September 11, 2001, was a turning point in the history of New York City. Eight Muslim hijackers, in a premeditated act of pure jihad, crashed two jets into the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center and killed 2,996 innocent people. Among the dead were twenty-three members of the New York City Police Department who took part in the ill-fated rescue effort. Contrary to what many people think, they were not the first NYPD officers killed by jihadists in New York City. That unfortunate distinction belongs to a twenty-nine-year-old Emergency Service Unit police officer named Stephen Gilroy.

Shortly after nightfall on Friday evening, January 19, 1973, four armed Sunni Muslims led by convert Shuaib Raheem, aka Earl Robinson, entered John and Al’s Sporting Goods store on the corner of Broadway and Melrose Street in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Their plan was to steal enough weapons and ammunition to begin a deadly crusade in the “Borough of Churches.”

But an employee managed to trip the silent alarm without their knowledge. Since the store sold guns and ammunition, patrolmen from several different Brooklyn precincts converged on the scene within moments and blocked their escape. Rather than give up, the gunmen took eleven employees and customers hostage and began shooting. The barrage shattered the storefront window and the windows of other businesses in the vicinity. Police officers pinned down behind their patrol cars immediately returned fire, but had to be more discreet in their aim because of the hostages.

As the gun battle was going on, traffic screeched to a halt on Broadway. Panicked pedestrians ran in all directions in search of shelter. Police cordoned off the blocks around the store with rope and wooden barricades. Residents were ordered to stay inside their apartments, and service on the elevated BMT line that passed directly above the store was suspended, stranding thousands of straphangers.

The Emergency Service Unit was called in along with an armored personnel carrier/rescue ambulance to provide a tactical advantage in the event a decision was made to enter the store. Police officer Gilroy was positioned behind a steel pillar under the elevated train tracks. Other officers climbed onto the roof of the store and adjacent buildings. The area was shrouded in darkness, because streetlights had either been shot out or had their electricity cut off, and visibility was limited by pouring rain. Raheem still managed to target Gilroy. When Gilroy shifted his body slightly to get a better view of the store, Raheem squeezed the trigger on a high-powered rifle. A single round struck Gilroy in the head. He died almost instantly. A second patrolman took a bullet to the leg trying desperately to get Gilroy into an ambulance.

Rather than give up, the gunmen took eleven employees and customers hostage and began shooting.

The store manager, Jerry Riccio, recalled that after Gilroy went down, Raheem waved his gun and bragged, “We can kill anyone else we want.”

Unbeknownst to the police, one of the jihadists, Yusef Abdullah Almussudig, had suffered a serious abdominal wound during the initial exchange of gunfire and required immediate medical treatment if he was to survive. From that point on, the gunmen fired only sporadically, but remained defiant. The police, however, would not shoot another round.

The year before, at the 1972 Olympics in Munich, heavily armed German police stormed the Olympic Village in a futile attempt to save Israeli athletes being held at gunpoint by Palestinian terrorists. The rescue attempt failed miserably, resulting in seventeen deaths. New York City Police Commissioner Patrick Murphy considered the possibility that if a trained hostage negotiator had been present to deal with the terrorists, the outcome might have been different. With that in mind, he ordered a select group of NYPD officers to begin immediate training as hostage negotiators. This was the first time the new tactics would be employed, a literal trial by fire. It was also a drastic departure from the department’s past practice.

The siege continued for forty-four more hours. Police hostage negotiators aided by community and religious leaders engaged the gunmen with little success, but as long as the hostages were alive, Deputy Police Commissioner for Community Affairs (and future police commissioner) Benjamin Ward, a black man and former lieutenant, believed that time was on the department’s side. Initially authorities communicated with a bullhorn, later with a walkie-talkie, and finally a telephone. A female hostage was the first to be released. She was also the first to inform detectives that a gunman had been shot and that they intended to fight it out until the end. A Muslim minister, who subsequently spoke face-to-face with the jihadists, confirmed her information.

The gunmen released a third hostage the following afternoon. In return the police sent in food, cigarettes, and a black physician, Dr. Thomas Matthew, to treat Almussudig. He and a nurse stayed inside the store for three hours, but neither could convince the Muslims to surrender. Raheem did, however, give the doctor a handwritten statement expressing his views. It read in part that Muslims would continue to fight until all religions in the world were for Allah.

The big break came when the gunmen left the remaining hostages unattended for a few minutes. Store manager Jerry Riccio was able to lead them to an old staircase concealed by a thin piece of sheetrock. He punched through it and led all of them to the roof, where police officers were able to escort them to safety. Without their leverage, the jihadists were left with only two options: shoot it out and die, or come out peacefully and surrender. On Sunday at 4:45 P.M., they chose the latter, thereby ending the forty-seven-hour ordeal.

Although Mayor John Lindsay praised the police commissioner for resolving the hostage crisis without further bloodshed, many of his fellow officers believed Gilroy died for nothing. Patrolman George Bell said, ““Why should we have let their guys call the shots? We should have flushed them out in any way possible. If it had been me, I would have used bazookas, hand grenades, anything.”

Officer Stephen Gilroy

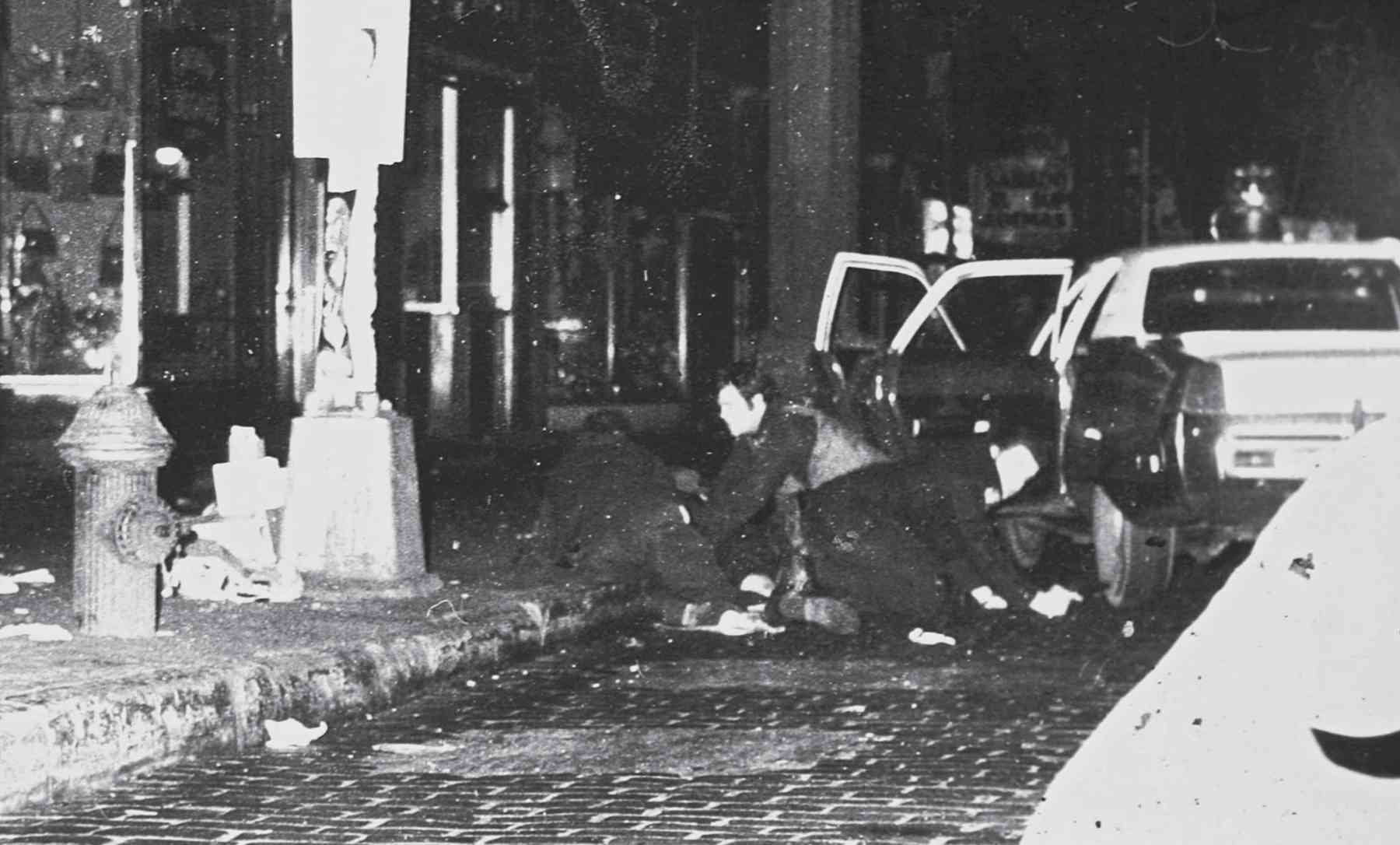

Officers trying to help injured Stephen Gilroy.

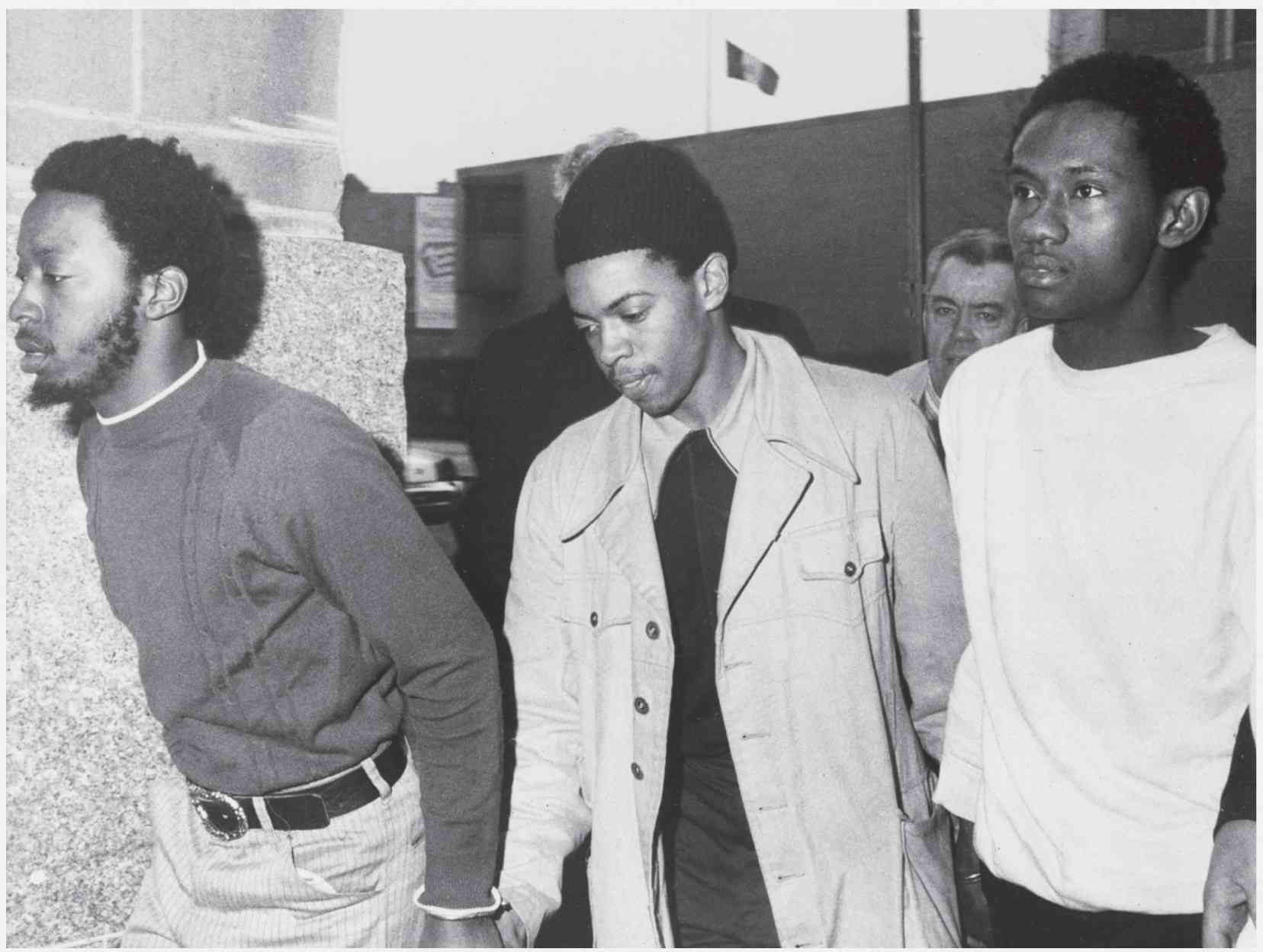

Dawud ar-Raahman (white shirt) and Shuaib Raheem (trench coat) booked in a Brooklyn station house.

The four jihadists were sentenced to long prison terms. Despite continuing to espouse their views while in jail, Yusef Abdullah Almussudig was released on parole in 1998. He died in 2003, two years after the World Trade Center attacks. The group’s leader, Shuaib Raheem, was released in 2010 at age sixty. Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association president Patrick Lynch called it the worst decision possible by the Parole Board.

Ironically, the tactics that were developed and used successfully over the years as a result of this first confrontation with Muslim jihadists were modified by Police Commissioner William Bratton in 2015. In situations involving active shooters, particularly jihadists who are only interested in causing death and destruction, the NYPD will actively engage them from the start rather than attempt to establish a dialogue first and lose valuable time.

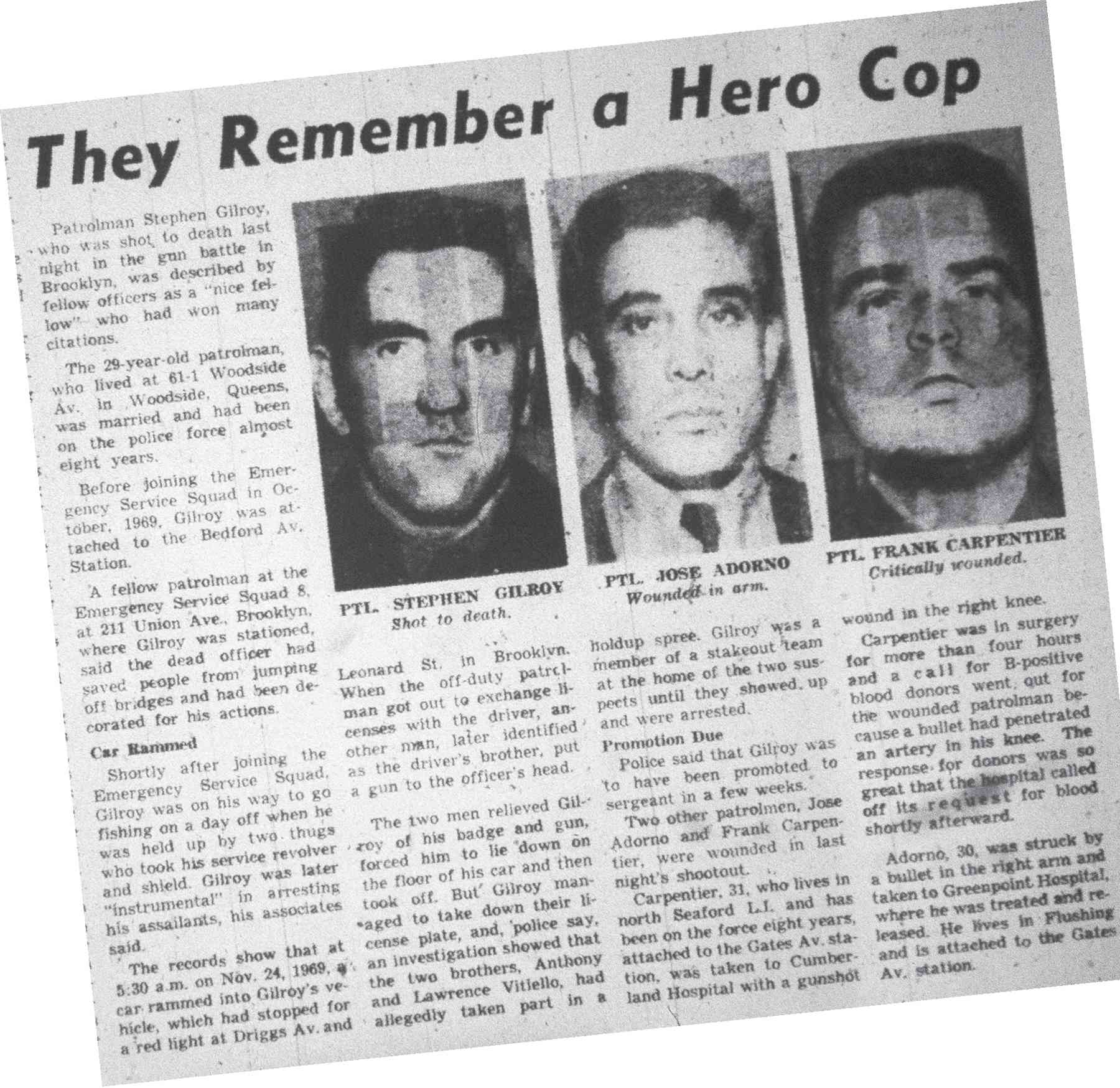

A New York Post article that details the death of Gilroy and the wounding of patrolmen Jose Adorno and Frank Carpentier.