On an unusually hot Friday, May 18, 1962, a radio call was broadcast to patrol cars at 3:48 P.M. The dispatcher said it was a 10-30—or, in NYPD parlance, a robbery in progress—at 1167 Forty-Eighth Street in Borough Park, a working-class Jewish and Italian neighborhood in Brooklyn. A follow-up transmission at 3:50 P.M. further revealed that two males had been shot at the scene. Moments later the radio crackled again; this time the dispatcher advised that it was “two MOFs,” or “members of the force,” who had been shot.

Albert Seedman, the detective district commander in Brooklyn, and his driver were the second unit on the scene at the Boro Park Tobacco Company, a small brick and mortar warehouse that sold tobacco and confectionary items. Although he was Jewish, Seedman could not help but cry out, “Holy Jesus!” when he walked in the door. Lying dead, facedown on the floor, was Luke Fallon, one of Seedman’s best veteran detectives. His partner, Detective “Big” John Finnegan, was lying faceup with eyes open, but just as dead.

The tobacco wholesaler was owned by two brothers, Robert and David Goldberg. Because the Goldbergs dealt with so much cash, their business was deemed a “robbery prone location,” by the NYPD. As such it was closely monitored by the local precinct cops and plainclothesmen. Moments before their deaths, Fallon and Finnegan had stopped in to make a purchase. Fallon bought cough drops, Finnegan a box of chocolates for his young wife.

The two detectives had been on decoy patrol in the neighborhood that day in a taxicab. It was later determined that as Fallon and Finnegan exited the location they observed two suspicious men, one taller and much heavier than the other, loitering around the corner from the warehouse on New Utrecht Avenue. Both were wearing dark sunglasses and brimmed hats to conceal their faces. The detectives drove away as if they had not noticed them. After a few minutes they returned in the cab. The men were not there. Something told them to check the warehouse. They immediately became suspicious after looking in through the front window. It was eerily quiet. They drew their service revolvers and took a position just outside the entrance. If the place was being robbed, they thought it was more prudent to catch the bandits as they fled rather than barge in and put the lives of the workers and customers in danger.

Their instincts were right. During the short time it took for Fallon and Finnegan to circle the block, the two suspects had covered their faces with handkerchiefs, drawn their guns, and entered the location to announce a stickup. They separated David Goldberg from Robert and the staff, and locked them up in the rear storage room. Then the pair marched David Goldberg to the office and demanded he open the safe.

The thinner of the two thieves returned to the storage room, planning to fleece the employees of their personal property. Unbeknownst to him, there was a slide lock on the inside of the storage room door. When the employees refused to open it, the perpetrator attempted to force his way in and in the process inadvertently fired his gun. “Just an accident,” he assured them. “Just open the fucking door and nobody will get hurt.”

But once the detectives heard the shot, all bets were off. They rushed in with Fallon leading the charge. The heavier gunman was caught by surprise. He yelled, “Don’t shoot. I give up,” and dropped his weapon. When Fallon saw the gun hit the floor, he ran past him, assuming that Finnegan would retrieve the weapon. It proved to be a fatal mistake. The perpetrator grabbed his gun first. Fallon turned around and fired one shot at him before he was blasted in the chest. Finnegan rushed forward and took two slugs. He managed to fire off six rounds, but none of them hit his target. He collapsed and died trying to reload his revolver as the perpetrators fled the scene.

He collapsed and died trying to reload his revolver as the perpetrators fled the scene.

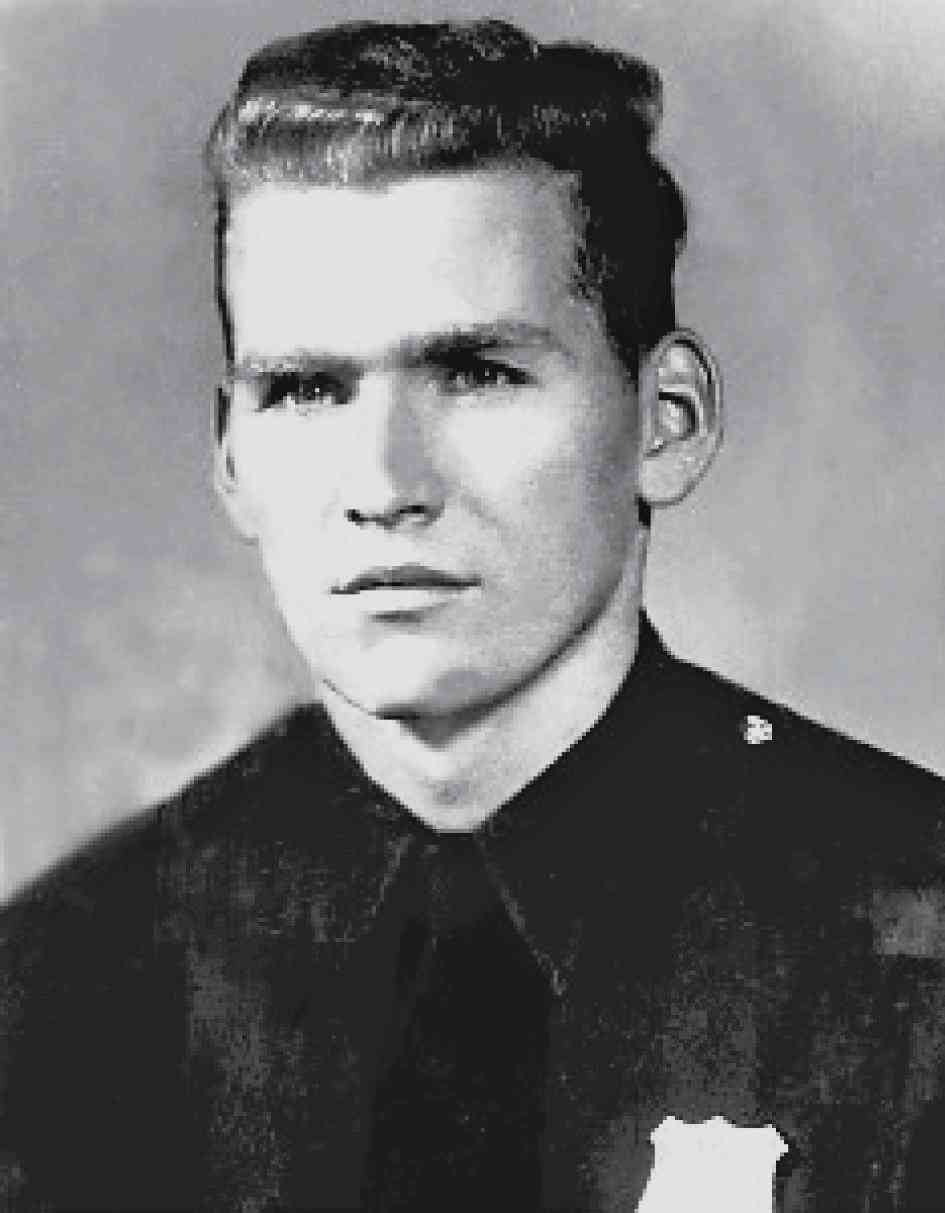

The 1962 double murder of Detectives Luke Fallon (left) and John Finnegan was the first time two partners were killed together in a line-of-duty shooting since 1927.

It was the first time in New York City since 1927 that two officers were killed together in the line of duty. The police response to the shooting was fast and furious. The suspect who fired the fatal shots was identified as Anthony “Baldy” Portelli, a portly twenty-five-year-old parolee. He skipped to Chicago, but was arrested within days after being ratted out by a friend.

With cops scouring every corner of the city, the thinner suspect, a twenty-four-year-old ex-convict named Jerome Rosenberg, arranged for Gary Kagan, a neighbor of his parents and a photographer for the New York Daily News, to surrender him to the police at the Daily News building on East Forty-Second Street. Rosenberg was taken into custody on May 23, 1962, the day of his twenty-fifth birthday.

Two weeks after the murders, Governor Nelson Rockefeller signed a law that limited the death penalty to killers of police officers and prison guards. Portelli and Rosenberg were convicted of the homicides in February 1963 and sentenced to die in the electric chair, only to have Rockefeller commute their sentences to life imprisonment.

Portelli died in prison in 1975, but Rosenberg, despite being an eighth-grade dropout, was a very intelligent man. He took correspondence courses from the Blackstone School of Law in Chicago. He became a renowned jailhouse lawyer who, among other things, was a “legal representative” for inmates during the Attica prison uprising in 1971.

Rosenberg was so enamored of his prison moniker, “Jerry the Jew,” he had it embroidered on his prison shirts. However, he became a victim of his own fame. A 1982 biography by Stephen Bello called Doing Life: The Extraordinary Saga of America’s Greatest Jailhouse Lawyer was made into a television movie four years later starring Tony Danza as Rosenberg. The notoriety from the public quite possibly was the reason he was denied parole every time he became eligible. Not counting the time he spent in prison prior to the Fallon and Finnegan murders, Rosenberg served forty-six straight years on the other side of the wall. At the time of his death in June 2009 at the age of seventy-two, he was the longest-serving inmate in the New York State correctional system. In a postmortem article for the Huffington Post, radical New York lawyer Ron Kuby called Rosenberg “the greatest jailhouse lawyer who ever lived.”

One person who had an altogether different assessment of him was the daughter of Detective Fallon, Joan Scheibner. As far as she was concerned, “he was the scum of the earth.”

Prisoner Jerome Rosenberg is flanked by Detectives Leo Rostow (L) and Edwin Nally (R) as he is booked at Borough Park police station.