Many assume that the FBI and the NYPD have always had a close working relationship. However in the early days of the Bureau, J. Edgar Hoover realized that to make his agency a force to be reckoned with, the Bureau needed to make spectacular, headline-grabbing arrests of America’s most wanted criminals. In order to do that, it might mean unnecessarily endangering innocent civilians and upsetting other law enforcement authorities.

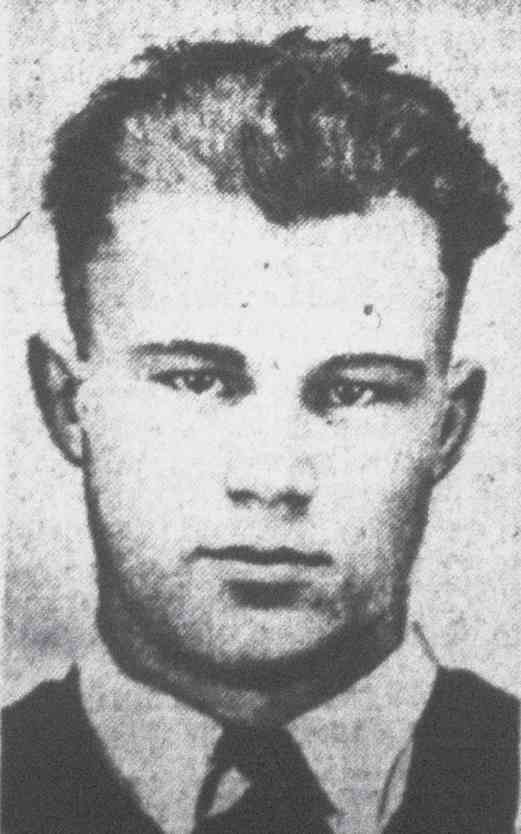

Twenty-five-year-old Harry Brunette was a small-time hood looking to make a big name for himself. A string of bank robberies in New Jersey coupled with the kidnapping of New Jersey state trooper William Turnbull, who had pulled him over for a traffic violation, fulfilled his wish. By November 1936 he was one of the most wanted men in America. The trooper survived the ordeal when Brunette dumped him out of the car on a rural Pennsylvania back road, without his uniform and pistol, before speeding away. A law enacted after the Lindbergh baby kidnapping made Burnette’s crime a federal offense and brought the FBI in on the case. Fortunately, Turnbull remembered the car’s Michigan license plate number and the pretty face of Brunette’s female companion.

Several weeks later the New Jersey state police got a lead that the car in question had been in for repairs at a shop in Manhattan on West 108th Street. The troopers contacted the NYPD in early December for assistance. Employees at the garage identified Harry Brunette as the owner of the car from a police mugshot. A canvass of the neighborhood revealed that Harry had recently married Arline LeBeau and the pair resided on the ground floor of a five-story apartment building on West 102nd Street. Trooper Turnbull eyeballed LeBeau from a safe distance and positively identified her as the woman who was riding with Brunette the night he was abducted. From that point the police had LeBeau and the apartment under constant surveillance. Brunette himself was more elusive and was seldom seen. A plant inside the apartment building told them that he was a night owl who slept most of the day. Since the police considered Brunette armed and extremely dangerous, they decided to wait until they were sure he was asleep before conducting a raid.

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover at the scene of the Harry Brunette raid. Hoover called Brunette (right) “the toughest criminal I’ve seen.”

The New Jersey State Police and the FBI agreed that the NYPD would handle the capture, since Brunette was hiding out in their jurisdiction. As a courtesy, Police Commissioner Lewis Valentine notified Director Hoover of the exact time and date so he could be present during the apprehension, which was set for two o’clock Monday afternoon, December 14.

Valentine never expected Hoover to double-cross him. Hoover arrived the night before with two dozen agents and personally took over the operation. His second in command, Clyde Tolson, would effect the arrest.

At 1:30 A.M., Hoover gave his men orders to blast apart the lock on Brunette’s apartment door with a shotgun. But Brunette, who police knew was always awake at night, was ready for them. He opened fire with a .45-caliber automatic and a pair of .45-caliber revolvers. Even though he was outnumbered twenty-five to one, Brunette refused to surrender.

Hoover ordered tear gas to flush him out. But when the canisters erupted, the curtains caught fire, putting the lives of every resident in the building in danger. Despite the thickening smoke, Brunette fought on, only ceasing fire for a moment so his wounded bride could be helped out of the burning apartment by the agents.

A fire company responded to the scene unaware that a pitched gun battle was under way. The firemen suddenly found themselves dodging bullets in conjunction with dousing flames. They bravely raised their aerial ladder, ready to pour water down on the building if the fire spread. The only member of the NYPD to take part in the shootout was Sixth Deputy Commissioner Byrnes MacDonald, who inexplicably decided to climb a fire ladder leaning against the building in order to shoot down at Brunette through the front-floor window. (Several weeks later Valentine permanently removed MacDonald from night duty after learning how he bragged about his foolhardy actions.)

It took thirty-five minutes for Brunette to run out of ammunition. When he emerged from the smoky haze with his hands up in the air, not a single G-man’s bullet had found its mark. “What a brave bunch of guys,” he sneered as he surrendered. He was led out of the smoldering vestibule toward a crowd of photographers by Clyde Tolson.

The firemen raced inside and put out the fire. Fortunately, the damage was limited to Brunette’s apartment. Miraculously, with the exception of his wife—who had taken a round to the back—no other tenant was injured.

Despite the chaos Hoover was thrilled with the results. He called Brunette “the toughest criminal I’ve ever seen,” but both the fire commissioner and Police Commissioner Valentine were furious with him for endangering so many innocent lives.

Valentine claimed that Hoover did not even know where Brunette was hiding out until he told him. In addition, he accused Hoover of concocting a story of NYPD detectives sleeping on the job to justify his own actions. Hoover later conceded that Valentine’s men had only left the scene momentarily to get a cup of coffee. There also appeared to be validity in Valentine’s statement about Hoover’s lack of knowledge of Brunette’s whereabouts, because Hoover refused to disclose how he got his information.

Brunette pleaded guilty and was sentenced to life in prison just four days after his capture. His wife recovered from her wounds and was sentenced to serve time in a women’s reformatory for her part in her husband’s crimes. Although Valentine and Hoover were forced to cooperate again many times after that, especially during World War II when the FBI was in charge of hunting down spies, their relationship never fully recovered from what happened that night on the Upper West Side.

Police Commissioner Lewis Valentine wrote that the NYPD plan of arrest was “ignored by the federal men who, evidently without concern for the public welfare or for the many families residing in the large apartment house, with tear gas bombs and gunfire staged a raid over the protest of the New Jersey state police and contrary to the agreement entered into by the three departments.”