Scores of blacks from the American South, as well as Hispanics who hailed mainly from Puerto Rico, had migrated to New York during World War II to work on the docks and the factories that supported the war effort. This influx lead to ethnic rivalries, which resulted in a proliferation of violent street gangs that became a public scourge in the 1950s. White gangs in Brooklyn such as the Halsey Bops often rumbled with the black DeKalb Chaplains or the Hispanic Mau Maus or Apaches.

Former New York State Supreme Court Justice and author Edwin Torres was born in the 1930s to Puerto Rican parents in Spanish Harlem. During his childhood, Torres recalled, “Puerto Ricans were not supposed to go east of Park Avenue. Our area was between Ninety-Ninth to 116th Streets,” he said. “The blacks were west of Fifth. There was a tough Italian gang called the Red Wings, who had the entire area east of Park.” When Torres ventured over to the Jefferson Pool in that area, he was set upon by the Red Wings, who beat him with bicycle chains and stickball bats. For safety, it was best to stay with your own.

Salvador Agron learned this early on. Born into a troubled family in Puerto Rico in 1943, he spent the next sixteen years shuttling back and forth between his native island and New York. He joined the Mau Maus in 1958, but after meeting Tony Hernandez, the charismatic president of a Spanish Harlem gang called the Vampires, he quickly switched allegiances.

On the night of August 30, 1959, the Vampires were en route to a rumble against a predominantly Irish-American gang called the Norsemen. The flamboyant Agron was wearing a red-lined silk black cape, while Hernandez was armed with a sharpened umbrella that he planned to use for a weapon. Upon entering DeWitt Clinton Park, they mistook a group of innocent white teenagers for Norsemen. During the ensuing brawl, two youngsters, Anthony Krzesinski and Robert Young Jr., neither of whom had any gang affiliations, were stabbed to death. Another innocent bystander, Ewald Reimer, was tripped, stomped, and stabbed, but was saved from being killed when a benevolent Vampire intervened and said, “He has had enough.”

When asked by police why he stabbed the youngsters, an unrepentant Agron snapped, “Because I felt like it.”

The nation was transfixed by the sheer savagery of the crime. Although thirteen gang members were arrested, the primary killers, Agron and Hernandez, became tabloid fodder after being dubbed “the Cape Man” and “the Umbrella Man” by the press. When asked by police why he stabbed the youngsters, an unrepentant Agron snapped, “Because I felt like it.” While he was in jail awaiting trial, his mother sent him a Bible, which Argon promptly returned.

“I don’t care if I burn—my mother can watch me,” he boasted when discussing the possibility of receiving the death penalty.

Salvador “the Cape Man” Agron and Antonio “the Umbrella Man” Hernandez before being taken to the Brooklyn House of Detention on Atlantic Avenue.

The trial was as spectacular as the crimes. Edwin Torres, by this time the first Puerto Rican assistant district attorney ever hired by Manhattan District Attorney Frank Hogan, served as the second seat on the prosecutorial team. One day in court, Torres said, “The hacks [guards] were taking the ‘Cape Man’ out of the courtroom. As he passed by, he snarled at me and called me a Spanish name that means stool pigeon or traitor. He was a punk and a half, so I jumped up. I still had the ghetto in me back then.”

After a widely publicized trial, Agron and Hernandez were both convicted and sentenced to death in the electric chair. At the time, Agron was the youngest prisoner ever put on death row in New York State. Both had their sentences commuted when New York abolished the death penalty in 1962 for all but cop killers. Hernandez subsequently had his conviction overturned when it was proven that he never actually stabbed anyone. He was released from prison in 1969, and afterward he resided in relative anonymity in the Bronx.

In a 1997 interview with the New York Daily News, Hernandez admitted that he and his gang “destroyed so much that night.” Asked to be more specific, he explained, “Ourselves. The other kids. Maybe the city. We were such fools. I died that night, too.”

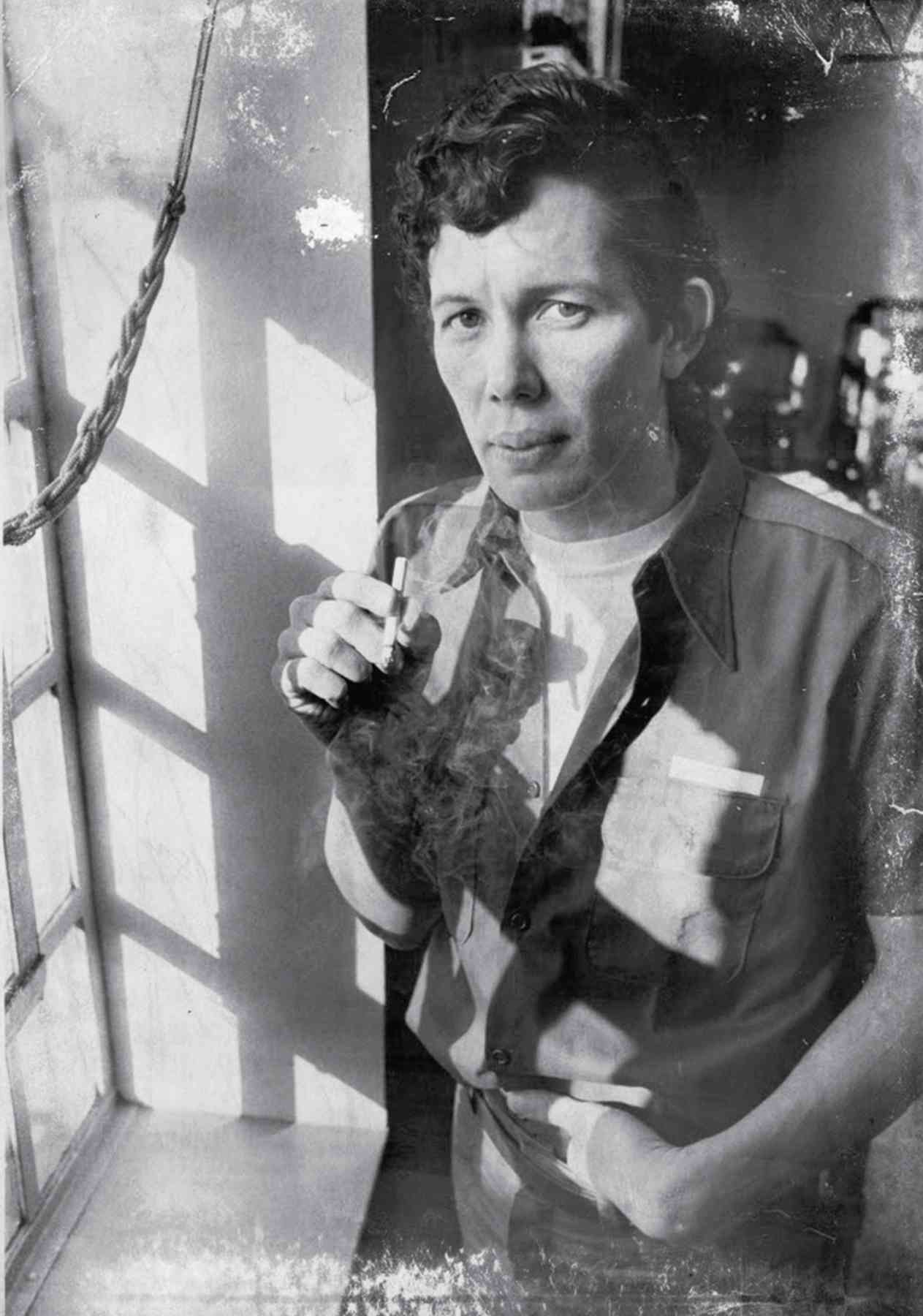

Salvador Agron in Green Haven prison in 1977, two years prior to his being granted parole.

Nearly illiterate when imprisoned, Agron earned a college degree from the State University of New York at New Paltz. He became a model prisoner and was allowed to attend college during the day and return to jail at night. Although he absconded from the program in 1977 and was captured in Phoenix, Arizona, two weeks later, he was found not guilty of escape due to mental illness, and was paroled in 1979. Shortly before his release, he described his transformation to a reporter as a “re-humanization.” Agron found work as a youth counselor, but he died of pneumonia and internal bleeding in April 1986 at the age of forty-two.