THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA, blared the New York Post’s front page. A secondary header read, POLICE LOOKING FOR SEX SLAYER AT MET. The New York Times seemed equally overwrought. Its lengthy front-page story was headlined VIOLINIST, MISSING AT INTERMISSION, FOUND SLAIN AT MET. Uncharacteristically, the Times account was accompanied by a detailed schematic of the opera house’s many levels and, most astonishing, a photograph peering down into the abyss of the airshaft, giving readers a lurid opportunity to visualize the victim’s death plunge.

The NYPD assigned sixteen detectives exclusively to the case. Another fifty were called in to help interview an estimated one thousand opera house workers. Even so, the investigation dragged on for weeks. Finally, on the morning of August 30, 1980, Twentieth Precinct detective Michael Struk, who caught the case, and Detective Gennaro Giorgio, of the Manhattan Homicide Task Force, announced that they had obtained a confession from a twenty-two-year-old high school dropout named Craig Steven Crimmins, who was employed by the Met as a stagehand. He had a particular fondness for alcohol, which was revealed later at his trial when a defense witness testified that Crimmins had downed approximately twenty beers during the twelve-hour period leading up to Mintiks’s disappearance.

Crimmins admitted, “I killed the lady. She was talking to me, trying to be nice. I decided to gag her.”

Assistant District Attorney Roger S. Hayes theorized that Crimmins and Mintiks had a chance encounter on the elevator that fateful night. He was inebriated and made a lewd pass at her. Mintiks responded by slapping him in his face. Crimmins became angry. He overpowered Mintiks and dragged her out of the elevator into the sub-basement, where he attempted to rape her, but not before demanding she remove her tampon. Mintiks tried desperately to fend him off. She broke free momentarily, but he caught her in the stairwell and forced her up to the roof on the sixth floor. There he tore off her clothes, bound her hands and feet, gagged her, and ultimately flung her down the ventilation shaft to her death.

Crimmins insisted that he was going to leave her on the roof to make his escape until she began squirming. “As I was walking away, I heard her pouncing up and down, and that’s when it happened. I went back and kicked her off [the roof and down the air shaft].”

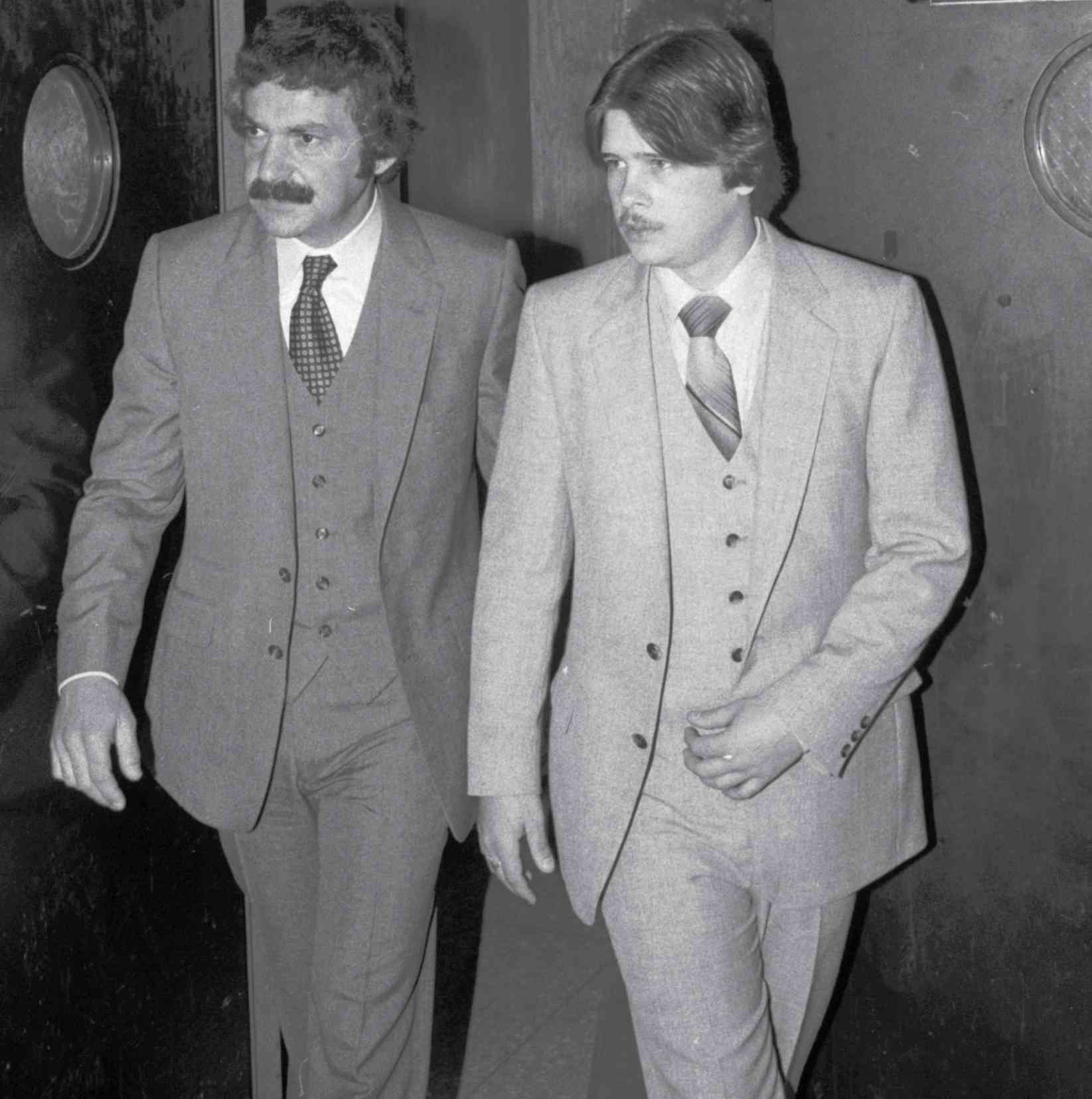

Crimmins was facing one count of intentional murder and another count of felony murder, the latter being murder in the commission of another crime—in this case, attempted rape. His lawyer, Lawrence Hochheiser, contended that Crimmins had an IQ of only eighty-three and had been spoon-fed his confession by the police over the course of three days and denied an opportunity to speak to counsel. He painted his client as little more than a patsy who was no match for the incessant badgering he faced from a pair of savvy detectives and a wily prosecutor, all of whom had mercilessly grilled him until he finally broke.

On June 4, 1981, after eleven hours of deliberation, the jury forewoman announced not guilty on the intentional murder count, but the panel of seven women and five men returned a guilty verdict for felony murder. Crimmins’s college student girlfriend, Mary Ann Fennell, collapsed in court and had to be taken to the hospital. Edward Crimmins Sr. later told the New York Post that his son spent his first night behind bars crying like a baby.

On September 2, 1981, Manhattan Supreme Court Justice Richard Denzer sentenced Crimmins to twenty years to life, while pointing out that the slaying had not been a random act but was meant to cover up the attempted rape. To this day, Crimmins remains a prisoner of the Shawangunk Correctional Facility in Wallkill, New York. He has since obtained a high school diploma and an associate degree in substance abuse counseling. Nonetheless, in May 2014, he was denied parole for an eighth time. In his opinion, he was remanded not so much for the crime that he committed but for the notoriety the crime generated.

Craig Crimmins (right) with his lawyer Lawrence Hochheiser.