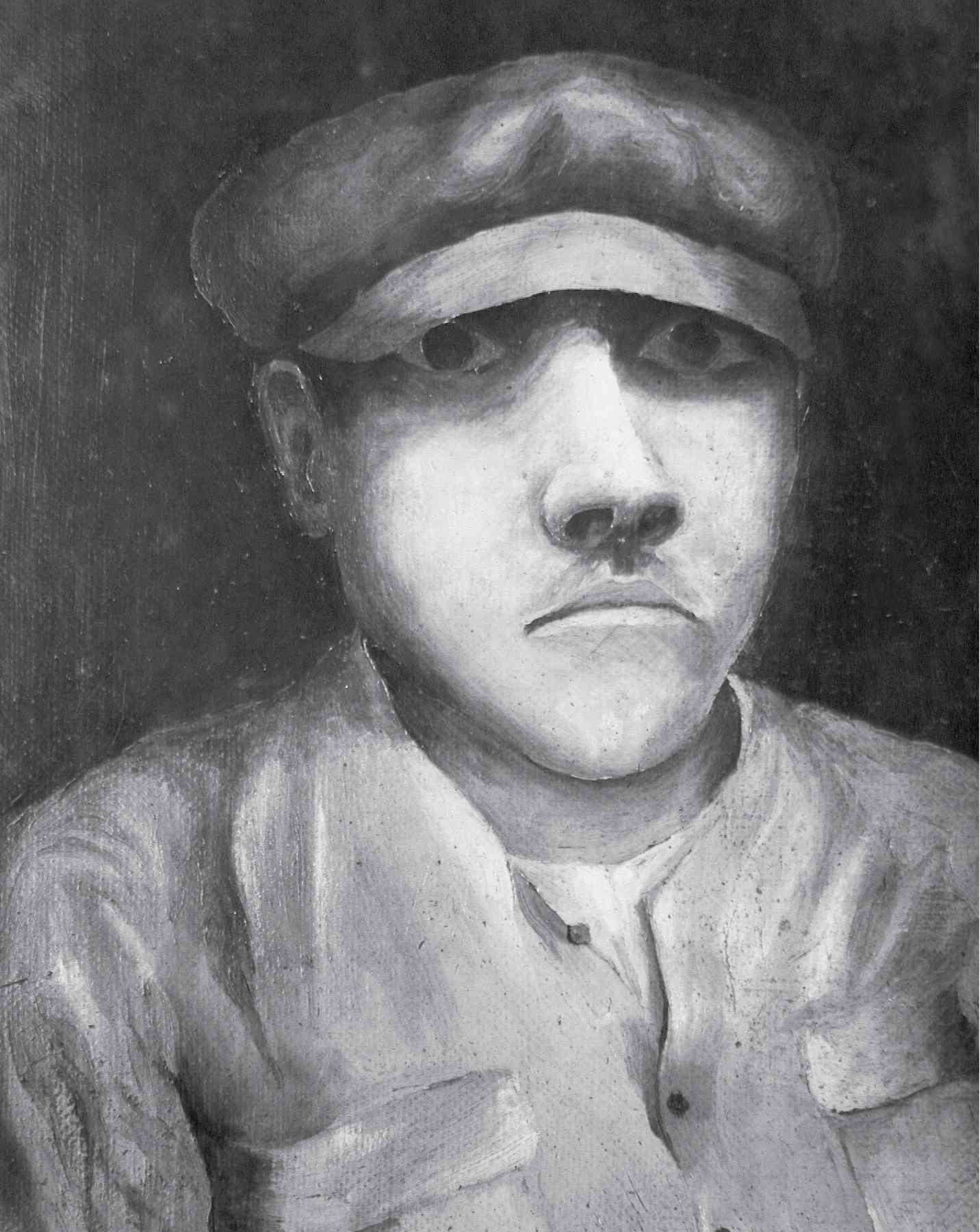

The police sketch of the operator of the horse-drawn wagon that carried the bomb to Wall Street. He was never identified.

Minutes later, as workers from the Stock Exchange and nearby brokerage houses sat across the street on the steps of Federal Hall eating their lunch, a powerful blast erupted from the very same wagon, in effect making it one of the first car bombs in history. The concussion shattered windows and rained shards of plate glass down on the crowd. The impact of the iron shrapnel against the bank and hall’s facades left deep pockmarks still visible today.

Some evidence was inadvertently destroyed when the bankers arranged to have the streets swept of debris so that they could reopen for business as usual the next morning.

The Bomb Squad was still able to reconstruct the device and determined that it contained one hundred pounds of dynamite and five hundred pounds of iron, but had no luck tracking down the origin of the materials. Detectives tried to locate a possible accomplice by tracing the shoes that were still attached to the severed hooves of the horse, but they were unable to prove the blacksmith had any connection to the bombers. Although he provided a description of the men who hired him to shoe the horse, he was too afraid of reprisal from the bombers to answer any more questions.

Police examined circulars printed up by radicals advocating violence discovered in a mailbox in Lower Manhattan shortly after the explosion, but they failed to identify which group was responsible. Eventually, law enforcement authorities concluded that the Morgan Bank was the target of Italian anarchists affiliated with Luigi Galleani, who had been deported to Italy in 1919 for advocating an overthrow of the United States government, and while arrests were made, not one person was convicted.

The concussion shattered windows and rained shards of plate glass down on the crowd.

Authorities later thought that the anarchist responsible for the Wall Street bomb was Mario Buda. Two days before the bombing, two of his associates, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, were arrested for the murder of two payroll guards in Braintree, Massachusetts. He may have ordered the bombing of Wall Street in retaliation, but it was never proven. Buda, however, went into hiding shortly after the explosion and was not heard from again until 1928 when he resurfaced in Italy, a full year after Sacco and Vanzetti were executed for the murders of the payroll guards.

Noah Lerner, a suspect in the Wall Street bombing, appears in court on May 23, 1923. He was not convicted.