THE SAD TRUTH about Paris is that it does not have a historical centre. Or to be more accurate, it is a hole in the ground. Just as all roads lead to Rome, so all métro lines will take you eventually to métro stop No. 7, Châtelet -Les Halles, "le ventre de Paris" the centre of the world as Parisians would have it, and a great big hole in the ground as every metrostopper will notice. It was where the old north-south axis of the long-haul trade met the east-west flow of the Seine, where the foodstuffs for the city were collected for distribution, where the architects and planners drew a natural cross in the soil from which the streets and the underground would derive their shape.

" Châtelet " simply meant the point of exchange; une halle is a covered market—a word that, applied to the vast central markets that served Paris, had to be put in the plural. Baron Haussmann designed his whole project for the rebuilding of Paris during the Second Empire from a cross he drew over the Place du Châtelet, confirming once more the centrality of this point in the city, and the centrality of the market. Residents of the area still thought they were at the centre of everything in the 1960s: "Les Halles is the geographical centre of Paris and of the French Republic," said one inhabitant in an official report made in 1968—a perfectly outrageous remark. Yet for people living in the proximity of Victor Baltard's iron and glass pavilions, which housed Les Halles, this kind of comment seemed as natural as the observation that the planets circled the sun. After all, Les Halles were the central marketplace of Paris. And, second, back in 1848 this was the central battleground in the fight to establish the French Republic.

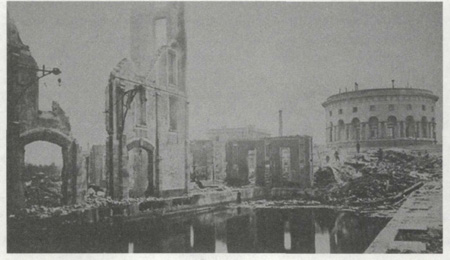

The district of "Les Halles" was vast, extending well beyond the complex of Baltard's glass pavilions. Many of the old buildings and streets that fed off the markets are still there, and they constitute one of the most enchanting parts of Paris. When the new mayor of Paris, Bertrand Delanoë, wanted to show the Queen of England a typical quarter of Paris, he brought her here; Monsieur Duthu and his smiling colleagues at the Patissier Stohrer have never stopped speaking of the day, in April 2004, when Queen Elizabeth II walked into their shop to buy a cake. You can spend two days wandering around Rue Montorgueil without exhausting all the treasures it has to offer. But why is it there? All those patissiers, the delicatessens, the caterers, the brasseries and the little restaurants are by-products of a huge marketplace that is no longer there. In London, the old pavilions of Covent Garden were preserved. In Paris, where they covered half the district, they were destroyed. The market itself was moved out to Rungis, next to Orly airport, in 1969. In 1971 the demolitions began. Through most of that decade all that was left of the "belly of Paris" was a vast hole in the ground, le Trou.

Paris, since the time of the Roman walls, has always been subjected to ambitious urban plans, and change, of course, is the sign of a living city. But in the past, planners — such as those of the cathedrals or those of nineteenth-century theatres, town halls and boulevards—were supported by an army of anonymous artisans who chiselled stone, creating those alluring little details one generally attachés to a work of art; today plans are set in flat concrete. A journey from the underground of Châtelet -Les Halles to the surface brings to the eye that blunt fact.

In the 1980s the "belly of Paris" was turned inside out and upside down. The surface was transformed into a garden, while beneath one's feet there developed the largest underground railway station in the world, transporting over 800,000 souls a day. The station forms the pivot of the largest underground shopping centre in the world, the Forum des Halles, catering every year to 41 million consumers of clothes, handbags, postcards, pens, pocket calculators and laptop computers. There are twenty-three cinemas down there, set in huge concrete cells. Line 1 (following the modern east-west axis) crosses Line 4 (the old north-south axis) here. Line A of the RER, the rapid transit system which stretches into Paris extra muros, crosses Lines B and C: heaven help the poor English tourist who arrives at this point from Roissy airport with his heavy bags and a covey of tired children; he has a mile's walking to do down unending tunnels interspersed with three or four flights of concrete staircases. The labyrinth is so vast that the architects who designed it had to name the station after not one, but two places. Indeed, two whole quartiers, Les Halles and the north bank of the Seine, were ruined for good by the construction of this den, Paris's new underground crucifix, a calvary of sore feet.

In twenty years the concrete of the métro station has turned a dirty grey; in eight centuries the decorated stones of Saint-Eustache have never ceased to cause marvel. The contrast between ancient and modern is edifying—and not new— ÉmileZola made a similar observation on this spot 150 years ago. It was indeed the leitmotiv of his novel Le Ventre de Paris which gave this district its nickname.

ZOLA, IN THE summer of 1872, was at an early stage of his research on the novel when he neatly noted down, in a bound exercise book, the view he got of the southern facade of the Église Saint-Eustache: "Rue des Prouvaires, choked: wine merchants, coal merchants, etc.; one can see, beyond the Halles, a porch of Saint-Eustache, two rows of windows at the level of the arch, surmounted by a rose window. Flying arches on both sides." That is exactly the same southern perspective of the church that one has today from the métro station—only we look through bare concrete walls. Zola ran his eyes through a cluttered covered alley framed by cast-iron pillars and glass. It must have been a pretty sight.

Zola's novel would open with a night convoy of wagons carrying vegetables from Nanterre to the central Halles; on their way they pick up Florent, a refugee from the penal colony of Cayenne, who has fallen, starving and exhausted, by the wayside just beyond the Pont de Neuilly. Half conscious, Florent is carried into the "belly of Paris," to the Pointe Saint-Eustache—just a few hundred yards from where he was arrested after the shooting on the Rue Montmartre, which had followed Napoleon Ill's coup d'etat of 2 December 1851. But the place, he discovers, has been entirely transformed. The historical centre of Paris has disappeared. The old buildings have been knocked down. The streets have gone. Replacing them are "gigantic pavilions whose roofs, superimposed on each other, seemed to him to grow, to stretch out, to lose themselves in a hazy dust of glimmering light." Through slim Fish-bone pillars of iron he looks up, in the dawn's greyness, to perceive "the luminous face of Saint-Eustache," last vestige of the Middle Ages. So the mid-nineteenth century was another age like ours, a time of destruction and transformation.

On 2 June 1872 Zola had had lunch with the famous critic and novelist Edmond de Goncourt. De Goncourt noted in his diary that Zola, who was then thirty-two, looked "weak and nervy." Zola described over lunch the punishing method he had developed for writing "a novel on the Halles, an attempt to paint the plump people of this world." Every day he worked from 9 to 12.30 and from 3 to 8 p.m. First he drew up an ebauche, or draft, then he would make detailed notes on location-spending entire nights, as well as days, walking around the Halles—and only after a full review of the characters and their habitat would he start to write his novel. "The general idea is: the belly— Le Ventre de Paris, Les Halles . . . —the belly of humanity and by extension the governing bourgeoisie, chewing and ruminating, sleeping it off, in peace with its pleasures and its commonplace honesty." At the time Zola spoke to de Goncourt, he was only four years into his vast Rougon-Macquart cycle, an epic on social and political life under the Second Empire which he would complete twenty-five years later.

Thus it was a young Zola who wrote Le Ventre, and this shows. Zola gets his historical facts wrong, some of the characters are a little artificial and it takes him too long to get the plot moving. Zola does not reach the grandeur of the later novels, such as Germinal on the northern coal mines, or La Terre set in the Beauce. But that is not the point. What we find in Le Ventre is a detailed portrayal of life in the Halles, the belly and the heart of Paris —the sights, the crowds, the sounds and the smells in and around Baltard's famous pavilions shortly after they were set up. Le Ventre de Paris is a priceless historical document.

When Zola takes you into a wine merchant's bar on Rue Rambuteau you are stifled by the smell of pipe smoke and gas lamps — something you could not imagine today without Zola as your guide. When you come out of the métro at the Porte du Jour you may reflect that this was the former Pointe Saint-Eustache where 150 years ago the wagons lined up to deliver their goods to the central market. We know the noise was deafening as the goods were unloaded, that the live fowl were packed in square baskets, the dead fowl in deep beds of feather, while whole calf carcasses were wrapped in tablecloths and laid out like children in baskets.

Baskets and more wicker baskets—there was barely a place to stand. Women carried baskets piled high on their heads. We know the "songs of the markets"—"Madame, madame, venez me voir, à deux sous mon petit tas?' "Mouron pour lesp'tits oiseaux! Mouronpour lesp'tits oiseaux!"— and if we are not aware that mouron is French for "chickweed" it doesn't matter very much. The fruit sales girl at her stand had plums wrapped in paper and laid out on flat baskets. She and her fruit gave off a whiff of orchards, while the old saleswoman next to her had pears that looked like sagging breasts and apricots with the cadaverous yellow flesh of a witch; fortunately the Allee des Fleurs lay just behind her. The new Halles of the mid-nineteenth century seemed like "a huge modern machine, a gigantic metal stomach, a people's furnace of digestion, bolted down and riveted." And we know all that thanks to Zola.

Zola faced vicious criticism in the nineteenth-century press for his graphic details, which his detractors said did not ennoble human beings but portrayed them rather as animals. Zola always retorted that they were animals. "You put man in the brain, I put him in all his organs," he wrote in 1885 to one of his most persistent grousers, the great literary critic Jules Lemaitre. "You isolate man from nature, I do not see him without the soil from which he comes and to which he returns. I feel him stretching out everywhere, into his being and beyond his being, into the animal of which he is the brother, into the plant, into the stone." Zola's characters grew out of their environment; the slightest detail mattered, often told in a lurid manner that shocked. Zola, not surprisingly, never achieved his lifelong ambition to be elected to the Académie Française.

He was not at all romantic about Les Halles. His fascination in the natural environment led him to the study of architecture and, in the case of Les Halles, to the stark contrasts between ancient and modern styles of building. Zola was an unhesitant supporter of the modern. The character of Claude Lantier, a visionary painter, takes the positive view on contemporary art; he looks up at the face of the Église Saint-Eustache through the delicate cast-ironwork of Baltard's pavilions and exclaims, "Iron will kill stone!" And he marvels. Enough of these whingers who claim industry kills poetry; look at the modern beauty of those pavilions! Today, standing at the same spot, one can appreciate how reinforced concrete kills iron.

Zola wanted to create, with Le Ventre, a modern, contemporary version of Hugo's Notre Dame de Paris (The Hunchback of Notre Dame). As the Gothic cathedral was the central feature of Hugo's celebrated novel, so would the iron pavilions be central to Le Ventre. Zola's Mar-jolin, found in a pile of cabbage leaves, would play the role of Hugo's Quasimodo. Marjolin grows up in the pavilions of the Halles as they are being constructed—thus providing Zola, to the delight of his readers, ample opportunity to explore every corner of the site, including its secret cellars, which few could describe today In one of the pivotal scenes of the book the beast in Marjolin gets the better of him; he attempts, in the "black air" of the chicken cellars, to rape the curvaceous Lisa, who keeps a char cuterie—or delicatessen—on the other side of Rue Rambuteau. Zola sets his scene up with dead geese and rabbits hanging from the brick vaults, burning gas lamps that give off no light, and the rumbling sound of the market above; it is the thick alkaline odour of guano and rabbit urine that breaks Marjolin's timidity and causes him to "throw Lisa down with the force of a bull." Through the cellar's windows Lisa can hear the sound of feet passing by upon the covered, cobblestone street outside. The scene, predictably, offended many nineteenth-century readers.

Claude Lantier was inspired by Zola's childhood friend Paul Cezanne. Zola mixed with the Impressionists—Édouard Manet, Gus-tave Courbet and Claude Monet—at the café Guerbois in the rural reaches of Les Batignolles before they were known as Impressionists. Much of the book reads like an Impressionist manifesto. But Claude's remarks are more contemporary still; they put one in mind of a twentieth-century British artist much appreciated in Paris, Francis Bacon. Bacon was obsessed with meat dripping red. So was Lantier. It is, in fact, astonishing just how much of Zola's prose on Les Halles portends Bacon. Zola has Claude exploring the butcher's pavilion right opposite the Église Saint-Eustache, an area now converted into a garden of trellises, arcades and arbour pathways: around the pavilion flowed streams of blood into which Claude dipped his feet. At the tripe stands he saw packets of mutton trotters unwrapped, calf tongues showing the points where they had been torn from the throat, beef hearts hanging like bells; the great baskets of sheep's heads conjured up the thought of an interminable line of sheep waiting their turn at a guillotine. But the real horror was in the cellars where, in the thick atmosphere of a charnel house, the butchers broke open the sheep heads with mallets. Nineteenth-century readers were not accustomed to this kind of description, almost commonplace in our own literature.

Today's glass and steel Pavilion des Arts stands where Baltard's Pavilion de la Marée, the fish market, once stood. Florent, the hero of the novel, finds a job as a government inspector of the pavilion. Every day he walks between the carreaux where the fish are laid out, the glass roof above him creating a dusky light, and he hears the drone of the crie'es—the many auctions—along with the distant sound of bells. Every morning there are the same stinking puffs of air, the same spoilt breath of the ocean which blows around him "with great waves of nausea" (one might think of Sartre's famous novel, or of Siiskind's more recent Perfume). A slight dizziness, a vague weariness. An anxiety rises in him which turns into "vivid over-excitement of the nerves." The 1968 report on popular opinion in the district of the Halles showed that there was not too much praise for this reeking market: "It is invasive, dirty, noisy, and inimical to other activities." Talk to the people who remember it. "The Halles were a bit sinister, you know," one old lady told me.

In the novel, Zola's fugitive from Cayenne discovers that his brother has opened a charcuterie on the north side of Rue Rambuteau, just opposite La Marée. The brother and his wife, Lisa, offer him a chambre de bonne, under the roof, on the fifth floor. Florent finds his job in La Marée and at night, unable to sleep, looks across Rue Rambuteau at Baltard's glass roofs. But Florent was not the only person looking out from his window. In Le Ventre there are always other eyes spying across the streets and the alleys, and they would combine and condemn Florent; the whole quartier of the Halles would in the end forge an alliance of spies, renegades and turncoats that would send him back to le bagne, the penal colony.

Zola incorporated the houses, the streets and the pavilions into his unfolding drama. The novel is so graphic because it was founded on a geographical reality, minutely observed by the author. When a room, a building or a street reappears in the novel for a second or third time, one knows that something significant is about to happen.

One critical frontier—in the novel, in historical reality and so it remains today—is Rue Rambuteau. It was named after a Prefect of Paris, the Comte de Rambuteau, who, in 1841, knocked a forty-foot-wide thoroughfare across the medieval city centre from the Église Saint-Eustache to the edge of the Marais; it thus presaged Baron Hauss-mann's massive transformations a decade later. During the 1850s, in which the novel is set, Baltard's pavilions wiped out the buildings on the south side of the road so that Rue Rambuteau became the dividing line between Vieux Paris, or old Paris, and Les Halles, between ancient and modern. And that is exactly what one sees there today On the south side is the contemporary Forum des Halles, with its shopping bazaar and cinemas; on the north side the older Paris, with its food shops, restaurants and countless little treasures awaiting the visitor.

Zola described Rue Rambuteau as teeming with wagons before dawn during the moment of deliveries; the wagons and horses were then parked in the courtyards of the old houses to the north. The yard Zola described next to the Compas d'Or, on Rue Montorgueil, can still be seen, though the horse manure and clusters of chickens have gone. After the crie'es, which lasted in Zola's day until ten or eleven in the morning, an army of street sweepers moved down Rue Rambuteau to clean up the mess; the smell was appalling. Eyes look out from each side of the street. It was from here, on the corner of Rue Rambuteau and Rue Pirouette, that La Belle Lisa—Florent's sister-in-law—stared across the road, from her high counter in the charcuterie, into the interior of the Pavilion de la Marée. From inside that pavilion her gaze is returned, from the fishmonger's banc, or stand, by that of her great rival, La Belle Normande; it penetrates every floor of the charcuterie. La Belle Normande has romantic intentions on Florent. Other eyes peer, peep and poke across the natural barrier of Rue Rambuteau. High in an old house on Rue Pirouette, through light white curtains, the old spinster and worst gossip of the quartier, Mademoiselle Saget, is keeping watch.

"Does Rue Pirouette still exist?" asked Florent when he arrived, dazed by the presence of the new Halles. It did then, but you won't find it today The underground motor expressway that extends from Rue de Turbigo put paid to that. However, the neighbouring Rue Mondetour is still there: inside the shoe shop on the corner there sits at a high polished zinc counter a striking blonde saleswoman staring out across the street—like Lisa, she can tell you a thing or two about Les Halles. Lisa's charcuterie was described as a "smiling place of live colours singing amidst the whiteness of its marble." It was typical of what you could find on the north side of Rue Rambuteau, and can still find today.

Many of the little alleys Zola described are still there. The spying endured and the rumour-mongering developed, and so the little alleys took on a sinister Parisian tone. Behind Lisa's shop there ran a narrow dark corridor just out of view of the pavilions; once one had stepped into it the only way out was through the back entrance of the shop: a mousetrap.

From the outset Florent, worried and nauseous, has vague premonitions of the trap closing him into the iron belly of Paris. It was one of the abiding features of the district which contributed mightily to the decision, one hundred years later, to pull those pavilions down: inhabitants of the area wanted to "get out"; they felt trapped. The moment Florent places a foot in Les Halles he wants to run away. But he discovers that the wagons have blocked the exit at the Pointe de Saint-Eustache; a potato market creates a barrier on Rue Pierre-Lescot; he follows Rue Rambuteau as far as Boulevard de Sebastopol only to come up against a great pile of carpets and huge handcarts; so he turns back to Rue Saint-Denis where he runs into a "deluge of cabbages." All the way to Rue de Rivoli and to the Hôtel de Ville there are unending queues of wheels and bridled animals lost amid the chaos of merchandise they carry Other carts slowly roll their way back to the suburbs.

That is eventually what Florent succeeds in doing. He retreats with one of the carts to the suburbs. For one glorious day, as the gossiping and plotting within the Halles reaches a fever pitch, Florent, Claude the painter and Madame Francois, a market gardener, drive out to Nan-terre, a rural suburb in those days. Madame Francois fills her cart up with old cabbage leaves from the pavilion rubbish dumps and takes the reins; Florent and Claude Îie down on the leaves and discuss life. They follow the same route out of "rogue Paris"—as Madame Francois describes it—that Florent had taken into the city when a fugitive one year before. At the Arc de Triomphe, where "the winds blow up the avenues in immense gusts," Florent sits up to inhale the first odours of grass which arrive from the fortifications. (Try that today) The Halles, which he had left in the morning, now appear to him as a vast ossuary, a "place of death," dominated by the smells of decomposition. The countryside, on the other hand, breathes life. In Nanterre, that May, he helps distribute the green manure on the soil. In the buzz of the insects and the cracking and sighs of the ground he hears the birth and growth of another generation of cabbages, turnips and carrots, the hum of "death repaired."

Here was the critical message of life and death that would be so essential in the works of Zola, the theme of urban entrapment contrasted to rural freedom. It upset traditionalists, who were shocked by the brutality in Zola's portrayals of daily life, and attracted plenty of criticism from the radicals, who preferred the comfortable, familiar coordinates of class analysis in a writer like Balzac; both camps thought Zola was getting too "biological." Yet all his work was based on minute observation of what he saw about him and, particularly in his depiction of life in Les Halles, contained a heavy dose of reality: the district of Les Halles is a harrowing, if in many ways beautiful, place.

After his day in Nantetre, Florent must return to the belly of Paris and cross that street, Rue Rambuteau, every day. It is at this moment of return that Claude presents his analysis of the human struggle in Paris not as one of social class but as one between the Gras and the Maigres, between the Fat, "enormous to the point of bursting, who sit down to their piggish dishes in the evening," and the Skinny, "bent by hunger, who watch from the streets with the look of an envious beanpole." A recent English edition of Zola's novel is given the title The Fat and the Thin—not entirely without reason. What shocked Zola at the Halles in the 1860s was the juxtaposition of a new consumer society side by side with blue, gaunt poverty, a poverty one does not see today That, along with the feeling of entrapment, is why those pavilions went.

Claude never gets drawn into Florent's politics of the "revenge of the Skinny." He warns Florent against it, for Florent is surrounded by the Fat: La Belle Lisa, who will plot to expel Florent from her house because he threatens her tranquillity and earned wealth; La Belle Normande, who will eventually listen to her mother's advice that Florent was "un grand maigre," probably a murderer, so that she will instead marry Monsieur Lebigre, the wine merchant on Rue Pirouette; and in fact most of Florent's revolutionary friends are from among the "Fat," whose financial interests win out in the end. The Fat are found on both sides of Rue Rambuteau. They populate the stands, the auction markets and the stinking cellars. They are the profiteers of the food chain, the retailers, both large and small. They dominate the ancillary trades on the north side of Rue Rambuteau; they sell the sausages and the an-douillettes; they collect together the leftovers—broken sugar almonds, shattered sweet chestnuts, sweets not fit to be sold in jars—and flog them off in paper cones for a sou. In the mid-nineteenth century there was a popular item called godiveaux, meat balls made up of minced calf innards, beef kidneys and egg: the little Cadine, a prefiguration of Zola's Nana, thinks they look delicious, she puts one in her mouth and pulls a terrible face. There are cheeses in Zola's novel—the aniseed-flavoured gé'romé that "let off such a stench that flies dropped dead around its box," or the limbourg that had a "brusque groan. . . like a death rattle"—which you would be lucky to find in a Parisian shop today, even on Rue Montorgueil.

Today Zola could be taken to task by the "politically correct" for his mockery of the Fat. But this would be to miss the point entirely What Zola is describing is the rapid development of a consumer society in the midst of arch-poverty He describes what it looked like and felt like in the marketing heart of Paris. The manufacture and the tasting of the boudin, the black-pudding sausage, is perhaps Zola's most telling image of the way the Fat tormented the Skinny, the new rich tyrannizing the old poor. Lisa's charcuterie, we are told, produced most of its merchandise itself, apart from a few terrines, rillettes and cheeses that they acquired from "the most famous houses" in Paris. For the fabrication of boudin, everyone would gather in the large kitchen and tell stories to the noise of the cooking pots and mincers.

Using this as a setting, Zola builds up a scene of tragi-comic contrasts that typified his writing. Auguste, an assistant who will betray Florent, brings in two pitchers of pigs' blood which he has beaten into a cream. "Ah, the boudin is going to be good!" he exclaims—"Le boudin sera bon!" Round little Pauline takes the fat yellow cat Mouton on to her crossed puffy legs, looks up at a gaunt Florent and asks him to tell "the story of the man who was eaten by beasts." The skinny Florent tells the story of his own escape from Devil's Island, a story that Zola had in fact drawn from the escape, recounted in a popular autobiographical account, of Charles Delescluze, a leading figure of the Paris Commune, who was shot during the "Bloody Week" of May 1871. As the drama of Florent's story amplifies, so do the smells of the boudin: "Once upon a time . . ."—the brother adds the onions; Florent describes the prisoners" disgusting food—'Auguste, pass the lard," interrupts the brother; and so on. There are critical reactions to the story: Lisa cannot hide her disgust, convinced that "honest" men would never allow themselves to stoop to such humiliation; little Pauline sinks into "wondrous sleep." When Florent ends the story with his hero starving but still alive, his brother proudly announces: "Ilest bon, aujourd'hui, le boudin."

At the publication of Le Ventre de Paris in 1873 there was outrage over the graphic "bestiality" of Zola's descriptions. Paul Bourget, in the respected Revue des Deux Mondes, claimed that the author was somebody for whom the "interior world did not exist"; all his scenes "end up with sensual comparisons that revolt one"; there was "never a word that derived from the soul, which attested to the presence of thought." The conservative Le Pays reported that Citizen Zola lived in "immorality" and "sadism." More than just vicious comment was involved in the reaction; recent research has revealed that the government opened a police dossier on Zola.

The malevolence of the commentary would follow Zola for the rest of his life and beyond. In the 1930s the Hungarian critic Georg Lukacs condemned him for favouring physiological differences in his characters over Marxist distinctions in social class—and Marxists have rarely had a kind word for Zola since. Zola's detailed descriptions of his settings and the physiognomy of his characters were certainly designed to shock and move his readers. Many of the descriptions in his work were indeed bestial, though it is unjust to omit what is stirring and ennobling about them, too.

He was a precursor. Zola's evocation of the animal nature of man preceded the popularization of Darwin in France by a decade; some passages on the abuse of animals in Le Ventre can put one in mind of George Orwell's Animal Farm. The dynamism of Zola's novel is derived from dramatic, often violent, contrasts. The massacre of hundreds of pigeons in the cellar of the Pavilion des Volailles is preceded by a description of doves that Florent notices in the Tuileries Garden. Shortly after the brutal scene in the Pavilion des Volailles, Florent is arrested in Lisa's charcuterie; but not before he has released a finch he had picked up, wounded, on the floor of the Halles. He lets the bird fly through his fifth-floor window into the sky, opened up by the demolitions: the bird flits across Rue Rambuteau to land, for a moment, on the Pavilion de la Marée before it takes wing again, disappearing over the grey glass roofs in the direction of the Square des Innocents. As he is taken away by police, Florent hears his brother, unaware of his arrest, announce in the kitchen: "Ah! Sapristi, le boudin sera bon..."

For anyone looking at this novel as a historical source, the most striking thing about Zola's confrontation of the Gras with the Maigres is that it is founded on a kind of poverty unknown to us today in the West. Nowadays it is the poor who tend to be fat, while the rich are so slim. To be sure, it is still an assembly of "marginals" that collects by the Fontaine des Innocents, former site of the medieval charnel house and now Paris's equivalent of Piccadilly Circus. Many of the drug addicts there today are immigrants: in Zola's day they had travelled from the provinces. Hang around for a while and you are bound to see the police arrest someone, just as Zola would have witnessed 150 years ago. The neighbouring pavilion of butter, egg and cheeses has disappeared, as has the crooked Restaurant de Barratte, which so fascinated Zola. So, more importantly, has the gnawing poverty which Zola described in such detail. On two sides of the Square des Innocents there was a long, semicircular row of benches placed end to end. To escape their stifling hovels on the narrow neighbouring streets, the poor gathered here. Shivery old women with crumpled bonnets repaired rags that they pulled out of little baskets; the bareheaded younger women, their skirts poorly tied up, chattered with their neighbours— Zola had thin Mademoiselle Saget here receiving and spreading gossip. There were suspicious men wearing worn-out black hats. In the neighbouring alleys and along the Rue Saint-Denis hordes of ragged brats dragged cars without wheels that were filled with sand. There was worse to be seen in the Pavilion de Beurre, close by. On the side of Rue Berger, behind the inspectors' bureaux, were what were politely called the bancs of cooked meats. Every morning little closed cars, looking like boxes lined with zinc and with closed, cellar-like windows, drove up to the pavilion, having collected the leftovers of the preceding evening's feasts in the city's restaurants, embassies and ministries. Dishes of greasy meat, mangled fillets of game, the heads and tails of fish, along with cold fried vegetables were prepared in the cellars and then sold upstairs at the stands for three and five sous. Queues of small wage earners and down-and-outs —the meurts-de-faim of Paris— formed in the morning chill to sniff at the greasy plates which had the odour of an unwashed kitchen sink.

Such poverty endured. Old people remember it. Talk to some of the elderly residents sitting in the cafés and brasseries of pretty Rue Montorgueil. The pavilions were pulled down by people who wanted to say good-bye to all that and let the new generations live. That is why there is no historical heartland in Paris; the local residents had had enough of it. In its place has grown up pretty Rue Montorgueil.

ZOLA AND HIS wife died, asphyxiated by an open fireplace in their home in Médan, on the night of 28-29 September 1902. It is possible that they were murdered. In the early 1950s a businessman is said to have admitted to a journalist that he had stuffed the chimney Over the last years of his life Zola had received a number of death threats.

The Rougon-Macquart novels had become increasingly popular, and increasingly contested, too. Like his artist hero Claude Lantier, Zola had kept his distance from politics, simply painting with words the poverty he saw in the streets of Paris, in the coal mines of the north, in the flat rural landscape of the Beauce. But his story of a refugee from Devil's Island, victim of injustice, came back to haunt him in the last years of his life. He learned, in the winter of 1897-98, that a certain Captain Alfred Dreyfus had been the victim of a miscarriage of justice. A righteous fury, which he had never known before, took hold of Émile Zola; in January 1898 he published in Georges Clemenceau's Aurore his article "J'accuse." Why should a famous writer put at risk his fortune and his reputation for the sake of a Jewish officer accused of treason? "I would not have been able to live," he said.

It is remarkable how the language Zola employed to counter the anti-Semitic campaign of the anti-Dreyfusards so resembled the language of Zola in his Ventre de Paris. If there were a single ideal behind his article "J'accuse"—which would spark off the whole Dreyfus Affair—it was not one of class or of race: it was the struggle of life against the forces of death. It was the ideal Florent realized when out in rural Nanterre. "Death to the Jews! Death to Dreyfus! Death to Zola!" cried the dockers at Nantes, the workers of Rennes and of Marseille; effigies of Zola were hanged in Moulins, Montpellier, Marmande and Angoulême. "France saved from death by education," scribbled Zola on a piece of paper a few days before he died.